Abstract

This review focuses on synaptic depression at sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses in the defensive withdrawal circuit of Aplysia as a model system for analysis of molecular mechanisms of sensory gating and habituation. We address the following topics:

Of various possible mechanisms that might underlie depression at these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses in Aplysia, historically the most widely-accepted explanation has been depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles. Depletion is also believed to account for synaptic depression at long interstimulus intervals in a variety of other systems.

Multiple lines of evidence now indicate that vesicle depletion is not an important contributing mechanism to synaptic depression at Aplysia sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses. More generally, it appears that vesicle depletion does not contribute substantially to depression that occurs with those stimulus patterns that are typically used in studying behavioral habituation.

Recent evidence suggests that at these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses in Aplysia, synaptic depression is mediated by an activity-dependent, but release-independent, switching of individual release sites to a silent state. This switching off of release sites is initiated by Ca2+ influx during individual action potentials. We discuss signaling proteins that may be regulated by Ca2+ during the silencing of release sites that underlies synaptic depression.

Bursts of 2–4 action potentials in presynaptic sensory neurons in Aplysia prevent the switching off of release sites via a Ca2+- and protein kinase C (PKC)-dependent mechanism: “burst-dependent protection” from synaptic depression.

This Ca2+- and PKC-regulated switch may explain the sensory gating that allows animals to discriminate which stimuli are innocuous and appropriate to ignore and which stimuli are more important and should continue to elicit responses.

1. Habituation of reflex responses in vertebrates and invertebrates: a simple form of neural plasticity

Habituation is defined as the gradual waning of a response with repeated presentation of a stimulus. Early physiologists, including Charles Sherrington (1906) and C. Ladd Prosser and Walter Hunter (1936), analyzed habituation of reflexes in mammalian preparations. In the 1960s, Richard Thompson, together with Alden Spencer and Philip Groves, characterized the process of habituation in a simple spinal reflex of cats, recording from the motor neurons that mediate the reflex (Groves and Thompson, 1970; Thompson and Spencer, 1966). They focused on the synaptic input to the motor neurons in an attempt to identify the cellular changes that develop with repeated stimulation that could account for the behavioral change. One important insight made by Thompson and Spencer (1966) and Groves and Thompson (1970) was that two independent processes contribute to the changes in the reflex response that occur with repeated stimulation. In addition to habituation, the repeated stimulus may lead to a strengthening of the response, known as sensitization. Their observations led them to propose the “dual-process theory” in which the behavioral change actually reflects the contribution of these two independent processes. The complicating effect of sensitization impacts many habituation studies, including those discussed below.

In this same era, Jan Bruner, a former student of Jerzy Konorksi, together with Ladislav Tauc, initiated studies of habituation in a much simpler nervous system, the central nervous system (CNS) of the marine snail Aplysia (Bruner and Tauc, 1966). They analyzed habituation of the tentacle withdrawal response in this snail, and identified synaptic depression as a possible mechanism for this simple form of learning. Bruner and Tauc had did not know the identities of either the sensory neurons that mediate the input to the reflex circuit or the interneurons or motor neurons responsible for the withdrawal movement. Instead, their recordings of synaptic input were made from the highly accessible giant neuron R2, which has no functional role in the reflex. Compound EPSPs produced by stimulating an interganglionic connective, which contains axons of interneurons, were used as an indirect indicator of the sensory input to the reflex. Within a few years, Eric Kandel and his colleagues identified a number of motor neurons in the abdominal ganglion that were responsible for a different defensive withdrawal reflex: the siphon-elicited withdrawal of the gill and the siphon (Kupfermann, Castellucci, Pinsker, and Kandel, 1970). This group also identified a population of sensory neurons in the abdominal ganglion that were activated by mechanical stimulation of the siphon skin, thereby defining the circuit for the monosynaptic component of the reflex (Castellucci, Pinsker, Kupfermann, and Kandel, 1970). This was an important advance because it was now possible to study directly, at these synaptic connections between the sensory neurons and motor neurons, the changes that develop during habituation produced by repeated stimuli to the skin. During habituation of the defensive withdrawal reflexes, these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses undergo rapid and profound homosynaptic depression (i.e. depression initiated solely by activation of the synapse itself), as first described by Castellucci and Kandel (1974). Synaptic depression occurs over a wide range of interstimulus intervals (ISIs) from seconds to >100 sec (Byrne, 1982; Eliot, Kandel, and Hawkins, 1994). The contribution of depression at these synapses to short-term habituation of the defensive withdrawal reflex has been confirmed in experiments by Robert Hawkins and his colleagues (Antonov, Kandel, and Hawkins, 1999; Cohen, Kaplan, Kandel, and Hawkins, 1997; Frost, Kaplan, Cohen, Henzi, Kandel, and Hawkins, 1997). Their studies were conducted on reduced preparations consisting of either the gill, siphon and mantle, or the siphon alone, together with the abdominal ganglion, which contains the somata of the centrally located siphon sensory neurons and gill and siphon motor neurons. These simplified preparations enabled the researchers to record the monosynaptic connections from sensory neurons to motor neurons while the actual behavior was elicited.

This review is devoted to discussing our current understanding of the mechanism of short-term synaptic depression at this sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse that would contribute to behavioral habituation over a time course of minutes or tens of minutes. (Although we use the term “short-term,” as this has been the convention in this system, this form of synaptic depression that lasts minutes or tens of minutes could reasonably be considered to be intermediate-term plasticity.) Short-term depression in this system is entirely distinct from long-term depression, both in their underlying mechanisms and in their likely functions. Based on its very rapid reduction and its reversibility, we suggest that “short-term” depression at these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses provides a mechanism of sensory gating. In contrast, long-term depression at these synapses has the characteristics of a mechanism of learning. Whereas short-term depression at these synapses appears to be mediated entirely by presynaptic changes (Castellucci and Kandel, 1974; Manseau, Fan, Hueftlein, Sossin, and Castellucci, 2001), long-term depression that is initiated by extensive stimulation or blocks of stimuli delivered over hours appears to depend upon signals initiated by postsynaptic glutamate receptors, including Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors (Lin and Glanzman, 1996; Mata, Chen, Cai, and Glanzman, 2008), (see also Ezzeddine and Glanzman, 2003). Interestingly, in another invertebrate, C. elegans, long-term habituation one day after training also appears to depend on postsynaptic mechanisms involving glutamate receptors (Rose, Kaun, Chen, and Rankin, 2003). In this review, we first consider mechanisms of short-term depression that have been characterized at synapses in preparations other than in Aplysia.

2. Mechanisms of synaptic depression in other systems

2.1. Depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles as a mechanism of depression

Historically, the earliest proposed mechanism for synaptic depression was depletion of the neurotransmitter that is available for release. Vesicles at synaptic release sites that are available for immediate release are considered to constitute a readily releasable pool (Betz, 1970; Gingrich and Byrne, 1985; Stevens and Tsujimoto, 1995); these vesicles may already be docked at exocytosis sites. In contrast, the larger reserve pool of vesicles must be mobilized over seconds or tens of seconds to replenish the readily releasable pool (Stevens and Wesseling, 1998). In general, most studies that have implicated vesicle depletion as a mechanism of synaptic depression have reached this conclusion because the amount of depression was positively correlated with the amount of transmitter released. This dependence of depression on release suggests a vesicle depletion mechanism. Early studies at the neuromuscular junction observed that when Ca2+ influx was altered, depression increased with increasing release probability (Betz, 1970; Thies, 1965). At some central synapses, including retinal bipolar cell synapses, depression has also been found to be correlated with release probability (von Gersdorff and Matthews, 1997). In contrast, in other cases, vesicle depletion is assumed by default to be the mechanism for depression when other mechanisms that are considered likely have been excluded. For example, at the calyx of Held synapse, Von Gersdorff, Schneggenburger, Weis and Neher (1997) found that presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors make only a small contribution to depression, and presynaptic Ca2+ current is unlikely to inactivate under their stimulus conditions. These negative results led these authors to propose that the primary mechanism that contributes to synaptic depression is depletion of the releasable pool of vesicles.

Changes in spontaneous release of vesicles have also been used as an indicator of changes in the size of the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles. At the neuromuscular junction, Hubbard (1963) observed that synaptic depression was correlated with a decrease in spontaneous release, suggesting a mechanism that involves vesicle depletion. However, it should be noted that some modulatory changes that affect vesicle docking and priming, other than depletion, might reduce both spontaneous release and evoked release.

More direct evidence for the contribution of vesicle depletion to synaptic depression comes from studies that measure the readily releasable pool using hypertonic saline, which initiates dumping of the entire population of releasable vesicles. For example, Rosenmund and Stevens (1996) studied synapses formed by hippocampal pyramidal cells in culture, which undergo depression during 20 Hz stimulation. When stimulation was continued several seconds there was a dramatic reduction in the size of the readily releasable pool of vesicles.

Evidence for the role of vesicle depletion in synaptic depression should also be available from electron microscopy studies of synaptic terminals after stimulation. However, typically in these studies, the synapses are fixed after very extensive stimulation, substantially more than is required to induce short-term depression. For example, Pysh and Wiley (1974) analyzed electron micrographs of synapses in the superior cervical ganglion after 30 minutes of 10 Hz stimulation and found there was a two-fold reduction in the density of synaptic vesicles. In contrast, an electron microscopic study by Applegate and Landfield (1988) examined synapses in hippocampus after one minute of 40 Hz stimulation; although substantial synaptic depression developed with this stimulus protocol, there was no measurable reduction in vesicle density near the active zone membrane. Thus, the reduction in numbers of vesicles determined by electron microscopy may substantially underestimate the vesicle depletion that is found in the experiments that measure the total readily releasable pool with hypertonic saline (Rosenmund and Stevens, 1996). It is possible that micrographs do not provide accurate estimates of the numbers of vesicles docked at the active zone (i.e. the readily releasable pool).

Many of the studies that implicated vesicle depletion in synaptic depression did not actually exclude other candidate mechanisms. Perhaps the reference that is most often cited as evidence for the role of depletion in synaptic depression is a study at the neuromuscular junction by Betz (1970). Although he hypothesized that vesicle depletion might be a contributing factor, interestingly, he suggested that a change in release probability, independent of the number of releasable vesicles, also contributes to depression.

2.2 Use-dependent inactivation of presynaptic Ca2+ channels

Ca2+ channels can undergo transient inactivation initiated either by membrane depolarization or by increased intracellular Ca2+ due to Ca2+ influx (Cens, Rousset, Leyris, Fesquet, and Charnet, 2006). At the Calyx of Held, Forsythe, Tsujimoto, Barnes-Davies, Cuttle, and Takahashi (1998) found that Ca2+-dependent inactivation of P type Ca2+ channels largely accounted for synaptic depression.

2.3 Desensitization of postsynaptic receptors

Many excitatory receptors undergo desensitization with repeated activation. AMPA-type glutamate receptors desensitize rapidly. Using either photorelease of caged glutamate or miniature EPSCs to measure glutamate sensitivity, Otis, Zhang, and Trussell (1996) found that transmitter release with a single action potential caused desensitization of AMPA receptors; the desensitization recovered within 100 milliseconds. Such short-lived desensitization is unlikely to contribute to synaptic depression during behavioral habituation because habituation is typically elicited with ISIs of seconds or tens of seconds.

2.4 Autoreceptors and retrograde signaling

At a wide variety of synapses, the presynaptic terminals contain autoreceptors for the same transmitter(s) released by these terminals. Adenosine autoreceptors have been implicated in synaptic depression initiated by released transmitter. In general, synaptic vesicles contain ATP together with conventional neurotransmitter. ATP is co-released with acetylcholine at the frog neuromuscular synapse. The ATP metabolite adenosine binds to presynaptic purinergic receptors and inhibits transmitter release (Redman and Silinsky, 1994). In other cases, retrograde signals released from the postsynaptic neuron activate presynaptic receptors that downregulate transmitter release. At parallel fiber-to-Purkinje cell synapses in cerebellum, high frequency presynaptic activity causes suppression of transmitter release, which is mediated by release of endocannabinoids from the postsynaptic Purkinje cell; the endocannabinoids act on receptors on presynaptic terminals, resulting in reduced Ca2+ influx (Brown, Brenowitz, and Regehr, 2003).

3. Proposed mechanisms for synaptic depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse in Aplysia

3.1 Short-term homosynaptic depression at sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses involves a presynaptic mechanism, rather than alteration in postsynaptic responses

Numerous mechanisms have been proposed to explain homosynaptic depression at sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses in Aplysia californica. Using quantal analysis in the intact abdominal ganglion of Aplysia, Castellucci and Kandel (1974) determined that after depression, the number of quanta released per presynaptic action potential was reduced. However, the quantal size remained constant. This suggested that short-term synaptic depression was the result of presynaptic mechanisms. Additional studies over the past three decades have confirmed that depression at this synapse with stimulus frequencies ≤1 Hz is mediated by presynaptic changes. Depolarizing potentials elicited by puffer application of glutamate onto motor neurons with ISIs of 1 second or longer do not depress; transient desensitization of the glutamate response was observed only with shorter ISIs (≤ 200 milliseconds) (Antzoulatos, Cleary, Eskin, Baxter, and Byrne, 2003). These ISIs where desensitization occurred are substantially shorter than the intervals used to study behavioral habituation. Puffs of exogenous glutamate applied to sensory neurons and motor neurons in coculture at intervals of 1 minute do not cause depression of these synaptic connections (Armitage and Siegelbaum, 1998). This study where glutamate was delivered to neurons in culture would also argue that synaptic depression is not the result of activation of glutamate receptors on the presynaptic terminals of the sensory neurons. Depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron is also not required, as the development of synaptic depression during a series of single sensory neuron action potentials was not blocked by reversibly blocking glutamate receptors with a specific antagonist (Armitage and Siegelbaum, 1998).

3.2 Ca2+ current inactivation

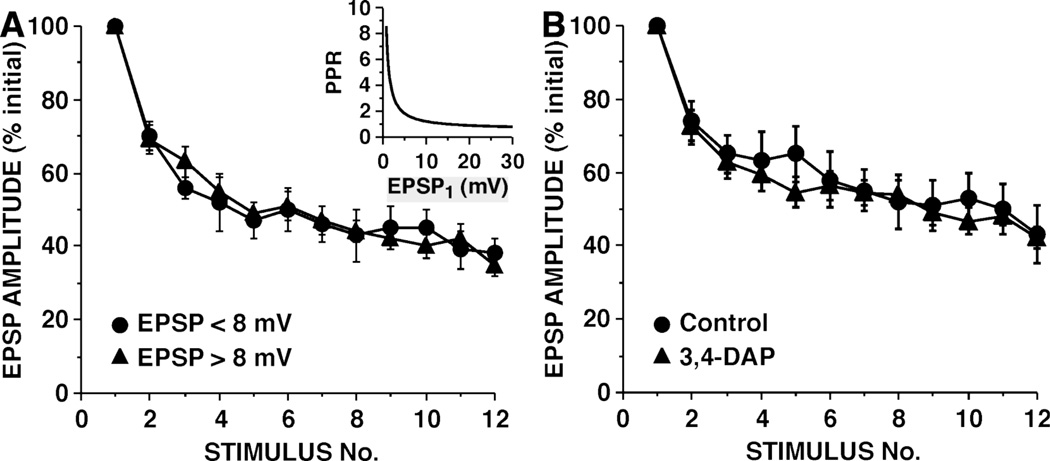

One presynaptic mechanism that could account for depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse is inactivation of Ca2+ current, which would reduce release probability. Klein, Shapiro and Kandel (1980) suggested that Ca2+ current in sensory neurons inactivates with repeated activation. To detect changes in the magnitude of the presynaptic Ca2+ current, these investigators used the potassium channel blocker TEA to prolong the action potential and create a plateau phase, which is largely mediated by Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane. With repeated stimulation of the sensory neuron, the action potential duration decreased, suggesting that Ca2+ influx decreased with each successive action potential. Klein et al. (1980) also measured the Ca2+ current in the soma of the presynaptic sensory neuron under voltage clamp. With repeated depolarizing voltage steps, they observed that the Ca2+ current decreased in parallel with the decline in the amplitude of the EPSP recorded in the motor neuron. These experiments provided evidence that the Ca2+ current inactivates during repeated TEA-broadened action potentials or during repeated 50 millisecond depolarizing voltage steps. However, in these protocols, Ca2+ current inactivation would have been greater than with action potentials in normal saline because the duration of depolarization would have increased more than an order of magnitude. Thus, the contribution of Ca2+ current inactivation would have been overestimated. Contrary to what one might initially conclude, these experiments with TEA-broadened action potentials actually demonstrate that synaptic depression at these synapses is largely independent of Ca2+ current inactivation. Because inactivation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels is use-dependent (Cens et al., 2006), we would expect that if inactivation were the mechanism, then the rate of synaptic depression in these experiments with TEA would be substantially greater than with normal action potentials. In contrast, Klein et al. (1980) observed that the kinetics of synaptic depression were similar in TEA and normal saline. Gover, Jiang and Abrams (2002) made similar observations using a second potassium channel blocker, 3,4-DAP (see Fig. 1B). Based on simulation studies, Gingrich and Byrne (1985) also reached the conclusion that Ca2+ current inactivation alone during the normal duration action potential does not account for depression at this synapse. Sensory neurons in Aplysia contain both dihydropyridine-sensitive and dihydropyridine-insensitive Ca2+ channels; only the latter contribute to transmitter release (Edmonds, Klein, Dale, and Kandel, 1990; Eliot, Kandel, Siegelbaum, and Blumenfeld, 1993). Armitage and Siegelbaum (1998) used fluorescent Ca2+ indicators to directly measure Ca2+ influx at presynaptic varicosities of sensory neurons through the dihydropyridine-insensitive Ca2+ channels. No change in Ca2+ influx through these channels that initiate release was observed during synaptic depression.

Figure 1.

Strong and weak sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synaptic connections undergo synaptic depression with an identical time course, but differ in their paired-pulse ratios. Inset: The inverse relationship between paired-pulse ratio (PPR) and initial EPSP amplitude. Curve is hyperbolic function from Jiang and Abrams (1998), which was fit to empirical paired-pulse ratios for non-depressed sensory neuron synapses. The paired-pulse ratio was measured with a 50 millisecond interval between the two pulses. (PPR = amplitude of EPSP2/ampltude of EPSP1.) Note, that, in contrast to initially weak synapses, initially strong synapses show relatively little paired-pulse facilitation, suggesting that these stronger synapses have higher release site probabilities.

A. Synaptic depression for strong and weak synapses. Synaptic connections are grouped according to initial EPSP amplitudes as either strong (> 8 mV) or weak (< 8 mV) (mean EPSP on trial #1: 22.3 ± 2.1 for strong synapses and 5.7 ± 0.3 mV for weak synapses). In each experiment, EPSP amplitude is normalized to the amplitude of the EPSP on trial #1. Mean amplitude of all the EPSPs on trial #12 was 36 ± 3% of the initial amplitude. (A 15 second ISI was used in all experiments measuring synaptic depression in this and subsequent figures.)

B. Increasing release by broadening the sensory neuron action potential with the K+ channel blocker 3,4-DAP does not affect the rate of synaptic depression. Superfusing abdominal ganglia with 5 µM 3,4-DAP prior to and during experiments resulted in an approximately 3-fold increase in the duration of the sensory neuron action potential, and approximately a 50% increase in the amplitude of the EPSPs. (Reprinted from Gover et al., 2002.)

3.3 Depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles as the primary mechanism for synaptic depression during habituation

Several studies have suggested that depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles is the mechanism behind synaptic depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses in Aplysia. Gingrich and Byrne (1985) developed a mathematical model of depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse that included Ca2+ channel inactivation, a limited readily releasable pool of vesicles, and a reserve pool of vesicles from which vesicles are translocated to refill the releasable pool. As mentioned above, they concluded from this model that Ca2+ channel inactivation is not sufficient to account for depression. Instead, they proposed that the major mechanism underlying synaptic depression is depletion of the readily releasable pool of transmitter. Thus, much like Von Gersdorf et al. (1997) who studied synaptic depression at the giant synapse of the Calyx of Held in mammals, the lack of involvement of another candidate mechanism was taken as evidence for the importance of depletion of synaptic vesicles. The empirical data at Aplysia sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses revealed a dependence of the extent/rate of recovery from depression on the ISI during the series of stimuli that initiated depression; shorter ISIs resulted in more rapid or more effective recovery (Byrne, 1982). To match the recovery data with their model, Gingrich and Byrne (1985) found that in addition to depletion, they needed to include activity-dependent, Ca2+-mediated, mobilization of transmitter from the reserve pool to the readily releasable pool. [Similar activity-dependent refilling of the readily releasable pool of vesicles was described at hippocampal synapses more than a decade later (Stevens and Wesseling, 1998).] Gingrich and Byrne (1985) were careful to indicate that mobilization might reflect transmitter synthesis rather than vesicle translocation. Most subsequent analyses have focused on vesicle translocation into the readily releasable pool (e.g. Khoutorsky and Spira, 2005). As discussed below, at least one component of this activity-dependent increase in synaptic strength after depression may actually represent superimposed facilitation, rather than actual recovery.

An electron microscopic study of the sensory neuron to-motor neuron synapse provided direct evidence that vesicle depletion contributes to synaptic depression (Bailey and Chen, 1988). However, the stimulation protocol, which of necessity sampled only a single time point, consisted of a series of either 35 to 250 stimuli. Thus, the protocol with which there was an observed reduction in the number of vesicles adjacent to the active zone membrane involved much more extensive stimulation than is required to produce depression at these synapses. Substantial depression is observed after a single stimulus and near-asymptotic depression typically develops after only 5 stimuli (Byrne, 1982; Castellucci and Kandel, 1974; Gover et al., 2002). Thus, depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles can contribute to depression, but probably only with relatively prolonged presynaptic activity. Recent evidence implicated the Ca2+-activated protease calpain both in modulation of depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse and in serotonin-induced facilitation after depression (Khoutorsky and Spira, 2005). This intriguing observation has been interpreted to indicate that this protease acts to untether vesicles in the reserve pool, and thereby initiates mobilization of vesicles to the readily releasable pool. Although this is a plausible model, another possible function for calpain is the proteolytic cleavage of protein kinase C (PKC), converting the enzyme to the persistently active PKM form (Sutton, Bagnall, Sharma, Shobe, and Carew, 2004). PKC is known to participate in facilitation of depressed sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses by serotonin (Ghirardi, Braha, Hochner, Montarolo, Kandel, and Dale, 1992; Manseau et al., 2001), and also acts to prevent the development of depression during bursts of activity (see below). Thus, calpain cleavage of PKC could reduce synaptic depression.

3.4 Switching of release sites to a silent state as a mechanism of synaptic depression

Several characteristics of homosynaptic depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse are not consistent with a depletion model. Rather remarkably, depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse does not depend on the probability of release. Jiang and Abrams (1998) observed that initial synaptic strength (i.e., EPSP amplitude) was correlated with release probability, as measured by the paired-pulse ratio. Paired-pulse ratios at Aplysia sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses are inversely related to the probability of release, as is found in many, though not all, studies in other systems (Augustin, Korte, Rickmann, Kretzschmar, Sudhof, Herms, and Brose, 2001; Debanne, Guerineau, Gahwiler, and Thompson, 1996; Mallart and Martin, 1968; Schoch, Castillo, Jo, Mukherjee, Geppert, Wang, Schmitz, Malenka, and Sudhof, 2002). The inverse relationship between paired-pulse facilitation and release probability at these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synaptic connections was confirmed by Gover et al. (2002), who observed a decrease in paired-pulse facilitation when they increased release at weak synapses by increasing Ca2+ influx. Although strong and weak synapses differed by more than three-fold in paired-pulse facilitation, these synapses underwent synaptic depression with identical kinetics (Fig. 1A) (Gover et al., 2002; Jiang and Abrams, 1998). Thus, synaptic connections with a high probability of release depress at the same rate as synapses with low probabilities of release (Jiang and Abrams, 1998). This is true even when the probability of release is artificially increased by increasing Ca2+ influx by prolonging the action potential with potassium channel blockers (Fig. 1B) (Gover et al., 2002; see also Klein et al., 1980). Reciprocally, depression was not altered when release was reduced under low Ca2+ / high Mg2+ conditions (Castellucci and Kandel, 1974). This is inconsistent with a model where a reduction in the readily releasable pool of vesicles is responsible for depression. Similar experimental evidence that depression is independent of release was obtained more recently by Negroiu and Abrams (unpublished results), who reduced the extracellular Ca2+ concentration by 60%, decreasing release by nearly five-fold; despite the dramatic reduction in release, depression developed with the same kinetics as in normal Ca2+ and reached the same final level. Finally, depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse is independent of stimulation frequency over a large range; after a single stimulus, equivalent depression was observed with ISIs of 3, 10 or 30 seconds (Byrne, 1982). Again, this is inconsistent with a depletion model where a readily releasable pool of vesicles is being reduced and replenished from an auxiliary pool of vesicles at a constant rate. Shorter ISIs may enhance recovery from synaptic depression due to higher Ca2+ levels, as suggested by Byrne (1982) and Gingrich and Byrne (1985); however, at the time of the second action potential in a series, there should be no difference in the Ca2+ rise produced by the preceding first action potential.

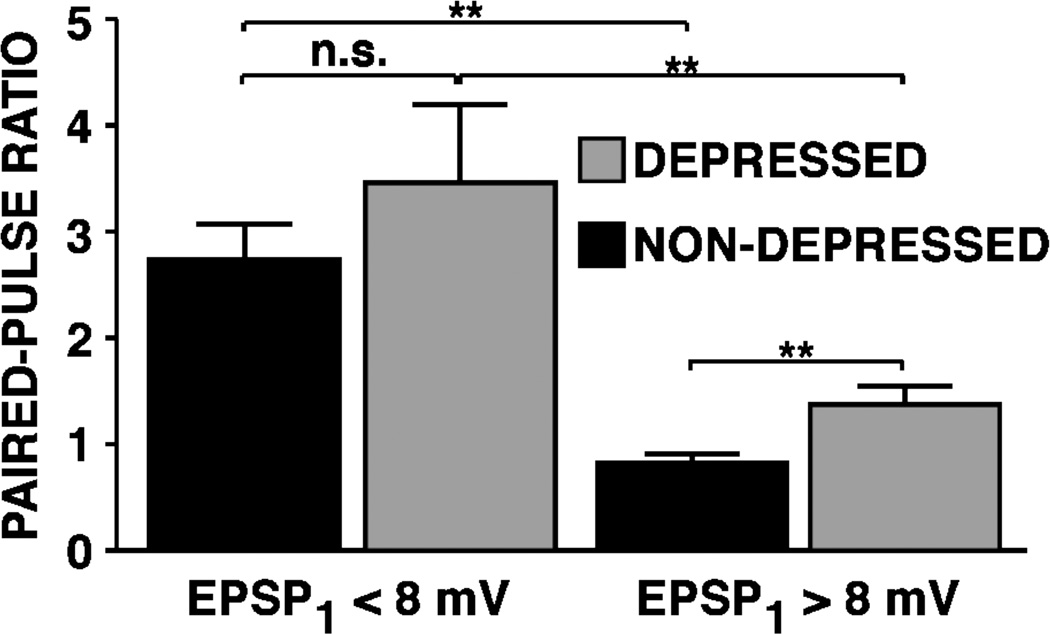

Jiang and Abrams (1998) also observed that synaptic depression did not convert synapses with high probability of transmitter release into synapses with low probability of release, as measured by the paired-pulse ratio (Fig. 2). Such a decrease in release probability should occur with vesicle depletion. It is noteworthy that two decades earlier, Farel and Thompson (1976) made a very similar observation in studying synaptic depression at synapses onto spinal motor neurons. Because depletion of vesicles must result in a decrease in release probability per release site, this observation would argue against depletion as a major mechanism of synaptic depression during habituation at these synapses in Aplysia.

Figure 2.

Synaptic depression is not accompanied by a substantial reduction in release probability, as indicated by the paired-pulse ratio. Paired-pulse ratios of large and small synapses tested once, either without depression (NON-DEPRESSED) or 15 seconds after a series of 15 single action potentials (DEPRESSED). The average initial EPSP amplitudes were 14.8 mV and 4.4 mV for the large and small synapses, respectively, in the nondepressed group; for synapses in the depressed group, the average EPSP amplitudes before depression were 16.7 mV and 5.7 mV for the large and small synapses, respectively. Both before and after depression, the large synapses (>8 mV) differed significantly from the small synapses (<8 mV) in their paired-pulse ratios. After synaptic depression the paired-pulse ratio for large synapses increased significantly; nevertheless, although the depressed EPSP amplitudes were approximately the same as the small synapses prior to depression, the paired-pulse ratios remained much smaller. In the case of the small synapses, despite comparable synaptic depression, there was not a significant change in the paired-pulse ratios. Thus, overall there was not a sufficient decrease in release probability to account for the synaptic depression. (Modified from Jiang and Abrams, 1998.)

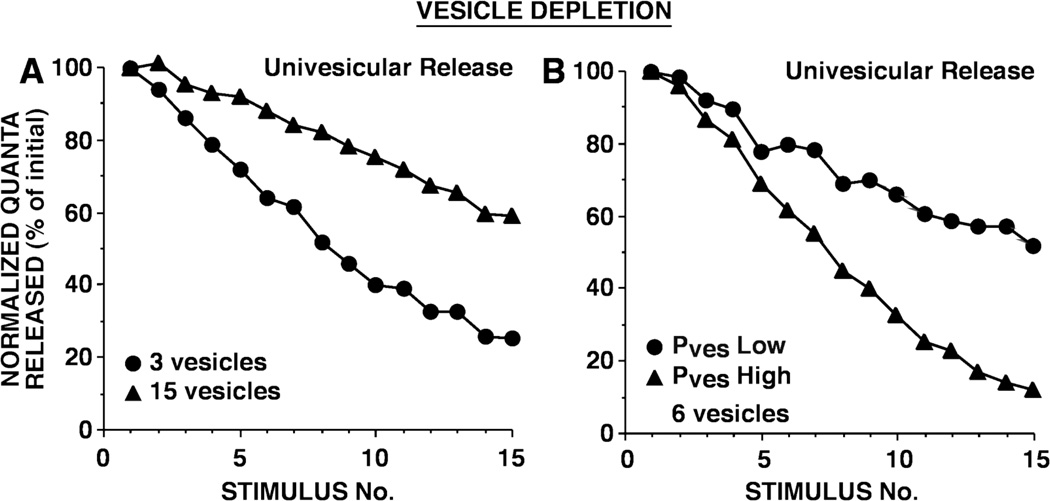

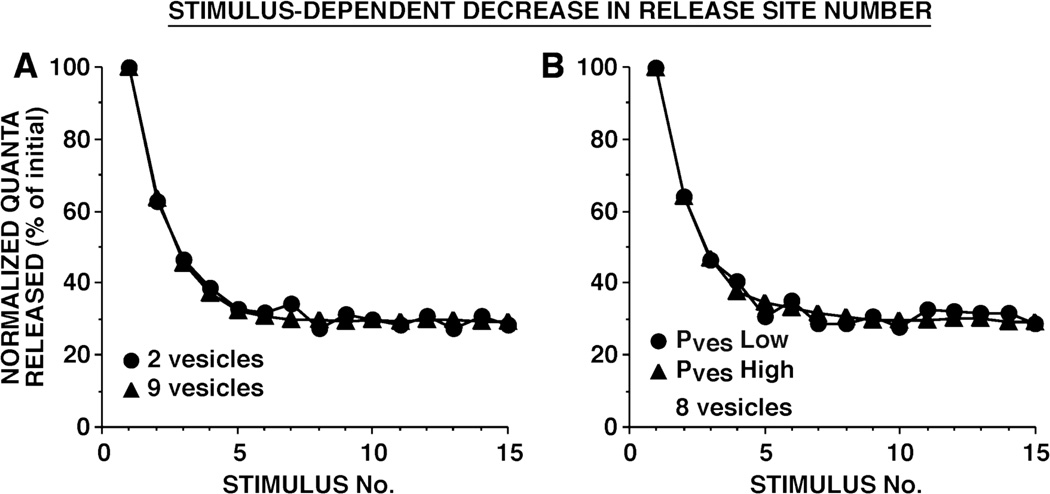

Two independent computational analyses have suggested that depression at these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses is the result of silencing of individual release sites (Gover, Jiang, and Abrams, 1999; Gover et al., 2002; Royer, Coulson, and Klein, 2000). Gover et al. (1999, 2002) focused on the finding of Jiang and Abrams (1998) that the rate of depression at the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse is independent of initial synaptic strength (where strong and weak synapses differ in their probability of release, as discussed above, rather than simply in the number of release sites). They developed mathematical models of homosynaptic depression at this synapse to explore which classes of mechanisms could produce depression that was independent of initial synaptic strength (Fig. 1). These simulations included multiple release sites, each with a release probability <1.0; in contrast, most computer simulation studies of synaptic plasticity model a single giant synapse at which multiple vesicles are released with each stimulus. The outcomes possible with these two classes of models are substantially different; in particular, the gradual switching off of individual release sites would not be possible with a single giant synapse model. In their effort to determine what mechanism of homosynaptic depression would allow strong and weak synapse to depress at similar rates, Gover et al. (2002) considered five mechanisms of synaptic depression:

vesicle depletion, which by default must be dependent on vesicular release (Fig. 3);

reduction in the probability of release of individual releasable vesicles after a release event;

reduction in the probability of release of individual releasable vesicles after an action potential, but independent of a release event;

silencing of release sites after a release event, and

silencing of release sites, after an action potential, but independent of a release event (Fig. 4).

Of these alternatives, the only mechanism that allowed for both strong and weak synapses to depress at the same rate was silencing of release sites, independent of a release event (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Simulated synaptic depression as a result of vesicle depletion. The simulated synapses were representations of a synaptic connection between a single siphon sensory neuron and a single motor neuron, consisting of 40 release sites (active zones); each release site was functionally independent. In these Monte Carlo simulations, vesicle release at each site occurred in a stochastic manner. In A, strong and weak synapses differed in their initial number of readily releasable vesicles. In B, strong and weak synapses differed in the release probability of individual vesicles (Pves). During each simulation, the per vesicle release probability and the number of active release sites remained constant. In both A, B, there was univesicular release, in which at a release site, after an initial vesicle release event, further release was inhibited for 5 msec. Similar results were obtained with limited multivesicular release, in which after an initial release event, the release probability of the release site was reduced by a factor of 0.66 and then recovered exponentially with a time constant of 3 msec. The per vesicle release probability was selected to achieve in A, a per site release probability of 0.9 had there been 20 releasable vesicles, and in B, a per site release probability of 0.25 and 0.75 for Pves Low and Pves High, respectively, with 6 releasable vesicles. Average initial numbers of quanta released were: for A, 11.4 for 3 vesicles and 32.6 for 15 vesicles; and for B, 11.0 for Pves Low and 29.7 for Pves High. Note that in A, strong synapses underwent depression at a slower rate than weak synapses, whereas in B, strong synapses underwent depression at a faster rate than weak synapses. In other simulation experiments, Pves values were two- and four-fold smaller; with these lower Pves values, strong and weak synapses still depressed at different rates, although with the smallest Pves values tested, synaptic depression was extremely modest because minimal depletion occurred. (Reprinted from Gover et al., 2002.)

Figure 4.

Simulated depression as a result of stimulus-dependent decrement in the number of active release sites. In these models, Nsite decremented exponentially with each presynaptic action potential. During each simulation, the number of releasable vesicles and the per vesicle release probability remained constant. In A, strong and weak synapses differed in the number of releasable vesicles. In B, strong and weak synapses differed in the per vesicle release probability. (Reprinted from Gover et al., 2002.)

Additional evidence for silencing of sensory neuron release sites was obtained independently by Royer et al. (2000), using modified binomial quantal analysis to examine synaptic depression at synapses formed between isolated somata of sensory neurons and motor neurons placed together in culture. They demonstrated that the binomial parameter p (release probability) does not change after depression or facilitation with serotonin; in contrast, the binomial parameter n (number of release sites) does decrease with depression. Royer et al. (2000) also modeled the kinetics of synaptic depression and recovery. Their model of the kinetics of synaptic depression demonstrated that p remains constant, in agreement with their quantal analysis. These data suggest that the probability of release does not change gradually, but, that individual release sites are simply silenced, or switched off, during development of depression. Furthermore, Royer et al. (2000) argued that given their data, if p were nonuniform across release sites, then homosynaptic depression due to silencing of release sites would be independent of release [which is consistent with the conclusions of Gover et al. (2002)].

3.5 Other evidence suggesting depletion of vesicles is not the major mechanism for synaptic depression at Aplysia sensory neuron synapses

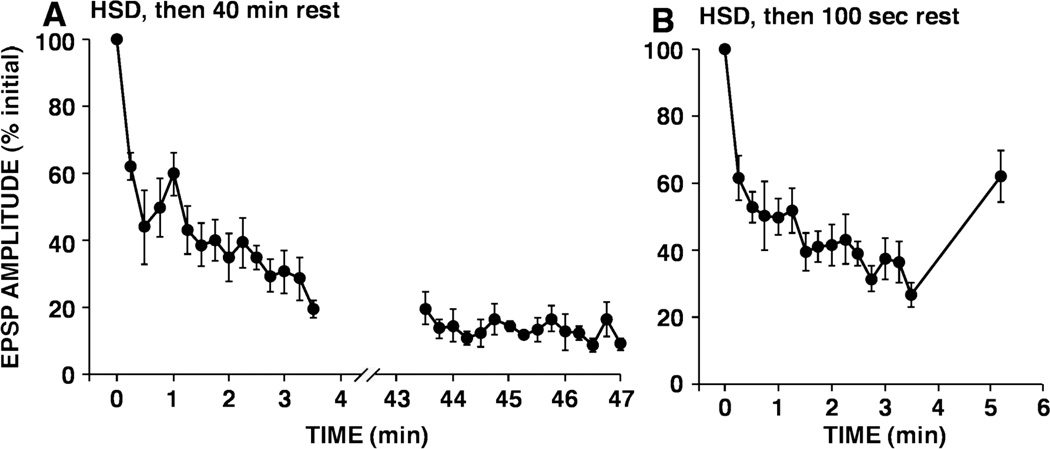

In addition to these two quantitative analyses of depression at sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses in Aplysia, a substantial number of observations at these synapses suggest that depression is not a depletion or exhaustion phenomenon. Gover et al. (2002) found that once induced, synaptic depression often persists for tens of minutes, with virtually no recovery. Although in some series of experiments recovery is observed, this process occurs over many minutes, which is more than an order of magnitude slower than recovery from short-term depression at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction (Betz, 1970; Thies, 1965) or than replenishment of the readily releasable pool at hippocampal synapses (Rosenmund and Stevens, 1996). In Aplysia, a lack of recovery after what has been traditionally termed “short-term synaptic depression” was originally observed by Carew and Kandel (1973) in one of the earliest studies of depression of afferent synaptic input. These authors stimulated peripheral nerves to the siphon or gill and recorded compound synaptic potentials in motor neurons. The synaptic depression that developed during a series of 10 stimuli at a 30 second ISI only partially recovered after 90 minutes of rest (Carew and Kandel, 1973). The most thorough parametric study of depression at these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses was done by Byrne (1982). In his experiments, there was a substantial increase in synaptic transmission 100 seconds after the end of stimulation, which could be interpreted as partial replenishment of the readily releasable pool. Gover et al. (2002) confirmed this observation (Fig. 5B), but found that at much later time points (e.g. 40 minutes after the end of stimulation), no recovery was detectable (Fig. 5A). This suggests that after a period of low frequency stimulation, in addition to the depression that develops, sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses undergo transient facilitation. Byrne (1982) also observed that at higher frequencies of stimulation (e.g., with an ISI of one or three seconds), the apparent recovery from depression was more rapid. Negroiu and Abrams (unpublished results) noticed that the stability of depression was actually greater after 5 stimuli than after 15 stimuli, which is consistent with the proposal that greater activity promotes recovery from depression.

Figure 5.

Limited recovery of depressed sensory neuron synaptic connections with rest.

A. Persistent depression of sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synaptic connections 40 minutes after induction of synaptic depression. Sensory neurons were initially activated 15 times. After induction of synaptic depression (i.e. after the 15th stimulus, synapses were rested 40 minutes and again stimulated repetitively. Note, there was no apparent recovery of depressed sensory neuron connections. Note also that no additional depression was induced by the subsequent stimulation after rest.

B. After depression develops at sensory neuron synapses, EPSPs show partial recovery after a 100 seconds period of rest. After the 15th stimulus, synapses were rested 100 seconds and then sensory neurons were stimulated once more. In both A and B, during the series of 15 stimuli, the ISI was 15 sec. (Reprinted from Gover et al., 2002.)

4. Evidence from other systems suggesting that vesicle depletion is not the primary mechanism responsible for synaptic depression

One of the earliest findings suggesting that vesicle depletion may not be a major contributor to synaptic depression was made by Zucker and Bruner (1977) at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. They observed dramatic depression after only a single stimulus. Moreover, when release was reduced nearly four-fold using high Mg2+ saline, the rate of depression was unchanged. This might be considered an anomaly of this particular invertebrate synapse. However, the evidence in mammalian CNS that vesicle depletion explains synaptic depression with modest stimulation protocols is surprisingly weak.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for vesicle depletion comes from studies that assess the size of the readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles by using hypertonic sucrose saline to initiate massive vesicle dumping. Rosenmund and Stevens (1996) elegantly demonstrated in hippocampal neurons in culture that activity and hypertonic saline deplete the same pool of vesicles. However, these same results raise doubts as to whether depletion is the primary mechanism contributing to the depression that is observed with modest stimulation. Although 20 Hz stimulation depleted the readily releasable pool after 5 seconds, the synaptic depression during this high frequency firing was much more rapid than would be explained by vesicle depletion, given release probabilities that are less than 0.5 (Rosenmund, Clements, and Westbrook, 1993) and a readily releasable pool of one to two dozen vesicles (Stevens and Tsujimoto, 1995). After only 3 stimuli the synapses depressed approximately 50% (Fig. 6C in Rosenmund and Stevens, 1996). If depression were mediated by vesicle depletion, to achieve such dramatic depression after a few stimuli, release probabilities of individual sites would need to be upwards of 95% [and there would be need to be unrestricted multivesicular release (e.g. Fig. 7 in Gover et al., 2002,)]. The measurements by Rosenmund and Stevens (1996) of synaptic currents suggest that single isolated action potentials release only 4% of the readily releasable pool. Summing release during 20 Hz stimulation (and taking into account the decrease in release during consecutive action potentials), the first three spikes should release approximately 11% of the readily releasable pool of vesicles; yet by the fourth action potential, depression was nearly 50%. We do not mean to suggest that substantial vesicle depletion does not result in synaptic depression. Rather depression with relatively few stimuli or with low frequency stimulation can not be explained primarily by depletion.

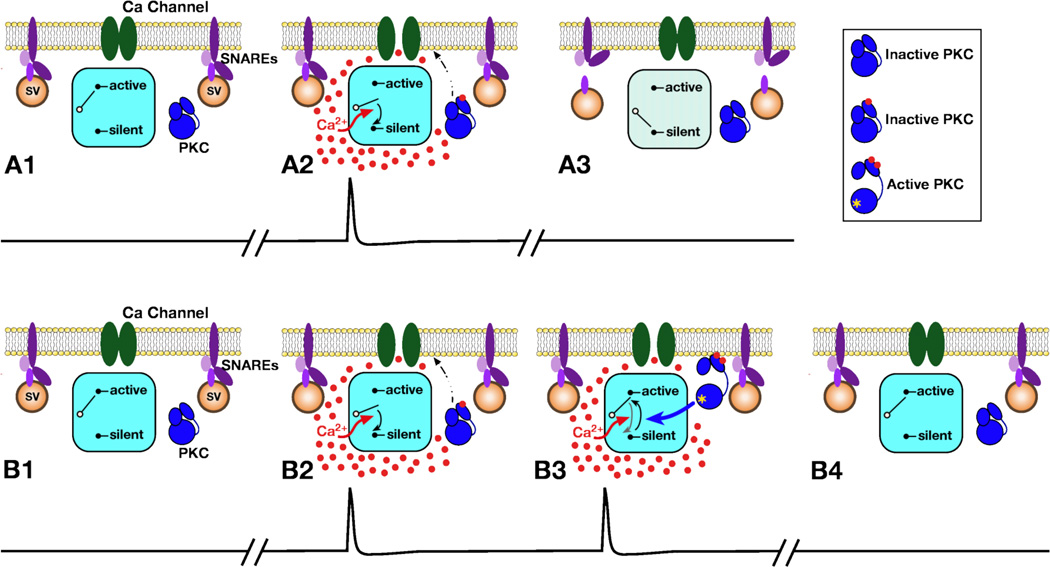

Figure 6.

Ca2+ influx and PKC toggle the sensory neuron release sites between active and silent states, depending on the temporal pattern of Ca2+ influx. PKC serves as a sensitive detector of the presynaptic firing pattern. A: During a single action potential (trace in A2), Ca2+ influx initiates the switching off of release sites. This switching off changes the release state of synaptic vesicles (SV), shown as a dissociation of the previously docked SNARE proteins in A3. (Although the nature of the synaptic switch is not fully understood, the small G protein Arf appears to play a central role.) Note, in A2, Ca2+ binding to the C2 domain of PKC initiates the translocation of the kinase to the membrane, but PKC remains associated with the membrane only briefly (for approximately 200 milliseconds). B: Bursts of action potentials prevent the switching off of sensory neuron release sites. Ca2+ influx during the first action potential in the burst (B2) causes translocation of PKC, [shown with one Ca2+ ion bound to the C2 domain (red dot)]. As in A2, Ca2+ initiates the switching off of the release site. If a second action potential occurs within 200 milliseconds (B3), PKC is still associated with the plasma membrane and binds an additional Ca2+ ion (which is coordinated by the phospholipid and the C2 domain). When the additional Ca2+ ion binds, PKC is activated (shown by conformational change and yellow asterisk) and its association with the membrane is stabilized. Phosphorylation by PKC interrupts the silencing mechanism, via an unknown target protein. The silencing process must require at least a couple of hundred milliseconds to be completed or consolidated; within this time window, PKC activation can completely prevent the depression process. In B4, the synapse remains in the active state. Thus, in parallel, Ca2+ initiates the switching off of release sites, which is evident as synaptic depression, and the translocation and activation of PKC, which prevents synaptic depression.

5. Ca2+ influx initiates the silencing of release sites during depression at sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse in Aplysia

Depression develops with normal kinetics when Ca2+ influx is reduced, as described above. This raises the question of whether Ca2+ influx is responsible for initiating this form of synaptic depression that is independent of vesicle release. We tested whether depression occurred when Ca2+ influx was entirely eliminated by superfusing ganglia with nanomolar Ca2+ saline. Sensory neurons were stimulated to fire a series of five action potentials in low Ca2+ saline, at a 15 second interval as in the normal depression protocol. Before and after this depression protocol, synapses were tested in normal saline. In the absence of Ca2+ influx, no detectable synaptic depression developed. Thus the switching off of sensory neuron release sites during repetitive presynaptic activity appears to be initiated by presynaptic Ca2+ influx.

6. The switch that silences sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses during depression in Aplysia involves the small G protein Arf

We have been attempting to identify the molecular components of this synaptic switch that turns off release at sensory neuron synapses during depression. One possibility is that because facilitation of depressed synapses involves protein kinase C (Ghirardi et al., 1992; Manseau et al., 2001), the switching of synapses to a silent state is mediated by a protein phosphatase. Indeed, some types of long-term depression involve protein phosphatases (Mulkey, Endo, Shenolikar, and Malenka, 1994; Norman, Thiels, Barrionuevo, and Klann, 2000; Tavalin, Colledge, Hell, Langeberg, Huganir, and Scott, 2002) (see also Ezzeddine and Glanzman, 2003). However, several inhibitors of serine/threonine phosphatases had no effect on the development of depression (Negriou and Abrams, unpublished results). Thus, this rapidly-induced form of synaptic depression is not due to dephosphorylation mediated by protein phosphatases.

Several lines of indirect evidence suggested that a small guanine nucleotide-binding protein, (G protein) plays a central role in the development of synaptic depression at these afferent synapses. We screened for involvement of a small G protein either in the Arf or Rho families. Inactivation of Rho family members with bacterial toxins injected presynaptically had no effect on either synaptic strength or on the development of synaptic depression. In contrast, a general inhibitor of Arf signaling powerfully inhibited transmission at sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses and occluded the development of synaptic depression. Similarly, a binding domain of an Arf effector protein acted as a dominant negative and substantially reduced the depression that developed with single action potentials. Reciprocally, we found that constitutively active Arf6, when injected into presynaptic sensory neurons, prevented the development of synaptic depression (McKay et al. 2007; Lu et al. 2008). These results suggest that at presynaptic sites, when Arf is in the active state, with GTP bound to it, sensory neuron synaptic terminals release transmitter. During synaptic depression, Arf is apparently switched to the inactive, GDP-bound state, resulting in silencing of these release sites. Because synaptic depression is initiated by Ca2+, the inactivation of Arf must also be triggered by Ca2+. Arf itself is not Ca2+ regulated; therefore, Ca2+ must interact with an upstream protein that regulates Arf.

Two aspects of the switching off of release sites during burst dependent protection remain to be elucidated. 1) the all or none, or bistable nature of the switch and 2) the relative stability, or persistence, of the depressed and non-depressed states. It is not clear how Arf would contribute to either of these characteristics. Perhaps these features reflect a property of a downstream effector protein regulated by Arf, rather than of Arf itself. It is noteworthy that compared to other small G proteins, Arf has a relatively low level of endogenous GTPase activity; this could contribute to stabilization of the active configuration.

7. Bursts of sensory neuron activity prevent the development of homosynaptic depression

We recently identified a mechanism by which depression is prevented at these synapses by brief bursts of presynaptic action potentials. Whereas individual action potentials in sensory neurons cause synaptic depression, when sensory neurons fire brief bursts of only 2 to 4 spikes at a frequency of 5 Hz or greater, the development of synaptic depression is largely or completely prevented. Typically, after 15 trials with bursts of 4 spikes, the EPSP is still between 80% and 120% of initial amplitude. We call the elimination of synaptic decrement when sensory neurons fire brief bursts of spikes “burst-dependent protection” from synaptic depression. If synapses are first depressed with a series of single action potentials, and the stimulus pattern is changed to bursts of 4 spikes per trial, there is partial recovery of transmission within several trials. Because the bursts are substantially less effective in producing recovery from depression than in protecting naïve synapses, we believe that bursts of spikes actually prevent the initiation of depression. It should be emphasized that because the subsequent spikes in each burst cause additional transmitter release, burst-dependent protection from synaptic depression is incompatible with a depletion model of synaptic depression. Burst-dependent protection does not represent a transient, facilitatory process superimposed on top of synaptic depression [(such as the transient facilitation observed shortly after a series of single action potentials that initiate synaptic depression (see, for example, Figure 5B)]. The protection from depression persists for tens of minutes, much as does depression itself at these sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses. Thus, activation of the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapse with a burst actually appears to prevent the development of synaptic depression, rather than initiating an independent form of plasticity (Jiang et al., submitted).

Burst-dependent protection from synaptic depression involves Ca2+-dependent activation of protein kinase C (PKC). Chelating Ca2+ in the presynaptic sensory neuron with intracellular EGTA, which is not a sufficiently rapid buffer to block transmitter release, eliminates burstdependent protection. In contrast, chelating Ca2+ in the postsynaptic motor neuron with BAPTA did not reduce burst-dependent protection. Similarly, reducing Ca2+ influx, by decreasing the concentration of extracellular Ca2+ prevents burst-dependent protection. Both of these manipulations reduce, but do not eliminate transmitter release. As in the experiments discussed above, although transmitter release is reduced, the rate at which synapses undergo depression is unaffected (see Fig. 1). Injection of a specific peptide inhibitor of PKC into the presynaptic sensory neuron blocks burst-dependent protection, as do cell-permeant kinase inhibitors that inhibit PKC.

Because broadened action potentials that are accompanied by much greater Ca2+ influx do not initiate protection from synaptic depression, we conclude that the temporal pattern of Ca2+ influx during bursts must be critical for activating burst-dependent protection. One possibility is that Ca2+ influx during the first action potential in the burst causes PKC at the active zone to translocate to the membrane, where it interacts with phospholipid, and the subsequent rise in free Ca2+ during the second action potential is responsible for stably activating the PKC. This seems plausible because for some mammalian Ca2+-activated PKC isoforms, an additional Ca2+ binding site is formed by the phospholipid-C2 domain complex (Kohout, Corbalan-Garcia, Torrecillas, Gomez-Fernandez, and Falke, 2002). Thus, stable activation may require the formation of this additional Ca2+ binding site after translocation of PKC to the membrane (Fig. 6B3). Because substantial burst-dependent protection is activated by bursts of as few as two action potentials at 20 Hz, PKC must be rapidly translocated to the membrane. After translocation, PKC would be available for activation by the second Ca2+ transient during the next action potential, until the kinase dissociates from the plasma membrane. Because burst-dependent protection occurs at stimulus frequencies of 5 Hz, but not 2 Hz, we predict that PKC will dissociate within 200 milliseconds. Thus, PKC, which translocates in and out of the membrane with activity, may serve as a highly sensitive detector of the pattern of sensory neuron firing (Fig. 6). When tactile stimuli are sufficiently intense to produce sensory neuron firing at 5 Hz, but not at 2 Hz, PKC would be translocated and activated, preventing depression.

Conclusion

There is a widespread belief that depletion of the readily releasable pool of vesicles is a major mechanism responsible for synaptic depression. With the ISIs that are typically used in studies of habituation, from several seconds to minutes, vesicle depletion is unlikely to contribute substantially to synaptic depression. At the sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synaptic connections in the circuit for the defensive siphon withdrawal reflex of Aplysia, evidence indicates that synaptic depression develops independently of transmitter release and does not involve depletion. Rather, synaptic depression is mediated by an activity-dependent switching off of release sites that is initiated by Ca2+ influx. This silencing of release sites can persist for tens of minutes. In contrast to the silencing of release sites initiated by single spikes, during bursts of spikes, the additional Ca2+ influx blocks the switching off process via a PKC-mediated mechanism. The molecular nature of the switch that is the target of Ca2+ and PKC is under investigation.

Depression of afferent synapses during habituation is adaptive, as it enables animals to ignore irrelevant stimuli and focus on behaviorally important events,. However in Aplysia, once these sensory synapses are depressed, animals could be unresponsive to stimuli that may damage the skin, making them susceptible to injury. Although it may be behaviorally adaptive to ignore repeated innocuous stimuli, it is critical to remain responsive to biologically important stimuli, even if they occur repetitively. The sensory neurons in the abdominal ganglion that innervate the siphon have relatively high thresholds to tactile stimuli, and have been proposed to function as nociceptors (Illich and Walters, 1997). If the rapid and persistent synaptic depression that occurs at sensory neuron-to-motor neuron synapses occurs in feral animals in marine environments, how do these synapses still transmit important mechanosensory information? Why are these invertebrates not chronically unresponsive to all tactile stimuli, even noxious stimuli? For example, biting movements of a small carnivore are likely to have a repetitive component; it would be highly maladaptive if synapses from nociceptors were chronically depressed. The synaptic switch process described here, which silences synapses when they are activated with just suprathreshold stimuli, but maintains synaptic transmission when stimuli are sufficiently intense to activate sensory neurons in bursts, provides a mechanism to maintain responsiveness to important events. With stimuli that are sufficiently intense to activate presynaptic sensory neurons in bursts, synaptic transmission should be maintained. Thus, burst-dependent protection should be able to prevent synaptic depression with important environmental stimuli.

These same synapses undergo Hebbian plasticity during associative learning (Antonov, Antonova, Kandel, and Hawkins, 2003; Murphy and Glanzman, 1996; 1997). Hebbian strengthening of synaptic connections during learning requires effective depolarization of postsynaptic cells by afferent input (Brown, Chapman, Kairiss, and Keenan, 1988; Kelso, Ganong, and Brown, 1986; Kerchner and Nicoll, 2008), which would not be possible if the synaptic input from the stimulus decremented dramatically. If the Hebbian plasticity is initiated by repeated presentation of a sensory stimulus, the afferent input must be able to continue to activate the postsynaptic neuron over time. Therefore burst-dependent protection may play an important role both in maintaining effective responses to threatening stimuli that are repetitive and in associative learning.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antonov I, Antonova I, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Activity-dependent presynaptic facilitation and hebbian LTP are both required and interact during classical conditioning in Aplysia. Neuron. 2003;37:135–147. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonov I, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. The contribution of facilitation of monosynaptic PSPs to dishabituation and sensitization of the Aplysia siphon withdrawal reflex. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10438–10450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10438.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antzoulatos EG, Cleary LJ, Eskin A, Baxter DA, Byrne JH. Desensitization of postsynaptic glutamate receptors contributes to high-frequency homosynaptic depression of aplysia sensorimotor connections. Learn Mem. 2003;10:309–313. doi: 10.1101/lm.61403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applegate MD, Landfield PW. Synaptic vesicle redistribution during hippocampal frequency potentiation and depression in young and aged rats. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1096–1111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01096.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage BA, Siegelbaum SA. Presynaptic induction and expression of homosynaptic depression at Aplysia sensorimotor neuron synapses. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8770–8779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08770.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin I, Korte S, Rickmann M, Kretzschmar HA, Sudhof TC, Herms JW, Brose N. The cerebellum-specific Munc13 isoform Munc13-3 regulates cerebellar synaptic transmission and motor learning in mice. J Neurosci. 2001;21:10–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00010.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CH, Chen M. Morphological basis of short-term habituation in Aplysia. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2452–2459. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02452.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz WJ. Depression of transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction of the frog. J Physiol (Lond) 1970;206:629–644. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SP, Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG. Brief presynaptic bursts evoke synapse-specific retrograde inhibition mediated by endogenous cannabinoids. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1048–1057. doi: 10.1038/nn1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TH, Chapman PF, Kairiss EW, Keenan CL. Long-term synaptic potentiation. Science. 1988;242:724–728. doi: 10.1126/science.2903551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner J, Tauc L. Habituation at the synaptic level in Aplysia. Nature. 1966;210:37–39. doi: 10.1038/210037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JH. Analysis of synaptic depression contributing to habituation of gill-withdrawal reflex in Aplysia californica. J Neurophysiol. 1982;48:431–438. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carew TJ, Kandel ER. Acquisition and retention of long-term habituation in Aplysia: correlation of behavioral and cellular processes. Science. 1973;182:1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.182.4117.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci V, Pinsker H, Kupfermann I, Kandel ER. Neuronal mechanisms of habituation and dishabituation of the gill-withdrawal reflex in Aplysia. Science. 1970;167:1745–1748. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3926.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellucci VF, Kandel ER. A quantal analysis of the synaptic depression underlying habituation of the gill-withdrawal reflex in Aplysia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974;71:5004–5008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.12.5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cens T, Rousset M, Leyris JP, Fesquet P, Charnet P. Voltage- and calcium-dependent inactivation in high voltage-gated Ca(2+) channels. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2006;90:104–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TE, Kaplan SW, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. A simplified preparation for relating cellular events to behavior: mechanisms contributing to habituation, dishabituation, and sensitization of the Aplysia gill-withdrawal reflex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2886–2899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02886.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Guerineau NC, Gahwiler BH, Thompson SM. Paired-pulse facilitation and depression at unitary synapses in rat hippocampus: quantal fluctuation affects subsequent release. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;491:163–176. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds B, Klein M, Dale N, Kandel ER. Contributions of two types of calcium channels to synaptic transmission and plasticity. Science. 1990;250:1142–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.2174573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot LS, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Modulation of spontaneous transmitter release during depression and posttetanic potentiation of Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses isolated in culture. J Neurosci. 1994;14:3280–3292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03280.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliot LS, Kandel ER, Siegelbaum SA, Blumenfeld H. Imaging terminals of Aplysia sensory neurons demonstrates role of enhanced Ca2+ influx in presynaptic facilitation. Nature. 1993;361:634–637. doi: 10.1038/361634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzeddine Y, Glanzman DL. Prolonged habituation of the gill-withdrawal reflex in Aplysia depends on protein synthesis, protein phosphatase activity, and postsynaptic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9585–9594. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09585.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farel PB, Thompson RF. Habituation of a monosynaptic response in frog spinal cord: evidence for a presynaptic mechanism. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:661–666. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.4.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes-Davies M, Cuttle MF, Takahashi T. Inactivation of presynaptic calcium current contributes to synaptic depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron. 1998;20:797–807. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost L, Kaplan SW, Cohen TE, Henzi V, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. A simplified preparation for relating cellular events to behavior: contribution of LE and unidentified siphon sensory neurons to mediation and habituation of the Aplysia gill- and siphon-withdrawal reflex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2900–2913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02900.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirardi M, Braha O, Hochner B, Montarolo PG, Kandel ER, Dale N. Roles of PKA and PKC in facilitation of evoked and spontaneous transmitter release at depressed and nondepressed synapses in Aplysia sensory neurons. Neuron. 1992;9:479–489. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90185-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingrich KJ, Byrne JH. Simulation of synaptic depression, posttetanic potentiation, and presynaptic facilitation of synaptic potentials from sensory neurons mediating gill-withdrawal reflex in Aplysia. J Neurophysiol. 1985;53:652–669. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover TD, Jiang X-Y, Abrams TW. Minimal contribution of vesicle depletion to depression at Aplysia sensory neuron synapses as a consequence of univesicular or limited multi-vesicular release. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1999;25:1129. [Google Scholar]

- Gover TD, Jiang XY, Abrams TW. Persistent, exocytosis-independent silencing of release sites underlies homosynaptic depression at sensory synapses in Aplysia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1942–1955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01942.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves PM, Thompson RF. Habituation: a dual process theory. Psychol. Rev. 1970;77:419–450. doi: 10.1037/h0029810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JI. Repetitive Stimulation at the Mammalian Neuromuscular Junction, and the Mobilization of Transmitter. J Physiol. 1963;169:641–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illich PA, Walters ET. Mechanosensory neurons innervating Aplysia siphon encode noxious stimuli and display nociceptive sensitization. J Neurosci. 1997;17:459–469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00459.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XY, Abrams TW. Use-dependent decline of paired-pulse facilitation at Aplysia sensory neuron synapses suggests a distinct vesicle pool or release mechanism. J Neurosci. 1998;18:10310–10319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-24-10310.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelso SR, Ganong AH, Brown TH. Hebbian synapses in hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5326–5330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerchner GA, Nicoll RA. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:813–825. doi: 10.1038/nrn2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoutorsky A, Spira ME. Calcium-activated proteases are critical for refilling depleted vesicle stores in cultured sensory-motor synapses of Aplysia. Learn Mem. 2005;12:414–422. doi: 10.1101/lm.92105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein M, Shapiro E, Kandel ER. Synaptic plasticity and the modulation of the Ca2+ current. J Exp Biol. 1980;89:117–157. doi: 10.1242/jeb.89.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohout SC, Corbalan-Garcia S, Torrecillas A, Gomez-Fernandez JC, Falke JJ. C2 domains of protein kinase C isoforms alpha, beta, and gamma: activation parameters and calcium stoichiometries of the membrane-bound state. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11411–11424. doi: 10.1021/bi026041k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupfermann I, Castellucci V, Pinsker H, Kandel E. Neuronal correlates of habituation and dishabituation of the gill-withdrawal reflex in Aplysia. Science. 1970;167:1743–1745. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3926.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin XY, Glanzman DL. Long-term depression of Aplysia sensorimotor synapses in cell culture: inductive role of a rise in postsynaptic calcium. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2111–2114. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.3.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallart A, Martin AR. The relation between quantum content and facilitation at the neuromuscular junction of the frog. J. Physiol. 1968;196:593–604. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manseau F, Fan X, Hueftlein T, Sossin W, Castellucci VF. Ca2+-independent protein kinase C Apl II mediates the serotonin-induced facilitation at depressed Aplysia sensorimotor synapses. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1247–1256. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01247.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata M, Chen S, Cai D, Glanzman DL. Coinduction of hemisynaptic long-term depression and long-term potentiation in Aplysia. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 2008 335.312. [Google Scholar]

- Mulkey RM, Endo S, Shenolikar S, Malenka RC. Involvement of a calcineurin/inhibitor-1 phosphatase cascade in hippocampal long-term depression. Nature. 1994;369:486–488. doi: 10.1038/369486a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GG, Glanzman DL. Enhancement of sensorimotor connections by conditioning-related stimulation in Aplysia depends upon postsynaptic Ca2+ Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9931–9936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy GG, Glanzman DL. Mediation of classical conditioning in Aplysia californica by long-term potentiation of sensorimotor synapses. Science. 1997;278:467–471. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman ED, Thiels E, Barrionuevo G, Klann E. Long-term depression in the hippocampus in vivo is associated with protein phosphatase-dependent alterations in extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J Neurochem. 2000;74:192–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0740192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis T, Zhang S, Trussell LO. Direct measurement of AMPA receptor desensitization induced by glutamatergic synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7496–7504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-23-07496.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser CL, Hunter W. The extinction of startle responses and spinal reflexes in the white rat. Am J Physiol. 1936;117:609–618. [Google Scholar]

- Pysh JJ, Wiley RG. Synaptic vesicle depletion and recovery in cat sympathetic ganglia electrically stimulated in vivo. Evidence for transmitter secretion by exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 1974;60:365–374. doi: 10.1083/jcb.60.2.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman RS, Silinsky EM. ATP released together with acetylcholine as the mediator of neuromuscular depression at frog motor nerve endings. J Physiol (Lond) 1994;477:117–127. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JK, Kaun KR, Chen SH, Rankin CH. GLR-1, a non-NMDA glutamate receptor homolog, is critical for long-term memory in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9595–9599. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09595.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Clements JD, Westbrook GL. Nonuniform probability of glutamate release at a hippocampal synapse. Science. 1993;262:754–757. doi: 10.1126/science.7901909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenmund C, Stevens CF. Definition of the readily releasable pool of vesicles at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 1996;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer S, Coulson RL, Klein M. Switching off and on of synaptic sites at aplysia sensorimotor synapses. J Neurosci. 2000;20:626–638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00626.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch S, Castillo PE, Jo T, Mukherjee K, Geppert M, Wang Y, Schmitz F, Malenka RC, Sudhof TC. RIM1alpha forms a protein scaffold for regulating neurotransmitter release at the active zone. Nature. 2002;415:321–326. doi: 10.1038/415321a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrington CS. The Integrative Action of the Nervous System. NY: Charles Scribner's Sons; 1906. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Tsujimoto T. Estimates for the pool size of releasable quanta at a single central synapse and for the time required to refill the pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:846–849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Wesseling JF. Activity-dependent modulation of the rate at which synaptic vesicles become available to undergo exocytosis. Neuron. 1998;21:415–424. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Bagnall MW, Sharma SK, Shobe J, Carew TJ. Intermediate-term memory for site-specific sensitization in Aplysia is maintained by persistent activation of protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3600–3609. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1134-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavalin SJ, Colledge M, Hell JW, Langeberg LK, Huganir RL, Scott JD. Regulation of GluR1 by the A-kinase anchoring protein 79 (AKAP79) signaling complex shares properties with long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3044–3051. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thies RE. Neuromuscular depression and the apparent depl3etion of transmitter in mammalian muscle. J. Neurophysiol. 1965;28:427–442. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RF, Spencer WA. Habituation: a model phenomenon for the study of neuronal substrates of behaviour. Psychol. Rev. 1966;73:16–43. doi: 10.1037/h0022681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Matthews G. Depletion and replenishment of vesicle pools at a ribbon-type synaptic terminal. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1919–1927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-01919.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gersdorff H, Schneggenburger R, Weis S, Neher E. Presynaptic depression at a calyx synapse: the small contribution of metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8137–8146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Bruner J. Long-lasting depression and the depletion hypothesis at crayfish neuromuscular junctions. J. Comp. Physiol. 1977;121:223–240. [Google Scholar]