Role for microbial production of phosphoantigen in infection-driven responses of primate γδ T cells in vivo.

Keywords: T cells, antigen, cell activation, memory response, lung

Abstract

Whereas infection or immunization of humans/primates with microbes coproducing HMBPP/IPP can remarkably activate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, in vivo studies have not been done to dissect HMBPP- and IPP-driven expansion, pulmonary trafficking, effector functions, and memory polarization of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. We define these phosphoantigen-host interplays by comparative immunizations of macaques with the HMBPP/IPP-coproducing Listeria ΔactA prfA* and HMBPP-deficient Listeria ΔactAΔgcpE prfA* mutant. The HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant shows lower ability to expand Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in vitro than the parental HMBPP-producing strain but displays comparably attenuated infectivity or immunogenicity. Respiratory immunization of macaques with the HMBPP-deficient mutant elicits lower pulmonary and systemic responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells compared with the HMBPP-producing vaccine strain. Interestingly, HMBPP-deficient mutant reimmunization or boosting elicits enhanced responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, but the magnitude is lower than that by HMBPP-producing listeria. HMBPP-deficient listeria differentiated fewer Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells capable of coproducing IFN-γ and TNF-α and inhibiting intracellular listeria than HMBPP-producing listeria. Furthermore, HMBPP deficiency in listerial immunization influences memory polarization of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Thus, both HMBPP and IPP production in listerial immunization or infection elicit systemic/pulmonary responses and differentiation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, but a role for HMBPP is more dominant. Findings may help devise immune intervention.

Introduction

Vγ2Vδ2 T cells exist only in humans and nonhuman primates and comprise 65–90% of total circulating human γδ T cells. Vγ2Vδ2 T cells can be activated by naturally occurring metabolites, often termed phosphoantigens, which include IPP from the mevalonate pathway and HMBPP from the MEP/1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate isoprenoid synthesis pathway [1, 2]. The MEP pathway in pathogens, such as Mtb, Mycobacterium bovis BCG, Lm, and malaria parasites [2, 3], is responsible for HMBPP and IPP production [3], whereas IPP can also be synthesized via the mevalonate pathway in MEP-negative pathogens [4] or host cells, particularly in infection or oncogenic transformation [5, 6]. Whereas HMBPP is much more potent than IPP for in vitro activation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [7–11], in vitro-activated Vγ2Vδ2 T cells can produce Th1 cytokines, IFN-γ and TNF-α; lyse infected cells or tumors through release of cytolytic effectors; and inhibit the intracellular growth of bacteria [1, 12–14]. Some of these in vitro findings have been replicated in vivo by administration of IL-2 plus HMBPP or equivalents [15–17]. In fact, phosphoantigen/IL-2 expansion and differentiation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells during early Mtb infection can increase host resistance to TB in primates [18]. Furthermore, molecular mechanisms, by which phosphoantigens interact with TCR, have been elucidated recently. It has been shown that Vγ2Vδ2 TCR recognizes HMBPP or IPP on the APC surface and that the binding and presentation of HMBPP are mediated by the novel molecule BTN3A1 [19–21].

Infections or immunization of humans and nonhuman primates with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing bacteria and parasites have been shown to induce in vivo activation and expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [12, 22]. Activated Vγ2Vδ2 T cells can traffic to and accumulate in the pulmonary compartment and intestinal mucosal interface [15, 23]. Following immune clearance of pathogens, some Vγ2Vδ2 T cells can express memory phenotypes similar to those seen in CD8+ αβ T cells [23, 24]. Consistent with these memory phenotypes, robust, accelerated, recall-like expansion and rapid production of antimicrobial cytokines can be seen after in vivo re-exposure to HMBPP/IPP-coproducing Mtb, BCG, or Lm [14, 23]. Rapid recall-like expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells after Mtb challenge of BCG-vaccinated macaques coincides with the vaccine-induced protection against a severe form of TB [23]. A recent study has shown that increased numbers of peritoneal Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in dialysis-related peritonitis are linked to HMBPP/IPP-coproducing bacteria and that overexpression of HMBPP synthase in bacteria enhances activation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [25].

However, in vivo studies have not been done to dissect HMBPP- and IPP-driven expansion, pulmonary trafficking, effector functions, and memory polarization of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells during infections with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing pathogens. In this context, it has yet to be determined whether infection or immunization with HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing bacteria can still induce sustainable adaptive-immune responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Simple administration of HMBPP or IPP does not appear to be conclusive for mimicking an in vivo setting, in which to address phosphoantigen-driven γδ T cell responses in infections [16, 26]. Comparative in vivo studies of host Vγ2Vδ2 T cell responses during infections or immunization are justified, as a number of HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing bacteria are still able to activate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [4, 25]. Addressing the above fundamental questions will enhance our understanding of immune biology of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in infections and help to design γδ T cell-targeted immune intervention or vaccine efforts. In the current study, we used our expertise of genetic manipulation of Lm and macaque models [14, 27, 28] to test the hypothesis that HMBPP/IPP-coproducing Listeria differ from HMBPP-deficient mutants in the ability to expand and differentiate or polarize Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Lm is the only pathogen known to possess the mevalonate and MEP pathways of isoprenoid biosynthesis, making it possible to knock out the MEP pathway without a loss of listeria viability for comparative studies [29]. We used homologous recombination to delete the gcpE gene encoding HMBPP synthase from our attenuated listeria strain and compared phenotypic and functional differences in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells stimulated by these listeria vaccine strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of the Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* (G155S for prfA*) mutant strain

Amplification of 5′ and 3′ flanking regions of GcpE was done using the following primer pairs: 5′-GATTTATTCTTTCTAGATTTGGCC-3′ and GCGAAATATTCTTTCATTCAAAGA-3′ and 5′-TCTTTGAATGAAAGAATATTTCGCCCGATTAAAGTAGCCGTGCTT-3′ and CTACTCCTGCAGCAATACCAA-3′. Resulting products were mixed in a 1:1 ratio, and PCR was performed using primers 5′-GATTTATTCTTTCTAGATTTGGCC-3′ and 5′-CTACTCCTGCAGCAATACCAA-3′ to generate one overlapping product lacking the GcpE coding region. PCR product was purified by gel extraction and digested with XbaI and PstI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Digested PCR product was ligated into plasmid pKSV7 and electroporated into Escherichia coli DH5α cells to generate gcpE-KO-pKSV7, which was transformed into electrocompetent Lm ΔactA prfA* (G155S) [27]. Plasmid-containing bacteria were selected for using BHI plates containing 5 μg/mL chloramphenicol. Selected colonies were grown in BHI media in the presence of chloramphenicol at 42°C for 24 h and then passaged repeatedly at 30°C in the absence of chloramphenicol. The loss of the gcpE coding region was confirmed by PCR analysis using primers 5′-TAGTCTACCATGGTGGTCTCTTTGAATGAAAG-3′ and 5′-TTTTCTGTCGACAACGATAATCCCCCTTG-3′.

Analysis of growth rate of the parental-attenuated Listeria and ΔgcpE mutant

Parental-attenuated Listeria ΔactA prfA* and ΔgcpE mutant as well as WT 10403S/ΔgcpE mutant strains were streaked on BHI plates containing 200 μg/mL streptomycin and incubated in a 30°C incubator for 18–24 h. Single colonies with same sizes were selected from each of listeria strains, incubated in 4 mL BHI broth, and allowed to grow to stationary phase overnight at 30°C. The cultures were diluted 1:100 in BHI broth and grown at 30°C, with aliquots of Listeria cultures removed every 2 h; OD was determined by spectrophotometer. There were no significant differences in growth between attenuated parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* and ΔgcpE mutant, as shown by comparable OD values over time in cultures (data not shown).

Isolation of PBMCs

PBMC isolation procedure was performed as described previously [15]. Briefly, freshly collected EDTA-anticoagulated blood was centrifuged, and the buffy coat was removed and diluted in PBS. Diluted buffy coats were layered over Ficoll-Paque Plus (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and centrifuged to separate PBMCs from RBCs and granulocytes. PBMCs were aspirated from the top layer of Ficoll-Paque, and contaminating RBCs were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA). Purified PBMCs were washed twice and counted using a hemacytometer.

In vitro stimulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in PBMC by Lm supernatants

The indicated mutant and parental Listeria strains were grown in BHI media at 30°C. When each of the strains reached an identical OD of 0.4, bacteria were harvested, washed, and then sonicated in 1 mL PBS. The same amounts of sonicated cells from each strain were filtered side by side through 4 kDa centrifugal filter units (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The bottom fraction was collected and stored in −80°C until use. PBMCs (100 μl), at a concentration of 5 × 106 PBMC/mL R10 media containing 500 U/mL IL-2, were placed in round-bottom, 96-well plates and stimulated with indicated dilutions of filtered Listeria lysates in the presence or absence of 1 μg/mL CD3 blocking antibody clone FN-18 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), which was shown to block TCR-driven proliferation. To degrade phosphoantigens in Listeria supernatants, supernatants were pretreated with 0.03 U/μl shrimp alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at 37°C, as described [25]. Cells were stimulated for 7 days before analysis. On Day 7, cells were stained with CD3-PE-Cy7 (SP34-2; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and Vγ2-FITC (7A5; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells washed with PBS and fixed in 2% formalin. Cells were analyzed using a CyAn flow cytometer. Lymphocytes were gated based on forward- and side-scatters and pulse-width, and at least 50,000 gated events were analyzed using Summit Data Acquisition and Analysis Software (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA).

i.v. Infection of Balb/c mice with Lm strains

CFUs (2×104) of indicated Lm strains were injected into the tail vein of 8-week-old Balb/c mice. Three days following infection, mice were killed; liver and spleen were weighed, harvested, homogenized; and serial dilutions of homogenate were placed on BHI plates to determine bacterial burden.

Rhesus macaques and vaccination/infection

Twelve Chinese-origin rhesus macaques were used in this study. All animals were maintained and used in accordance with guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were anesthetized with 10 mg/kg ketamine HCl (Fort Dodge Animal Health, Overland Park, KS, USA) for all blood sampling, infections, and treatments. Blood for white blood cell isolation was collected in EDTA tubes. Day 0 blood was drawn immediately before infection.

Respiratory immunization of rhesus macaques with attenuated Lm vaccine strains

CFU (108) of Listeria ΔactA prfA* or ΔgcpE mutant was administered through intratracheal inoculation to 12 Chinese-origin rhesus macaques (six/group). Macaques were sedated with Ketamine (10 mg/kg) and Xylazine (1–2 mg/kg) by i.m. injection. An endotracheal tube was inserted through the larynx into the trachea and placed at the carina, and a 1 mL solution containing the inoculum was administered through the endotracheal tube. A 5 mL air bolus was administered through the tube following the inoculum to ensure the entire solution was given. Seven weeks following initial infection, macaques were reinfected with 108 CFU of the same strain of Listeria through the intratracheal route.

BAL and BALF collection

BAL was performed as described previously [15]. Briefly, macaques were sedated with Ketamine and Xylazine. An intratracheal tube was inserted through the larynx into the trachea and placed at the carina. Saline solution was instilled and harvested from the lungs through the intratracheal tube. A maximum of 10 mg/kg solution was placed in the lungs of macaques, and the recovery rate was >50% in all cases.

Phenotyping of PBMC and BAL lymphocytes from macaques

For cell-surface staining and memory phenotype analysis of blood and BAL lymphocytes, PBMCs or isolated BAL cells were stained with up to six antibodies (conjugated to FITC, PE, allophycocyanin, Pacific Blue, PE-Cy7, and Alexa Fluor 700) for 15 min.

For T cell-subtype analysis, cells were stained with the anti-human Vδ2 primary antibody (15D; Thermo Scientific) for 15 min, washed, and then stained with a PE-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody for 30 min. Cells were washed and stained with surface antibodies; anti-human CD3 PE-Cy7 (SP34-2; BD Biosciences), anti-human Vγ2 FITC (7A5; Thermo Scientific), anti-human CD4-allophycocyanin (OKT4; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and CD8-Pacific Blue (RPA-T4; BioLegend) were added to the cells for 15 min. Cells were washed fixed with 2% formalin and analyzed on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

For T cell memory phenotype analysis, isolated cells were stained with anti-human CD3 PE-Cy7 (SP34-2; BD Biosciences), anti-human Vγ2 FITC (7A5; Thermo Scientific), anti-human CD4-Alexa Fluor 700 (OKT4; BioLegend), anti-human CD27-allophycocyanin (O323; BioLegend), anti-human CD28-Pacific Blue (CD28.2; BioLegend), and anti-human CD45RA-PE (5H9; BD Biosciences) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were washed, fixed in 2% formalin, and analyzed on an LSRFortessa flow cytometer.

Intracellular cytokine staining

PBMCs (0.5–1×106) plus mAb CD28 (1 μg/ml) and CD49d (1 μg/ml) were incubated in the presence or absence of 40 ng/mL HMBPP (provided by Dr. Hassan Jomaa, Giessen, Germany) in 200 μl final vol for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2, followed by an additional 5 h incubation in the presence of monensin (GolgiStop; BD Biosciences). After staining for cell-surface markers—CD3 PE-Cy7 (SP34-2; BD Biosciences), anti-human Vγ2 FITC (7A5; Thermo Scientific), and anti-human CD4-Alexa Fluor 700 (OKT4; BioLegend)—for 15 min, cells were permeabilized for 30 min (FOXP3 Fix/Perm Buffer; BioLegend) and stained for 45 min with cytoplasmic antibodies—anti-human IFN-γ-PE (4S.B3; BD Biosciences), anti-human TNF-α (MAb11; BD Biosciences), and anti-human IL-2-Pacific Blue (MQ1-17H2; BioLegend)—before fixation in formalin.

Inhibition of intracellular Listeria growth assay

This was done as we described previously [14]. For generation of infected target cells, 1 × 104 THP-1 cells or autologous monocytes were seeded into the bottom of 96-well plates and allowed to adhere for 2 h in a 37°C incubator (similar inhibition seen for Lm-infected THP-1 or autologous monocytes). Cells were infected with a multiplicity of infection of 100 of Lm Strain 10403S for 1 h, washed twice with PBS to remove extracellular bacteria, and media were replaced with R10 media containing 10 μg/mL gentamicin to kill all extracellular Lm.

To isolate effector cells, PBMCs, isolated from challenged macaques, were stained for Vγ2-FITC (7A5; Thermo Scientific) for 15 min and washed twice with PBS before sorting Vγ2+ T cells on a MoFlo (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Sorted cells were washed twice with RPMI medium 1640 (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine (MultiCell), and 20 mM HEPES (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), and aliquoted into wells containing target cells at the indicated ratios. The total volume of target cell:effector cell mixture was 200 μl in all cases. At indicated time-points following coculture, cells were centrifuged, media were removed, and cells were lysed using sterile water solution to release bacteria. Solutions were serially diluted and placed on BHI plates containing 200 μg/mL streptomycin to determine CFU counts of listeria.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using paired Student's t-test, unpaired Student's t-test, or Mann-Whitney U-test using Prism software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data compared were based on percentage, unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

A deletion of gcpE-encoding enzyme for producing HMBPP in the attenuated Listeria ΔactA prfA* reduced the listerial ability to expand Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in vitro

A number of bacterial and parasitic pathogens coproduce HMBPP/IPP in the MEP pathway, and infections of human and nonhuman primates with these MEP-carrying pathogens significantly expand Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [14, 23, 26]. However, it remains unknown whether HMBPP or IPP production in these microbial infections optimizes patterns or modes of Vγ2Vδ2 T cell responses to microbes. The understanding of this fundamental question would help to elucidate microbe-host interplay in disease pathogenesis, as well as to devise γδ T cell-targeted immunization or intervention. To this end, we sought to develop infectious HMBPP-deficient but IPP-producing mutant bacteria from HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental pathogens via deletion of the gcpE gene encoding the enzyme-producing HMBPP and to use mutant and parental strains as infection tools for comparative studies in macaques. Whereas most bacterial pathogens capable of expanding Vγ2Vδ2 T cells only carry the MEP pathway for HMBPP/IPP coproduction without coexistence of the mevalonate pathway for IPP production, a deletion of a key gcpE gene in the MEP pathway would shut down HMBPP/IPP coproduction (HMBPP metabolizes further to IPP; ref. [30]) and render these pathogens nonviable or nonreplicating [31, 32]. As Lm is the pathogen carrying MEP and mevalonate pathways for critical bacterial metabolism, we made use of our experience in genetic modification of attenuated Lm vaccine strain (Listeria ΔactA prfA*) for immunization of macaques [14, 27, 28]. We presumed that because the Listeria ΔactA prfA* vaccine strain already gets remarkably attenuated and reaches homeostasis after deletion of actA, additional deletion of gcpE from this attenuated strain would not further attenuate its infectivity/immunogenicity and thus, allowed us to conduct comparative, in-depth studies of Vγ2Vδ2 T cell responses in macaques [14].

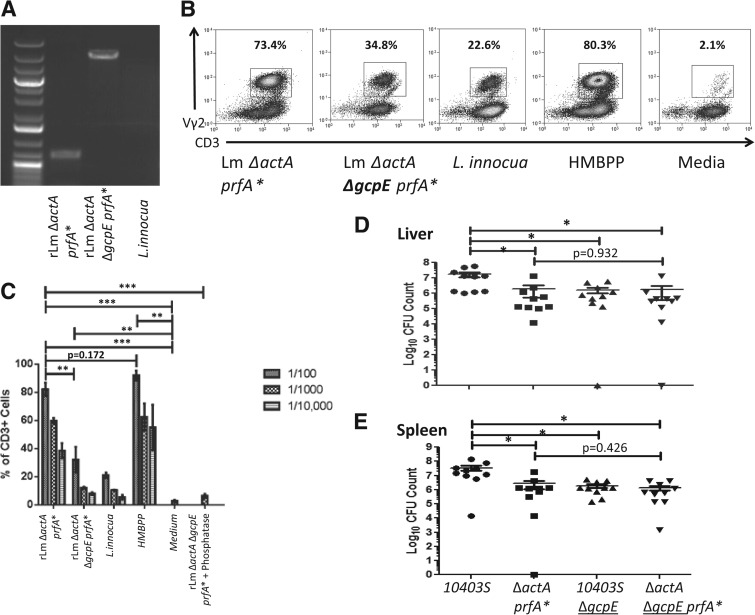

We used homologous recombination to remove the gcpE gene from our Listeria ΔactA prfA* vaccine strain. This approach allowed us to develop the gcpE-deleted Listeria ΔactA prfA* (ΔgcpE mutant) successfully (Fig. 1A). Whereas low molecular-weight lysate from HMBPP-producing parental listeria typically stimulated an expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in culture, lysates from HMBPP-deficient the ΔgcpE mutant or L. innocua without the gcpE locus induced significantly reduced expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 1B and C). Notable, alkaline phosphatase treatment of HMBPP-deficient listeria extract could abrogate expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 1C), suggesting that IPP, not other molecules, in HMBPP-deficient listeria extract mediated residual activation/expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. These results also suggest that the HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing ΔgcpE mutant was less efficient to expand Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in vitro than the HMBPP-producing parental vaccine strain.

Figure 1. Deletion of the gcpE gene encoding HMBPP synthase in the Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant vaccine reduced the listerial ability to expand Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in vitro but did not further attenuate listerial infectivity in mice compared with the parental strain.

(A) PCR products corresponding to the HMBPP-synthase gene gcpE fragments amplified from genomic DNA of indicated Lm strains. PCR products were generated using PCR primers described in Materials and Methods and run on a 0.8% agarose gel with GeneRuler 100 bp Plus DNA Ladder and confirmed by sequencing analysis. (B) Representative flow histograms for macaque PBMC cultures stimulated by different kinds of lysates derived from indicated Listeria strains with HMBPP and medium alone serving as controls. Percentage numbers denote expanded Vγ2+ T cells among CD3+ T cells in cultures stimulated at Day 7 by lysates in the presence of IL-2 (see details below). (C) Mean percentages of expanded γδ T cells following in vitro stimulation by different kinds of Listeria extracts in the presence (right) or absence of pretreatment of extracts by alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at 37°C. PBMCs were isolated from healthy, naive rhesus macaques, stimulated with sonicated extracts of Lm strains for 7 days in the presence of 500 U/mL human rIL-2, and then stained with CD3 and Vγ2 before flow cytometry analysis. Extract from Listeria innocua, known to lack gcpE, were used as a control. Medium alone and serial dilutions of HMBPP (40 ng/ml) also served as controls. Note that alkaline phosphatase pretreatment of extracts from the ΔgcpE mutant abrogated the mutant-induced expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Similar results were seen for the phosphatase treatment of extracts from the parental strain (data not shown; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001). (D and E) Bacterial burdens in livers (D) and spleens (E) of mice infected through i.v. inoculation with 2 × 104 CFU of the indicated Lm strains. Livers and spleens of mice were harvested 3 days postinfection (*P<0.05).

A deletion of gcpE-encoding enzyme for producing HMBPP did not further attenuate the attenuated parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* vaccine strain in mice

We then sought to determine whether removing gcpE from our attenuated Listeria strain would further impact bacterial replication and immunogenicity. This question needs to be addressed, as a study demonstrates that the HMBPP/MEP pathway influences virulence for a WT Listeria strain [31]. We confirmed that gcpE deletion in a WT strain of Listeria (10403S) resulted in decreases in bacterial loads in spleen and liver following i.v. challenge of mice (Fig. 1D and E, columns 1 and 3). In contrast, gcpE deletion from the attenuated Listeria ΔactA prfA* vaccine strain did not further attenuate or reduce infectivity, as infection of mice with this gcpE-deleted mutant did not cause a significant decrease in bacterial burdens (Fig. 1D and E, columns 2 and 4). These results demonstrated that the HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing ΔgcpE mutant resembled the parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* in aspects of replication and infection in mice. The attenuated Listeria ΔactA prfA* may have already adjusted homeostasis for replication after actA deletion, and that additional gcpE deletion would not further attenuate the listerial ability to infect and replicate in mice. We also cannot exclude the possibility that the prfA* transcription activator plays a role in the balance of listerial infection. Thus, data suggest that this gcpE deletion mutant is useful for comparative studies of whether HMBPP or IPP production during listeria immunization would elicit optimal in vivo responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in macaques.

Respiratory immunization of macaques with the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant elicited lower pulmonary responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells compared with HMBPP-producing parental listeria

To determine whether HMBPP production or IPP production during intracellular bacteria infection elicited optimal in vivo responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, rhesus macaques were vaccinated intratracheally with 108 CFU parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* and ΔgcpE mutant, respectively. We elected to perform intratracheal inoculation with Listeria, as we were interested in dissecting pulmonary and systemic immune responses of HMBPP- or IPP-driven Vγ2Vδ2 T cells after bacteria invasion to lungs. Previous studies have demonstrated that respiratory infections or immunization of macaques with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing bacteria, including Mtb and Yersinia pestis, can induce expansion or accumulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in lungs, which correlates with improved clinical outcomes after pulmonary infections [26]. As these organisms only have the MEP pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis, knockout of gcpE gene in the MEP pathway from these pathogens would eliminate HMBPP/IPP coproduction and thus, lead to a loss of the ability for these organisms to metabolize and survive [31]. The ability of the IPP-producing ΔgcpE mutant to survive and replicate in an absence of the MEP pathway gave us a unique opportunity to dissect HMBPP production versus IPP production for expansion and differentiation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells during infection or immunization with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing pathogens or vaccine vectors.

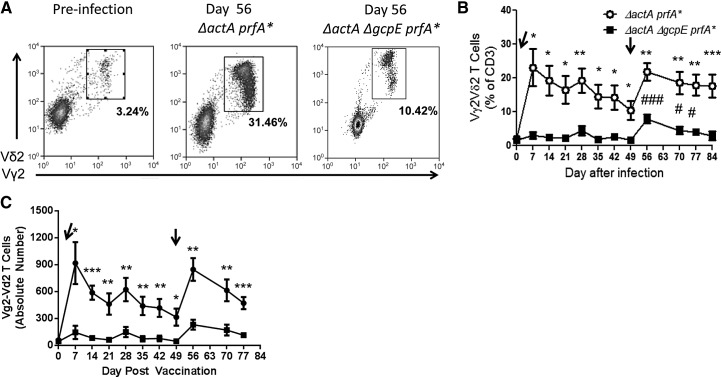

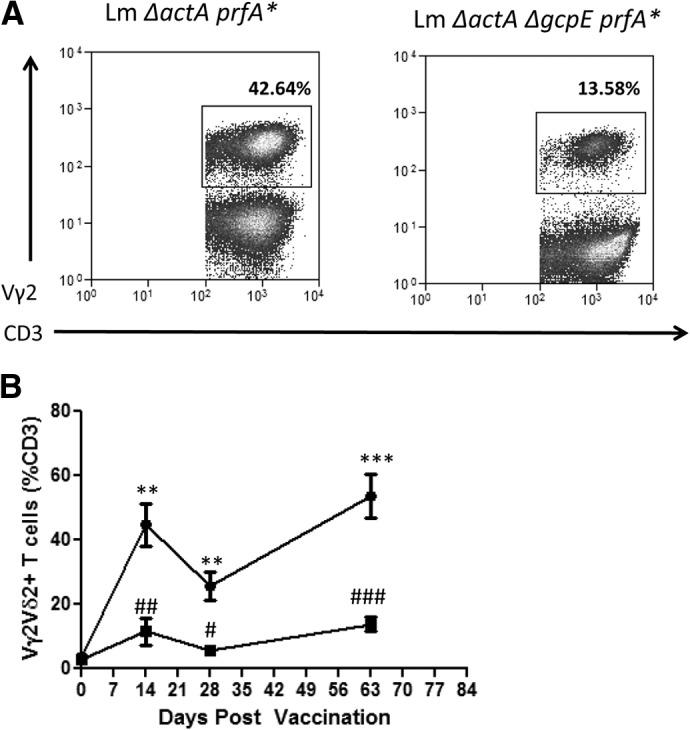

No clinical signs of disease or distress were seen in rhesus macaques vaccinated with Listeria ΔactA prfA* or Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant, and no Listeria bacteria were detected in culturing of BAL samples or blood collected at 7 days after infection (data not shown). As activated Vγ2Vδ2 T cells during infection of macaques with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing Listeria and Mtb can readily traffic to and accumulate in the pulmonary compartment [14, 23], we asked a question as to whether HMBPP is a major microbial factor driving such pulmonary responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. To address this, we determined in vivo dynamics of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in the airway through assessing their changes in BALF after infection. Respiratory immunization of macaques with the HMBPP-deficient mutant led to a significant reduction in numbers of these γδ T cells in the airway compared with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental listeria (Fig. 2A and B), suggesting that HMBPP plays a dominant role in eliciting pulmonary responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Nevertheless, the HMBPP-deficient mutant was still able to elicit significant increases in percentages of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in the airway compared with baseline levels (Fig. 2B). In fact, secondary immunization of macaques with the parental HMBPP/IPP-coproducing strain or the HMBPP-deficient mutant elicited enhanced increases in pulmonary Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. These results support the view that although HMBPP plays a dominant role in eliciting pulmonary Vγ2Vδ2 T cells during respiratory listeria immunization, HMBPP production and IPP production by listeria contribute to increases in Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in the pulmonary compartment.

Figure 2. Immunization of macaques with the HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant elicited lower pulmonary responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells compared with the HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental strain.

(A) Representative flow histograms of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in BAL cells from two macaque at Day 63 after respiratory exposure to Listeria ΔactA prfA* (left) and Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant, respectively. Day 63 was 14 days after the secondary exposure. (B) Mean percentage numbers of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in BAL cells at various time-points following listeria exposure. Asterisks indicate statistically significant comparisons of time-points between the group of macaques exposed to the Listeria ΔactA prfA* and the group exposed to the Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant (**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001). Number signs indicate statistically significant comparisons between the indicated time-point and Day 0 for the group of macaques exposed to Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant (#P < 0.05; ##P < 0.01; ###P < 0.001).

Immunization with the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant elicited systemic recall-like responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, but the magnitude was lower than that induced by the parental vaccine strain

We next sought to determine whether HMBPP in intracellular bacterial infection or immunization is also crucial for eliciting systemic expansion and recall-like expansion of circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Respiratory immunization of macaques with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* significantly expanded blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells at postimmunization time-points (Fig. 3A–C). Indeed, circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in macaques vaccinated with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing listeria were increased in means from baseline <3% up to 24% of all circulating T cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, primary immunization with the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant induced low-level increases in circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 3A–C), suggesting that HMBPP in listeria is responsible for systemic responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells following primary listeria immunization of macaques.

Figure 3. Immunization with the HMBPP-deficient IPP-producing Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant elicited recall-like systemic responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, but the magnitude was lower than that induced by the parental strain.

(A) Representative flow histograms of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in PBMCs from a macaque before (preinfection; left) and at Day 56 after (middle) pulmonary exposure to HMBPP/IPP-coproducing Listeria ΔactA prfA* and a macaque exposed at Day 56 to the Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant (right). Day 56 was 7 days after secondary exposure. Flow panels are gated on CD3+ lymphocytes. (B and C) Mean percentages of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in blood of rhesus macaques (B) or mean absolute numbers of them (C) at various time-points after Listeria exposures (arrows). Macaque group shown in open symbols were challenged with parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* strain; those shown in solid symbols were vaccinated with the ΔgcpE mutant. Asterisks indicate statistically significant comparisons of time-points between the two group of macaques (*P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001); number signs indicate statistically significant comparisons between the indicated time-point and Day 0 or 49 for the group of macaques exposed to the Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant (#P < 0.05; ###P < 0.001).

Interestingly, whereas second immunization with the HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental strain induced a rebound expansion of circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 3A–C), enhanced expansion of blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells was seen at 1–3 weeks after secondary immunization with HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant (Fig. 3A–C). Such enhanced expansion was statistically significant, although the magnitude was lower than that seen in macaques revaccinated with the parental strain (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that IPP production during secondary immunization by the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant is still able to elicit detectable, enhanced expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in pulmonary and circulating compartments, whereas HMBPP/IPP coproduction in listerial immunization dominantly drives systemic expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.

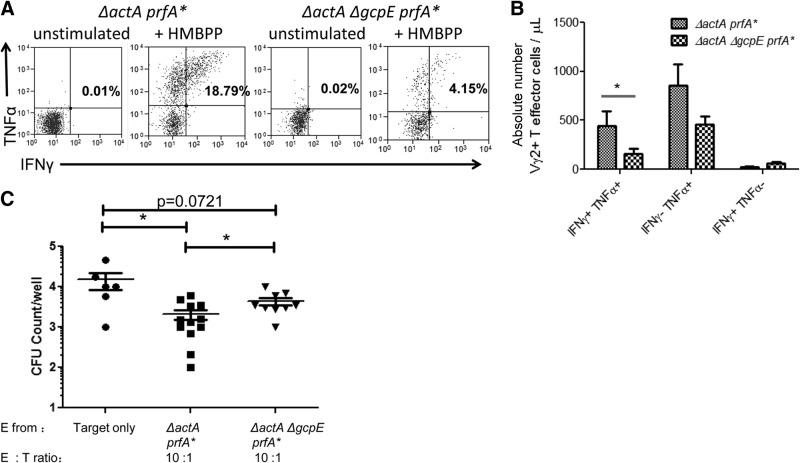

The HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant differentiated fewer Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells capable of coproducing IFN-γ and TNF-α and inhibiting intracellular listeria compared with the parental strain

We next sought to determine whether immunization with the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant was less efficient to differentiate effector functions of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells than the parental HMBPP/IPP-coproducing strain. To this end, we took advantage of our previous observation that Vγ2Vδ2 T cells after listerial immunization of macaques could differentiate to effector cells producing IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to in vitro HMBPP stimulation and that Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells can inhibit intracellular listerial growth [14]. Immunization of macaques with the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant elicited significantly smaller numbers of Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells capable of coproducing IFN-γ and TNF-α than those infected with the parental strain (Fig. 4A and B), suggesting that HMBPP in listerial immunization dominantly differentiates Vγ2Vδ2 T cells into antimicrobial effector cells coproducing IFN-γ and TNF-α cytokines.

Figure 4. HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing listerial immunization differentiated fewer Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells capable of coproducing IFN-γ/TNF-α and inhibiting intracellular listeria than HMBPP/IPP-coproducing listerial infection.

(A) Representative flow histograms showing Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells producing/coproducing IFN-γ and TNF-α at 63 days following primary Listeria exposure. PBMCs were stimulated with anti-CD28 and anti-CD49d antibodies in the absence (unstimulated) or presence of HMBPP (+HMBPP). Panels were gated on Vγ2+CD3+ lymphocytes. Numbers in upper-right quadrant indicate the percentages of Vγ2+ effector cells. (B) Graph data showing absolute numbers of phosphoantigen-specific IFN-γ+ TNF-α+ Vγ2+ T cells (double-positives), TNF-α+ Vγ2+ T cells, or IFN-γ+ Vγ2+ T cells in blood (μl). Absolute numbers were calculated by first subtracting cytokine+ Vγ2+CD3+ T cell percentage from the unstimulated panel from cytokine+ Vγ2+CD3+ T cell percentage in the HMBPP-stimulated panel and then multiplying by total CD3+ T cells derived from complete blood counts. (C) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from macaques infected with the HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant showed a reduced capability to inhibit intracellular listerial growth. Shown are CFU counts of listeria harvested from infected autologous macrophages following 4 h coculture with Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. PBMCs isolated from blood of macaques on Day 84 after primary listerial immunization were used to purify Vγ2Vδ2 T cells through FACS sorting. Purified Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from macaques exposed to the indicated listerial strains were cocultured with 104 autologous macrophages at the indicated ratios in 200 μl R10 media containing gentamicin to inhibit extracellular listerial growth. Following coculture, cells were lysed with 200 μl sterile water to release listeria. Lysates were serially diluted and plated on BHI plates containing streptomycin for 18–24 h before counting, and CFU counts for each well were determined. One to three wells of coculture were set up and analyzed from each of six macaques/group, depending on the availability of isolated macrophages or Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Data were expressed by log scale representing total CFU/well, with a mean value (horizontal lines) for each group of macaques (*P < 0.05).

To determine if HMBPP in listerial infection differentiated more Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells exerting antilisteria function, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells isolated from macaques at Day 84 after primary listerial immunization were cocultured with listeria-infected autologous macrophages. After 4 h cocultures, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from macaques vaccinated with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental listeria could significantly inhibit the intracellular growth of listeria at a E:T cell ratio of 10:1 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, Vγ2Vδ2 T cells from macaques vaccinated with the HMBPP-deficient Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant exhibited a significantly reduced ability to inhibit intracellular listeria (Fig. 4C).

These data therefore suggested that the HMBPP-deficient listerial mutant immunization differentiated fewer Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells capable of coproducing IFN-γ and TNF-α and inhibiting intracellular listeria than HMBPP/IPP-coproducing listerial infection.

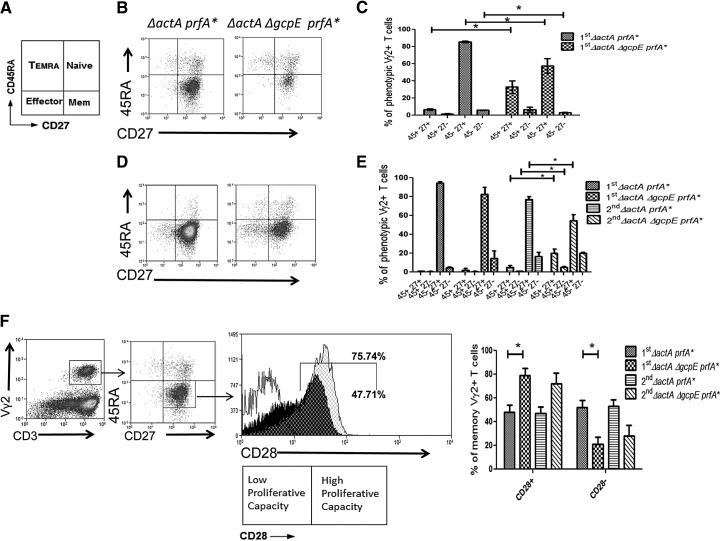

HMBPP deficiency in Listeria immunization influenced polarization of the memory phenotype of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells

Finally, we sought to determine whether HMBPP production or IPP production in respiratory listerial immunization impacted the optimal development of the memory phenotype of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Primary or secondary immunization of macaques with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* led to increased percentages of blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells displaying a CD27+CD45RA− memory-like phenotype in the circulating compartment (Fig. 5A and C). In contrast, immunization with the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant induced significantly lower percentages of circulating memory-like Vγ2Vδ2 T cells and higher percentages of circulating, naive-like (CD27+CD45RA+) cells than the parental strain (Fig. 5C). In the airway, similar percentages of memory-like Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were seen after primary immunization with either listeria strain (Fig. 5D and E). However, reimmunization with the HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental strain led to higher percentages of memory-like Vγ2Vδ2 T cells and lower percentages of naive-like Vγ2Vδ2 cells in the airway than HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant reimmunization (Fig. 5D and E, P<0.05 for both comparisons after reinfection).

Figure 5. HMBPP-synthase deficiency in Listeria influenced polarization of the memory phenotype of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells following listerial exposure.

(A) Diagram of phenotypic subsets of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells based on CD27 and CD45RA expression. (B and D) Representative flow histograms of Vγ2Vδ2 T cell subtypes based on CD27 and CD45RA expression in blood (B) and BAL cells (D). Flow histograms are gated on Vγ2+CD3+ lymphocytes. (C and E) Graphs of phenotypic subsets of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in blood (C) and BAL cells (E) following primary (1st) or secondary (2nd) infection of macaques with the indicated listerial strains. Similar data were seen for blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells after second infection (data not shown). Note that there are greater numbers of memory-type (CD45RA−CD27+) Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in macaques infected with the HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental strain than in those infected with the HMBPP-deficient, IPP-producing mutant (*P<0.05). (F) Gating strategy for determining CD45RA−CD27+CD28− and CD45RA−CD27+CD28+ subsets (two-dimensional flow histograms on left) of Vγ2Vδ2 T memory cells and representative one-dimensional flow histograms (middle panel) of CD28+ Vγ2Vδ2 T memory cells in BAL of a macaque infected with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental Listeria ΔactA prfA* (black histogram) or a macaque infected with the HMBPP-deficient Listeria ΔactA ΔgcpE prfA* mutant (gray histogram). Isotype control for CD28 expression is shown as a white histogram. Shown on right are mean percentages of CD28+ and CD28− Vγ2Vδ2 T-memory subsets in BAL of macaques following first or second infection with indicated listerial strains. Data of the first infection were generated from blood collected at Day 42, and those of the second infection were derived from blood collected at Day 84. A significant difference between the groups was seen on Day 42 (*P<0.05), and a similar trend was noted on Day 84, despite no statistical significance.

It has recently been shown that human memory Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, analog to CD8+ T cells, could mount antigen-driven proliferative responses in association with CD28 expression and stimulation [10, 33] and that “early or central memory” Vγ2Vδ2 T cells express CD28, whereas “late memory” Vγ2Vδ2 T cells lose CD28 expression [10]. We therefore compared CD28 expression on memory-like Vγ2Vδ2 T cells between macaque groups infected with the HMBPP-deficient listeria mutant and the HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental strain. Interestingly, phenotypic analysis of memory-like Vγ2Vδ2 T cells demonstrated that macaques exposed to HMBPP/IPP-coproducing parental listeria shifted toward the development of the CD28− late memory pool in the pulmonary compartment, whereas primary and secondary exposure of macaques to the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant induced a higher percentage of CD28+ “early memory” Vγ2Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 5F). Thus, these results suggest that HMBPP/IPP coproduction in listerial immunization more vigorously stimulates and skews Vγ2Vδ2 T cells toward the late memory phenotype, whereas IPP production favors early/central memory development.

DISCUSSION

Our study represents the first in vivo comparative investigation dissecting importance of HMBPP/IPP coproduction versus IPP production for eliciting Vγ2Vδ2 T cell expansion, differentiation, and memory formation during intracellular bacterial immunization. A number of pathogens, including most detrimental ones that cause TB, cholera, diphtheria, and plague, indeed carry the MEP pathway for HMBPP/IPP coproduction without an additional mevalonate IPP pathway [3, 31] and activate/expand Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Our primate model and listerial mutant system provide a unique opportunity to document whether and how HMBPP deficiency during immunization with HMBPP-producing bacteria impacts in vivo responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. The current in vivo work extends a previous human study [25] by providing new information regarding longitudinal perspectives of expansion magnitude, pulmonary versus systemic responses, effector function, and memory phenotypes of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells during infection with HMBPP-producing or HMBPP-deficient listeria. The greater expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells by HMBPP-producing listerial immunization may be explained by the recent finding that the HMBPP/BTN3A1 complex appears to exhibit higher affinity and a longer half-life than the IPP/BTN3A1 [19]. Furthermore, the current study also allows us to make the first observation conceiving the ability of IPP production to elicit enhanced systemic and pulmonary responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells in intracellular bacterial immunization.

Macaques immunized with HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant and its parental strain serve as a useful model system for proof-of-concept studies, as these two paired listeria vaccine strains share similar in vivo infectivity, without further attenuation after gcpE deletion. Comparative studies using mutants derived from WT listeria, Mtb, or other bacteria cannot be done, as gcpE deletion leads to significant attenuation for them. It is worth mentioning that our in vivo experiments are focused on HMBPP- or IPP-driven Vγ2Vδ2 T cell responses in pulmonary and systemic compartments, instead of disease virulence or pathogenesis during infection. The ΔgcpE mutant does not further attenuate Listeria replication and infectivity in vivo, despite a loss of the ability to produce HMBPP, and therefore, provides a reasonable setting in which to compare the parental HMBPP-producing Listeria ΔactA prfA* for studies of HMBPP- and IPP-driven immune responses and effector functions of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. The results from our model system are complementary to those from the human study using overexpression of gcpE gene [25].

The respiratory immunization with the parental and mutant listeria in the current study mimics a natural pulmonary infection with HMBPP/IPP-coproducing pathogens to prove the concept that HMBPP and/or IPP in immunization or infection elicit pulmonary/systemic responses and effector function of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Our results clearly suggest that HMBPP in immunization or infection is a dominant microbial factor responsible for pulmonary/systemic responses and differentiation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells and help to explain the earlier finding that BCG or Mtb infection induces remarkable expansion—pulmonary trafficking/accumulation of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [14, 23, 26]. The in vivo data are supportive of the role of HMBPP in activating human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, as reported in the study at cross-sectional time-points of dialysis-induced peritoneal infections [25]. Our data, although complementary/confirmative, provide comprehensive in vivo details of remarkable expansion, trafficking, effector function, and “early/late memory” phenotype of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells during immunizations or infections. The findings also argue against the presumption that other speculative microbial antigens [34], cytokines alone [26], or other host factors [35, 36] during infections might also play a major role in the in vivo activation/expansion of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.

Notably, IPP production in listerial immunization can also elicit notable systemic and pulmonary responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells. To a less extent, listerial IPP appears to resemble HMBPP in the ability to activate/expand pulmonary and circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Interestingly, detectable, enhanced increases in circulating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells were seen following secondary pulmonary infection with the HMBPP-deficient ΔgcpE mutant, suggesting that IPP-primed Vγ2Vδ2 T cells could undergo enhanced expansion after the secondary IPP exposure. It is likely that IPP-activated Vγ2Vδ2 T cells can also undergo clonal expansion in peripheral lymphoid tissues, including tracheal/nasal-associated lymphoid tissue, and circulate in the blood and airway. Given that the infection with the HMBPP-deficient listeria mutant vaccine is transient and nonpathogenic, in vivo immune responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells may be driven primarily by listerial IPP, instead of stressed host cells. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that infection-mediated IPP production by host cells contributes to activating Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. Orthopoxvirus, incapable of producing HMBPP, appears to prime and activate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, perhaps through “cellular stress” production of IPP by infected cells [37, 38]. Some in vitro studies also reported that cellular stress-induced production of IPP can activate Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [6, 39].

Our data also suggest that primary and secondary HMBPP exposure elicit greater absolute numbers of IFN-γ/TNF-α-coproducing Vγ2Vδ2 T cells than IPP only producing in infection. Likewise, HMBPP production in immunization appears to be better than IPP production for induction of Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells capable of inhibiting intracellular listeria in vitro. These implications are indeed consistent with the finding that HMBPP deficiency in listerial immunization leads to lower levels of pulmonary and systemic responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells.

IPP production in listerial immunization appears to favor “naive-like” and CD28+ early memory phenotypes, whereas listerial HMBPP differentiates more memory-like or CD28− late memory Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. The differing changes in phenotypes are consistent with the presumption that HMBPP in listeria stimulates Vγ2Vδ2 T cells more potently for clonal expansion and late memory [10] polarization than IPP production in infection. Whereas HMBPP-driven greater expansion and late memory dominance correlate with a stronger antilisterial response (Fig. 4), whether such late memory dominance represents an optional response is currently not known. In fact, it is argued that CD28+ early memory Vγ2Vδ2 T cells [10] may be less prone to “exhaustion” and more proliferative in response to phosphoantigen-based vaccination. Further studies may help to address these points.

Thus, whereas HMBPP production during respiratory listeria immunization or infection dominantly induces robust expansion, pulmonary trafficking/accumulation, effector function, and memory polarization of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells, IPP production can also elicit in vivo responses of Vγ2Vδ2 T effector cells with CD28+ early memory phenotype. Our findings may help to devise immune intervention of Vγ2Vδ2 T cells in vaccination or pulmonary infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (RO1 Grants HL64560, RR13601/OD015092, and AI106590, all to Z.W.C.).

We thank Dr. Lisa Halliday and the Biologic Resources Laboratory (BRL) staff for animal care and assistance with obtaining samples; Dr. Balaji Ganesh, Jewell Graves, and members of the Research Resources Center (RRC) Flow Cytometry Core for technical assistance with flow cytometry; and other members of the Z. W. Chen lab for technical assistance.

SEE CORRESPONDING EDITORIAL ON PAGE 948

- BAL

- bronchoalveolar lavage

- BALF

- bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- BCG

- bacille Calmette-Guérin

- BHI

- brain heart infusion

- BTN3A1

- butyrophilin 3A1

- HMBPP

- hydroxy-methyl-butenyl pyrophosphate

- IPP

- isopentenyl pyrophosphate

- Lm

- Listeria monocytogenes

- MEP

- microbial 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate

- Mtb

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- OD

- optical density

- RBC

- red blood cell

- TB

- tuberculosis

- WT

- wild-type

AUTHORSHIP

J.T.F. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. L.Y. and H.S. performed experiments. Z.W.C. designed experiments and wrote the paper. C.Y.C. and N.E.F. provided reagents or scientific expertise.

DISCLOSURES

All authors do not have any conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tanaka Y., Morita C. T., Tanaka Y., Nieves E., Brenner M. B., Bloom B. R. (1995) Natural and synthetic non-peptide antigens recognized by human gamma delta T cells. Nature 375, 155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jomaa H., Feurle J., Luhs K., Kunzmann V., Tony H. P., Herderich M., Wilhelm M. (1999) Vgamma9/Vdelta2 T cell activation induced by bacterial low molecular mass compounds depends on the 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 25, 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eberl M., Hintz M., Reichenberg A., Kollas A. K., Wiesner J., Jomaa H. (2003) Microbial isoprenoid biosynthesis and human gammadelta T cell activation. FEBS Lett. 544, 4–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kistowska M., Rossy E., Sansano S., Gober H. J., Landmann R., Mori L., De Libero G. (2008) Dysregulation of the host mevalonate pathway during early bacterial infection activates human TCR gamma delta cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 2200–2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Qin G., Mao H., Zheng J., Sia S. F., Liu Y., Chan P. L., Lam K. T., Peiris J. S., Lau Y. L., Tu W. (2009) Phosphoantigen-expanded human gammadelta T cells display potent cytotoxicity against monocyte-derived macrophages infected with human and avian influenza viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 200, 858–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gomes A. Q., Martins D. S., Silva-Santos B. (2010) Targeting gammadelta T lymphocytes for cancer immunotherapy: from novel mechanistic insight to clinical application. Cancer Res. 70, 10024–10027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heuston S., Begley M., Gahan C. G., Hill C. (2012) Isoprenoid biosynthesis in bacterial pathogens. Microbiology 158, 1389–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puan K. J., Jin C., Wang H., Sarikonda G., Raker A. M., Lee H. K., Samuelson M. I., Marker-Hermann E., Pasa-Tolic L., Nieves E., Giner J. L., Kuzuyama T., Morita C. T. (2007) Preferential recognition of a microbial metabolite by human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells. Int. Immunol. 19, 657–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh N., Cheve G., Avery M. A., McCurdy C. R. (2007) Targeting the methyl erythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway for novel antimalarial, antibacterial and herbicidal drug discovery: inhibition of 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase (DXR) enzyme. Curr. Pharm. Des. 13, 1161–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burk M. R., Mori L., De Libero G. (1995) Human V gamma 9-V delta 2 cells are stimulated in a cross-reactive fashion by a variety of phosphorylated metabolites. Eur. J. Immunol. 25, 2052–2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sireci G., Espinosa E., Di Sano C., Dieli F., Fournie J. J., Salerno A. (2001) Differential activation of human gammadelta cells by nonpeptide phosphoantigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 1628–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morita C. T., Jin C., Sarikonda G., Wang H. (2007) Nonpeptide antigens, presentation mechanisms, and immunological memory of human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells: discriminating friend from foe through the recognition of prenyl pyrophosphate antigens. Immunol. Rev. 215, 59–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tanaka Y., Sano S., Nieves E., De Libero G., Rosa D., Modlin R. L., Brenner M. B., Bloom B. R., Morita C. T. (1994) Nonpeptide ligands for human gamma delta T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 8175–8179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ryan-Payseur B., Frencher J., Shen L., Chen C. Y., Huang D., Chen Z. W. (2012) Multieffector-functional immune responses of HMBPP-specific Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells in nonhuman primates inoculated with Listeria monocytogenes DeltaactA prfA*. J. Immunol. 189, 1285–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ali Z., Shao L., Halliday L., Reichenberg A., Hintz M., Jomaa H., Chen Z. W. (2007) Prolonged (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate-driven antimicrobial and cytotoxic responses of pulmonary and systemic Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells in macaques. J. Immunol. 179, 8287–8296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sicard H., Ingoure S., Luciani B., Serraz C., Fournie J. J., Bonneville M., Tiollier J., Romagne F. (2005) In vivo immunomanipulation of V gamma 9V delta 2 T cells with a synthetic phosphoantigen in a preclinical nonhuman primate model. J. Immunol. 175, 5471–5480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gong G., Shao L., Wang Y., Chen C. Y., Huang D., Yao S., Zhan X., Sicard H., Wang R., Chen Z. W. (2009) Phosphoantigen-activated V gamma 2V delta 2 T cells antagonize IL-2-induced CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells in mycobacterial infection. Blood 113, 837–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen C. Y., Yao S., Huang D., Wei H., Sicard H., Zeng G., Jomaa H., Larsen M. H., Jacobs W.R., Jr., Wang R., Letvin N., Shen Y., Qiu L., Shen L., Chen Z. W. (2013) Phosphoantigen/IL2 expansion and differentiation of Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells increase resistance to tuberculosis in nonhuman primates. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vavassori S., Kumar A., Wan G. S., Ramanjaneyulu G. S., Cavallari M., El Daker S., Beddoe T., Theodossis A., Williams N. K., Gostick E., Price D. A., Soudamini D. U., Voon K. K., Olivo M., Rossjohn J., Mori L., De Libero G. (2013) Butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphorylated antigens and stimulates human gammadelta T cells. Nat. Immunol. 14, 908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang H., Henry O., Distefano M. D., Wang Y. C., Raikkonen J., Monkkonen J., Tanaka Y., Morita C. T. (2013) Butyrophilin 3A1 plays an essential role in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation of human Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells. J. Immunol. 191, 1029–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wei H., Huang D., Lai X., Chen M., Zhong W., Wang R., Chen Z. W. (2008) Definition of APC presentation of phosphoantigen (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate to Vgamma2Vdelta 2 TCR. J. Immunol. 181, 4798–4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Caccamo N., Meraviglia S., Scarpa F., La Mendola C., Santini D., Bonanno C. T., Misiano G., Dieli F., Salerno A. (2008) Aminobisphosphonate-activated gammadelta T cells in immunotherapy of cancer: doubts no more. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 8, 875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shen Y., Zhou D., Qiu L., Lai X., Simon M., Shen L., Kou Z., Wang Q., Jiang L., Estep J., Hunt R., Clagett M., Sehgal P. K., Li Y., Zeng X., Morita C. T., Brenner M. B., Letvin N. L., Chen Z. W. (2002) Adaptive immune response of Vgamma2Vdelta2+ T cells during mycobacterial infections. Science 295, 2255–2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dieli F., Poccia F., Lipp M., Sireci G., Caccamo N., Di Sano C., Salerno A. (2003) Differentiation of effector/memory Vdelta2 T cells and migratory routes in lymph nodes or inflammatory sites. J. Exp. Med. 198, 391–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Davey M. S., Lin C. Y., Roberts G. W., Heuston S., Brown A. C., Chess J. A., Toleman M. A., Gahan C. G., Hill C., Parish T., Williams J. D., Davies S. J., Johnson D. W., Topley N., Moser B., Eberl M. (2011) Human neutrophil clearance of bacterial pathogens triggers anti-microbial gammadelta T cell responses in early infection. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen Z. W. (2011) Immune biology of Ag-specific gammadelta T cells in infections. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2409–2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yan L., Qiu J., Chen J., Ryan-Payseur B., Huang D., Wang Y., Rong L., Melton-Witt J. A., Freitag N. E., Chen Z. W. (2008) Selected prfA* mutations in recombinant attenuated Listeria monocytogenes strains augment expression of foreign immunogens and enhance vaccine-elicited humoral and cellular immune responses. Infect. Immun. 76, 3439–3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Qiu J., Yan L., Chen J., Chen C. Y., Shen L., Letvin N. L., Haynes B. F., Freitag N., Rong L., Frencher J. T., Huang D., Wang X., Chen Z. W. (2011) Intranasal vaccination with the recombinant Listeria monocytogenes DeltaactA prfA* mutant elicits robust systemic and pulmonary cellular responses and secretory mucosal IgA. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 18, 640–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Begley M., Gahan C. G., Kollas A. K., Hintz M., Hill C., Jomaa H., Eberl M. (2004) The interplay between classical and alternative isoprenoid biosynthesis controls gammadelta T cell bioactivity of Listeria monocytogenes. FEBS Lett. 561, 99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eberl M., Altincicek B., Kollas A. K., Sanderbrand S., Bahr U., Reichenberg A., Beck E., Foster D., Wiesner J., Hintz M., Jomaa H. (2002) Accumulation of a potent gammadelta T-cell stimulator after deletion of the lytB gene in Escherichia coli. Immunology 106, 200–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Begley M., Bron P. A., Heuston S., Casey P. G., Englert N., Wiesner J., Jomaa H., Gahan C. G., Hill C. (2008) Analysis of the isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways in Listeria monocytogenes reveals a role for the alternative 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway in murine infection. Infect. Immun. 76, 5392–5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brown A. C., Eberl M., Crick D. C., Jomaa H., Parish T. (2010) The nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is essential and transcriptionally regulated by Dxs. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2424–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Borowski A. B., Boesteanu A. C., Mueller Y. M., Carafides C., Topham D. J., Altman J. D., Jennings S. R., Katsikis P. D. (2007) Memory CD8+ T cells require CD28 costimulation. J. Immunol. 179, 6494–6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Born W. K., Kemal Aydintug M., O'Brien R. L. (2013) Diversity of γδ T-cell antigens. Cell Mol Immunol. 10, 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wesch D., Peters C., Oberg H. H., Pietschmann K., Kabelitz D. (2011) Modulation of gammadelta T cell responses by TLR ligands. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2357–2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rincon-Orozco B., Kunzmann V., Wrobel P., Kabelitz D., Steinle A., Herrmann T. (2005) Activation of V gamma 9V delta 2 T cells by NKG2D. J. Immunol. 175, 2144–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shao L., Huang D., Wei H., Wang R. C., Chen C. Y., Shen L., Zhang W., Jin J., Chen Z. W. (2009) Expansion, reexpansion, and recall-like expansion of Vgamma2Vdelta2 T cells in smallpox vaccination and monkeypox virus infection. J. Virol. 83, 11959–11965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Joseph B., Goebel W. (2007) Life of Listeria monocytogenes in the host cells' cytosol. Microbes Infect. 9, 1188–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jameson J. M., Cruz J., Costanzo A., Terajima M., Ennis F. A. (2010) A role for the mevalonate pathway in the induction of subtype cross-reactive immunity to influenza A virus by human gammadelta T lymphocytes. Cell. Immunol. 264, 71–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]