Abstract

Physicochemical properties constitute a key factor for the success of a drug candidate. Whereas many strategies to improve the physicochemical properties of small heterocycle-type leads exist, complex hydrocarbon skeletons are more challenging to derivatize due to the absence of functional groups. A variety of C–H oxidation methods have been explored on the betulin skeleton to improve the solubility of this very bioactive, yet poorly water soluble, natural product. Capitalizing on the innate reactivity of the molecule, as well as the few molecular handles present on the core, allowed for oxidations at different positions across the pentacyclic structure. Enzymatic oxidations afforded several orthogonal oxidations to chemical methods. Solubility measurements showed an enhancement for many of the synthesized compounds.

Keywords: C-H activation, Medicinal chemistry, Oxidation, Radical reactions, Terpenoids

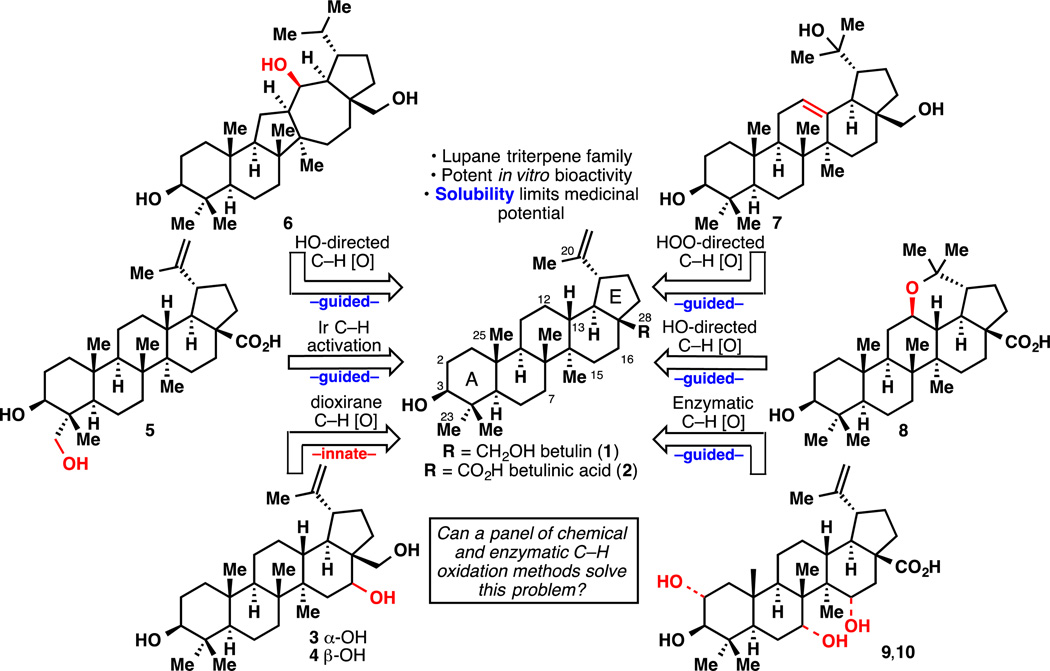

The rates of attrition for small-molecule drug candidates remain excessively high at any stage of drug development despite a continuously improving understanding of drug-target interactions, drug distribution and metabolism.[1] Consequently, the cost of discovering and developing a drug in 2010 was estimated to be approximately $1.8 billion.[2] Historically, some of the main reasons behind drug failure are the lack of efficacy, toxicity and poor pharmacokinetic properties or bioavailability. Unsatisfactory physicochemical properties have specifically emerged as a common source of drug failure.[3] A subtle balance between lipophilicity and polarity is therefore required to ensure a viable future to a drug candidate. In the case of heterocyclic leads, this balance can be achieved by substituting some positions of the heteroarenes with hydrogen bond donors and/or acceptors, as well as various fluorinated motifs. When the drug candidate is a natural product derivative, however, the quest for an ideal solubility and cell permeability is often hampered by the few positions that can be accessed. This is especially true in the case of lowly oxidized terpenes, where only a few carbons of the skeleton can be modified using conventional chemical means. Our laboratory has been developing various aliphatic C–H functionalization methods and strategies for a biomimetic ‘oxidase phase’ in natural product synthesis.[4] It was in this context that a collaboration was forged with Bristol-Myers Squibb to probe the applicability of these studies in drug discovery and more precisely the improvement of drug physicochemical properties. The lupane natural products betulin (1) and betulinic acid (2) are ideal substrates to explore this concept due to their promising in vitro bioactivity coupled with their extreme insolubility thus limiting their medicinal potential. This Communication outlines a strategy for improving the solubility of this promising natural product class using both chemical and enzymatic means.[5] This combination of orthogonal techniques has lead to a dramatic improvement in solubility of the lupane core (Figure 1) thus setting the stage to realize their full medicinal potential.

Figure 1.

Diversification of the Lupane Core via C–H Oxidation.

Betulin (1) and betulinic acid (2) are two natural pentacyclic triterpenes isolated from the bark of the birch tree that only differ by the oxidation at C28 (Figure 1).[6] Betulin is more abundant than its carboxylic acid counterpart but is generally less bioactive.[7] Several methods have been developed to convert 1 into 2.[8] Betulinic acid displays many intriguing pharmacological properties such as anti-inflammatory, anticancer and anti-HIV, the latter two being the most promising for pharmaceutical applications.[7,9] However, the low solubility of 2 in H2O constitutes a serious limitation for its use as a therapeutic, since it would make formulation for oral delivery difficult.[7] To render 1 and 2 more soluble in aqueous media, the lipophilic carbon skeleton must be decorated with heteroatoms. However, oxidation of the lupane core presents many challenges, due to the very few functional groups present on the skeleton. Prior art has mainly focused on oxidation of the A ring that already possesses a C3 alcohol as a handle[10] and modification of the isopropenyl group via allylic C–H oxidation or direct transformation of the alkene.[10c,11] On the other hand, known oxidations of the B, C and D rings are scarce and have mostly utilized the C28 alcohol as a directing group.[12] To the best of our knowledge, only one group has reported a non-directed oxidation of lupanes leading to functionalization of C ring.[13] However, their conditions (CrO3 in boiling acetic acid) afforded many compounds in yields all below 3%.[13a,b] Finally, it is of note that several C–H bonds can be biochemically oxidized by feeding betulinic acid (2) to microorganisms.[7a]

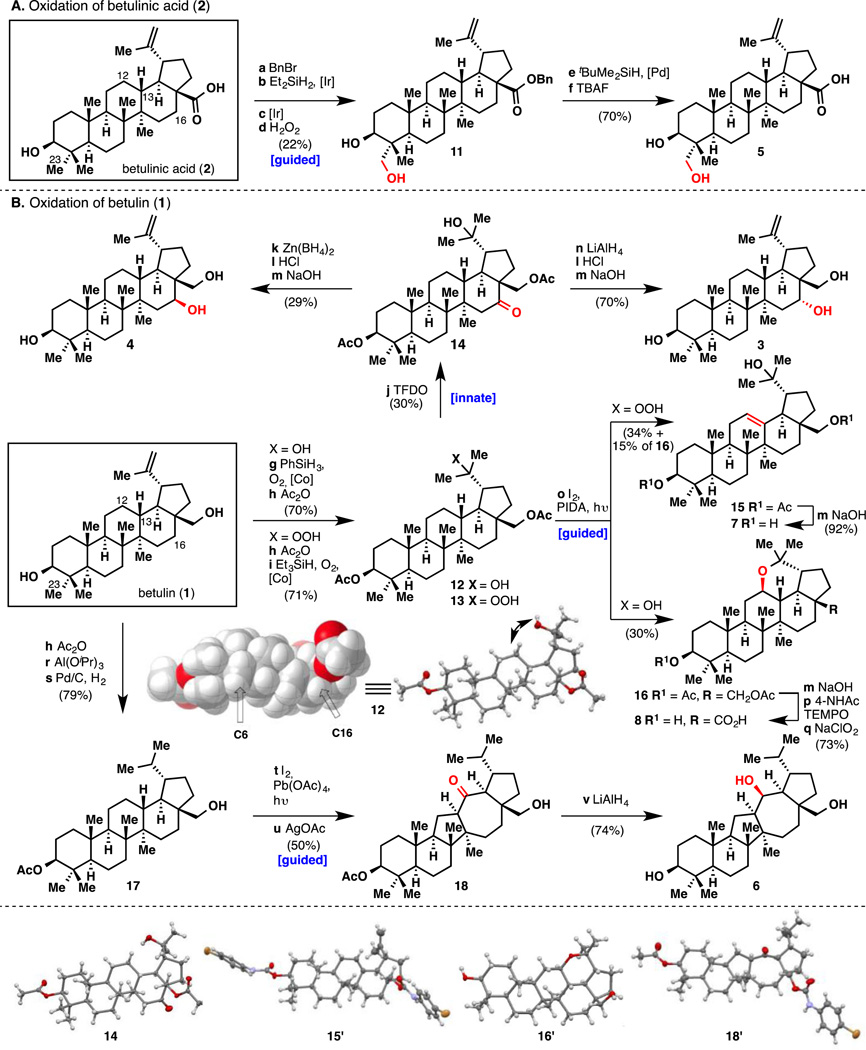

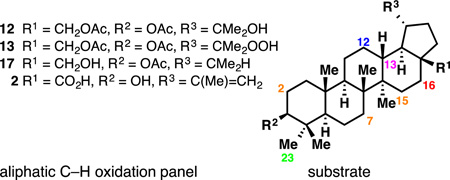

With that precedent in mind, and by analogy to studies conducted on eudesmane terpenes,[4a] two different strategies were applied to oxidize various unactivated aliphatic C–H bonds of 1 or 2. Thus, non-directed (innate) C–H oxidation would capitalize on the default reactivity of the 48 C–H bonds of betulin (1) [46 for betulinic acid (2)], whereas directed (guided) C–H oxidation would employ the hydroxyl groups at C3, C28 or C20 (arising from hydration of the alkene).[14] To achieve innate C–H oxidation, the two hydroxyl groups and the alkene required protection, since they are the most prone to oxidation. Carreira’s hydration conditions[15] followed by diacetylation afforded substrate 12 in good yield (Figure 2). X-Ray crystallographic analysis of 12 suggested that it would be oxidized at a methylene position since all the methine positions are fairly hindered. The electronic character of all the C–H bonds was evaluated through 13C NMR studies.[4a, 16] Every carbon peak was unambiguously assigned using 13C–13C INADEQUATE NMR and the chemical shift trend was determined as follows (see Supplementary Information for actual values):

δC6 < δC11 < δC2 < δC15 ≈ δ21 ≈ δ12 ≈ δC16 < δC22 ≈ δC7 < δC1 << δC28

Figure 2. Divergent Synthesis of Oxidized Compounds from A) Betulinic acid B) Betulin.

Reagents and conditions: (a) BnBr, K2CO3, 60 °C, 3.5 h, 92%; (b) 1 mol% [Ir(cod)OMe]2, Et2SiH2, r.t., 12 h; (c) 2 mol% [Ir(cod)OMe]2, 5 mol% Me4Phen, norbornene, 120 °C, 36 h; (d) H2O2, KHCO3, 50 °C, 12 h, 24% (over 3 steps); (e) 50 mol% Pd(OAc)2, Et3N, tBuMe2SiH, 60 °C, 2.5 h; (f) TBAF, r.t., 1.5 h, 70% (over 2 steps); (g) Sodium-bis-[N-salicylidene-2-amino-isobutyrato]-cobaltate(III) (20), PhSiH3, O2, r.t., 10 h; (h) Ac2O, pyr, r.t., 99% (70% for 12 over 2 steps); (i) 20, Et3SiH, O2, r.t., 14 h, 71%; (j) TFDO, 0 °C, 2 h, 30%; (k) Zn(BH4)2, r.t., 1 h, 80% (1:1 d.r.); (l) HCl, 0 °C (− 41°C for 4); (m) NaOH, r.t., 12 h, 72% for 4 (over 2 steps) (70% for 3 (over 3 steps), 92% for 7); (n) LiAlH4, – 95 °C, 1 h; (o) I2, PIDA, hυ, r.t., 15 min, 30% of 16 from 14; 34% of 15 and 15% of 16 from 13; (p) 40 mol% 4-NHAcTEMPO, PIDA, r.t. 3 h; (q) NaClO2, NaH2PO4•H2O, 2-methyl-2-butene, r.t., 2.5 h, 73% (over 3 steps); (r) Al(OiPr)3, iPrOH, 100 °C, 1.5 h; (s) Pd/C, H2, r.t., 12 h, 79% (over 3 steps); (t) I2, Pb(OAc)4, hυ, r.t., 15 min; (u) AgOAc, r.t., 20 h, 50% (over 2 steps); (v) LiAlH4, 0 °C, 1 h, 74%.

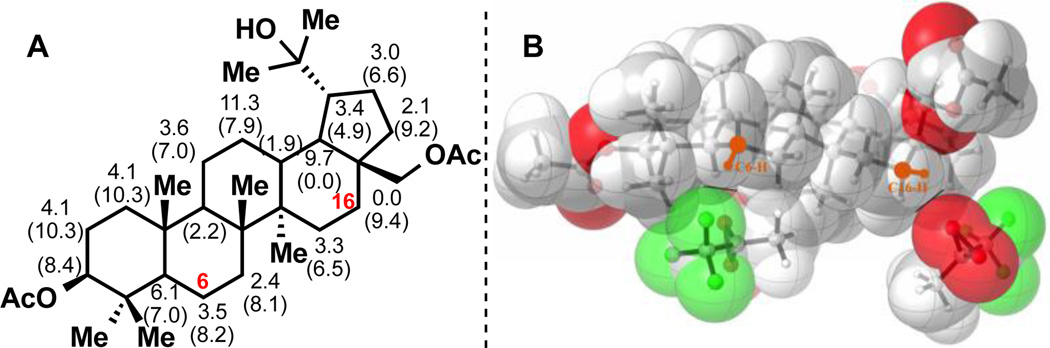

Based on this analysis, positions C6 to C16 are the most electron-rich methylenes, and thus most likely to be oxidized. Dozens of oxidants were screened, but most of them resulted in no reaction or an inextricable mixture of products, including the reported CrO3 conditions.[13a,b] Fortunately, it was found that methyl(trifluoromethyl)dioxirane (TFDO) afforded the C16 ketone product 14 in 30% yield as major product, as confirmed by X-ray crystallography. No minor products were isolated in quantities sufficient for characterization, but it is of note that none of these products contained a ketone motif. While TFDO has been previously used to selectively oxidize a sesquiterpene skeleton in the total synthesis of eudesmantetraol,[4a] this reaction constitutes the first example of selective methylene oxidation in the context of a complex triterpene substrate. The striking selectivity for C16 cannot be explained solely by electronic factors since 6 carbons are more electron-rich based on 13C NMR.

Calculations using the UB3LYP functional were performed to determine the origins of this surprising selectivity. Activation energies for attack at the ring carbon hydrogen bonds by dimethyldioxirane (DMDO) were computed (Figure 3A). Based on our previous computational studies, C–H oxidation using DMDO or TFDO involves a concerted reaction, initiated by CH abstraction followed by a barrierless oxygen rebound from a radical pair.[17] DMDO is less reactive than TFDO and more selective.[17] The calculated ΔH‡ for the oxidation of equatorial C16–H is found to be 3.5 kcal/mol lower than that of C6–H and is considerably lower that activation energies computed for all other positions (see Figure 3A). This difference drops to 1.6 kcal/mol with TFDO (see Supporting Information (SI)). The abstraction of the C16 equatorial hydrogen is consistent with our previous finding that equatorial C–H bonds are more reactive due to both the strain release effect[17,18] and higher steric accessibilities. Thus, Figure 3B shows an oxygen of TFDO just touching the surface of the hydrogen at C16 and C6. The former occurs with no clashing of van der Waals surfaces, while approach at C6–H involves significant steric repulsions of the dimethyl at C4 of betulin and the CF3 groups of TFDO. These interactions are confirmed in the transition state geometries given in Figure S13 (SI). The stability of radicals formed by hydrogen abstraction at all positions were also calculated (see Figure 3A). Remarkably, the C–H oxidation process is extremely selective, and hydrogen abstraction occurs only at C16. This is in spite of the fact that the diradical transition state has appreciable diradical character at C16 in 12, where a radical is intrinsically of low stability. Finally, calculations on the analog of 12 where the C17 CH2OAc group is replaced by a methyl group (see SI) showed that the C–H abstraction barrier at C16 is lowered by 1.6 kcal/mol by removing the inductively electron-withdrawing ester, thus ruling out a potential neighboring effect from the acetate group.

Figure 3. Analysis of Site Selectivities on 12 for TFDO.

A) Relative activation enthalpies for equatorial C–H abstraction by DMDO (ΔΔH‡) and relative stabilities of the free radicals (ΔΔE, in parentheses) (kcal/mol). B) Juxtaposition of space-filling models of TFDO approaching C6–H and C16–H in 12, to indicate the steric effects disfavoring C–H abstraction from C6–H. The relative orientations of TFDO and 12 were determined from the transition state geometries shown in Figure S13 (SI).

Derivative 14 was then reduced to the axial alcohol using LiAlH4 and 3 was obtained after elimination and saponification. Zn(BH4)2 reduction of 14 afforded a 1:1 mixture of diastereomers that could be separated and equatorial alcohol 4 was obtained with a similar sequence as for 3. The structure of 4 has been attributed to the natural product heliantriol B2 in the literature. However, our NMR data did not perfectly match the reported data of this natural product,[19] which suggests a potential misassignment of heliantriol B2 since the structure of 4 was confirmed by X-ray crystallography. However, the lack of details in the isolation report might explain the observed discrepancies.

Functionalization of the A ring was then pursued using the C3 alcohol as a directing group. After benzylation of betulinic acid (2), Hartwig’s elegant 1,3-diol methodology was applied.[20] Silylation of the C3 alcohol, followed by C–H silylation at C23 and Tamao–Fleming oxidation afforded 11 in 24% yield. A two-step debenzylation delivered the natural product C23-hydroxybetulinic acid (5). 5 has been previously synthesized from betulinic acid using a Baldwin-type C–H oxidation.[21] In that study, transformation of the alcohol into an oxime directing group, C–H oxidation with stoichiometric palladium and then two-step regeneration of the alcohol was required. Hartwig’s conditions avoided these four steps of functional group manipulations and do not necessitate protection of the C20–C21 alkene.

Functionalization of the C ring was achieved via the intermediacy of a hydroxyl radical at C20. Indeed, an oxygen radical could be generated using Suárez’s conditions on substrate 12,[22] resulting in C–H abstraction, iodine trap and displacement leading to the formation of tetrahydropyran product 16 in 30% yield. While this type of transformation generally leads to tetrahydrofuran formation, the specific geometry of the system results in 1,6-hydrogen abstraction rather than 1,5. Compound 16 has been previously synthesized in a related transformation, but using lead tetraacetate in refluxing benzene for several hours.[23] Derivative 16 was then transformed into carboxylic acid 8, by removal of the acetate groups and a selective two-step oxidation of the primary alcohol. The tetrahydropyran ring in 16 proved to be very stable, and no hydrolysis conditions could be developed. Consequently, the venerable Barton nitrite ester reaction was considered to install a ketone at C12 in place of the cyclic ether.[24] Unfortunately, formation of the nitrite ester of the tertiary alcohol with NOCl in pyridine was ineffective, probably due to steric hindrance. The benzylic C–H oxidation directed by a peroxyl radical reported by both Kropf and Čeković then caught our attention.[25] To examine this directed oxidation, peroxide 13 was synthesized in two steps in very similar fashion as 12. Using triethylsilane instead of phenylsilane and removing the reductive work-up allowed for the preparation of the desired peroxide. This substrate was then subjected to the same Suárez conditions and two products were isolated. The minor product was the previously isolated tetrahydropyran 16 (15% yield), whereas the major product was the desaturated compound 15 (34% yield). This compound corresponds to Čeković’s findings, but interestingly, their exact conditions applied on 13 only afforded tetrahydropyran 16. However, adding Cu(OAc)2 to our reaction conditions enabled a slight improvement of the alkene yield, consistent with a mechanism involving hydrogen abstraction, followed by radical oxidation and proton elimination.[25f] Hydrolysis of the acetate groups delivered 7 which could serve as a platform for further modifications of the C ring.

A few reports have described oxidation of C13 using a hydroxyl radical at C28. The substrate for this transformation is hydrogenated monoacetate compound 17 and different authors reported the formation of the corresponding tetrahydrofuran product, albeit generally in low yields, after thermal or photoactivation of the hydroxyl radical. In our hands, however, this product could not be isolated despite many conditions that were tried. Instead, the formation of an iodinated product was observed when using lead tetraacetate and iodine under a sunlamp.[26] This product could not be purified and was subsequently treated with silver acetate in acetone.[22a] This two-step procedure initiated a rearrangement of the carbon skeleton providing 18 in 50% yield (X-ray analysis), presumably via a 1,2-shift of the C13–C14 bond. From a medicinal chemist’s point of view, this unexpected transformation allows for the exploration of the bioactivity and physicochemical properties of a new family of compounds possessing an intriguing 6,6,5,7,5 pentacyclic structure. Finally, reduction of 18 with an excess of LiAlH4 afforded triol 6.

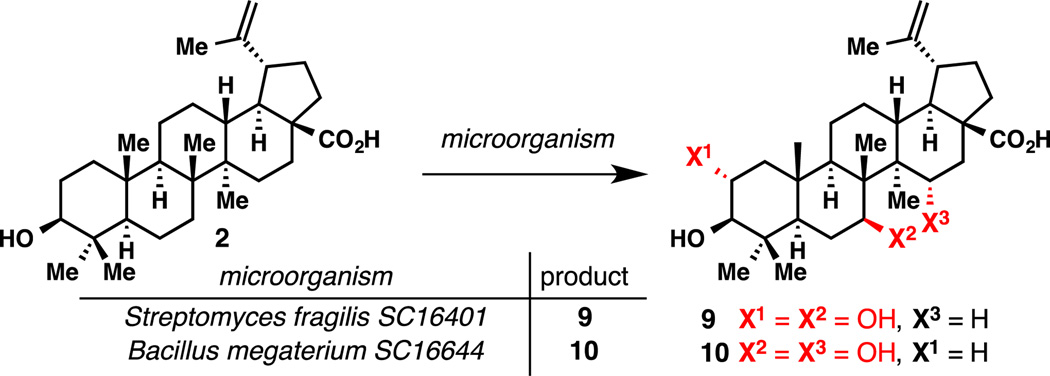

In parallel to these chemical studies, BMS screened several microorganisms in order to oxidize betulinic acid (2) as shown in Figure 4. It was found that Streptomyces fragilis tranformed 2 into diol 9, whereas Bacillus megaterium afforded diol 10 instead.[27]

Figure 4.

Microbial Oxidations of Betulinic Acid (2).

The panel of aliphatic C–H oxidations that were developed on the lupane core are summarized in Table 1. Alcohol 12 can serve both for the directed oxidation of C12 and non-directed oxidation of C16 with TFDO (entry 1, 2 and 4). No other oxidants were found to enable the same reaction (entry 5–9).[28] From hydroperoxide 13 arose alkene 15 and ether 16, two compounds oxidized at C12 (entry 1). Alcohol 17 is the precursor of the C13 oxidation followed by skeletal rearrangement (entry 2) and benzylated 2 is that of C23 oxidation (entry 10). Interestingly, all the developed enzymatic C–H oxidations are orthogonal to the chemical C–H oxidations (entry 11 and 12), which illustrates the complementarity of these two approaches.

Table 1.

Summary of Aliphatic C−H Oxidation Panel Used on the Lupane Skeleton.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | conditions | 12 | 13 | 17 | 2 |

| 1 | PIDA, I2, hυ | C12 | C12 | decomp. | – |

| 2 | Pb(OAc)4, I2, hυ | C12 | trace | C13 | – |

| 3 | NOCl, pyr | N.R. | – | – | – |

| 4 | TFDO | C16 | – | – | – |

| 5 | DMDO | N.R. | – | – | – |

| 6 | KMnO4 | N.R. | – | – | – |

| 7 | CrO3, nBu4NIO4[28a] | decomp. | – | – | – |

| 8 | RuCl3•×H2O, KBrO3[28b] | N.R. | – | – | – |

| 9 | Crabtree’s Ir catalyst[28c] | N.R. | – | – | – |

| 10 | Hartwig’s 1,3-diol | – | – | – | C23a |

| 11 | Streptomyces fragilis | – | – | – | C2/C7 |

| 12 | Bacillus megaterium | – | – | – | C7/C15 |

R1 = CO2Bn.

The solubility of these new oxidized compounds was tested in simulated intestinal fluids and compared to reference compounds (betulin (1) or betulinic acid (2)) possessing the same oxidation state at C28 (Table 2). The solubility was measured in both fasted state (assay 1) and fed state (assay 2).[29] The solubility of 3 and 7 in assay 1 is over 100-fold higher than that of 1, while nearly identical in assay 2. The solubility of 8 is 17-fold higher in assay 2 than that of 2, albeit somewhat lower in assay 1. Consequently, adding one hydroxyl group to 1 and 2 drastically improved their solubility. This work clearly demonstrates the unpredictable nature of skeletal oxidation on solubility since 4 has almost identical solubility to 1 despite having one more alcohol and diols 9 and 10 are less soluble than 2 (only a slight improvement seen in assay 2). Finally, the solubility of the rearranged product 6 is the lowest of all the family.

Table 2.

Relative Solubility Enhancement of the Oxidized Compounds.

| Entry | Substrate | R1 | Relative Solubility Enhancement: Assay 1 (FaSSIF)a |

Relative Solubility Enhancement: Assay 2 (FeSSIF)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | CH2OH | 274× | no change |

| 2 | 4 | CH2OH | 8.00× | 0.077× |

| 3 | 7 | CH2OH | 121× | 0.357× |

| 4 | 6 | CH2OH | no change | 0.077× |

| 5 | 5 | CO2H | 0.056×c | 0.115×c |

| 6 | 8 | CO2H | 0.112×c | 17.4×c |

| 7 | 9 | CO2H | 0.019×c | 3.38×c |

| 8 | 10 | CO2H | 0.002×c | 0.462×c |

Solubility ratio substrate/betulin (1) in fasted state simulated intestinal fluid.

Solubility ratio substrate/betulin (1) in fed state simulated intestinal fluid.

Solubility ratio substrate/betulinic acid (2). R1 refers to the position shown in the structure of Table 1 (C17).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published systematic study using both chemical and enzymatic methods for aliphatic C–H oxidation with the goal of improving physical properties. It is our hope that this study will help to alleviate some of the “empiricism” in the process of screening oxidants and that the combination of spectroscopy, crystallography, and computation along with a systematic C–H oxidation panel will serve to accelerate future efforts. C–H oxidation clearly merits consideration by medicinal chemists confronted with the challenge of an exciting chemotype whose further development is hampered by extreme insolubility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the NIH (GM097444-03) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (postdoctoral fellowship to G.J.). We are grateful to Prof. A. Rheingold and Dr. C.E. Moore (UCSD) for X-ray crystallographic analysis, Dr. D.-H. Huang, Dr. L. Pasternack (TSRI), Dr. Frank A. Rinaldi, Dr. Xiaohua Huang and Jacob Swidorski (BMS) for assistance with NMR spectroscopy and Gerry Everlof for solubility measurements.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Quentin Michaudel, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037.

Guillaume Journot, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037.

Alicia Regueiro-Ren, Discovery Chemistry, Bristol-Myers Squibb, 5 Research Parkway, Wallingford, Connecticut 06492.

Animesh Goswami, Chemical Development, Bristol-Myers Squibb, One Squibb Drive, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903.

Zhiwei Guo, Chemical Development, Bristol-Myers Squibb, One Squibb Drive, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903.

Thomas P. Tully, Chemical Development, Bristol-Myers Squibb, One Squibb Drive, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903

Lufeng Zou, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569.

Raghunath O. Ramabhadran, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569

Kendall N. Houk, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1569

Phil S. Baran, Email: pbaran@scripps.edu, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037.

References

- 1.(a) Kola I, Landis J. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery. 2004;3:711. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, Economides C, Rosentha J. Nature Biotechnology. 2014;32:40. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paul SM, Mytelka DS, Dunwiddie CT, Persinger CC, Munos BH, Lindborg SR, Schacht AL. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2010;9:203. doi: 10.1038/nrd3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meanwell NA. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011;24:1420. doi: 10.1021/tx200211v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Chen K, Baran PS. Nature. 2009;459:824. doi: 10.1038/nature08043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ishihara Y, Baran PS. Synlett. 2010:1733. [Google Scholar]; (c) Renata H, Zhou Q, Baran PS. Science. 2013;339:59. doi: 10.1126/science.1230631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jørgensen L, McKerrall SJ, Kuttruff CA, Ungeheuer F, Felding J, Baran PS. Science. 2013;341:878. doi: 10.1126/science.1241606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A dual chemical/enzymatic C–H oxidation strategy on pharmaceutical substrates was previously published, see: Genovino J, Lütz S, Sames D, Touré BB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:12346. doi: 10.1021/ja405471h. For a purely chemical approach to both predict and block metabolic hot spots using C–H functionalization, see: O’Hara F, Burns AC, Collins MR, Dalvie D, Ornelas MA, Vaz ADN, Fujiwara Y, Baran PS. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:1616. doi: 10.1021/jm4017976.

- 6.(a) Löwitz JT. Crell’s Chem. Ann. 1788;1:312. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bruckner V, Kovacs J, Koczka I. J. Chem. Soc., Abstr. 1948:948. doi: 10.1039/jr9480000948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hayek EWH, Jordis U, Moche W, Sauter F. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:2229. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For reviews, see Cichewicz RH, Kouzi SA. Med. Res. Rev. 2003;24:90. doi: 10.1002/med.10053. Alakurtti S, Mäkelä T, Koskimies S, Yli-Kauhaluoma J. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006;29:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2006.04.006.

- 8.(a) Ruzicka L, Lamberton AH, Christie EW. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1938;21:1706. [Google Scholar]; (b) Robertson A, Soliman G, Owen EC. J. Chem. Soc. 1939:1267. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kim DSHL, Chen Z, Nguyen VT, Pezzuto JM, Qiu S, Lu Z. Synth. Commun. 1997;27:1607. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For reviews, see Pisha E, Chai H, Lee IS, Chagwedera TE, Farnsworth NR, Cordell GA, Beecher CWW, Fong HHS, Kinghorn AD, Brown DM, Wani MC, Wall ME, Hieken TJ, Das Gupta TK, Pezzuto JM. Nat. Med. 1995;1:1046. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1046. De Clercq E. Med. Res. Rev. 2000;20:323. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200009)20:5<323::aid-med1>3.0.co;2-a.

- 10.(a) Deng Y, Snyder JK. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:2864. doi: 10.1021/jo010929h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mukherjee R, Jaggi M, Siddiqui MJA, Srivastava SK, Rajendran P, Vardhan A, Burman AC. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:4087. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Santos RC, Salvador JAR, Marín S, Cascante M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:6241. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Suokas E, Hase T. Acta Chem. Scand. B. 1975;29:139. [Google Scholar]; (b) Suokas E, Hase T. Acta Chem. Scand. B. 1977;31:182. [Google Scholar]; (c) Dutta G, Bose SN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:5807. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sun IC, Wang HK, Kashiwada Y, Shen JK, Cosentino LM, Chen CH, Yang LM, Lee KH. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4648. doi: 10.1021/jm980391g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Šarek J, Klinot J, Džubák P, Klinotová E, Nosková V, Křeček V, Kořínková G, Thomson JO, Janošt'áková A, Wang S, Parsons S, Fischer PM, Zhelev NZ, Hajdúch M. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:5402. doi: 10.1021/jm020854p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Alakurtti S, Heiska T, Kiriazis A, Sacerdoti-Sierra N, Jaffe CL, Yli-Kauhaluoma J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:1573. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Allison JM, Lawie W, McLean J, Taylor GR. J. Chem. Soc. 1961:3353. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vystrčil A, Protiva J. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1974;39:1382. [Google Scholar]; (c) Nag SK, Bose SN. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:2855. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sejbal J, Klinot J, Buděšínský M, Protiva J. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1991;56:2936. Sejbal J, Klinot J, Buděšínský M, Protiva J. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1997;62:1905. Oxidation of C19 using dry ozonation or peracids in ca. 10% yield have been disclosed as well: Suokas E, Hase T. Acta Chem. Scand. B. 1978;32:623. Tori M, Matsuda R, Asakawa Y. Chem. Lett. 1985:167. Sejbal J, Klinot J, Vystrčil A. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1987;52:487.

- 14.Brückl T, Baxter RD, Ishihara Y, Baran PS. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012;45:826. doi: 10.1021/ar200194b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waser J, Gaspar B, Nambu H, Carreira EM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11693. doi: 10.1021/ja062355+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For the first demonstration that 13C shifts could be used to assist in the prediction of C–H oxidation, see ref. 4a. See also: Bigi MA, Liu P, Zou L, Houk KN, White MC. Synlett. 2012;23:2768. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1317708.

- 17.Zou L, Paton RS, Eschenmoser A, Newhouse TR, Baran PS, Houk KN. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:4037. doi: 10.1021/jo400350v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen K, Eschenmoser A, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9705. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pyrek JS. Polish J. Chem. 1979;53:2465. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Simmons EM, Hartwig JF. Nature. 2012;483:70. doi: 10.1038/nature10785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li B, Driess M, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:6586. doi: 10.1021/ja5026479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun F, Zhu P, Yao H, Wu X, Xu J. J. Chem. Res. 2012:254. [Google Scholar]

- 22.(a) Concepción JI, Francisco CG, Hernández R, Salazar JA, Suárez E. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:1953. [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM, Shen HC, Surivet J-P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12565. doi: 10.1021/ja048084p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pouzar V, Protiva J, Lisá E, Klinotová E, Vystrčil A. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 1975;40:3046. [Google Scholar]

- 24.(a) Barton DHR, Beaton JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:2640. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barton DHR, Beaton JM, Geller LE, Pechet MM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1961;83:4076. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Kropf H, von Wallis H. Synthesis. 1981:237. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kropf H, von Wallis H. Synthesis. 1983:633. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kropf H, von Wallis H. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1983:610. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kropf H, von Wallis H, Bartnick L. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1983:624. [Google Scholar]; (e) Čeković Ž, Green MM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:3000. [Google Scholar]; (f) Čeković Ž, Dimitrijević Lj, Djokić G, Srnić T. Tetrahedron. 1979;35:2021. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalvoda J, Heusler K. Synthesis. 1971:601. [Google Scholar]

- 27.A manuscript disclosing the full biotransformation studies is in preparation

- 28.(a) Lee S, Fuchs PL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:13978. doi: 10.1021/ja026734o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McNeill E, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10202. doi: 10.1021/ja1046999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Graeupner J, Brewster TP, Blakemore JD, Schley ND, Thomsen JM, Brudvig GW, Hazari N, Crabtree RH. Organometallics. 2012;31:7158. doi: 10.1021/om300696t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.For the use of physiologically relevant media like FeSSIF or FaSSIF for solubility measurements of drug-like substrates, see: Fagerberg JH, Tsinman O, Sun N, Tsinman K, Avdeef A, Bergström CAS. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2010;7:1419. doi: 10.1021/mp100049m.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.