Abstract

This is the first study to investigate whether parent-reported social and behavioral problems on the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) can be used for psychosis risk screening and the identification of at-risk youth in the general population. This longitudinal investigation assessed 122 adolescent participants from three groups (at-risk, other personality disorders, nonpsychiatric controls) at baseline and one year follow-up. The findings indicate that two individual CBCL rating scales, Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems, have clinical and diagnostic utility as an adjunctive risk screening measure to aid in early detection of at-risk youth likely to develop psychosis. Furthermore, the findings shows that a cost-effective, general screening tool with a widespread use in community and pediatric healthcare settings has a promise to serve as a first step in a multi-stage risk screening process. This can potentially facilitate increased screening precision and reduction of high rate of false-positives in clinical high-risk individuals who present with elevated scores on psychosis-risk measures, but ultimately do not go on to develop psychosis. The findings of the present study also have significant clinical and research implications for the development of a broad-based psychosis risk screening strategy, and novel prevention and early intervention approaches in at-risk populations for the emergence of severe mental illness.

Keywords: Psychosis risk, Clinical high-risk, Prodrome, Adolescents, CBCL, Screening, Early intervention, Prevention

1. Introduction

In recent years, increased research attention has been focused on the identification and improvement of psychosis risk screening methods in at-risk populations. An extensive body of research provides evidence for social and behavioral precursors of vulnerability to psychosis long before the illness onset (Cornblatt, 2002; Erlenmeyer-Kimling, 2000; Johnstone et al., 2000; Nuechterlein and Dawson, 1984; Olin and Mednick, 1996). It is estimated that at least 70% of patients with schizophrenia manifest behavioral problems during adolescence (Cannon et al., 1999; Neumann et al., 1995). Early adulthood is the modal period for the onset of psychosis (Neumann and Walker, 2003). The premorbid indicators of vulnerability include schizotypal symptoms, such as social withdrawal and thought abnormalities (Walker et al., 1999), deficits in memory and executive function (Silverstein et al., 2003), neurological soft signs (Neumann and Walker, 2003), movement abnormalities (Mittal et al., 2007), and other. Also, the majority of individuals who succumb to psychotic disorders manifest prodromal signs of behavioral disturbance (Larsen et al., 1996; Neumann et al., 1995).

The general pattern of findings suggest that pre-psychotic youth are more socially isolated, withdrawn, emotionally labile, anxious, and aggressive than their healthy siblings and/or age-matched comparison subjects. They also have higher levels of impaired attention, which remain stable and elevated from childhood to adolescence, and are assumed to negatively affect social interactions leading to increased stress related to social situations (Cornblatt et al., 1997; Amminger et al., 1999; Hans et al., 2000; Miller et al., 2002; Ballon et al., 2007). The divergence in developmental trajectories becomes more pronounced with age and is especially apparent in the adolescent period. Research findings also suggest that the behavioral expression of vulnerability to psychosis is characterized by sex differences, with males exhibiting more externalizing behavior problems, while females exhibiting more internalizing behavior problems (Walker et al., 1995; Neumann et al., 1995; Gutt et al., 2008).

Given evidence that early identification and treatment can prevent or delay the transition to psychotic illness (Stafford et al., 2013), efforts to enhance early intervention and prevention methods have become a central focus of attention. Clinician-administered assessments such as the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes (SIPS; Miller et al., 2002, 2003) and the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (CAARMS; Yung et al., 2005) have been the standard measures used in specialty research clinics for early detection of patients at risk for psychotic illness. These measures, however, require substantial time for clinician training and patient participation, and are unlikely to be widely adopted in general clinical settings. One feasible strategy to enhance broad-based community screening of individuals at risk for psychosis is to assess the clinical and diagnostic utility of existing and widely used mental health screening tools. For instance, results from a recent study indicate that the Atypicality scale of the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds and Kamphaus, 2004) may be a useful measure for identifying youth in the early stages of psychosis (Thompson et al., 2013). Another study used the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) to assess its utility to distinguish within a clinical high-risk group of adolescents, individuals who subsequently converted to psychosis compared to those who did not convert (Simeonova et al., 2011). The findings indicate that within a clinical high-risk sample, the CBCL did not show promise as an alternative or adjunctive predictor of conversion to psychosis. No investigations, however, exist on whether the CBCL holds promise for the identification of at-risk youth in the general population. This is a feasible line of investigation, because the CBCL is a parent-report measure with extensive published normative data and its reliability and validity are well established. Although this instrument was not intended to differentiate between individuals atrisk for psychosis and control groups, it has the potential to serve as an inexpensive adjunctive screening measure in clinical practice. Also, the findings of the present study could have important implications for psychosis risk assessments in a variety of youth-oriented settings such as high-school, community centers, pediatric healthcare practice, and other.

The purpose of the present study is to shed light on two research questions: 1) Do CBCL rating scales significantly differentiate between at-risk youth and control groups? 2) At what level of accuracy do selected CBCL rating scales correctly classify individuals based on risk status? It was hypothesized that at-risk youth will be rated by parents as exhibiting more pronounced social and behavioral problems on the CBCL when compared to control groups. It was also predicted that the differences between the groups will become more pronounced over time. The adolescent period is the focus of this study because it is characterized by a rapid increase in risk for psychosis onset, and it is likely to be a critical period for early intervention and prevention (Walker, 2002).

2. Methods

The study sample of 122 participants, ranging in age from 12 to 18 years, was enrolled in a prospective study at Emory University focused on neurobiological and behavioral aspects of clinical risk for psychosis in adolescents. The three diagnostic groups included 53 adolescents designated as at-risk (AR), 37 adolescents with other personality disorders (OPD), and 32 nonpsychiatric controls (NC) (mean age = 14.2; SD = 1.8), who underwent assessments at baseline and at one year follow-up and for whom a CBCL had been completed. Participants were designated to the AR group if they met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) (n=1), the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS) criteria for attenuated positive symptoms (APS) (n=13), or both risk criteria (n=39). Demographic characteristics by diagnostic group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of samples.

| AR | OPD | NC | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 53 | 37 | 32 | 122 |

| Males | 35 | 17 | 16 | 68 |

| Females | 18 | 20 | 16 | 54 |

| Age (yrs.) | ||||

| M | 14.17 | 14.59 | 14.00 | 14.25 |

| (SD) | (1.70) | (1.83) | (1.93) | (1.80) |

| Medications | ||||

| Stimulants | 10 | 4 | 3 | 17 |

| Antidepressants | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Antipsychotics | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| More than one medication category | 9 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| No medications | 29 | 29 | 29 | 87 |

AR=at-risk, OPD=other personality disorders, NC=normal controls

The following instruments were administered to all study participants: Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SIDP-IV) (Pfohl et al., 2001), Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-I) (First et al., 1995), Structured Interview for Prodromal Symptoms (SIPS) (Miller et al., 2002, 2003), and CBCL parent-report scale (Achenbach, 1991). For a detailed description of the methodology approach, please see the online Supplementary Materials section.

Multivariate-analyses of covariance (MANCOVA) and repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted with baseline and follow-up data to test the a priori hypotheses of the present study. Given that psychotropic medications can have an effect on behavioral characteristics, medication status was dummy-coded variable (0 = no medication, 1 = medication) and included in the analyses to control, separately for the three major classes of medications: stimulants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics. Also, given evidence of sex differences in behavioral problem symptoms in clinical samples, sex was examined as an independent variable in the statistical analyses. Assumptions for parametric tests were met, with normal sample distribution and appropriate homogeneity of variances and covariances. In addition, discriminant analysis was conducted with baseline CBCL data to determine at what level of accuracy the CBCL can classify participants correctly based on risk status.

The cross-temporal stability of the CBCL scales was examined with correlational analyses for the entire sample and for each diagnostic group. The analyses revealed significant positive inter-correlations across assessment periods (baseline and one year follow-up) within each CBCL scale. All p values were less than .05. These results suggest longitudinal stability of the ratings.

3. Results

3.1. Cross-sectional comparisons at Baseline

Analyses were first conducted to test for demographic differences among the three diagnostics groups. There were no significant age (F(2,119) = 1.03, p = .358) or sex differences (χ2 = 4.14, p = .349) between the groups.

The CBCL scores and significant group differences for the individual and composite scales are presented in Table 2. Consistent with the prediction, there were significant differences between the groups on the CBCL at baseline assessment. MANCOVA with the CBCL individual scales revealed a significant main effect for diagnostic status, Wilks's Λ = .61, F(22, 198) = 2.51, p = .000, η2 = .22. MANCOVA with the CBCL composite scales yielded similar findings with a significant main effect for diagnostic status, Wilks's Λ = .66, F(6, 216) = 8.09, p = .000, η2 = .18. Univariate tests results were partially consisted with predictions. The findings showed that diagnostic groups differed on all CBCL rating scales. The only scale that did not show group differences was Activities. Also, overall there were no significant differences between the AR and OPD groups across all CBCL (see Table 2).

Table 2.

CBCL individual scales mean T scores and standard deviations by diagnostic group at baseline assessment.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | OPD | NC | Group Differences | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| CBCL Individual Scales | ||||

| Activities ▲ | 42.90 (7.89) | 43.38(10.21) | 44.56 (9.99) | 1,2,3 = n.s. |

| Social ▲ | 37.19(9.00) | 37.91 (9.53) | 44.91 (12.01) | 1 < 3*,2< 3* |

| School ▲ | 38.08(8.58) | 40.41 (9.67) | 45.03 (8.71) | 1< 3* |

| Anxious/Depressed | 69.00 (12.02) | 63.24(10.09) | 56.28 (8.41) | 1 > 3**,2 > 3* |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 66.71 (11.40) | 62.59(8.98) | 56.59 (8.04) | 1 > 3** |

| Somatic Complaints | 63.21 (10.50) | 60.76 (8.32) | 54.66(6.81) | 1 > 3**, 2 > 3* |

| Social Problems | 69.02(11.09) | 62.15 (10.33) | 57.06 (9.76) | 1 > 3** |

| Thought Problems | 68.08 (9.79) | 63.32(9.72) | 58.19(9.84) | 1 > 3** |

| Attention Problems | 66.88 (8.96) | 63.21 (9.52) | 57.34 (8.94) | 1 >3**, 2 > 3* |

| Delinquent Behavior | 61.56(7.90) | 64.85 (11.16) | 56.16 (6.18) | 1 > 3*, 2 > 3** |

| Aggressive Behavior | 65.58 (10.61) | 67.32(11.60) | 57.69(10.28) | 2 > 3** |

| CBCL Composite Scales | ||||

| Total Competence ▲ | 36.33(8.12) | 37.11 (10.17) | 45.03 (10.35) | 1<2**, 9<3** |

| Internalizing Problems | 68.23 (9.98) | 62.97(10.34) | 51.38 (13.02) | 1 > 3**, 2>3** |

| Externalizing Problems | 63.23 (10.75) | 66.03 (11.13) | 53.00(12.63) | 1> 3**, 2>3** |

Note:

A high scores indicate more social competencies

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05

AR=at-risk, OPD=other personality disorders, NC=normal controls

The analyses revealed a main effect for stimulant medications, Wilks's Λ = .76, F(11, 99) = 2.85, p = .003, η2 = .24 (for individual CBCL scales) and Wilks's Λ = .91, F(3, 108) = 3.57, p = .016, η2 = .09 (for composite CBCL scales). The medication covariate was significant for the scales Withdrawn, F(1, 109) = 4.43, p = .038, η2 = .04, Social Problems, F(1, 109) = 8.53, p = .004, η2 = .07, Aggressive Behavior, F(1, 109) = 9.18, p = .003, η2 = .08, and Externalizing Problems F(1, 110) = 9.17, p = .003, η2 = .08. This effect was due to higher symptoms ratings for participants on stimulant medication.

There was no significant main effect or interaction effect of sex with diagnostic group on the CBCL scales.

3.2.Cross-sectional comparisons at One-Year Follow-Up

The CBCL scores and significant group differences for the individual and composite scales are presented in Table 3. Consistent with the prediction, there were significant diagnostic group differences between the AR group and the comparison groups at one year follow-up assessment. MANCOVA with the CBCL individual scales revealed a significant main effect for diagnostic status, Wilks's Λ = .58, F(22, 128) = 1.83, p = .021, η2 = .24. MANCOVA with the CBCL composite scales yielded similar findings with a significant main effect for diagnostic status, Wilks's Λ = .74, F(6, 144) = 3.85, p = .001, η2 = .14. Univariate tests results were consisted with predictions. The findings showed that diagnostic groups differed on all CBCL rating scales (see Table 3).

Table 3. CBCL individual scales mean T scores and standard deviations by diagnostic group at one-year follow-up assessment.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | OPD | NC | Group Differences | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| CBCL Individual Scales | ||||

| Activities ▲ | 43.69(7.38) | 39.93 (10.22) | 47.10(7.78) | 2<3* |

| Social ▲ | 38.63 (7.55) | 39.15(8.17) | 45.95(8.18) | 2<3* |

| School ▲ | 37.31 (8.16) | 40.78 (7.99) | 46.76 (8.58) | 1 <3* |

| Anxious/Depressed | 62.94(10.73) | 57.15(8.66) | 58.86(10.05) | 1,2,3 =n.s. |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 62.09 (10.72) | 56.07 (10.11) | 53.29(6.58) | 1 >3**, 1 >2* |

| Somatic Complaints | 60.74(11.43) | 55.78(8.39) | 52.29 (4.09) | 1 >3* |

| Social Problems | 65.51 (11.93) | 57.07 (8.62) | 55.29 (9.38) | 1,2,3 =n.s. |

| Thought Problems | 64.89 (8.97) | 57.11 (9.73) | 54.10(8.95) | 1 > 3**, 1 > 2** |

| Attention Problems | 65.74(10.86) | 59.59(9.78) | 55.48(8.71) | 1 >3* |

| Delinquent Behavior | 62.20 (8.86) | 59.59(8.21) | 55.76 (7.89) | 1,2,3 =n.s. |

| Aggressive Behavior | 62.43(10.17) | 59.04(10.73) | 54.29 (7.03) | 1 >3* |

| CBCL Composite Scales | ||||

| Total Competence ▲ | 37.37 (7.92) | 37.41 (10.30) | 47.33 (10.33) | 1 <3*, 2 <3** |

| Internalizing Problems | 62.03 (12.47) | 53.41 (11.62) | 47.14(10.86) | 1 >3**, 1 >2* |

| Externalizing Problems | 62.43(11.72) | 57.56 (11.35) | 50.00(11.96) | 1 >3* |

Note:

high scores indicate more social competencies

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .05

AR=at-risk, OPD=other personality disorders, NC=normal controls

The AR participants showed significantly higher scores on the Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems scales compared to the OPD participants.

There was a main effect for stimulant medication, Wilks's Λ = .70, F(11, 64) = 2.60, p = .008, η2 = .31, for individual CBCL scales, but no significant main effect for composite CBCL scales. The medication covariate was significant for the scales School, F(1, 74) = 10.67, p = .002, η2 = .13, Social Problems, F(1, 74) = 4.73, p = .033, η2 = .06, and Delinquent Behavior, F(1, 74) = 5.40, p = .023, η2 = .07. Those on stimulants showed worse CBCL ratings.

There was no significant main effect or interaction effect of sex on the CBCL scales.

3.3.Discriminant function

A discriminant function analysis was conducted with baseline CBCL data to determine at what level of accuracy the two predictors - the CBCL individual scales Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems - classify participants correctly based on risk status. The overall Wilks's lambda was significant, Λ = .79, χ2 = (4, N = 122) = 27.28, p = .000, indicating that overall the predictors differentiated among the three groups. The residual Wilks's lambda was not significant. Therefore, only the first discriminant function was interpreted.

The within-groups correlations between the predictors and the discriminant function as well as standardized weights are presented in Table 4. Based on these coefficients, scores on the Thought Problems scale demonstrate the strongest relationship with the discriminant function.

Table 4.

Correlations and standardized coefficients of predictor variables with one discriminant function.

| Predictors | Correlation coefficients with discriminant function | Standardized correlation coefficients for discriminant function |

|---|---|---|

| CBCL Scale Withdrawn/Depressed | .82 | .58 |

| CBCL Scale Thought Problems | .84 | .62 |

The means of the discriminant function are consistent with this interpretation. The AR group had the highest mean score, followed by the OPD and NC groups, respectively, on both CBCL scales. Also, when group membership was predicted, of the 53 cases in the AR group 33 (62%) were classified correctly.

A list of individual items contained in the CBCL scales Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

List of individual items for CBCL scales Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems.

| CBCL Scale Withdrawn/Depressed |

| 5. There is very little he/she enjoys |

| 42. Would rather be alone than with others |

| 65. Refuses to talk |

| 69. Secretive, keeps things to self |

| 75. Too shy or timid |

| 102. Underactive, slow moving, or lacks energy |

| 103. Unhappy, sad, or depressed |

| 111. Withdrawn, doesn't get involved with others |

|

|

| CBCL Scale Thought Problems |

| 9. Can't get his/her mind off certain thoughts; obsessions |

| 18. Deliberately harms self or attempts suicide |

| 40. Hears sound or voices that aren't there |

| 46. Nervous movements or twitching |

| 58. Picks nose, skin, or other parts of body |

| 59. Plays with own sex parts in public |

| 60. Plays with own sex parts too much |

| 66. Repeats certain acts over and over; compulsions |

| 70. Sees things that aren't there |

| 76. Sleeps less than most kids |

| 83. Stores up too many things he/she doesn't need |

| 84. Strange behavior |

| 85. Strange ideas |

| 92. Talks or walks in sleep |

| 100. Trouble sleeping |

3.4.Temporal progression of CBCL ratings

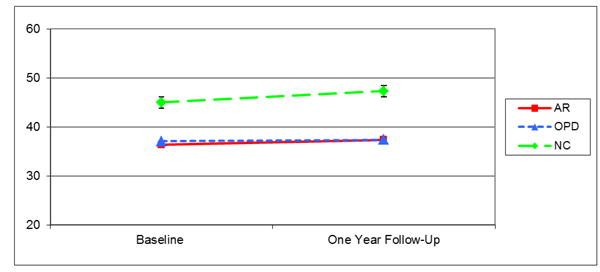

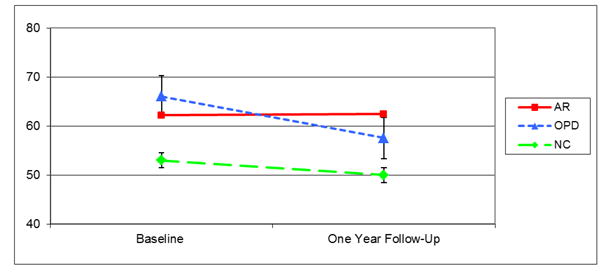

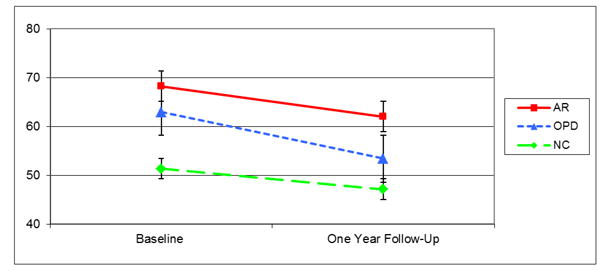

Figures 1 through 3 illustrate the temporal progression of CBCL composite scores - Total Competence, Internalizing Problems, and Externalizing Problems - from baseline to one year follow-up assessment. Repeated-measures ANCOVA was conducted on the 90 subjects for whom CBCL data were available at both baseline and follow-up. Consistent with the prediction, the analyses revealed a significant main effect for diagnostic status for the following individual and composite scales: Social, F(2, 79) = 6.80, p = .002, η2 = .15, School, F(2, 79) = 6.47, p = .003, η2 = .14, Anxious/Depressed, F(2, 80) = 5.48, p = .006, η2 = .12, Withdrawn/Depressed, F(2, 81) = 7.41, p = .001, η2 = .16, Somatic Complaints, F(2, 81) = 7.69, p = .001, η2 = .16, Social Problems, F(2, 81) = 4.45, p = .015, η2 = .10, Thought Problems, F(2, 81) = 12.52, p = .000, η2 = .24, Attention Problems, F(2, 81) = 8.54, p = .000, η2 = .17, Delinquent Behavior, F(2, 81) = 4.81, p = .011, η2 = .11, Aggressive Behavior, F(2, 81) = 5.00, p = .009, η2 = .11, Total Competence, F(2, 76) = 7.56, p = .001, η2 = .17, Internalizing Problems, F(2, 81) = 12.63, p = .000, η2 = .24, and Externalizing Problems, F(2, 81) = 6.92, p = .002, η2 = .15.

Figure 1. CBCL Total Competence scores by diagnostic group over time.

AR=at-risk, OPD=other personality disorders, NC=normal controls

Figure 3. CBCL Externalizing Problems scores by diagnostic group over time.

AR=at-risk, OPD=other personality disorders, NC=normal controls

Compared with the OPD adolescents, the AR adolescents had significantly higher scores on the scale Thought Problems and Delinquent Behavior. Compared with the NC group, the AR group had significantly lower scores on the scales Social, School, and Total Competence, and significantly higher scores on the scales Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Delinquent Behavior, Aggressive Behavior, Internalizing Problems, and Externalizing Problems. Finally, compared to the NC group, the OPD group had significantly lower scores on the scales Social, School, and Total Competence, and significantly higher scores on the scales Somatic Complaints, Delinquent Behavior, Aggressive Behavior, Internalizing Problems, and Externalizing Problems. Also, overall the OPD youth showed highest scores for the individual scales Delinquent Behavior and Aggressive Behavior, and the composite scale Externalizing Problems.

The stimulant medication covariate was significant for the scales School, F(1, 79) = 11.33, p = .001, η2 = .13, Social Problems, F(1, 81) = 13.84, p = .000, η2 = .15, Attention Problems, F(1, 81) = 6.06, p = .016, η2 = .07, Delinquent Behavior, F(1, 81) = 11.30, p = .001, η2 = .12, Aggressive Behavior, F(1, 81) = 12.32, p = .001, η2 = .13, and Externalizing Problems, F(1, 81) = 11.42, p = .001, η2 = .12, while the antipsychotic medication covariate was significant for the scale Thought Problems, F(1, 81) = 6.00, p = .016, η2 = .07. No effect was found for antidepressant medication. Furthermore, the analyses yielded a significant Antipsychotics X Time interaction for the scale Thought Problems, Wilks's Λ = .93, F(1, 81) = 6.03, p = .016, η2 = .07, and a significant Antidepressants X Time interaction for the scale Aggressive Behavior, Wilks's Λ = .95, F(1, 81) = 4.09, p = .047, η2 = .05. This was due to a significant decrease of problems from baseline to follow-up assessments for those not taking antipsychotic medication, t (82) = 2.25, p = .027, and both those not taking antidepressant medication, t (79) = 3.12, p = .003, and those taking antidepressant medication, t (9) = 2.58, p = .030.

There was a main effect for time for the following individual and composite CBCL scales: Anxious/Depressed, Wilks's Λ = .93, F(1, 80) = 5.88, p = .018, η2 = .07, Somatic Complaints, Wilks's Λ = .92, F(1, 81) = 7.57, p = .007, η2 = .09, Social Problems, Wilks's Λ = .92, F(1, 81) = 6.93, p = .010, η2 = .08, and Internalizing Problems, Wilks's Λ = .89, F(1, 81) = 9.07, p = .003, η2 = .10. The effect of time was due to decreasing social and behavioral problems over time. Although the time effect was not significant for the other CBCL scales, the overall trend across scales was toward a decline of problems over time.

These main effects were qualified by a significant Diagnostic Status X Time interaction for the following CBCL scales: Activities, Wilks's Λ = .91, F(2, 82) = 3.90, p = .024, η2 = .09, Aggressive Behavior, Wilks's Λ = .88, F(2, 81) = 5.11, p = .008, η2 = .11, and Externalizing Problems, Wilks's Λ = .86, F(2, 81) = 6.42, p = .003, η2 = .14. Paired sample t tests were conducted to follow-up on the significant interactions. Differences in mean ratings were significantly different between baseline and follow-up assessments, where OPD participants showed significant decreases on the scales Aggressive Behavior, t (28) = 5.32, p = .000 and Externalizing Problems, t (28) = 4.35, p = .000, and decrease in functioning over time on the scale Activities, t (29) = 2.56, p = .016. Similarly, although not significant, the AR participants' scores on the three scales followed this trend.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to investigate whether parent-reported social and behavioral problems on the CBCL can be used for psychosis risk screening and the identification of at-risk youth in the general population. The findings indicate that selected rating scales on the CBCL hold promise as possible predictors of risk and that these scales could serve as potential inexpensive adjunctive screening measure in clinical practice. While previous research has not shown evidence for the CBCL as useful screening instrument within a high-risk group of youth at risk for psychosis (converters vs. non-converters to psychosis) (Simeonova et al., 2011), the current study shows support for the rating scales Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems as useful in differentiating at-risk youth in the general population.

As expected, the cross-sectional comparisons at baseline and one-year follow-up assessments showed that AR youth have more social and behavioral problems compared to normal controls. The same was true for the OPD group compared to normal controls. Statistically significant group differences were present at one year follow-up assessment between the AR and OPD youth, with higher scores on the individual scales Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems and the composite scale Internalizing Problems for AR youth. This finding underscores that the scales Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems are most useful during a time period proximal to the time point of onset of prodromal symptoms and psychosis (in the present study: one year follow-up CBCL data) as opposed to distal to the onset of psychosis (in the present study: baseline CBCL data). Therefore, these two individual CBCL rating scales have the most potential to be beneficial for psychosis risk screening in the general population when the screening is conducted at a time point proximal to the mean risk age for onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms. Follow-up analyses on this finding using discriminant function determined that the scale Thought Problems is slightly better at discriminating between the groups compared to the scale Withdrawn/Depressed. The finding with the composite scale Internalizing Problems is driven by the differences on the scale Withdrawn/Depressed, given that this composite scale is comprised of the individual scales Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, and Somatic Complaints. On the other hand, descriptively, the mean baseline scores on the majority of CBCL rating scales of the AR group were in the expected direction and higher than the OPD group. These mean baseline differences, however, were not statistically significant. It is likely, though, that this might change with an increased sample size and increased power to detect differences. For instance, statistical power calculations showed that our study was underpowered to detect baseline group differences between the AR and OPD groups for the individual scales Withdrawn/Depressed (48% power) and Thought Problems (62% power).

Clinically and descriptively, it is important to examine the level of individual items comprising the scales Thought Problems and Withdrawn/Depressed. Although item level analyses should be avoided because of reliability issues at the item level, this has significant implications, as it offers insight into problem areas representing significant predictors for worsening of symptoms in youth at risk for development of prodromal and psychotic symptoms. This descriptive and detailed level of examination can narrow the scope of problem domains to be targeted in clinical treatment and provide a platform for the development of novel early interventions aimed at preventing/delaying the onset and progression of mental health problems in at-risk youth. Table 5 presents a complete list of the relevant CBCL items. The first scale, Withdrawn/Depressed, captures behaviors reflective of affective disturbance (i.e., social withdrawal, depression, sadness, and other), while the second scale, Thought Problems, captures behaviors reflective of thought disturbance (i.e., strange behaviors and ideas, hallucinations, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, and other). Therefore, the present findings suggest that these problems are indicative of the highest risk for onset and progression of psychotic illness in atrisk youth. Future studies with larger samples might benefit from employing a factor analytic approach to investigate further within scale factors with the highest potential to contribute to prediction of risk. Also, it seems that the scale Withdrawn/Depressed speaks to the potential relevance of negative symptoms, while the scale Thought Problems speaks, as expected, to relevance of positive symptoms in determining risk. Negative symptoms, though, as assessed by standard clinician-administered measures of prodromal symptomatology (i.e., SIPS) have not been a determining factor for psychosis risk prediction. Therefore, future studies might benefit from better parsing out this relationship.

The findings of this study indicate that the mean longitudinal trend across CBCL scales and within the three diagnostic groups was toward a decrease of social and behavioral problems over time. This finding is consistent with the literature on normative decrease of social and behavioral problems in the mid-adolescent period (Bongers et al., 2003, 2004; Dekker et al., 2007). There is variability within this general trend, with some participants manifesting stable or increasing behavioral problems. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that although the prospective analyses did not show a shift in behavior toward greater social and behavioral problems in AR youth over time, behavioral problems exhibited by the AR group remained significantly higher throughout the study than the other control groups. Furthermore, significant Diagnostic Status X Time interactions were found for the individual scales Activities and Aggressive Behavior, and for the composite scale Externalizing Problems. This was due to the magnitude of differences between the OPD group and the other groups, which grew over the period of one year. Similarly, although not significant, the AR group's scores followed this trend. In an interpretation of this finding, it is important to mention that the OPD comparison group was composed of adolescents who showed relatively high rates of conduct problems.

It is of interest to note the findings with respect to psychotropic medications and sex. While the present study was not intended to address directly questions about medication effects, the findings underscore that medication classes are differentially associated with behavior. Therefore, to better parse out the relationship between behavioral ratings and differences between AR youth and control groups, effects of psychotropic medications should be examined in future research on social and behavioral problems in clinical high-risk samples. Furthermore, although past research has indicated that the behavioral expression of vulnerability to psychosis is characterized by sex differences (Watt, 1978; Walker et al., 1989; Olin and Mednick, 1996; Done et al., 1994), this study did not demonstrate main or interactive effects of sex on CBCL behavioral ratings.

Recent research findings underscore the need for adjunctive screening measures to aid in early detection of at-risk youth likely to develop psychosis (Simeonova et al., 2011; Tarbox et al., 2013). This is a high priority research domain, given the significance for the development of novel prevention and early intervention approaches in at-risk populations for the emergence of severe mental illness. Additional research investigating the utility of the CBCL for the purpose of psychosis risk screening is warranted. This measure possesses multiple advantages such as: 1) assessment of a wide range of social and behavioral problems; 2) screening for psychosis risk in the context of a general checklist with a widespread use in community and general healthcare settings; 3) reduction of the effects of mental health stigma in at-risk youth and their family members; 4) an inexpensive adjunctive approach that can result in the identification of individuals at the greatest risk for developing prodromal and psychotic symptoms in the future. In addition, the CBCL and other similar measures like the BASC-2 (which also shows promise as a psychosis risk screening instrument; Thompson et al., 2013), could serve as a first step in a multi-stage screening process that can make screening procedures more precise and reduce falsepositives in individuals who score high on psychosis-risk measures. Given the high rate of falsepositives in clinical high-risk individuals (also variably referred to as ‘psychosis risk syndrome,’ ‘ultra high-risk,’ or ‘prodromal’) and that the majority of those individuals do not go on to develop psychosis (Correll et al., 2010), a stage-wise screening process is a feasible approach to enhance broad-based community screening of individuals at risk for psychosis. Cost-effective general screening tools like the CBCL or BASC-2 could represent an initial stage in a two-step screening process. After an individual has been identified to be at risk given their profile, the second step would be administration of psychosis-specific instruments like the SIPS, the Prodromal Questionnaire – Brief Version (PQ-B; NEW REF - Loewy et al., 2011), Prime Screen – Revised (PS-R; Miller et al., 2004), or Youth Psychosis At Risk Questionnaire – Brief (YPARQ-B; Ord et al., 2004). This psychosis screening strategy would potentially streamline the process of early detection and treatment of youth at the highest possible risk for development of psychosis, reduce the unwanted effects of stigma, and potentially increase the precision of psychosis-risk screening. Also, recent findings indicate that the combination of parent and youth reports on the BASC-2 Atypicality scale significantly improves prediction of SIPS scores over either single-informant scale (Thompson et al., 2014). Therefore, further investigation of youth self-report in combination with parent-report in this context represents a potential future research direction.

There were some limitations in this study. The presence of participants taking psychotropic medications represented a methodological challenge (i.e., at-risk adolescents who manifest the most pronounced behavioral problems prior to baseline would be more likely to receive medications). While the present study was not intended to address questions about medication effects, the findings underscore that medication classes are differentially associated with behavior and that they should be examined in future research. Also, future research with larger samples may benefit from a regression approach, examining incremental improvements in prediction with the inclusion of additional measures. Another valuable approach might be to create positive (e.g., hallucination-like experiences, suspiciousness) and negative (e.g., social withdrawal) symptom domains from the respective CBCL items to determine, if parent-report of these specific constructs can enhance prediction. Future studies would also benefit from examination of other relevant variables in this context such as age and race. Finally, some participants in the study were receiving psychotherapy and other clinical care, which most likely has impact on CBCL ratings over time.

In summary, the present findings represent the first report in the literature of the CBCL being capable of differentiating at-risk adolescents in the general population as a function of their risk for subsequent psychosis development. The results indicate that future research examining the CBCL rating scales Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems and their utility to be used as broad-based screening tools in community and general pediatric samples is warranted. This will advance further the development of novel early intervention and prevention approaches in youth at risk for the development of psychosis.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2. CBCL Internalizing Problems scores by diagnostic group over time.

AR=at-risk, OPD=other personality disorders, NC=normal controls

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all youth participating in this research study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributors: Each of the contributors has made a substantial contribution to the research and the preparation of the manuscript: Diana I. Simeonova, Dipl.-Psych., Ph.D., Theresa Nguyen, B.A., and Elaine F. Walker, Ph.D.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amminger GP, Pape S, Rock D, Roberts SA, Ott SL, Squires-Wheeler E, et al. Relationship between childhood behavioral disturbance and later schizophrenia in the New York High-Risk Project. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(4):525–530. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballon JS, Kaur T, Marks II, Cadenhead KS. Social functioning in young people at risk for schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(2):179–192. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 2004;75(5):1523–1537. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon TD, Rosso IM, Bearden CE, Sanchez LE, Hadley T. A prospective cohort study of neurodevelopmental processes in the genesis and epigenesis of schizophrenia. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11(3):467–485. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt B, Obuchowski M, Schnur DB, O'Brien JD. Attention and clinical symptoms in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Q. 1997;68(4):343–359. doi: 10.1023/a:1025495030997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt B, Lencz T, Obuchowski M. The schizophrenia prodrome: treatment and high-risk perspectives. Schizophr Res. 2002;54(1-2):177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CU, Hauser M, Auther AM, Cornblatt BA. Research in people with psychosis risk syndrome: a review of the current evidence and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):390–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Ferdinand RF, van Lang ND, Bongers IL, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms from early childhood to late adolescence: gender differences and adult outcome. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(7):657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Done DJ, Crow TJ, Johnstone EC, Sacker A. Childhood antecedents of schizophrenia and affective illness: social adjustment at ages 7 and 11. BMJ. 1994;309(6956):699–703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6956.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. Neurobehavioral deficits in offspring of schizophrenic parents: liability indicators and predictors of illness. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97(1):65–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(200021)97:1<65::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 20) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gutt E, Petresco S, Krelling R, Busatto G, Bordin I, Lotufo-Neto F. Gender differences in aggressiveness in children and adolescents at risk for schizophrenia. Rev Bras Psychiatry. 2008;30:110–117. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462008000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans SL, Auerbach JG, Asarnow JR, Styr B, Marcus J. Social adjustment of adolescents at risk for schizophrenia: the Jerusalem Infant Development Study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(11):1406–1414. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone EC, Abukmeil SS, Byrne M, Clafferty R, Grant E, Hodges A, et al. Edinburgh high risk study - findings after four years: demographic, attainment and psychopathological issues. Schizophr Res. 2000;46(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Moe LC. First-episode schizophrenia: I. Early course parameters. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):241–256. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire - Brief Version (PQ-B) Schizophr Res. 2011;129:42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PM, Byrne M, Hodges A, Lawrie SM, Johnstone EC. Childhood behaviour, psychotic symptoms and psychosis onset in young people at high risk of schizophrenia: early findings from the Edinburgh High Risk Study. Psychol Med. 2002;32(1):173–179. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Somjee L, Markovich PJ, Stein K, et al. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):863–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, Cadenhead K, Cannon T, Ventura J, Woods SW. Prodromal assessment with the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes and the Scale for Prodromal Symptoms: predictive validity, interrrater reliability, and training to reliability. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:703–715. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TJ, Cicchetti D, Markovich PJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW. The SIPS screen: a brief self-report screen to detect the schizophrenia prodrome. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(Suppl. 1):78. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Tessner KD, Trotman HD, Esterberg M, Dhruv SH, Simeonova DI, et al. Movement abnormalities and the progression of prodromal symptomatology in adolescents at risk for psychotic disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:260–267. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Grimes K, Walker EF, Baum K. Developmental pathways to schizophrenia: behavioral subtypes. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104(4):558–566. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Walker EF. Neuromotor functioning in adolescents with schizotypal personality disorder: associations with symptoms and neurocognition. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(2):285–298. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME. Information processing and attentional functioning in the developmental course of schizophrenic disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(2):160–203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin SC, Mednick SA. Risk factors of psychosis: identifying vulnerable populations premorbidly. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22(2):223–240. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ord L, Myles-Worsley M, Blailes F, Ngiralmau H. Screening for prodromal adolescents in an isolated high-risk population. Schizophr Res. 2004;71(2-3):507–508. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV) American Psychiatric Press; Washington D.C: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children. second. AGS Publishing; Circle Pines, MN: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein ML, Mavrolefteros G, Turnbull A. Premorbid factors in relation to motor, memory, and executive functions deficits in adult schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;61(2-3):271–280. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(02)00312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonova DI, Attalla A, Trotman H, Esterberg M, Walker EF. Does a parentreport measure of behavioral problems enhance prediction of conversion to psychosis in clinical high-risk adolescents? Schizophr Res. 2011;130:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford MR, Jackson H, Mayo-Wilson E, Morrison AP, Kendall T. Early interventions to prevent psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346(f185):1–13. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox SI, Addington J, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, Perkins DO, et al. Premorbid functional development and conversion to psychosis in clinical high riskyouths. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(4 Pt 1):1171–86. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E, Kline E, Reeves G, Pitts SC, Schiffman J. Identifying youth at risk for psychosis using the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition. Schizophr Res. 2013;151:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E, Kline E, Reeves G, Pitts SC, Bussell K, Schiffman J. Using parent and youth reports from the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition to identify individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2014;154:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF, Downey G, Bergman A. The effects of parental psychopathology and maltreatment on child behavior: a test of the diathesis-stress model. Child Dev. 1989;60:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF, Weinstein J, Baum K. Antecedents of schizophrenia: moderating influences of age and biological sex. In: Hafner H, Gattaz W, editors. Search for the Causes of Schizophrenia. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1995. pp. 21–42. [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF, Logan C, Walder DJ. Indicators of neurodevelopmental abnormality in schizotypal personality disorder. Psychiatr Ann. 1999;29(3):132–136. [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF. Adolescent neurodevelopment and psychopathology. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2002;11:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Watt NF. Patterns of childhood social development in adult schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(2):160–165. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770260038003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, Phillips LJ, Kelly D, Dell'Olio M, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:964–971. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.