Significance

Millions of people suffer of gastrointestinal (GI) motility disorders. P2Y1 purine receptors and Ca2+-activated small-conductance K+ (SK) channels are established as key mediators of enteric inhibitory neurotransmission in the distal GI tract. However, the identity of the purinergic neurotransmitter in the bowel is controversial. We describe uridine adenosine tetraphosphate (Up4A) as a highly potent native activator of purinergic P2Y1 receptors and SK channels that is released spontaneously and during nerve stimulation in the human and mouse colons. We characterized potential sites of release, mimicry of the endogenous neurotransmitter, action on postjunctional targets, and metabolic pathways for Up4A. Our data identify Up4A as a novel factor in the purinergic signaling in the gut, including enteric inhibitory motor neurotransmission.

Keywords: purinergic signaling, Up4A, P2Y1 receptor, intestine, enteric nervous system

Abstract

Enteric purinergic motor neurotransmission, acting through P2Y1 receptors (P2Y1R), mediates inhibitory neural control of the intestines. Recent studies have shown that NAD+ and ADP ribose better meet criteria for enteric inhibitory neurotransmitters in colon than ATP or ADP. Here we report that human and murine colon muscles also release uridine adenosine tetraphosphate (Up4A) spontaneously and upon stimulation of enteric neurons. Release of Up4A was reduced by tetrodotoxin, suggesting that at least a portion of Up4A is of neural origin. Up4A caused relaxation (human and murine colons) and hyperpolarization (murine colon) that was blocked by the P2Y1R antagonist, MRS 2500, and by apamin, an inhibitor of Ca2+-activated small-conductance K+ (SK) channels. Up4A responses were greatly reduced or absent in colons of P2ry1−/− mice. Up4A induced P2Y1R–SK-channel–mediated hyperpolarization in isolated PDGFRα+ cells, which are postjunctional targets for purinergic neurotransmission. Up4A caused MRS 2500-sensitive Ca2+ transients in human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells expressing human P2Y1R. Up4A was more potent than ATP, ADP, NAD+, or ADP ribose in colonic muscles. In murine distal colon Up4A elicited transient P2Y1R-mediated relaxation followed by a suramin-sensitive contraction. HPLC analysis of Up4A degradation suggests that exogenous Up4A first forms UMP and ATP in the human colon and UDP and ADP in the murine colon. Adenosine then is generated by extracellular catabolism of ATP and ADP. However, the relaxation and hyperpolarization responses to Up4A are not mediated by its metabolites. This study shows that Up4A is a potent native agonist for P2Y1R and SK-channel activation in human and mouse colon.

Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate (Up4A) is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first dinucleotide isolated from living organisms that contains both purine and pyrimidine moieties. Up4A is a recently-identified, nonpeptide, endothelium-derived vasoconstrictor (1, 2). Up4A is likely associated with blood pressure regulation, because its levels in plasma are elevated in hypertensive subjects (3) and it causes vasoconstriction in deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats (4) and type 2 diabetic rats (5). Up4A also contracts rat and human airways (6) and rat gastric smooth muscles (7). Pharmacological studies suggest that Up4A causes vasoconstriction via activation of P2X1, P2Y2, and P2Y4 receptors (1) and endothelium-dependent vasodilatation via activation of P2Y1 and P2Y2 receptors (8). In porcine coronary artery Up4A causes vasodilatation via adenosine (P1) receptors (9). Furthermore, Up4A causes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration (10), stimulates monocyte and lymphocyte oxidative burst activities (11), is a potent proinflammatory agent in the vascular wall (12), and may contribute to the proinflammatory status in patients with chronic kidney disease (11). Plasma of healthy human subjects contains ∼50 nmol/L Up4A, which is sufficient to elicit vascular effects (1). The role of Up4A in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is unknown.

Enteric neural regulation of GI motility includes motor neurotransmission mediated by inhibitory neurons releasing purines that act via P2Y1 receptors (P2Y1Rs) (13–17) and apamin-sensitive small-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (SK) channels (13, 14, 18, 19). ATP (20), NAD+ (14, 15, 21), and adenosine 5′-diphosphate ribose (ADPR) (17) activate P2Y1R and SK channels and might be inhibitory neurotransmitters in the colon (22). Because Up4A appears to stimulate P2Y1Rs in endothelium, and P2Y1Rs are important for purinergic signaling in the colon, we investigated whether Up4A is released in colonic muscle, whether Up4A affects membrane potentials and contractions of colonic muscles, whether Up4A is an agonist for P2Y1R, whether cells expressing PDGF receptor α (PDGFRα) are targets of Up4A, and how Up4A is metabolized in colons of humans and mice.

Results

Up4A Is Released Spontaneously and upon Nerve Stimulation in Human and Murine Colon Muscles.

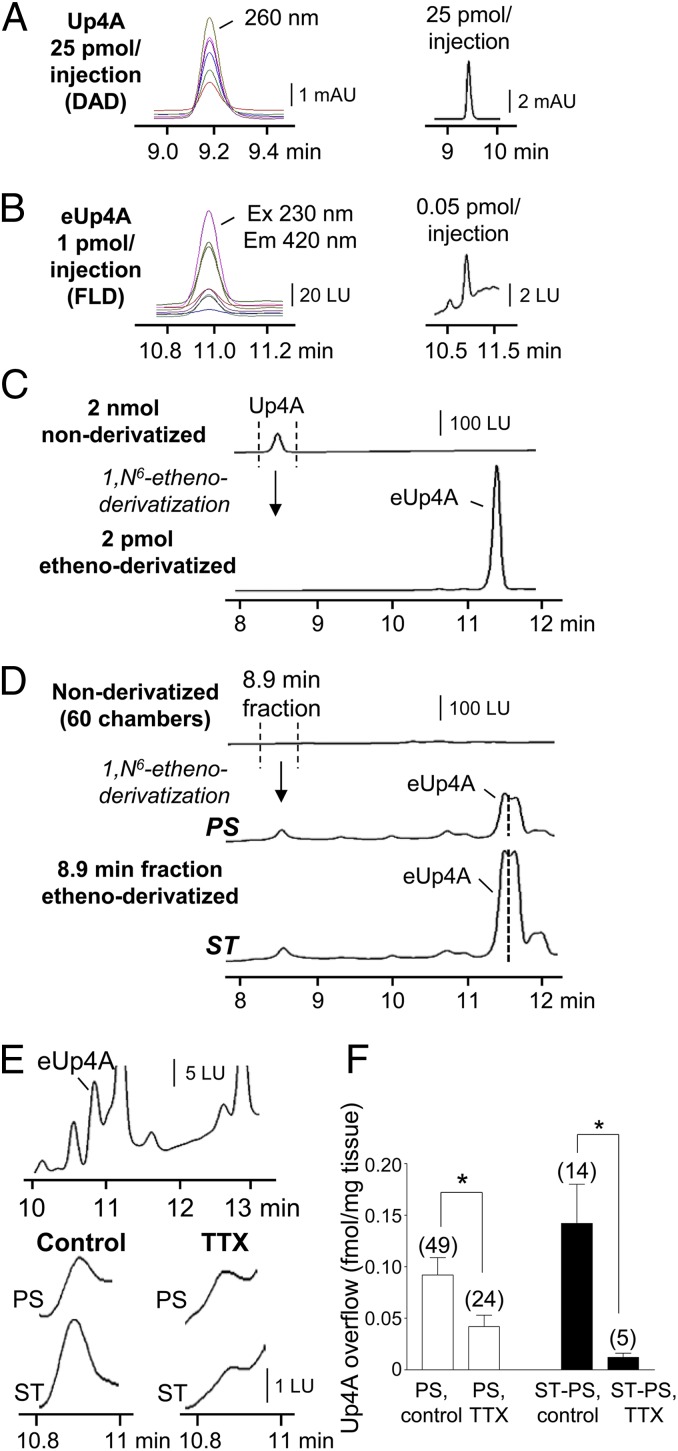

An assay using HPLC coupled with fluorescence detection (HPLC-FLD) was established to identify and quantify Up4A release from colon muscles (Fig. 1). Up4A was detected by HPLC coupled with a diode array detector (HPLC-DAD; optimum absorbance at 260 nm) with a detection limit in the picomolar range (Fig. 1A), but this sensitivity did not detect Up4A in tissue superfusates. As we had done previously to detect purines (14, 23), we processed Up4A through 1,N6-etheno derivatization and detected 1,N6-etheno-Up4A (eUp4A) with HPLC-FLD at low femtomolar concentrations (Fig. 1 B and C). Etheno derivatization of tissue superfusates revealed the presence of eUp4A at 11.2 min (Fig. 1 D and E), and HPLC fraction analysis validated that the 11.2-min chromatography peak in tissue superfusates was caused by eUp4A formed from released Up4A (Fig. 1 C and D). Therefore, etheno derivatization of tissue superfusates was used to quantify Up4A released from human and murine colon. Forty-nine colon muscle preparations from 13 patients showed an average spontaneous overflow of Up4A of 0.097 ± 0.015 fmol/mg tissue; this figure includes no detectable Up4A in 27% (n = 13) of preparations and 0.126 ± 0.02 fmol/mg Up4A in the remaining 73% of preparations (n = 36). Electrical field stimulation (EFS) evoked additional release of Up4A in ∼30% (n = 14) of preparations. Tissue superfusion with 500 μM (±)-exo-2-(6-Chloro-3-pyridinyl)-7-azabicyclo[2.2.1.]heptane (epibatidine), 500 μM 1-(6-Chloro-2-pyridinyl)-4-piperidinamine hydrochloride (SR 57227), 10 μM norepinephrine, 1 μM endothelin-1, 10 μM carbachol, 10 μM A23187, or 10 μM guanethidine (n = 3 for each) evoked no additional overflow of Up4A (SI Results). In the group that demonstrated EFS-evoked release of Up4A, the overflow of Up4A was 0.112 ± 0.03 fmol/mg before stimulation and 0.268 ± 0.05 fmol/mg during stimulation (P < 0.05, n = 14). The stimulus-induced release of Up4A (determined by subtracting the basal release from the stimulated release) was 0.157 ± 0.03 fmol/mg (n = 14) in controls and 0.012 ± 0.004 (n = 5) fmol/mg tissue in the presence of TTX (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1 E and F). The basal release of Up4A in the presence of TTX was reduced to 0.042 ± 0.011 fmol/mg (n = 24; P < 0.05 vs. controls). In murine colon tissue superfusates, the Up4A level was 0.058 ± 0.029 fmol/mg at rest and 0.285 ± 0.136 fmol/mg during EFS (16 Hz, 0.5 ms, 30 s), and the stimulated overflow was 0.228 ± 0.128 fmol/mg (n = 8, P > 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Up4A is released in human colon tunica muscularis. (A) HPLC-DAD analysis at 200- to 270-nm absorbance wavelengths identified Up4A with a lower detection limit of 25 pmol per injection. Each absorbance wavelength tested is represented by a different color chromatogram; optimum Up4A detection is at 260 nm absorbance. mAU, milli-absorbance units. (B) Up4A, etheno-derivatized with 2-chloroacetaldehyde (80 °C, 40 min), formed eUp4A that was identified with HPLC-FLD excitation (Ex) at 200–270 nm and emission (Em) at 400–470 nm. Each wavelength tested is represented by a different color chromatogram; optimum: Ex, 230 nm, and Em, 420 nm, with a lower detection limit of 0.05 pmol per injection. LU, luminescence units. (C) HPLC-FLD analysis demonstrated that the detection sensitivity of eUp4A (optimum: Ex 230 nm, Em 420 nm) was more than six orders of magnitude higher than that of Up4A (optimum: Ex 260 nm, Em 400 nm). (D) The 8.9-min fraction (presumably containing Up4A) of tissue superfusates (60 chambers combined) collected before (prestimulation, PS) and during EFS (ST, 16 Hz, 0.3–0.5 ms, for 30 s) and etheno-derivatized verified basal and EFS-evoked release of Up4A in human colon. The segment of the peak at the left of the dotted line was identified as eUp4A, because this segment coaligned precisely with the eUp4A standards. (E, Top) Segments of original chromatograms showing eUp4A in tissue superfusates. (Middle and Bottom) Basal (PS, Middle) and EFS-evoked (ST, 16 Hz, 0.3 ms, for 30 s; Bottom) overflow of Up4A (Control) was reduced by 0.5 μM TTX. (F) Averaged data (means ± SEM) for basal overflow (fmol/mg tissue) (PS) in the absence (control) and presence of 0.5 μM TTX. Stimulus-induced release of Up4A is shown as stimulated release minus basal release, ST − PS. *P < 0.05 vs. no-TTX controls; the number of experiments is shown in parentheses. Note that TTX inhibited ∼50% of the basal Up4A overflow and about 90% of the stimulation-evoked overflow of Up4A.

Up4A Causes Relaxation in Human Colon That Is Mediated by Activation of P2Y1R and SK Channels.

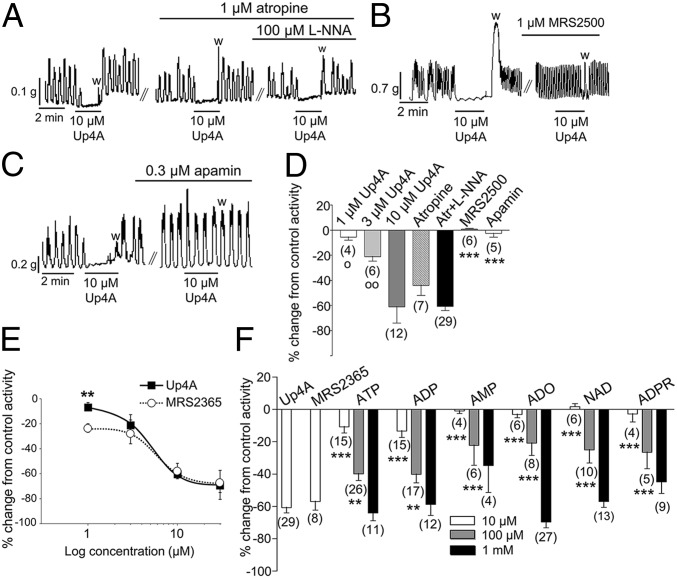

Exposure of muscles to Up4A for 2 min caused concentration-dependent relaxation of human colon (Fig. 2A). Relaxation in response to Up4A was not altered by atropine or by atropine and NG-nitro-l-arginine (l-NNA, Fig. 2A), suggesting that it did not depend on the release of acetylcholine or nitric oxide. The relaxation responses to 2-min Up4A exposure were blocked by (1R*,2S*)-4-[2-Iodo-6-(methylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-(phosphonooxy)bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-1-methanol dihydrogen phosphate ester (MRS 2500) or apamin, indicating that the responses were mediated by P2Y1R and apamin-sensitive SK channels (Fig. 2 B–D). Relaxation in response to Up4A was similar to the responses elicited by the synthetic selective P2Y1R agonist [[(1R,2R,3S,4R,5S)-4-[6-Amino-2-(methylthio)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2,3-dihydroxybicyclo[3.1.0]hex-1-yl]methyl] diphosphoric acid mono ester (MRS 2365) (Fig. 2E). Combined application of Up4A and MRS 2365 (10 µM or 30 µM) did not result in additional inhibition of spontaneous contractions (SI Results). The 2-min exposure to Up4A was more potent in inducing relaxation than 10–100 μM ATP, ADP, AMP, adenosine (ADO), NAD+, or ADPR (Fig. 2F). Note that ATP or ADP concentrations two orders of magnitude higher (i.e., 1 mM) were required to produce relaxations equivalent to the response to 10 μM Up4A. Likewise, the relaxation responses to 15- and 30-s exposure to 10 μM Up4A were more potent than the relaxation responses to 15- and 30-s exposure to 10 μM ATP, ADP, AMP, ADO, NAD+, or ADPR (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Up4A causes a P2Y1R- and SK-channel–mediated relaxation in human colon muscularis that is more potent than the relaxation in response to numerous adenine nucleotides and adenosine. (A) Inhibition of spontaneous colonic contractions by 2-min exposure (black lines) to Up4A in the absence and presence of atropine and l-NNA; w, washout. (B and C) Inhibition of spontaneous colonic contractions by Up4A (black lines) was abolished by the selective and specific antagonist of P2Y1R MRS 2500 (B) and by apamin (C). (D) Summary (means ± SEM) of concentration-dependent inhibition of spontaneous colonic contractions by Up4A (1–10 μM for 2 min) and responses to 10 μM Up4A in the presence of 1 μM atropine, atropine plus 100 μM l-NNA, 1 μM MRS 2500, and 0.3 μM apamin. Open circles denote significant differences from effects of 10 μM Up4A: oP < 0.05, ooP < 0.01. Asterisks denote a significant difference from the effect of Up4A in the presence of atropine plus l-NNA: ***P < 0.001. The number of experiments is given in parentheses. (E) Concentration-dependent inhibition of spontaneous colonic contractions by Up4A (closed squares) and the selective and specific P2Y1R agonist MRS 2365 (open circles), each at 1–30 μM. Data are presented as means ± SEM. Asterisks denote a significant difference between the effects of the two substances, each at 1 μM: **P < 0.01. n = 3–6. Note that at 3–30 μM the two substances are equally effective. (F) Summary (means ± SEM) of the inhibition of spontaneous colonic contractility by 10 μM Up4A, 10 μM MRS 2365, and 10–1,000 μM of ATP, ADP, AMP, ADO, NAD+, and ADPR. Asterisks denote significant differences from 10 μM Up4A: **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The number of experiments is given in parentheses.

Up4A Causes P2Y1R- and SK-Channel–Mediated Relaxation in Murine Proximal Colon and a Biphasic P2 Receptor-Mediated Response in Murine Distal Colon.

Exposure to Up4A (10 μM, 2 min) also caused relaxation in murine proximal colon mediated by P2Y1R and SK channels. These responses (i) were not affected by atropine (P > 0.05, n = 4) or atropine and l-NNA (P > 0.05, n = 8); (ii) were abolished by 1 μM MRS 2500 (P < 0.001, n = 7) and 0.3 μM apamin (P < 0.001, n = 3); and (iii) were absent in colons of purinergic receptor P2Y1 knockout, (P2ry1−/−) mice (P < 0.001, n = 7) (Fig. S2). In wild-type proximal colon the responses to 10 μM Up4A were similar to the responses to 10 μM MRS 2365 (P > 0.05, n = 4); however, responses to 1 μM and 3 μM Up4A were less potent than responses to equal concentrations of MRS 2365 (n = 4, P < 0.001 for both concentrations) (Fig. S2). As with human colon, 10 μM Up4A in the mouse colon was more potent than 10 μM ATP, ADP, AMP and ADO and 100 μM AMP and ADO (P < 0.001, n = 8) (Fig. S2). The relaxation in response to Up4A was identical in wild-type and in Cd73−/− mice (P > 0.05, n = 3) (SI Results), indicating that it was not mediated by the metabolism of Up4A to ADO.

In distal colon Up4A caused relaxation followed by contraction (Fig. S3). The relaxation phase was abolished by MRS 2500 (1 μM; P < 0.001, n = 11) and apamin (0.3 μM; P < 0.001, n = 3) and was absent in colons from P2ry1−/− mice (P < 0.001, n = 10). The contraction in response to Up4A (n = 12) was not affected by atropine (P > 0.05, n = 9), atropine plus l-NNA (P > 0.05, n = 30), or the P2Y6 receptor (P2Y6R) antagonist N,N″-1,4-Butanediylbis[N′-(3-isothiocyanatophenyl)thiourea (MRS 2578) (P > 0.05, n = 4) but was reduced by the nonselective P2 receptor antagonists suramin (P < 0.001, n = 7) and pyridoxalphosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS) (P < 0.01, n = 5). In distal colon from P2ry1−/− mice Up4A caused contraction that was abolished by suramin (P < 0.05, n = 5) and PPADS (P < 0.05, n = 6) but that was not affected by the P2X1 receptor antagonist 8,8′-[carbonylbis(imino-3,1-phenylene-carbonyl-imino)]bis-1,3,5-naphthalene-trisulfonic acid (NF 023) (P > 0.05, n = 6) (Fig. S3).

Up4A contains a uridine moiety, so we tested whether potential metabolites UTP, UDP, or UMP cause contraction of the distal colon (Fig. S3). At 10 μM UTP and UDP, but not UMP, caused contraction in distal colon. The contractions in response to UTP and Up4A were similar (P > 0.05, n = 7), but the contraction in response to UDP was smaller than that in response to Up4A (P < 0.01, n = 7). The selective agonist of P2Y6R 5-Iodoridine-5′-O-diphosphate trisodium salt (MRS 2693, 10 μM) caused no contraction in colons from wild-type or P2ry1−/− mice (P < 0.05, n = 3 for each mouse strain).

Up4A Induces Hyperpolarizations of Murine Colonic Muscle and PDGFRα+ Cells.

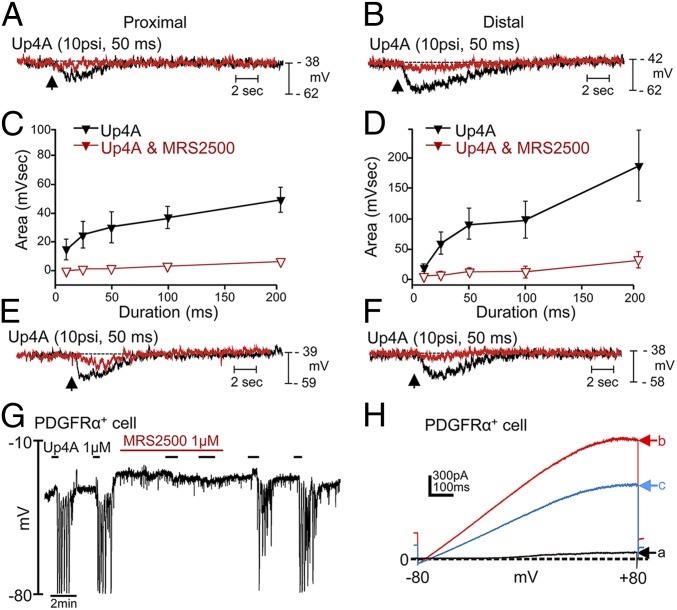

We also investigated electrophysiological responses to Up4A to determine if membrane effects might explain the contractile responses we noted. Localized pressure ejection (picospritzing) of Up4A caused transient, concentration-dependent (spritz pulses of 10- to 200-ms duration) hyperpolarization responses in murine circular muscles that were greatly reduced by MRS 2500, apamin, and the SK channel antagonist 6,12,19,20,25,26-Hexahydro-5,27:13,18:21,24-trietheno-11,7-metheno-7H-dibenzo [b,n] [1,5,12,16]tetraazacyclotricosine-5,13-diium dibromide (UCL 1684) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Electrophysiological responses to Up4A in murine circular muscle and isolated PDGFRα+ cells. (A and B) Responses to pressure ejection (spritzes) of Up4A at impalement sites in circular muscle sheets of murine proximal (A) and distal (B) colon before (black traces) and after (red traces) MRS 2500. (C and D) Summarized data in which the spritz pulses were varied from 10–200 ms (n = 6 for proximal and distal colon). (E and F) Hyperpolarization responses to Up4A (black traces) were inhibited by 0.3 μM apamin (red trace in E; 71 ± 5.8% inhibition, n = 3, P = 0.012) and 1 μM UCL 1684 (red trace in F; 68 ± 4.1% inhibition, n = 4, P = 0.00003). (G) Hyperpolarization responses under current-clamp conditions elicited by Up4A in an isolated PDGFRα+ cell (n = 5). Responses reached EK, suggesting activation of a K+ conductance, and were blocked by MRS 2500, suggesting hyperpolarization was mediated by P2Y1R. (H) Responses to ramp potentials (−80 to +80 mV) applied under voltage-clamp conditions before (black trace, a) and after (red trace, b) Up4A. Reversal potential of current activated by Up4A shifted toward EK. Outward current was reduced by 1 μM UCL 1684 (blue trace, c).

Patch-clamp experiments were performed on PDGFRα+ cells isolated from murine colon. These cells are electrically coupled to smooth muscle cells in GI muscles and were shown previously to be the cell targets for purine neurotransmitters (24). In current-clamp (I = 0) conditions, Up4A caused rapid hyperpolarization of PDGFRα+ cells that reached a peak of about −80 mV (EK in these cells). Hyperpolarization responses were inhibited by MRS 2500 (Fig. 3). In voltage-clamp conditions cells were held at −50 mV, and Up4A application elicited outward currents, with an average current density of 78.04 ± 15.95 pA/pF (n = 12) (Fig. 3). Ramp potentials revealed that the currents elicited by Up4A were caused by K+ conductance because reversal potentials shifted toward EK. Currents activated by Up4A were reduced by the SK-channel blocker UCL 1684.

Responses of 1321N1 Astrocytoma Cells Expressing the Human P2Y1R (hP2Y1-1321N1) to Up4A.

The P2Y1R agonist MRS 2365 (0.1 μM) induced Ca2+ transients in hP2Y1-1321N1 cells that were inhibited by 1 μM MRS 2500 (P < 0.0001, paired t test, n = 8) (Fig. S4D). Up4A (10 μM) also elicited Ca2+ transients in hP2Y1-1321N1 cells that were inhibited by MRS 2500 (P < 0.0003, paired t test, n = 8) (Fig. S4H). The effects of both MRS 2365 and Up4A recovered with washout of MRS 2500. Even 10 nM Up4A elicited Ca2+ transients, suggesting that physiological concentrations of Up4A likely activate the P2Y1R (SI Results).

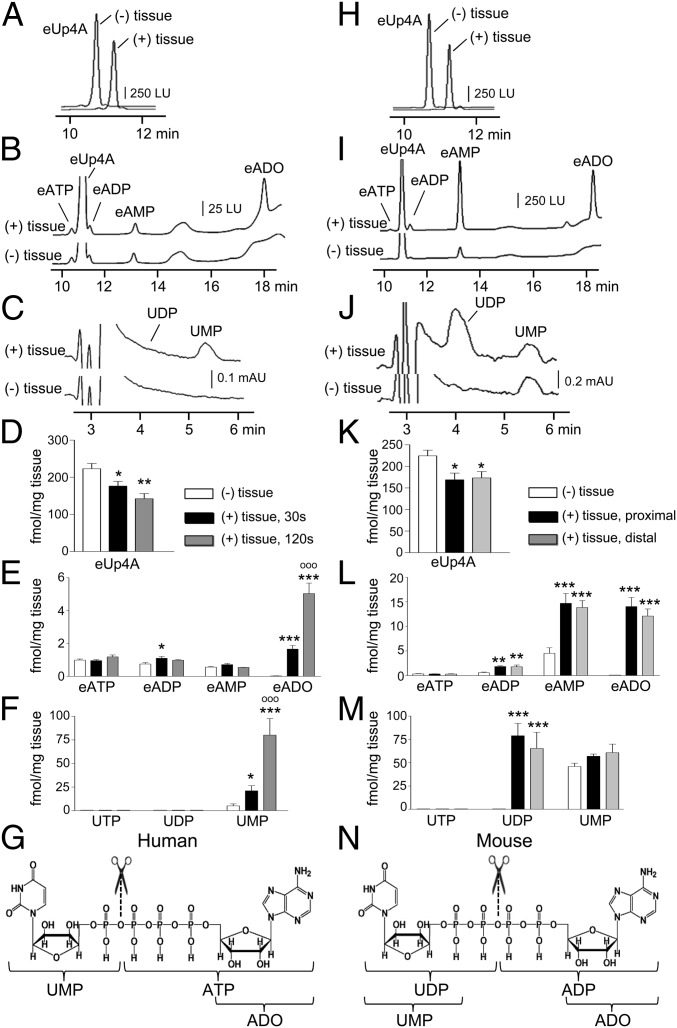

Up4A Forms UMP and ATP in Human Colon but Forms UDP and ADP in Murine Colon.

The catabolic pathways for extracellular Up4A in colonic muscles are unknown. The presence of uridine and adenine moieties in Up4A suggests that metabolites might include ATP, ADP, AMP, ADO, UTP, UDP, and UMP. We superfused colonic muscles with eUp4A (for 30 s and 120 s to match overflow and mechanical studies, respectively) and monitored the formation of etheno-ATP (eATP), etheno-ADP (eADP), etheno-AMP (eAMP), and etheno-ADO (eADO) using HPLC-FLD and UTP, UDP and UMP using HPLC-DAD. eUp4A was used as a substrate to eliminate interference of the assay with endogenous purines and to increase detection sensitivity. In the absence of tissue, eUp4A solutions contained negligible amounts of eATP, eADP, and eAMP; eADO, UTP, UDP, and UMP were not detected (Fig. 4 A–F). Superfusion of human colonic muscles with eUp4A for 30 s produced eADO and UMP but no eATP, eADP, eAMP, UTP, or UDP. Greater amounts of the same products were detected after 120-s contact. Superfusion of mouse proximal and distal colonic muscles with eUp4A for 30 s led to the formation of eADP, eAMP, eADO, UDP, and negligible amounts of UMP; eATP and UTP were not detected (Fig. 4 H–M). No significant difference was noted in the amounts of metabolites produced by superfusion of proximal or distal colon. Higher amounts of same products were detected after 120-s superfusion with eUp4A. In colons isolated from Cd73−/− mice, superfusion with eUp4A resulted in the accumulation of eAMP and reduced eADO in comparison with wild-type colon muscles (SI Results), suggesting that CD73 is the primary enzyme for ADO formation from Up4A in the colon.

Fig. 4.

Up4A forms UMP and ATP in the human colon (A–G) and UDP and ADP in the murine colon (H–N). (A and H) Excerpts of chromatograms obtained with HPLC-FLD of eUp4A (50 nM) in the absence of tissue [(−) tissue] and after 30-s contact with tissue [(+) tissue] in human (A) or murine (H) colonic muscle preparations, demonstrating a decrease in Up4A concentration after 30-s contact with tissue. LU, luminescence units. (B and I) HPLC-FLD chromatograms of etheno-purines in tissue superfusates in the absence of tissue [(−) tissue] and after 30-s contact with tissue [(+) tissue] of human (B) and murine (I) colons. eADO is observed only after the tissue was exposed to Up4A. (C and J) HPLC-DAD chromatograms showing the formation of UMP, but not UDP, in human colon (C) and the formation of UDP, but not UMP, in murine colon (J) exposed to eUp4A substrate (50 nM). mAU, milli-absorbance units. (D and K) Summary (means ± SEM) of Up4A (50 nM) degradation after contact with human colon (D) for 30 s (black bars) or 120 s (gray bars) or after 30-s contact with murine proximal (black bars) or distal (gray bars) colon (K). Asterisks denote significant differences from control [(−) tissue]: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n = 8 (30 s); n = 4 (120 s); n = 4 (mouse proximal and distal colon). (E and L) Summary (means ± SEM) of detected eATP, eADP, eAMP, and eADO in the eUp4A substrate solution in the absence of tissue (white bars) and after 30-s (black bars) or 120-s (gray bars) exposure of human colon to Up4A (E) or after 30-s exposure of murine proximal (black bars) and distal (gray bars) colon to Up4A (L). Asterisks denote significant differences from control [(−) tissue]: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n = 8 (30 s); n = 4 (120 s); n = 4 (murine proximal and distal colon). oooP < 0.001 vs. 30-s exposure to eUp4A in human colon. (F and M) Summary (means ± SEM) of detection of UTP, UDP, and UMP in the eUp4A substrate solution in the absence of tissue (white bars) and after 30-s (black bars) or 120-s (gray bars) exposure of human colon to Up4A (F) or after 30-s exposure of murine proximal (black bars) and distal (gray bars) colon to Up4A (M). Asterisks denote significant differences from control [(−) tissue]: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Open circles denote significant differences from 30-s contact of tissue with eUp4A. oooP < 0.001; n = 8 (30 s); n = 4 (120 s); n = 4 (mouse proximal and distal colon). (G and N) Chemical structure of Up4A and proposed sites of cleavage (scissors sign) and primary products in human (G) and murine (N) colonic muscles. Based on data demonstrated in A–F, we propose that in human colonic muscles Up4A forms ATP and UMP. ATP is rapidly and sequentially degraded to ADP, AMP, and ADO, so that the end detectable products are ADO and UMP. From data demonstrated in H–M we propose that in the murine colon Up4A first forms ADP and UDP. ADP is rapidly and sequentially degraded to AMP and ADO. The detectable end products are ADP, AMP, ADO, and UDP.

Discussion

We found that Up4A is released constitutively and upon nerve stimulation in human and mouse colons. Up4A is a potent inhibitor of colonic muscle contractions, and its effects are mediated by P2Y1R and activation of SK channels. Contractile effects were mirrored by hyperpolarization responses in intact muscles and in isolated PDGFRα+ cells, and P2Y1R and SK-channel blockers inhibited these effects. Previous studies have shown that P2Y1R and SK channels mediate the purinergic component of enteric inhibitory neurotransmission (13–16), and our data suggest that Up4A is likely a novel contributor to purinergic regulation in the large intestine.

Enteric nerves appear to be a source for Up4A because its overflow was reduced by about 50% by TTX. Therefore, Up4A might participate in tonic purinergic inhibition of colon excitability (25). Unlike the observations in a previous study documenting the release of NAD+ (21), stimulation of receptors present in myenteric ganglia caused no detectable release of Up4A. Sympathetic nerves and noradrenergic pathways were not likely to be involved in the release of Up4A in the colon, because neither norepinephrine nor guanethidine changed the spontaneous overflow of Up4A. The remaining basal release of Up4A might originate from nonneural sources such as vascular endothelium or another cell type. The identification of the cellular sources of Up4A in a complex tissue composed of multiple cell types may not be possible with current methodologies. Up4A is released from cultured endothelial cells by sheer stress and, to a lesser degree, by stimulation with ATP, UTP, acetylcholine, endothelin-1, and A23187 (1). Exogenous ATP and UTP could not be tested in our experiments because of interference with HPLC measurements; carbachol, endothelin-1, and A23187 failed to enhance the release of Up4A, perhaps because effective concentrations of substance did not reach endothelial cells in intramuscular blood vessels, as occurs in cultured cell lines (1), or because the amounts of Up4A released by these stimuli were below detection limits.

Despite its proposed activation of a variety of purinergic receptors (1, 8, 9), Up4A showed remarkable potency for P2Y1R in the colon: (i) The relaxation response to Up4A was abolished by the selective P2Y1R antagonist MRS 2500 and was absent in colon muscles of P2ry1−/− mice. (ii) In the human colon Up4A showed potency similar to that of the highly specific P2Y1R agonist MRS 2365. (iii) Up4A elicited dose-dependent MRS 2500-sensitive membrane hyperpolarization in the murine colon. (iv) Up4A caused MRS 2500-sensitive hyperpolarization of isolated PDGFRα+ cells that are innervated in situ and are enriched in P2ry1 and Kcnn3 (24, 26). Furthermore, hP2Y1-1321N1 cells expressing hP2Y1R responded to Up4A as they did to MRS 2365 and induced Ca2+ transients that were inhibited by MRS 2500. Finally, as is consistent with the notion that the smooth muscle relaxation is mediated by P2Y1R and is coupled to the activation of SK channels (13–15), we found that the relaxation response to Up4A in the colon, hyperpolarization responses in intact muscles, and outward currents activated in PDGFRα+ cells were inhibited by SK-channel blockers. Up4A was more potent in inducing relaxation of colonic muscles than the well-known P2Y1R agonists ADP and ATP, the recently discovered neurotransmitter candidates NAD+ and ADPR (14, 15, 17), and AMP and adenosine. The responses to even brief applications (i.e., 15–30 s) of Up4A were greater than the responses to equal concentrations of ATP and ADP, suggesting that the weaker effect of ATP and ADP cannot be attributed to ATP and ADP degradation to inactive (or less active) metabolites. Therefore, Up4A appears to be a potent, naturally occurring P2Y1R agonist in murine and human colon.

Differences noted in the mechanical responses in human and murine proximal colons (relaxation only) and murine distal colon (relaxation and contraction) may be caused by a different complement of postjunctional receptors in these muscles. Adenine compounds caused only relaxation in the proximal colon, but contractions in response to Up4A in the murine distal colon may have been mediated by P2Y2, P2Y4, or P2Y6R, which are targets for uridine-containing nucleotides (27). P2Y6R did not seem to be involved in this response, because a P2Y6R-selective agonist caused no contraction in mouse colon, and a P2Y6R-selective antagonist failed to inhibit the Up4A-induced contraction. Moreover, UTP caused more potent contractions than UDP, suggesting that P2Y2 and/or P2Y4 receptors may be involved in these responses. This suggestion could not be tested reliably, however, because P2Y2 receptor- and P2Y4 receptor-specific antagonists are unavailable. Nevertheless, suramin and PPADS inhibited the Up4A-induced contractions, suggesting that these responses are mediated by P2 receptors.

Different catabolic pathways appear to be involved in the degradation of Up4A in human and murine colons. In human colon Up4A produced ADO and UMP, suggesting the primary cleavage of Up4A was to ATP and UMP and that ATP then degraded to ADP-AMP-ADO. Although ADO caused relaxation of human colon, it did not appear to contribute to the relaxation caused by Up4A, because ADO was less potent in causing relaxation than Up4A and the response to Up4A was mediated entirely by P2Y1R and SK channels. The proposed metabolism of Up4A in human colon (Fig. 4G) is as follows (detected products are shown in bold):

In the mouse colon Up4A produced ADP, AMP, ADO, and UDP. Therefore, we propose the following degradation pathway:

In both human and murine colons some ADP was formed within the first 30 s of tissue contact. However, responses to Up4A were much greater than responses to ADP, suggesting that ADP formation cannot explain the relaxation responses to Up4A. In contrast to Up4A, the relaxation to ADP likely is mediated by receptors in addition to P2Y1R (17).

This study demonstrated the biological availability and actions of a recently-identified purine/uridine dinucleotide polyphosphate, Up4A, in human and murine colonic muscles. Up4A works via P2Y1R to activate SK channels expressed by PDGFRα+ cells and causes hyperpolarization and relaxation. Up4A is released in human colon muscle and is present in effective concentrations in human plasma (1, 3). Thus, a role for Up4A in regulating colonic motility seems likely.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Preparation.

Pdgfratm11(EGFP)Sor/J heterozygote mice (SI Materials and Methods) and wild-type siblings (C57BL/6) (3- to 6-wk old) were anesthetized by isoflurane and killed by cervical dislocation. Samples of human and mouse colon tunica muscularis were prepared by peeling away the mucosa and submucosa (14, 15). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nevada. The use of human colon tissues was approved by Human Subjects Research Committees at Renown Regional Medical Center and by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board at the University of Nevada, Reno.

Up4A Detection and Quantification.

eUp4A was produced by first acidifying 0.2 mM Up4A to pH 4.0 with citrate phosphate buffer, then adding 1 M chloroacetaldehyde, and etheno-derivatizing at 80 °C for 40 min (23). eUp4A was used as a standard to analyze Up4A in tissue superfusates. eUp4A was detected and quantified by HPLC-FLD as described below.

Up4A Overflow Experiments.

Up4A release was assessed by placing muscle strips in superfusion chambers equipped with platinum electrodes and superfusing the chambers with Krebs solution (37 °C) as described (14, 15). Superfusates were collected before and during EFS in the absence or presence of TTX, receptor agonists, guanethidine, or the calcium ionophore A23187.

HPLC Assay of 1,N6-Etheno Nucleotides and of UTP, UDP, and UMP in Tissue Superfusates.

A reverse-phased gradient liquid chromatography system equipped with a fluorescence detector was used to detect 1,N6-etheno nucleotides and nucleosides as described previously (14, 15, 17). The formation of UTP, UDP, and UMP from eUp4A was detected in the same samples using a DAD (260 nm) connected in sequence to the FLD.

Degradation of eUp4A in Mouse and Human Colons.

Catabolic products of Up4A were assessed by superfusing colonic muscles with Krebs solution containing eUp4A (50 nM) for 30 s or 120 s. Superfusion samples were analyzed for etheno-adenine and uridine metabolites using HPLC-FLD and HPLC-DAD analysis, respectively.

HPLC Fraction Analysis.

Human colon superfusates from 60 chambers were combined, concentrated, and analyzed by HPLC-FLD. An Agilent Technologies 1200 Analytical Fraction Collector was used to collect 400-μL fractions corresponding to the retention time of nonderivatized Up4A (8.9 min). Fractions were etheno-derivatized and reanalyzed by HPLC-FLD (14, 15, 28) for eUp4A content.

Patch Clamping of PDGFRα+ Cells.

After enzymatic dispersion of muscles from Pdgfratm11(EGFP)Sor/J heterozygote mice, PDGFRα+ cells were identified by eGFP expression in cell nuclei (24). Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were performed in voltage-clamp and current-clamp modes using an Axopatch 200B amplifier with a CV-4 headstage (Axon Instruments). Data were analyzed with clampfit (pCLAMP v. 9.2; Axon Instruments).

Intracellular Ca2+ Measurements.

hP2Y1-1321N1 cells (29) were grown on coverslips, loaded with 10 μM Fluo-4-AM, and perfused with either Up4A (0.01 and 10 μM) or MRS 2365 (0.1 μM) in the absence and presence of 1 μM MRS 2500. Fluo-4 was excited at a 488-nm wavelength, and the emitted light was detected at wavelengths >510 nm.

Intracellular Microelectrode Recording of Smooth Muscle Cell Membrane Potential.

Cells in colonic muscles were impaled with microelectrodes to record transmembrane potentials (14). The recording chamber was perfused continuously with Krebs solution. Up4A (0.1 mM) was applied by picospritzer. Concentration–response studies were performed by varying the pulse duration of spritzes from 10–200 ms at 10 psi (14).

Force Displacement of Smooth Muscle Strips of Human and Murine Colons.

Isometric force displacements were measured in circular muscle strips of human or mouse colons that were placed in 10-mL organ baths. Purine receptor agonists were applied in the bath for 2 min. Mechanical responses to purine agonists were expressed as the difference in area under the trace (AUT) before and during agonist addition.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Means were compared by Student’s two-tailed, paired or unpaired t test or by one-way ANOVA for comparison of more than two groups followed by a post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (GraphPad Prism, v. 3; GraphPad Software, Inc.) or SigmaPlot (Systat Software Inc.). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

See SI Materials and Methods for detailed information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Renown Medical Center for providing human tissues, Dr. Linda Thompson for donating Cd73−/− mice, Dr. T. K. Harden for donating the hP2Y1R-1321N1 cells, and Nancy Horowitz for collecting tissue samples and maintaining cells for these studies. This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Program Project Grant P01 DK41315 and NIDDK Grant R01 DK091336.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1409078111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jankowski V, et al. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate: A novel endothelium- derived vasoconstrictive factor. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):223–227. doi: 10.1038/nm1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jankowski V, et al. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate acts as an autocrine hormone affecting glomerular filtration rate. J Mol Med (Berl) 2008;86(3):333–340. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jankowski V, et al. Increased uridine adenosine tetraphosphate concentrations in plasma of juvenile hypertensives. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(8):1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.143958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumoto T, Tostes RC, Webb RC. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced contraction is increased in renal but not pulmonary arteries from DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(2):H409–H417. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00084.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsumoto T, Watanabe S, Kawamura R, Taguchi K, Kobayashi T. Enhanced uridine adenosine tetraphosphate-induced contraction in renal artery from type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats due to activated cyclooxygenase/thromboxane receptor axis. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466(2):331–342. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gui Y, et al. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate induces contraction of airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301(5):L789–L794. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00203.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan W, et al. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate induces contraction of circular and longitudinal gastric smooth muscle by distinct signaling pathways. IUBMB Life. 2013;65(7):623–632. doi: 10.1002/iub.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tölle M, et al. Differential effects of uridine adenosine tetraphosphate on purinoceptors in the rat isolated perfused kidney. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161(3):530–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Z, et al. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate is a novel vasodilator in the coronary microcirculation which acts through purinergic P1 but not P2 receptors. Pharmacol Res. 2013;67(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiedon A, et al. Uridine adenosine tetraphosphate (Up4A) is a strong inductor of smooth muscle cell migration via activation of the P2Y2 receptor and cross-communication to the PDGF receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;417(3):1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schepers E, et al. Dinucleoside polyphosphates: Newly detected uraemic compounds with an impact on leucocyte oxidative burst. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(8):2636–2644. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuchardt M, et al. The endothelium-derived contracting factor uridine adenosine tetraphosphate induces P2Y(2)-mediated pro-inflammatory signaling by monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 formation. J Mol Med (Berl) 2011;89(8):799–810. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0750-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallego D, Hernández P, Clavé P, Jiménez M. P2Y1 receptors mediate inhibitory purinergic neuromuscular transmission in the human colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291(4):G584–G594. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00474.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutafova-Yambolieva VN, et al. Beta-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in visceral smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(41):16359–16364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705510104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang SJ, et al. β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is an enteric inhibitory neurotransmitter in human and nonhuman primate colons. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(2):608–617, e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang SJ, et al. P2Y1 purinoreceptors are fundamental to inhibitory motor control of murine colonic excitability and transit. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 8):1957–1972. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durnin L, Hwang SJ, Ward SM, Sanders KM, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN. Adenosine 5-diphosphate-ribose is a neural regulator in primate and murine large intestine along with β-NAD(+) J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 8):1921–1941. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.222414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banks BE, et al. Apamin blocks certain neurotransmitter-induced increases in potassium permeability. Nature. 1979;282(5737):415–417. doi: 10.1038/282415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa M, Furness JB, Humphreys CM. Apamin distinguishes two types of relaxation mediated by enteric nerves in the guinea-pig gastrointestinal tract. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1986;332(1):79–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00633202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burnstock G. The journey to establish purinergic signalling in the gut. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(Suppl 1):8–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durnin L, Sanders KM, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN. Differential release of β-NAD(+) and ATP upon activation of enteric motor neurons in primate and murine colons. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(3):e194–e204. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutafova-Yambolieva VN, Durnin L. The purinergic neurotransmitter revisited: A single substance or multiple players? Pharmacol Ther. 2014;144(2):162–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bobalova J, Bobal P, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN. High-performance liquid chromatographic technique for detection of a fluorescent analogue of ADP-ribose in isolated blood vessel preparations. Anal Biochem. 2002;305(2):269–276. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurahashi M, et al. A functional role for the ‘fibroblast-like cells’ in gastrointestinal smooth muscles. J Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 3):697–710. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spencer NJ, Bywater RA, Holman ME, Taylor GS. Inhibitory neurotransmission in the circular muscle layer of mouse colon. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1998;70(1-2):10–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(98)00045-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peri LE, Sanders KM, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN. Differential expression of genes related to purinergic signaling in smooth muscle cells, PDGFRα-positive cells, and interstitial cells of Cajal in the murine colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(9):e609–e620. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunschweiger A, Müller CE. P2 receptors activated by uracil nucleotides—an update. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13(3):289–312. doi: 10.2174/092986706775476052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smyth LM, Bobalova J, Mendoza MG, Lew C, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN. Release of beta-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide upon stimulation of postganglionic nerve terminals in blood vessels and urinary bladder. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):48893–48903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schachter JB, Li Q, Boyer JL, Nicholas RA, Harden TK. Second messenger cascade specificity and pharmacological selectivity of the human P2Y1-purinoceptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118(1):167–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.