Abstract

Background

Non-cardiovascular chest pain (NCCP) has a high healthcare cost, but insufficient guidelines exist for its diagnostic investigation. The objective of the present work was to identify important diagnostic indicators and their accuracy for specific and non-specific conditions underlying NCCP.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed. In May 2012, six databases were searched. Hand and bibliography searches were also conducted. Studies evaluating a diagnostic test against a reference test in patients with NCCP were included. Exclusion criteria were having <30 patients per group, and evaluating diagnostic tests for acute cardiovascular disease. Diagnostic accuracy is given in likelihood ratios (LR): very good (LR+ >10, LR- <0.1); good (LR + 5 to 10, LR- 0.1 to 0.2); fair (LR + 2 to 5, LR- 0.2 to 0.5); or poor (LR + 1 to 2, LR- 0.5 to 1). Joined meta-analysis of the diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity was performed by applying a hierarchical Bayesian model.

Results

Out of 6,316 records, 260 were reviewed in full text, and 28 were included: 20 investigating gastroesophageal reflux disorders (GERD), 3 musculoskeletal chest pain, and 5 psychiatric conditions. Study quality was good in 15 studies and moderate in 13. GERD diagnosis was more likely with typical GERD symptoms (LR + 2.70 and 2.75, LR- 0.42 and 0.78) than atypical GERD symptoms (LR + 0.49, LR- 2.71). GERD was also more likely with a positive response to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) test (LR + 5.48, 7.13, and 8.56; LR- 0.24, 0.25, and 0.28); the posterior mean sensitivity and specificity of six studies were 0.89 (95% credible interval, 0.28 to 1) and 0.88 (95% credible interval, 0.26 to 1), respectively. Panic and anxiety screening scores can identify individuals requiring further testing for anxiety or panic disorders. Clinical findings in musculoskeletal pain either had a fair to moderate LR + and a poor LR- or vice versa.

Conclusions

In patients with NCCP, thorough clinical evaluation of the patient’s history, symptoms, and clinical findings can indicate the most appropriate diagnostic tests. Treatment response to high-dose PPI treatment provides important information regarding GERD, and should be considered early. Panic and anxiety disorders are often undiagnosed and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chest pain.

Background

In the USA, 6 million patients present to emergency departments with chest pain each year, at an annual cost of $8 billion [1,2]. In emergency departments, roughly 60% to 90% of the patients presenting with chest pain have no underlying cardiovascular disease [3-6]. The proportion of patients with cardiovascular disease may be higher in specialized units (cardiology emergency departments, cardiac care units (CCUs), intensive care units (ICUs)) [7] and lower in the primary care setting [6,8-10]. Physicians generally assume that patients with non-cardiovascular chest pain (NCCP) have an excellent prognosis after ruling out serious diseases. However, patients with NCCP have a high disease burden; most patients that seek care for NCCP complain of persisting symptoms on 4-year follow-up [11]. Furthermore, compared to patients with cardiac pain, patients with non-cardiac chest pain have a similarly impaired quality of life and similar numbers of doctor visits [12].

In patients with chest pain, the diagnostic investigation focuses primarily on cardiovascular disease diagnosis and is often performed by cardiologists. Upon ruling out cardiovascular disease, only vague recommendations exist for further diagnostic investigation, often delaying diagnosis and appropriate treatment and causing uncertainty for patients [13]. Limited data are available regarding efficient diagnostic investigations for patients with NCCP. Most studies investigate gastrointestinal diseases, and extensive provocation testing has been proposed [14]. Some report that almost half of the patients with NCCP will have gastrointestinal disorders [12], while others attribute more than a third of cases to psychiatric disorders, as diagnosed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSMIV). Referred pain from the spine and the chest wall are also likely substantial contributors to NCCP. Information is scarce regarding the appropriate diagnostic tests, and their sensitivity and specificity to discriminate different non-cardiac diseases.

The present systematic review aimed to identify relevant diagnostic tests for patients with NCCP, and to summarize their positive and negative likelihood ratios for underlying disease identification.

Methods

Literature search and study selection

This review, conducted in May 2012, followed the QUADAS quality assessment checklist for diagnostic accuracy studies [15]. We searched six databases (PubMed/Medline, Biosis/Biological Abstracts (Web of Knowledge), Embase (OvidSP), INSPEC (Web of Knowledge), PsycInfo (OvidSP), and Web of Science (Web of Knowledge)) using the following search terms as medical subject headings (MeSH) and other subject headings: thoracic pain, chest pain, non-cardiac chest pain, atypical chest pain, musculoskeletal chest pain, esophageal chest, and thoracic spine pain. The findings were limited to studies investigating ‘diagnosis’, ‘sensitivity and specificity’, ‘sensitivity specificity’, or chest pain/diagnosis. We applied no limits for study setting or language; however, one potentially eligible Russian language article was excluded due to lack of language proficiency [16]. Appendix 1 depicts three detailed search strategies.

To ensure search completeness, one reviewer (MW) conducted a hand search of the last 5 years in the four journals that published most articles about patients with NCCP (Gastroenterology, Chest, Journal of the American College of Cardiology and American Journal of Cardiology). Potentially eligible references not retrieved by the systematic search in the six databases were added. Bibliographies of included studies were also searched, and potential eligible references included in the full text review.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies included non-screening studies on diagnostic accuracy published between 1992 and May 2012. Inclusion criteria were studies reporting on patients of 18 years and older, seeking care for NCCP. NCCP was defined as chest pain and cardiac or other vascular disease was ruled out (that is, cardiovascular disease, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism). Exclusion criteria included studies with <30 patients per group due to concerns about sample size [17]. This group size was arbitrarily chosen to exclude studies with the highest risk of bias, while allowing a comprehensive literature overview. Based on the nomogram proposed by Carley et al. a sample size of more than >150 patients are needed to accurately assess a diagnostic test [18]; however, with this sample size cut-off, very few studies (mainly retrospective data analyses) would have been eligible.

Study selection, data extraction, and synthesis

Two reviewers (MW and KR) independently screened 6,380 references by title and abstract. Both reviewers independently reviewed the full text of 260 studies meeting the eligibility criteria. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus or third party arbitration (JS). Researchers with specific language proficiencies reviewed non-English language references. When the same study was included in several publications without change in diagnostic measure, the most recent publication was chosen and missing information was added from previous publications.

All information regarding the diagnostic test, reference test, and considered differential diagnosis was extracted and grouped according to the disease investigated. The methods used to assess accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were also extracted.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) methodology checklist for diagnostic studies [19]. Overall bias risk and study quality was rated according to the SIGN recommendations. The ratings included high quality (++; most criteria fulfilled and if not fulfilled, the study conclusions are very unlikely to be altered), moderate quality (+; some criteria fulfilled and if not fulfilled, the study conclusions are unlikely to be altered), low quality (−; few or no criteria fulfilled, conclusions likely to be altered). Studies rated as low quality by both reviewers were excluded from further analysis.

Reference standards and test evaluation

Information about method validity, reliability, practicability and value for clinical practice of the reference and the standard test was extracted and critically assessed. When several reference standards were used, all measurements were extracted and used for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize findings across all diagnostic studies. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV, respectively), and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR + and LR-, respectively) were calculated based on a 2 × 2 table (true/false positives, true/false negatives). Pretest probabilities (prevalence) and the positive and negative post-test probability of the disease were calculated. If one field contained the value 0, 0.5 was added to each field to enable value calculation. Test diagnostic accuracy was assessed as follows [20]: very good (LR+ >10, LR- <0.1); good (LR + 5 to 10, LR- 0.1 to 0.2); fair (LR + 2 to 5, LR- 0.2 to 0.5); or poor (LR + 1 to 2, LR- 0.5 to 1).

When more than four unbiased studies were available in clinically similar populations and with comparable index and reference tests, we performed joined meta-analysis of the diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity. We used a hierarchical Bayesian model, as proposed by Rutter and Gatsonis [21], which accounts for the within-study and between-study variability and the potentially imperfect nature of the reference test. The hierarchical Bayesian model was set up as follows: we assumed J diagnostic studies in the meta-analysis, with crosstabulation between index test (T1) and reference test (T2) available for each study, and both tests assumed to be dichotomous (1 = positive test result, 0 = negative test result). Each study was assumed to use a different cut-off value (θj) to define a positive test result. The diagnostic accuracy of each study was denoted by αj. The model structure implied a within-study level for study-specific parameters (θj and αj), and a between-study level for parameters common among all studies. The model could theoretically be extended to include study-specific covariates such as percentage of female patients or mean age to reduce heterogeneity on study level.

Appendix 2 gives details of the model set up and prior distributions. The results of the Bayesian analysis are samples from the posterior distribution of the parameters, and estimates are presented as posterior means (50% quantile), and lower (2.5% quantile) and upper (97.5% quantile) bounds, resulting in a 95% credible region. Analyses were performed using R statistical software and the ‘HSROC’ package [22,23].

Ethics statement

For this study no ethical approval was required. No protocol was published or registered. All methods were determined a priori.

Results

Study selection

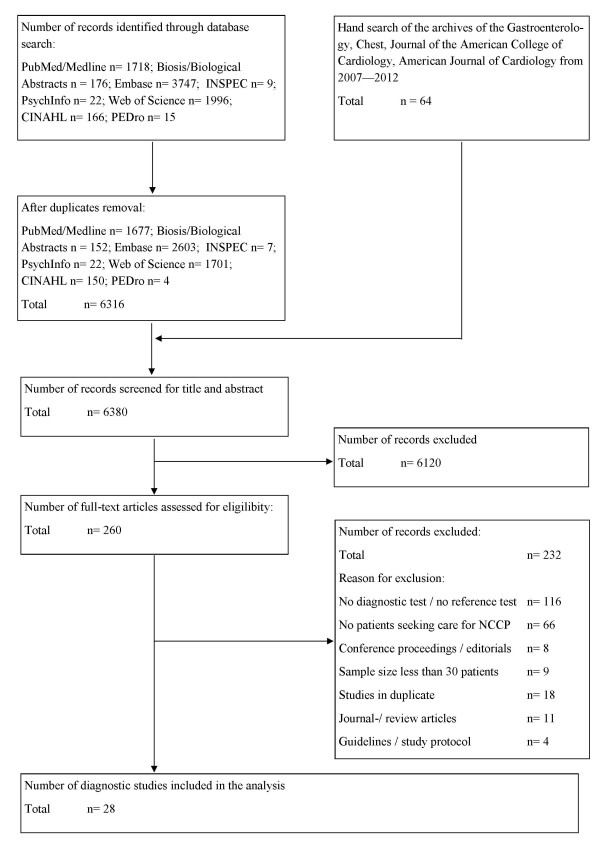

Figure 1 summarizes the search and inclusion process. Out of 6380 records, 260 were reviewed in full text, resulting in exclusion of 232 studies. In total, the analysis included 28 studies. The reasons for exclusion of the 232 studies are given in Figure 1 and overview of excluded studies reviewed in full text is give in Appendix 3.

Figure 1.

Study flow.

Study characteristics

Table 1 presents the study characteristics, and included patients. In all, 20 studies (71%) evaluated diagnostic tests to identify gastrointestinal disease, mainly gastroesophageal reflux disorders (GERD), underlying NCCP. Musculoskeletal chest pain was investigated in three studies (11%), and psychiatric conditions in five studies (18%). Study quality was good in 15 studies (54%) and moderate in 13 (46%; Appendix 4). No study had to be excluded because of poor study quality.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristic of the studies

| Author | Study design | Recruitment | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | n all (n female), subgroups | Age, mean (SD) | Disease duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms suggesting gastroesophageal reflux (GERD)-related non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP) | |||||||

| Kim et al., 2007 [24] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Inpatients with NCCP, referred by a cardiologist after negative cardiac evaluation. Tertiary care, Seoul, Korea. |

NCCP was defined when patients were admitted for chest pain to the coronary unit for ≥1 episode of unexplained chest pain/week for ≥3 months. Cardiac chest pain was ruled out by electrocardiogram (ECG), normal enzymes, negative treadmill exercise testing, normal or insignificant ECG changes after intravenous ergonovine injection in coronary angiograms. |

Severe liver, lung, renal or hematological disorders. History of peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal (GI) surgery, connective tissue disorder and chest pain originating in a musculoskeletal disorder. |

58 (female 37), NCCP with GERD symptoms (sy) 24, NCCP without GERD sy 34 |

54.6 (10.4) |

17% <6 months, 17% 6 to 12 months, 51% 1 to 5 years, 16% >5 years |

| Hong et al., 2005 [25] |

Retrospective data analysis, funding NR |

Patients with a clinical suspicion of esophageal motility abnormalities and pathological acid exposure within 1 month were included in this analysis. Tertiary care, Seoul, Korea. |

Patients with suspicion of esophageal motility abnormalities and pathological acid exposure. NCCP was defined as recurrent angina-like or substernal chest pain believed to be unrelated to the heart, after comprehensive evaluation by the cardiologist. |

Obstructive lesions, previous esophageal balloon dilatation, botulism toxin injection, or anti-reflux surgery. No complaints associated with symptoms centered on the esophagus. Connective tissue diseases. |

462 (female 269), dysphagia 53, NCCP 186, GERD sy 117 |

47.6 (10.9) |

NR |

| Netzer et al., 1999 [26] |

Retrospective data analysis, funding NR |

First-time referrals to esophageal function testing laboratory. Tertiary care, Bern, Switzerland. |

First-time referrals to esophageal function testing laboratory. NCCP group included all patients referred for GI testing because of NCCP. Additional information was obtained by contacting the general practitioner (GP) and interviews. |

NR |

303 (female 145), GERD 143, dysphagia 56, NCCP 45 |

50 (15) |

NR |

| Mousavi et al., 2007 [27] |

Prospective observational, funding NR |

Outpatient referral by cardiologist after non-invasive diagnostic evaluation and exclusion of a cardiac or other source. Semnan, Iran. |

Patients with NCCP referred to the gastrointestinal clinic. NCCP was diagnosed when chest pain was believed to be unrelated to the heart after an evaluation by a cardiologist including non-invasive testing and no apparent other diagnosis was present. |

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, peptic stricture, duodenal/gastric ulcer. History of upper GI surgery, scleroderma, diabetes mellitus, neuropathy, myopathy or functional bowel disorders, any condition that may affect lower esophageal sphincter pressure or decrease acid clearance time. |

78 (female 37), NCCP with GERD sy. 35, NCCP without GERD 43 |

50.4 (2.3) |

3 to 30 days (mean 9.3 ± 4.2 days) |

| Singh et al., 1993 [28] |

Retrospective data analysis, funding NR |

All consecutive outpatients referred to Esophageal Laboratory for evaluation of upper gastrointestinal complaints. Alabama, USA. |

61 patients had NCCP and were analyzed in comparison to reflux patients for findings in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and ambulatory 24 h pH monitoring |

NR |

153 (female 40) |

NR |

NR |

| Ho et al., 1998 [29] |

Cross-sectional, research grant, National University of Singapore |

Outpatient referral for NCCP to the gastroenterology service. Tertiary care, Singapore. |

Recurrent NCCP ≥3 months. Normal cardiac evaluation (non-obstructed coronary arteries (<50% diameter narrowing), dobutamine stress echocardiography, exercise ECG). Cardiologist evaluation not cardiac. |

No history of esophageal disorder or esophageal surgery |

61 (NR) |

NR |

≥3 months |

| Lam et al., 1992 [30] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Patients referred to the gastroenterologist after being released from a cardiac care unit (CCU) where they were admitted with suspected myocardial infarction but negative cardiac evaluation. Secondary care, Haarlem, The Netherlands. Patients were eligible for the study when a cardiologist determined the chest pain to be of non-cardiac origin. |

Episode of acute, prolonged retrosternal chest pain. Cardiac chest pain was ruled out when no abnormalities on admission ECG, negative results on heart enzyme tests, negative exercise test. Further cardiac testing (coronary angiography) was only performed when considered necessary by the cardiologist. |

Age >80 years, ECG ischemic alterations on the admission, arrhythmias, or signs of congestive heart failure |

41 (female 41) |

61.4 (range 40 to 75) |

Acute episode of chest pain |

| Studies investigating the efficacy and diagnostic value of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trials in GERD-related NCCP | |||||||

| Dickman et al., 2005 [31] |

Randomized, controlled trial (RCT), double-blind, crossover, Janssen Pharmaceutica und Eisai Inc. |

Outpatient referral by a cardiologist after negative cardiac evaluation. Tertiary care, Arizona, USA. |

NCCP ≥3 episodes/week (angina-like) for ≥3 months. Normal/insignificant findings coronary angiogram, or insufficient evidence for ischemic heart disease (IHD) in non-invasive tests. |

Severe comorbidity, previous empirical anti-reflux regimen, history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal surgery |

35 (female 12), GERD + 16 (45.7%), GERD- 19 (54.3%) |

55.6 (10.10) |

≥3 months |

| Bautista et al. 2004 [32] |

RCT, double-blind, crossover, TAP Pharmaceuticals |

Outpatient referral by a cardiologist after negative cardiac evaluation. Tertiary care, Arizona, USA. |

NCCP ≥3 episodes (angina-like) for ≥3 months. Normal/insignificant findings coronary angiogram, or insufficient evidence for IHD in non-invasive tests. |

Severe comorbidity, previous empirical anti-reflux regimen, history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal surgery |

40 (female 9), placebo 40, GERD + 18, GERD- 22 |

54.4 (2.78) |

≥3 months |

| Fass et al. 1998 [33] |

RCT, double-blind, crossover, Astra-Merck research grant |

Outpatient referral by a cardiologist after negative cardiac evaluation. Tertiary care, Arizona, USA. |

NCCP ≥3 episodes (angina-like) for ≥3 months. Normal/insignificant findings coronary angiogram, or insufficient evidence for IHD in non-invasive tests. |

Previous empirical anti-reflux regimen, history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal surgery |

37 (female 1), GERD + 23, GERD- 14 |

58.2 (2.3) |

≥3 months |

| Pandak et al., 2002 [34] |

RCT, double-blind, crossover, Astra Zeneca |

Patients presented with recurrent chest pain, whose chest pain was determined by cardiologist to be of non-cardiac origin with the aid of methoxyisobutylisonitrile (MIBI) testing. Tertiary care, Arizona, USA. |

Unexplained recurrent chest pain determined to be of non-cardiac origin by a cardiologist and had negative results on MIBI testing |

Previous empirical anti-reflux regimen, gastric or duodenal ulcer, prior gastric surgery, abnormalities on physical exam or chest x-ray that would explain the chest pain |

42 (female 24), GERD + 20, GERD- 18 |

Range 22 to 77 |

≥6 months |

| Kim et al., 2009 [35] |

Prospective observational, Janssen Pharmaceuticals |

Inpatients referred after negative cardiac examination by cardiologists to gastroenterology. Tertiary care, Seoul, Korea. |

NCCP was defined when patients were admitted for chest pain to the coronary unit for ≥1 episode of unexplained chest pain/week for ≥3 months. Cardiac chest pain was ruled out by ECG, normal enzymes, negative treadmill exercise testing, normal or insignificant ECG changes after intravenous ergonovine injection in coronary angiograms. |

Severe comorbidity, history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal surgery, history of connective tissue disorder and chest pain originating from musculoskeletal disorder |

42 (female 17), GERD + 16, GERD- 26 |

53.9 (12.8) |

≥3 months: n = 12 3 to 12 months; n = 23 1 to 5 years; n = 7 >5 years |

| Xia et al., 2003 [36] |

RCT, single blind, Simon KY Lee Gastroenterology Research Fund |

Referred by a cardiologist after negative cardiac evaluation. Tertiary care, Hong Kong, China. |

NCCP ≥12 weeks during last 12 months. Normal coronary angiograph, chest pain considered by a cardiologist to be NCCP. |

Pathologic endoscopic finding, previous anti-reflux regimen, apparent heartburn, acid reflux, dysphagia and dyspepsia |

68 (female 42), placebo 32, lansoprazole 36 |

58.2 (10.0) |

≥12 weeks |

| Kushnir et al., 2010 [37] |

Retrospective data analysis, Mentors in Medicine, Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA |

Outpatients referred for ambulatory pH monitoring for the evaluation of unexplained chest pain. Tertiary care, Missouri, USA. |

Unexplained chest pain. Cardiac causes were excluded in all instances before referral. |

Anti-reflux surgery in the past, chest pain was not the dominant symptom, pH manometry data incomplete |

98 (female 75) |

51.8 (1.1) |

7.4 ± 4.1 years |

| Lacima et al. 2003 [38] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Referred by a cardiologist after negative cardiac evaluation. Barcelona, Spain. |

Normal ECG, cardiac enzymes, treadmill exercise testing, coronary angiography and epicardial coronary arteries or with <25% narrowing, no ECG changes after intravenous ergonovine injection |

Previous anti-reflux regimen, calcium channel blockers, beta blockers and/or nitrates were withdrawn at least 7 days before the study |

120 (female 62), patients 90, volunteers 30 |

57 (27 to 82) |

NR |

| Studies investigating the value of provocation tests for the diagnosis of GERD-related NCCP | |||||||

| Cooke et al., 1994 [39] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Patients in whom coronary angiography was performed for the diagnosis of new chest pain. Secondary care, London, UK. |

New chest pain and normal coronary anatomy with exertional pain as principal complaint |

Mitral valve prolapse, left ventricular hypertrophy, previous myocardial infarction, abnormalities of resting wall motion on echocardiography, pain at rest only, unable to exercise. Previous anti-reflux regimen, previous gastroenterologist assessment. |

66 (female 34), non-cardiovascular disease (CVD) 50, CVD 16 (controls) |

53 (non-CVD), CVD 58, range 32 to 72 |

3.4 years |

| Bovero et al., 1993 [40] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Patients investigated for chest pain. Secondary care, Genova, Italy. |

Chest pain, no coronaroactive drugs for ≥5 days. No anti-reflux regimen ≥3 days. |

Chest pain of organic and/or functional cardiologic origin (evaluated by: ECG, two ergometry tests, dynamic ECG, thallium myocardial scintigraphy under physical stress or echodypiridamole test, ergonovine or methyl-ergometrine test, angiography) |

67 (female 43), pain at rest 46, exertional pain 21 |

53 (range 34 to 76) |

NR |

| Romand et al., 1999 [41] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Referred after negative cardiac evaluation. Secondary care, Lyon, France. |

Normal coronary anatomy, normal ECG, negative treadmill exercise |

Cardiologic origin of symptoms, history of upper gastrointestinal surgery, duodenal or gastric ulcer, peptic stricture or stricture by a tumor |

43 (female 19) |

56 (range 31 to 78) |

n = 25 <1 year; n = 7 1 to 5 years; n = 11 >5 years |

| Abrahao et al., 2005 [42] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Referred by a cardiologist after negative cardiac evaluation. Tertiary care, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. |

≥1 episode of NCCP/week, normal coronary angiogram or with <30% narrowing |

Chronic obstructive lung disease, asthma, cardiac arrhythmia, cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease |

40 (female 32) |

54.7 (8.4) |

Mean 24 months (range 1 to 360 months) |

| Ho et al., 1998 [29] |

Cross-sectional, research grant from the National University of Singapore |

Referred for NCCP to the gastroenterology service, Singapore |

Recurrent chest pain of ≥3 months; cardiologists evaluation normal and symptoms not cardiac (non-obstructed coronary arteries (<50% luminal narrowing), dobutamine stress echocardiography, exercise ECG) |

No history of proven esophageal disorder or esophageal surgery |

80 (female 38) |

48 (range 21 to 75) |

≥3 months |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis-related NCCP | |||||||

| Achem et al., 2011 [43] |

Retrospective data analysis, funding NR |

Referred for endoscopic evaluation of NCCP, who had esophageal biopsies for suspected eosinophilic esophagitis. Secondary care, Florida, USA. |

Chest pain suspected of being esophageal origin after negative cardiac evaluation (either by non-invasive stress testing or coronary angiography) |

Dysphagia (if this was the main reason for endoscopy). Anticoagulant use. |

171 (female 104), 24 (female 7) eosinophilia, 147 (female 97) normal histology |

59 (24 to 86) normal histology, 55 (21 to 81) eosinophilia |

NR |

| Musculoskeletal NCCP | |||||||

| Stochkendahl et al., 2012 [44] |

Cross-sectional, Foundation Chiropractic Research and Postgraduate Education, Government |

Patients discharged form an emergency cardiology department. Tertiary care, Odense, Denmark. |

Acute (<7 days) chest pain primary complaint. Pain in the thorax and/or neck. Understand Danish. Age 18 to 75 years, resident of the Funen County. |

Cardiovascular disease, previous percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft: other definite cause, inflammatory joint disease, insulin dependent diabetes, fibromyalgia, malignant disease, apoplexy, dementia or unable to cooperate, major osseous anomaly, osteoporosis, pregnancy |

302 (female 132) |

52.5 (11.0) |

Acute episode, <7 days before admission |

| Bosner et al. 2010 [45] |

Cross-sectional with 6 months follow-up, federal Ministry of Education and Research grant |

Consecutive recruitment of all patients presenting to chest pain in a GP clinic. An independent interdisciplinary reference panel decided about the etiology of chest pain. |

Age >35 years, pain (acute or chronic) localized between clavicles and lower costal margins and anterior to the posterior axillary lines |

Patients whose chest pain had been investigated already and/or who came for follow-up for previously diagnosed chest pain were excluded |

1,212 (female 678), chest wall symptom (CWS) 565 (female 330) |

All 59 (35 to 93), CWS 58 (35 to 90) |

Acute pain 28.4% |

| Manchikanti et al., 2002 [46] |

Cross-sectional, no funding |

Chronic thoracic pain, managed by one physician and undergoing diagnostic medial branch blocks. Private pain practice, USA. |

Pain for ≥6 months. Failure of conservative management with physical therapy, chiropractic management and drug therapy. Age 18 to 90 years. |

No radicular pattern of pain, no disc herniation on MRI |

46 (female 31) |

46 (2.2) |

≥6 months, mean 86 (SD 17.2) months |

| NCCP related to psychiatric diseases | |||||||

| Kuijpers et al., 2003 [47] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Discharged from the hospitals first-heart-aid service with a diagnosis of NCCP received an envelope |

Chest pain or palpitation presenting to first-heart-aid service, received no cardiac explanation |

Dementia, live ≥50 km from the hospital. Do not speak Dutch. |

344 (female 151), Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) ≥8: 266 (female 123); HADS <8: 78 (female 28) |

HADS ≥8: 55.81 (13.03); HADS <8: 60.55 (10.84) |

NR |

| Demiryoguran et al., 2006 [48] |

Cross-sectional, funding NR |

Patients admitted to the ER and discharged with a diagnosis of NCCP. Ismir, Turkey. |

Cardiac chest pain ruled out. Normal ECGs and low or stable levels of cardiac markers. |

Unstable vital signs, uncooperative and disoriented patients. Established diagnoses. Documented coronary artery disease, history of trauma to chest wall, back or abdomen within the previous week. |

157 (female 89), HADS <10: 108 (female 55), HADS >10: 49 (female 34) |

41.6 (11.7) |

NR |

| Foldes-Busque et al., 2011 [49] |

Cross-sectional, Groupe interuniversitaire de recherche sur les urgences (GIRU) and Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec |

Emergency department (ED), Monday to Friday between 8 AM and 4 PM. Tertiary care, Quebec, Canada. |

Low-risk unexplained chest pain, ≥18 years old. English or French speaking, normal serial ECG, normal cardiac enzymes. |

Explained chest pain (for example, ischemic, cause identifiable by radiography). Medical condition that could invalidate the interview (for example, psychosis, intoxication, or cognitive deficit), any unstable condition, or any trauma. |

507 (NR), derivation sample 201 (female 101); validation sample 306 (female 173) |

Derivation condition 54.2 (13.9), validation condition 53.3 (14.4) |

NR |

| Fleet et al. 1997 [50] |

Cross-sectional, Fonds de Recherché en Santé Québec |

Consecutive patients presenting to ambulatory walk in ED, patients with or without IHD, Québec, Canada |

Complaint of chest pain, understand French, able to complete evaluation in the ED |

Cognitive impairment, psychotic state |

Derivation sample 180 (female 63), validation sample 212 |

Development 57.6 (12.6), validation 56 (12.2) |

NR |

| Katerndahl et al., 1997 [51] | Cross-sectional, public health and service Establishment of Departments of Family Practice | Presented to the GP with a chief compliant of new-onset chest pain. Primary care, Texas, USA. | Adults 18 years and older, new-onset chest pain, only one complaint (chest pain) as well as those with several symptoms that included chest pain | Previous investigation for chest pain at the practice | 51 (NR) | 42.6 (14.6) | New onset |

NR not reported.

Accuracy of symptoms for the diagnosis of GERD

Table 2 summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of the diagnostic tests relevant for clinical practice. A comprehensive overview of all evaluated diagnostic tests is provided in Appendix 5. For diagnosis of GERD, the most common reference tests (endoscopy and/or 24-h pH-metry) are reported.

Table 2.

Summary of diagnostic accuracy of tests used in non-cardiac chest pain

|

Author, year |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluated test | Reference standard | Prevalence,% | LR+ | LR- | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Kim et al. [24] |

NCCP with atypical GERD symptoms |

Endoscopy (LA classification) and/or 24 h pH-metry (>4%, pH <4 |

24 |

0.49 |

2.71 |

| Kim et al. [24] |

NCCP with typical GERD symptoms |

Same |

67 |

2.75 |

0.42 |

| Mousavi et al. [27] |

NCCP with typical GERD symptoms |

GERD if two tests positive: endoscopy (Hentzel-Dent), Bernstein test, omeprazole trial |

45 |

2.70 |

0.78 |

| Mousavi et al. [27] |

NCCP relieved by antacid |

Same |

45 |

0.51 |

3.51 |

| Mousavi et al. [27] |

NCCP and heartburn in past history |

Same |

45 |

2.15 |

0.74 |

| Mousavi et al. [27] |

NCCP and regurgitation in past history |

Same |

45 |

2.98 |

0.61 |

| Hong et al. [25] |

NCCP |

Manometry (Specler 2001 criteria) and/or 24 h pH-metry (>4% pH <4) |

43 |

0.83 |

1.13 |

| Hong et al. [25] |

Control: dysphagia |

Same |

45 |

1.27 |

0.97 |

| Hong et al. [25] |

Control: GERD-typical symptoms |

Same |

44 |

1.26 |

0.93 |

| Netzer et al. [26] |

NCCP |

Manometry and/or 24 h pH-metry (>10.5% pH <4) |

84 |

0.43 |

1.23 |

| Netzer et al. [26] |

Control: GERD-typical symptoms |

Same |

84 |

1.53 |

0.74 |

| Netzer et al. [26] |

Control: dysphagia |

Same |

84 |

1.16 |

0.97 |

| Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial | |||||

| Dickman et al. [31] |

Rabeprazole 20 mg twice a day for 1 week SIS ≥50% |

Endoscopy (Hentzel-Dent grades) and/or 24 h pH-metry (>4.2% pH <4) |

46 |

7.13 |

0.28 |

| Dickman et al. [31] |

Placebo for 1 week |

Same |

46 |

0.89 |

1.03 |

| Bautista et al. [32] |

Lansoprazole 60 mg AM, 30 mg PM for 1 week SIS ≥50% |

Endoscopy (Hentzel-Dent grades) and/or 24 h pH-metry (>4.2% pH <4) |

45 |

8.56 |

0.24 |

| Bautista et al. [32] |

Lansoprazole 60 mg AM, 30 mg PM for 1 week SIS ≥65% |

Same |

45 |

18.33 |

0.17 |

| Bautista et al. [32] |

Placebo for 1 week |

Same |

45 |

0.61 |

1.22 |

| Fass et al. [33] |

Omeprazole 40 mg AM, 20 mg PM for 1 week SIS ≥50% |

Endoscopy (Hentzel-Dent grades) and/or 24 h pH-metry (>4.2% pH <4) |

62 |

5.48 |

0.25 |

| Fass et al. [33] |

Placebo for 1 week |

Same |

62 |

3.04 |

0.84 |

| Pandak et al. [34] |

Omeprazole 40 mg twice a day for 2 weeks SIS ≥50% |

Endoscopy and/or 24 h pH-metry (>4.2% pH <4) |

53 |

2.70 |

0.15 |

| Pandak et al. [34] |

Placebo for 2 weeks SIS ≥50% |

Same |

53 |

0.30 |

1.14 |

| Kim et al. [35] |

NCCP rabeprazole for 1 week SIS ≥50% |

Endoscopy (LA classification) and/or 24 h pH-metry (>4.0 pH <4) |

38 |

2.17 |

0.65 |

| Kim et al. [35] |

NCCP rabeprazole for 2 weeks SIS ≥50% |

Same |

38 |

3.02 |

0.26 |

| Xia et al. [36] |

Lansoprazole 30 mg once a day for 4 weeks SIS ≥50% |

24 h pH-metry (De Meester pH <4, 7.5 s) |

33 |

2.75 |

0.13 |

| Xia et al. [36] |

Placebo for 4 weeks SIS ≥50% |

Same |

38 |

0.95 |

1.03 |

| Kushnir et al. [37] |

High-degree response on PPI (not specified) |

24 pH-metry (≥4%, pH <4) |

53 |

1.97 |

0.38 |

| Provocation test |

|

|

|

|

|

| Cooke et al. [39] |

NCCP during exertional pH-metry |

24 h pH-metry (5.5% pH <4 for 10 s) |

38 |

14.40 |

0.79 |

| Cooke et al. [39] |

Control group: CVD with angina: exertional pH-metry |

Same |

19 |

4.33 |

0.72 |

| Bovero et al. [40] |

NCCP with normal ECG during exertional pH-metry |

24 h pH-metry (De Meester criteria: >4.5% pH <4)) |

69 |

7.76 |

0.66 |

| Bovero et al. [40] |

NCCP at rest: NCCP with normal ECG during exertional pH-metry |

Same |

74 |

3.88 |

0.74 |

| Bovero et al. [40] |

NCCP exertion/mixed: NCCP with normal ECG during exertional pH-metry |

Same |

57 |

10.00 |

0.50 |

| Romand et al. [41] |

NCCP: pH <4 for 10 s during exertional pH-metry |

24 h pH-metry (De Meester criteria: >4.5% pH <4)) |

23 |

1.65 |

0.52 |

| Abrahao et al. [42] |

NCCP reproducible during balloon distension |

Endoscopy (Savary-Miller) and/or manometry and/or pH-metry (De Meester criteria: >4.5% pH <4 |

88 |

2.00 |

0.75 |

| Abrahao et al. [42] |

NCCP reproducible during Tensilon test |

Same |

88 |

0.43 |

1.38 |

| Abrahao et al. [42] |

NCCP reproducible during Bernstein test |

Same |

88 |

1.29 |

0.93 |

| Abrahao et al. [42] |

Tensilon and Bernstein Test and balloon distension (+ if 1 test +) |

Same |

88 |

0.95 |

1.07 |

| Ho et al. [29] |

NCCP reproducible during Bernstein test |

24 h pH-metry (>4% pH <4, 4 s) |

23 |

0.75 |

1.06 |

| Musculoskeletal disorders |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

≥3 of 5 palpation findings: (1) sitting motion of end-play restriction in lateral flexion and rotation segment C4 to C7 and Th1 to Th8. (2) Prone motion joint-play restriction segment Th1 to Th8. (3) Prone evaluation paraspinal tenderness segment Th1 to Th8. (4) Supine manual palpation muscular tenderness of 14 points anterior chest wall. 5) Supine evaluation of tenderness of the costosternal junctions of costa 2 to 6 and xiphoid process |

Diagnosis using a standardized examination protocol: |

37 |

1.52 |

0.03 |

| (1) A semistructured interview: pain characteristics, lung and gastrointestinal symptoms, past medical history, height, weight, cardiovascular risk factors | |||||

| (2) A general health examination: blood pressure, pulse, heart and lung stethoscopy, abdominal palpation, neck auscultation, signs of left ventricular failure, neurological examination | |||||

| (3) Manual examination of the muscles and joints (neck, thoracic spine and thorax): active range of motion, manual palpation 14 points muscular tenderness of the anterior chest wall and segmental paraspinal muscles, motion palpation for joint-play restriction of the thoracic spine (Th1 to 8), and end play restriction of the cervical and thoracic spine | |||||

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Chest wall symptom (CWS) score: localized muscle tension, stinging pain, pain reproducible by palpation, absence of cough |

Interdisciplinary consensus: cardiologist, GP, research associate (based on reviewed baseline, follow-up data at 6 weeks and 6 months) |

47 |

1.82 |

0.20 |

| Cut-off test negative 0 to 1 points | |||||

| Bosner et al. [45] |

CWS score: localized muscle tension, stinging pain, pain reproducible by palpation, absence of cough |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

3.02 |

0.47 |

| Cut-off test negative 0 to 2 points | |||||

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Biomechanical dysfunction (part of the standardized examination protocol)a |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.58 |

0.00 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Anterior chest wall tenderness |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.39 |

0.06 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Angina pectoris (uncertain or negative) |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.26 |

0.12 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Pain worse on movement of torso |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

3.39 |

0.78 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Pain worse with movement |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

2.13 |

0.75 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Positive/possible belief in pain origin from muscle/joints |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.17 |

0.20 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Pain relief on pain medication |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

3.26 |

0.83 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Pain reproducible by palpation |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

2.08 |

0.54 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Paraspinal tenderness |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.36 |

0.48 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Localized muscle tension |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

2.41 |

0.52 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Chest pain present now |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.35 |

0.46 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Pain now |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

1.15 |

0.85 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Pain debut not during a meal |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.10 |

0.23 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Sharp pain |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.89 |

0.80 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Stinging pain |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

1.87 |

0.66 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Hard physical exercise at least once a week |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.19 |

0.91 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Pain not provoked during a meal |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

1.09 |

0.25 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Not sudden debut |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

2.90 |

0.63 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Pain >24 h |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

1.30 |

0.92 |

| Stochkendahl et al. [44] |

Age ≤49 years old |

Standardized examination protocol |

37 |

2.10 |

0.56 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Pain mostly at noon time |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

0.50 |

1.02 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Cough |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

0.28 |

1.18 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Known IHD |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

0.52 |

1.11 |

| Bosner et al. [45] |

Pain worse with breathing |

Interdisciplinary consensus |

47 |

1.28 |

0.93 |

| Psychiatric diseases |

|

|

|

|

|

| Kuijpers et al. [47] |

Anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A score, cut-off ≥8) |

Diagnosis anxiety disorders (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (gold standard)) |

58 |

2.03 |

0.03 |

| Demiryoguran et al. [48] |

Chills or hot flushes |

Anxiety disorder: HADS-A score (cut-off ≥10) |

31 |

4.85 |

0.81 |

| Demiryoguran et al. [48] |

Fear of dying |

Anxiety disorder: HADS-A score (cut-off ≥10) |

31 |

4.04 |

0.82 |

| Demiryoguran et al. [48] |

Diaphoresis |

Anxiety disorder: HADS-A score (cut-off ≥10) |

31 |

3.49 |

0.69 |

| Demiryoguran et al. [48] |

Light-headedness, dizziness, faintness |

Anxiety disorder: HADS-A score (cut-off ≥10) |

31 |

3.03 |

0.84 |

| Demiryoguran et al. [48] |

Palpitation |

Anxiety disorder: HADS-A score (cut-off ≥10) |

31 |

1.54 |

0.83 |

| Demiryoguran et al. [48] |

Shortness of breath |

Anxiety disorder: HADS-A score (cut-off ≥10) |

31 |

1.30 |

0.92 |

| Demiryoguran et al. [48] |

Nausea or gastric discomfort |

Anxiety disorder: HADS-A score (cut-off ≥10) |

31 |

1.98 |

0.90 |

| Foldes-Busque et al. [49] |

The Panic Screening Score (derivation population); does the patient have a history of anxiety disorders? Please indicate how often this thought occurs when you are nervous: ‘I will choke to death’. Did the patient arrive in the ED by ambulance? Please answer the statement by circling the number that best applies to you: ‘When I notice my heart beating rapidly, I worry that I might be having a heart attack’. Sum score 22, A total score ≥6 indicates probable panic. |

Panic disorder Diagnosis (structured Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) (ADIS-IV)) |

42 |

3.89 |

0.44 |

| Foldes-Busque et al. [49] |

The Panic Screening Score (validation population). |

Panic disorder diagnosis (structured ADIS-IV) |

43 |

3.44 |

0.55 |

| Fleet et al. [50] |

Panic disorder diagnosis: formula including Agoraphobia Cognitions QA, Mobility Inventory for Agoraphobia, Zone 12 Dermatome Pain Map, Sensory McGill Pain QA, Gender, Zone 25 (validation population) |

Panic disorder (ADIS-R structured interview by psychologist) |

23 |

2.60 |

0.46 |

| Katerndahl et al. [51] | GP diagnosis of panic disorder | Panic disorder (structured clinical interview of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, based on DSM-III-R) | 55 | 0.82 | 1.02 |

LR+: >10; LR-: <0.1; good: LR + 5 to 10, LR- 0.1 to 0.2; fair: LR + 2 to 5, LR- 0.2 to 0.5; poor: LR + 1 to 2, LR- 0.5 to 1.

aBiomechanical dysfunction defined as chest pain presumably caused by mechanical joint and muscle dysfunction related to C4 to Th8 somatic structures of the spine and chest wall established by means of joint-play and/or end-play palpation.

Reference tests are as follows. Endoscopic classification: LA classification: grade A, ≥1 mucosal break ≤5 mm, that does not extend between the tops of two mucosal folds; grade B, ≥1 mucosal break >5 mm long that does not extend between the tops of two mucosal folds; grade C, ≥1 mucosal break that is continuous between the tops of two or more mucosal folds but which involves <75% of the circumference; grade D, ≥1 mucosal break which involves at least 75% of the esophageal circumference [52]. Savary-Miller system: grade I, single or isolated erosive lesion(s) affecting only one longitudinal fold; grade II multiple erosive lesions, non-circumferential, affecting more than one longitudinal fold, with or without confluence; grade III, circumferential erosive lesions; grade IV, chronic lesions: ulcer(s), stricture(s) and/or short esophagus. Alone or associated with lesions of grades 1 to 3; grade V, columnar epithelium in continuity with the Z line, non-circular, star-shaped, or circumferential. Alone or associated with lesions of grades 1 to 4 [53]. Hentzel-Dent grades: grade 0, no mucosal abnormalities; grade 1, no macroscopic lesions but erythema, hyperemia, or mucosal friability; grade 2, superficial erosions involving <10% of mucosal surface of the last 5 cm of esophageal squamous mucosa; grade 3, superficial erosions or ulceration involving 10% to 50% of the mucosal surface of the last 5 cm of esophageal squamous mucosa; grade 4, deep peptide ulceration anywhere in the esophagus or confluent erosion of >50% of the mucosal surface of the last 5 cm of esophageal squamous mucosa [54]. pH-metry: De Meester criteria: (1) total number of reflux episodes; (2) number of reflux episodes with pH <4 for more than 5 minutes; (3) duration of the longest episode; (4) percentage total time pH <4; (5) percentage upright time pH <4; and (6) percentage recumbent time pH <4. [55]. Manometry: Spechler criteria is diagnosis of ineffective esophageal motility, nutcracker esophagus, spasm, achalasia based on basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure, relaxation, wave progression, distal wave amplitude [56].

24-h pH-metry 24-h pH monitoring, GERD gastroesophageal reflux disease, GP general practitioner, IHD ischemic heart disease, QA questionnaire, Sensory McGill McGill Pain Questionnaire sensory subscale, SIS symptom index score calculated by adding the reported daily severity (mild = 1; moderate = 2; severe = 3; and disabling = 4) multiplied by the reported daily frequency values during each week).

Patients with the main complaint of NCCP were less likely to have GERD (LR + 0.83, 0.43; LR- 1.13, 1.23) compared to patients with the main complaint of dysphagia (LR + 1.27, 1.16; LR- 0.97, 0.97) or GERD typical symptoms without chest pain (LR + 1.26, 1.53; LR- 0.93, 0.74) in two studies [25,26]. Two further studies compared the accuracy of NCCP and typical GERD symptoms (LR + 2.70 [27], 2.75 [24]; LR- 0.42 [24], 0.78 [27]) with NCCP without GERD symptoms (LR + 0.49; LR- 2.71 [24]) or with NCCP and a history of heart burn (LR + 2.15; LR- 0.74 [27]).

Accuracy of response to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment for diagnosis of GERD in NCCP

The effect of treatment with PPI was measured by using a symptom intensity score (SIS) at baseline and follow-up. The SIS was calculated by adding the reported daily severity (mild = 1; moderate = 2; severe = 3; and disabling = 4) multiplied by the reported daily frequency values obtained during each week of symptom recording.

Table 2 summarizes the results. Three studies compared the treatment response after high doses of PPI (rabeprazole [31], lansoprazole [32], omeprazole [33]) for 1 week to placebo. A reduction of the SIS score of ≥50% was associated with a good LR + and a fair LR- (LR + 5.48 [33], 7.13 [31], 8.56 [32]; LR- 0.24 [32], 0.25 [33], 0.28 [31]) for the presence or absence of GERD. The likelihood ratios in the placebo groups with a reduction of the SIS score of ≥50% were: LR + 0.89 [31], 0.61 [32], 3.04 [33]; LR- 1.03 [31], 1.22 [32], 0.84 [33]. A reduction of the SIS score of ≥65% resulted in a very good LR + (18.33), and a good LR- (0.17) [32]. A treatment duration of 4 weeks (lasoprazole) resulted in a better LR- (LR + 2.75; LR- 0.13) [36] when compared to 2 weeks (omeprazole [34], LR + 2.7; LR- 0.15).

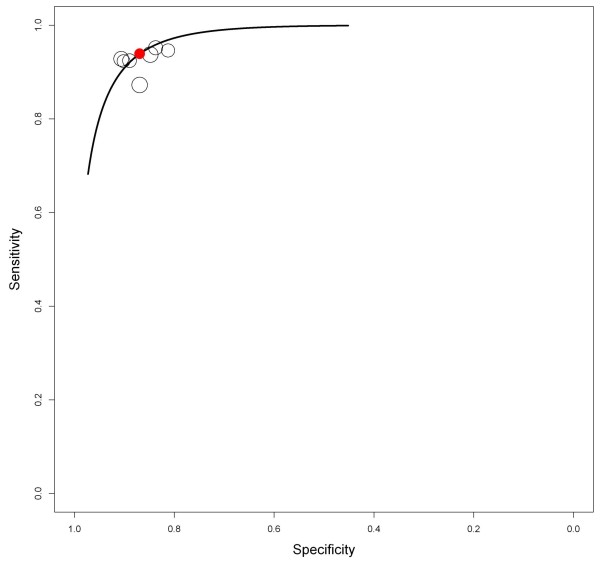

For joint meta-analysis only studies were considered with similar study design. Therefore, the active treatment arms of six studies were available for further analysis [31-36]. The model could be extended to include study-specific covariates such as the percentage of female patients or mean age to reduce unexplained heterogeneity on study level. However, due to the small number of studies available for pooling we refrained from including covariates. Figure 2 shows the summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Considering the GERD prevalence and the fact that no perfect reference test is available for GERD (sensitivity of the 24-h pH-metry in endoscopy-negative patients <71% [57]), the posterior mean sensitivity of what was 0.89 (95% credible interval, 0.28 to 1). The posterior mean of the specificity was 0.88 (95% credible interval, 0.26 to 1), respectively.

Figure 2.

Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) studies.

Accuracy of provocation tests for GERD diagnosis

Using a treadmill test during the 24-h pH-metry (reference test) showed highest LR + for GERD when chest pain was provoked by exercise (LR + 14.4; LR- 0.79 [39]). In all patients who underwent treadmill test, a high number of false negative test results during the treadmill test were observed.

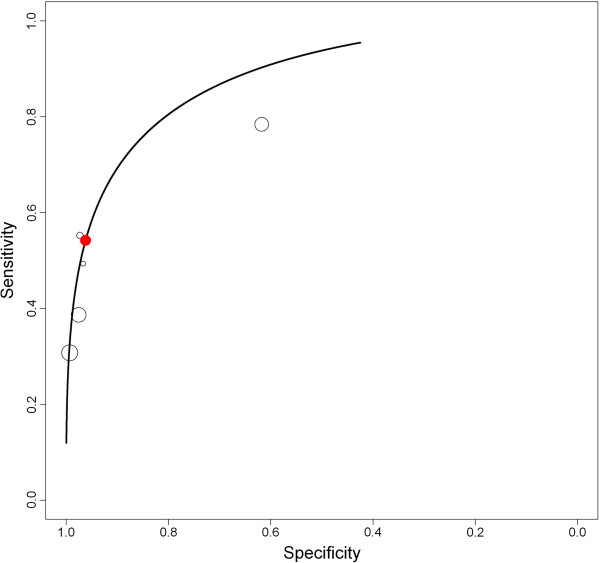

For joint meta-analysis only studies were considered with similar study design, again. Five patient groups from four original studies were included in the analysis [38-41]. Figure 3 shows the summary ROC curve. Considering the prevalence and imperfect nature of the reference test, posterior mean sensitivity and specificity were 0.53 (95% credible interval, 0.02 to 1) and 0.93 (95% credible interval, 0.25 to 1), respectively. For all provocation tests (Tensilon test, Bernstein test, or balloon distension test) high numbers of false negative results were found [29,42].

Figure 3.

Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) for treadmill test during 24 h pH-metry.

Accuracy of patient characteristics for eosinophilic esophagitis diagnosis

Eosinophilic esophagitis is a rare but important differential diagnosis for NCCP. In a retrospective analysis the likelihood for histologically proven eosinophilic esophagitis (reference test) was fair when current GERD symptoms were present (LR + 2.36, LR- 0.71 (poor)). Male gender or the presence of typical endoscopic findings for eosinophilic esophagitis were associated with a poor LR + (1.78) but a very good LR- (0.09) No information was available about eosinophilia that responds to PPI treatment compared to eosinophilic esophagitis.

Accuracy of clinical signs for musculoskeletal chest pain diagnosis

In one study in a cardiology emergency department specific clinical signs or symptoms compared to a standardized examination protocol showed either fair LR + and poor LR- (for example, pain worse with movement of the torso, pain relief on pain medication, no sudden pain start, age ≤49 years) or a poor LR + and a very good LR- (for example, anterior chest wall tenderness, biomechanical dysfunction) [44]. A score of 3 or more points in a sum score (1 point for each of five palpation findings: restriction in C4 to 7/Th1 to Th8 when sitting; prone restriction Th1 to 8; paraspinal tenderness; anterior chest wall tenderness; costosternal junction tenderness) showed an LR + of 1.52 and very good LR- of 0.03. A score of 1 or more points in a sum score for the diagnosis of a chest wall syndrome (CWS) in the GP setting (1 point for each positive finding: localized muscle tension; stinging pain; pain reproducible by palpation; absence of cough) showed a LR + of 1.82 and LR- of 0.20 [45]. A score of 2 or more points in the sum score showed a LR + of 3.02 and LR- of 0.47.

Accuracy of patient characteristics for psychiatric disease diagnosis

For the diagnosis of an anxiety disorder the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS-A, cut-off ≥8) compared to a neuropsychiatric interview (reference test) showed a very good LR- (0.03) and a fair LR + (2.03). In further studies the HADS-A was used as reference test for the diagnosis of anxiety disorder. Specific symptoms showed a fair LR + and a poor LR-: fear of dying (LR + 4.04; LR- 0.82); light-headedness, dizziness, or faintness (LR + 3.03; LR- 0.84); diaphoresis (LR + 3.49; LR- 0.69); and chills or hot flushes (LR + 4.85; LR- 0.81).

For panic disorders a four-item panic screening score validated in patients presenting to an ER showed fair LR + (3.44 and 3.89) and poor-to-fair LR- (0.44 and 0.55) [49]. A combination of different questionnaires and pain patterns (Agoraphobia Cognitions Questionnaire; Mobility Inventory for Agoraphobia; McGill Pain Questionnaire sensory) showed a fair LR + (2.6) and fair LR- (0.46) [50]. In patients presenting to their primary care physician with NCCP the presence of a panic disorder was rarely diagnosed. Clinician consultations in this setting had poor accuracy for panic disorder diagnosis (LR + 0.8; LR- 1.02) [51].

Discussion

Main findings

The included studies showed that most studies investigated tests for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as the underlying disease in non-cardiovascular chest pain (NCCP). Few studies investigated diagnostic tests for other illnesses. The diagnostic value of a PPI treatment test was confirmed, with a ≥50% symptom reduction under PPI treatment showing posterior sensitivity and specificity of almost 90%. Together with the favorable adverse effect profile of PPIs, a high dose (double reference dose, twice daily) can quickly provide important diagnostic information in patients with unexplained chest pain. History or presence of typical GERD-associated symptoms increases the likelihood of GERD.

Only limited evidence was available for other prevalent illnesses manifesting with chest pain. Screening tools for panic and anxiety disorders are valuable for identifying patients requiring further diagnostic evaluation. The likelihood for musculoskeletal chest pain increased when the pain was reproducible or relieved by pain medication. Among studies investigating musculoskeletal disease, the major limitation was the lack of a reference test (‘gold standard’).

Results in light of existing literature

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review summarizing the current evidence on the accuracy of diagnostic tests in patients with NCCP. Several non-systematic reviews have suggested various diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [14,58-61], often with algorithms focused on gastrointestinal diseases [14,58,59], sometimes recommending extensive testing, such as provocation tests. Here, we found no additional value of provocation testing for diagnosing underlying gastroesophageal conditions, as provocation tests failed to identify many patients that would have reflux during a 24-h pH measurement period. While meta-analyses of PPI treatment studies compared to placebo have been previously conducted [62,63], compared to this analyses we excluded studies of poor quality and small sample sizes [64-67]. Our study is the first to assess study quality and to use a hierarchical Bayesian approach that accounts for within-study and between-study variability and the imperfect nature of the reference test.

Cremonini et al. [62] previously used a bivariate model, and found a lower pooled sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity 80% vs 89%, specificity 74% vs 88%) of a positive PPI treatment response for the diagnosis of GERD. Harbord et al. [68] showed that the likelihood functions of the two model formulations are algebraically identical in the absence of covariates. However, for assessing a summary ROC curve, the hierarchical Bayesian model is more natural than the model for pooled sensitivity and specificity [69]. Without a broadly accepted standard reference test, it is important to adjust for conditional dependence between multiple tests (index test and reference test) carried out in the same subjects [69]. The hierarchical Bayesian model can be adapted to this situation by introducing covariance terms between the sensitivities and specificities of the index and reference tests. A previous simulation study [69] demonstrated that if a model does not address an imperfect reference test, bias will be around 0.15 in overall sensitivity and specificity [69]. No systematic review has examined diagnostic studies of musculoskeletal chest pain or chest pain as part of a psychiatric disease.

Strengths and limitations

This review comprehensively evaluates the currently available studies. The search was inclusive, no language restrictions were applied, and a thorough bibliographic search was conducted to identify all relevant studies. The extraction process was performed in accordance with current guidelines and supported by an experienced statistician. Potential factors influencing diagnostic test accuracy were identified by a multidisciplinary team (an internist, general practitioner, statistician, and methodologist).

The study was limited by the small number of studies available for most diseases presenting with NCCP. Furthermore, many studies were only of moderate quality and most cross-sectional or prospective studies did not meet the required sample size criterion for reliable estimates of sensitivity and specificity. Small studies on diagnostic accuracy are often imprecise, with wide confidence intervals, making it difficult to assess test informativeness [17]. The lack of a gold standard reference test is another limitation, which we addressed within the Bayesian model formulation; however, the resulting posterior credible intervals for overall sensitivity and specificity of the index test are wider than they would be with a perfect reference test. Further, NCCP is a collective term with potentially different underlying diseases and therefore might present differently. Diagnostic accuracy in one population with high prevalence for one disease is high might be entirely different for another population [70]. Therefore, for most studies no joint meta-analysis could be conducted and results have to be interpreted on a single study level within the context of the study population. We have tried to balance this by providing a thorough description of the studies’ inclusion and exclusion criteria and the study setting. This will allow readers to judge to whom study results apply. In studies included in the joint meta-analyses, we intended to include study-specific covariates such as the percentage of female or mean age into the Bayesian model. The inclusion of covariates can reduce unexplained heterogeneity. However, this was due to the small number of studies available for meta-analysis not feasible.

Research implications

Further research should investigate the combined value of symptoms, clinical findings, and diagnostic tests, including multidisciplinary research aimed at increasing our knowledge about diagnostic processes and making recommendations for diagnostic tests and treatments in patients with NCCP. Most patients with chest pain consult primary care physicians [45], but few studies are performed in this setting. Further research is needed to strengthen the evidence in a primary care setting. The value of screening questionnaires for panic and anxiety disorders should be further evaluated and investigated in clinical practice. The use of a flag system [61], as successfully applied in back and neck pain, could facilitate the diagnostic process allowing systematic assessment of first red flags (acute disease requiring immediate diagnosis and care), then green flags (identifiable diseases), and yellow flags (psychological diseases).

Implication for practice

Patients with NCCP incur high healthcare costs due to the extensive and often invasive diagnostic testing, and NCCP’s impact on quality of life. Early identification of underlying diseases is essential to avoid delayed treatment and chronicity of complaints. Symptoms and clinical findings may provide important information to guide treatment of an underlying illness. In patients with typical GERD symptoms, twice-daily high-dose PPI treatment is the most efficient diagnostic approach. GERD is very likely if a positive treatment response occurs after 1 week, while GERD is unlikely if there is no response after 4 weeks of PPI treatment. In patients not responding to PPI, if an endoscopy shows no pathological findings, other illnesses should be considered before initiating further gastrointestinal testing.

Panic and anxiety disorders are often missed in clinical practice [51]. Symptoms such as expressing ‘fear of dying’, ‘light headedness, dizziness, faintness’, ‘diaphoresis’ and ‘chills or hot flushes’ are associated with anxiety disorders. Screening tests are valuable to rule out panic or anxiety disorders, and positive finding should lead to further investigation.

Conclusions

In patients with NCCP, timely diagnostic evaluation and treatment of the underlying disease is important. A thorough history of symptoms and clinical examination findings can inform clinicians which diagnostic tests are most appropriate. Response to high-dose PPI treatment can indicate whether GERD is the underlying disease and should be considered as an early test. Panic and anxiety disorders are often not diagnosed and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of chest pain.

Appendix 1: Search Strategy May Week 4 2012

In Tables 3 and 4 the detailed search strategy of PubMed, Web of Knowledge (INSPEC, Biosis/Biological Abstracts, Web of Science) and OvidSP (Embase, PsycInfo) are given.

Table 3.

Search Strategy May Week 4 2012 (PubMed)

| No. | Search | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Search thoracic pain OR chest pain OR noncardiac chest pain OR non cardiac chest pain OR atypical chest pain OR musculoskeletal chest pain OR esophageal chest pain OR thoracic spine pain OR chest wall |

96,313 |

| 2 |

Search coronary artery disease OR cardiac disease OR coronary heart disease OR coronary thrombosis OR coronary occlusion |

929,959 |

| 3 |

Search 1 NOT 2 |

38,735 |

| 4 |

Search sensitivity OR specificity OR diagnostic tests OR chest pain/diagnosis |

1,301,595 |

| 5 |

Search 3 AND 4 |

2,736 |

| 6 |

Search 5 NOT 2; Filters: publication date from 1992/01/01; humans |

2,177 |

| 7 | Search 5 NOT 2; Filters: publication date from 1992/01/01; humans; adult: 19+ years | 1,432 |

Table 4.

Database: PsycINFO <1806 to May Week 4 2012>, Embase <1974 to 2012 Week 21> (OvidSP)

| No. | Search | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

(thoracic pain or chest pain or noncardiac chest pain or non cardiac chest pain or atypical chest pain or musculoskeletal chest pain or esophageal chest pain or thoracic spine pain or chest wall).mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tc, id, ot, tm, sh, tn, dm, mf, dv, kw] |

44,196 |

| 2 |

exp thorax pain/di [Diagnosis] |

2,481 |

| 3 |

exp thorax pain/ |

36,580 |

| 4 |

1 or 3 |

63,756 |

| 5 |

Coronary artery disease or cardiac disease or coronary heart disease or coronary thrombosis or coronary occlusion).mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tc, id, ot, tm, sh, tn, dm, mf, dv, kw] |

222,468 |

| 6 |

4 not 5 |

55,961 |

| 7 |

(sensitivity or specificity or diagnostic tests).mp. [mp = ti, ab, hw, tc, id, ot, tm, sh, tn, dm, mf, dv, kw] |

1,162,714 |

| 8 |

2 or 7 |

1,164,908 |

| 9 |

6 and 8 |

4,565 |

| 10 |

Limit 9 to human |

4,180 |

| 11 |

Limit 10 to year = ‘1992-Current’ |

3,778 |

| 12 |

Limit 11 to ‘300 adulthood < age 18 years and older > ‘ [Limit not valid in Embase; records were retained] |

3,769 |

| 13 | Limit 12 to adulthood <18+ years > [Limit not valid in Embase; records were retained] | 3,769 |

Biological Abstracts/BIOSIS, INSPEC and Web of Science (Web of Knowledge)

Topic = (‘thoracic pain’ OR ‘chest pain’ OR ‘noncardiac chest pain’ OR ‘non cardiac chest pain’ OR ‘atypical chest pain’ OR ‘musculoskeletal chest pain’ OR ‘esophageal chest pain’ OR ‘thoracic spine pain’ OR ‘chest wall’) AND Topic = (sensitivity OR specificity OR diagnostic tests) NOT Topic = (coronary artery disease OR cardiac disease OR coronary heart disease OR coronary thrombosis OR coronary occlusion)

Refined by: Topic = (human*)

Timespan = 1992 to 2012.

Appendix 2: Set up of the hierarchical Bayesian models for the summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves

Model 1: proton pump inhibitor (PPI) studies

Assumption: imperfect reference standard

Prior distributions:

Prior of prevalence (pi) is beta (12, 12), <= > pi in [0.3, 0.7]

Prior of beta is uniform (−0.75, 0.75)

Prior of THETA is uniform (−1.5, 1.5)

Prior of LAMBDA is uniform (−3, 3)

Prior of sigma_alpha is uniform (0, 2)

Prior of sigma_theta is uniform (0, 2)

Prior of S2 (sensitivity of reference test) is:

Study(ies) 1 to 7 beta (172.55, 30.45), <= > S2 in [0.8, 0.9]

Prior of C2 (specificity of reference test) is:

Study(ies) 1 to 7 beta (50.4, 12.6), <= > C2 in [0.7, 0.9]

Model 2: exertional 24 h pH-metry

Assumption: imperfect reference standard

Prior distributions:

Prior of prevalence (pi) is beta (5.2318, 6.0194), <= > pi in [0.18, 0.75]

Prior of beta is uniform (−0.75, 0.75)

Prior of THETA is uniform (−1.5, 1.5)

Prior of LAMBDA is uniform (−3, 3)

Prior of sigma_alpha is uniform (0, 2)

Prior of sigma_theta is uniform (0, 2)

Prior of S2 (sensitivity of reference test) is:

Study(ies) 1 to 5 beta (172.55, 30.45), <= > S2 in [0.8, 0.9]

Prior of C2 (specificity of reference test) is:

Study(ies) 1 to 5 beta (50.4, 12.6), <= > C2 in [0.7, 0.9]

Appendix 3: Summary of excluded studies during full-text review

In Table 5 summarizes the studies reviewed in full-text and excluded from the systematic review. For each study the reason for exclusion is provided.

Table 5.

Summary of excluded studies during full-text review

| Author | Year | Design | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aanen |

2008 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. No NCCP. GERD, reproducibility of reflux symptoms only |

| Abbass |

2009 |

randomised clinical trial |

No diagnostic study. No NCCP. General pain patients |

| Achem |

1993 |

retrospective, review |

Prevalence of nutcracker esophagus in NCCP. For treatment outcome open label trial with small sample |

| Achem |

1997 |

randomised, controlled trial |

No diagnostic study. GERD patients only received PPI |

| Achem |

2000 |

review article |

Review article about atypical chest pain |

| Adams |

2001 |

retrospective review |

no NCCP. Spiral CT in pulmonary embolism |

| Adamek |

1995 |

cross-sectional study |

No reference test. Description of coexistence of motility disorders and pathologic acid reflux |

| Aikens |

2001 |

cross-sectional study |

No diagnostic study, presence of fear in NCCP patients. Correlation of fear with symptoms |

| Aizawa |

1993 |

cross-sectional study |

no NCCP, acetylcholine provocation test for coronary arterial spasm |

| Ajanovic |

1999 |

cross-sectional study |

no NCCP. Pulmonary embolism |

| Aksglaede |

2003 |

experimental |

Experimental. Small sample (n = 5) chest pain. |

| Alexander |

1994 |

cross-sectional study |

Prevalence and nature of mental disorders in NCCP and IHD |

| Amarasiri |

2010 |

cross-sectional study |

GERD patients not NCCP |

| Anzai |

2000 |

cross-sectional study |

No reference test, coronary flow reserve with dopler in patients with no significant coronary stenosis |

| Armstrong |

1992 |

review article |

Review article about atypical chest pain |

| Arnold |

2009 |

randomised clinical trial |

No diagnostic study. Treatment outcome |

| Aufderheide |

1996 |

validation |

Validation of ACI-TIPI probabilities for MI |

| Bak |

1994 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. Comparison of prevalence of findings |

| Balaban |

1999 |

experimental |

No diagnostic study. Small sample (n = 10) |

| Baniukiewicz |

1997 |

cross-sectional study |

No diagnostic study. Description of findings in upper GI studies |

| Barham |

1997 |

observational |

No NCCP. Description of presence of esophageal spasm in patients undergoing upper GI studies |

| Barki |

1996 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. Description of clinical presentation in painful rip syndrome |

| Basseri |

2011 |

experimental |

Experimental. No NCCP. Different techniques swallow studies |

| Bassotti |

1998 |

cohort, retrospective |

No NCCP. Nutcracker esophagus and the symptoms and findings investigated. |

| Bassotti |

1992 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. Prevalence |

| Beck |

1992 |

cross-sectional study |

No diagnostic study. Charasteristics of NCCP patients compared to general pain patients |

| Belleville |

2010 |

cross-sectional study |

No diagnostic study. Characteristics of patients with panic disorders in the ER |

| Berkovich |

2000 |

cohort, retrospective |

No NCCP |

| Bernstein |

2002 |

validation |

GOLDmineR: improvement of a risk model |

| Berthelot |

2005 |

cohort, retrospective |

No diagnostic study. Pain referral study after injection |

| Bjorksten |

1999 |

cross-sectional study |

No patients, workers with muscoloskeletal complaints |

| Blatchford |

1999 |

cross-sectional study |

No NCCP. Emergency medical admission rates |

| Borjesson |

1998 |

cross-sectional study |

Small sample (n = 18), prevalence of esophageal findings |

| Borjesson |

1998 |

non-randomised controlled trial |

No diagnostic study. Small sample size (n = 20 per group). Intervention = TENS |

| Bortolotti |

2001 |

experimental |

No diagnostic study, small sample (n = 9) |

| Bortolotti |

1997 |

randomised clinical trial |

No diagnostic study. L-Arginine in patients with NCCP. Small sample (n = 8) |

| Bovero |

1993 |

cohort, prospective |

Duplicate of same study Bovero 1993 included in the analysis under different titel |

| Bovero |

1993 |

cohort, prospective |

Duplicate of same study Bovero 1993 included in the analysis under different titel |

| Brims |

2010 |

review article |

Review article about atypical chest pain |

| Broekaert |

2006 |

experimental |

Experimental trial in volunteers (no patients, n = 10) |

| Brunse |

2010 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. Prevalence |

| Brusori |

2001 |

cross-sectional study |

Mixed sample, diagnosis of esophageal dysmotility in fluoroscopy vs. Manometry |

| Budzynski |

2010 |

cross-sectional study |

Mixed patients sample with significant and non significant coronary leasons not responding to PPI treatment |

| Bruyninckx |

2009 |

cross-sectional study |

No diagnostic study. GP's reasons for referral |

| Cameron |

2006 |

case series |

Case series, selected sample by gastroenterologist. Not all patients had all investigation. Small samples for each group |

| Cannon |

1994 |

randomised clinical trial |

Treatment outcome (imipramine vs. placebo) |

| Carter |

1997 |

review article |

Review article about atypical chest pain |

| Cremonini |

2005 |

review article |

Systematic Review PPI |

| Castell |

1998 |

Editorial |

Editorial |

| Chambers |

1998 |

observational |

Small sample size: n = 23, SI in 7 patients not calculated |

| Cheung |

2007 |

cross-sectional study |

No diagnostic study. Questionnaire to doctors to see what kind of patients they see, what diagnostic tests they use and how they treat. |

| Christenson |

2004 |

cohort, prospective |

Chest discomfort inappropriately not diagnosed ACS. Different research question |

| Crichton |

1997 |

experimental |

Experimental statistical rule out |

| Cossentino |

2012 |

randomised clinical trial |

No diagnostic study. Baclofen in gastro-esophageal diseases |

| Dekel |

2003 |

cohort, retrospective |

No diagnostic study. Prevalence of esophageal motility disorders. |

| Dekel |

2004 |

Not randomised, not controlled trial |

PPI trial only 14 patients included (only GERD positive treated) |

| Deng |

2009 |

cross-sectional study |

No NCCP. Combination between cardiac ischemia and esophageal spasms |

| De Vries |

2006 |

cross-sectional study |

Mixed patient sample with cardiac and non-cardiac chest pain |

| Dickman |

2007 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. Prevalence of GI findings in NCCP vs. patients with GERD |

| Disla |

1994 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study, prevalence |

| Domanovits |

2002 |

cross-sectional study |

Rule out cardiovascular disease. No diagnostic study for NCCP |

| Ellis |

1992 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. Treatment outcome in patients with esophageal spasm |

| Elloway |

1992 |

cross-sectional study |

provocative radionuclide esophagealNo comparison to reference test, radionuclide esophageal transit (P-RET) investigation, small sample (n = 30) |

| Elloway |

1992 |

cross-sectional study |

Same study under different title |

| Erhardt |

2002 |

Guideline |

Task force on the management of chest pain |

| Esayag |

2008 |

retrospective review |

Pleuritic chest pain. No reference test, description of presentation and outcome |

| Esler |

2001 |

randomized clinical trial |

Dissertation, same as following. |

| Esler |

2003 |

randomized clinical trial |

Treatment intervention in NCCP. CBT in NCCP seems to reduce chest pain episodes |

| Fass |

1999 |

cohort, prospective |

No diagnostic study. Treatment outcome study |

| Fleischmann |

1997 |

cross-sectional study |

No NCCP. Echokardiographic findings in acute chest pain and health status |

| Fletcher |

2011 |

cohort, prospective |

Sample size: 8 patients with NCCP |

| Fornari |

2008 |

cohort, retrospective |

No NCCP. Only nutcracker esophagus investigated |

| Fournier |

1993 |

cross-sectional study |

No NCCP. Ergovine test during coronary angiogram and induction of coronary spasm |

| Fournier |

1993 |

cross-sectional study |

Same study under different titles |

| Foldes |

2011 |

cross-sectional study |

No comparison of test with reference test. Prevalence of panic disorders |

| Frobert |

1996 |

cross-sectional study |

No diagnostic study. Comparison of characteristics between NCCP with positive treadmill test compared to negative treadmill test. |

| Gentile |

2003 |

cross-sectional study |

Patients with pneumococcal pneumonia. No reference test, description of presentation, microbiological findings and mortality |

| Gignoux |

1993 |

experimental |

No diagnostic study, experimental study |

| Goehler |

2011 |

experimental |