A novel cytochrome P450 monooxygenase is involved in multiple-herbicide detoxification and could be useful in herbicide development and molecular breeding in crops.

Abstract

Target-site and non-target-site herbicide tolerance are caused by the prevention of herbicide binding to the target enzyme and the reduction to a nonlethal dose of herbicide reaching the target enzyme, respectively. There is little information on the molecular mechanisms involved in non-target-site herbicide tolerance, although it poses the greater threat in the evolution of herbicide-resistant weeds and could potentially be useful for the production of herbicide-tolerant crops because it is often involved in tolerance to multiherbicides. Bispyribac sodium (BS) is an herbicide that inhibits the activity of acetolactate synthase. Rice (Oryza sativa) of the indica variety show BS tolerance, while japonica rice varieties are BS sensitive. Map-based cloning and complementation tests revealed that a novel cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, CYP72A31, is involved in BS tolerance. Interestingly, BS tolerance was correlated with CYP72A31 messenger RNA levels in transgenic plants of rice and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). Moreover, Arabidopsis overexpressing CYP72A31 showed tolerance to bensulfuron-methyl (BSM), which belongs to a different class of acetolactate synthase-inhibiting herbicides, suggesting that CYP72A31 can metabolize BS and BSM to a compound with reduced phytotoxicity. On the other hand, we showed that the cytochrome P450 monooxygenase CYP81A6, which has been reported to confer BSM tolerance, is barely involved, if at all, in BS tolerance, suggesting that the CYP72A31 enzyme has different herbicide specificities compared with CYP81A6. Thus, the CYP72A31 gene is a potentially useful genetic resource in the fields of weed control, herbicide development, and molecular breeding in a broad range of crop species.

The mechanism of herbicide tolerance can be classified roughly into two groups: target-site and non-target-site herbicide tolerance (Powles and Yu, 2010). Target-site herbicide tolerance is caused by the prevention of herbicide binding to the target enzyme, caused by point mutations occurring in the latter. It is relatively easy to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of target-site herbicide tolerance, because it is regulated mostly by a single gene encoding a target enzyme harboring point mutations. On the other hand, non-target-site herbicide tolerance is caused by reduction to a nonlethal dose of herbicide reaching the target enzyme, caused by mechanisms such as activation of herbicide detoxification, decrease of herbicide penetration, and herbicide compartmentation in plant cells (Yuan et al., 2007). Among these mechanisms, the oxidization of herbicides by endogenous cytochrome P450 monooxygenase is thought to be a major pathway in plants (Werck-Reichhart et al., 2000; Siminszky, 2006; Powles and Yu, 2010). From the point of view of weed control, non-target-site herbicide tolerance is a greater threat to crop production and in the evolution of herbicide-resistant weeds, because it is often involved in resistance to multiherbicides that inhibit different target proteins, including never-used and potential plant growth regulators (Yuan et al., 2007; Powles and Yu, 2010). Conversely, it is expected that multiherbicide-tolerant crops could be produced easily by the application of non-target-site herbicide tolerance. Moreover, information gained from study of the molecular mechanisms of non-target-site herbicide tolerance can be applied to the research and development of novel herbicides and plant growth regulators.

Acetolactate synthase (ALS; also known as acetohydroxy acid synthase) plays a key role in the biosynthesis of branched-chain amino acids such as Val, Leu, and Ile in many organisms. ALS is the primary target site for at least four classes of herbicides: sulfonylurea, imidazolinone, pyrimidinyl carboxylates, and triazolopyrimidine herbicides (Shimizu et al., 2002, 2005). These herbicides can inhibit ALS activity, resulting in plant death caused by a deficiency of branched-chain amino acids. ALS-inhibiting herbicides control many weed species in addition to exhibiting high selectivity in major crops and low toxicity to mammals, which lack the branched-chain amino acid biosynthetic pathway. However, various mutations in ALS that confer ALS-inhibiting herbicide tolerance have been found in many weeds (Shimizu et al., 2005; Powles and Yu, 2010). Similar mutations in ALS have also been reported in crops (Shimizu et al., 2005). To date, crops that show tolerance to ALS-inhibiting herbicides have been produced by various approaches, such as conventional mutation breeding, conventional transformation, and pinpoint mutagenesis via gene targeting based on information obtained from analyses of ALS mutants (Shimizu et al., 2005; Endo and Toki, 2013). On the other hand, weeds that show tolerance to ALS-inhibiting herbicides by cytochrome P450-mediated detoxification have also been reported (Powles and Yu, 2010). However, compared with target-site herbicide tolerance, little is known of the molecular mechanism of herbicide metabolism mediated by cytochrome P450. In rice (Oryza sativa), an herbicide-sensitive mutant has been produced by γ-ray irradiation (Zhang et al., 2002). This mutant showed 60-fold higher sensitivity to bensulfuron-methyl (BSM), a sulfonylurea herbicide, compared with wild-type rice (Pan et al., 2006). Genetic mapping and complementation tests revealed that a cytochrome P450, CYP81A6, is involved in BSM tolerance (Pan et al., 2006). As far as we know, this is the only example of the isolation and characterization of a cytochrome P450 gene involved in nontarget herbicide tolerance in rice.

Bispyribac sodium (BS), a pyrimidinyl carboxylate herbicide, is effective in controlling many annual and perennial weeds, with excellent selectivity on direct-seeded rice (Shimizu et al., 2002). Recently, it was reported that japonica rice varieties show higher sensitivity to BS compared with indica rice varieties at the early stages of plant growth (Ohno et al., 2008; Taniguchi et al., 2010). A mutated ALS gene confers BS tolerance in plants including rice (Shimizu et al., 2005; Endo and Toki, 2013). However, the deduced amino acid sequences were shown to be highly conserved among japonica and indica rice varieties, and ALS levels of sensitivity to BS were similar in japonica and indica rice varieties (Taniguchi et al., 2010). These results suggest the possibility that indica rice varieties might show higher tolerance to BS due to the acquisition of nontarget herbicide tolerance.

In this study, we isolated and characterized a novel cytochrome P450 gene, CYP72A31, involved in BS tolerance in rice. We also demonstrated that overexpression of CYP72A31 confers tolerance to ALS-inhibiting herbicides, including BS and BSM, in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana).

RESULTS

Cytochrome P450 Is Involved in BS Tolerance in indica Rice Varieties

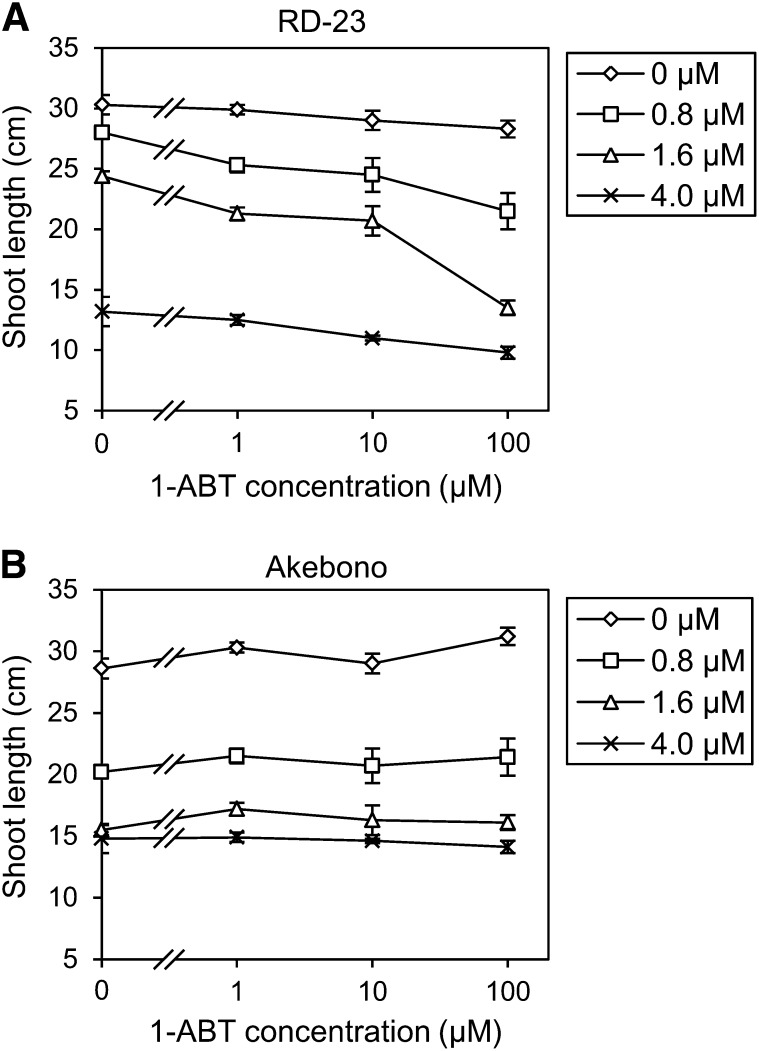

To check whether cytochrome P450 monooxygenase is involved in BS tolerance, we compared BS sensitivity in a japonica rice variety, Akebono, and an indica rice variety, RD-23, in the presence of 1-aminobenzotriazole (1-ABT), an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Growth of RD-23 seedlings treated with BS in combination with 1-ABT was suppressed compared with growth without 1-ABT (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, growth of Akebono seedlings treated with BS was similar both with and without 1-ABT (Fig. 1B), suggesting that cytochrome P450 monooxygenase is involved in BS tolerance in RD-23.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase enhanced BS sensitivity in RD-23. RD-23 (A) and Akebono (B) seedlings at the stage having a 10- to 15-cm third leaf were grown on medium containing BS and/or 1-ABT for 5 d. Diamonds, squares, triangles, and crosses indicate treatments with 0, 0.8, 1.6, and 4.0 μm BS, respectively. Values are averages ± se (n = 4 or 5).

Positional Cloning of the BS-TOLERANT Gene

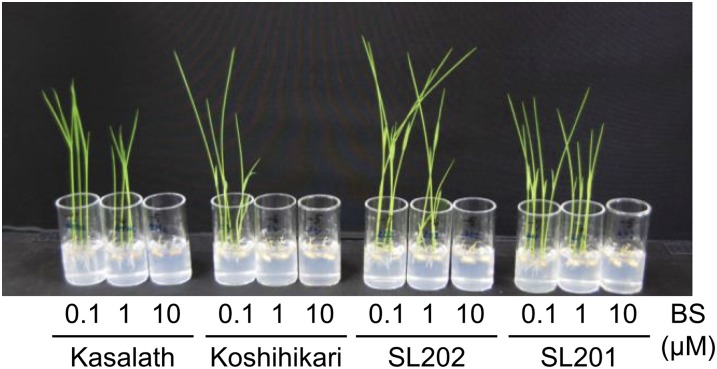

In further analyses, japonica elite rice variety Koshihikari and the indica model variety Kasalath were used to locate the quantitative trait locus (QTL) for BS tolerance. Composite interval mapping was performed using a population of 183 backcross inbred lines (BILs) derived from a cross of Koshihikari and Kasalath. A QTL with major effect for BS tolerance, named the BS-TOLERANT (BST) gene, was located to a 12.7-Mb region at the marker interval C178 to C122 on chromosome 1, and the Kasalath allele increased tolerance (Supplemental Table S1). In addition, we checked BS sensitivity in chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) carrying Kasalath segments in the Koshihikari background. SL201 and SL202, which harbor segments of chromosome 1 in Kasalath, showed BS tolerance similar to that of Kasalath (Fig. 2). This result was consistent with the result of composite interval mapping of BS sensitivity using BILs (Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 2.

BS sensitivity of japonica rice Koshihikari and indica rice Kasalath. BS sensitivity was tested among rice varieties Kasalath and Koshihikari as well as SL201 and SL202, which are CSSLs carrying Kasalath chromosome segments in the Koshihikari genetic background. BS was added to the medium at 0.1, 1, and 10 μm, respectively. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

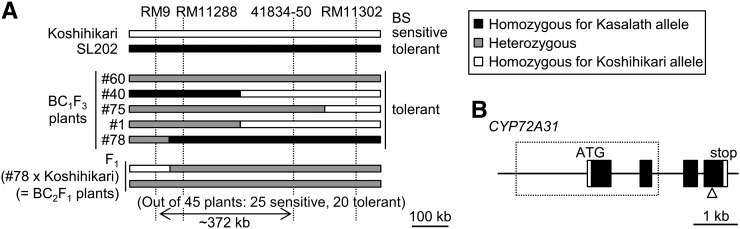

To isolate the BST gene, we attempted to delimit a candidate chromosomal region for the QTL detected by using an F2 population of SL202 × Koshihikari. BS tolerance was observed in 138 of 190 F2 plants derived from a cross between SL202 and Koshihikari, which fits a 3:1 ratio (χ2 = 0.34; P > 0.05). This result implies that BS tolerance is a dominant trait. Through genetic mapping using the progeny of the BC1F3 generation derived from a cross between SL202 and Koshihikari and the BC2F1 generation derived from a cross between BC1F3 line 78 and Koshihikari, the BST gene was narrowed down to a 372-kb region between RM9 and 41834-50 (Fig. 3A). Three putative genes encoding cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (Os01g0602200, Os01g0602400, and Os01g0602500) are annotated at this locus of the japonica model variety Nipponbare in the Rice Annotation Project Database (http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/; Kawahara et al., 2013; Sakai et al., 2013). On the cytochrome P450 home page (http://drnelson.uthsc.edu/CytochromeP450.html; Nelson et al., 2004), these genes correspond to CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33, respectively (Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). We compared the putative coding sequences of CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33 in Nipponbare and Kasalath. In Kasalath, all genes are thought to be functional based on information from the genomic sequence of chromosome 1 (Kanamori et al., 2013). On the other hand, it was predicted that the CYP72A31 gene is not functional in Nipponbare due to a 3.4-kb deletion including the region that corresponds to the first and second exons (Fig. 3B), although the CYP72A32 and CYP72A33 genes are functional. In Koshihikari, the large deletion seen in Nipponbare is not found in the CYP72A31 locus, and unlike in Nipponbare, CYP72A31 mRNA was detected by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (data not shown). However, sequence analysis of the CYP72A31 putative coding region revealed a –1 frame-shift mutation in the fourth exon of CYP72A31, creating a stop codon 15 nucleotides downstream of this deletion site (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. S3). It is noteworthy that the cytochrome P450 Cys heme-iron ligand signature (Phe-x-x-Gly-x-Arg-x-Cys-x-Gly) is located downstream of this deletion site in the fourth exon (Supplemental Fig. S3). Therefore, CYP72A31 of Koshihikari lacks this motif and thus would not play a role as a monooxygenase even if the transcripts were translated. These results indicated that BST is likely to correspond to the CYP72A31 gene.

Figure 3.

BST encodes a novel cytochrome P450 gene, CYP72A31, of rice. A, Graphical representation of the genotype of chromosome 1 in BC1F3 plants derived from a cross between SL202 and Koshihikari. Black, white, and gray bars indicate the regions homozygous for the Kasalath and Koshihikari alleles and the heterozygous region, respectively. Out of 45 F1 (line 78 × Koshihikari) plants, 20 were BS tolerant while 25 were sensitive. As a control experiment, out of 20 plants in which the region at the marker interval RM9 to 41834-50 was heterozygous, seven were BS tolerant while 13 were sensitive. This result was similar to that of line 78 × Koshihikari. B, Schematic representation of the BST gene (Os01g0602200, CYP72A31) in Kasalath. White and black boxes show the putative untranslated region and coding region of CYP72A31, respectively. The dotted rectangle and white triangle show the 3.4-kb and 1-bp deletions in the CYP72A31 gene of Nipponbare and Koshihikari, respectively. The disruptions of CYP72A31 in Nipponbare and Koshihikari are thought to be due to these deletions among many mutations. Bar = 1 kb.

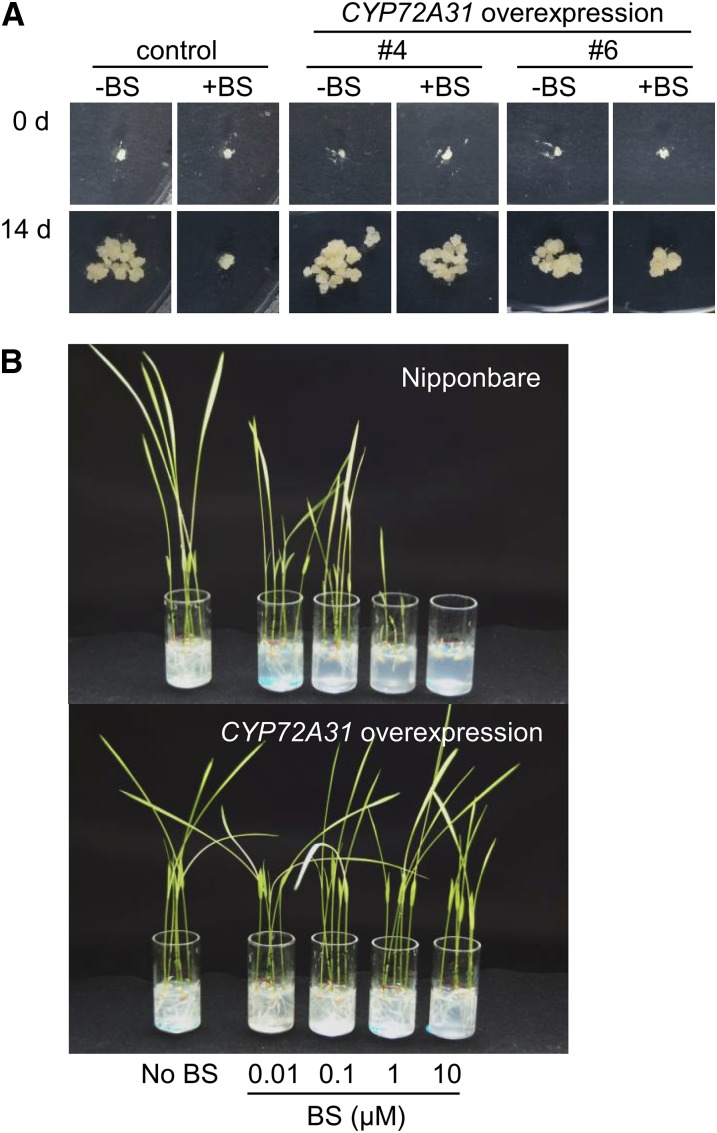

BS Sensitivity Test in CYP72A31-Overexpressing Plants

To confirm whether the BST gene is identical to CYP72A31, we checked BS sensitivity in transgenic rice of Nipponbare overexpressing CYP72A31, CYP72A32, or CYP72A33 complementary DNA (cDNA; Supplemental Fig. S4). As expected, CYP72A31-overexpressing calli showed higher tolerance to 0.25 μm BS compared with control calli, while CYP72A32- or CYP72A33-overexpressing calli showed no obvious tolerance to 0.25 μm BS (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Fig. S5). Interestingly, transgenic callus lines in which CYP72A31 mRNA accumulated at a relatively lower level showed no significant tolerance to 0.75 μm BS (Supplemental Fig. S6A), suggesting that there is a positive correlation between BS tolerance and CYP72A31 expression level. To determine the CYP72A31 expression level sufficient to confer 0.75 μm BS tolerance, we checked BS sensitivity in CYP72A31-overexpressing calli of Kasalath. A BS sensitivity test showed that 40- to 100-fold more CYP72A31 mRNA was required to confer tolerance to 0.75 μm BS compared with control callus of Kasalath (Supplemental Fig. S6B).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of the CYP72A31 gene confers BS tolerance in Nipponbare. A, BS sensitivity in transformed calli overexpressing the CYP72A31 gene. Rice calli in the T0 generation were transferred to fresh medium containing 0.25 μm BS and cultivated for 14 d. Transgenic calli overexpressing the CYP72A31 gene grew vigorously, although control calli transformed with GFP-expressing vector ceased growth. B, BS sensitivity in transgenic rice seedlings overexpressing the CYP72A31 gene. Transgenic seeds were germinated and grown on medium containing 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 μm BS. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Twenty-five lines of regenerated plantlets overexpressing CYP72A31 of Nipponbare were transferred to medium containing 1 μm BS. The roots of CYP72A31-overexpressing seedlings grew vigorously under BS treatment in seven of these lines, although roots of control plants ceased growth in all lines (Supplemental Fig. S7). Surprisingly, we found that CYP72A31-overexpressing rice plants of Nipponbare showed over 100-fold higher tolerance to BS compared with nontransformant (Fig. 4B).

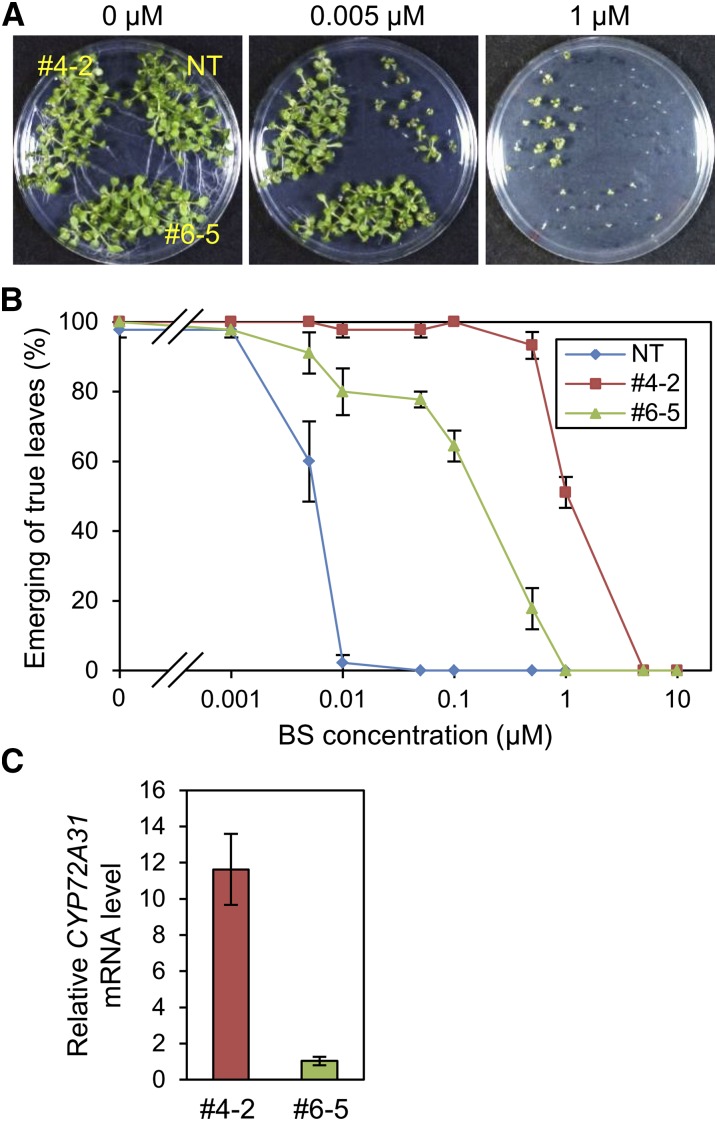

To test whether the CYP72A31 gene confers BS tolerance in dicots, we produced transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33. As in rice, Arabidopsis seedlings overexpressing CYP72A31 showed higher BS tolerance, although BS sensitivity in Arabidopsis seedlings overexpressing CYP72A32 or CYP72A33 was comparable to that of nontransformant (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S8). Line 4-2, in which the CYP72A31 mRNA level was higher, showed higher tolerance to BS than line 6-5 (Fig. 5). Taking these results together, we concluded that the CYP72A31 gene is the BST gene and that the expression level of the CYP72A31 gene parallels the level of BS tolerance.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of the CYP72A31 gene confers BS tolerance in Arabidopsis. A and B, BS sensitivity in transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings overexpressing CYP72A31 (lines 4-2 and 6-5). Transgenic seeds were germinated on medium containing 0.001, 0.005, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, or 10 μm BS. After 10 d of cultivation, plants were checked for the emergence of true leaves. Data are means ± se of three experiments. NT, Nontransformant. C, mRNA levels of the CYP72A31 gene in the leaves of lines 4-2 and 6-5. mRNA levels were normalized to the Arabidopsis elongation factor1 αA4 (AtEF1αA4) mRNA level as a control. The CYP72A31 mRNA level in line 4-2 was higher than that in line 6-5. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Analysis of CYP72A31 Gene Expression

In a previous study, the growth of Kasalath callus was similar to that of Nipponbare under BS conditions, although seedlings of Kasalath showed higher BS tolerance compared with Nipponbare (Taniguchi et al., 2010). Since there is a positive relationship between CYP72A31 mRNA level and BS tolerance (Figs. 4 and 5; Supplemental Fig. S6), it was assumed that the difference in BS sensitivity between seedlings and callus of Kasalath is due to expression levels of the CYP72A31 gene. To confirm this, we determined the mRNA levels of the CYP72A31 gene in shoots, roots, and calli. As expected, expression levels of the CYP72A31 gene in shoots and roots of 7-d-old seedlings were much higher than those in primary and secondary calli (Table I), suggesting that BS tolerance levels among organs in Kasalath are caused by differences in CYP72A31 mRNA amounts.

Table I. Expression analysis of CYP72A31 in Nipponbare and Kasalath.

Relative mRNA levels of the CYP72A31 gene in the shoots and roots of 7-d-old seedlings, 7-d-old primary callus, and 21-d-old secondary callus are shown. All mRNA levels were normalized to the OsActin1 mRNA level as a control. Data shown are means ± sd of three separate PCR analyses. RT-PCR experiments were performed twice using different RNA samples as templates, with similar results. N.D., Not detected.

| Sample | Nipponbare | Kasalath |

|---|---|---|

| Shoots | N.D. | 0.139 ± 0.017 |

| Roots | N.D. | 0.636 ± 0.141 |

| Primary callus | N.D. | 0.011 ± 0.001 |

| Secondary callus | N.D. | 0.033 ± 0.005 |

Comparison of ALS-Inhibiting Herbicide Tolerance by CYP72A31 and CYP81A6

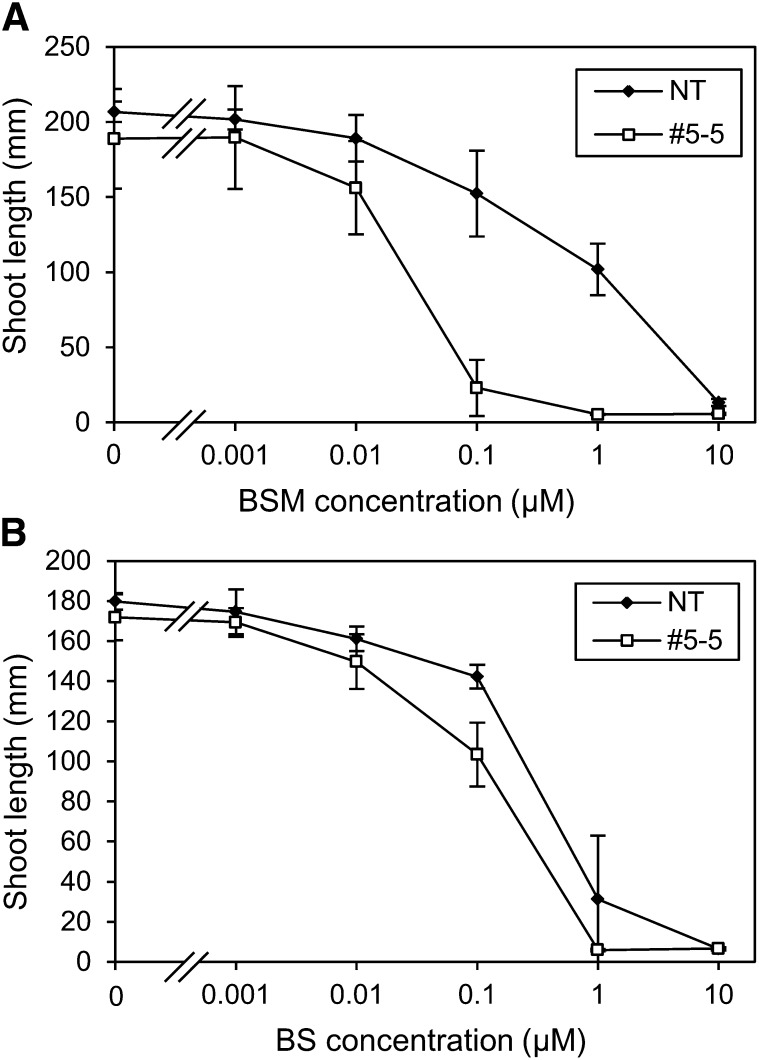

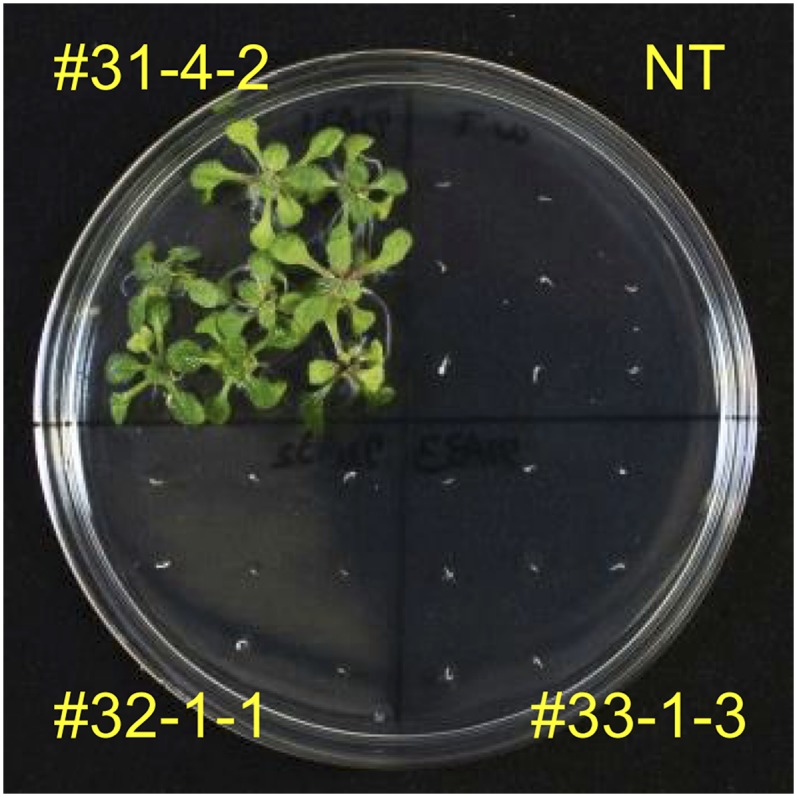

It was reported that cyp81a6 mutant rice showed high sensitivity to bentazon and sulfonylurea herbicides (e.g. BSM), which have different chemical structures from pyrimidinyl carboxylate herbicides (e.g. BS; Zhang et al., 2002; Pan et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2012). It was also reported that japonica rice varieties Kamenoo-4 and Joshu tended to be more sensitive to BSM than indica rice varieties IR-8 and IR-26 (Kobayashi et al., 1995), suggesting the possibility that, in addition to the CYP81A6 gene, the CYP72A31 gene is involved in BSM tolerance. To check whether the CYP72A31 gene confers BSM tolerance, the BSM sensitivity in CYP72A31-overexpressing Arabidopsis was checked. As expected, Arabidopsis overexpressing CYP72A31 (line 31-4-2) showed more than 28-fold higher tolerance to BSM, although Arabidopsis overexpressing CYP72A32 or CYP72A33 (line 32-1-1 or 33-1-3, respectively) showed no BSM tolerance, as with BS (Fig. 6). On the other hand, we produced transgenic rice plants in which CYP81A6 expression levels are repressed by RNA interference (RNAi; Nipponbare line 5-5) and checked their sensitivity to BS. The mRNA levels of the CYP81A6 gene in line 5-5 were 10- to 20-fold lower compared with nontransformant (Supplemental Fig. S9). Plants of rice line 5-5 showed high sensitivity to BSM compared with nontransformant (Fig. 7A), similar to a previous report (Lin et al., 2008). These results suggested that the combination of CYP72A31 and CYP81A6 genes could confer additive tolerance to BSM.

Figure 6.

BSM sensitivity upon overexpression of CYP72A31 in Arabidopsis. The BSM sensitivity in nontransformant (NT) and transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings is shown. Lines 31-4-2, 32-1-1, and 33-1-3 are transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33, respectively. Transgenic seeds were germinated on medium containing 3 nm BSM. [See online article for color version of this figure.]

Figure 7.

The CYP81A6 gene is barely involved in BS tolerance. BSM (A) and BS (B) sensitivity in CYP81A6 knockdown rice seedlings is shown. Rice seeds were germinated and grown on medium containing 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, or 10 μm BSM or BS for 7 d. Black diamonds and white squares indicate nontransformant (NT) and CYP81A6 knockdown plants (line 5-5), respectively. Values are averages ± sd (n = 4).

We further checked whether the CYP81A6 gene is involved in BS tolerance. The sensitivity test revealed that line 5-5 showed sensitivity to BS similar to that of nontransformant (Fig. 7B). This result shows that, unlike the CYP72A31 gene, the CYP81A6 gene is barely involved, if at all, in BS tolerance.

DISCUSSION

The CYP72A31 Gene Encodes a Novel Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenase and Is Involved in ALS-Inhibiting Herbicide Tolerance

Of the total of 14 CYP72A genes in the rice genome, 13 are located on chromosome 1 (Supplemental Fig. S1). Among them, nine CYP72A genes (CYP72A17–CYP72A25) are localized to an approximately 80-kb region of chromosome 1. On the other hand, genes CYP72A31 to CYP72A33 are localized to approximately 23- and 28-kb regions of chromosome 1, distinct from a cluster of nine CYP72A genes in the Nipponbare and Kasalath genomes, respectively. In Kasalath, the amino acid identities between CYP72A31 and CYP72A32, CYP72A31 and CYP72A33, and CYP72A32 and CYP72A33 are 85%, 84%, and 90%, respectively (Supplemental Fig. S2). CYP72A21 expression is reported to be induced by treatment with various herbicides, including chlorsulfuron, a sulfonylurea herbicide (Hirose et al., 2007). CYP72A18 catalyzes (ω-1)-hydroxylation of the herbicide pelargonic acid (Imaishi and Matumoto, 2007). These previous reports together with our results here suggest that CYP72A genes are, indeed, widely involved in xenobiotic responses.

The biological functions of CYP72A proteins are only poorly elucidated to date, although they are hugely diverse (Nelson and Werck-Reichhart, 2011). In Catharanthus roseus, the CYP72A1 gene encodes a secologanin synthase that converts loganin into secologanin (Irmler et al., 2000). CYP72A154 and CYP72A63 are involved in the glycyrrhizin biosynthesis pathway in licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) and Medicago truncatula, respectively (Seki et al., 2011). Such findings reveal that CYP72A proteins work as ring-opening and triterpene-oxidizing enzymes. In rice, expression levels of CYP72A18, CYP72A19, CYP72A22, and CYP72A23 were reported to be altered by infection with rice blast (Wang et al., 2004), suggesting the possibility that the CYP72A31 gene might be involved not only in herbicide detoxification but also in secondary metabolism. It will be of great interest to discover which compounds are targets of the CYP72A31 enzyme and to elucidate its evolutionary significance.

Application of CYP72A31 and CYP81A6 Genes in Weed Management and Herbicide Screening

It is important and useful for the development of novel herbicides to analyze the biochemical and enzymatic properties of CYP72A31. Moreover, it is of interest to identify the products of herbicides that are metabolized by CYP72A31. In a previous report, O-demethylation of BS was detected as one of the major pathways of BS metabolism in rice and wheat (Triticum aestivum) seedlings (Matsushita et al., 1994). This metabolite and/or further processing of it might be catalyzed by CYP72A31. We showed that the CYP72A31 gene confers tolerance not only to BS but also to BSM in Arabidopsis (Figs. 5 and 6). This result suggested that the CYP72A31 and CYP81A6 genes have redundant functions in BSM detoxification, to a varying degree, although they belong to different families, clades in cytochrome P450 being deeply divergent. It is thought that herbicide detoxification activities are determined by factors such as substrate specificity and amount of enzyme, which are regulated by expression levels and patterns. The elucidation of the molecular mechanism of ALS-inhibiting herbicides involving CYP72A31 and/or CYP81A6 will be the subject of future research.

Structural data describing the ALS protein in complex with ALS-inhibiting herbicides have been reported (McCourt et al., 2006). It has also been shown that it is difficult to predict substrate preferences from primary sequences in CYP72A proteins (Nelson and Werck-Reichhart, 2011). Thus, resolution of the crystal structure of CYP72A31 will lead to new insights in the development of novel herbicides with novel crop-weed selectivity. Our results show that overexpression of the CYP72A31 gene conferred BS tolerance on rice and Arabidopsis, although overexpression of the CYP72A32 or CYP72A33 gene did not confer BS tolerance (Figs. 4 and 5; Supplemental Figs. S5 and S8). Moreover, CYP81A6 knockdown rice plants did not exhibit enhanced BS sensitivity (Fig. 7). On the other hand, we showed that both CYP81A6 and CYP72A31 are involved in BSM tolerance (Figs. 6 and 7). Combined with these results, knowledge of the crystal structure and the cytochrome P450 substrate-binding motif among these proteins will offer new information about the specificity to bind BS and BSM, information that can be applied to the molecular evolution of cytochrome P450 for the production of herbicide-tolerant crops.

The CYP72A31 gene is a useful genetic resource to develop herbicide tolerance in rice. We are currently producing a near-isogenic line of Koshihikari harboring a functional CYP72A31 gene derived from Kasalath. Moreover, we succeeded in using somaclonal mutagenesis to introduce the point mutation W548L into the ALS gene to confer tolerance to multiple ALS-inhibiting herbicides in Koshihikari (data not shown). We expect to produce herbicide-tolerant Koshihikari easily by genetic stacking of the mutated ALS gene and the functional CYP72A31 gene, which will confer target-site and non-target-site herbicide tolerance, respectively. Plants with both target-site and non-target-site herbicide tolerance are safer compared with plants exhibiting only one or the other, because excess herbicide that cannot bind the ALS protein can be detoxified rapidly in such plants. Moreover, the CYP81A6 gene is involved in tolerance to two different classes of herbicides, bentazon and sulfonylurea herbicides such as BSM, in rice, Arabidopsis, and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Zhang et al., 2002; Pan et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2012). The heterologous expression of CYP72A31 and/or CYP81A6 genes by transgenic approaches provides the potential for much greater flexibility of weed management in crops.

Application of the CYP72A31 Gene to a Broad Array of Technologies

In this study, we demonstrated that the CYP72A31 gene can confer tolerance to ALS-inhibiting herbicides in rice and Arabidopsis, suggesting that, like CYP81A6, the CYP72A31 gene can be applied to a broad array of technologies as follows.

First, the CYP72A31 gene can be used as a selectable marker in genetic transformation. A BS-insensitive mutant ALS gene has been used widely as a positive marker to obtain transformed cells and plants under BS selection. For example, a combination of a mutated rice ALS gene and BS selection has been applied in rice (Osakabe et al., 2005; Okuzaki et al., 2007; Wakasa et al., 2007; Taniguchi et al., 2010), wheat (Ogawa et al., 2008), tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea; Sato et al., 2013), Arabidopsis (Kawai et al., 2010), and soybean (Glycine max; Tougou et al., 2009). Like the mutated ALS gene, the CYP81A6 gene has also been reported as a selection marker with BSM in Arabidopsis, cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), and tobacco plants (Ke et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012). However, optimization of CYP72A31 gene expression levels and the herbicide concentration in the selection medium might be necessary to establish a transformation system using the CYP72A31 gene as a selection marker, since CYP72A31 mRNA levels are crucial to confer BS tolerance in rice and Arabidopsis (Fig. 5; Supplemental Fig. S6).

Second, the CYP72A31 gene can be used to ensure high varietal purity in hybrid seed production systems. Male-sterile rice plants in which the CYP81A6 gene was disrupted with γ-ray irradiation and male-sterile tall fescue plants transformed with a mutated ALS gene have been developed (Wang et al., 2012; Sato et al., 2013). No apparent negative phenotypes were observed in these male-sterile rice mutants and their F1 hybrids with other varieties, and contamination with false hybrid plants caused by self-pollination can be addressed, as these are completely killed off by treatment with bentazon (Wang et al., 2012). It is expected that the difference in BS sensitivity depending on the CYP72A31 gene between japonica and indica rice varieties can be more easily applied to the hybrid seed production system in rice than the CYP81A6 gene. This is because, unlike CYP81A6, the CYP72A31 gene is thought to be not functional in japonica but it is functional in indica varieties, since indica and indica-derived varieties showed higher BS tolerance compared with japonica varieties (Ohno et al., 2008; Taniguchi et al., 2010).

Third, knockdown of the CYP72A31 gene could work as a useful negative selection marker in rice plants. Varieties that show dominant herbicide sensitivity can be applied to so-called “terminator technology” in crops (i.e. gene containment systems to suppress gene flow, including the spread of transgenes into the environment) using techniques such as maternal inheritance, male sterility, and seed sterility (Daniell, 2002). Indeed, transgene containment was achieved successfully by knockdown of the CYP81A6 gene in rice (Lin et al., 2008).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primers

Primers used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Plant Materials and Treatments

Rice (Oryza sativa varieties Akebono, RD-23, Nipponbare, Koshihikari, and Kasalath) and Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Columbia-0 were used in this study. BILs and CSSLs originated from a cross between Koshihikari and Kasalath and were provided by the Rice Genome Resource Center (http://www.rgrc.dna.affrc.go.jp/ineKKBIL182.html and http://www.rgrc.dna.affrc.go.jp/ineKKCSSL39.html; Ma et al., 2002; Ebitani et al., 2005).

For genetic mapping of the BST gene, germinated rice seeds were grown on medium composed of 1 μm BS (Kumiai Chemical Industry), 1.6 g L−1 Hoagland mix (Sigma-Aldrich), and 3 g L−1 gelrite (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) at 27°C for 7 to 9 d. We evaluated BS sensitivity based on the shoot length of these plants. To test BS sensitivity in transgenic rice calli overexpressing the CYP72A31 gene, clonally propagated calli were transferred to N6D medium (Toki, 1997; Toki et al., 2006) containing BS and grown at 31°C to 33°C for 14 d. To test BS sensitivity in transgenic rice plants overexpressing the CYP72A31 gene, plantlets were transferred to Murashige and Skoog medium (Toki, 1997; Toki et al., 2006) containing 1 μm BS and grown at 27°C for 10 d. For the test of BS or BSM sensitivity in CYP81A6 knockdown rice plants, germinated rice seeds were grown on medium containing various concentrations of BS or BSM at 27°C for 1 week. We evaluated the sensitivity based on the shoot length of these plants. To test BS and BSM sensitivity in transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the CYP72A31 gene, T3 seeds were sown on Murashige and Skoog medium containing various concentrations of BS or 3 nm BSM and grown at 22°C for 10 or 18 d, respectively. We evaluated the BS sensitivity based on the emergence of true leaves.

Genetic Mapping of the BST Gene

Line SL202, which has a Kasalath segment on chromosome 1 in a Koshihikari background, was crossed with Koshihikari, and the F1 plant was crossed with Koshihikari to obtain BC1F1. This plant was selfed twice to obtain BC1F3 seeds. To narrow down the location of the BST gene, we evaluated the BS tolerance of 82 BC1F3 plants. One BC1F3 plant, line 78, was crossed to Koshihikari to obtain BC2F1 seeds, and 45 BC2F1 plants were evaluated for their BS tolerance. The molecular markers used for genotyping are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Extraction of Total RNA and RT-PCR

For extraction of RNA, primary and secondary calli, shoots, and roots in rice and true leaves in Arabidopsis were harvested, immediately frozen in liquid N2, and stored at −80°C. Total RNA was extracted from samples using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For RT-PCR for CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33 genes, total RNA was used for RT using the oligo(dT)20 primer with ReverTra Ace (Toyobo). Transcript levels of each gene were measured by real-time PCR using an ABI7300 (Life Technologies) and the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocols with the primer sets CYP72A31 RT-F/CYP72A31 RT-R, CYP72A32 RT-F/CYP72A32 RT-R, CYP72A33 RT-F/CYP72A33 RT-R, OsAct1 RT-F/OsAct1 RT-R, and AtEF1αA4 RT-F/AtEF1αA4 RT-R. A PCR fragment of each gene was used to make standard curves for quantification. For RT-PCR of the CYP81A6 gene, total RNA treated with DNaseI (DNase RT Grade for Heat Stop; Nippon Gene) was used for RT using the oligo(dT) primer with the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TaKaRa Bio). Transcript levels of each gene were measured by real-time PCR using the Thermal Cycler Dice TP800 (TaKaRa Bio) and SYBR Green I (TaKaRa Bio) according to the manufacturer’s protocols with the primer sets CYP81A6 RT-F/CYP81A6 RT-R and CA000683_F/CA000683_R (for rice Actin1). A PCR fragment of each gene was used to prepare standard curves for quantification.

Vector Construction and Transformation

To construct overexpression vectors, reverse-transcribed cDNAs of CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33 genes of Nipponbare and Kasalath were prepared with high-fidelity DNA polymerase KOD -Plus- (Toyobo) using primer sets CYP72A31 F/CYP72A31 R, CYP72A32 F/CYP72A32 R, and CYP72A33 F/CYP72A33 R. The resultant PCR fragments were cloned into the vector pBluescript SK− using EcoRV. The sequences of cDNA clones were analyzed with an ABI3130 sequencer (Life Technologies). To construct overexpression vectors for CYP72A31 and CYP72A33 genes, the 1.8-kb fragment containing CYP72A31 and CYP72A33 cDNAs digested from these vectors using EcoRI/SalI was replaced with a GFP::Tnos fragment in the vector pCAMBIA1390-sGFP digested with EcoRI/SalI. To construct an overexpression vector for CYP72A32, a 1.8-kb fragment containing CYP72A32 cDNA was amplified by PCR from a cDNA clone using KOD -plus- (Toyobo) with the primer set CYP72A32 F2/M13 Rv. The resultant PCR fragment digested by EcoRI/SalI was replaced with a GFP::Tnos fragment in the vector pCAMBIA1390-sGFP digested with EcoRI/SalI. To construct the RNAi vector, a 328-bp fragment containing CYP81A6 was amplified by PCR from cDNA using KOD FX (Toyobo) with the primer set CYP81A6 F/CYP81A6 R. The resultant PCR fragment was cloned into the vector pENTR/D-TOPO using directional TOPO cloning methods (Life Technologies) to yield an entry vector. The RNAi vector was produced with the use of an LR clonase (Life Technologies) that catalyzes the recombination between an entry vector and the pANDA vector (Miki and Shimamoto, 2004).

The binary vectors described above were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 (Hood et al., 1993) by electroporation. A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation using rice callus derived from mature seeds was performed according to our previous studies (Toki, 1997; Toki et al., 2006). A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation in Arabidopsis was performed by the inflorescence infiltration method (Bechtold et al., 1993).

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers Kasalath CYP72A31 (AB907219), Kasalath CYP72A32 (AB907220), Kasalath CYP72A33 (AB907221), Nipponbare CYP72A32 (AB907222) and Nipponbare CYP72A33 (AB907223).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. The phylogenic tree of CYP72A protein in rice, maize, and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S2. Alignment of CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33 protein in Nipponbare and Kasalath.

Supplemental Figure S3. The alignment of CYP72A31 in Koshihikari and Kasalath.

Supplemental Figure S4. Structure of CYP72A31, CYP72A32, and CYP72A33 overexpression vectors.

Supplemental Figure S5. BS sensitivity of overexpression of CYP72A32 and CYP72A33 genes in Nipponbare.

Supplemental Figure S6. Correlation of CYP72A31 expression levels and BS tolerance in rice callus.

Supplemental Figure S7. Overexpression of CYP72A31 gene confers BS tolerance in regenerated seedlings of Nipponbare.

Supplemental Figure S8. BS sensitivity of overexpression of CYP72A32 and CYP72A33 genes in Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S9. CYP81A6 knockdown rice plants.

Supplemental Table S1. Putative QTL for BS tolerance detected through composite interval mapping using 183 BILs (Koshihikari/Kasalath/Koshihikari).

Supplemental Table S2. Primers used in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Helen Rothnie for English editing, Ko Shimamoto for providing pANDA vector, and Yasuo Niwa for providing synthetic GFP. We also thank Masaki Endo and Namie Ohtsuki for discussion and Akiko Mori, Kiyoko Amagai, Akemi Nagashii, and Fukuko Suzuki for technical assistance.

Glossary

- ALS

acetolactate synthase

- BSM

bensulfuron-methyl

- BS

bispyribac sodium

- 1-ABT

1-aminobenzotriazole

- QTL

quantitative trait locus

- BIL

backcross inbred line

- CSSL

chromosome segment substitution line

- RT

reverse transcription

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- RNAi

RNA interference

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan (grant to H.S. and S.T.).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

The online version of this article contains Web-only data.

Articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Bechtold N, Ellis J, Pelletier G. (1993) In planta Agrobacterium mediated gene transfer by infiltration of adult Arabidopsis thaliana plants. C R Acad Sci Paris Life Sci 316: 1194–1199 [Google Scholar]

- Daniell H. (2002) Molecular strategies for gene containment in transgenic crops. Nat Biotechnol 20: 581–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebitani T, Takeuchi Y, Nonoue Y, Yamamoto T, Takeuchi K, Yano M. (2005) Construction and evaluation of chromosome segment substitution lines carrying overlapping chromosome segments of indica rice cultivar ‘Kasalath’ in a genetic background of japonica elite cultivar ‘Koshihikari’. Breed Sci 55: 65–73 [Google Scholar]

- Endo M, Toki S. (2013) Creation of herbicide-tolerant crops by gene targeting. J Pestic Sci 38: 49–59 [Google Scholar]

- Hirose S, Kawahigashi H, Tagiri A, Imaishi H, Ohkawa H, Ohkawa Y. (2007) Tissue-specific expression of rice CYP72A21 induced by auxins and herbicides. Plant Biotechnol Rep 1: 27–36 [Google Scholar]

- Hood EE, Gelvin SB, Melchers LS, Hoekema A. (1993) New Agrobacterium helper plasmids for gene-transfer to plants. Transgenic Res 2: 208–218 [Google Scholar]

- Imaishi H, Matumoto S. (2007) Isolation and functional characterization in yeast of CYP72A18, a rice cytochrome P450 that catalyzes (ω-1)-hydroxylation of the herbicide pelargonic acid. Pestic Biochem Physiol 88: 71–77 [Google Scholar]

- Irmler S, Schröder G, St-Pierre B, Crouch NP, Hotze M, Schmidt J, Strack D, Matern U, Schröder J. (2000) Indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus: new enzyme activities and identification of cytochrome P450 CYP72A1 as secologanin synthase. Plant J 24: 797–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori H, Fujisawa M, Katagiri S, Oono Y, Fujisawa H, Karasawa W, Kurita K, Sasaki H, Mori S, Hamada M, et al. (2013) A BAC physical map of aus rice cultivar ‘Kasalath’, and the map-based genomic sequence of ‘Kasalath’ chromosome 1. Plant J 76: 699–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y, de la Bastide M, Hamilton JP, Kanamori H, McCombie WR, Ouyang S, Schwartz DC, Tanaka T, Wu J, Zhou S, et al. (2013) Improvement of the Oryza sativa Nipponbare reference genome using next generation sequence and optical map data. Rice 6: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai K, Kaku K, Izawa N, Shimizu M, Kobayashi H, Shimizu T. (2010) Transformation of Arabidopsis by mutated acetolactate synthase genes from rice and Arabidopsis that confer specific resistance to pyrimidinylcarboxylate-type ALS inhibitors. Plant Biotechnol 27: 75–84 [Google Scholar]

- Ke LP, Liu RE, Chu BJ, Yu XS, Sun J, Jones B, Pan G, Cheng XF, Wang HZ, Zhu SJ, et al (2012) Cell suspension culture-mediated incorporation of the rice bel gene into transgenic cotton. PLoS ONE 7: e39974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Yogo Y, Sugiyama H. (1995) Differential growth response of rice cultivars to pyrazosulfuron-ethyl. Weed Research Japan 40: 104–109 [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Fang J, Xu XL, Zhao T, Cheng JA, Tu JM, Ye GY, Shen ZC. (2008) A built-in strategy for containment of transgenic plants: creation of selectively terminable transgenic rice. PLoS ONE 3: e1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Liu SQ, Wang F, Wang YQ, Liu KD. (2012) Expression of a rice CYP81A6 gene confers tolerance to bentazon and sulfonylurea herbicides in both Arabidopsis and tobacco. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 109: 419–428 [Google Scholar]

- Ma JF, Shen RF, Zhao ZQ, Wissuwa M, Takeuchi Y, Ebitani T, Yano M. (2002) Response of rice to Al stress and identification of quantitative trait loci for Al tolerance. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 652–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita H, Hukai Y, Unai T, Ishikawa K, Yusa Y (1994) The report concerning a novel herbicide, KIH-2023: adsorption, translocation and metabolism of KIH-2023 in rice and wheat seedlings. In Abstract of Annual Meeting Pesticide Science Society Japan, Tokyo: 127 (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- McCourt JA, Pang SS, King-Scott J, Guddat LW, Duggleby RG. (2006) Herbicide-binding sites revealed in the structure of plant acetohydroxyacid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 569–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki D, Shimamoto K. (2004) Simple RNAi vectors for stable and transient suppression of gene function in rice. Plant Cell Physiol 45: 490–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D, Werck-Reichhart D. (2011) A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J 66: 194–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR, Schuler MA, Paquette SM, Werck-Reichhart D, Bak S. (2004) Comparative genomics of rice and Arabidopsis: analysis of 727 cytochrome P450 genes and pseudogenes from a monocot and a dicot. Plant Physiol 135: 756–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T, Kawahigashi H, Toki S, Handa H. (2008) Efficient transformation of wheat by using a mutated rice acetolactate synthase gene as a selectable marker. Plant Cell Rep 27: 1325–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S, Watanabe O, Hanai R, Endou Y, Fujisawa S. (2008) Safety of several forage rice varieties to bispyribac-sodium. Jpn J Crop Sci 76: 250–251 [Google Scholar]

- Okuzaki A, Shimizu T, Kaku K, Kawai K, Toriyama K. (2007) A novel mutated acetolactate synthase gene conferring specific resistance to pyrimidinyl carboxy herbicides in rice. Plant Mol Biol 64: 219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osakabe K, Endo M, Kawai K, Nishizawa Y, Ono K, Abe K, Ishikawa Y, Nakamura H, Ichikawa H, Nishimura S, et al (2005) The mutant form of acetolactate synthase genomic DNA from rice is an efficient selectable marker for genetic transformation. Mol Breed 16: 313–320 [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, Zhang XY, Liu KD, Zhang JW, Wu XZ, Zhu J, Tu JM. (2006) Map-based cloning of a novel rice cytochrome P450 gene CYP81A6 that confers resistance to two different classes of herbicides. Plant Mol Biol 61: 933–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powles SB, Yu Q (2010) Evolution in action: plants resistant to herbicides. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 317–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H, Lee SS, Tanaka T, Numa H, Kim J, Kawahara Y, Wakimoto H, Yang CC, Iwamoto M, Abe T, et al. (2013) Rice Annotation Project Database (RAP-DB): an integrative and interactive database for rice genomics. Plant Cell Physiol 54: e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Shimizu T, Kawai K, Kaku K, Arakawa A, Tachibana T, Takamizo T. (2013) Herbicide-resistant tall fescue with cytoplasmic male sterility selected by a mutated rice acetolactate synthase gene. Crop Sci 53: 201–207 [Google Scholar]

- Seki H, Sawai S, Ohyama K, Mizutani M, Ohnishi T, Sudo H, Fukushima EO, Akashi T, Aoki T, Saito K, et al (2011) Triterpene functional genomics in licorice for identification of CYP72A154 involved in the biosynthesis of glycyrrhizin. Plant Cell 23: 4112–4123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Kaku K, Kawai K, Miyazawa T, Tanaka Y (2005) Molecular characterization of acetolactate synthase in resistant weeds and crops. In JM Clark, H Ohkawa, eds, Environmental Fate and Safety Management of Agrochemicals. ACS Symposium Series, Vol 899. American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, pp 255–271 [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Nakayama I, Nagayama K, Miyazawa T, Nezu Y (2002) Acetolactate synthase inhibitors. In P Böger, K Wakabayashi, K Hirai, eds, Herbicide Classes in Development. Mode of Action, Targets, Genetic Engineering, Chemistry. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, pp 1–41 [Google Scholar]

- Siminszky B. (2006) Plant cytochrome P450-mediated herbicide metabolism. Phytochem Rev 5: 445–458 [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y, Kawata M, Ando I, Shimizu T, Ohshima M. (2010) Selecting genetic transformants of indica and indica-derived rice cultivars using bispyribac sodium and a mutated ALS gene. Plant Cell Rep 29: 1287–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S. (1997) Rapid and efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in rice. Plant Mol Biol Rep 15: 16–21 [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Hara N, Ono K, Onodera H, Tagiri A, Oka S, Tanaka H. (2006) Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J 47: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tougou M, Yamagishi N, Furutani N, Kaku K, Shimizu T, Takahata Y, Sakai J, Kanematsu S, Hidaka S. (2009) The application of the mutated acetolactate synthase gene from rice as the selectable marker gene in the production of transgenic soybeans. Plant Cell Rep 28: 769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakasa Y, Ozawa K, Takaiwa F. (2007) Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of a low glutelin mutant of ‘Koshihikari’ rice variety using the mutated-acetolactate synthase gene derived from rice genome as a selectable marker. Plant Cell Rep 26: 1567–1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QZ, Fu HW, Huang JZ, Zhao HJ, Li YF, Zhang B, Shu QY. (2012) Generation and characterization of bentazon susceptible mutants of commercial male sterile lines and evaluation of their utility in hybrid rice production. Field Crops Res 137: 12–18 [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Li Q, He ZH. (2004) Blast fungus-induction and developmental and tissue-specific expression of a rice P450 CYP72A gene cluster. Chin Sci Bull 49: 131–135 [Google Scholar]

- Werck-Reichhart D, Hehn A, Didierjean L. (2000) Cytochromes P450 for engineering herbicide tolerance. Trends Plant Sci 5: 116–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JS, Tranel PJ, Stewart CN., Jr (2007) Non-target-site herbicide resistance: a family business. Trends Plant Sci 12: 6–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Xu Y, Wu X, Zhu L. (2002) A bentazon and sulfonylurea sensitive mutant: breeding, genetics and potential application in seed production of hybrid rice. Theor Appl Genet 105: 16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.