Abstract

Women are found to be more religious than men and more likely to use religious coping. Only few studies have explored religious gender differences in more secular societies. This population-based study comprised 3,000 Danish men and women (response rate 45 %) between 20 and 40 years of age. Information about demographics, religiousness and religious coping was obtained through a web-based questionnaire. We organized religiousness in the three dimensions: Cognition, Practice and Importance, and we assessed religious coping using the brief RCOPE questionnaire. We found substantial gender differences in both religiousness and religious coping. Nearly, 60 % of the women believed in some sort of spirit or in God compared to 40 % of the men. Generally, both men and women scored low on the RCOPE scale. However, for respondents reporting high levels of religiousness, the proportion of men who scored high in the RCOPE exceeded the proportion of women in using positive and especially negative coping strategies. Also, in a secular society, women are found to be more religious than men, but in a subset of the most religious respondents, men were more inclined to use religious coping. Further studies on religious coping in secular societies are required.

Keywords: Religion, Religious coping, Gender, Secular society

Introduction

Gender differences within religion are well known, and women are generally found to be more religious than men (Francis 1997; Gallup and Lindsay 1999). This disparity between men and women also applies to Denmark (Ausker 2008; Iversen and Højsgaard 2005; Gundelach 2008b). Denmark is seen as one of the most secular societies in the world with very low rates of church attendance and religion only playing a minor role in public life (Zuckerman 2008). Despite the low rates of church attendance, 82 % of the Danish population are members of the Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church (Folkekirken), and the majority still call on the church to perform rites of passage as baptism, weddings and funerals (Iversen and Højsgaard 2005). It has been argued that the relationship to the church in Denmark is not as much an expression of Christianity and religiousness as a marker of social and cultural identity (Zuckerman 2008). However, the European Value Survey from 2008 regarding religiousness revealed that 53 % of Danish men and 66 % of Danish women stated that they believe in God (Gundelach 2008b).

In international research, women report a higher frequency of private prayer (Maselko and Kubzansky 2006), and a higher frequency of church attendance than men (World Values Survey 2006), men are more inclined to change their religious denomination than women are (Hayes 1996) and studies assessing the association between health and religion find that gender may modify the effects in this correlation (Maselko and Kubzansky 2006). Women and men also seem to have different images of God. Some studies report no gender differences in God images, whereas others find that women possess a more positive God image, emphasizing a personally relationship with a loving God, while men hold a more controlling God image, and focus on God’s power and judgment (Krejci 1998; Ozorak 1996).

As most religious systems are patriarchal in belief and practice, the more pronounced religiousness in women represents a paradox (Ozorak 1996). This inconsistency has been explained by women’s emphasize on the personal relationship with a loving God and the relationship with others in a religious community, through which women’s benefits of religious involvement are substantial (Ozorak 1996).

Religious coping has been a subject of study for the two decades, and religion is a well-documented beneficial coping strategy for some people (Pargament et al. 2000; Kraemer et al. 2009). Religious coping is not easily defined, but Pargament identifies five key religious functions: meaning, control, comfort, intimacy and life transformation that he covers is his religious coping scale, the RCOPE. He emphasizes that some forms of religious coping as punishing God reappraisal and Demonic reappraisal can be associated with distress (Pargament et al. 2000), and this is supported in American and Swiss studies finding positive religious coping correlated with positive health and psychological functioning, whereas negative religious coping was linked to negative outcomes (Bjorck and Thurman 2007; Kraemer et al. 2009). American studies find that people are more likely to use positive than negative religious coping (Pargament et al. 1998; Cotton et al. 2006).

The inclination to draw on positive or negative religious coping strategies in a crisis might be associated with the pre-existing image of God, and furthermore, the benefits of religious coping are shown to be associated with the level of religiousness in a person prior to the crisis (Krageloh et al. 2010). Specifically, strong spiritual, religious and personal beliefs are correlated with active coping, positive reframing and acceptance (Krageloh et al. 2010). Pargament underlines that it is not religion per se, but a personalized and integrated religiousness that generates the resources to endure the challenges (Pargament 1997). He emphasizes elements as a social religious context, a harmonious synthesis of beliefs, practices and motivations, and the accessibility of appropriate religious answers to the problems (Pargament 1997). Studies on coping strategies find that women are more likely to use religious coping than men (Pargament 1997; Cotton et al. 2006).

However, there is no agreed explanation for the gender differences in religiousness, and in a review from 1997, Francis concludes that numerous theories strive to explain the rationale behind, all lacking explicit evidence in empirical research (Francis 1997). Within the field of psychology of religion, the attachment theory has been applied as a possible explanation for gender differences in religiousness (Flannelly and Galek 2010). Like a child experiences a secure base provided by the primary caregiver, the “attachment figure,” God may serve as a secure base for the adult believer. Having a secure attachment to God seems to be associated with psychological well-being (Flannelly and Galek 2010). In extension to the attachment theory, gender differences have been explained in a Freudian perspective, suggesting that boys emerge from the Oedipus complex with ambivalent feeling toward the father, in contrast to girls who develop a more positive father attachment as he was their “first love object” (Francis 1997). Alternatively, socialization theories explain the dissimilarities between men and women as differences in social experience; the male role includes drive and aggressiveness and the female role embraces values more congruent with religious emphases as gentleness and nurturance (Francis 1997). In a similar vein, structural location theories claim that religious participation is considered a household activity performed by the wife at home and that teaching morals is also the mother’s task as the primary caregiver (Francis 1997). More recent theories suggest that religiosity is associated with gender orientation, namely the personality construct of femininity or masculinity regardless of actual gender. The later theory seems the best empirically supported (Francis 1997).

Only a few studies have explored religiousness and their related coping strategies in a secular society. One survey from 2008 assessed the use of religious coping in hospitalized Danish patients (Ausker 2008). Patients reported intensified beliefs and religious practices during hospitalization, and there was a statistically significantly larger increase in women compared to men (Ausker 2008).

Studies on religion and religious coping from countries with varying levels of religiousness are not easily compared, and it can been questioned whether scales as, for example, the RCOPE originating from the US where religion plays a major role in public life can be applied directly to more secularized societies. Nevertheless, in the present study, in lack of validated Danish instruments, we included the RCOPE, but only those respondents who stated that the crisis had caused them to think more about religious questions were asked to answer the RCOPE. We intended to explore whether perhaps some parts of the RCOPE would apply to the more religious part of Danish men or women.

This study is part of a larger survey on views and values initiated in 2009 with use of data from the Danish Twin Registry. In the present study, we aim to assess gender differences within various aspects of religiousness and religious coping. We organized religiousness in Fishman’s three dimensions: Cognition, Practice and Importance. Cognition covers conceptions of beliefs, Practice covers activities according to these conceptions of beliefs and Importance covers the feeling present in the individual (Gundelach 2008a). We also aim to assess how Danish men and women draw on religious coping in the event of a life crisis and to compare gender differences in coping related to various levels of religiousness.

Methods

This study about gender differences in religious beliefs and coping was part of a survey concerning attitudes and values in general. On October 1, 2009, an invitation to participate in a web-based survey was sent to 6,707 Danish twins born 1970–1989, identified in the Danish Twin Registry. The twins had earlier consented to participate in other surveys. This survey encompassed questions about health, smoking, alcohol intake, socio-economic status in childhood, educational level and connection to the labor market, marital status, political and ethical principles, experiences with a life crisis, religious beliefs and existential values; 9 questions about religious beliefs and behavior were obtained from the European Values Survey (EVS) (Gundelach 2008b), 13 questions about religious coping were obtained from the religious coping scale the RCOPE (Pargament et al. 2000) and 5 questions about religiousness and coping were constructed for this study. If preferred, the participants could request and return a printed questionnaire.

The RCOPE questionnaire classifies religious coping into positive coping strategies including a search for God’s support and negative coping strategies including uncertainty of God’s love or punishment by God (Pargament et al. 2000). We included 6 items with a positive dimension and 7 items with a negative dimension from the RCOPE. Only those respondents who stated that the crisis had caused them to think more about religious questions were asked to answer the RCOPE questions. For analyses assessing the use of religious coping associated with levels of religiousness, the 6 positive and the 7 negative RCOPE items were collapsed into one variable, respectively. As mentioned, we classified religious beliefs and behaviors into Fishman’s three dimensions: Cognition, Practice and Importance (Gundelach 2008a). Perception of God and believing in life after death were categorized as Cognition; frequency of church attendance and prayer were categorized as Practice; the importance of God and finding comfort and strength in religion were categorized as Importance. For analyses on the association between gender and religiousness, the responses were categorized in “Yes,” “No” and “Do not know,” where the “Yes” category included all levels of beliefs and frequencies of religious activities, and the “No” category included those who answered with absolute refusal. The questions “How important is God in your life?” “Did the crisis cause you to think more about religious questions?” and “Did the crisis cause you to have greater faith in life after death?” had response options on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “No, not at all” to 10 “Yes, definitely.” The following explanatory covariates were included in the analyses: age (continuous), educational level in four categories [none (reference), <3, 3–4 and more than 4 years] and the dichotomous variables; living with a partner, having children, good self-rated health, having experienced a crisis and having a chronic disease or cancer (verified by a medical doctor).

Associations between gender and religiousness classified into Cognition, Practice and Importance were expressed in terms of relative risks (RR) with 95 % confidence interval estimated by logistic regression adjusting for above explanatory covariates. For the matched case/co-twin design, the odds ratio (OR) was estimated by conditional logistic regression using the opposite-sex twin pair as the unit of analysis and estimates the gender differences within twin pairs. STATA, version 11.2, was used in the processing of data.

Results

A total of 3,686 twins completed the survey by February 16, 2010, resulting in a response rate in the overall study of 55 %. The mean age was 29.1 (SD 6.2), and 54 % of the respondents were women. Only 34 twins returned the printed questionnaire. The section of the questionnaire regarding beliefs and existential values was completed by 3,000 twins, resulting in a response rate of 45 %, and for this part of the survey, 60 % of these respondents were women. The large majority of the respondents were members of the Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church (82.6 %), corresponding exactly to the national level (Warburg and Jacobsen 2007). Nearly twice as many men as women were not a member of any religious denomination (Table 1).

Table 1.

Do you belong to a religious denomination?

| The Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church |

Catholic | Muslim | Other* | Not a member | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 1,534 (85.5) | 13 (0.7) | 4 (0.2) | 37 (2.1) | 205 (11.5) |

| Men | 943 (78.3) | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 11 (0.9) | 245 (20.3) |

Numbers (percentages) within gender

Jew, Hindu, Jehovah’s witnesses, Buddhist, etc

Asked about their perception of God, 136 (7.6 %) women stated that they know God really exists, compared to 59 (4.9 %) men, (P = 0.003). A large percentage of both men and women reported that they do not believe in a personal God, but they do believe in some sort of spirit; 588 women (32.8 %) and 249 men (20.7 %), (P < 0.001). In Table 2, people who answered with absolute rejection of the different aspects of religiousness were grouped in the No category, and people who answered yes to some or a high degree of religiousness were categorized in the Yes category. In all three dimensions of Cognition, Practice and Importance, men were statistically significantly less religious than women (Table 2). Furthermore, the percentage of men who answered “Do not know” were generally smaller than the percentage of women. The ratio between men and women is seen in the relative risk (RR), showing the probability of answering yes in women compared to men, in crude analyses and in analyses adjusting for age, chronic disease, having children, living with a partner, self-rated health, educational level and having experienced a crisis. In these analyses, the “Do not know” answers were excluded. A specific case/co-twin analysis was performed in twin pairs of opposite sex with odds ratios for the female twin being more religious than the male twin. Belief in God, prayer and importance of God remained statistically significant despite small numbers in this analysis.

Table 2.

Religiousness in Danish men and women

| Yes | No | Do not know |

RR | Adjusted RR* | Matched OR case-co-twin |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognition | ||||||

| Do you believe in God? | ||||||

| Women | 658 (36.8) | 710 (39.6) | 423 (23.6) | |||

| Men | 325 (27.0) | 690 (57.3) | 189 (15.7) | 1.50 (1.35–1.67) | 1.46 (1.30–1.64) | 1.89 (1.04–3.56) |

| Do you believe in life after death? | ||||||

| Women | 674 (37.6) | 640 (35.8) | 477 (26.6) | |||

| Men | 281 (23.3) | 670 (55.7) | 253 (21.0) | 1.74 (1.55–1.94) | 1.71 (1.51–1.93) | 0.95 (0.49–1.85) |

| Do you believe in re-incarnation? | ||||||

| Women | 326 (18.2) | 977 (54.5) | 488 (27.3) | |||

| Men | 135 (11.2) | 843 (70.0) | 226 (18.8) | 1.81 (1.51–2.17) | 1.79 (1.46–2.18) | 1.25 (0.44–3.64) |

| Practice | ||||||

| Do you ever attend religious services? | ||||||

| Women | 1,287 (71.8) | 504 (28.1) | 2 (0.1) | |||

| Men | 713 (59.2) | 488 (40.5) | 4 (0.3) | 1.21 (1.15–1.28) | 1.00 (0.71–1.42) | 0.67 (0.19–2.10) |

| Do you ever pray to God outside religious services? | ||||||

| Women | 969 (54.0) | 797 (44.5) | 27 (1.5) | |||

| Men | 460 (38.2) | 733 (61.0) | 10 (0.8) | 1.42 (1.31–1.55) | 1.37 (1.25–1.50) | 1.58 (1.00–2.52) |

| Do you have your own way of connecting with the divine? | ||||||

| Women | 1,296 (72.4) | 321 (17.9) | 174 (9.7) | |||

| Men | 682 (56.6) | 378 (31.4) | 144 (12.0) | 1.25 (1.18–1.31) | 1.23 (1.16–1.30) | 1.30 (0.79–2.17) |

| Importance | ||||||

| Is God important in your life? | ||||||

| Women | 1,225 (68.4) | 529 (29.5) | 37 (2.1) | |||

| Men | 610 (50.6) | 581 (48.3) | 13 (1.1) | 1.51 (1.28–1.77) | 1.43 (1.19–1.71) | 2.07 (1.08–4.12) |

| Do you find that you get strength and comfort from religion? | ||||||

| Women | 457 (25.5) | 1,089(60.8) | 245 (13.7) | |||

| Men | 224 (18.6) | 891 (74.0) | 245 (7.4) | 1.47 (1.28–1.69) | 1.35 (1.16–1.58) | 1.20 (0.63–2.29) |

Numbers (%) within gender

Crude and adjusted RR with 95 % CI for women answering yes compared to men. OR from matched case/co-twin analyses

Adjusted for age, chronic disease or cancer, having children, living with a partner, self-rated health, educational level and having experienced a crisis

When asked in more detail about their beliefs and perceptions of God, the percentages of men and women who were in doubt or answered I do not know were comparable (Table 3). Nearly 60 % of the women had a kind of belief in some sort of spirit or in God compared to 40 % of the men.

Table 3.

Levels of belief

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| I do not believe in some sort of spirit or in God | 273 (15.2) | 392 (32.6) |

| I do not know/I am in doubt | 447 (25.0) | 314 (26.1) |

| I believe in some sort of spirit, but not in a personal God | 412 (23.0) | 171 (14.2) |

| I believe in God | 523 (29.2) | 267 (22.2) |

| I know God really exists | 136 (7.6) | 59 (4.9) |

Numbers and percentages

Only 47 (2.6 %) women and 27 (2.2 %) men reported attending a religious service weekly and only 55 (3.1 %) women and 40 (3.3 %) men reported attending a religious service once a month. In this group of frequent church attendance, at least monthly, men and women were equally represented with 5.6 % of the men and 5.7 % of the women. In order to uncover any variation in religiousness over time, the respondents were asked to state the frequency of church attendance today and when they were 12 years old (Table 4). With regard to church attendance, 260 (14.7 %) women reported a decrease in the frequency of church attendance from childhood to adulthood, while 138 (7.8 %) women reported an increase in frequency of church attendance and 1,375 (77.5 %) women reported no change. Men stated similar changes; 212 (17.8 %) men reported a decrease, 97 (8.1 %) an increase and 882 (74.1 %) no difference in the frequency of church attendance.

Table 4.

Changes in the frequency of church attendance from 12 years of age to adulthood

| 12 years old | Presently |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| How often did you attend church? | At least once a month | On specific holidays* | Never |

| Women | |||

| At least once a month | 72 (29.7) | 143 (59.1) | 27 (11.2) |

| On specific holidays* | 24 (2.3) | 917 (88.9) | 90 (8.7) |

| Never | 5 (1.0) | 109 (21.9) | 384 (77.1) |

| Men | |||

| At least once a month | 35 (28.9) | 60 (49.6) | 26 (21.5) |

| On specific holidays* | 24 (3.6) | 517 (77.5) | 126 (18.9) |

| Never | 8 (2.0) | 65 (16.1) | 330 (81.9) |

Numbers (%) within gender

On specific holidays or once a year or less

Asked about the frequency of praying outside a religious service, 92 (5.1 %) women and 47 (3.9 %) men replied praying every day and 237 (13.2 %) women and 106 (8.8 %) men replied praying at least once a month.

Statistically significantly more women than men reported having experienced a crisis; 1,221 (68 %) women and 681 (57 %) men (P < 0.001). Furthermore, women reported that the crisis caused them to think more about religious questions, with a mean score of 3.2 (95 % CI 3.0–3.3) compared to a mean score for men of 2.9 (95 % CI 2.7–3.1), and statistically significantly more women (12.7 %) than men (8.0 %) stated that the crisis made them see themselves to a higher degree as believers than before the crisis (P = 0.008).

Finally, women also stated that the crisis gave them a greater faith in life after death with a mean score of 3.0 (95 % CI 2.9–3.2) compared to a mean score of 2.3 (95 % CI 2.1–2.5) for men (P < 0.001).

If the crisis caused the respondents to think more about religious issues, they were asked to answer the RCOPE questions regarding how they thought about God in relation to the crisis and what they did to manage the crisis with reference to religious coping (Table 5). Between 1,824 and 1,852 respondents answered the RCOPE questions and men and women showed only small discrepancies. Only few respondents reported coping strategies including negative God images.

Table 5.

Use of religious coping in a crisis, numbers and percentages within gender

| Not at all | To some degree | Very much | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive dimensions | ||||

| Looked for a stronger connection with God | ||||

| Women | 891 (77.0) | 211 (18.2) | 56 (4.8) | |

| Men | 535 (80.3) | 100 (15.0) | 31 (4.7) | 0.202 |

| Sought God’s love and care | ||||

| Women | 837 (71.5) | 239 (20.5) | 94 (8.0) | |

| Men | 537 (80.6) | 80 (12.0) | 49 (7.4) | <0.001 |

| Sought help from God in letting go of my anger | ||||

| Women | 917 (78.7) | 174 (15.0) | 73 (6.3) | |

| Men | 555 (83.5) | 63 (9.5) | 47 (7.0) | 0.003 |

| Tried to see how God might be trying to strengthen me in this situation | ||||

| Women | 859 (73.6) | 197 (16.9) | 111 (9.5) | |

| Men | 514 (77.3) | 92 (13.8) | 59 (8.9) | 0.178 |

| Asked forgiveness for my sins | ||||

| Women | 1,010 (85.9) | 119 (10.1) | 47 (4.0) | |

| Men | 570 (85.3) | 58 (8.7) | 40 (6.0) | 0.105 |

| Focused on religion to stop worrying about my problems | ||||

| Women | 1,052 (89.9) | 91 (7.8) | 27 (2.3) | |

| Men | 606 (91.7) | 39 (5.9) | 16 (2.4) | 0.322 |

| Negative dimensions | ||||

| Wondered why God had abandoned me | ||||

| Women | 1,029 (87.0) | 107 (9.0) | 47 (4.0) | |

| Men | 597 (89.4) | 45 (6.7) | 26 (3.9) | 0.217 |

| Felt punished by God for my lack of devotion | ||||

| Women | 1,107 (93.7) | 59 (5.0) | 15 (1.3) | |

| Men | 632 (94.5) | 28 (4.2) | 9 (1.3) | 0.726 |

| Wondered what I did for God to punish me | ||||

| Women | 972 (82.2) | 152 (12.9) | 58 (4.9) | |

| Men | 575 (86.0) | 65 (9.7) | 29 (4.3) | 0.100 |

| Questioned God’s love for me | ||||

| Women | 1,041 (88.4) | 101 (8.6) | 35 (3.0) | |

| Men | 597 (89.1) | 47 (7.0) | 26 (3.9) | 0.303 |

| Wondered whether my church had abandoned me | ||||

| Women | 1,156 (98.2) | 11 (0.9) | 10 (0.9) | |

| Men | 647 (96.6) | 16 (2.4) | 7 (1.0) | 0.039 |

| Believed the devil was responsible for my situation | ||||

| Women | 1,140 (96.5) | 30 (2.5) | 12 (1.0) | |

| Men | 639 (95.4) | 18 (2.7) | 13 (1.9) | 0.247 |

| Questioned the power of God | ||||

| Women | 966 (83.1) | 129 (11.1) | 68 (5.8) | |

| Men | 565 (85.4) | 55 (8.3) | 42 (6.3) | 0.159 |

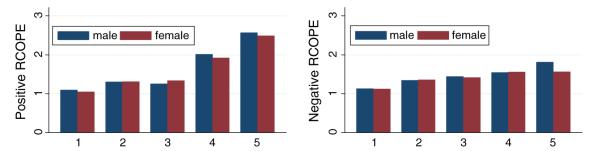

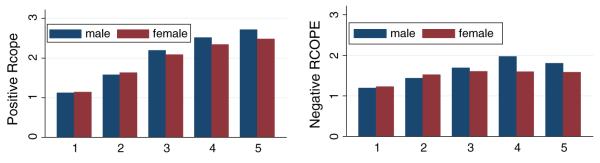

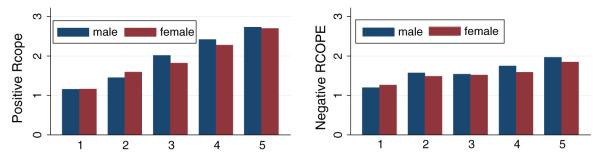

Given that only 25.5 % of the women and 18.6 % of the men answered that they get strength and comfort from religion (Table 2), we assessed the use of religious coping associated with the levels of religiousness. For these analyses, we collapsed the RCOPE items into one positive and one negative coping strategy, and we chose the one item from each of the three dimensions: Cognition, Practice and Importance that remained statistically significant in the matched case/co-twin analyses; belief in God, prayer and importance of God (Table 2). Figures 1, 2 and 3 show that in the categories with high levels of religiousness, the proportion of men who score high in RCOPE exceeded the proportion of women. This was valid for both positive and negative coping strategies, but a little more pronounced in the negative coping strategies.

Fig. 1.

Use of positive or negative religious coping associated with levels of belief in God. 1 Do not believe in God or in some sort of spirit, 2 do not know/in doubt, 3 believe in some sort of spirit but not in God, 4 believe in God, 5 know God really exists

Fig. 2.

Use of positive or negative religious coping associated with frequency of prayer to God. 1 Never, 2 once a year or less, 3 monthly, 4 weekly, 5 daily

Fig. 3.

Use of positive or negative religious coping associated with levels of importance of God. From (1) not important to (5) very important

Table 6 shows the numbers and percentages of respondents who answered “very much” in the positive and negative RCOPE strategy, respectively, according to their experiences with life crises. We refrained from statistical testing due to small numbers. Both men and women who had experienced the death of a child or a partner seemed to use the negative RCOPE strategies the most.

Table 6.

Numbers and percentages of men and women who answered that they used the strategies presented in the RCOPE “very much” associated with specific crisis experiences

| Specific crisis experience | Positive RCOPE |

Negative RCOPE |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Death of a child | Yes | 2 (15.4) | 4 (18.2) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (40.9) |

| Death of partner | Yes | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (16.7) |

| Death of mother | Yes | 7 (13.2) | 13 (12.3) | 8 (15.4) | 13 (12.0) |

| Death of father | Yes | 12 (14.0) | 24 (15.5) | 9 (10.6) | 24 (15.5) |

| Life-threatening disease | Yes | 4 (15.4) | 12 (22.2) | 6 (22.2) | 9 (16.4) |

| Divorce of parents | Yes | 26 (14.5) | 39 (11.9) | 15 (8.3) | 28 (8.4) |

Discussion

In this population-based study of religiousness in Danish men and women, we found remarkable gender differences in religiousness, in the ways of applying religious coping strategies and in the use of positive and negative religious coping.

Women reported higher levels of religiousness within all three dimensions of Cognition, Practice and Importance, and men were more often not religious at all. These findings remained statistically significant in analyses adjusting for important confounders. In the case/co-twin analyses, belief in God, prayer and importance of God remained statistically significant despite small numbers. In the case/co-twin design, the male twin is compared to the female twin in the same twin pair, and as twins are reared in the same environment both known and unknown confounders are inevitably included in the analyses. We found no gender differences among the small group of respondents who attended church at least monthly or in changes in church attendance from 12 years of age to adulthood.

The proportion of respondents answering positively to religious questions in our study were smaller than the proportion of Danes in the European Values Study (EVS) from 2008, even when we compared the same age groups (Gundelach 2008b). In the Practice and Importance dimensions, small and moderate differences were seen, but in the Cognition dimension, a large discrepancy was seen in the question “Do you believe in God; yes/no/don’t know” where 62 % of the women and 43 % of the men in the EVS answered yes compared to 37 % of the women and 27 % of the men in the our data. We found no obvious explanation of this divergence. Still, respondents in web-based questionnaires might be a selected group. The present study is part of a larger survey on views and values including only twins in order to enable studies on heritability. Other twin studies on religiousness do not report discrepancy between twins and singletons in regard to religiousness (Koenig 2011). Conclusions from twin studies assume that twins are representative for the population at large and that they do not differ systematically from singletons with respect to personality. Studies assessing individual psychological traits conclude that twins are just ordinary people with respect to personality (Johnson et al. 2002), and that they show similar academic performance in adolescence to that of singletons (Christensen et al. 2006). Being a twin, on the other hand, decreases the risk of committing suicide (Tomassini et al. 2003), and also, twins tend to marry later and have fewer divorces (Petersen et al. 2011). Hence, twins might differ from singletons in regard to attachment, and evidently, it needs to be explored whether this could influence twins’ inclination to believe in God. Still, the difference in religiousness between men and woman was similar in our data and in the EVS (Gundelach 2008b).

As shown by Zuckerman, the Danish society differs remarkably from most other societies with respect to the public role of religion (Zuckerman 2008). The Danish National Evangelical Lutheran Church is a state church, and 82.6 % of the Danish population are members, paying taxes to the church. Still, only 2.6 % of the women and 2.2 % of the men in the present study attend a religious service weekly, and as much as 44.5 % of the women and 60.9 % of the men stated that they never pray to God. Furthermore, as much as 25.0 % of the women and 26.1 % of the men stated that they did not know, whether they believed in God or not. Consequently, the present results are not easily compared with findings from countries with fundamentally dissimilar structures of religiousness as, for example, the USA where in 2006, 36.5 % of women and 28.7 % of men between 30 and 49 years of age went to church at least once a week, and only 8.8 % of women and 19.2 % of men never prayed to God (World Values Survey 2006). In a survey from 1994, 64 % of Americans stated that they know God really exists (Gallup and Lindsay 1999), compared to 7.6 % of the Danish women and 4.9 % of the Danish men in the present study (Table 3). Only 5 % of the Americans did not believe in God (Gallup and Lindsay 1999), in contrast to 15.2 % of Danish women and 32.6 % of Danish men (Table 3).

Nevertheless, Danish men and women are not completely irreligious. When asked which statement fitted their beliefs the best; “I believe in God/I don’t believe in God/I don’t know,” 983 (32.8 %) picked “I believe in God.” When asked in further detail in the following question about their perception of God, 837 (28.0 %) picked “I do not believe in a personal God, but I do believe in some sort of higher spirit.” In fact, there was an overlap between the answers in these two questions, as 254 (25.8 %) of those who said they believed in God, also said that they did not believe in a personal God (data not shown). Thus, in a Danish context, God is not necessarily a personal God and can be understood in a broader perspective and believing in God does not necessarily lead to religious behaviors as praying or going to church. Similar complex findings are presented in other Danish studies (Iversen and Højsgaard 2005).

For women, the experiences of a crisis had a deeper religious impact than it did for men; a crisis leads women to think more about religious questions, to see themselves to a higher degree as believers and to have a higher belief in life after death. Ausker et al. found similar results regarding women seeing themselves to a higher degree as believers during hospitalization, but they found no difference regarding belief in life after death before and during hospitalization (Ausker 2008).

Approximately 1,800 respondents answered the RCOPE questions and between 71 % and 98 % stated that they did not at all use these specific coping strategies in case of a crisis and especially the negative coping strategies seemed less prevalent. The preference for positive religious coping strategies is also found in American studies (Cotton et al. 2006; Pargament et al. 1998). Overall, men and women showed only small discrepancies in use of religious coping, and when we looked at the association between levels of religiousness and the use of religious coping, respondents who scored high in religiousness in all three dimensions of Cognition, Practice and Importance also scored high in use of religious coping. In fact, men scored higher than women in the use of positive and especially in the use of negative religious coping strategies in the subset of respondents with high levels of religiousness. Even though numbers are too small for statistical testing, the tendency found by using the RCOPE of a swapped association between gender and religiousness among the most religious Danes is interesting and requires further investigation.

The findings that men tend to use negative religious coping strategies to a higher degree than women are in line with the specific God image men seem to hold (Krejci 1998; Ozorak 1996). Having a more controlling God image and focusing on God’s power and judgment correspond well with the negative coping items as “Felt punished by God for my lack of devotion” or “Wondered what I did for God to punish me.” According to the attachment theory, a child experiences a secure base provided by the primary caregiver, the “attachment figure,” and likewise, God may serve as a secure base for the adult believer (Flannelly and Galek 2010). The Freudian perspective suggests that boys emerge from the Oedipus complex with ambivalent feeling toward the father (Francis 1997), and consequently, men may be more prone to use the negative religious coping strategies.

It has been argued that the benefits of religious coping are associated with the level and character of religiousness in a person prior to the crisis (Krageloh et al. 2010), and that applying religious coping is correlated with religious importance and participation (Maynard et al. 2001). In this light, it is not surprising that only a smaller proportion of the respondents actually use religious coping strategies. A study from New Zealand demonstrates that for people who scored more than one standard deviation above the mean in the WHOQOL-SRPB questionnaire, religious coping was correlated with active coping, positive reframing and acceptance. The WHOQOL-SRPB assesses the strength of a person’s spiritual, religious and personal beliefs. For people with a WHOQOL-SRPB below the mean, religious coping was correlated with emotional and instrumental support, but also with maladaptive strategies as denial, venting and behavioral disengagement (Krageloh et al. 2010). Correspondingly, for people with a religious affiliation, religious coping was positively correlated with acceptance and negatively correlated with substance abuse, while for people without a religious affiliation, religious coping was correlated with denial (Krageloh et al. 2010).

Pargament argues that attachment with a personal God is important for beneficial use of religious coping, just as being a part of a religious community is (Pargament 1997). In the present study, only a small minority were engaged in religious communities with regular church attendance, and only approximately one-third of the respondents believed in a personal God (Table 3). Therefore, it was a predictable finding that the respondents scored low on the RCOPE (Table 5). However, when we assessed religious coping associated with a specific crisis, the outcomes were surprising (Table 6). We explored respondents who answered that they used one or more of the religious coping strategies very much. Numbers were small in the subset of respondents who had experienced a crisis, but the trend was obvious. In the general sample, only 13.9 % reported using positive RCOPE strategies very much and only 10.1 % reported using the negative RCOPE strategies very much. In the subset of respondents who had experienced a crisis, between 0.0 and 22.2 % reported using positive religious coping strategies very much, and between 8.3 and 40.9 % reported using negative religious coping very much. The loss of a child or a partner led to the highest score for both men and women. Accordingly, Danish men and women do in fact turn to religious coping when facing a crisis. This is also in accordance with the findings of Ausker et al., who found that Danish patients reported intensified beliefs and religious practices during hospitalization. Ausker et al. did not use the RCOPE questionnaire, but their questions were phrased as neutral religious coping strategies.

The RCOPE is developed in the USA, and hence, the phrasings of the questions in the RCOPE are embedded in a culture with a religious discourse that might be unfamiliar to most people in Denmark today. Studies on religious coping in the USA show higher scores on the RCOPE than the present study (Cotton et al. 2006). As shown in this study, religiousness and religious coping still exists in Denmark but to further study religious coping in Denmark, we need to develop a religious language more suitable for the specific Danish secular setting.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by US National Institute on Aging grant NIA-PO1-AGO31719, the Health Insurance Foundation and the Aase and Ejnar Danielsen Foundation.

Contributor Information

Dorte Hvidtjørn, Epidemiology Unit, Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Jacob Hjelmborg, Department of Biostatistics, Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Axel Skytthe, Epidemiology Unit, Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Kaare Christensen, Epidemiology Unit, Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Niels Christian Hvidt, Research Unit of Health, Man and Society, Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

References

- Ausker N. Danske patienter intensiverer eksistentielle tanker og religiøst liv. Ugeskrift for Læger. 2008;170(21):1828–1833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorck JP, Thurman JW. Negative life events, patterns of positive and negative religious coping, and psychological functioning. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2007;46(2):159–167. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Petersen I, Skytthe A, Herskind AM, McGue M, Bingley P. Comparison of academic performance of twins and singletons in adolescence: Follow-up study. BMJ. 2006;333(7578):1095. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38959.650903.7C. doi:10.1136/bmj.38959.650903.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Puchalski CM, Sherman SN, Mrus JM, Peterman AH, Feinberg J, et al. Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:S5–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00642.x. doi:10.1111/j.1535-1497.2006.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannelly KJ, Galek K. Religion, evolution, and mental health: Attachment theory and ETAS theory. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010;49(3):337–350. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9247-9. doi:10.1007/s10943-009-9247-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis L. The psychology of gender differences in religion: A review of empirical research. Religion. 1997;27:81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Folkekirken. Folkekirken . Folkekirken.dk. Den Danske Folkekirke; [web page]. Available from http://www.folkekirken.dk/ [Google Scholar]

- Gallup GJ, Lindsay DM. Trends in the US. Morehouse pub; Harrisburg: 1999. Surveying the religious landscape. [Google Scholar]

- Gundelach P. I hjertet af danmark. Hans Reitzels forlag; Copenhagen: 2008a. Institutioner og mentaliteter; pp. 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gundelach P. Department of Sociology. University of Copenhagen; Denmark: 2008b. European Values Study 2008: Denmark (EVS 2008) [Google Scholar]

- Hayes BC. Gender differences in religious mobility in Great Britain. The British Journal of Sociology. 1996;47(4):643–656. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen HR, Højsgaard MT. Gudstro i Danmark. 1st ed ANIS; København: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Krueger RF, Bouchard TJ, Jr, McGue M. The personalities of twins: Just ordinary folks. Twin Research: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies. 2002;5(2):125–131. doi: 10.1375/1369052022992. doi:10.1375/1369052022992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig L. The behavioral genetics of religiousness. Theology and Science. 2011;9(2):199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer B, Winter U, Hauri D, Huber S, Jenewein J, Schnyder U. The psychological outcome of religious coping with stressful life events in a Swiss sample of church attendees. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2009;78(4):240–244. doi: 10.1159/000219523. doi:10.1159/000219523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krageloh CU, Chai PP, Shepherd D, Billington R. How religious coping is used relative to other coping strategies depends on the individual’s level of religiosity and spirituality. Journal of Religion and Health. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9416-x. doi:10.1007/s10943-010-9416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krejci MJ. Gender comparison of god schemas: A multidimensional scaling analysis. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 1998;8(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Kubzansky LD. Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: Results from the US General Social Survey. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(11):2848–2860. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard EA, Gorsuch RL, Bjorck JP. Religious coping style, concept of god, and personal religious variables in threat, loss, and challenge situations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40(1):65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ozorak EW. The power, but not the glory: How women empower themselves through religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1996;35(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping. The Guildford Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;56(4):519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519:AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37(4):710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen I, Martinussen T, McGue M, Bingley P, Christensen K. Lower marriage and divorce rates among twins than among singletons in Danish birth cohorts 1940–1964. Twin Research and Human Genetics : The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies. 2011;14(2):150–157. doi: 10.1375/twin.14.2.150. doi:10.1375/twin.14.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomassini C, Juel K, Holm NV, Skytthe A, Christensen K. Risk of suicide in twins: 51 year follow up study. BMJ. 2003;327(7411):373–374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7411.373. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7411.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg M, Jacobsen B. Tørre tal om troen. Religionsdemografi i det 21. århundrede. Forlaget Univers; 1. udgave. 1. oplag: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Values Survey 2006 Available from http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/

- Zuckerman P. In: Samfund uden Gud. Bek-Pedersen K, translator. Univers; 2008. [Google Scholar]