Abstract

In gene regulatory circuits, the expression of individual genes is commonly modulated by a set of regulating gene products, which bind to a gene’s cis-regulatory region. This region encodes an input-output function, referred to as signal-integration logic, that maps a specific combination of regulatory signals (inputs) to a particular expression state (output) of a gene. The space of all possible signal-integration functions is vast and the mapping from input to output is many-to-one: for the same set of inputs, many functions (genotypes) yield the same expression output (phenotype). Here, we exhaustively enumerate the set of signal-integration functions that yield idential gene expression patterns within a computational model of gene regulatory circuits. Our goal is to characterize the relationship between robustness and evolvability in the signal-integration space of regulatory circuits, and to understand how these properties vary between the genotypic and phenotypic scales. Among other results, we find that the distributions of genotypic robustness are skewed, such that the majority of signal-integration functions are robust to perturbation. We show that the connected set of genotypes that make up a given phenotype are constrained to specific regions of the space of all possible signal-integration functions, but that as the distance between genotypes increases, so does their capacity for unique innovations. In addition, we find that robust phenotypes are (i) evolvable, (ii) easily identified by random mutation, and (iii) mutationally biased toward other robust phenotypes. We explore the implications of these latter observations for mutation-based evolution by conducting random walks between randomly chosen source and target phenotypes. We demonstrate that the time required to identify the target phenotype is independent of the properties of the source phenotype.

Keywords: Evolutionary Innovation, Random Boolean Circuit, Genetic Regulation, Genotype Networks, Genotype-Phenotype Map

1 Introduction

Living organisms exhibit two seemingly paradoxical properties: They are robust to genetic change, yet highly evolvable (Wagner, 2005). These properties appear contradictory because the former requires that genetic alterations leave the phenotype intact, while the latter requires that these alterations explore new phenotypes. Despite this apparent contradiction, several empirical analyses of living systems, particularly at the molecular scale, have revealed that robustness often facilitates evolvability (Bloom et al., 2006, Ferrada and Wagner, 2008, Hayden et al., 2011, Isalan et al., 2008). A case in point is the cytochrome P450 BM3 complex. In this protein, both thermodynamic stability and mutational robustness — defined as the tendency of a protein to adopt its native structure in the face of mutation — increase the protein’s propensity to evolve novel catalytic functions (Bloom et al., 2006). In other, unrelated enzymes, the ability to evolve new functions is facilitated by the ability of the enzyme’s native functions to tolerate mutations (Aharoni et al., 2005). More generally, the enzymatic diversity of proteins increases with their mutational robustness. This indicates that robust proteins have acquired functional diversity in their evolutionary history — they are more evolvable (Ferrada and Wagner, 2008).

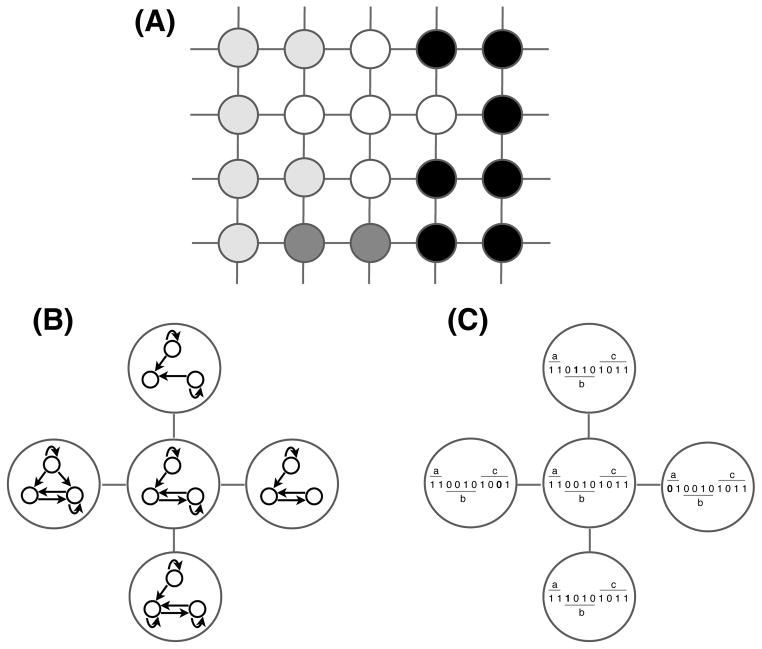

To clarify the relationship between robustness and evolvability, several theoretical models have been proposed (e.g., Newman and Engelhardt (1998), Wagner (2008a), Draghi et al. (2010)). A common feature of these models is the concept of a genotype network (a.k.a. neutral network). In such a network, each node represents a genotype. Edges connect genotypes that share the same phenotype and can be interconverted via single mutational events (Fig. 1A). In the case of RNA secondary structure phenotypes, for example, nodes represent RNA sequences and two nodes are connected if their corresponding sequences confer the same minimum free energy secondary structure, yet differ by a single nucleotide (Schuster et al., 1994). Robust phenotypes have large genotype networks (Wagner, 2008a). Phenotypic robustness confers evolvability because a population can diffuse neutrally throughout the genotype network (Hayden et al., 2011, Huynen et al., 1996) and build up genetic diversity, which allows access to novel phenotypes through non-neutral point mutations into adjacent genotype networks (Wagner, 2008a).

Figure 1.

(A) The space of all possible genotypes can be represented as a network, where vertices correspond to genotypes and edges connect genotypes that can be interconverted through point mutations. A genotype network is a connected subgraph in which each genotype yields the same phenotype (denoted by vertex color). Thus, all point mutations within a genotype network leave the phenotype unchanged. (B) When perturbations correspond to the addition or deletion of regulatory interactions, two RBCs are connected in a genotype network if they share the same gene expression pattern (phenotype), but differ in a single regulatory interaction. (C) When perturbations correspond to changes in the signal-integration logic, two RBCs are connected in a genotype network if they share the same phenotype, but differ in a single bit of their rule vector. This perturbation is analogous to a change in the affinity or position of a transcription factor binding site in the cis-regulatory region that leaves the gene expression pattern unchanged. The genotype networks shown in (B,C) are part of the larger (hypothetical) genotype space shown in (A). The number of neighbors per vertex is intentionally reduced for visual clarity.

Genotype networks have been used to explore the relationship between robustness and evolvability in a variety of biological systems, ranging from the molecular (Schuster et al., 1994, Cowperthwaite et al., 2008, Ferrada and Wagner, 2008, 2010, Wagner, 2008b) to the cellular level (Aldana et al., 2007, Ciliberti et al., 2007a,b, Mihaljev and Drossel, 2009). At the level of proteins and their three-dimensional structure phenotypes, for example, a genotype network is made up of all amino acid sequences that fold into the same structure and that can be reached via single amino acid substitutions (Ferrada and Wagner, 2008). Robust proteins, which are commonly referred to as designable (Li et al., 1996), have large genotype networks and exhibit an enhanced capacity for functional innovation (Ferrada and Wagner, 2008). This is a consequence of the arrangement of protein functions in sequence space, where distant regions of a genotype network provide access to different protein functions (Ferrada and Wagner, 2010).

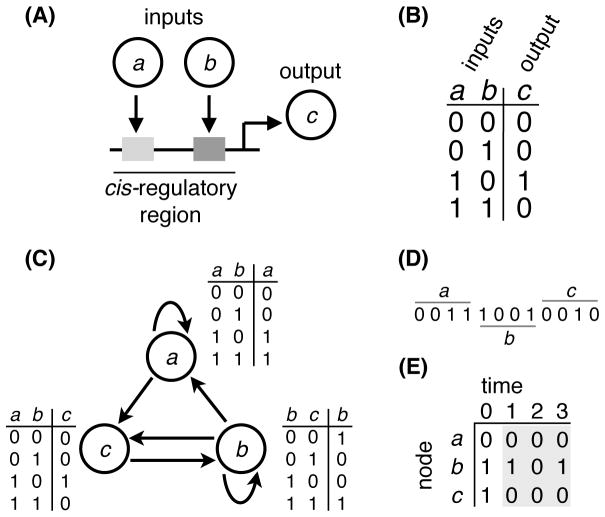

At higher levels of organization, the phenotype of interest is often a gene expression pattern. Such a gene expression pattern is produced by a gene regulatory network, which consists of gene products that activate and inhibit one another’s expression. Gene expression is controlled by a gene’s cis-regulatory region on DNA (Fig. 2A), which can be thought to perform a computation (Fig. 2B), using the regulating gene products as inputs. The regulatory program that encodes this computation is referred to as signal-integration logic. It is specified in the network’s (regulatory) genotype, which comprises the coding regions and the cis-regulatory regions of the network’s genes.

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic of genetic regulation, where gene products a and b serve as regulatory inputs, attaching to their respective binding sites (gray shaded boxes) in the cis-regulatory region of gene c to influence its expression. The input-output function encoded in this regulatory region is called signal-integration logic and can be modeled as (B) a discrete function that explicitly maps all of the 2z input-output combinations of a z-input function. Here, z = 2. (C) All interactions between gene products a, b, and c can be represented as a Random Boolean Circuit (RBC) with N = 3 nodes. In this example circuit, gene product c possesses the same regulatory inputs and signal-integration logic as in (A) to clearly depict how the RBC abstraction captures genetic regulation. (D) The signal-integration logic of every node in the RBC can be simultaneously represented with a single rule vector by concatenating the rightmost columns of each node’s look-up table. (E) The dynamics of the RBC begin with an initial state (e.g., 〈011〉) and eventually settle into an attractor (gray shaded region).

Previous studies of the robustness and evolvability of gene regulatory networks have focused on genetic perturbations that alter network structure by adding or deleting regulatory interactions (Aldana et al., 2007, Ciliberti et al., 2007a,b, Mihaljev and Drossel, 2009). In this case, two gene regulatory networks are connected in a genotype network if they confer the same gene expression pattern, yet differ in a single regulatory interaction (Fig. 1B). The corresponding genotype network is therefore a “network of networks” (Ciliberti et al., 2007b). These analyses have revealed several general properties of the genotypes and phenotypes of gene regulatory networks. First, a genotype’s capacity to bring forth new gene expression phenotypes through genetic change is dependent upon its position in a genotype network (Ciliberti et al., 2007a). Second, the robustness of a genotype to mutation varies across a genotype network, such that some genotypes are vastly more robust than others (Ciliberti et al., 2007b), implying that genotypic robustness is itself an evolvable property (Mihaljev and Drossel, 2009). Third, phenotypes have vast genotype networks that extend throughout the space of all possible genotypes (Ciliberti et al., 2007a, Mihaljev and Drossel, 2009); and fourth, highly robust phenotypes are often highly evolvable (Aldana et al., 2007, Ciliberti et al., 2007a).

While these studies have helped to elucidate the relationship between robustness and evolvability in gene regulatory networks, they are limited by their assumption that genetic perturbations primarily affect network structure. It is well known that the presence or absence of regulatory interactions is not the only determining factor of gene expression patterns (Setty et al., 2003, Mayo et al., 2006, Kaplan et al., 2008, Hunziker et al., 2010). Specifically, by altering the arrangement of promoters and transcription factor binding sites (Fig. 2A, shaded boxes) in a gene’s cis-regulatory region, the signal-integration logic of gene regulation can be dramatically influenced. For example, by rearranging the location of transcription start sites in the promoter region of a reporter gene in the galactose network of Escherichia Coli, 12 of the 16 possible Boolean input-output mappings can be realized (Hunziker et al., 2010). Thus, it is not only the structure of regulatory interactions that affects robustness and evolvability, but also the logic of signal-integration used in the cis-regulatory region of each gene. When genetic perturbations correspond to changes in the signal-integration logic, two gene regulatory networks are connected in the genotype network if they are topologically identical and confer the same gene expression pattern, yet differ in a single element of their signal-integration logic (Fig. 1C). The extent to which genetic perturbations in the signal-integration logic of gene regulatory networks affect robustness and evolvability remains largely unexplored.

We have recently begun to address this open question using computational models of small gene regulatory circuits (Payne and Moore, 2011). These circuits are ideal for such an investigation because their genotype networks are exhaustively enumerable, which allows for a full characterization of the relationship between robustness and evolvability, at both the genotypic and phenotypic scales. In our previous analysis, we focused on the relationship between these properties at the level of the phenotype only, and investigated their influence on a simple, mutation-limited evolutionary process. Here, we extend our previous analysis substantially and provide a detailed characterization of robustness and evolvability at the level of the genotype. We address several fundamental questions concerning the structure of genotype networks in signal-integration space. For instance, what is the distribution of genotypic robustness on a genotype network? Does this distribution differ from the case where genetic perturbations affect circuit structure? Does the position of a genotype in genotype space impact its capacity for evolutionary innovation (i.e., its ability to acquire novel phenotypes via genetic change)? How does the robustness of a phenotype influence the robustness and evolvability of its underlying genotypes? Is there a tradeoff between robustness and evolvability at the level of the phenotype? Are robust phenotypes mutationally biased toward one another? If so, how does this impact mutation-based evolution? After addressing these and other questions, we discuss the implications of our results and present directions for future work.

2 Methods

2.1 Random Boolean Circuits

We use Random Boolean Circuits (RBCs) to model genetic regulation (Kauffman, 1969). RBCs are composed of nodes and directed edges (Fig. 2C). Nodes represent gene products and edges represent regulatory interactions. Two nodes a and c are connected by a directed edge a → c if the expression of gene c is regulated by gene product a. Node states are binary, reflecting the presence (1) or absence (0) of a gene product, and dynamic, such that the state of a node at time t+1 is dependent upon the states of its regulating nodes at time t. This dependence is captured by a look-up table associated with each node, which explicitly maps all possible combinations of regulatory input states to an output expression state. This look-up table is analogous to the signal-integration logic encoded in cis-regulatory regions. The signal-integration logic of all of the nodes in the network can be simultaneously represented using a single rule vector (Fig. 2D).

The dynamics of RBCs occur in discrete time with synchronous updating of node states (Fig. 2E). The dynamics begin at a pre-specified initial state, which can be thought to represent regulatory factors upstream of the circuit (Ciliberti et al., 2007a, Martin and Wagner, 2009). The dynamics then unfold according to the circuit’s structure and signal-integration logic. Since the system is both finite and deterministic, its dynamics eventually settle into an attractor (Kauffman, 1969), which represents the gene expression pattern, and is referred to as the phenotype. We refer to the combination of circuit structure, rule vector, and initial state as an instance of a RBC.

While simple, the Boolean abstraction has proven capable of precisely replicating specific properties of genetic regulation in natural systems. For example, variants of the model have emulated the expression patterns of the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster (Albert and Othmer, 2003), the plant Arabidopsis thaliana (Espinosa-Soto et al., 2004), and the yeast Saccharomyces pombe (Davidich and Bornholdt, 2008). Due to their accuracy in capturing the dynamics of genetic regulation, and because the signal-integration logic of each gene is explicitly represented, RBCs are ideal synthetic systems for investigating the relationship between robustness and evolvability when genetic perturbations correspond to changes in signal-integration logic.

2.2 Dynamical Regimes of RBCs

An important feature of RBCs is that they exhibit three dynamical regimes: ordered, critical, and chaotic (Kauffman, 1969). In the ordered regime, gene expression patterns (i.e., attractors) are relatively insensitive to perturbations, while in the chaotic regime they are highly sensitive. The critical regime delineates these two extremes. For randomly constructed circuits, as considered herein, the transitions between regimes are controlled by two parameters: the average in-degree z and the probability ρ of gene expression (i.e., the probability of observing a 1 in the rule vector). Letting s = 2ρ(1 − ρ)z, the RBC lies in the ordered regime when s < 1, the critical regime when s = 1, and the chaotic regime when s > 1 (Aldana and Cluzel, 2003, Schmulevich and Kauffman, 2004). When there is an equal probability of observing a 0 or a 1 in the rule vector (ρ = 0.5) the dynamical regime is determined solely by the average in-degree, with z < 2 yielding the ordered regime, z = 2 the critical regime, and z > 2 the chaotic regime. In this study, we use ρ = 0.5 and a fixed number of inputs per node z ∈ {1, 2, 3}.

2.3 Genotype Networks

We refer to the signal-integration logic of a RBC, as represented by its rule vector (Fig. 2D), as the circuit’s genotype. There are a total of 2L unique genotypes for a given combination of circuit structure and initial state, where L = N2z. We refer to this set of genotypes as the genotype space, or equivalently, as the signal-integration space. For the RBCs considered here, the size of the genotype space ranges from 26 for the ordered regime to 224 for the chaotic regime.

These genotypes map to a significantly smaller set of phenotypes. This high level of redundancy is a general feature of RBCs, and can be formalized using a genotype network, in which rule vectors are represented as nodes, and edges connect rule vectors that differ by a single bit, yet yield the same gene expression pattern (i.e., phenotype). Thus, we define a neutral point mutation as a single change to an element of the genotype that does not lead to a change in phenotype. Such a mutation can be thought of as a change in the affinity or position of a transcription factor binding site in the cis-regulatory region that leaves the gene expression pattern unchanged. We characterize genotype networks using an exhaustive breadth-first search, thus discovering all genotypes that yield the same phenotype and are accessible via neutral point mutations, starting from the original genotype of an RBC instance. While it may be possible that a phenotype is comprised of multiple disconnected genotype networks, our analysis is focused on the connected component of the genotype network in which the RBC instance resides, which we refer to as the focal genotype network.

2.4 Observable Quantities

Several definitions of robustness and evolvability have been proposed, at both the genotypic and phenotypic scales (Aldana et al., 2007, Wagner, 2008b, Mihaljev and Drossel, 2009, Draghi et al., 2010). Here, we define these terms as they are used in this study. Where appropriate, we use superscripts to indicate whether a variable or function pertains to the genotypic (g) or phenotypic (p) scale.

The quantity vxPyP captures the number of unique non-neutral point mutations to genotypes in the focal genotype network of phenotype xp that lead to genotypes in a genotype network of phenotype yp. We call phenotypes xp and yp adjacent if vxPyP> 0. By enumerating all of the genotype networks that are adjacent to the focal genotype network of phenotype xp, we capture the mutational biases between adjacent phenotypes; that is, we capture the propensity with which the genotypes on one genotype network mutate into the genotypes on adjacent genotype networks. Our analysis therefore completely characterizes both the focal genotype network and its adjacent genotype networks.

2.4.1 Robustness

We define the genotypic robustness Rg(xg) of a genotype xg as the proportion of its L possible point mutations that do not lead to a change in phenotype. This quantity is normalized by L to provide a measure that is independent of rule vector length. We use as a proxy for phenotypic robustness Rp(xp) the proportion of signal-integration space that is occupied by the focal genotype network of phenotype xp. This proxy captures the fraction of all genotypes that yield the same phenotype and that can also be accessed via neutral point mutation from the rule vector of an RBC instance. This quantity is normalized by 2L to provide a measure that is independent of the size of genotype space. Thus, we consider phenotypic robustness to be the fractional size of the phenotype’s underlying focal genotype network.

2.4.2 Evolvability

Genotypic evolvability Eg(xg) is defined as the number of unique phenotypes that can be reached through individual non-neutral point mutations to genotype xg. We define phenotypic evolvability using two metrics. The first Ep(xp) is simply the number of phenotypes that can be accessed through non-neutral point mutations from the focal genotype network of phenotype xp (Wagner, 2008b). The second ξp(xp) captures the mutational biases that exist between the focal genotype network of phenotype xp and its adjacent genotype networks (Cowperthwaite et al., 2008). Letting

| (1) |

denote the fraction of non-neutral point mutations to genotypes on the focal genotype network of phenotype xp that result in genotypes of phenotype yp, we define the evolvability ξp(xp) of phenotype xp as

| (2) |

Since captures the probability that two randomly chosen non-neutral point mutations to genotypes on the focal genotype network of phenotype xp result in genotypes with identical phenotypes, its complement ξp(xp) captures the probability that these same mutations result in genotypes with distinct phenotypes. This metric takes on high values when a phenotype is adjacent to many other phenotypes and its non-neutral point mutations are uniformly divided amongst these phenotypes. The metric takes on low values when a phenotype is adjacent to only a few other phenotypes and its non-neutral point mutations are biased toward a subset of these phenotypes.

2.4.3 Accessibility

In addition to measuring phenotypic evolvability, we also consider phenotypic accessibility

| (3) |

which captures the propensity to mutate into the focal genotype network of phenotype xp (Cowperthwaite et al., 2008). This metric takes on high values if the phenotypes adjacent to phenotype xp are mutationally biased toward xp and low values otherwise.

2.4.4 Adjacent Robustness

We measure the robustness of all phenotypes that are adjacent to the focal genotype network of phenotype xp, in proportion to the probability that these phenotypes are encountered through a randomly chosen, non-neutral point mutation from the focal genotype network of phenotype xp (Cowperthwaite et al., 2008). We refer to this quantity as adjacent robustness,

| (4) |

This metric takes on high values when a phenotype is mutationally biased toward robust phenotypes and low values otherwise.

2.4.5 Distance and Diversity

The genotypic distance Dg between two genotypes xg and yg is given by the normalized Hamming distance

| (5) |

where if genotypes xg and yg differ at location i and otherwise. This quantity is normalized by L to provide a measure that is independent of rule vector length.

Following Ciliberti et al. (2007a), the diversity Fp of the sets of phenotypes P(xg) and P(yg) that are accessible through individual non-neutral point mutations to genotypes xg and yg of the same genotype network, is calculated as

| (6) |

This measure captures the proportion of all phenotypes in P(xg) and P(yg) that are unique to either P(xg) or P(yg). We refer to this measure as the diversity of adjacent phenotypes and consider it in the context of genotypic distance. For example, if the genotypic distance Dg(xg, yg) between genotypes xg and yg is large, but the diversity of adjacent phenotypes Fp(P(xg), P(yg)) is small, then the position of a genotype in genotype space has little influence on which phenotypes are accessible via non-neutral point mutation. In contrast, if both Dg(xg, yg) and Fp(P(xg), P(yg)) are large, then the position of a genotype in genotype space has a strong influence on which phenotypes are accessible via non-neutral point mutation. Note that xg and yg can be separated by any distance, so long as they reside on the same genotype network. Note also that the phenotypes in P(xg) need not be adjacent to the phenotypes in P(yg).

2.5 Simulation Details and Data Analysis

For all RBC instances, the rule vector and initial state are generated at random with ρ = 0.5. The circuit structure is also generated at random, but subject to the constraint that each node has exactly z inputs. Self-loops are permitted, mimicking autoregulation. We separately consider RBCs in the ordered, critical, and chaotic regimes by setting z = 1, 2, 3, respectively. The initial state and circuit structure are held fixed for each RBC instance. To ensure that all of the genotype networks considered in this study are amenable to exhaustive enumeration, we restrict our attention to RBCs with N = 3 nodes. While these RBCs are small, sensitivity analysis (Derrida and Pomeau, 1986) confirms that they exhibit the same dynamical regimes as larger networks, albeit with shorter attractors. To assess the strength and significance of the trends in our data, we employ Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

3 Results

3.1 Characteristics of Genotype Networks

To describe the structure of signal-integration space in RBCs, we randomly generate 2500 RBC instances for each dynamical regime and exhaustively characterize the focal genotype networks of their corresponding phenotypes, and the genotype networks of all adjacent phenotypes.

As the dynamical regime shifts from ordered to chaotic, the mean, variance, and maximum of the distributions of genotypic robustness (Fig. 3A–C) and genotypic evolvability (Fig. 3D–F) increase. For example, mean genotypic robustness increases by 72% and mean genotypic evolvability increases by 114% as the dynamical regime transitions from ordered to chaotic. Genotypic evolvability and genotypic robustness are inversely correlated (Fig. 3G), highlighting the fundamental tradeoff between these two quantities. The strength of correlation is virtually indistinguishable between dynamical regimes (z = 1 : r = −0.97, p ≪ 0.001; z = 2 : r = −0.98, p ≪ 0.001; z = 3 : r = −0.98, p ≪ 0.001), but the slopes of these inverse relationships vary significantly. For instance, increasing genotypic robustness from 0.4 to 0.5 results in a 28% reduction in genotypic evolvability for chaotic RBCs, but only an 18% reduction for ordered RBCs.

Figure 3.

Distributions of (A–C) genotypic robustness Rg and (D–F) genotypic evolvability Eg for each of the three dynamical regimes: (A,D) ordered (z = 1), (B,E) critical (z = 2), and (C,F) chaotic (z = 3). Each distribution comprises data from 2500 genotype networks. (G) Average genotypic evolvability as a function of average genotypic robustness , for each of the three dynamical regimes. Each data point represents an average across all genotypes in a genotype network.

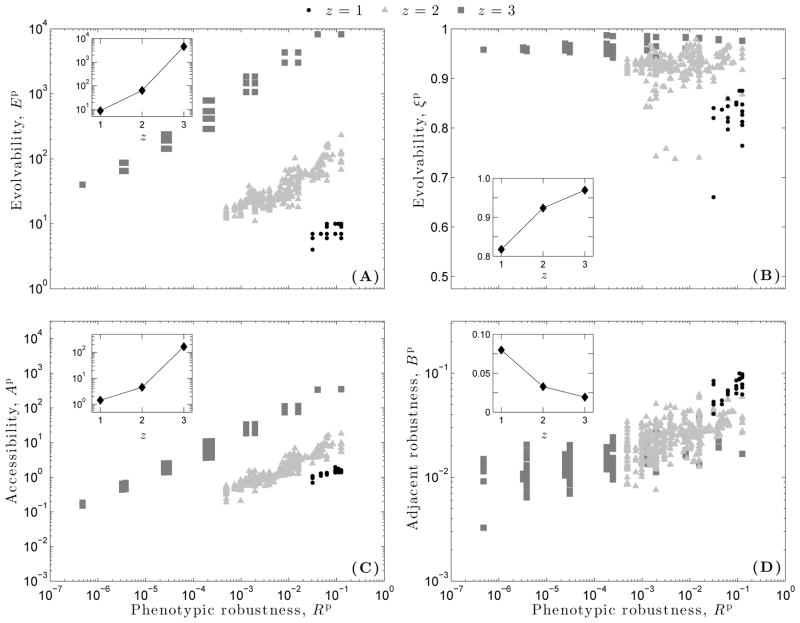

The range of phenotypic robustness Rp varies with dynamical regime, with ordered RBCs spanning the smallest range (3.12×10−2 ≤ Rp ≤ 1.25×10−1), critical RBCs spanning an intermediate range (4.88×10−4 ≤ Rp ≤ 1.25 × 10−1), and chaotic RBCs spanning the largest range (4.77 × 10−7 ≤ Rp ≤ 1.25 × 10−1). The maximum value of phenotypic robustness is independent of dynamical regime, and corresponds to the case where the initial state is identical to the attractor, which thus comprises only a single state (i.e., it is a fixed-point attractor). In this case, there are no transient dynamics and each vertex is exposed to only a single input value during the attractor, which means that only a single entry of each of the N look-up tables is used. This implies that only N bits of the rule vector are accessed during the RBC’s dynamics, leaving L − N bits unused. Thus, the corresponding genotype network is of size 2L−N, with phenotypic robustness . The average phenotypic robustness decreases from the ordered (Rp = 9.57 × 10−2) to the critical (Rp = 4.12 × 10−2) to the chaotic (Rp = 3.02 × 10−2) regime.

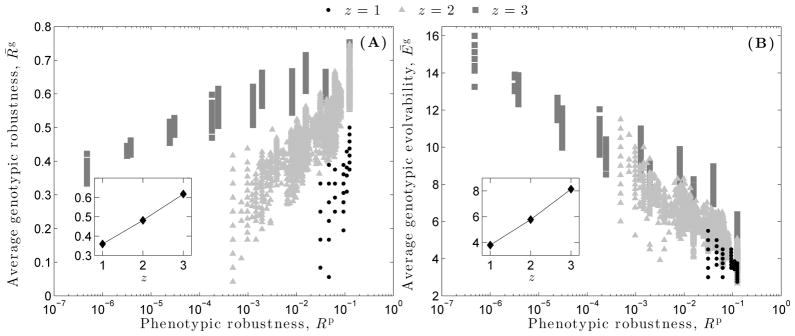

Average genotypic robustness is positively correlated (Fig. 4A; z = 1 : r = 0.82, p ≪ 0.01; z = 2 : r = 0.88, p ≪ 0.01; z = 3 : r = 0.81, p ≪ 0.01), and average genotypic evolvability negatively correlated (Fig. 4B; z = 1 : r = −0.83, p ≪ 0.01; z = 2 : r = −0.88, p ≪ 0.01; z = 3 : r = −0.81, p ≪ 0.01), with phenotypic robustness. The genotypes that map to a given phenotype therefore become more robust and less evolvable as that phenotype becomes more robust. Averaging genotypic robustness and genotypic evolvability across all 2500 RBC instances per dynamical regime reveals a linear increase in both quantities as z increases (Fig. 4, insets). Thus, the genotypes of chaotic RBCs are simultaneously more robust and more evolvable than the genotypes of critical or ordered RBCs, on average.

Figure 4.

(A) Average genotypic robustness and (B) average genotypic evolvability as a function of phenotypic robustness Rp, for each of the three dynamical regimes: ordered (z = 1), critical (z = 2), and chaotic (z = 3). The insets depict the corresponding averages across all 2500 genotype networks, as a function of z. Lines are provided as a guide for the eye.

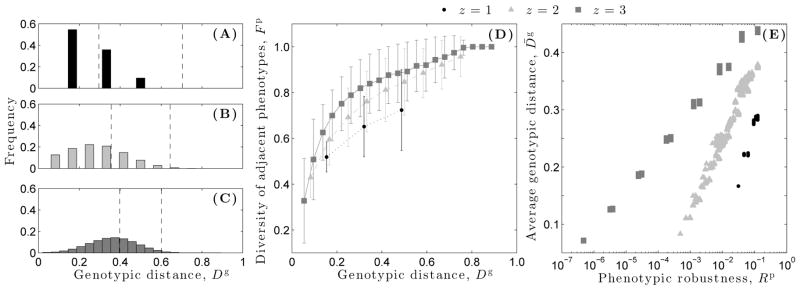

To determine the distributions of genotypic distance between pairs of genotypes, we randomly sample 10,000 pairs of genotypes from each of the 2500 genotype networks per dynamical regime (Fig. 5A–C). We then compare these distributions to their corresponding null distributions, which are computed by randomly sampling 25 million pairs of genotypes from the entirety of genotype space (i.e., without regard to phenotype) (Fig. 5A–C, vertical lines). The average genotypic distance between randomly sampled pairs of genotypes from focal genotype networks increases from the ordered ( ) to the critical ( ) to the chaotic ( ) regime. However, these averages are always significantly less than the averages of the corresponding null distributions (p ≪ 0.001 for all z, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), indicating that the connected components of genotype networks of signal-integration logic are constrained to specific regions of genotype space.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the genotypic distance Dg between randomly sampled pairs of genotypes from focal genotype networks in each of the three dynamical regimes: (A) ordered (z = 1), (B) critical (z = 2), and (C) chaotic (z = 3). The dashed vertical lines represent one standard deviation from the mean of the corresponding null distribution (see text). (D) Diversity of adjacent phenotypes Fp as a function of genotypic distance Dg. Data are offset in the horizontal dimension for visual clarity. Error bars denote one standard deviation from the mean. (E) Average genotypic distance per genotype network, as a function of phenotypic robustness Rp.

To understand how the position of a genotype in genotype space impacts the variety of phenotypes it may access via non-neutral mutation, we consider the diversity of adjacent phenotypes Fp as a function of genotypic distance Dg (Fig. 5D). For all three dynamical regimes, the diversity of adjacent phenotypes increases as the distance between two genotypes on the same connected components of a genotype network increases. In the critical regime, for example, 43% of the phenotypes found within the 1-neighborhoods of genotypes separated by a distance of D = 0.08 are unique; for D = 0.75, 95% are unique. Thus, the greater the distance between two genotypes, the greater the difference between the two sets of phenotypes that may be encountered via non-neutral mutation. Strikingly, 100% of the phenotypes found within the 1-neighborhoods of genotypes separated by a distance D > 0.8 are unique in the chaotic regime. As expected, the average genotypic distance between randomly sampled genotypes increases as phenotypic robustness Rp increases (Fig. 5E), supporting the intuitive notion that larger genotype networks extend farther throughout genotype space than smaller genotype networks.

Phenotypic evolvability Ep and phenotypic robustness Rp are positively correlated (Fig. 6A), and the strength of correlation increases from the ordered (r = 0.65, p ≪ 0.01) to the critical (r = 0.89, p ≪ 0.01) to the chaotic (r = 0.98, p ≪ 0.01) regime. This indicates that, in this system, no trade-off exists between phenotypic robustness and the number of phenotypes accessible via non-neutral point mutations; the more robust the phenotype, the higher its evolvability Ep. Average phenotypic evolvability increases faster than linearly with increasing z, indicating a rapid increase in the number of adjacent phenotypes as the dynamical regime shifts from ordered to chaotic (Fig. 6A, inset).

Figure 6.

Phenotypic evolvability (A) Ep, (B) ξp, (C) accessibility Ap, and (D) adjacent robustness Bp as a function of phenotypic robustness Rp for each of the three dynamical regimes: ordered (z = 1), critical (z = 2), and chaotic (z = 3). Each data point represents one of 2500 RBC instances for each dynamical regime. The insets depict the corresponding averages, as a function of z. Lines are provided as a guide for the eye.

When mutational biases between adjacent phenotypes are taken into account using ξp, a slightly different relationship is observed between phenotypic evolvability and phenotypic robustness (Fig. 6B). RBCs in the ordered regime exhibit a weak and insignificant correlation between ξp and Rp (r = 0.02, p = 0.41). In contrast, RBCs in the critical and chaotic regimes exhibit weak, but significant correlations, with the strength of correlation increasing from the critical (r = 0.09, p ≪ 0.01) to the chaotic regime (r = 0.42, p ≪ 0.01). The average evolvability increases approximately linearly as z increases (Fig. 6B, inset). Thus, the average probability that two randomly chosen, non-neutral point mutations lead to distinct phenotypes is only ≈ 15% higher in chaotic RBCs than in ordered RBCs, despite the four order-of-magnitude difference in the absolute number of adjacent phenotypes (Fig. 6A, inset).

Phenotypic accessibility Ap and phenotypic robustness Rp are positively correlated (Fig. 6C), with the strength of correlation again increasing from the ordered (r = 0.81, p ≪ 0.01) to the critical (r = 0.93, p ≪ 0.01) to the chaotic (r = 0.98, p ≪ 0.01) regimes. This implies that, for all three dynamical regimes, random point mutations are more likely to lead to robust phenotypes than to non-robust phenotypes. Average accessibility increases faster than linearly as z increases (Fig. 6C, inset), indicating a rapid increase in the relative ease with which phenotypes are found by random mutation as the dynamical regime shifts from ordered to chaotic.

Adjacent robustness Bp and phenotypic robustness Rp are positively correlated, with the strength of correlation decreasing from the ordered (r = 0.89, p ≪ 0.01) to the critical (r = 0.64, p ≪ 0.01) to the chaotic regimes (r = 0.35, p ≪ 0.01). This implies that non-neutral point mutations to genotypes within robust phenotypes often lead to other robust phenotypes, but that the strength of this tendency weakens as RBCs approach the chaotic regime. The average adjacent robustness decreases approximately linearly as z increases (Fig. 6D, inset), indicating that the expected robustness of a phenotype encountered via non-neutral point mutation decreases as the dynamical regime shifts from ordered to chaotic.

Taken together, these results suggest that a series of random point mutations will tend toward phenotypes of increased robustness (Fig. 6D) and correspondingly increased evolvability (Fig. 6A,B). Further, the ease with which such a blind evolutionary process identifies an arbitrary phenotype should increase with that phenotype’s robustness (Fig. 6C) and as the dynamical regime shifts from ordered to critical to chaotic (Fig. 6C, inset).

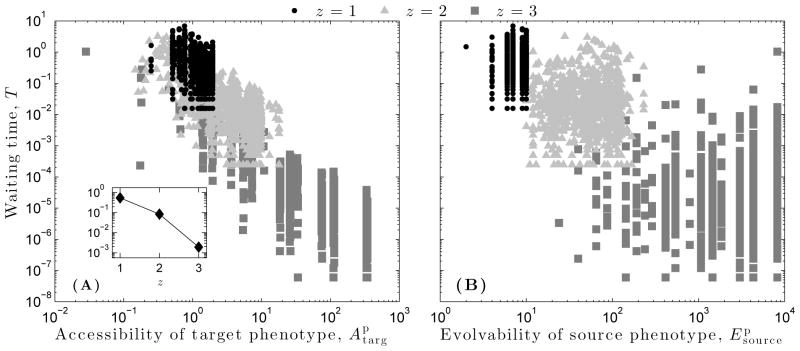

3.2 Random Walks Through Signal-Integration Space

To investigate how phenotypic robustness, evolvability, and accessibility influence blind, mutation-based evolution, we conduct an ensemble of random walks. For each dynamical regime, we randomly generate 1000 RBC instances and identify the phenotype of each instance as a source phenotype. For each instance, we then sample the genotype space at random until we discover a genotype that yields a different phenotype from the source phenotype, and we identify this as the target phenotype. For each pair of source and target phenotypes, we then perform a random walk, starting from the instance’s genotype and ending when the random walk reaches any genotype in the target phenotype. Each step in the random walk corresponds to a single point mutation to the genotype. We record the number of steps S required to reach the target phenotype, which we normalize by the size of the signal-integration space 2L, and refer to as the waiting time T = S/2L.

Waiting time T decreases faster than linearly as z increases (Fig. 7A, inset). For all three dynamical regimes, waiting time is strongly negatively correlated with the accessibility A of the target phenotype (Fig. 7A), and the strength of correlation increases from the ordered (r = −0.41, p ≪ 0.01) to the critical (r = −0.67, p ≪ 0.01) to the chaotic (r = −0.82, p ≪ 0.01) regime. In contrast, the correlation between waiting time T and the evolvability Ep of the source phenotype is weak and insignificant (z = 1 : r = −0.03, p = 0.38; z = 2 : r = 0.01, p = 0.82; z = 3 : r = −0.02, p = 0.56) (Fig. 7B). We observed similarly weak and insignificant correlations between waiting time T and other characteristics of the source phenotype, such as ξp, Ap, and Bp (data not shown). These results indicate that the time required for a blind evolutionary search to identify a target phenotype is independent of the phenotypic properties of the starting point and solely dependent upon the phenotypic properties of the target.

Figure 7.

Waiting time of a random walk T = S/2L as a function of (A) the target phenotype’s accessibility and (B) the source phenotype’s evolvability , for each of the three dynamical regimes: ordered (z = 1), critical (z = 2), and chaotic (z = 3). The inset in (A) depicts the average waiting time T as a function of z. Lines are provided as a guide for the eye.

4 Discussion

In this study, we have extended our previous analysis (Payne and Moore, 2011) of genotype networks in the signal-integration space of Random Boolean Circuits (RBCs). While our earlier work was focused exclusively on the properties of phenotypes, we now additionally provide a detailed description of the properties of genotypes. Specifically, we have characterized the distributions of genotypic robustness Rg (Fig. 3A–C) and genotypic evolvability Eg (Fig. 3D–F), revealing distributions that are skewed toward genotypes of high robustness and low evolvability, which increase in both mean and variance as the dynamical regime shifts toward chaos. This variability implies that genotypic robustness and genotypic evolvability are themselves evolvable properties in RBCs, that by gradually altering signal-integration logic via point mutation, an evolutionary process can navigate through signal-integration space toward areas of either high genotypic robustness or high genotypic evolvability, without phenotypic modification.

When genetic perturbations correspond to changes in circuit structure, rather than to changes in signal-integration logic, the distribution of genotypic robustness is skewed toward genotypes of low robustness (Ciliberti et al., 2007b). This result contrasts with our observations, and underscores the sensitivity of the structure of genotype networks to the form of genetic perturbation under consideration. Regardless of the form of genetic perturbation, it is not possible to simultaneously maximize genotypic robustness and genotypic evolvability (Fig. 3G), due to the inherent tradeoff between these properties (Wagner, 2008b).

We found a positive correlation between average genotypic robustness and phenotypic robustness Rp (Fig. 4A), an intuitive observation given that the latter quantity is commonly defined via the former (Wagner, 2008b). In contrast, average genotypic evolvability was negatively correlated with phenotypic robustness Rp (Fig. 4B), indicating that the individual genotypes that make up robust phenotypes have a reduced capacity for innovation, relative to the genotypes of less robust phenotypes. Both the average genotypic robustness and the average genotypic evolvability increased as the dynamical regime shifted from ordered to chaotic (Fig. 4, insets).

To understand how a genotype’s position in signal-integration space influences its capacity for innovation, we analyzed the relationship between the genotypic distance Dg of randomly sampled pairs of genotypes on the same genotype network, and the diversity of phenotypes Fp accessible via non-neutral point mutation from these genotypes. We found a monotonic increase in Fp across the full range of genotypic distances observed for each dynamical regime. This results contrasts again with observations made by Ciliberti et al. (2007a), who only found a strong statistical association between these quantities for low genotypic distance (Dg ≲ 0.2). Thus, large distances between genotypes in signal-integration space may facilitate access to a greater diversity of phenotypes than the same genotypic distances in the space of circuit structures.

We found a positive correlation between phenotypic robustness Rp and phenotypic evolvability, as measured by either the absolute number of adjacent phenotypes Ep (Fig. 6A) or by the probability that two non-neutral point mutations lead to distinct phenotypes ξp (Fig. 6B). Our results corroborate the observation made in previous studies that the phenotypes of gene regulatory networks can simultaneously exhibit robustness and evolvability (Aldana et al., 2007, Ciliberti et al., 2007a,b). Further, our analyses extend these previous studies by providing an explicit description of this relationship and by considering genetic perturbations that alter the signal-integration logic encoded in cis-regulatory regions, instead of genetic perturbations that alter circuit structure.

We also found a positive correlation between phenotypic robustness Rp and phenotypic accessibility Ap (Fig. 6C), a measure that captures the relative ease with which a phenotype can be identified by mutation-based evolution. This result supports the intuitive notion that phenotypes formed by many genotypes are easier to find in blind evolutionary searches than phenotypes formed by few genotypes. In addition, robust phenotypes are mutationally biased toward other robust phenotypes (Fig. 6D), indicating that blind evolutionary searches should encounter, at least on average, highly robust phenotypes. This observation corroborates recent observations made in RNA systems (Jörg et al., 2008), where biological RNA structures were shown to have significantly larger genotype networks than random RNA structures.

To understand how phenotypic robustness, evolvability, and accessibility in signal-integration space influence mutation-based evolution, we considered an ensemble of random walks between pairs of source and target phenotypes. We found that the number of random mutations required to reach the target phenotype was entirely dependent upon its accessibility (Fig. 7A) and independent of any properties of the source phenotype (e.g., Fig. 7B). This suggests that a random walk through signal-integration space quickly loses any memory of its starting location. Consequently, extant evolvability metrics cannot be expected to predict the duration of a random walk between phenotypes. To overcome this issue, future work will seek to develop new phenotypic evolvability metrics that take into consideration the global structure of genotype space, as opposed to only considering the immediate adjacency of genotype networks.

Most of our results are consistent with those made in RNA systems (Cowperthwaite et al., 2008, Wagner, 2008b). However, there is one difference worth emphasizing: the correlation between phenotypic robustness Rp and phenotypic evolvability ξp is negative in RNA (Cowperthwaite et al., 2008). Since the relationship between Rp and adjacent robustness Bp is positive in RNA, Cowperthwaite et al. (2008) concluded that robust phenotypes act as “evolutionary traps” (but, see Wagner (2008b)). That is, random mutation may tend toward phenotypes of higher robustness, which in turn may be less evolvable by this criterion, and therefore slow down evolutionary search. Since we observed a positive correlation between (i) Rp and ξp and between (ii) Rp and Bp, we conclude that robust phenotypes in the signal-integration space of RBCs are not evolutionary traps, but instead may facilitate the discovery of novel phenotypes. Such contrasts between model systems underscores the fact that the relationships between robustness, evolvability, and accessibility are system dependent.

Phenotypic evolvability increased monotonically as z increased (Fig. 6A,B, insets) and the maximum achievable robustness was independent of z (Rmax = 2−N). Taken together, these results indicate that robustness and evolvability can be simultaneously maximized in chaotic RBCs. This result contrasts with previous analysis (Aldana et al., 2007), which found robustness and evolvability to be simultaneously maximized in critical RBCs. This discrepancy can be understood by considering the two primary differences between the analyses. First, Aldana et al. (2007) focused on genetic perturbations that altered circuit structure (and consequently, in some cases, signal-integration logic) while we focused solely on genetic perturbations that altered signal-integration logic. Second, and of greater importance, the measures of robustness and evolvability considered by Aldana et al. (2007) were not based on genotype networks. Instead, robustness was defined as the ability of a single mutated genotype to maintain the phenotypic landscape (i.e., the set of all phenotypes observed across all possible initial states), and evolvability was defined as the capacity of the mutated genotype to expand the phenotypic landscape (i.e., add new phenotypes to the set of existing phenotypes). Thus, the definitions of robustness and evolvability used by Aldana et al. (2007) differed from ours, and were focused solely on the level of individual genotypes and their immediate mutational neighbors. While these definitions are reasonable and insightful, our departure from their use precludes any direct comparison between the two studies. That said, our observation that the robustness and evolvability of chaotic RBCs, at both the genotypic and phenotypic scales, are higher than that of critical or ordered RBCs should be interpreted with caution. For all dynamical regimes, robustness is maximal for fixed point attractors, and these occur with decreasing frequency as the dynamical regime transitions from order to chaos (i.e., as z increases). Thus, while it is only possible to simultaneously observe maximal robustness and maximal evolvability in chaotic RBCs, this case represents the exception rather than the rule.

Future work will seek to understand how evolution navigates signal-integration space. Is it possible for mutation and selection to identify the high-robustness, high-evolvability phenotypes of chaotic RBCs? If so, can they out-compete critical and ordered RBCs in static (Oikonomou and Cluzel, 2006) or dynamic (Greenbury et al., 2010) environments? How are these evolutionary outcomes affected by mutation rate (Wilke et al., 2001) or recombination (Martin and Wagner, 2009)? Future research will also focus on larger systems, moving from an analysis of small circuits to large networks. To accomplish this, Monte Carlo sampling methods will be required (Jörg et al., 2008), as the increased size of the signal-integration space will prohibit the exhaustive enumeration of genotype networks. In addition, future work will seek to understand both the influence of canalyzing functions (Kauffman et al., 2004) and the probability of gene expression on the size and structure of genotype networks. These directions, among others (e.g., Pechenick et al. (2012)), will lead to a more thorough theoretical understanding of how the genetic malleability of cis-regulatory DNA can influence evolutionary processes.

Acknowledgments

J.L.P. was supported by a Collaborative Research Travel Grant from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and an International Research Fellowship from the National Science Foundation. J.H.M. was supported by NIH grants LM010098, LM009012, and AI59694. A.W. acknowledges support through Swiss National Science Foundation grants 315230-129708, as well as through the YeastX project of SystemsX.ch, and the University Priority Research Program in Systems Biology at the University of Zurich.

Contributor Information

Joshua L. Payne, Email: joshua.payne@ieu.uzh.ch, University of Zurich, Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, Building Y27-J-48, Winterhurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zurich, Switzerland, phone:+41-44-635-6147

Jason H. Moore, Email: jason.h.moore@dartmouth.edu, Dartmouth College, Computational Genetics Laboratory, HB 7937, One Medical Center Drive, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, 03756, USA, phone: 1-603-653-9939

Andreas Wagner, Email: andreas.wagner@ieu.uzh.ch, University of Zurich, Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Environmental Studies, Building Y27-J-54, Winterhurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zurich, Switzerland and The Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, NM, 87501, USA, phone:+41-44-635-6142.

References

- Aharoni A, Gaidukov L, Khersonsky O, Gould SM, Roodveldt C, Tawfik DS. The ‘evolvability’ of promiscuous protein functions. Nature Genetics. 2005;37:73–76. doi: 10.1038/ng1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert R, Othmer HG. The topology of the regulatory interactions predicts the expression pattern of the segment polarity genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2003;223:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00035-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldana M, Balleza E, Kauffman S, Resendiz O. Robustness and evolvability in genetic regulatory networks. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2007;245:433–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldana M, Cluzel P. A natural class of robust networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences. 2003;100:8710–8714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1536783100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JD, Labthavikul ST, Otey CR, Arnold FH. Protein stability promotes evolvability. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences. 2006;103:5869–5874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510098103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberti S, Martin OC, Wagner A. Innovation and robustness in complex regulatory gene networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences. 2007a;104:13591–13596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705396104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliberti S, Martin OC, Wagner A. Robustness can evolve gradually in complex regulatory gene networks with varying topology. PLoS Computational Biology. 2007b;3:e15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowperthwaite MC, Economo EP, Harcombe WR, Miller EL, Meyers LA. The ascent of the abundant: how mutational networks constrain evolution. PLoS Computational Biology. 2008;4:e10000110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidich MI, Bornholdt S. Boolean network model predicts cell cycle sequence of fission yeast. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrida B, Pomeau Y. Random networks of automata: a simple annealed approximation. Europhysics Letters. 1986;1:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Draghi JA, Parsons TL, Wagner GP, Plotkin JB. Mutational robustness can facilitate adaptation. Nature. 2010;463:353–355. doi: 10.1038/nature08694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa-Soto C, Padilla-Longoria P, Alvarez-Buylla ER. A gene regulatory network model for cell-fate determination during Arabidopsis thaliana flower development that is robust and recovers experimental gene expression profiles. The Plant Cell. 2004;16:2923–2939. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.021725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrada E, Wagner A. Protein robustness promotes evolutionary innovations on large evolutionary time-scales. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B. 2008;275:1595–1602. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrada E, Wagner A. Evolutionary innovations and the organization of protein functions in genotype space. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e14172. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbury SF, Johnston IG, Smith MA, Doye JPK, Louis AA. The effect of scale-free topology on the robustness and evolvability of genetic regulatory networks. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2010;267:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden E, Ferrada E, Wagner A. Cryptic genetic variation promotes rapid evolutionary adaptation in an RNA enzyme. Nature. 2011;474:92–95. doi: 10.1038/nature10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunziker A, Tuboly C, Horváth P, Krishna S, Semsey S. Genetic flexibility of regulatory networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences. 2010;107:12998–13003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915003107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynen MA, Stadler PF, Fontana W. Smoothness within ruggedness: The role of neutrality in adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences. 1996;93:397–401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isalan M, Lemerle C, Michalodimitrakis K, Horn C, Beltrao P, Raineri E, Garriga-Canut M, Serrano L. Evolvability and hierarchy in rewired bacterial gene networks. Nature. 2008;452:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature06847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jörg T, Martin OC, Wagner A. Neutral network sizes of biological RNA molecules can be computed and are not atypically small. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan S, Bren A, Zaslaver A, Dekel E, Alon U. Diverse two-dimensional input functions control bacterial sugar genes. Molecular Cell. 2008;29:786–792. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman SA. Metabolic stability and epigenesis in randomly constructed genetic nets. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1969;22:437–467. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(69)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman SA, Peterson C, Samuelsson B, Troein C. Genetic networks with canalyzing Boolean rules are always stable. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:17102–17107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407783101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Helling R, Tang C, Wingreen N. Emergence of preferred structures in a simple model of protein folding. Science. 1996;273:666–669. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin OC, Wagner A. Effects of recombination on complex regulatory circuits. Genetics. 2009;138:673–684. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.104174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo AE, Setty Y, Shavit S, Zaslaver A, Alon U. Plasticity of the cis-regulatory input function of a gene. PLoS Biology. 2006;4:e45. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaljev T, Drossel B. Evolution of a population of random Boolean networks. European Physics Journal B. 2009;67:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Newman M, Engelhardt R. Effects of selective neutrality on the evolution of molecular species. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B. 1998;265:1333–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomou P, Cluzel P. Effects of topology on network evolution. Nature Physics. 2006;2:532–536. [Google Scholar]

- Payne JL, Moore JH. Robustness, evolvability, and accessibility in the signal-integration space of gene regulatory circuits. Proceedings of the European Conference on Artificial Life, ECAL-2011. 2011:662–669. [Google Scholar]

- Pechenick DA, Payne JL, Moore JH. The influence of assortativity on the robustness of signal-integration logic in gene regulatory networks. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2012;296:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmulevich I, Kauffman SA. Activities and sensitivities in Boolean network models. Physical Review Letters. 2004;93:048701. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.048701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster P, Fontana W, Stadler PF, Hofacker IL. From sequences to shapes and back: a case study in RNA secondary structures. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B. 1994;255:279–284. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setty Y, Mayo A, Surette M, Alon U. Detailed map of a cis-regulatory input function. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences. 2003;100:7702–7707. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1230759100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. Robustness and Evolvability in Living Systems. Princeton University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. Neutralism and selectionism: a network-based reconciliation. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2008a;9:965–974. doi: 10.1038/nrg2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner A. Robustness and evolvability: a paradox resolved. Proceedings of the Royal Society London B. 2008b;275:91–100. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke CO, Wang JL, Ofria C, Lenski RE, Adami C. Evolution of digital organisms at high mutation rates leads to survival of the flattest. Nature. 2001;412:331–333. doi: 10.1038/35085569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]