The Bylaws of the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) charge the Research and Graduate Affairs committee (RGAC) with the development of the Association’s research, graduate education and scholarship agenda.1 To this end, the RGAC met in Crystal City, VA on October 28 and 29, 2013, to begin deliberating on the charges for 2013-14. The committee subsequently conducted frequent conference calls and electronic communications throughout the year to prepare this report.

President Peggy Piascik outlined the following charges to the RGAC:

1. Assess the landscape of current work in the area of community-engaged scholarship (CES) in the academy including its depth and breadth.

2. Define, develop metrics, and suggest appropriate recognition for community-engaged scholarship.

3. Identify and promote funding opportunities for pharmacy in CES.

4. Identify barriers and training opportunities for members of the Academy in community–engaged research.

The RGAC chose to adopt a definition whereby CES is recognized as teaching, discovery, integration, application and engagement that involves the faculty member in a mutually beneficial partnership with the community and has the following characteristics: clear goals, adequate preparation, appropriate methods, significant results, effective presentation, reflective critique, rigor and peer-review.2

Introduction

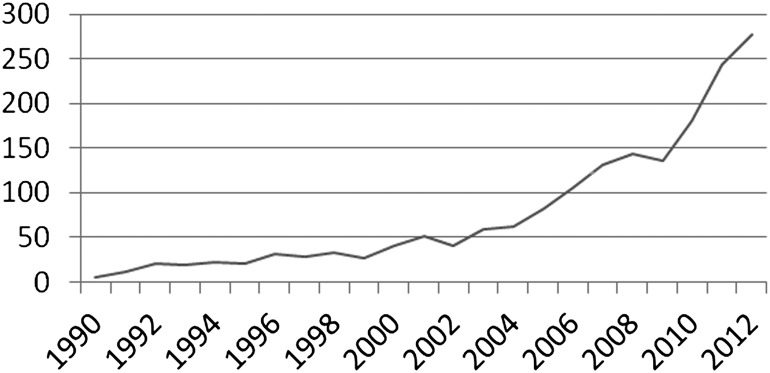

The interest and literature associated with CES has increased significantly in the past ten years (Figure 1). Since 2000, there has been a five-fold increase in the number of published papers indexed in PubMed under the search term, “Community-Engaged Research.” This increase in scholarly papers parallels the interest by professional organizations,2 the academic health care community,3,4 and our own academy5,6 in addressing this unmet need. First identified by Ernest Boyer in 1996, CES was endorsed by the 2004-05 AACP Argus Commission.6 This report issued a number of recommendations to increase community engagement by pharmacy schools, through stimulating funding, increasing scholarly activity, and improving recognition and rewards to faculty involved in these endeavors.

Figure 1.

Number of Published Papers under the heading “Community Engaged Research” in Pubmed, 1990-2012

Unfortunately, progress has lagged behind the unrealized promise.4 Academic departments and universities have been slow to accept CES.8,9 Few tenure and promotion committees have formal written guidelines for what constitutes CES or routinely accept this form of scholarship as part of academic promotion or continuance.10-12 Without clear incentives and recognition for this type of collaborative work, faculty have been reluctant to engage in an activity that may not be recognized by their peers. These problems, among others, have resulted in a delay in accepting this expanded definition of scholarship by the academy.

With an understanding of this “gap” between stated goals in the area of CES and the slow pace of widespread acceptance in the academy, the RGAC has developed the following vision statement for academic pharmacy:

VISION: The academy has the responsibility to improve health at the community’s interface with the practice of pharmacy through scholarship.

With this background, our report will outline the importance of CES, describe a model for advancing this topic for academic pharmacy and provide the academy with recommended steps, strategies, and resources necessary to move toward a culture of CES.

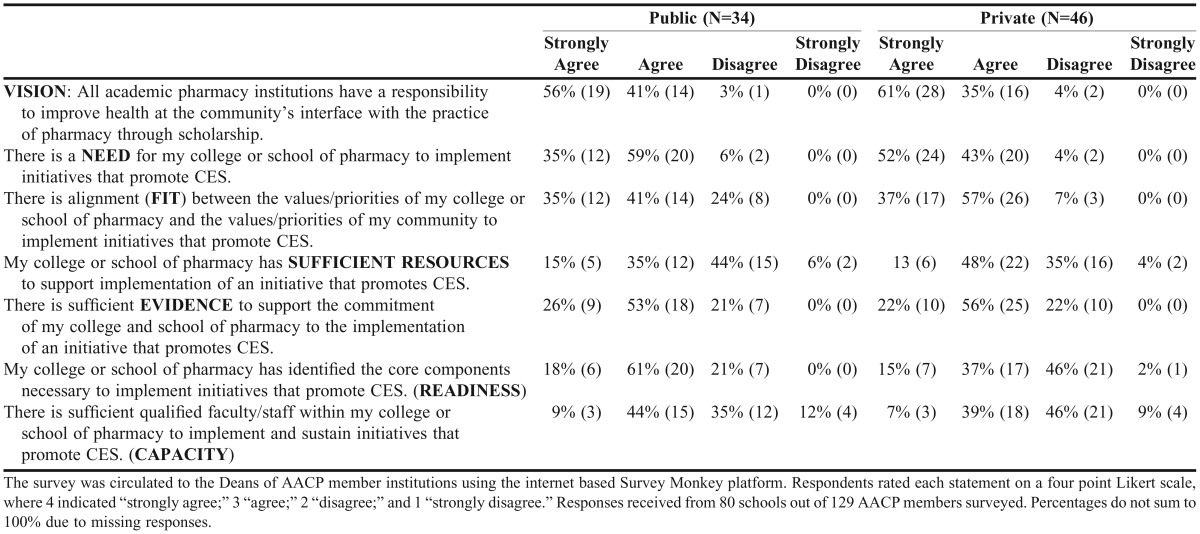

Importance of the Scholarship of Engagement to Pharmacy

The 2004-05 AACP Argus Commission Report addressed the call for greater civic responsibility on the part of institutions of higher education. The Commission examined the opportunity for scholarship that improves health at the community’s interface with the practice of pharmacy. The 2013-14 Research and Graduate Affairs and Advocacy Committees surveyed the CEO Deans of AACP member institutions to assess what extent their institution is engaged with the community. They reported on the alignment between the mission of their institution and community engagement, and rated the challenges and strategies needed to support CES including the capacity, readiness and availability of resources to support the scholarship of community engagement. Survey results related to CES (the focus of the RGAC) are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

CEO Dean’s perceptions on institutional support and challenges for the scholarship of community engagement.

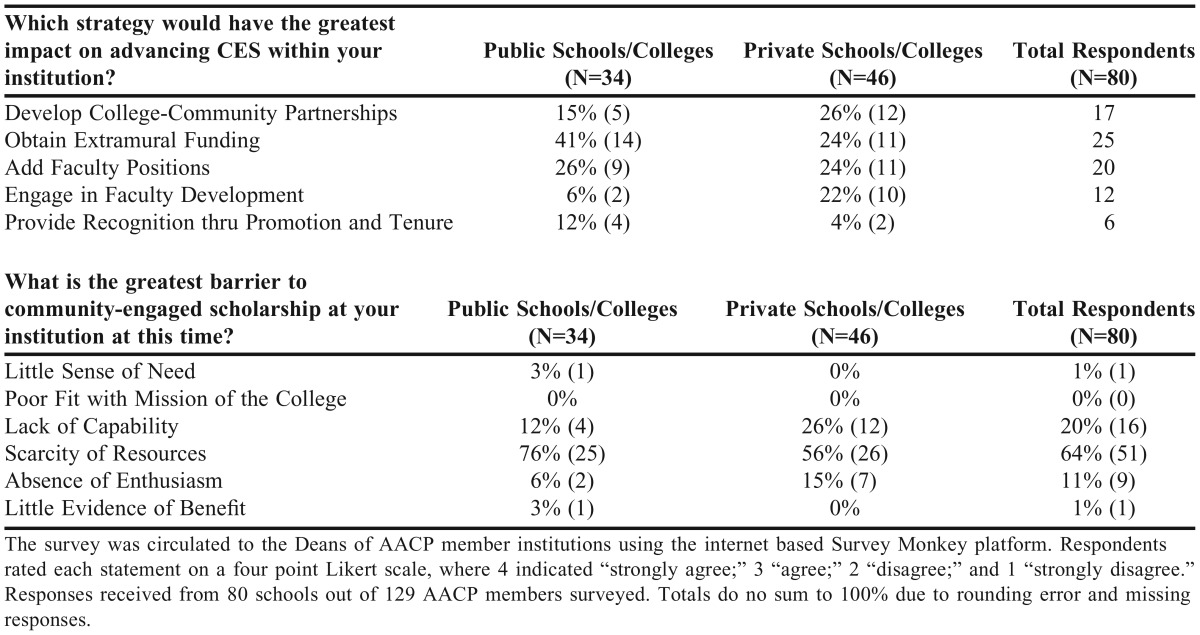

Table 2.

CEO Dean perceptions of most impactful strategies and barriers to advancing CES.

Over 95% of the 80 survey respondents agreed that schools and colleges of pharmacy have a responsibility to improve health at the community’s interface with the practice of pharmacy through scholarship (Table 1). While there was near universal agreement about institutional responsibility, fewer Deans agreed that alignment of values and priorities exist between their institution and their community. Interestingly, the greatest level of disagreement on this alignment was present with public institutions (24% disagreement), the group that one would anticipate would be most focused on engagement considering the expectations associated with state funding. It is unclear whether this level of disagreement is referencing lack of alignment with institutional priorities, lack of priority on the part of the practice community, or both.

In other areas of support and challenges, there were few differences in the responses from private (N=46) and public institutions (N=34) overall (Table 1). Public institutions tended to be slightly more concerned with their fit and resources for the scholarship of community engagement while the private institutions expressed a bit more concern about their readiness and capacity than with their fit and availability of resources. The presence of adequate capacity and availability of resources to support community-engaged scholarship were areas in which respondents showed the least level of agreement. Both public and private institutions were split with respect to their perception of having the expertise present within their faculty and the resources necessary to implement initiatives that would produce scholarship from community engaged work.

The respondents were distributed across cities of various population sizes. Public institutions were much more likely to be affiliated with an academic medical center than the private schools, 68% versus 20% respectively. Not surprisingly, schools within an academic medical center expressed greater opportunity to secure extramural funding for community-engaged scholarly work.

The survey also asked respondents to highlight the greatest opportunities and barriers to advancing the efforts of community-engaged scholarship at their institutions (Table 2). Not surprisingly, both groups ranked scarcity of resources as the greatest barrier, although private schools were also somewhat concerned about the lack of capacity and an absence of enthusiasm as barriers.

Published literature on challenges to CES has been limited, although some documented challenges are quite formidable.3,4,11 There is a lack of common definition and general understanding of CES that would clearly distinguish between service learning and clinical teaching components. Policies and practices differ across institutions with some fundamental concerns about liability, research integrity, conflict of interest,13 as well as a traditional dependence upon clinical revenue for research support. It will require changes in both practice policies and institutional culture to overcome these barriers.3

It is widely recognized that scholarly initiatives that engage with partners in communities require time for faculty to create, maintain and sustain these partnerships.12 Institutions themselves must invest in infrastructure to ensure that faculty have the training, skills, and resources to support the development of CES. Specific recommendations for the necessary structure and process include:

• Integrate CES into the organization’s strategic plans with support from institutional investments in the community;

• Involve administrative arrangements and committees to facilitate community input and enhance community engagement;

• Train faculty, staff, and students to engage in CES through service, experiential learning, and graduate research courses;

• Provide research support for faculty and staff including practice based research networks, research coordinators, communications through websites and blogs, and streamlined processes for research approval;

• Support mentoring and consultation for faculty, staff, and students;

• Ensure an ongoing, systematic evaluation of community engagement activities and achievements; and

• Acknowledge and support CES through promotion and tenure processes, intramural funding and public recognition.14

Specific to academic pharmacy, there is evidence that successful projects are based upon existing relationships with community partners including pharmacies, primary care medical homes and accountable care organizations. Scholarly work requires the engagement of existing partners in grant development with some projects initiated by the community partners. These sustained partnerships often build synergy and trust which facilitates data sharing15 and an entrée to the university research infrastructure.16 It is clear, without a pre-existing relationship, network, collaboration, and unwavering institutional support, initiating and achieving successful community engagement research and scholarship cannot be envisioned. Experienced pharmacy researchers in the United Kingdom recognize the importance of knowledge and infrastructure built through ongoing relationships. Scholarly endeavors must take account of the context and complexity of practice, its capacity to accommodate interventions, and its constant evolution. Successful collaborations depend upon understanding the dynamics of power and motivating interests of partners at the organizational and individual levels. Conversely, practitioners generally are not aware of the challenges associated with funding, nor meeting the expectations and demands of the academic institution. Factors that facilitate CES include the efficient use of technical staff, consideration of the logistics and compatibility of organizational priorities.17

Goodwill is a necessary but not sufficient condition for CES. There must be a personal commitment to developing individual relationships with bi-directional exchange of information that leads to shared leadership and respect for divergent interests. Flexibility is key to successful scholars who also need great determination, long-term vision and leadership skills.17

Comparing the results of the CEO Dean survey with the discourse from the literature on CES, the RGAC has noted a “chicken vs. egg” scenario. CEO Deans clearly indicated that issues around funding/resources were the greatest barrier to success to community-engaged scholarship and highlighted extramural funding as the factor most likely to stimulate CES. However, the literature speaks specifically to the need to establish foundational assets before community-engaged work can become a consistent scholarly enterprise within an institution. Thus prioritizing internal time and resources for CES is critical to building relationships, expertise and momentum such that external funders can recognize the capacity necessary in an organization to successfully support this form of scholarship. Building a foundation for success in CES is not unlike what is required to build an institution’s success in the scholarship of discovery. For an institution to move into a new area of scientific research such as drug discovery, pharmacogenomics, etc., strategic investments are required, which often include formalizing commitment via a strategic plan, hiring faculty or building existing faculty expertise, and committing internal resources such as space and faculty effort allocation.

A Framework for Advancing Community-Engaged Scholarship in Academic Pharmacy

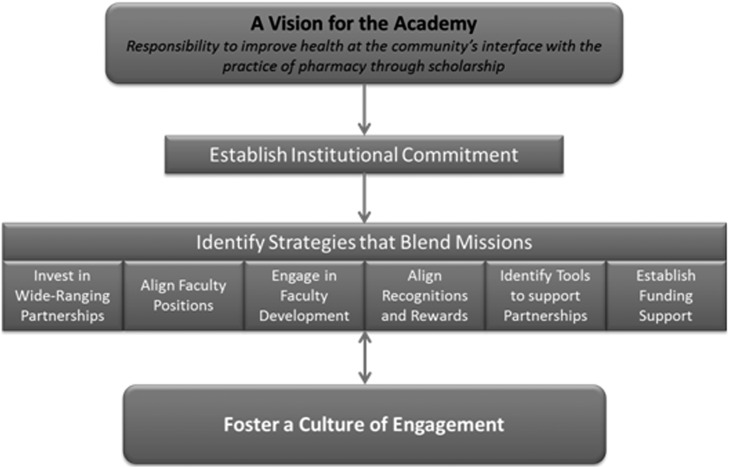

As the RGAC reviewed previous work addressing CES, identified barriers to its implementation in schools of pharmacy, and recognized models of success, a framework for the adoption and growth of community-engaged scholarship in the academy started to emerge. This framework (Figure 2) includes several elements, described here.

Figure 2.

Framework for Advancement of Community-Engaged Scholarship

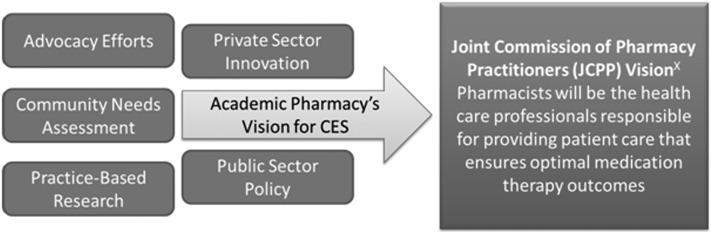

Vision for the Academy: A vision statement describes what an organization or group wants to be or what it aspires to be. It is an idealized, long-term view that concentrates on the future. Considering the RGAC charges and the desire for meaningful change, the group determined that establishing a vision for the future of CES in academic pharmacy could galvanize AACP member schools’ commitment to growth in this area. The vision established by the RGAC has its underpinnings in the current reality that pharmacists remain underutilized in health care. This concept is also inherent in the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) Vision for Pharmacy practice which states that patients achieve optimal health and medication outcomes with pharmacists as essential and accountable providers within patient-centered, team-based healthcare.

While momentum is building in several areas, achievement of the JCPP vision will require years of practice development, research and advocacy. The RGAC envisions that academic pharmacy will embrace the responsibility to improve health through CES as one critical strategy that will bring us closer to achieving JCPP’s vision for the profession (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Community-Engaged Scholarship Contributing to the JCPP Vision for Pharmacy

In order to achieve this vision for the academy, the RGAC also considered what a vision would look like at the level of individual institutions. Achievement of the vision for the academy would include our member institutions demonstrating evidence of institutional structure and capacity; success in obtaining extramural funding from federal agencies and private foundations; systematic collection of data and analyses for peer-review publications; sustainable programs that can be adopted by other communities; formal recognition of quality and value of the established research, including its team and investigators; and evidence that the research program is making progress and is sustainable.

Institutional Commitment: As described in the introduction to this report, a number of factors have prevented CES from gaining significant traction as an area of scholarly pursuit. If the academy chooses to adopt the vision promoted by this report, it will be incumbent on the leadership of schools and colleges of pharmacy to establish formal and visible institutional commitment to CES. Once a school’s leadership team has internally made a commitment to invest in CES and publicly communicated a vision for how the work will be developed, organized and supported, strategies to achieve the vision can be pursued.

Identify Strategies that Blend Missions: It is unlikely that a commitment to CES in an institution will be established via a separate and distinct set of initiatives. Rather, a focus on CES has a greater chance of emerging through a concerted effort to align this work with existing priorities of the institution. For example, strong, collaborative partnerships with communities or community-based organizations are essential to the success of CES. However, these relationships may best emerge from partnerships that also focus on curricular needs (e.g. experiential education) or service opportunities (e.g., alumni affairs, extra-curricular community service). An investment in wide-ranging partnerships that cut across multiple missions is viewed as a strategy to capitalize on opportunities for CES. Institutional leaders should look to organizations that have had success in creating these types of partnerships in order to identify tools and strategies from which they can build on.

Hiring new faculty is typically an opportunity to address both the teaching and research missions of an institution. Aligning faculty positions with an expectation for CES, possibly in shared relationships with community-based partners, begins to create a critical mass of faculty with a specific interest in this type of scholarship. However, it is unlikely that momentum can be achieved through hiring practices alone, thus creating opportunities for faculty development is necessary to prepare current faculty who wish to align their scholarly pursuits with community-engaged scholarship.

Like most new endeavors, an initial investment is necessary to kick start the development of ideas, relationships and action. While there is certainly extramural funding available for research that is aligned with the principles of CES, the ability to attract this funding may be incumbent on establishing some initial infrastructure and a modest track record of success. Establishing funding support to trigger new CES pursuits within an institution is a strategy that may bridge to grants or other forms of meaningful investment from external groups. Additionally, aligning recognition and rewards programs that may already be in place in the organization to fully embrace CES activities is critical to conveying to faculty that these scholarly endeavors are valued to the same degree as more long-established research activities. In particular, there is a need to ensure that community-engaged scholarship is recognized in university or school-level tenure and promotion criteria.

Culture of Engagement: Once institutional commitment is established and effective strategies to support faculty contributions to CES are in place, a school can begin to build a “culture of engagement” that will influence the leadership agenda of the school, enhance existing relationships with external partners and encourage faculty to view CES as a valued area for scholarly efforts. Through a culture of engagement, the institution can meaningfully improve health through scholarly efforts that engage both practice communities and the patients they serve.

Resources to Support Moving to a Culture of Engagement

Engagement in a community often requires human and financial resources. The following describes some general principles for securing those resources, and some suggestions about possible sources of funding and general support.

Partnerships: An important long-term strategy is to build relationships with community organizations with which academic investigators may jointly apply for grants. Such collaborations may include healthcare-providing institutions or other educational institutions. Other partnerships may include community philanthropic foundations or foundations associated with healthcare providers (physician groups, hospitals, clinics, etc.) or payers (insurers, etc.), corporate foundations, employers (with interests in maintaining the health of their employees and customers), alumni endowments, and patient advocacy groups.

While large statewide or national organizations may have more resources than smaller groups, local or regional foundations where investigators can develop relationships may be more likely to provide support than larger organizations. Furthermore, small organization grants are often adequate for supporting pilot projects and conducting feasibility studies.

Another national organization, Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH; https://ccph.memberclicks.net/) is a nonprofit membership organization that promotes health equity and social justice through partnerships between communities and academic institutions. CCPH’s archived website (http://depts.washington.edu/ccph/index.html; no longer updated) has a wide variety of resources, including publications, discipline-specific service-learning syllabi, and links to many websites. CCPH also publishes a toolkit for those interested in developing community-campus partnerships. 2

Campus Compact is a national higher education association dedicated to campus-based civic engagement. Among other things, Campus Compact “helps campuses forge effective community partnerships, and provides resources and training for faculty seeking to integrate civic and community-based learning into the curriculum.” The Campus Compact website has useful information, including links to resources for faculty from many colleges and universities, including tenure and promotion guidelines that take community engagement activities into consideration (http://www.compact.org/resources-for-faculty/).

Faculty Alignment and Development: Investigators who have not previously engaged with partners in the community may need to develop new skills in preparation for establishing and developing partnerships. It is often best to consult with a colleague that has done similar work, to learn about bridge-building skills and the essential elements of a collaborative philosophy.

It may also be helpful to seek a mentor that has initiated and developed partnerships and is willing to share the knowledge, understanding and wisdom that comes from such experience.

Faculty members interested in engaging in a community-based research project must have a solid understanding of research methods. A clinical academician may be an expert in his/her field, but may wish to carry out research – e.g., about educational outcomes – requiring different expertise. In such a case, it is often best to identify a colleague with the appropriate expertise, such as a statistician, to serve as a co-investigator or consultant.

In order to fund a project, it may be necessary to secure a grant or some other source of financial support. If the investigator is not experienced in grant-writing, his/her institution may offer assistance in this area, or external assistance may be available.

The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) provides information about CES including a rubric for planning and conducting research, and disseminating the results of studies, as well as general principles for engagement. (See http://www.pcori.org/assets/2014/02/PCORI-Patient-and-Family-Engagement-Rubric.pdf.)

As faculty members become more engaged in their local communities, including involvement in community-engaged scholarship, opportunities may arise for graduate students to participate in such endeavors. Some graduate students may choose to do their dissertation-related research in collaboration with community partners. Such work will begin to train the next generation of community-engaged scholars.

Beyond specific skills and strategies, various interests, attitudes and approaches are beneficial for the community-engaged practitioner and scholar. A desire to reach outside the institution, to connect with the local community and to engage that community – even though such engagement is often more complicated than other types of activity and scholarship – is a strong motivator. As with any type of scholarship, an interest in inquiry – exploring new areas, and asking critical questions – is important; and a reflective approach to one’s work is essential. Finally, because community-engaged scholarship is in many cases novel, a person who pursues this path must be innovative.

Because community-engaged scholarship is a relatively new area, there are opportunities and needs for new leaders in this field. For those who are interested, a step beyond being a practitioner and scholar could involve accepting an academic leadership position, such as associate dean or vice president of community engagement.

Recognition and Rewards: Various authors have written about how CES is viewed when it comes to promotion and tenure (P&T). Steckler and Dodds10 described the expansion of P&T guidelines to include community engagement at a public health school. Hofmeyer et al.8 made recommendations about how the scholarship of integration and the scholarship of application (Boyer’s categories7) can be weighed in P&T considerations. Marrero et al.11 described the relationship between community-engaged research and P&T at three CTSA-winning universities, and Nokes et al.12 described faculty perceptions of this relationship.

The above-mentioned CCPH toolkit2 contains helpful information about creating a promotion portfolio when a faculty member’s accomplishments include community engagement and associated scholarship (Unit 2 and Appendix A).

Tools to Support Partnerships: When entering into a partnership with a community-based organization, particularly when a goal of the partnership is to engage in research, a number of foundational issues must be addressed. If humans are to be the subject of the research, prior approval of an Institutional Review Board (IRB) must be secured. While most academicians are familiar with IRBs, community partners may need to be introduced to IRB procedures. In some cases, when a partner is a healthcare organization or another academic institution, multiple IRBs may need to review study protocols.

To ensure that potential liability and funding issues have been addressed, it may be necessary to execute a Memorandum of Understanding or a Business Association Agreement between and among the partners. This will likely involve legal representatives of the institutions, and time must be allotted for the necessary consultations and document preparation.

Academicians often intend to publish the findings of their research, and many organizations are interested in publicizing the work they are doing and/or the results of their research. Because of this, it is important to develop a publication/public relations plan at the beginning of any partnership, so that all parties understand each other’s expectations and plans.

If anyone anticipates that certain intellectual property may result from the partnership – such as patents or proprietary information – an Intellectual Property Protection plan needs to be established, with the agreement of all parties.

Funding Support: Organizations may periodically issue Requests for Proposals (RFPs) to institutions that they might be interested in funding, but it is often more advantageous to actively seek out potential funding sources and to try to “sell” innovative ideas, rather than waiting to receive a RFP. Though this approach may lead to a number of dead-ends, funders may view the active seekers as more pro-active, focused and vigorous organizations.

The Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA; https://www.ctsacentral.org/) program, supported by the National Institutes of Health, also supports a wide variety of medical research institutions throughout the U.S.

CONCLUSION

CES is an opportunity for schools of pharmacy to build community relationships, expertise and momentum such that external funders can recognize the capacity to support this form of scholarship within an organization. Schools must build a culture of engagement by prioritizing faculty time, formalizing and widely integrating the commitment of the institution, and allocating resources to support the growth and development of CES efforts. There are numerous opportunities for schools to utilize tools, resources, and strategies developed by national organizations and associations and engage with leaders and mentors in CES. Fully embracing community-engaged scholarship activities is critical to demonstrating that these scholarly endeavors are valued to the same degree as more traditional research activities.

AACP’s RGAC has developed this report to provide an overview of the current work in CES, acknowledge challenges to integrating CES, outline opportunities to promote the adoption of CES within the academy, and to develop recommendations for consideration by AACP. The six specific recommendations are outlined below.

Recommendations of the Committee

Recommendation 1. Council of Deans should use the Advocacy and Research and Graduate Affairs Committees’ Deans’ survey results and invite experts to initiate a dialogue and determine what directions schools should take to incorporate community-engaged scholarship across the academy.

Recommendation 2. AACP and Schools of Pharmacy should highlight the difference between community-engagement and community-engaged scholarship. Schools and colleges should evaluate and take their current level of community-engagement to the next level involving community-engaged research and scholarship.

Recommendation 3. AACP should organize discussion groups or training workshops for faculty. AACP should also encourage leadership development, networking, and collaboration across institutions and communities.

Recommendation 4. AACP should organize a special taskforce or special interest group to outline potential graduate courses or certificate programs that will prepare graduate students and postgraduates to pursue community-engaged research.

Recommendation 5. AACP should identify appropriate funding agencies and advocate for more funding opportunities to support community-engaged research.

Recommendation 6. AACP should establish guidance to colleges and schools regarding promotion and tenure guidelines in order to codify the recognition and reward of community-based work that benefits communities and advances the institution’s mission.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bylaws for the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, Inc. House of Delegates. http://www.aacp.org/governance/Documents/AACP%20Bylaws.pdf.

- 2. Commission on Community-Engaged Scholarship in the Health Professions. Linking Scholarship and Communities: Report of the Commission on Community-Engaged Scholarship in the Health Professions. Seattle: Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, 2005. https://depts.washington.edu/ccph/pdf_files/Commission%20Report%20FINAL.pdf.

- 3.Calleson DC, Jordan C, Seifer SD. Community-engaged scholarship: Is faculty work in communities a true academic enterprise? Acad Med. 2005;80:317–21. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kulynych J, Heffernan KG. Community research Partnerships. Underappreciated challenges, unrealized opportunities. JAMA. 2013;309:555–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.108937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nemire RE, Brazeau GA. Making community-engaged scholarship a priority. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73:Article 67. doi: 10.5688/aj730467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith RE, Kerr RA, Nahata MN, et al. Engaging Communities: Academic pharmacy addressing unmet public health needs. Report of the 2004-05 Argus commission. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69:Article S22. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer E. The scholarship of engagement. J Publ Serv Outreach. 1996;1:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofmeyer A, Newton M, Scott C. Valuing the scholarship of integration and the scholarship of application in the academy for health sciences scholars: Recommended methods. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2007:5. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-5-5. doi:10.1186/1478-4505-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meurer LN, Diehr S. Community-engaged scholarship: Meeting scholarly project requirements while advancing community health. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:385–6. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00164.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steckler A, Dodds J. Changing promotion and tenure guidelines to include practice: One public health school’s experience. J Publ Health Manage Pract. 1998;4:114–9. doi: 10.1097/00124784-199807000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marrero DG, Hardwick EJ, Staten LK, Savaiano DA, Odell JD, Comer KF, Saha C. Promotion and tenure for community-engaged research: an examination of promotion and tenure support for community-engaged research at three universities collaborating through a clinical and translational science award. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6:204–8. doi: 10.1111/cts.12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nokes KM, Nelson DA, McDonald MA, Hacker K, Gosse J, Sanford B, Opel S. Faculty perceptions of how community-engaged research is valued in tenure, promotion, and retention decisions. Clin Transl Sci. 2013;6:259–66. doi: 10.1111/cts.12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mullins CD, Abduhlhalim AM, Lavallee DC. Continuous patient engagement in comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2012;307:1587–1588. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szilagyi PG, Shone LP, Dozier AM, Newton GL, Green T, Bennett NM. Evaluating community engagement in an academic medical center. Acad Med. 2014;89:585–595. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000190. doi:10.1097/ACM 0000000000000190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eder M, Carter-Edwaesa L, Hurd TC, Rumala BB, Wallerstein N. A logic model for community engagement within the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium: Can we measure what we model? Acad Med. 2013;10:1430–1436. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829b54ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rickles NM, Schnur ES, Adams AJ, Russo NB. Forming strong collaboration among academic researchers, pharmacies and integrated delivery systems. Am J Pharm Ed. 2013;77(10):Article 227. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7710227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maher JH, Lowe JB, Hughes R, Anderson C. Understanding community pharmacy intervention practice: Lessons from intervention researchers. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2013.09.002. doi:10.101/j.sapharm.2013.09.002.[epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]