A new pH-sensitive red fluorescent protein called pHuji, in combination with green fluorescent superecliptic pHluorin, allows two-color detection of endocytic events in live cells.

Abstract

Fluorescent proteins with pH-sensitive fluorescence are valuable tools for the imaging of exocytosis and endocytosis. The Aequorea green fluorescent protein mutant superecliptic pHluorin (SEP) is particularly well suited to these applications. Here we describe pHuji, a red fluorescent protein with a pH sensitivity that approaches that of SEP, making it amenable for detection of single exocytosis and endocytosis events. To demonstrate the utility of the pHuji plus SEP pair, we perform simultaneous two-color imaging of clathrin-mediated internalization of both the transferrin receptor and the β2 adrenergic receptor. These experiments reveal that the two receptors are differentially sorted at the time of endocytic vesicle formation.

Introduction

Genetically encoded sensors based on fluorescent proteins (FPs) have become essential tools for studying cell physiology. A broad range of FP-based sensors have now been developed to monitor numerous biochemical parameters including Ca2+ concentration (Zhao et al., 2011), membrane potential (Dimitrov et al., 2007), Cl− concentration (Jayaraman et al., 2000), and pH (Miesenböck et al., 1998). For studies of exocytosis and endocytosis, the sensor of choice has been superecliptic pHluorin (SEP), a mutant of enhanced GFP (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2000). With a pKa (i.e., the pH value at which the fluorescence intensity is 50% of maximal) of 7.2, SEP is nearly nonfluorescent at pH 5.5 (the pH of intracellular secretory vesicles and recycling endosomes) but brightly green fluorescent at pH 7.4 (the extracellular pH). The SEP protein, fused to relevant membrane proteins, has been extensively used to detect the exocytosis of synaptic vesicles, secretory vesicles, and recycling endosomes (Sankaranarayanan et al., 2000; Gandhi and Stevens, 2003; Tsuboi and Rutter, 2003; Yudowski et al., 2006; Balaji and Ryan, 2007; Jullié et al., 2014). Moreover, it has been used to detect the formation of clathrin-coated vesicles (CCVs) using the pulsed pH (ppH) protocol (i.e., alternating the extracellular pH between 7.4 and 5.5), which reveals the location of receptors that have been newly internalized with high temporal accuracy (Merrifield et al., 2005).

A red FP with pH dependence similar to SEP would be of great use because it would enable two-color imaging of membrane trafficking events. For example, a red FP pH sensor could be imaged in conjunction with a GFP-tagged protein of interest to analyze the spatial and temporal dynamics of protein recruitment during exocytosis (An et al., 2010) or endocytosis (Taylor et al., 2011). Alternatively, the trafficking of two membrane cargos could be monitored simultaneously to address their differential sorting. Several pH-sensitive orange to red Discosoma red FP–derived variants have been previously described, with pKas ranging from 6.5 for some proteins of the mFruit series (i.e., mOrange, mOrange2, and mApple; Shaner et al., 2004, 2008) to 6.9 for mNectarine (Johnson et al., 2009) and 7.8 for pHTomato (Li and Tsien, 2012). In addition, an excitation ratiometric pH sensor with an apparent pKa of 6.6, designated pHRed, was engineered from the long stokes shift FP mKeima (Tantama et al., 2011).

For practical applications, none of the previously described pH-sensitive red FPs provide in situ pH-dependent changes in fluorescence intensity that are comparable to SEP. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has directly addressed the question of why these red pH sensors have not proven to be as useful as SEP, despite the substantial effort invested in their development. In this work we address this important question and, based on the insights we obtain, engineer a new pH-sensitive red FP. We show here that pHuji, a new red fluorescent pH sensor, can be used in conjunction with SEP for two-color imaging of exocytic and endocytic events. With the combined use of SEP and pHuji, we demonstrate the differential sorting of two receptors, the transferrin receptor (TfR) and the β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR), into individual endocytic vesicles.

Results

Characterization of SEP and previously described red pH sensors

In vitro characterization of the pH dependence of fluorescence demonstrates that SEP is exceptionally well tuned for large fluorescence changes when transitioning between pH 5.5 and 7.5. SEP is almost entirely quenched at pH 5.5 and exhibits an ∼50-fold higher fluorescence intensity at pH 7.5 (Table 1). In contrast, mNectarine and pHTomato only have approximately sixfold and threefold change, respectively, over the same pH range, despite their relatively high pKas of 7.9 and 6.9, respectively (Table 1). This result demonstrates that pKa alone is not sufficient to characterize a pH-sensitive FP.

Table 1.

In vitro characterization of pH-sensitive FPs

| Protein | pKa | nH | Fluorescence fold change (pH 5.5–7.5) | Excitation peak at pH 7.2 | Emission peak at pH 7.2 |

| nm | nm | ||||

| SE-pHluorin | 7.2 | 1.90 | 50 | 495 | 512 |

| mNectarine | 6.9 | 0.78a | 6 | 558 | 578 |

| pHTomato | 7.8 | 0.51a | 3 | 562 | 578 |

| mOrange | 6.5 | 0.77 | 5 | 548 | 562 |

| pHoran1 | 6.7 | 0.87 | 10 | 547 | 564 |

| pHoran2 | 7.0 | 0.89 | 12 | 549 | 563 |

| pHoran3 | 7.4 | 0.87 | 15 | 551 | 566 |

| pHoran4 | 7.5 | 0.92 | 17 | 547 | 561 |

| mCherry-TYG | 7.8 | 0.73a | 5 | 546 | 568 |

| mApple | 6.6 | 0.68 | 4 | 568 | 592 |

| A-9 | 7.4 | 0.73 | 12 | 576 | 596 |

| A-17 | 7.2 | 0.87 | 11 | 576 | 596 |

| A-47 | 7.1 | 0.83 | 10 | 570 | 592 |

| pHuji | 7.7 | 1.10 | 22 | 566 | 598 |

Biphasic titration curve. To obtain the apparent nH, the whole titration curve was fit with a monophasic function.

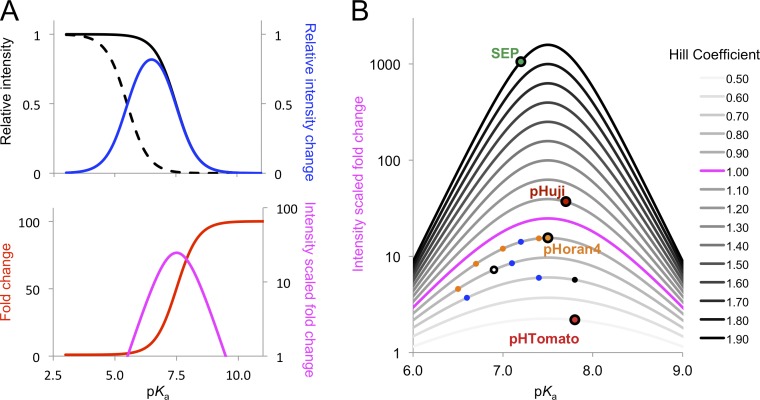

To find the optimal parameters for maximized fluorescence change between pH 5.5 and 7.5, we modeled the theoretical fluorescence changes between these two pH values assuming various pKa values. These calculations revealed that the fluorescence fold change (F7.5/F5.5) increases with increasing pKa (Fig. 1 A, red curve). However, a higher pKa also results in lower brightness of the protein in the physiological pH range (Fig. 1 A, black curves). To account for this limitation, we took the relative fluorescence intensity change, (F7.5 − F5.5)/Fmax, into consideration (Fig. 1 A, blue curve). This value is maximal when pKa = 6.5. Multiplication of the functions for fold change and relative change leads to a new function, termed intensity scaled fold change, which represents the optimal compromise of both fluorescence fold change and overall brightness (Fig. 1 A, magenta curve). This calculation revealed that the optimal theoretical pKa value of a pH-sensitive FP is 7.5.

Figure 1.

Theoretical optimization of pH sensor properties. (A) Theoretical calculation of optimal pKa for the largest fluorescence change from 5.5 to 7.5, with a nH of 1.0. Black solid line, relative fluorescence at pH 7.5 (F7.5/Fmax); black dashed line, relative fluorescence at pH 5.5 (F5.5/Fmax); red line, fluorescence fold change (F7.5/F5.5); blue line, relative fluorescence intensity change ((F7.5-F5.5)/Fmax); magenta line, intensity scaled fold change, which is the multiplication product of fold change and intensity change. (B) Effect of nH on the intensity scaled fold change at different pKa values. The pH-sensitive FPs covered in this work are mapped according to pKa and nH values. From top to bottom (nH descending), right to left (pKa descending): SEP; pHuji; pHoran4 (orange, same as mOrange and mOrange variants), pHoran3, A-17 (blue, same as mApple and mApple variants), pHoran2, and pHoran1; A-47, mNectarine (white), and mOrange; mCherry-TYG (black), A-9, and mApple; and pHTomato.

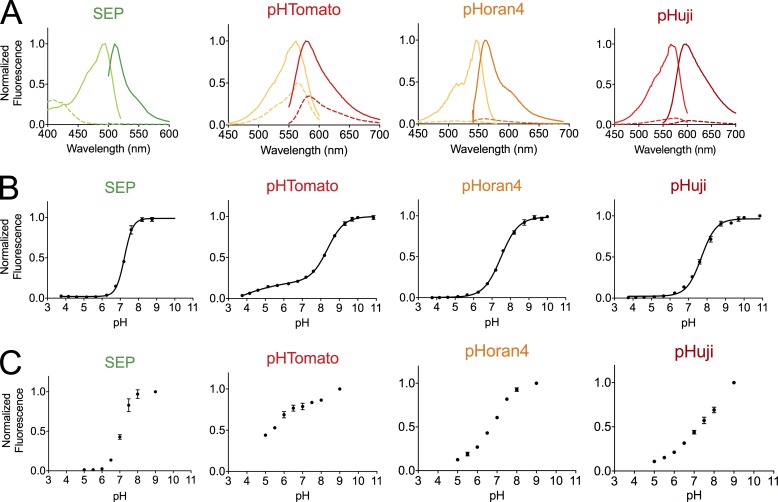

Although SEP, with a pKa of 7.2, is the closest to this ideal value, this factor alone is not sufficient to explain the superior performance of SEP relative to the other variants. It quickly became apparent that an equally important factor in determining the performance of these pH indicators is the slope of the fluorescence versus pH curves, which is determined by the apparent Hill coefficient (nH). Indeed, further modeling revealed that a higher nH provides a substantially larger fluorescence change without changing the optimal pKa value (Fig. 1 B). Curve fitting revealed that SEP has an exceptionally high nH of 1.90. Overall, the excellent performance of SEP is caused by the combination of a nearly optimal pKa and a high nH. In contrast, the nHs of mNectarine and pHTomato are 0.78 and 0.51, respectively (Table 1), which largely explains the relatively modest changes in fluorescence for these proteins between pH 5.5 and 7.5. Moreover, their emission peaks have more than a 15-nm blue shift over the pH range of 5 to 10. In contrast, SEP has a negligible peak shift (Table S1 and Fig. 2 A). These limitations prompted us to look for red FP pH sensors with optimized pKa and nH values as well as good optical characteristics such as a red-shifted emission and little pH-dependent peak shift.

Figure 2.

Spectra and pH titration curves of pH-sensitive FPs. (A) Excitation and emission spectra of pH-sensitive FPs SEP, pHTomato, pHoran4, and pHuji at pH 5.5 (dashed line) and 7.5 (solid line). (B) pH titration curves of the indicated FP. (C) Fluorescence of HeLa cells expressing pDisplay proteins fused to the indicated FP as a function of pH. Error bars represent SEM.

pHorans: pH-sensitive mOrange variants with fine-tuned pKas

As a first step toward developing a second color of pH sensor with optimized pKa and nH, we created a series of orange FPs with pKas that approached the ideal value of 7.5. To achieve this goal, we started with mOrange, a bright FP with a pKa of 6.5 (Shaner et al., 2004). The previously described M163K mutation was introduced to raise the pKa to 7.5 (Shaner et al., 2008). Using mOrange M163K as a template we performed four rounds of random mutagenesis followed by saturation mutagenesis at residues 163 and 161, where beneficial mutations had repeatedly showed up during screening of randomly generated libraries. Both of these residues are in close proximity to the chromophore. Colonies that retained high fluorescent brightness were cultured and the fluorescent brightness of extracted protein was measured at pH 5.5 and 7.5. Two specific mutations, E160K and G196D, which are known to increase the photostability of mOrange (Shaner et al., 2008), were also rationally introduced during the course of development. Library screening led to the identification of three bright variants with pKas of 6.7, 7.0, and 7.4 (Table S2). This series of the pH-sensitive mOrange variants was named pHorans (pH-sensitive orange FPs) 1 to 4 according to their pKa values in ascending order (Table 1). Despite the fact that pHoran4 is remarkably bright (extinction coefficient [EC] of 83,000 M−1cm−1 and quantum yield 0.66) and has a pKa value close to SEP, its fluorescence intensity fold change from pH 5.5 to 7.5 is still significantly smaller than that of SEP (Table 1 and Fig. 2 B) because of its lower nH value of 0.92. Unfortunately, pHoran variants with higher nH values were not identified during exhaustive library screening. Yet another drawback of the pHorans is that their orange fluorescent emission spectra (with emission peaks close to 560 nm) result in substantial spectral bleed-through when combined with SEP for two-color imaging.

We also explored the strategy of modifying the chromophore structure of the red FP mCherry (Shaner et al., 2004). We found that a variant with the threonine–tyrosine–glycine (TYG) chromophore (as in mOrange), designated as mCherry-TYG, has a significantly higher pKa of 7.8 and an apparent nH of 0.73 (Table 1). Because of its pH-dependent emission peak shift (Table S1) and an incomplete quenching at low pH (Fig. S1 A), this variant was not further pursued.

pHuji: a red pH-sensitive FP with near-optimal pKa and a high apparent nH

For our next attempt at developing an improved red pH sensor with an emission peak well separated from that of SEP, we turned to mApple as a template (Shaner et al., 2008). Libraries were constructed by randomizing residues in close proximity to the chromophore, including positions 64, 70, 95, 97, 146, 148, 159, 161, 163, 177, and 197 (numbered according to mCherry crystal structure, PDB ID 2H5Q; Shaner et al., 2004). After initial screening, it was found that positions 161 and 163 were primarily responsible for modulating the pKa of mApple. Accordingly, we constructed a targeted library of variants by saturation mutagenesis of both positions 161 and 163 and screened exhaustively for variants with increased pKa and higher nHs.

Several pH-sensitive variants, including A-9, A-17, and A-47, were identified from the library (Tables 1 and S2). Among them, one variant with a single mutation of K163Y demonstrated the highest pH sensitivity with a pKa of 7.7 and an apparent nH of 1.10. Notably, all of the mApple variants as well as pHoran3 and pHoran4 have essential mutations at position 163, predicted from published mFruit structures (Shu et al., 2006) to be close to the chromophore (Fig. S1, B and C), clearly demonstrating that this residue plays a key role in modulating the pH sensitivity of variants of the Discosoma red FP. Two rounds of random mutagenesis using mApple K163Y as the template did not result in further improvements in pH sensitivity. Accordingly, mApple K163Y was designated as pHuji (pronounced Fuji, a common cultivar of apple). It exhibits relatively bright fluorescence with an EC of 31,000 M−1cm−1 and a quantum yield of 0.22. More importantly, pHuji demonstrates a more than 20-fold fluorescent intensity change from pH 5.5 to 7.5, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the largest reported intensity change for a red FP in this pH range (Table 1 and Fig. 2 B). This is in good accordance with the predictions we could make from its high nH and near-optimal pKa value (Fig. 1 B). Finally, pHuji has an emission peak (598 nm) that shows a negligible pH-dependent shift (Table S1) and is well separated from SEP emission (512 nm; Table 1 and Fig. 2 A). Simultaneous two-color imaging is therefore possible with these two variants.

Characterization and comparison of pH-sensitive FPs in vitro and in situ

Based on the in vitro characterization, we decided to focus on comparing only our best candidates, pHuji and pHoran4, with previously described SEP and pHTomato in living cells. Accordingly, we transfected HeLa cells with the pH-sensitive red FP in the pDisplay vector to anchor them to the cell surface as a fusion to the transmembrane domain of platelet-derived growth factor receptor. These cells were imaged with total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy in buffered solutions ranging from pH 5.0 to 8.9. Similar to the fluorescence measurements obtained for recombinant proteins, SEP fluorescence was completely quenched at pH 5.0 and maximal at pH 8.9, with a 63-fold change in fluorescence between pH 5.5 and 7.5. The pH sensitivity of red FPs in the same context was qualitatively similar to the in vitro data, though their pH sensitivity was somewhat less pronounced than expected. pHTomato was poorly pH sensitive, with less than twofold change in fluorescence between pH 5.5 and 7.5. pHuji and pHoran4 were more strongly pH sensitive with fivefold change over the same pH range (Fig. 2 C). However, pHuji and pHoran4 still retained dim fluorescence even at pH 5.0. This could either be caused by environmental factors that result in different pH sensitivities in vitro compared with in cells or by the presence of a visible intracellular pool of protein that is inaccessible to extracellular pH changes. To test for the latter hypothesis, we first applied a solution containing ammonium chloride (50 mM) to cancel intracellular pH gradients (Miesenböck et al., 1998). This treatment revealed a few intracellular vesicles for all FPs but the overall diffuse fluorescence did not change (Fig. S2, A and B), demonstrating that this diffuse labeling is indeed caused by proteins on the plasma membrane and not in mildly acidic intracellular compartments. However, the residual fluorescence at pH 5.0 could also be caused by a neutral intracellular compartment. Thus, to collapse all ionic gradients, we permeabilized cells with digitonin (50 µg/ml). In these conditions, the fluorescence at pH 5.0 was still 10.0 ± 0.8% (n = 3) and 11.0 ± 0.8% (n = 4) of that at pH 7.4 for pHoran4 and pHuji, respectively, similar to unpermeabilized cells (10.1 ± 2.9% [n = 4] and 11.1 ± 0.7% [n = 5]; Fig. S2, C and D). Therefore, the pDisplay vector correctly anchored the FPs at the plasma membrane, but pHoran4 and pHuji are less sensitive to pH in cells than in vitro. Altogether, the strong pH sensitivity of pHuji and pHoran4 led us to further explore their utility as reporters of endocytosis and exocytosis.

Detection of single exocytic and endocytic events with TfR-red FPs

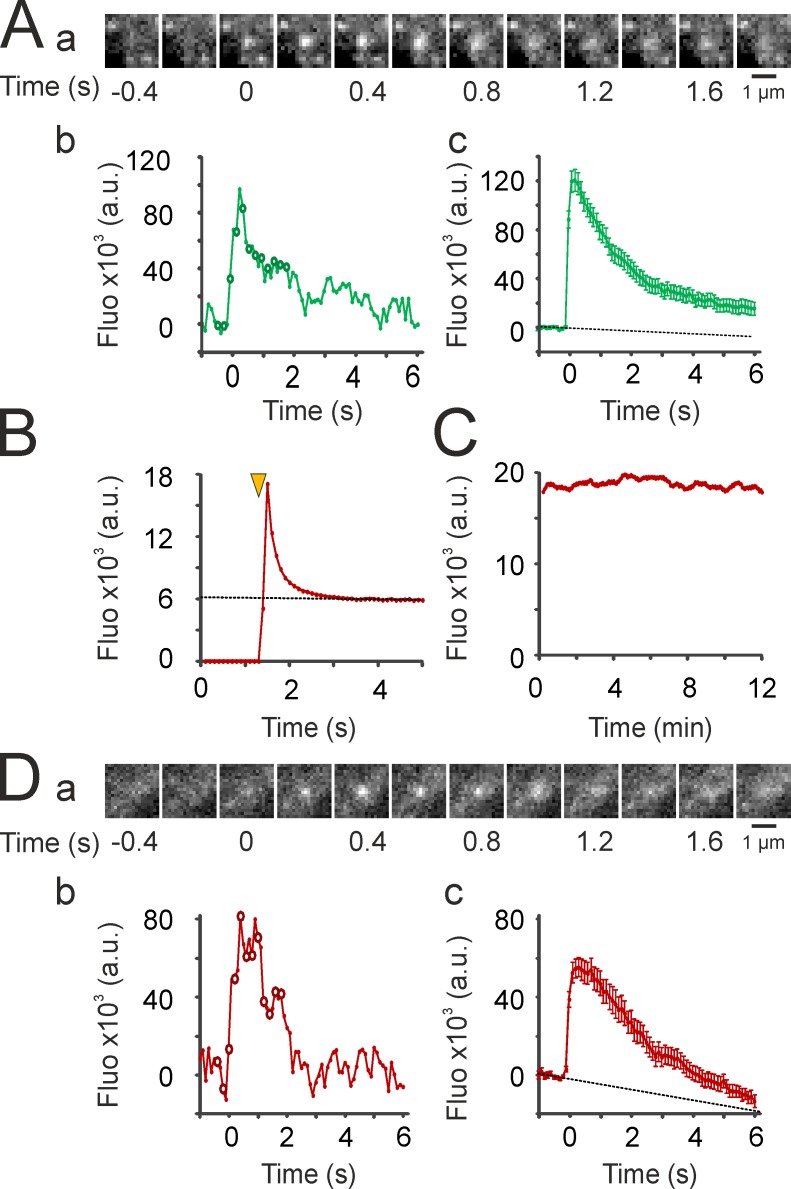

The TfR fused to SEP (TfR-SEP) has been widely used to detect single endocytosis (Merrifield et al., 2005) and exocytosis events (Xu et al., 2011; Jullié et al., 2014). Indeed, in cells transfected with TfR-SEP, exocytic events are readily detected in continuous TIRF recordings as sudden bursts of fluorescence as receptors go from an acidic intravesicular to the neutral extracellular compartment, and then rapidly diffuse from the site of exocytosis (Fig. 3 A). However, we noticed that pHuji, like earlier versions of its mApple template (Shaner et al., 2008), has a pronounced photoswitching behavior, with fluorescence going down to ∼35% of initial fluorescence in <2 s of continuous illumination in our recording conditions (Fig. 3 B). Nevertheless, this behavior did not impair the ability to obtain stable time-lapse recording conditions to study endocytosis (Fig. 3 C and see Fig. 7 D), and we could record exocytic events with similar profiles as those recorded with TfR-SEP (Fig. 3 D). Conversely, pHoran4 or pHTomato did not have a measureable photoswitching behavior and could also be used to detect exocytosis as shown previously (Li and Tsien, 2012; Jullié et al., 2014).

Figure 3.

Detection of exocytosis events with TfR-pHuji. (A) Detection of exocytosis events with TfR-SEP. (a) Example of an exocytosis event recorded at 10 Hz. (b) Quantification of the fluorescence of the event shown in panel a. A background image (average of five frames before the event) was subtracted before quantification. Circles correspond to images in panel a. (c) Mean of 56 events quantified as in panel b in three cells. Dotted line is an extrapolation of the linear fit of the nine data points before event detection to account for photobleaching. (B) Fluorescence of a representative cell (out of four recorded cells) expressing TfR-pHuji illuminated at the time marked by the yellow arrowhead and imaged continuously at 10 Hz. (C) Time-lapse recording of the same cell as in B (100-ms illumination, 0.25 Hz) similar to the ones used for imaging CCV formation. (D) Same as in A for exocytosis events detected in TfR-pHuji–expressing cells. (c) Mean fluorescence values for 40 events in three cells. Error bars represent SEM.

Figure 7.

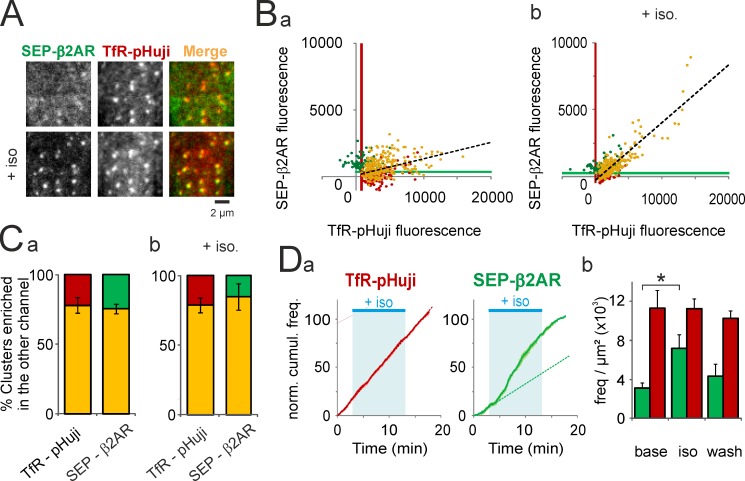

SEP-β2AR relocalizes and internalizes at TfR-pHuji clusters upon stimulation. (A) Portion of a HeLa cell cotransfected with SEP-β2AR and TfR-pHuji before (top) and during (bottom) application of the β2AR agonist isoproterenol (20 µM). (B) Fluorescence in the green and red channels of segmented clusters at pH 7.4 in a representative cell before (a) and during (b) application of isoproterenol. Yellow dots, clusters detected in both channels (238 [a] and 204 clusters [b]); green dots, clusters detected in the SEP channel only (77 [a] and 75 clusters [b]); red dots, clusters detected in the pHuji channel only (127 [a] and 96 clusters [b]). Black dashed lines show linear regressions of all TfR-pHuji clusters (R = 0.41 [a] and R = 0.87 [b]). Green and red lines show the lower limits of SEP and pHuji cluster detection, respectively. (C) Proportion for n = 7 cells of TfR-pHuji clusters enriched in SEP-β2AR (yellow) or not (red) according to the top-right quadrant defined by the SEP and pHuji lower detection limits determined as in B and vice-versa (yellow and green), before (a) and after (b) application of isoproterenol. (D, a) Frequency of events represented as cumulative number in seven cells of events detected with TfR-pHuji (left) and SEP-β2AR (right) during the course of the experiment, normalized at the end (17 min). Dotted lines are regression lines of the data before agonist application, extrapolated to the entire recording. (b) The frequency of scission events detected with SEP-β2AR (green) is significantly higher during isoproterenol application as compared with baseline (*, P < 0.01), whereas the frequency of TfR-pHuji–detected scission events (red) remains unchanged. Error bars represent SEM.

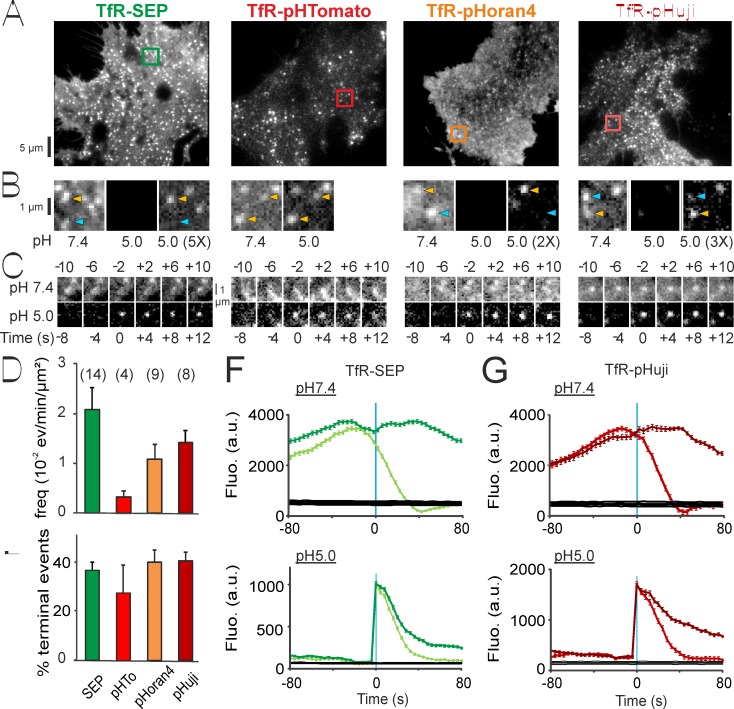

The ppH protocol (Merrifield et al., 2005) was developed to detect the formation of endocytic vesicles loaded with TfR-SEP. This protocol involves alternating the extracellular pH between 7.4 and 5.5 every 2 s. At pH 5.5, receptors fused to SEP on the plasma membrane are not fluorescent, and all observed fluorescence is attributable to receptors sequestered inside endocytic vesicles. Accordingly, the formation of a new endocytic vesicle is revealed when a cluster of receptors concentrated at a clathrin-coated pit (CCP) that is visible during a pH 7.4 interval remains visible during the following pH 5.5 interval. Importantly, optimal detection of these vesicles is achieved when the preexisting cluster is minimally fluorescent at pH 5.5, as is the case with SEP. Cells transfected with TfR-red FPs had a punctuate distribution over homogenous fluorescence similar to cells transfected with TfR-SEP (Fig. 4 A and Videos 1–4). The TfR clusters indeed correspond to CCPs (see Fig. 5, A–C). Some moving intracellular vesicles were seen in cells transfected with TfR-pHTomato (Video 1), reflecting the incomplete quenching of this FP in vesicles that are known to be acidic and usually not seen with SEP, pHoran4, or pHuji.

Figure 4.

Detection of endocytic vesicles containing TfR-red FPs. (A) Images of NIH-3T3 cells transfected with TfR fused to SEP, pHTomato, pHoran4, or pHuji at pH 7.4. (B) Details corresponding to the boxed areas in A, at pH 7.4 (left) and 2 s later at pH 5.0 (middle, same contrast; right, increased contrast as indicated). Note the complete quenching of some clusters (blue arrowheads), whereas others are still visible (yellow arrowheads) at pH 5.0. (C) Examples of events detected in cells transfected with the four FPs. (D) Mean frequency of scission events detected with the different markers. The number of cells tested is indicated. (E) Proportion of terminal scission events with the different markers. (F) Mean fluorescence of nonterminal (dark green, 984 events) and terminal (light green, 802 events) scission events at pH 7.4 (top) and 5.0 (bottom) aligned to their time of detection in 14 cells transfected with TfR-SEP. The black lines indicate 95% confidence intervals for significant enrichment. (G) Same as F for eight cells transfected with TfR-pHuji (dark red, 598 nonterminal events; light red, 447 terminal events). Error bars represent SEM.

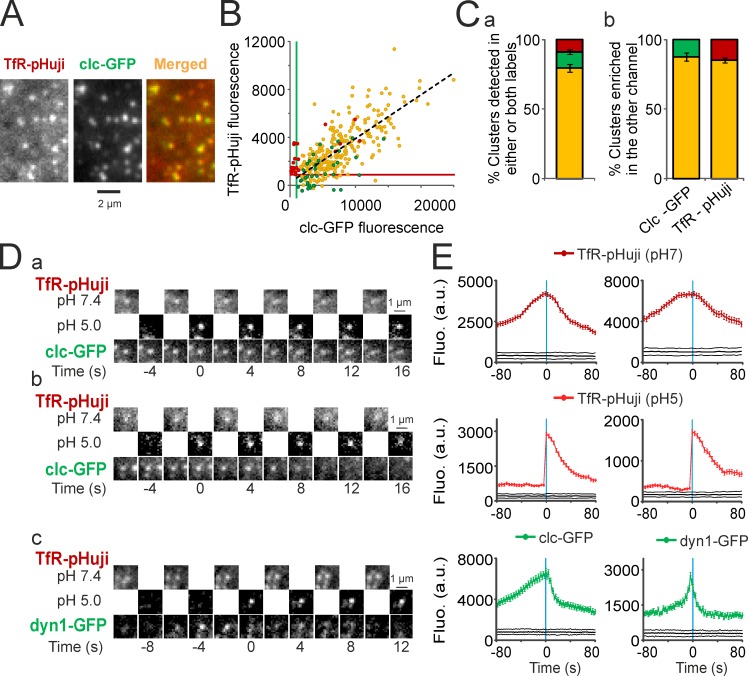

Figure 5.

TfR-pHuji colocalizes with CCPs and dynamin is recruited at the time of scission detected with TfR-pHuji. (A) Portion of a 3T3 cell cotransfected with TfR-pHuji and clc-GFP. The clusters of TfR-pHuji colocalize with CCPs (merged). (B) Fluorescence in the green and red channels of segmented clusters in a representative cell. Yellow dots, clusters detected in both channels (274 clusters); green dots, clusters detected in the GFP channel only (no matching structure in the red channel, 39 clusters); red dots, clusters detected in the pHuji channel only (no matching structure in the green channel, 34 clusters). Black dashed line shows linear regression of all clc-GFP clusters (R = 0.75). Green and red lines show the lower detection limits of GFP and pHuji clusters, respectively. (C, a) Proportion for n = 5 cells of clusters detected in both channels (yellow) or with either TfR-pHuji (red) or clc-GFP (green) as shown in B. (b) clc clusters enriched in TfR (yellow) or not (green) according to the top-right quadrant defined by the GFP and pHuji lower detection limits determined as in B and vice-versa (yellow and red). (D) Examples of nonterminal (a) and terminal (b) scission events in a cell coexpressing TfR-pHuji and clc-GFP. (c) Example of a scission event in a cell coexpressing TfR-pHuji and dyn1-GFP. Note the maximal recruitment of dyn1-GFP at −4 s. (E) Mean fluorescence of scission events aligned to their time of detection (left, 320 events in five cells cotransfected with TfR-pHuji and clc-GFP; right, 283 events in five cells cotransfected with TfR-pHuji and dyn1-GFP). Error bars represent SEM.

To visualize the formation of single CCVs using red FPs, we slightly modified the ppH protocol: we changed to low pH solution at pH 5.0 instead of 5.5 to maximize the quenching of plasma membrane receptors. TfR-SEP clusters were completely quenched during low pH intervals. TfR-pHoran4 and TfR-pHuji clusters were largely, although not completely, quenched, but TfR-pHTomato clusters were only partially quenched (Fig. 4 B). During the ppH protocol, scission events were clearly seen with all the constructs tested (Fig. 4 C). Similar to the original ppH protocol (Merrifield et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2011), low pH solution did not have any apparent adverse effect on cells, as the frequency of detected events was constant for at least 20 min of recording (see Fig. 7 D). We detected and quantified endocytic events using the algorithm developed previously (Taylor et al., 2011) with minor modifications (see Materials and methods for a complete description). The frequencies of events detected with TfR-pHoran4 and TfR-pHuji were only slightly lower than that obtained with TfR-SEP. In contrast, events detected in TfR-pHTomato–transfected cells were very rare (Fig. 4 D). In 3T3 cells, scission events fall into two categories: terminal events, where the cluster visible at pH 7.4 disappears <40 s after scission, and nonterminal events, where it remains visible (Merrifield et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2011). The proportion of terminal events measured in this dataset (∼40%) was very similar for SEP-, pHoran4-, and pHuji-tagged TfR (Fig. 4 E) and to published data (Taylor et al., 2011). Although there was some residual fluorescence at pH 5.0 before scission for the pHoran4 and pHuji constructs, the mean fluorescence time course of events detected with TfR-SEP, TfR-pHoran4, and TfR-pHuji were quite similar after scission (Fig. 4, F and G; and Fig. S3 A). Vesicles were also visible a little longer, presumably as they acidified (Fig. 4 G). This is consistent with the incomplete quenching of pHoran4 or pHuji fluorescence at acidic pH. We conclude from these results that pHuji and pHoran4 are both useful reporters of TfR trafficking and endocytic vesicles detection.

Dual color imaging of endocytosis with TfR-pHuji

An interesting application of a red pH-sensitive FP is to observe the recruitment profile of proteins involved in endocytosis. The ppH protocol has been extensively used for this purpose (Taylor et al., 2011). However, the need to use the green channel for the TfR-SEP signal made it necessary to work with mCherry or other red FP fusion constructs. Conversely, having a red reporter for endocytosis now makes it possible and convenient to use any of the many readily available and well-characterized GFP-tagged proteins in this same context. Because pHuji fluorescence emission occurs at a longer wavelength than that of pHoran4 (Table 1), spectral bleed-through from the green channel is minimized. It should thus be preferred for simultaneous two-color imaging with a green fluorescent probe. As a proof of concept, we have looked at the recruitment profiles of clathrin light chain A (clc-GFP) and dynamin 1 (dyn1-GFP) while assessing CCV formation with TfR-pHuji and the ppH protocol. As expected, clc-GFP is very well colocalized with TfR-pHuji (Fig. 5 A). Quantitative analysis shows that the fluorescence of clusters in both channels is well correlated (R = 0.71 ± 0.06, n = 5). The vast majority of clusters, identified by automated wavelet-based segmentation, were detected in both channels (Fig. 5 B, yellow dots, representing 79.4 ± 2.9% of all segmented clusters; and Fig. 5 C, a), consistent with previous results using TfR-SEP and clc-DsRed (Merrifield et al., 2005) or clc-mCherry (Taylor et al., 2011). Nevertheless, some clusters were detected in only one channel (Fig. 5 B, green and red dots) despite high fluorescence values in both channels. We thus set up objective thresholds for cluster enrichment by taking the fluorescence intensity of the dimmest detected cluster in the GFP or pHuji channel (Fig. 5 B, green and red lines, respectively) as our detection limit. Using these thresholds, 88.0 ± 2.0 or 84.9 ± 1.7% of clusters detected with clc-GFP or TfR-pHuji, respectively, contain both markers (Fig. 5 C, b). Moreover, clc-GFP was present at all times of CCV formation (Fig. 5, D and E), whereas dyn1-GFP is transiently recruited to sites of CCV formation reaching maximal intensity 4 s before vesicle detection at pH 5.0 (i.e., 2 s before vesicle scission; Fig. 5, D and E). The mean traces obtained with TfR-pHuji and clc-GFP or dyn1-GFP closely resemble the ones obtained with TfR-SEP and the corresponding mCherry fusion proteins (Taylor et al., 2011).

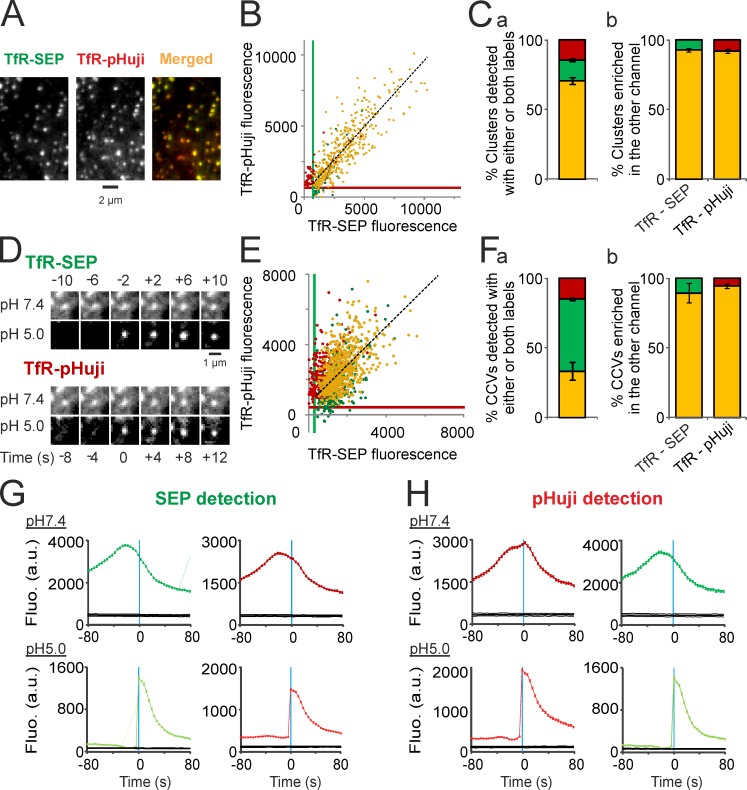

Simultaneous detection of CCV formation with TfR-SEP and TfR-pHuji

To test whether TfR-pHuji detects the formation of the same CCVs as TfR-SEP, we cotransfected 3T3 cells with both constructs and applied the ppH protocol. As expected, most clusters visible at pH 7.4 were colocalized (Fig. 6, A–C). Using the same quantitative analysis as before (see Fig. 5, A–C), we found that cluster fluorescence measured in both channels was strongly correlated (R = 0.83 ± 0.05, n = 5). Also, most clusters were detected in both channels (70.6 ± 2.4%), and 92.7 ± 1.4 or 92.0 ± 1.6% of those detected with SEP or pHuji, respectively, were enriched in both markers (Fig. 6 C). Therefore, TfRs are correctly targeted to CCPs regardless of their tag. Moreover, applying the ppH protocol yielded many endocytic events visible in both channels (Fig. 6 D), but also in only one or the other channel (Fig. S4, A and B). Similar results were obtained with cells cotransfected with TfR-SEP and TfR-pHoran4 (Fig. S3 B). Using a method of detection with increased sensitivity (see Materials and methods and Fig. S4 for details), we found that 33.2 ± 6.4% of events were detected in both channels, for a total of 5,126 events in five cells (Fig. 6 F, a). As for clusters visible at pH 7.4, CCV fluorescence measured with the two markers was positively correlated (R = 0.64 ± 0.03, n = 5; Fig. 5 E). Moreover, using objective thresholds determined as before, 89.3 ± 1.7 or 94.3 ± 1.7% of CCVs detected with SEP or pHuji, respectively, contained both markers (Fig. 6 F, b). Accordingly, the mean fluorescence of events detected either in the SEP (Fig. 6 G) or the pHuji (Fig. 6 H) channel was remarkably similar in both channels. We conclude from this data that the two FPs allow the detection of the same population of forming CCVs.

Figure 6.

Co-detection of TfR-SEP and TfR-pHuji within the same endocytic vesicle. (A) Portion of a 3T3 cell cotransfected with TfR-SEP and TfR-pHuji. (B) Fluorescence in the green and red channels of segmented clusters at pH 7.4 in a representative cell. Yellow dots, clusters detected in both channels (422 clusters); green dots, clusters detected in the SEP channel only (no matching structure in the red channel, 38 clusters); red dots, clusters detected in the pHuji channel only (no matching structure in the green channel, 89 clusters). Black dashed line shows linear regression of all TfR-SEP clusters (R = 0.85). Green and red lines show the lower detection limits of SEP and pHuji clusters, respectively. (C, a) Proportion for n = 5 cells of clusters detected in both channels (yellow) or with either TfR-pHuji (red) or TfR-SEP (green) as shown in B. (b) TfR-SEP clusters enriched in TfR-pHuji (yellow) or not (green) according to the top-right quadrant defined by the SEP and pHuji lower detection limits determined as in B and vice-versa (yellow and red). (D) Example of a scission event co-detected with TfR-SEP and TfR-pHuji. (E) Same analysis as in B performed on the fluorescence of CCVs at their time of detection at pH 5.0. Yellow dots, 303 CCVs; green dots, 570 CCVs; red dots, 119 CCVs. Black dashed line shows linear regression of all TfR-SEP–detected scission events (R = 0.59). Green and red lines show the lower detection limits of SEP and pHuji CCVs, respectively. (F) Same analysis as in C performed on detected CCVs at pH 5.0. SEP and pHuji lower detection limits were determined as in E. (G) Mean TfR-SEP and TfR-pHuji fluorescence at pH 7.4 (top) and 5.0 (bottom) of scission events detected in the green channel (3,721 events in five cells) aligned to the time of CCV detection. The black lines indicate 95% confidence intervals for significant enrichment. (H) Same as G with 2,177 scission events detected in the red channel. Error bars represent SEM.

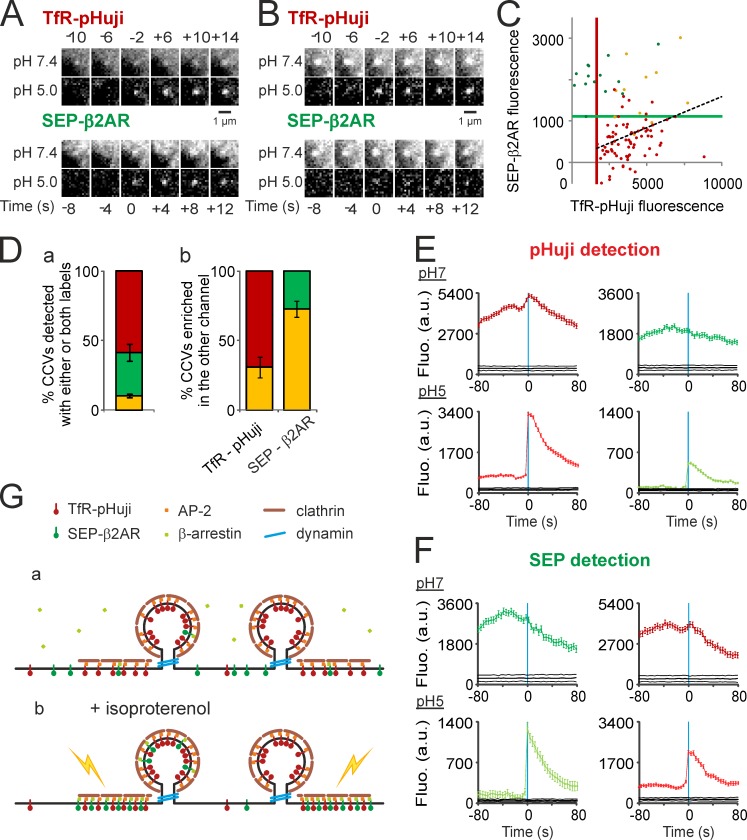

Differential sorting of TfR and β2AR into CCVs

Having demonstrated that SEP and pHuji could equally be used to detect the loading of individual CCVs with TfR, we next investigated their utility for detecting two distinct receptors into nascent CCVs. We cotransfected HeLa cells with TfR-pHuji and the β2AR tagged with SEP (SEP-β2AR), which is known to internalize through CCPs upon agonist binding (Goodman et al., 1996). Before stimulation, SEP-β2AR was mostly homogeneously distributed throughout the membrane (Fig. 7 A), although some dim concentrations of receptors could already be seen. Stimulation with isoproterenol (20 µM), a selective βAR agonist, quickly induced a dramatic relocalization of diffuse receptors into those clusters, leading to an overall 1.5 ± 0.2-fold increase of the mean cluster intensity (Fig. 7 B). Correlation analysis of cluster fluorescence showed that ∼80% of the clusters contained both receptors (Fig. 7 C), demonstrating that β2AR relocalizes to the vast majority of CCPs. This relocalization also translated in a significant increase in the correlation between the fluorescence intensities of both receptors before and after stimulation (R = 0.48 ± 0.08 and 0.82 ± 0.02, respectively; n = 5; P < 0.01; Fig. 7 B). The ppH protocol then revealed that the frequency of SEP-β2AR–containing vesicles increased 2.3-fold upon stimulation, whereas the frequency of TfR-pHuji–containing vesicles remained constant (Fig. 7 D).

A more detailed analysis of the data showed that some CCVs contained both receptors, whereas others contained no SEP-β2AR (Fig. 8, A and B). To determine the relative content of each receptor in single vesicles, we performed the same analysis as described above (Fig. 8, C and D). Contrary to the high correlation of clusters at pH 7.4 (Fig. 7 B) there was very little correlation between the intensities of both markers in a given CCV at pH 5.0 during stimulation (R = 0.32 ± 0.05, n = 7). This was significantly less correlated than the fluorescence intensity of CCVs colabeled with TfR-SEP and TfR-pHuji (Fig. 6 E, P < 0.05). Likewise, a minority of CCVs containing TfR-pHuji contained detectable SEP-β2AR (31.0 ± 7.4%, n = 7), in sharp contrast with the observation that 72.7 ± 5.9% of CCVs detected with SEP-β2AR also contained TfR-pHuji (Fig. 8 D). The segregation of SEP-β2AR in a subpopulation of TfR-pHuji vesicles is further reflected in the mean fluorescence traces: the amount of SEP-β2AR visible at pH 5.0 in CCVs detected with pHuji is less than half that of CCVs detected with SEP (38.8%; Fig. 8, E and F). In contrast, the mean fluorescence of TfR-pHuji at pH 5.0 varies less according to the channel of detection: the pHuji fluorescence in SEP-detected CCVs is 64.2% of that in pHuji-detected CCVs (Fig. 8, E and F). Finally, the results were reproducible when tags were exchanged in a converse experiment using pHuji-β2AR and TfR-SEP (Fig. S5), showing that the differential sorting of receptors to CCVs was not an artifact caused by the FPs. In conclusion, our data are consistent with a model in which β2ARs relocalize almost equally to all CCPs on the membrane, but are then differentially sorted inside nascent CCVs (Fig. 8 G).

Figure 8.

TfR-pHuji and SEP-β2AR are differentially sorted at the level of CCV formation. (A and B) Examples of a scission event visible with both TfR-pHuji and SEP-β2AR (A) or with TfR-pHuji only during isoproterenol application (B). Note the enrichment of β2AR at pH 7.4 but not in the CCV. (C) Fluorescence at the time of detection in the green and red channels of CCVs detected in a representative cell during isoproterenol application. Yellow dots, CCVs detected in both channels (11 CCVs); green dots, CCVs detected in the SEP channel only (14 CCVs); red dots, clusters detected in the pHuji channel only (76 CCVs). Black dashed line shows linear regression of all TfR-pHuji clusters (R = 0.33). Green and red lines show the lower limits of SEP and pHuji CCV detection, respectively. (D, a) Proportion for n = 7 cells of vesicles detected in both channels (yellow) or with either TfR-pHuji (red) or SEP-β2AR (green). (b) TfR-pHuji CCVs enriched in SEP-β2AR (yellow) or not (red) according to the top-right quadrant defined by the SEP and pHuji lower detection limits determined as in B and vice-versa (yellow and green). (E) Mean TfR-pHuji and SEP-β2AR fluorescence at pH 7.4 (top) and 5.0 (bottom) of scission events detected in the red channel (570 events in seven cells) aligned to the time of CCV detection. The black lines indicate 95% confidence intervals for significant enrichment. (F) Same as E with 324 scission events detected in the green channel. (G) Working model in which TfR (red lollipops) is constitutively clustered at all clathrin-coated structures (brown lines) via AP-2 binding (orange squares) and internalized in vesicles via the action of dynamin (blue rings) regardless of isoproterenol application. On the opposite, SEP-β2AR (green lollipops) in basal conditions is homogenously distributed at the cell surface (black line) and occasionally internalized (a), whereas during application of isoproterenol it is actively targeted to CCPs via recruitment of cytosolic β-arrestin (green squares; b). This relocalization of ligand-bound receptors to all CCPs leads to potential surface-localized intracellular signaling platforms (yellow bolts), whereas ligand-induced internalization of β2AR only occurs in a subpopulation of CCVs. Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

This work was motivated by our realization that the suboptimal performance of red fluorescent pH indicators largely stems from the fact that previous efforts had been mostly focused on optimizing pKa and had not given appropriate attention to maximizing nH. Indeed, our modeling of the response of pH indicators suggests that the value of the nH is actually more important than the value of the pKa to describe pH sensitivity. The majority of previous studies on FP-based pH sensors have assumed an apparent nH of 1.0 when fitting the pH titration curve, with two notable exceptions (Kneen et al., 1998; Sniegowski et al., 2005). Two intensity-based pH-sensitive red FPs, mNectarine (Johnson et al., 2009) and pHTomato (Li and Tsien, 2012), have suitably elevated pKas but relatively low nHs. SEP, the best available FP-based pH indicator, has a pKa that is close to optimal but is really set apart from other pH-sensitive FPs by its exceptionally high nH of 1.90. This high value is indicative of the existence of a second residue that can be deprotonated and interacts with the chromophore in a cooperative manner. Based on the observation that nH can greatly differ from protein to protein as a result of altered chromophore environment, we set out to engineer variants with larger fluorescence intensity changes to a given pH change.

To engineer a pH-sensitive red FP with a high nH, we used several strategies including direct mutation of the chromophore, modulation of the chromophore environment by site-directed mutagenesis of residues in close proximity, and random mutagenesis. Interestingly, the two most pH-sensitive red FPs identified in this work, pHuji and pHoran4, both have mutations at residue 163 (K163Y and M163K, respectively). This result indicates the importance of this position in regulating pKa and nH of red FPs. In the absence of an x-ray crystal structure, we cannot know for certain how these mutations are modulating the chromophore environment. However, the close proximity of the side chain of residue 163 to the chromophore phenolate group leads us to speculate that these mutations are serving to raise the pKa by either stabilizing the anionic form or destabilizing the protonated neutral form. Both tyrosine and lysine side chains normally have pKas in the range of 10 to 11, so deprotonation of the side chain of residue 163 in either pHuji or pHoran is unlikely to be acting cooperatively in the pH 5.0 to 7.5 range. Indeed, the observed increases in nH for both of these variants are relatively modest. However, they provide large improvements in their performance for imaging membrane trafficking events.

The properties of pHuji, with a pKa of 7.7 and an nH of 1.1, make it six- to sevenfold more pH sensitive than the previously described red pH sensor pHTomato (Li and Tsien, 2012) in the physiological range. However, pHuji should not be considered a replacement for SEP because it still falls short of SEP in terms of the magnitude of fluorescence fold change between pH 5.0 and 7.5, especially in situ. In addition, pHuji, like earlier versions of its mApple template (Shaner et al., 2008) and mApple-derived R-GECO1 (Wu et al., 2013), exhibits photoswitching behavior. This did not impair our detection sensitivity based on steady-state time-lapse (for endocytosis) or continuous (for exocytosis) recordings. Nevertheless, pHuji should be used with caution for quantitative imaging of exocytosis such as in synaptic terminals (Schweizer and Ryan, 2006) or protocols based on photobleaching (e.g., FRAP; González-González et al., 2012). Notably, pHoran4 does not display this behavior and should provide a good alternative to pHuji when needed. Clearly, the most appropriate application of pHuji is as the preferred second color for simultaneous dual color imaging of pH-sensitive processes with GFP- or SEP-based probes. Importantly, the emission peak of pHuji is well separated from that of GFP and there is almost no spectral shift associated with the transition from the low to high pH state. We demonstrate this possibility by imaging single endocytic events detected with TfR-pHuji together with GFP-tagged dyn1 and clc. The protein recruitment profiles revealed are similar to the converse experiment using mCherry-tagged proteins and TfR-SEP (Taylor et al., 2011). Therefore, two-color experiments with pHuji would be compatible with any of the high number of existing GFP fusion proteins and GFP-based sensors, such as ion sensors (Jayaraman et al., 2000; Dimitrov et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2011), Förster resonance energy transfer–based sensors (Ganesan et al., 2006), or experiments using blue-light photoactivatable molecules and proteins (Kramer et al., 2009; Tucker, 2012).

Finally, with two pH-sensitive tags at our disposal and the ppH assay, we can now address the differential sorting of two distinct receptors into individual endocytic vesicles. The question of early cargo sorting had already been addressed by previous studies at the level of the clustering at the plasma membrane (Puthenveedu and von Zastrow, 2006) or at the level of early endosomes (Lakadamyali et al., 2006). Here, we identify a new step at which receptor sorting can occur. By directly measuring the content of TfRs and β2ARs within a single vesicle at the time of its formation, we determined that selective cargo recruitment can occur at the time of internalization even though both receptors cluster equally well to CCPs after stimulation of the β2ARs. This result is unlikely to be an artifact of the imaging method because such segregation of receptors during vesicle formation did not occur when TfRs were labeled with SEP and pHuji. In contrast, we did observe the same behavior when the fluorescent tags were exchanged to label TfRs and β2ARs. This result is best explained if we consider that certain clathrin structures at the plasma membrane, sometimes referred to as plaques (Saffarian et al., 2009), can generate multiple CCVs, visible by light microscopy as so-called nonterminal events (Merrifield et al., 2005; Perrais and Merrifield, 2005; Taylor et al., 2011; this study), without collapsing. Such occurrences may correspond to clathrin-coated structures, best seen with freeze-etch electron microscopy (Fujimoto et al., 2000; Traub, 2009), consisting of large flat clathrin lattices concomitant with invaginations corresponding to nascent CCVs on their sides. In our model (Fig. 7 G), some receptors, such as TfR, and associated adaptor proteins would be equally well sorted to the two compartments, whereas others would be sorted preferentially to the flat parts, such as β2AR after agonist binding. Interestingly, many proteins associated with the plasma membrane show curvature-dependent binding (McMahon and Gallop, 2005). The curvature-sensing ability of β-arrestin, the likely adaptor protein for β2AR (Goodman et al., 1996; Traub, 2009), is currently unknown. However, other adaptor proteins such as epsin, an adaptor for ubiquitinated receptors, show strong preference for curved membranes (Capraro et al., 2010) and could affect the sorting of such receptors to the more deeply invaginated parts. A potential role for such differential targeting could be to ensure prolonged signaling from plasma membrane–localized platforms. Therefore, selective sorting within endocytic structures could be a general mechanism for the regulation of receptor signaling and trafficking.

In conclusion, we expect that pHuji will prove widely useful as the preferred second color of pH-sensitive probe for simultaneous imaging of multiple receptors and associated proteins during vesicle formation and release at the plasma membrane.

Materials and methods

Mutagenesis, library construction, and screening of pH-sensitive FPs

Directed evolution of pHorans and pHuji was performed by site-directed mutagenesis and multiple rounds of error-prone PCR using plasmids encoding mOrange and mApple as templates. All site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange lightning mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) and primers designed according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Error-prone PCR products were digested with XhoI and HindIII, ligated into pBAD/His B vector digested with the same two enzymes, and used to transform electrocompetent Escherichia coli strain DH10B (Invitrogen), which were then plated on agar plates containing LB medium supplemented with 0.4 mg/ml ampicillin and 0.02% wt/vol l-arabinose.

Single colonies were picked, inoculated into 4 ml of LB medium with 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin and 0.02% wt/vol l-arabinose, and then cultured overnight. Protein was extracted using B-PER bacterial extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. Screening for pH sensitivity of extracted protein was performed with a Safire2 fluorescence plate reader (Tecan) by measuring protein fluorescence intensity in buffers ranging from pH 4.0 to 9.0 by steps of 1.0. pKas and apparent nHs were estimated according to the screening results. Plasmids corresponding to the variants with relatively higher pKas and larger apparent nHs were purified with the GeneJET miniprep kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and then sequenced using the BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems).

Protein purification and in vitro characterization

To purify the pH-sensitive FPs, electrocompetent E. coli strain DH10B was transformed with the plasmid of interest using Micropulser electroporator (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Transformed bacteria were cultured overnight on agar plates containing LB and ampicillin. Single colonies were picked and grown overnight in 4 ml of LB supplemented with ampicillin at 37°C. For each colony, the 4-ml culture was then used to inoculate 250 ml of LB medium with ampicillin and grown to an optical density of 0.6. Protein expression was induced with addition of 0.02% arabinose and the culture was grown overnight at 37°C. Bacteria were harvested at 10,000 rpm, 4°C for 10 min, lysed using a cell disruptor (Constant Systems), and then clarified at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. The protein was purified from the supernatant by Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (ABT) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The buffer of the purified protein was exchanged with 10 mM Tris-Cl and 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.3, with Amicon ultra centrifugal filter (molecular weight cut-off of 10,000), for a final protein concentration of ∼10 µM. Molar ECs were measured by the alkali denaturation method (Gross et al., 2000). In brief, the protein was diluted into Tris buffer or 1 M NaOH and the absorbance spectra was recorded under both conditions. The EC was calculated assuming the denatured red FP chromophore has an EC of 44,000 M−1cm−1 at 452 nm. Fluorescence quantum yields were determined using mOrange (for pHOran4) or mApple (for pHuji) as standards.

Fluorescence intensity as a function of pH was determined by dispensing 2 µl of the protein solution into 50 µl of the desired pH buffer in triplicate into a 396-well clear-bottomed plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and measured in a Safire2 plate reader. pH buffer solutions from pH 3 to 11 were prepared according to the Carmody buffer system (Carmody, 1961). pKa and apparent nH were determined by fitting the normalized data to the following equation:

Cell culture and transfections

NIH-3T3 (European Collection of Cell Cultures) and HeLa (gift from A. Echard, Pasteur Institute, Paris, France) cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% Glutamax with (HeLa) or without (NIH-3T3) 1% penicillin/streptomycin and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured every 2–4 d for maintenance. 24 h before imaging, cells were transfected with 1–3 µg of total DNA, complexed with either 10 µl Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen; NIH-3T3) or 3–6 µl X-TREMEGene-HP (Roche; HeLa) in serum-free medium. 4 h later, cells were plated on 18-mm glass coverslips (coated with 0.1 mM polylysine for 3 min and then rinsed with 1× PBS for NIH-3T3) at a density of ∼70,000 cells/ml in supplemented DMEM.

TfR-SEP and dyn1-GFP plasmids were provided by C. Merrifield (Laboratoire d’Enzymologie et Biochimie Structurales, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) and clc-GFP was a gift of A. Echard (Pasteur Institute, Paris, France). pDisplay constructs of SEP, pHTomato, pHoran4, and pHuji were made by subcloning the genes of the pH-sensitive proteins into the pDisplay vector (Life Technologies) between the BglII and SalI restriction sites. The pDisplay vector is translated into a protein consisting of the N-terminal signal peptide and a C-terminal transmembrane domain of platelet-derived growth factor receptor, which enables anchoring of the fused protein to the cell surface. TfR-pHoran4, TfR-pHTomato, and TfR-pHuji were produced by PCR amplification of the relevant red FPs and inserted into the TfR-SEP vector using Nhe1 and Age1 sites.

Live cell fluorescence imaging

Live cell imaging was done at 37°C. Cells were perfused with Hepes buffered saline (HBS) solution with 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.4 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 20 mM Hepes, and 1 mM d-glucose, adjusted to pH 7.4 and 300–315 mOsmol/l and supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum for HeLa cells. For pH titration with pDisplay constructs, solutions were prepared as the HBS solution described using as pH buffers Hepes for solutions at pH 8.9, 8.0, 7.52, and 6.96, Pipes for solutions at pH 6.5 and 6.0, and MES for solutions at pH 5.5 and 5.09.

For the ppH protocol, a theta pipette (∼100-µm tip size achieved using a vertical Narishige puller; World Precision Instruments) was placed close to the recorded cell. One way contained HBS (pH 7.4; see previous paragraph for recipe) and the other contained a solution where Hepes was replaced with MES (MES buffered saline solution) and buffered at pH 5.0. Solution flow was alternated every 2 s using electrovalves (Lee Company) switching in synchrony with image acquisition. For experiments on β2AR internalization, isoproterenol (Tocris Bioscience) dissolved the day of the experiment was applied by exchanging both solutions in the application pipette with HBS solution and MES buffered saline solution containing 20 µM isoproterenol.

TIRF imaging was performed on an inverted microscope (IX71; Olympus) equipped with an Apochromat N oil 60× objective (NA 1.49), a 1.6× magnifying lens, and an electron multiplying charge coupled device camera (QuantEM:512SC; Roper Scientific). Samples were illuminated by a 473-nm laser (Cobolt) for SEP imaging, as well as by a coaligned 561-nm laser for red FP imaging. Emitted fluorescence was filtered using filters (Chroma Technology Corp.): 595/50 m for pHoran4 imaging, 620/60 m for pHuji and pHTomato imaging, and 525/50 m for SEP/GFP imaging. Simultaneous dual color imaging was achieved using a DualView beam splitter (Roper Scientific). To correct for x/y distortions between the two channels, images of fluorescently labeled beads (Tetraspeck, 0.2 µm; Invitrogen) were taken before each experiment and used to align the two channels (see Quantification of fluorescence intensities). The camera was controlled by MetaVue7.1 (Roper Scientific).

Semi-automated detection of endocytic events

The detection, tracking, quantification, and validation of endocytic events was performed using scripts in two ways. First, to analyze cells transfected with single label TfR (i.e., single transfections and cotransfections with clc-GFP or dyn1-GFP), we used the algorithm developed previously in Matlab 7.4 (Mathworks; Taylor et al., 2011) with minor modifications. This method of detection had been characterized as missing ∼30% of all events but has a low percentage of false positives (∼20%; Taylor et al., 2011), making it possible to work with large datasets. For these experiments, a quantitative detection of all endocytic events was not essential and we favored a fast and efficient data analysis. As shown in Fig. S10 of Taylor et al. (2011), the endocytic events not automatically detected are essentially similar to the detected ones. In brief, movies of cells acquired during the ppH protocol were divided in two or four parts: images of TfR-SEP (or, alternatively, TfR-red FP) at pH 5.0 and at pH 7.4, and, when applicable, images of the other color at pH 5.0 and at pH 7.4. Objects (i.e., TfR extracellular clusters, corresponding to CCPs in images at pH 7.4 and putative intracellular CCVs in images at pH 5.0) were detected and tracked using multidimensional image analysis (MIA; developed for Metamorph [Ropert Scientific] by J.B. Sibarita, Interdisciplinary Institute for Neuroscience, Bordeaux, France). Objects detected at pH 5.0 were considered bona fide endocytic events if (a) their intensity could be quantified correctly (regions of interet around the center of the object entirely defined within the images), (b) they overlapped with a cluster detected in images at pH 7.4 (minimum 20% overlap for TfR endocytosis and 10% for β2AR endocytosis), (c) their signal/noise ratio was greater than a given threshold (five for TfR endocytosis and three for β2AR endocytosis), (d) they could be tracked for more than three frames (i.e., more than 8 s), and (e) they either appeared de novo or saw their intensity increase at least threefold during the course of their tracking (criterion added as compared with Taylor et al. [2011] to compensate for partial quenching of extracellular clusters). The candidate events that passed these criteria were then visually inspected and validated as endocytic events by the user. There were 78 ± 3% of events validated by the user with TfR-SEP, a proportion very similar to previous work (Taylor et al., 2011). In contrast, 57 ± 4, 55 ± 4, and 24 ± 3% of candidate events detected in TfR-pHuji, TfR-pHoran4, and TfR-pHTomato were validated by the user, respectively. The increased number of false positives is most likely caused by increased noise as a result of incomplete quenching of the red FPs at pH 5.0.

Second, to detect endocytic events with two receptors, we found that only a small fraction of TfR-SEP and TfR-pHuji events was detected in both channels (∼20%; Fig. S4 E) using the method described in the previous paragraph. We noticed that only few events were indeed visible with one label only (Fig. S4, A and B). Most of them, however, should be considered as true endocytic events in both channels but were only detected as such by the original detection method in one (Fig. S4 C). The main reason for the occurrence of these false negatives was that the structure was not segmented properly by MIA (not detected or fused to a neighboring structure) because of the presence of background noise in pH 5.0 images, often coming from partial quenching of surface clusters (Fig. S4 C, pH 7.4 vs. pH 5.0 images). Therefore, we tried to improve the method to detect candidate endocytic events. To highlight sudden changes in fluorescence at pH 5.0 images, we computed a differential movie, i.e., each image minus an average of the five previous images plus a constant. Such highlighted objects were then detected using MIA as candidate events and tested for criteria (a–c) as described in the previous paragraph. Segmentation and tracking of these candidate events were performed by generating a background-subtracted movie consisting of images minus an average of five images before vesicle appearance (Fig. S4 C). After this step, the candidate event was kept if it could be tracked for more than three frames (criterion d). This second detection method was more sensitive than the first one (Fig. S4 D) but generated more false positives (30% for TfR-SEP, 50% for TfR-pHuji, 58% for β2AR-SEP, and up to 90% for β2AR-pHuji), which made the analysis a lot more time consuming. Therefore, we used it solely to analyze the coenrichment of receptors in CCVs. Once events were validated, event frequency was measured for each cell and normalized to the area of the cell visible on the TIRF image.

Quantification of fluorescence intensities

Fluorescence intensities plotted in Figs. 2 C and S2 (pDisplay experiments) are calculated as the mean intensity in a region of interest within the cell minus a mean background fluorescence taken from a region of interest outside the cell.

Exocytosis events (Fig. 3) were detected by eye and the fluorescence minus a background (i.e., average of five images before the event) was quantified in a 3-pixel (450-nm)-radius circle.

Fluorescence intensities in relation with scission events are calculated similar to Taylor et al. (2011). In brief, each value represents the mean intensity in a 2-pixel (300-nm)-radius circle to which the local background intensity is subtracted. This local background is estimated in an annulus (5 pixels outer radius and 2 pixels inner radius) centered on the region to be quantified, as the mean intensity of pixel values between the 20th and 80th percentiles (to exclude neighboring fluorescent objects). Quantification of fluorescence intensities in the other channel than the one used for detection was done using a set of x/y coordinates corrected for distortions caused by the Dual View system. This correction was calculated as a third order polynomial transformation using images of 0.2-µm TetraSpeck beads (Invitrogen) taken before each experiment. Bleed-through from one channel to the other was not corrected. Protein enrichment in clusters or vesicles was assessed by computing randomized datasets as in Taylor et al. (2011), reflecting the overall background fluorescence of the cell over which fluorescence enrichment becomes significant. Events could be classified as terminal or nonterminal depending on whether the fluorescence in pH 7.4 images 36 s after detection were <40% (terminal) or >60% (nonterminal) of the fluorescence in images at pH 7.4 just before detection.

We define objects (either pH 7.4 clusters or pH 5.0 scission events) as co-detected when they are independently detected in each channel <2 frames and 5 pixels (750 nm) apart. To determine the Euclidian distance between an object and its nearest neighbor in the other channel at a given frame, the x/y coordinates of one of the two datasets were corrected using the polynomial transformation described in the previous paragraph. Fluorescence intensity of each dot on the scatter plots of Figs. 5–8 and S5 is calculated as the intensity of an object (determined as described in the previous paragraph) at its time of detection. The lower detection limits of SEP and pHuji markers were estimated as the intensity of the least fluorescent detected object (Figs. 5–8 and S5, green and red lines). Any object falling below the red or green line is considered as containing only SEP or pHuji, respectively, and objects above both these lines as enriched in the other marker (i.e., containing both markers). Correlation between fluorescence intensities in the red and green channels is given as the Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient R.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows the in vitro pH sensitivity of proteins tested in this study and models of mutated residues in pHoran4 and pHuji relative to the chromophore. Fig. S2 illustrates the sensitivity of SEP, pHoran4, and pHuji in HeLa cells with collapsed pH gradients. Fig. S3 gives examples of scission events recorded in cells cotransfected with TfR-SEP and TfR-pHoran4. Fig. S4 describes the performance of the new algorithm for detecting scission events. Fig. S5 shows the detection of CCVs and differential sorting of TfR-SEP and pHuji-β2AR in the same cell. Table S1 shows the emission peak of FPs at different pH values. Table S2 gives the mutations of the pH-sensitive red FPs developed in this study. Videos 1–4 show recordings of the cells transfected with TfR-SEP, TfR-pHtomato, TfR-pHoran4, and TfR-pHuji, respectively, corresponding to Fig. 4 A, during the ppH protocol. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201404107/DC1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Natacha Retailleau for help with molecular biology and the University of Alberta Molecular Biology Services Unit and Christopher W. Cairo for technical support and access to instrumentation.

The work was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to R.E. Campbell; the Fondation Recherche Médicale, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (Interface program), and the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (CaPeBlE ANR-12-BSV5-005) to D. Perrais; an Alberta Ingenuity Scholarship to Y. Shen; and a pre-doctoral fellowship from the University of Bordeaux to M. Rosendale. R.E. Campbell holds a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Bioanalytical Chemistry.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- β2AR

- β2 adrenergic receptor

- CCP

- clathrin-coated pit

- CCV

- clathrin-coated vesicle

- clc

- clathrin light chain A

- dyn1

- dynamin 1

- EC

- extinction coefficient

- FP

- fluorescent protein

- HBS

- Hepes buffered saline

- MIA

- multidimensional image analysis

- nH

- Hill coefficient

- ppH

- pulsed pH protocol

- SEP

- superecliptic pHluorin

- TIRF

- total internal reflection fluorescence

- TfR

- transferrin receptor

- TYG

- threonine–tyrosine–glycine

References

- An S.J., Grabner C.P., and Zenisek D.. 2010. Real-time visualization of complexin during single exocytic events. Nat. Neurosci. 13:577–583 10.1038/nn.2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji J., and Ryan T.A.. 2007. Single-vesicle imaging reveals that synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis are coupled by a single stochastic mode. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:20576–20581 10.1073/pnas.0707574105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capraro B.R., Yoon Y., Cho W., and Baumgart T.. 2010. Curvature sensing by the epsin N-terminal homology domain measured on cylindrical lipid membrane tethers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132:1200–1201 10.1021/ja907936c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody W.R.1961. Easily prepared wide range of buffer series. J. Chem. Educ. 38:559–560 10.1021/ed038p559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov D., He Y., Mutoh H., Baker B.J., Cohen L., Akemann W., and Knöpfel T.. 2007. Engineering and characterization of an enhanced fluorescent protein voltage sensor. PLoS ONE. 2:e440 10.1371/journal.pone.0000440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto L.M., Roth R., Heuser J.E., and Schmid S.L.. 2000. Actin assembly plays a variable, but not obligatory role in receptor-mediated endocytosis in mammalian cells. Traffic. 1:161–171 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi S.P., and Stevens C.F.. 2003. Three modes of synaptic vesicular recycling revealed by single-vesicle imaging. Nature. 423:607–613 10.1038/nature01677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S., Ameer-Beg S.M., Ng T.T., Vojnovic B., and Wouters F.S.. 2006. A dark yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-based Resonance Energy-Accepting Chromoprotein (REACh) for Förster resonance energy transfer with GFP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:4089–4094 10.1073/pnas.0509922103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-González I.M., Jaskolski F., Goldberg Y., Ashby M.C., and Henley J.M.. 2012. Measuring membrane protein dynamics in neurons using fluorescence recovery after photobleach. Methods Enzymol. 504:127–146 10.1016/B978-0-12-391857-4.00006-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman O.B. Jr, Krupnick J.G., Santini F., Gurevich V.V., Penn R.B., Gagnon A.W., Keen J.H., and Benovic J.L.. 1996. β-Arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 383:447–450 10.1038/383447a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross L.A., Baird G.S., Hoffman R.C., Baldridge K.K., and Tsien R.Y.. 2000. The structure of the chromophore within DsRed, a red fluorescent protein from coral. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:11990–11995 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman S., Haggie P., Wachter R.M., Remington S.J., and Verkman A.S.. 2000. Mechanism and cellular applications of a green fluorescent protein-based halide sensor. J. Biol. Chem. 275:6047–6050 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D.E., Ai H.W., Wong P., Young J.D., Campbell R.E., and Casey J.R.. 2009. Red fluorescent protein pH biosensor to detect concentrative nucleoside transport. J. Biol. Chem. 284:20499–20511 10.1074/jbc.M109.019042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullié D., Choquet D., and Perrais D.. 2014. Recycling endosomes undergo rapid closure of a fusion pore on exocytosis in neuronal dendrites. J. Neurosci. 34:11106–11118 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0799-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneen M., Farinas J., Li Y., and Verkman A.S.. 1998. Green fluorescent protein as a noninvasive intracellular pH indicator. Biophys. J. 74:1591–1599 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77870-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R.H., Fortin D.L., and Trauner D.. 2009. New photochemical tools for controlling neuronal activity. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19:544–552 10.1016/j.conb.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakadamyali M., Rust M.J., and Zhuang X.. 2006. Ligands for clathrin-mediated endocytosis are differentially sorted into distinct populations of early endosomes. Cell. 124:997–1009 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., and Tsien R.W.. 2012. pHTomato, a red, genetically encoded indicator that enables multiplex interrogation of synaptic activity. Nat. Neurosci. 15:1047–1053 10.1038/nn.3126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon H.T., and Gallop J.L.. 2005. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature. 438:590–596 10.1038/nature04396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield C.J., Perrais D., and Zenisek D.. 2005. Coupling between clathrin-coated-pit invagination, cortactin recruitment, and membrane scission observed in live cells. Cell. 121:593–606 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesenböck G., De Angelis D.A., and Rothman J.E.. 1998. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 394:192–195 10.1038/28190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrais D., and Merrifield C.J.. 2005. Dynamics of endocytic vesicle creation. Dev. Cell. 9:581–592 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthenveedu M.A., and von Zastrow M.. 2006. Cargo regulates clathrin-coated pit dynamics. Cell. 127:113–124 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffarian S., Cocucci E., and Kirchhausen T.. 2009. Distinct dynamics of endocytic clathrin-coated pits and coated plaques. PLoS Biol. 7:e1000191 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaranarayanan S., De Angelis D., Rothman J.E., and Ryan T.A.. 2000. The use of pHluorins for optical measurements of presynaptic activity. Biophys. J. 79:2199–2208 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76468-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer F.E., and Ryan T.A.. 2006. The synaptic vesicle: cycle of exocytosis and endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16:298–304 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N.C., Campbell R.E., Steinbach P.A., Giepmans B.N., Palmer A.E., and Tsien R.Y.. 2004. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:1567–1572 10.1038/nbt1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner N.C., Lin M.Z., McKeown M.R., Steinbach P.A., Hazelwood K.L., Davidson M.W., and Tsien R.Y.. 2008. Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods. 5:545–551 10.1038/nmeth.1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu X., Shaner N.C., Yarbrough C.A., Tsien R.Y., and Remington S.J.. 2006. Novel chromophores and buried charges control color in mFruits. Biochemistry. 45:9639–9647 10.1021/bi060773l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniegowski J.A., Lappe J.W., Patel H.N., Huffman H.A., and Wachter R.M.. 2005. Base catalysis of chromophore formation in Arg96 and Glu222 variants of green fluorescent protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280:26248–26255 10.1074/jbc.M412327200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tantama M., Hung Y.P., and Yellen G.. 2011. Imaging intracellular pH in live cells with a genetically encoded red fluorescent protein sensor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133:10034–10037 10.1021/ja202902d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M.J., Perrais D., and Merrifield C.J.. 2011. A high precision survey of the molecular dynamics of mammalian clathrin-mediated endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 9:e1000604 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub L.M.2009. Tickets to ride: selecting cargo for clathrin-regulated internalization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:583–596 10.1038/nrm2751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi T., and Rutter G.A.. 2003. Multiple forms of “kiss-and-run” exocytosis revealed by evanescent wave microscopy. Curr. Biol. 13:563–567 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00176-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker C.L.2012. Manipulating cellular processes using optical control of protein–protein interactions. Prog. Brain Res. 196:95–117 10.1016/B978-0-444-59426-6.00006-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Liu L., Matsuda T., Zhao Y., Rebane A., Drobizhev M., Chang Y.F., Araki S., Arai Y., March K., et al. 2013. Improved orange and red Ca2+ indicators and photophysical considerations for optogenetic applications. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 4:963–972 10.1021/cn400012b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Rubin B.R., Orme C.M., Karpikov A., Yu C., Bogan J.S., and Toomre D.K.. 2011. Dual-mode of insulin action controls GLUT4 vesicle exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 193:643–653 10.1083/jcb.201008135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudowski G.A., Puthenveedu M.A., and von Zastrow M.. 2006. Distinct modes of regulated receptor insertion to the somatodendritic plasma membrane. Nat. Neurosci. 9:622–627 10.1038/nn1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Araki S., Wu J., Teramoto T., Chang Y.F., Nakano M., Abdelfattah A.S., Fujiwara M., Ishihara T., Nagai T., and Campbell R.E.. 2011. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science. 333:1888–1891 10.1126/science.1208592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.