Abstract

The long-awaited crystal structure of Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA polymerase ε reveals a unique domain never before observed in family B DNA polymerases. This novel domain endows polymerase ε with a capacity for highly processive DNA synthesis.

Despite their opposite polarity, the two antiparallel strands of the DNA double helix are synthesized concomitantly as the replication fork translocates in a single direction. Given that the vast majority of DNA polymerases share a reaction mechanism that adds nucleotides to the 3′ terminus only, nature has devised a strategy of discontinuous synthesis in the 3′ to 5′ direction, whereby short RNA primers are extended and ligated to form the nascent lagging strand. It is therefore not surprising that evolution has selected for specialization in the DNA polymerases, which contribute their enzymatic activities specifically in leading and lagging strand synthesis. Three family B DNA polymerases (α, δ, and ε)1 comprise the eukaryotic replisome and the latter two bear the responsibility of synthesizing most of the DNA in dividing eukaryotic cells. In yeast DNA polymerase δ is believed to synthesize the lagging strand, while DNA polymerase ε extends the leading strand2. In this issue, Hogg et al. unveil the first crystal structure of DNA polymerase ε at 2.2 Å (ref. 3), providing the companion structure required for comparison to polymerase δ, for which structural information is already available for the catalytic domain4 and regulatory subunits5. Importantly, the new structural data explain why, unlike polymerase δ, polymerase ε does not rely on the PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) sliding clamp for its high processivity.

The first crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of polymerase δ from budding yeast was published in 2009, revealing the molecular basis of high fidelity by replicative eukaryotic DNA polymerases4. Polymerase δ tightly binds the minor groove of the DNA and juxtaposes a 3′→5′ proofreading exonuclease domain opposite the palm domain, where the catalytic aspartates coordinate divalent metal ions required for catalysis of polymerization6. Like many family B DNA polymerases, polymerase δ houses dual activities and is able to shuttle the DNA primer terminus approximately 40 Å between the polymerase and exonuclease active sites for degradation when a misinsertion is sensed due to abnormalities in the geometry of the DNA minor groove. This proofreading mechanism is key to the high fidelity of polymerases δ and ε, and mutations in their exonuclease domains are observed routinely in cancers7. DNA polymerase α contributes no proofreading activity to replicative DNA synthesis, but rather acts in complex with primase subunits to negotiate the altered geometry of the DNA/RNA-primed hybrid double helix and grow the primer with deoxyribonucleotides8. Polymerase δ then resolves the mismatches introduced by polymerase α at a later point in DNA synthesis9.

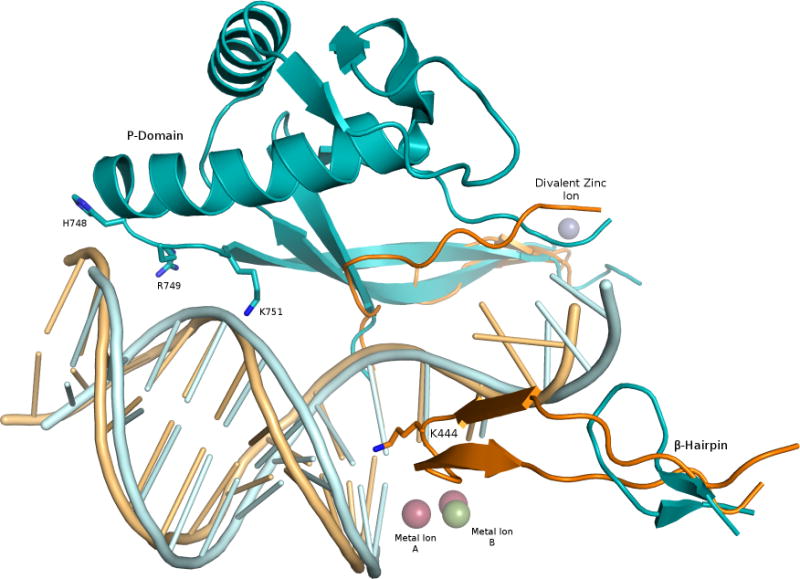

The current structure shows a ternary complex of the C-terminally truncated catalytic subunit of polymerase ε (residues 1–1229) not only revisits the conserved elements identified in other high fidelity family B polymerase structures, such as the deep intercalation of Lys967 in the DNA minor groove, which serves to check the geometry of the DNA, but also shows how these strategies of quality control are uniquely enhanced. Johansson and colleagues observed a novel domain in the catalytic subunit of polymerases ε poised to make additional contacts to the DNA that are not possible for polymerase δ, nor any of the other family B polymerases (Figure 1). Two unique insertions, residues 533–555 and 682–760, comprise this novel domain, which the authors named the processivity domain (P-domain), due to its ascribed role in maintaining polymerase ε’s tight hold on the DNA. Unlike polymerase δ, polymerase ε does not rely on the PCNA sliding clamp for its high processivity. The authors show that processivity can be abrogated by mutation to alanine of three protein residues in the P-domain (His748, Arg749, Lys751) that lie near the phosphate backbone approximately 10 base pairs, or one turn of the helix, away from the active site.

Figure 1.

Comparison of polymerase ε and polymerase δ structural domains. The vestigial β hairpin and P domain of polymerase ε (shown in cyan) are contrasted with the corresponding regions of polymerase δ (PDB 3IAY4; orange). The P domain is unique to polymerase ε, and its β hairpin is truncated compared to that of polymerase δ. Residues His748, Arg749 and Lys751 of polymerase ε are poised to contact the DNA backbone about 10 base pairs from the polymerase active site, marked by metal ions A and B. The divalent zinc ion (purple sphere) rests at the base of the P domain.

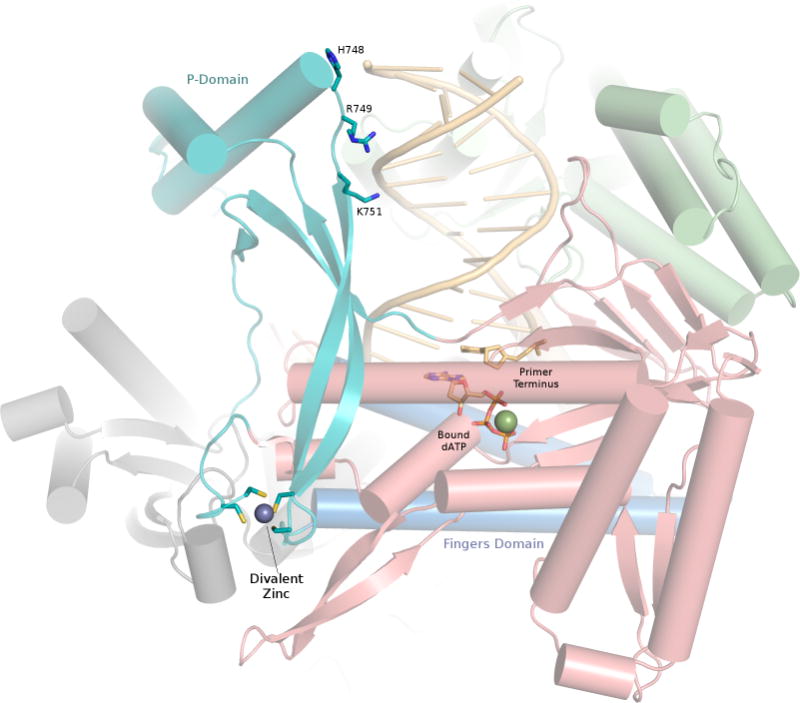

A recent paper from the Aggarwal laboratory reports the presence of an iron-sulfur (FeS) cluster (likely 4Fe-4S) within the catalytic core of yeast DNA polymerase ε, which is lost upon mutation of cysteines 665, 668, and 763 to serine, along with the brownish tint observed for the purified polymerase expressed in E. coli10. Please note that this FeS cluster is different from that found in the C-terminal domain of yeast B family polymerases, which involves cysteines 2164, 2167, 2179 and 2181 in S. cerevisiae polymerase ε11. Interestingly, the metal-binding residues in the catalytic core of the polymerase lie at the base of the large P-domain insert, where polymerase ε departs from the conventional fold of family B polymerases (Figure 2). The three cysteines, in addition to Cys677, are observed in the polymerase ε structure, but they are coordinating a single divalent zinc ion. Johansson and colleagues report that Cys667 and Cys763 are well defined, but Cys665 and Cys668 lie within a flexible loop. The loop spanning residues 669–675 was omitted from the model, presumably due to the disorder in this region of the crystallized protein. While partial order in this metal-binding motif may seem unlikely, there is precedence for flexibility in regions bearing a FeS cluster, as seen recently in the XPD helicase, for example12.

Figure 2.

Close-up view of the P domain and metal-binding region. Four cysteine residues coordinate the divalent zinc (purple sphere) at the base of the P domain (cyan). The P domain is well oriented to relay any loss of contacts to the DNA at residues His748, Arg749 and Lys751 to the fingers domain (blue), which is directly adjacent to the metal-binding site. Palm, thumb and N-terminal domains are shown in red, green and gray, respectively. The exonuclease domain is shown in the background, behind the DNA molecule. Bound ATP and DNA primer terminus shown as sticks.

The discrepancy as to whether this metal-binding site coordinates Zn2+ or 4Fe-4S will undoubtedly prompt speculation concerning its potential biological role. The primary P-domain insertion lies near the base of the fingers domain. The fingers domain in family B polymerases consists of two long parallel helical segments that pivot open and closed about a “hinge” region with each round of nucleotide incorporation. Several antimutator T4 gp43 variants have been identified with mutations in this hinge region, and this phenotype is likely due to destabilization of the closed replicating complex in favor of the open conformation, where switching the primer terminus to the exonuclease active site is facilitated13. Given the proximity of the metal binding site to this hinge (Figure 2), the site might function to modulate the predisposition of polymerase ε for exonuclease proofreading, depending on the nature or oxidation state of the bound metal ion.

The β hairpin structure in family B polymerases exists as an appendage of the exonuclease domain and is known to participate in active site switching14. Compared to other B family polymerases, and in particular polymerase δ, the β hairpin of polymerase ε appears atrophied (Figure 1). This clue might point to the potential of the P-domain to stall the polymerase for proofreading, thereby compensating or negating the need for a full-length β hairpin.

The replicative DNA polymerases serve critical roles in genome integrity and propagation, and structural data are invaluable in defining the molecular mechanisms that safeguard against mutations and cancer. The current structure of polymerase ε provides an exciting opportunity to examine the newly discovered P-domain, which will be the focus of future studies aiming to discern the subtleties of its structure-function relationship to proofreading and processivity. The conundrum of the metal binding site in the catalytic subunit of polymerase ε requires future interrogation, which could produce an interesting addition to the mounting evidence that mitochondria-derived cofactors, such as FeS clusters, play crucial roles in the metabolism and health of eukaryotic cells. With the structure of the catalytic subunit of polymerase ε accounted for, its regulatory subunits, Dpb2, Dpb3 and Dpb4 remain to be described. We will be eagerly awaiting the structure of the holoenzyme.

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported by US National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA052040

Footnotes

Competing financial interests:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Johansson E, Macneill SA. The eukaryotic replicative DNA polymerases take shape. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:339–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyabe I, Kunkel TA, Carr AM. The major roles of DNA polymerases epsilon and delta at the eukaryotic replication fork are evolutionarily conserved. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogg M, et al. Structural basis for processive synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase epsilon. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2014;21:49–55. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swan MK, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S, Aggarwal AK. Structural basis of high-fidelity DNA synthesis by yeast DNA polymerase delta. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:979–86. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranovskiy AG, et al. X-ray structure of the complex of regulatory subunits of human DNA polymerase delta. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3026–36. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.19.6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steitz TA. DNA polymerases: structural diversity and common mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17395–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Church DN, et al. DNA polymerase epsilon and delta exonuclease domain mutations in endometrial cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:2820–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perera RL, et al. Mechanism for priming DNA synthesis by yeast DNA Polymerase alpha. Elife. 2013;2:e00482. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavlov YI, et al. Evidence that errors made by DNA polymerase alpha are corrected by DNA polymerase delta. Curr Biol. 2006;16:202–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jain R, et al. An Iron-Sulfur Cluster in the Polymerase Domain of Yeast DNA Polymerase epsilon. J Mol Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Netz DJ, et al. Eukaryotic DNA polymerases require an iron-sulfur cluster for the formation of active complexes. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:125–32. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolski SC, Kuper J, Kisker C. The XPD helicase: XPanDing archaeal XPD structures to get a grip on human DNA repair. Biol Chem. 2010;391:761–5. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li V, Hogg M, Reha-Krantz LJ. Identification of a new motif in family B DNA polymerases by mutational analyses of the bacteriophage t4 DNA polymerase. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogg M, Aller P, Konigsberg W, Wallace SS, Doublié S. Structural and biochemical investigation of the role in proofreading of a beta hairpin loop found in the exonuclease domain of a replicative DNA polymerase of the B family. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1432–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605675200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]