Abstract

Major trauma increases vulnerability to systemic infections due to poorly defined immunosuppressive mechanisms. It confers no evolutionary advantage. Our objective was to develop better biomarkers of post-traumatic immunosuppression (PTI) and to extend our observation that PTI was reversed by anti-coagulated salvaged blood transfusion, in the knowledge that others have shown that non-anti-coagulated (fibrinolysed) salvaged blood was immunosuppressive.

A prospective non-randomized cohort study of patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty included 25 who received salvaged blood transfusions collected post-operatively into acid–citrate–dextrose anti-coagulant (ASBT cohort), and 18 non-transfused patients (NSBT cohort). Biomarkers of sterile trauma included haematological values, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), cytokines and chemokines. Salvaged blood was analysed within 1 and 6 h after commencing collection. Biomarkers were expressed as fold-changes over preoperative values. Certain biomarkers of sterile trauma were common to all 43 patients, including supranormal levels of: interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1-receptor-antagonist, IL-8, heat shock protein-70 and calgranulin-S100-A8/9. Other proinflammatory biomarkers which were subnormal in NSBT became supranormal in ASBT patients, including IL-1β, IL-2, IL-17A, interferon (IFN)-γ, tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and annexin-A2. Furthermore, ASBT exhibited subnormal levels of anti-inflammatory biomarkers: IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13. Salvaged blood analyses revealed sustained high levels of IL-9, IL-10 and certain DAMPs, including calgranulin-S100-A8/9, alpha-defensin and heat shock proteins 27, 60 and 70. Active synthesis during salvaged blood collection yielded increasingly elevated levels of annexin-A2, IL-1β, Il-1-receptor-antagonist, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-17A, IFN-γ, TNF-α, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α. Elevated levels of high-mobility group-box protein-1 decreased. In conclusion, we demonstrated that anti-coagulated salvaged blood reversed PTI, and was attributed to immune stimulants generated during salvaged blood collection.

Keywords: arthroplasty, cytokines, DAMPs, post-traumatic immunosuppression, sterile trauma

Introduction

In 1856 Florence Nightingale drew attention to the ‘utter insignificance’ of risk of dying from battle wounds acquired during the Crimean War compared with the subsequent risk of dying from zymotic (infectious) diseases [1]. Since then, improvements in hospital hygiene have reduced combat deaths from infectious disease, but an equivalent phenomenon persists [2,3]. Sterile trauma due to major surgery or closed injury increases vulnerability to pneumonia, urinary infection, alimentary infection, sepsis and multi-organ failure, and these outcomes are exacerbated by haemorrhage, transfusion and ageing [4–9].

Vulnerability is attributed to suppression of immunity via multiple pathways, whose natures are only partially understood. Ischaemic and necrotic tissues release anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory and tissue regenerative molecules known as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) [10]. These trigger a ‘genomic storm’ dominated by increased expression of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1-receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), IL-8 (IL-8/CXCL8) and macrophage chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL-2) [11]; mediators that mobilize neutrophil, monocyte and mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC) traffic [12–15]. IL-6 acts via both the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis to increase corticosteroid production and hepatocytes to initiate the acute phase response typified by increased activated protein-C [16]. Meanwhile, IL-1RA neutralizes IL-1β [17].

Both sterile and infected trauma induce the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), originally defined by pyrexia, tachycardia, hyperventilation and neutrophilia, the latter responding poorly to pathogens [18,19]. Accompanying these changes is a decrease in circulating basophil, eosinophil and natural killer precursors (NKp), which further weakens systemic immunity [20]. Sterile SIRS is clinically indistinguishable from infected SIRS, but differences exist in their gene expression profiles [21].

Multiple mechanisms that suppress systemic immunity which, in moments of crisis, would have conferred no evolutionary advantage other than to assist regeneration by avoiding unrestrained activation of tissue destructive inflammatory cascades. Post-traumatic immunosuppression (PTI) could thus have evolved as a non-adaptive consequence of healing [22].

Knee arthroplasty offered an opportunity to characterize PTI in terms of post-operative depression of NKp cells. This was exacerbated by allogeneic or pre-deposited autologous blood transfusions. However, reinfusion of unwashed anti-coagulated salvaged blood caused NKp cells to rise above preoperative levels, accompanied by enhanced interferon (IFN)-γ synthesis and macrophage activation, suggesting that PTI had been reversed [20,23]. This was supported by studies from others showing enhanced post-operative immunity following reinfusion of fresh anti-coagulated autologous blood [24,25].

In contrast, others showed that non-anti-coagulated salvaged blood conferred no change in blood levels of NK cells, albeit identified by the CD56+CD16+ phenotype using flow cytometry and suppression of immune status [26–28]. Our NKp cell subset would have been negative for CD16, and only measurable by limiting dilutions analysis at levels well below detection by routine flow cytometry [29–31].

In this study we have extended our original work by defining PTI in terms of haematological, DAMP, chemokine and cytokine biomarkers. Our results confirmed our observation that anti-coagulated salvaged blood reverses PTI through immune stimulatory properties acquired ex vivo during its collection.

Materials and methods

Study design

This prospective, non-randomized, cohort study was approved by the Southmead Hospital Research Ethics Committee on 9 March 2010 (ref. no. 10/H0102/8). Between 2010 and 2011 a total of 43 patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty at Avon Orthopaedic Centre, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, were recruited after giving written consent. Exclusion criteria included revision arthroplasty, pre-existing infections, previous blood transfusion, malignant disease, non-quiescent autoimmune disorders and diabetes. Study patients had the following characteristics: 70% were female and 30% male; median age was 74 (56–86) years; primary diagnosis was osteoarthritis (41), quiescent rheumatoid arthritis (one) or quiescent psoriatic arthritis (one) and median hospital stay was 4 (3–7) days. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) were given preoperatively to seven patients. Study size was determined by our previous observation that 39 of 40 patients who received salvaged blood showed evidence of reversal of PTI. Arthroplasty was performed under tourniquet. Assignment to the study cohorts was determined by the volume of blood drained from the wound site within the first 6 h after surgery. If total fluid volume accumulated within 6 h was greater than 175 ml it was reinfused; lesser volumes and any fluid salvaged beyond 6 h was discarded. No study patient received allogeneic or autologous pre-deposited blood transfusions. Those 25 patients who received autologous salvaged blood were termed the ASBT cohort, the median transfused volume at 6 h after surgery being 360 (175–550) ml. For comparison, 18 patients received no salvaged blood transfusions and were termed the NSBT cohort. Blood samples for analyses were obtained pre- and post-operatively (Fig. 1). Similar to our previous study, all patients had a subcutaneous drain inserted into their wound site which was attached to a Dideco-797 Recovery Device (Sorin Group Ltd, Milan, Italy) through which negative pressure was applied [20].

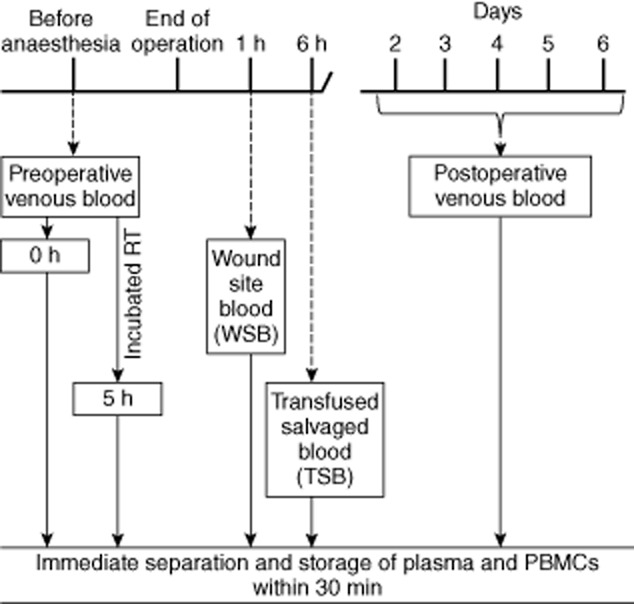

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of blood sample collection time-points. Pre- and post-operative venous blood samples were collected from patients and separated into plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and cryopreserved within 30 min. Half of the preoperative blood sample was incubated at room temperature for 5 h then separated and stored. Salvaged blood samples [wound site blood (WSB) and transfused salvaged blood (TSB)] were collected at 1 and 6 h after surgery, respectively. Details are in the Methods section.

Fluid was collected via the drain tube under constant negative pressure (–25 mmHg) applied with a rotary pump. A smaller diameter tube was joined by Y connector to the drain at the wound site exit. This second tube delivered anti-coagulant acid–citrate–dextrose (ACD-A) solution (Fenwal Inc., Lake Zurich, IL, USA) from a reservoir at a rate that yielded a final ratio of salvaged blood to ACD-A solution of 12 : 1. ACD-A formulation was: acid citrate monohydrate, 4·0 g; sodium citrate dihydrate, 11·0 g; glucose monohydrate, 12·25 g; total H2O volume, 500 ml; pH 4·7–5·3. After 6 h, or after total volume reached 550 ml, the blood collection bag contents were reinfused via a 40 μm blood transfusion filter (Dideco Micro-40-Goccia; Sorin Group Ltd), without further washing or manipulation.

Blood sample collection and assay

The time-points for collection and processing of blood samples are summarized in Fig. 1. Venous blood samples were collected on two occasions into cell preparation tubes containing sodium citrate (CPT Vacutainer; Becton Dickenson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), the first, immediately before anaesthesia (preoperative sample) and the second between 2 and 6 days after surgery on the day of discharge from hospital (post-operative sample). With the exception of one patient sampled on day 2 and another on day 6, all others were bled between days 3 and 5 (mean 3·5). Two autologous salvaged blood samples were taken: the first within 1 h of surgery, hereafter termed ‘wound site blood’ (WSB), and the second prior to reinfusion at approximately 6 h after surgery, hereafter termed ‘transfused salvaged blood’ (TSB). Within 20–30 min of sampling all bloods were separated into plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Plasma and PBMC were aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Biomarkers were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and flow cytometric bead array (Supporting information, Fig. S1). An automated robotic liquid handling system (JANUS Automated Workstation; Perkin Elmer, Akron, OH, USA) was used to assay cytokines and chemokines by ELISA, thereby minimizing interassay variations and human error. Details of the biomarkers and their properties and numbers of patients assayed for each are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of biomarkers assayed

| Missing values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Name | Properties | NSBT | ASBT |

| Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) | High-mobility group box-1 (HMGB-1)† | Mobilizes immunosuppressive MSCs [13]; suppresses IFN-γ secretion; enhances inhibitory T cells [41]; dampens autoimmunity [41] | 0 | 0 |

| Calgranulin (S-100 A8/A9)† | Anti-microbial; chemotactic for leucocytes; protects against LPS induced septic shock [39] | 0 | 0 | |

| Heat shock proteins†: | Up-regulates IL-10 [42,43]; suppresses IL-1β production [44] | 0 | 0 | |

| HSP-27 | 4 | 3 | ||

| HSP-60 | 1 | 0 | ||

| HSP-70 | ||||

| Alpha-defensin (α-defensin)† | Anti-microbial; increases anti-inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production [40] | 0 | 0 | |

| Annexin-A2† | Induces proinflammatory mediators [55] | 0 | 0 | |

| Chemokines | Interleukin-8 (IL-8/CXCL8)† | Neutrophil recruitment [12] | 0 | 0 |

| Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2)† | Monocyte recruitment [14,56] | 2 | 0 | |

| Macrophage inflammatory protein-1-alpha (MIP-1α/CCL3)† | Recruits immature dendritic cells [56]; induces pyrexia [38] | 0 | 0 | |

| Proinflammatory cytokines | Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β)†‡ | Key mediator of inflammatory responses; essential for resistance against pathogens; exacerbates tissue damage [17] | 0 | 0 |

| Interleukin-2 (IL-2)†‡ | Pleiotropic cytokine driving T cell growth; augments NK cell activity; induces differentiation of Treg cells [57] | 0 | 0 | |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6)†‡ | Proinflammatory if bound to soluble receptor (sIL-6R); anti-inflammatory when in free form [51]; induces corticosteroid production; induces anti-inflammatory acute phase proteins [16] | 0 | 0 | |

| Interleukin-12 protein subunit 70 (IL-12p70)†‡ | Induces IFN-γ production; drives activation and differentiation of T cells [58] | 1 | 4 | |

| Interleukin-17A (IL-17A)‡ | With TNF-α enhances neutrophil chemotaxis [47] | 0 | 2 | |

| Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)‡ | Anti-viral; induces proliferation and differentiation of cytotoxic T cells [59] | 7 | 4 | |

| Tumour necrosis factor – alpha (TNF-α)†‡ | Facilitates extravasation of leucocytes to injury site; synergizes with IL-1β to trigger inflammatory cascades [59] | 2 | 3 | |

| Anti-inflammatory cytokines | Interleukin-4 (IL-4)‡ | Similar functions to IL-13 [60] | 0 | 0 |

| Interleukin-5 (IL-5)‡ | Activates B cells; enhances allergic responses [61] | 0 | 0 | |

| Interkeukin-9 (IL-9)‡ | Activates mast cells; promotes Treg cells; induces TGF-β1 production; suppresses IL-12 [48] | 3 | 4 | |

| Interleukin-10 (IL-10)†‡ | Synergizes with IL-4, IL-13 and TGF-β1 to suppress inflammatory cascades induced by IL-1β and TNF-α [59] | 0 | 0 | |

| Interleukin-13 (IL-13)†‡ | Pleiotrophic cytokine; activates Th2 cells and allergic B cells; potent mediator of tissue fibrosis [60] | 0 | 1 | |

| Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA)† | Blocks activity of IL-1β [17] | 0 | 0 | |

| Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1)† | Inhibits inflammatory cascades [62]; induces IL-9 production by Tcells [48] | 0 | 0 | |

Methods of measuring biomarkers:

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA);

flow-cytometric bead array.

NSBT = non-salvaged blood transfused; ASBT = autologous salvaged blood transfused.

Statistical analysis

Readouts from assays were corrected for dilution factors, and expressed as fold-changes over preoperative blood levels. Thus, for each patient, fold-changes were calculated for biomarkers in post-operative blood, WSB and TSB samples. Pooled results were illustrated as median interquartile range (IQR) in box-and-whisker plots on a log10 scale. Greater than 1 and less than 1 indicated supra- and subnormal values, respectively, compared to baseline preoperative levels. Missing values disqualified individual fold-calculations from inclusion in IQRs, with no attempt being made to insert estimates. Missing fold-values for each biomarker are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Individual variations attributed to genetic polymorphisms [37] were highlighted by plotting post-operative against preoperative values for each patient on a log10/log10 scale (Supporting information, Fig. S2a–d). Similar individual variations were apparent in salvaged blood values. Thus fold-values corrected for variations solely attributable to individual baselines. Analyses were by GraphPad Prism software version 5.0.1. Non-parametric tests were used, including Wilcoxon's test (paired) for preoperative versus post-operative values in NSBT and ASBT; Mann–Whitney U-test (unpaired) for fold-changes in NSBT versus in ASBT; Wilcoxon's test (paired) for comparing WSB and TSB levels with preoperative values and between themselves; and Mann–Whitney U-test (unpaired) to compare fold differences in cytokine production between NSBT and ASBT PBMCs.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics

| NSBT | ASBT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) | 74 (61–86) | 73 (56–86) | |||||

| Gender (male : female) | 5:13 | 8:17 | NSBT and ASBT combined mean-fold change over preop. | ||||

| Hospital stay median days (range) | 4 (4–6) | 5 (3–7) | |||||

| Haematological biomarkers: mean ± s.d. (missing values) | |||||||

| Preoperative | P | Post-operative | Preoperative | P | Post-operative | ||

| RBC (×1012/l) | 4·41 ± 0·55 (0) | *** | 3·54 ± 0·46 (0) | 4·43 ± 0·5 (0) | *** | 3·55 ± 0·44 (0) | 0·80 ± 0·08 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 12·64 ± 1·41 (0) | *** | 10·21 ± 1·14 (0) | 13·48 ± 1·57 (0) | *** | 10·75 ± 1·44 (0) | 0·80 ± 0·08 |

| Haematocrit (Hct) | 0·39 ± 0·04 (0) | *** | 0·31 ± 0·03 (0) | 0·42 ± 0·04 (0) | *** | 0·33 ± 0·04 (0) | 0·79 ± 0·08 |

| Platelet (×109/l) | 269·10 ± 63·53 (0) | ** | 227·78 ± 70·62 (0) | 243·90 ± 57·69 (0) | *** | 189·56 ± 48·69 (0) | 0·80 ± 0·14 |

| WBC (×109/ l) | 7·28 ± 1·38 (0) | *** | 9·30 ± 2·42 (0) | 7·61 ± 2·37 (0) | *** | 9·66 ± 2·30 (0) | 1·31 ± 0·31 |

| Lymphocyte (×109/l) | 1·91 ± 0·75 (0) | *** | 1·09 ± 0·52 (0) | 1·85 ± 0·75 (0) | *** | 1·23 ± 0·51 (0) | 0·64 ± 0·20 |

| Monocytes (×109/l) | 0·61 ± 0·24 (0) | * | 0·99 ± 0·51 (0) | 0·56 ± 0·19 (0) | *** | 1·03 ± 0·30 (0) | 1·84 ± 0·79 |

| Neutrophil (×109/l) | 4·55 ± 0·88 (0) | *** | 7·13 ± 2·09 (0) | 5·00 ± 2·11 (0) | *** | 7·36 ± 2·13 (0) | 1·62 ± 0·52 |

| Eosinophil (×109/l) | 0·19 ± 0·13 (5) | *** | 0·05 ± 0·07 (5) | 0·17 ± 0·11 (7) | *** | 0·06 ± 0·08 (7) | 0·32 ± 0·31 |

| Basophil (×109/l) | 0·04 ± 0·03 (1) | *** | 0·019 ± 0·01 (1) | 0·03 ± 0·01 (4) | *** | 0·015 ± 0·01 (4) | 0·55 ± 0·27 |

*P ≤ 0·05 **P ≤ 0·001 ***P ≤ 0·0001. NSBT = non-salvaged blood transfused; ASBT = autologous salvaged blood transfused; s.d. = standard deviation; RBC = red blood celLS; WBC = white blood cells; s.d. = standard deviation.

Results

Patients' characteristics

There were no differences between the NSBT and ASBT cohorts for age, gender and length of hospital stay (Table 2). For all biomarkers analysed no differences were found that were attributable to gender, diagnosis, NSAIDs and age. No significant correlations were found between fold-values and post-operative day of blood sampling (Supporting information, Table S4c). Individual preoperative biomarker (i.e. baseline) levels differed by several orders of magnitude between patients, but trends in post-operative blood values were consistent across groups when values were expressed as fold-changes over preoperative levels (Supporting information, Fig. S2). Thus, major changes were revealed between NSBT and ASBT cohorts (Figs 2 and 3) and between WSB and TSB samples (Figs 4 and 5). In the ASBT cohort no significant correlations were observed between fold-values and volume of blood salvaged (Supporting information, Table S4a,b). There were no post-operative infections or wound-healing problems in any patient, and no significant differences were observed between ASBT and NSBT cohorts in other clinical outcome measures.

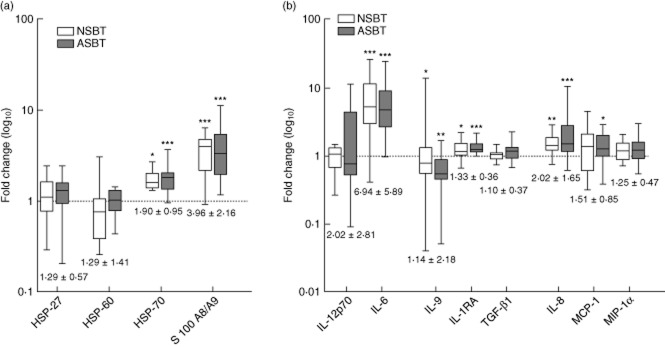

Fig. 2.

Common biomarkers of sterile trauma. Levels of biomarkers are plotted on a log10 scale as median interquartile range (IQR) of fold-changes relative to preoperative values for non-salvaged blood transfused (NSBT) ( ) and autologous salvaged blood transfused (ASBT) (

) and autologous salvaged blood transfused (ASBT) ( ) cohorts: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs); (b) cytokines and chemokines. Combined mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box. Significance of differences between post-operative and preoperative values are represented by *. Thus: *P < 0·05; **P < 0·001 and ***P < 0·0001.

) cohorts: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs); (b) cytokines and chemokines. Combined mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box. Significance of differences between post-operative and preoperative values are represented by *. Thus: *P < 0·05; **P < 0·001 and ***P < 0·0001.

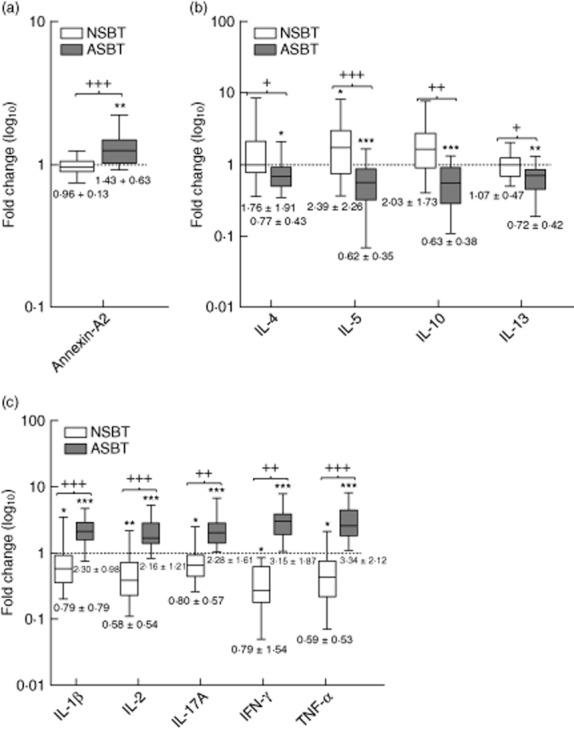

Fig. 3.

Salvaged blood sensitive biomarkers of sterile trauma. Levels of biomarkers are plotted on a log10 scale as median interquartile range (IQR) of fold-changes relative to preoperative values for non-salvaged blood transfused (NSBT) ( ) and autologous salvaged blood transfused (ASBT) (

) and autologous salvaged blood transfused (ASBT) ( ) cohorts. Mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) Annexin-A2; (b) anti-inflammatory cytokines; (c) proinflammatory cytokines. Significance of differences between preoperative and post-operative values are represented by * and differences between NSBT and ASBT cohort fold-values are represented by +. Thus: */+P < 0·05; **/++P < 0·001 and ***/+++P < 0·0001.

) cohorts. Mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMP) Annexin-A2; (b) anti-inflammatory cytokines; (c) proinflammatory cytokines. Significance of differences between preoperative and post-operative values are represented by * and differences between NSBT and ASBT cohort fold-values are represented by +. Thus: */+P < 0·05; **/++P < 0·001 and ***/+++P < 0·0001.

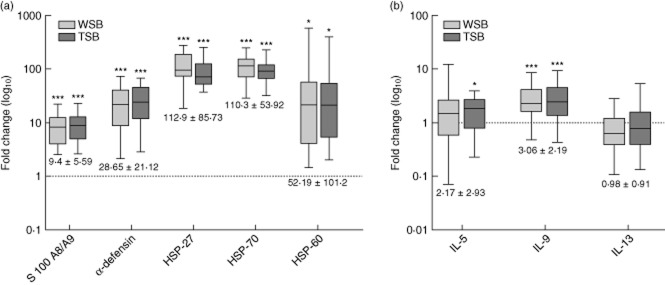

Fig. 4.

Stable biomarkers in salvaged blood. Levels are plotted on a log10 scale as median interquartile range (IQR) of fold-changes relative to preoperative values for wound site blood (WSB) ( ) and transfused salvaged blood (TSB) (

) and transfused salvaged blood (TSB) ( ). Combined mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and (b) cytokines. Significance of differences between WSB or TSB and preoperative values are represented by *. Thus: *P < 0·05; **P < 0·001 and ***P < 0·0001.

). Combined mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and (b) cytokines. Significance of differences between WSB or TSB and preoperative values are represented by *. Thus: *P < 0·05; **P < 0·001 and ***P < 0·0001.

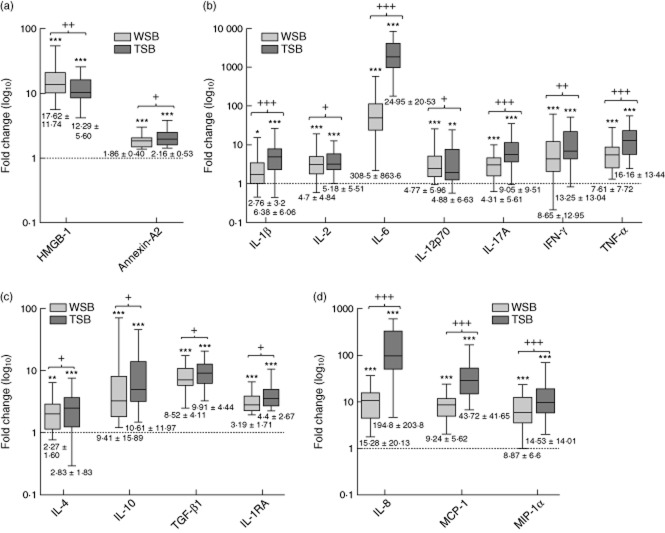

Fig. 5.

Dynamic biomarkers in salvaged blood. Levels are plotted on a log10 scale as median interquartile range (IQR) of fold-changes relative to preoperative values for wound site blood (WSB) ( ) and transfused salvaged blood (TSB) (

) and transfused salvaged blood (TSB) ( ). Mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) high mobility group box protein-1 (HMGB-1) and annexin-A2, (b) proinflammatory cytokines, (c) anti-inflammatory cytokines and (d) chemokines. Significance of differences between preoperative and WSB or TSB values are represented by *, and differences between WSB and TSB fold-values are represented by +. Thus: */+P < 0·05; **/++P < 0·001 and ***/+++P < 0·0001.

). Mean fold-changes ± standard deviation are beneath each box: (a) damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) high mobility group box protein-1 (HMGB-1) and annexin-A2, (b) proinflammatory cytokines, (c) anti-inflammatory cytokines and (d) chemokines. Significance of differences between preoperative and WSB or TSB values are represented by *, and differences between WSB and TSB fold-values are represented by +. Thus: */+P < 0·05; **/++P < 0·001 and ***/+++P < 0·0001.

Common biomarkers of sterile trauma

Biomarkers of sterile trauma (BST) were divisible into two groups, the first of which were common to all patients, and the second of which were altered significantly after anti-coagulated salvaged blood reinfusion. All patients in the NSBT and ASBT cohorts showed similar post-operative trends in the haematological biomarkers (an exception being NKp cell levels published elsewhere [20]). These included above-normal levels of neutrophils and monocytes and subnormal levels of lymphocytes, eosinophils, basophils, platelets and red blood cells (Table 2). All patients exhibited increases in the DAMPs, heat shock protein (HSP)-70 and S100A8/9 (Fig. 2a). All patients exhibited increases in the cytokines IL-6 and IL-1RA and in the chemokine IL-8/CXCL8 (Fig. 2b). No changes were detected in post-operative levels of HSP-27, HSP-60, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α/CCL3 and IL-12p70 (Fig. 2a,b). Combined mean fold-changes for all these biomarkers are documented in Fig. 2, and separate means for NSBT and ASBT cohorts are shown in Supporting information, Table S1.

Salvaged blood sensitive biomarkers of sterile trauma

Certain BST that were either supranormal, normal or subnormal in the NSBT cohort were changed significantly in the ASBT cohort. These included the DAMP–annexin-A2, which was normal in the NSBT but above normal in the ASBT cohort (Fig. 3a). The key anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13, were normal in the NSBT cohort and IL-5 was above normal, whereas in the ASBT cohort they were all subnormal (Fig. 3b). The key proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-17A, IFN-γ and TNF-α, were subnormal in the NSBT cohort, but markedly supranormal in the ASBT cohort (Fig. 3c). Mean fold-changes [± standard deviations (s.d.)] are summarized separately for NSBT and ASBT cohorts in Fig. 3 (see also Supporting information, Table S2).

Characteristics of salvaged blood

Elevated levels of 22 of 24 biomarkers were observed in salvaged blood when expressed as fold-changes over preoperative levels. Exceptions were IL-13 and IL-5, which remained equivalent to normal preoperative levels (Fig 4). Comparisons between WSB and TSB values allowed biomarkers of the salvaged blood transfusion effect to be divided into those that remained unchanged, termed ‘stable biomarkers’, and those whose levels increased during the collection period, termed ‘dynamic biomarkers’.

Stable biomarkers were assumed to have been synthesized continuously by necrotic tissue within the wound site rather than in the collection bag. These were exemplified by massive and sustained fold-increases in S100-A8/9, α-defensin, HSP-27, HSP-60 and HSP-70 (Fig. 4a), and modest increases in IL-9 (Fig 4b). Mean fold-changes for stable biomarkers are documented in Fig. 4, and separately for WSB and TSB samples in Supporting information, Table S3.

Dynamic biomarkers were assumed to have increased through continuous synthesis within the bag during collection. These were illustrated by comparing fold-increases in TSB with fold-increases in WSB. Thus significant elevation was observed in annexin-A2, which increased further, and HMGB-1, which was initially elevated, decreased (Fig. 5a). The proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-17A, IFN-γ and TNF-α, were significantly above normal in WSB and increased further in TSB (Fig. 5b). Similarly, the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4, IL-10, IL-1RA and TGF-β1, were above normal in WSB and increased further in TSB (Fig. 5c). The chemokines IL-8/CXCL8, MCP-1/CCL2 and MIP-1α/CCL3 were above normal in the WSB and also increased substantially in TSB (Fig. 5d). Mean fold-changes (± s.d.) are summarized separately for WSB and TSB in Fig. 5 (see also Supporting information, Table S3).

Discussion

We analysed the haematological, immunological and molecular biomarker profiles of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty [32], which offered a clinical model for studying PTI. Previous reports were either multi-centre studies of patients following diverse incidents of trauma [11] or studies using alternative blood collection procedures [26–28,33–35]. Major features of PTI included subnormal levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-2, IL-17A, IFN-γ and TNF-α, a picture that was reversed dramatically by salvaged blood. Lesser features of PTI included normal levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13, but these were reduced to subnormal levels by salvaged blood. Other biomarkers of sterile trauma, including supranormal levels of HSP-70, S100-A8/A9, IL-6, IL-1RA and IL-8, remained unchanged after salvaged blood transfusion.

The size and non-randomized prospective cohort design of this study was dictated by our previous assumption that reinfusion of unwashed salvaged blood was beneficial, and that to deny this benefit by randomizing patients in advance to a non-transfusion group would have been unethical. Notwithstanding the blood processing device manufacturers' advocacy of the need to wash salvaged blood cells before reinfusion to remove inflammatory and immunomodulatory contaminants [33,36], unwashed salvaged blood conservation is widely practised in arthroplasty, albeit with fibrinolysed blood. This study was not designed to evaluate different salvaging procedures, effects of blood loss or duration of surgery on immune status. Theoretically, randomization would have avoided potential bias due to the extent of post-operative bleeding, but in the event no correlation was observed between biomarker profiles and salvaged blood volume (Supporting information, Table S4a,b). Wide individual variations in preoperative biomarker levels (Supporting information, Fig. S2a–d) were attributable to gene promoter polymorphisms, but we were unable to show that these differences contributed to PTI, as trends expressed as fold-changes were consistent within each patient [37]. Lack of correction for individual variations in studies by others may have reduced sensitivity of analyses [26–28].

Constituents of salvaged blood that were assumed to have originated from surgically induced necrotic and ischaemic tissues were called stable biomarkers, and these included S100 A8/A9, α-defensin, HSP-27, HSP-70, HSP-60 and IL-9. Other constituents, called dynamic biomarkers, increased during collection due to ex-vivo synthesis, and included all three chemokines, all proinflammatory cytokines and the four anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-4, IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1RA. Some of these constituents may have triggered the systemic response to trauma. Thus, increased DAMPs and chemokines would have accounted for the neutrophilia, monocytosis and pyrexia encompassed within the SIRS tautology; however, our overall findings were more consistent with an anti-inflammatory status throughout [12,18,38–40].

Our data could be interpreted according to the following sequence of events. At the wound site, necrotic and ischaemic tissues secreted DAMPs, such as α-defensin, which induced viable cells to synthesize IL-6, IL-8/CXCL8, IL-10, MCP-1/CCL2 and MIP-1α/CCL3 [40]. Simultaneously, HMGB-1 enhanced IL-10 synthesis and recruited immature MSC to the wound site, suppressing major proinflammatory pathways en passant [13,15,41]. High levels of calgranulin-S100A8/A9 acted as chemoattractant for leucocytes and as an important regulator of inflammation, whose synthesis is enhanced by IL-17A [39]. The heat shock proteins, HSP-27, HSP-60 and HSP-70, interacted with dendritic cells, monocytes and MSC to induce IL-10 synthesis [42,43]; furthermore, activation of the HSP gene (HSF1) would have repressed transcription of IL-1β in the wound site [44]. In short, we propose that sterile trauma induced a DAMP-driven anti-inflammatory milieu, reinforced by IL-6, IL-9, IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1RA, whose primary function was to suppress activation of tissue damaging inflammatory cascades, while simultaneously facilitating tissue regeneration by inducing the chemokines IL-8/CXCL8, MCP-1/CCL2 and MIP-1α/CCL3. This sterile trauma induced anti-inflammatory/pro-regenerative paradigm was supported by other endotoxin-free in-vitro models of sterile inflammation [45,46].

Known pleiotrophy of certain cytokines in salvaged blood, such as IL-17A, IFN-γ and TNF-α, could have facilitated regenerative rather than proinflammatory processes, as they would have facilitated synthesis of the chemokines MCP-1/CCL2, MIP-1α/CCL3 and IL-8/CXCL8 [47]. Moreover, IL-9 and IL-10 would have facilitated wound healing by suppressing autoinflammatory reactions and excessive scarring [48–50].

Dynamic biomarkers in salvaged blood included IL-6, which may function either as a pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokine. When bound to its soluble receptor (sIL-6R), the IL-6/sIL-6R complex triggers proinflammatory cascades via a trans-signalling pathway involving ubiquitous gp130 receptors, but when IL-6 binds directly to its receptor (IL-6R) on cell membranes of hypothalamic–pituitary and hepatic cells it triggers anti-inflammatory cascades [51]. Subsequent studies of sIL-6R levels suggested that IL-6 in post-operative venous blood was mostly unbound, but this observation is awaiting further biochemical confirmation.

During 6 h of collection, cells within salvaged blood were subjected to stress by a combination of negative pressure (–25 mmHg), Ca2+ and Mg2+ depletion, plasma dilution, reduced temperature, surface contact with synthetic materials, hypoxia and proteolysis [22]. Simple ex-vivo dilution of whole blood triggers synthesis of inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β and TNF-α [52]. Ca2+ and Mg2+ depletion enhances production of IL-6, IL-1β, IL-12p70 and other proinflammatory cytokines [53,54]. In combination, these stresses facilitated synthesis of dynamic biomarkers as exemplified by rapidly increasing IL-6 (from ×193 to ×1559-fold), IL-8/CXCL8 (from ×10 to ×122-fold), MCP-1/CCL2 (from ×6 to ×27-fold) and MIP-1α/CCL3 (from ×6 to ×9-fold). Simulation experiments using normal preoperative venous blood freshly drawn into ACD and incubated under similar conditions in the laboratory for 5 h suggested that normal blood so treated showed increased synthesis of all proinflammatory markers and selected DAMPs (HSP-60, HSP-70 and annexin-A2), with no increase in anti-inflammatory markers or chemokines (Supporting information, Fig. S3). Our observation that IL-1β was synthesized during collection of salvaged blood is consistent with the work of others [34]. IL-1β is a key initiator of several inflammatory cascades, and would have helped to tip the balance from an anti-inflammatory to a proinflammatory cocktail [17]. Both known and unknown molecular structures within this cocktail are currently under investigation using proteomic and functional assays.

Regarding the target sites for these key intermediaries, we showed that PBMC collected post-operatively from NSBT patients and cultured with a typical bacterial endotoxin, namely lipopolysaccharide (LPS), responded by synthesizing anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10, TGF-β and IL-1RA. In contrast, PBMC from ASBT patients produced no increase in these anti-inflammatory cytokines, implying that PTI was due in part to impaired functional capacity of immune cells against bacteria, and that anti-coagulated salvaged blood transfusion abrogated this effect (Supporting information, Fig. S4). This finding contrasted with observations by others (vide infra) [28].

In this present study a distinction emerged between common BST and salvaged blood sensitive BST. Whereas common BST were observed in all patients irrespective of reinfusion, salvaged blood sensitive BST were profoundly altered after reinfusion. An unresolved paradox is that certain anti-inflammatory biomarkers, namely HSP-70, S100-A8/9, IL-6 and IL-1RA, co-existed in ASBT patients with the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-2, IL-17A, IFN-γ and TNF-α. In this context, the pro/anti-inflammatory paradigm needs to be nuanced to accommodate these complexities. One hypothesis is that salvage blood sensitive BST reflect evolutionarily redundant changes that account for PTI that are amenable to therapeutic intervention without jeopardizing tissue regeneration.

In apparent contrast to our findings, others investigated effects of non-anti-coagulated salvaged blood and demonstrated either no change in immune status or immunosuppression [26–28,35]. No differences in post-operative NK cell levels were observed, (vide supra) and endotoxin challenge studies implied an immunosuppressive response, typified by increased IL-10 and decreased TNF-α. These differences need to be resolved by future randomized studies to compare the two methods of salvaging blood.

Notwithstanding these differences, we clearly observed enhanced immune status as exemplified by supranormal levels of functionally active NKp cells, increased IFN-γ synthesis and increased activation of macrophages (Supporting information, Fig. S5) [20]. In this study, these changes are shown to be accompanied by increases in the proinflammatory biomarkers annexin-A2, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-17A, IFN-γ and TNF-α, and decreases in the anti-inflammatory biomarkers IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13. Future manipulation of immune status using purified derivatives of anti-coagulated salvaged blood may reduce vulnerability to infection after major surgery or injury, but fine-tuning of inflammatory cascades could also risk triggering inflammatory diseases. These and other speculations remain to be evaluated in future clinical follow-up studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Matthew Griffin MBBCh, MD, REMEDI, NUI Galway, for valuable comments and discussions. We thank Professor Corrado Santocanale PhD, DSc, National Centre of Biomedical Engineering Science (NCBES), Galway, for help with Perkin Elmer Automated Liquid Handling. We thank Mr Claas Baustian BSc, MSc and Dr Shirley Hanley BSc, MSc, PhD, Flow Cytometry Core Facility, NUI Galway for training in the use of Accuri-C6 flow cytometer. We acknowledge the following funding sources: Institutes of Technology Ireland – TSR Award (TSR/2008/TL13) provided a scholarship for N. I. to complete the award of MSc by Research; Irish Research Council – EMBARK Award (RS/2011/223) provided a scholarship to support N. I.'s PhD studies; Programme for Research in Third level Institutions-5 – Advancing Medicines Programme funded the core facility at NUIG for automatic liquid handling technology and support; Science Foundation Ireland (SFI09/SRC/B1794) provided additional resources for laboratory assays; and Bristol Orthopedic Trust funded resources for carrying out clinical protocols and sample collection. Finally, this work was supported by Science foundation Ireland under grant numbers SFI PI 06/1N.1/B652 (M. D. G.) and SFI09/B1794 (R. C. and M. D. G.) and by a Science Foundation Ireland Stoke's Professorship SFI07/SK/B1233b (R. C.)

Author contributions

B. B. was the principle investigator and originator of this study. B. B., N. I., G. B., A. B. and M. W. designed the study. M. W., G. B., A. B. and S. M. organized patient recruitment and administered the surgical and post-operative treatment protocol. N. I. collected, processed and preserved all blood samples and conducted all laboratory assays. E. O. C. and N. I. developed and optimized automated ELISA assays. B. B., M. H., J. T. and R. C. supervised and guided laboratory studies. J. H was responsible for statistical analysis of data. B. B., R. C. and N. I. interpreted data. B. B., N. I. and R. C. wrote the manuscript and all authors saw and approved the final version of the manuscript. These results form part of NI's submission for awards of MSc and PhD. B. B. and M. H. jointly supervised N. I. for award of MSc by Research at IT Tralee in 2011. B. B. and R. C. are currently jointly supervising N. I. for the award of PhD at NUI Galway.

Competing interests

There were no competing interests by any of the co-authors.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Fig. S1. Gating strategy for flow cytometric bead array technique.

Fig. S2. Individual variation in anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory cytokines.

Fig. S3. Simulated salvaged blood results.

Fig. S4. Cytokine profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) challenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Fig. S5. Neopterin levels after salvaged blood reinfusion.

Table S1. Common biomarkers of sterile trauma

Table S2. Salvage blood sensitive biomarkers of sterile trauma

Table S3. Constituents of salvaged blood at 1 h [wound site blood (WSB)] and 6 h [transfused salvaged blood (TSB)] after surgery

Table S4. Correlation between biomarker levels, length of hospital stay, volume of blood drained and volume of blood transfused

References

- 1.Nightingale F, Nightingale FNoh. Florence Nightingale: measuring hospital care outcomes: excerpts from the books Notes on matters affecting the health, efficiency, and hospital administration of the British army founded chiefly on the experience of the late war, and Notes on hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CK, Hinkle MK, Yun HC. History of infections associated with combat-related injuries. J Trauma. 2008;64:S221–231. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318163c40b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smallman-Raynor MR, Cliff AD. Impact of infectious diseases on war. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004;18:341–368. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostendorf U, Ewig S, Torres A. Nosocomial pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:327–338. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000235158.40184.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halleberg Nyman M, Johansson JE, Persson K, Gustafsson M. A prospective study of nosocomial urinary tract infection in hip fracture patients. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2531–2539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fry DE. Sepsis, systemic inflammatory response, and multiple organ dysfunction: the mystery continues. Am Surg. 2012;78:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shorr AF, Jackson WL. Transfusion practice and nosocomial infection: assessing the evidence. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11:468–472. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000176689.18433.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butcher SK, Killampalli V, Lascelles D, Wang K, Alpar EK, Lord JM. Raised cortisol : DHEAS ratios in the elderly after injury: potential impact upon neutrophil function and immunity. Aging Cell. 2005;4:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villarroel JP, Guan Y, Werlin E, Selak MA, Becker LB, Sims CA. Hemorrhagic shock and resuscitation are associated with peripheral blood mononuclear cell mitochondrial dysfunction and immunosuppression. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75:24–31. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182988b1f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaczmarek A, Vandenabeele P, Krysko DV. Necroptosis: the release of damage-associated molecular patterns and its physiological relevance. Immunity. 2013;38:209–223. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao W, Mindrinos MN, Seok J, et al. Program IaHRtIL-SCR. A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2581–2590. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:159–175. doi: 10.1038/nri3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lotfi R, Eisenbacher J, Solgi G, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells respond to native but not oxidized damage associated molecular pattern molecules from necrotic (tumor) material. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2021–2028. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffin MD, Elliman SJ, Cahill E, English K, Ceredig R, Ritter T. Concise review: adult mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for inflammatory diseases: how well are we joining the dots? Stem Cells. 2013;31:2033–2041. doi: 10.1002/stem.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jawa RS, Anillo S, Huntoon K, Baumann H, Kulaylat M. Analytic review: interleukin-6 in surgery, trauma, and critical care: part I: basic science. J Intens Care Med. 2011;26:3–12. doi: 10.1177/0885066610395678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bone RC. Immunologic dissonance: a continuing evolution in our understanding of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:680–687. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adib-Conquy M, Cavaillon JM. Compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gharehbaghian A, Haque KM, Truman C, et al. Effect of autologous salvaged blood on postoperative natural killer cell precursor frequency. Lancet. 2004;363:1025–1030. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson SB, Lissauer M, Bochicchio GV, Moore R, Cross AS, Scalea TM. Gene expression profiles differentiate between sterile SIRS and early sepsis. Ann Surg. 2007;245:611–621. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251619.10648.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–435. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Islam NWM, Mehandale S, Hall M, Blom A, Bannister G, Bradley B. Neopterin levels confirm immunostimulation by unwashed salvaged blood transfusion. Transfus Alternat Transfus Med. 2011;12:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen G, Zhang FJ, Gong M, Yan M. Effect of perioperative autologous versus allogeneic blood transfusion on the immune system in gastric cancer patients. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007;8:560–565. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan M, Chen G, Fang LL, Liu ZM, Zhang XL. Immunologic changes to autologous transfusion after operational trauma in malignant tumor patients: neopterin and interleukin-2. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2005;6:49–52. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2005.B0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muñoz M, Cobos A, Campos A, Ariza D, Muñoz E, Gómez A. Post-operative unwashed shed blood transfusion does not modify the cellular immune response to surgery for total knee replacement. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006;50:443–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2006.00977.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muñoz M, Cobos A, Campos A, Ariza D, Muñoz E, Gómez A. Impact of postoperative shed blood transfusion, with or without leucocyte reduction, on acute-phase response to surgery for total knee replacement. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:1182–1190. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muñoz M, Muñoz E, Navajas A, Campos A, Rius F, Gómez A. Impact of postoperative unwashed shed blood retrieved after total knee arthroplasty on endotoxin-stimulated tumor necrosis factor alpha release in vitro. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:267–272. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200602000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gharehbaghian A, Haque KM, Truman C, Newman J, Bradley BA. Quantitation of natural killer cell precursors in man. J Immunol Methods. 2002;260:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00534-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mrózek E, Anderson P, Caligiuri MA. Role of interleukin-15 in the development of human CD56+ natural killer cells from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 1996;87:2632–2640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:633–640. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blom AW, Brown J, Taylor AH, Pattison G, Whitehouse S, Bannister GC. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:688–691. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b5.14887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muñoz M, Slappendel R, Thomas D. Laboratory characteristics and clinical utility of post-operative cell salvage: washed or unwashed blood transfusion? Blood Transfus. 2011;9:248–261. doi: 10.2450/2010.0063-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalén T, Bengtsson A, Brorsson B, Engström KG. Inflammatory mediators in autotransfusion drain blood after knee arthroplasty, with and without leucocyte reduction. Vox Sang. 2003;85:31–39. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.2003.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tylman M, Bengtson JP, Avall A, Hyllner M, Bengtsson A. Release of interleukin-10 by reinfusion of salvaged blood after knee arthroplasty. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1379–1384. doi: 10.1007/s001340101025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarbinowski R, Arvidsson S, Tylman M, Oresland T, Bengtsson A. Plasma concentration of procalcitonin and systemic inflammatory response syndrome after colorectal surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:191–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu W, Jiang J. Genetic polymorphisms and posttraumatic complications. Comp Funct Genomics. 2010;2010:814086. doi: 10.1155/2010/814086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soares DM, Figueiredo MJ, Martins JM, et al. CCL3/MIP-1 alpha is not involved in the LPS-induced fever and its pyrogenic activity depends on CRF. Brain Res. 2009;1269:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goyette J, Geczy CL. Inflammation-associated S100 proteins: new mechanisms that regulate function. Amino Acids. 2011;41:821–842. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehrer RI. Multispecific myeloid defensins. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:16–21. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wild CA, Bergmann C, Fritz G, et al. HMGB1 conveys immunosuppressive characteristics on regulatory and conventional T cells. Int Immunol. 2012;24:485–494. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxs051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borges TJ, Wieten L, van Herwijnen MJC, et al. The anti-inflammatory mechanisms of Hsp70. Front Immunol. 2012;3:95. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Eden W, van Herwijnen M, Wagenaar J, van Kooten P, Broere F, van der Zee R. Stress proteins are used by the immune system for cognate interactions with anti-inflammatory regulatory T cells. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1951–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xie Y, Chen C, Stevenson MA, Auron PE, Calderwood SK. Heat shock factor 1 represses transcription of the IL-1beta gene through physical interaction with the nuclear factor of interleukin 6. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11802–11810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savage CD, Lopez-Castejon G, Denes A, Brough D. NLRP3-inflammasome activating DAMPs stimulate an inflammatory response in glia in the absence of priming which contributes to brain inflammation after injury. Front Immunol. 2012;3:288. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li W, Ling HP, You WC, et al. Elevated cerebral cortical CD24 levels in patients and mice with traumatic brain injury: a potential negative role in nuclear factor kappa B/inflammatory factor pathway. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;46:187–198. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffin GK, Newton G, Tarrio ML, et al. IL-17 and TNF-α sustain neutrophil recruitment during inflammation through synergistic effects on endothelial activation. J Immunol. 2012;188:6287–6299. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noelle RJ, Nowak EC. Cellular sources and immune functions of interleukin-9. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nri2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim HS, Chung DH. IL-9-producing invariant NKT cells protect against DSS-induced colitis in an IL-4-dependent manner. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:347–357. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kieran I, Knock A, Bush J, et al. Interleukin-10 reduces scar formation in both animal and human cutaneous wounds: results of two preclinical and phase II randomized control studies. Wound Repair Regen. 2013;21:428–436. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rose-John S. IL-6 trans-signaling via the soluble IL-6 receptor: importance for the pro-inflammatory activities of IL-6. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1237–1247. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pott GB, Chan ED, Dinarello CA, Shapiro L. Alpha-1-antitrypsin is an endogenous inhibitor of proinflammatory cytokine production in whole blood. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:886–895. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0208145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peters LR, Raghavan M. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium depletion impacts chaperone secretion, innate immunity, and phagocytic uptake of cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:919–931. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rayssiguier Y, Mazur A. [Magnesium and inflammation: lessons from animal models] Clin Calcium. 2005;15:245–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Swisher JF, Khatri U, Feldman GM. Annexin A2 is a soluble mediator of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1174–1184. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:313–326. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liao W, Lin JX, Leonard WJ. IL-2 family cytokines: new insights into the complex roles of IL-2 as a broad regulator of T helper cell differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gee K, Guzzo C, Che Mat NF, Ma W, Kumar A. The IL-12 family of cytokines in infection, inflammation and autoimmune disorders. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2009;8:40–52. doi: 10.2174/187152809787582507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dinarello CA. Proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;118:503–508. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wynn TA. IL-13 effector functions. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takatsu K, Kouro T, Nagai Y. Interleukin 5 in the link between the innate and acquired immune response. Adv Immunol. 2009;101:191–236. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)01006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oh SA, Li MO. TGF-β: guardian of T cell function. J Immunol. 2013;191:3973–3979. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Gating strategy for flow cytometric bead array technique.

Fig. S2. Individual variation in anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory cytokines.

Fig. S3. Simulated salvaged blood results.

Fig. S4. Cytokine profiles of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) challenged with lipopolysaccharide (LPS).

Fig. S5. Neopterin levels after salvaged blood reinfusion.

Table S1. Common biomarkers of sterile trauma

Table S2. Salvage blood sensitive biomarkers of sterile trauma

Table S3. Constituents of salvaged blood at 1 h [wound site blood (WSB)] and 6 h [transfused salvaged blood (TSB)] after surgery

Table S4. Correlation between biomarker levels, length of hospital stay, volume of blood drained and volume of blood transfused