Abstract

Background

The widespread occurrence of melatonin in prokaryotes as well as eukaryotes indicates that this indoleamine is considerably old. This high evolutionary age has led to the development of diverse functions of melatonin in different organisms, such as the detoxification of reactive oxygen species and anti-stress effects. In insects, i.e. Drosophila, the addition of melatonin has also been shown to increase the life span of this arthropod, probably by reducing age-related increasing oxidative stress.

Although the presence of melatonin was recently found to exist in the ecological and toxicological model organism Daphnia, its function in this cladoceran has thus far not been addressed. Therefore, we challenged Daphnia with three different stressors in order to investigate potential stress-response attenuating effects of melatonin. i) Female and male daphnids were exposed to melatonin in a longevity experiment, ii) Daphnia were confronted with stress signals from the invertebrate predator Chaoborus sp., and iii) Daphnia were grown in high densities, i.e. under crowding-stress conditions.

Results

In our experiments we were able to show that longevity of daphnids was not affected by melatonin. Therefore, age-related increasing oxidative stress was probably not compensated by added melatonin. However, melatonin significantly attenuated Daphnia’s response to acute predator stress, i.e. the formation of neckteeth which decrease the ability of the gape-limited predator Chaoborus sp. to handle their prey. In addition, melatonin decreased the extent of crowding-related production of resting eggs of Daphnia.

Conclusions

Our results confirm the effect of melatonin on inhibition of stress-signal responses of Daphnia. Until now, only a single study demonstrated melatonin effects on behavioral responses due to vertebrate kairomones, whereas we clearly show a more general effect of melatonin: i) on morphological predator defense induced by an invertebrate kairomone and ii) on life history characteristics transmitted by chemical cues from conspecifics. Therefore, we could generally confirm that melatonin plays a role in the attenuation of responses to different stressors in Daphnia.

Keywords: Daphnia, Chaoborus kairomone, Melatonin, Crowding, Longevity, Stress response

Background

Melatonin is a molecule which can be found in many organisms from prokaryotes to eukaryotes. It was first discovered as a skin-lightening substance that influences the aggregation of the pigment melanin [1]. Since then, many more functions of melatonin have been found in vertebrates, invertebrates and unicellular organisms (reviewed in [2]): These functions include detoxification of reactive oxygen species (ROS), adjustment of the circadian clock to the environmental light regime, regulation and synchronization of cell physiology, mediation of photoperiodic information and anti-stress effects. The administration of melatonin is also being discussed as a strategy to slow aging and the initiation and progression of age-related disorders in humans [3]). The life span of Drosophila was extended significantly after continuous addition of melatonin to the rearing medium [4]. This might be due to the ability of melatonin to reduce oxidative stress and to stimulate important anti-oxidative enzymes [5], since aging is most probably a consequence of accumulated free radical damage [6].

In crustaceans, melatonin has been shown to have diverse physiological purposes (reviewed in [7]): Tilden et al. 2003 [8] have demonstrated that melatonin modulates locomotory activity, glucose/lactate levels and neurotransmitter release in crayfish. Melatonin also has an influence on limb regeneration in the fiddler crab Uca pugilator [9] and influences the regulation of the molting of the edible crab Oziotelphusa senex senex [10]. Also, a potential role of melatonin in connection with antioxidant defense systems has been discussed in the estuarine crab Neohelice granulate [11].

Melatonin has very recently been detected in the crustacean Daphnia [12], which is an important model organism in biological and especially in ecological studies [13]. Moreover, in Daphnia the highest concentration of melatonin was detected in the nervous system [12]. This situation is comparable to that of mammals, in which melatonin is synthesized in the pineal gland in the brain. Its synthesis has been shown to result from rhythmic transcription of genes of the circadian clock [14].

In Daphnia, it is unknown whether melatonin functions similarly or whether it has a different role in this model organism. Until now, only very few studies have tested the effects of melatonin on Daphnia. A significant decrease in the heart rate of D. magna due to melatonin has been observed [15], whereas no effect of melatonin on Daphnia sex determination has been found [16]. Bentkowski et al. 2010 [17] have demonstrated that diel vertical migration – a behavioral response to fish-predation pressure on Daphnia – was disturbed both in female and male Daphnia after addition of melatonin. This finding indicates that melatonin acts as a stress-signal inhibitor of responses to predation threat in Daphnia.

Here, we investigated whether melatonin attenuates the transmission of stress signals beyond behavioral response in Daphnia. To test for the generality of effects of melatonin on Daphnia, two different species were used: D. magna and D. pulex. We exposed Daphnia to three different stressors: Aging, predator cues and crowding. i) To test for a potential effect of melatonin on senescence of D. magna, male and female neonates were exposed to melatonin in a longevity experiment; the number of live and dead animals was counted over time. ii) Invertebrate predation pressure was simulated by exposure of D. pulex to extracts of larvae of Chaoborus sp., and Daphnia’s morphological stress response, i.e. neckteeth formation was analyzed in tests with or without addition of melatonin. iii) D. pulex were kept under moderate crowding conditions, causing density-dependent stress, and the number of ephippia and subitaneous neonates was determined for tests with or without addition of melatonin.

Methods

Cultures

Daphnia pulex clone Gerstel, which was isolated from a pond in Northern Germany [18], and Daphnia magna clone P132.85, originating from Pond Driehoek, The Netherlands [19], was cultivated for many generations at 20°C in membrane-filtered (0.2 μm), aged tap water. Fifteen animals per litre were kept under non-limiting food concentrations (2 mg C l−1) with Chlamydomonas klinobasis, originating from Lake Constance, Germany, as food alga. The light condition under which the animals were grown was a light–dark cycle of 12 h: 12 h. C. klinobasis was cultivated semi-continuously in cyanophycean medium [20] at 20°C at 130 μE m−2 s−1, with 20% of the medium exchanged every other day.

Longevity

In order to investigate a potential effect of melatonin on longevity of D. magna, third-clutch neonates – either males or females - were grown in two different treatments from birth to death. The experiment was performed in triplicates, either with 10 males or 20 females, in one litre of aged tap water with 2 mg C l−1 of C. klinobasis at 20°C. The control treatment consisted of pure medium, whereas 10−6 M melatonin was added in the other treatment as according to [17]. The animals were transferred to fresh medium every other day, at which time the number of live and dead animals was counted.

Predation pressure

Approximately 1000 Chaoborus sp. larvae were incubated for 24 hours in one liter of aged tap water. The incubation water containing Chaoborus kairomone was filtered through membrane filters (pore size: 0.45 mm). For bulk enrichment of the kairomone, a C18 solid-phase cartridge (10 g of sorbent, volume 60 ml, end-capped, Varian Mega Bond Elut, Agilent Technologies) was pre-conditioned with 50 ml 100% methanol, followed by 50 ml 1% methanol, prior to adding the sample. Methanol was added to the filtered incubation water containing Chaoborus kairomone to obtain a 1% concentration, and 1 l of sample was passed through the cartridge. The loaded cartridge was washed with 50 ml of ultrapure water with 1% methanol and then eluted with 50 ml of methanol. The eluates originating from 20 l of Chaoborus incubation water were pooled, evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator and resolved in 1 ml of absolute methanol.

To test for effects of melatonin on neckteeth production due to the presence of Chaoborus kairomone, D. pulex mothers were incubated in four different treatments: In the control treatment, one D. pulex mother carrying fourth-clutch eggs (yolk stadium [21]) was kept in 100 ml aged tap water with 2 mg C l−1C. klinobasis until the neonates were born. In the second treatment, 3.2 μl Chaoborus extract was provided before adding water and food once the solvent was evaporated. In the third treatment, 2 × 10−6 M melatonin was provided, and after evaporation of the solvent, food and water were added. In the fourth treatment, the D. pulex mothers were kept in medium to which both Chaoborus extract and melatonin were added. The experiment was run in five replicates. Directly after release of the neonates from the brood chamber, the number and intensity of the neckteeth were determined and ranged as according to [22]. In short: A fully developed neckteeth structure consisting of five neckteeth and a neck-keel with a pedestral was considered to be 100%. Each tooth was given an induction value of 10%. The formation of a neck-keel scored an additional 30% and a neck-keel with a pedestal added 50%.

Crowding

Reproduction experiments were performed to investigate whether melatonin attenuates stress responses due to crowding conditions. Therefore, in the control treatment, twelve new-born D. pulex were kept in 200 ml aged tap water with 2 mg C l−1C.klinobasis at 20°C. In the melatonin treatment, 5 × 10−6 M melatonin was provided and - after evaporation of the solvent - the medium was added. The melatonin concentration was five times higher than in the two other experiments to ensure that even in a high density all animals were influenced by melatonin; nevertheless the concentration was still in the range used by others [17]. The medium was exchanged every day. After seven days the number of animals was decreased to nine to avoid food limitation. The whole experiment was run in four replicates and lasted for 15 days, until all experimental animals had either produced three subitaneous clutches or two broods with resting eggs (embedded in ephippia). The number of subitaneous neonates and shed ephippia was determined.

Data analysis and statistics

Longevity

Longevity of D. magna females and males was evaluated by survival analyses using Kaplan-Meier as an estimator followed by log-rank tests testing for differences among survival curves.

Predation pressure

To test for differences in neckteeth development of neonates between melatonin and Chaoborus treatments, two-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were carried out followed by multiple comparisons (Tukey’s HSD); assumptions for ANOVA were met. All analyses were performed using the statistical software package R (version 3.0.2).

Crowding

Numbers of ephippia carrying Daphnia were analyzed using a generalized linear model (GLM) with logit function as the link function for binominal distribution. Numbers of offspring produced parthenogenetically were analyzed using a GLM with log function as the link function for quasi-Poisson distribution. If necessary, the models were fitted using quasi-Binomial or quasi-Poisson errors to compensate for over-dispersion [23]. To specify differences among treatment effects, the subsets of different broods were analyzed separately.

Results

Longevity

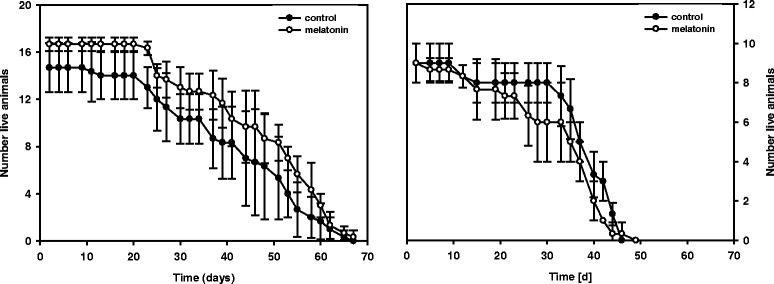

The experiment in which daphnids were or were not exposed to melatonin lasted from birth to natural death. Female D. magna lived significantly (ca. 20 d) longer than males (Figure 1; chi2 = 26.9, df = 1, p <0.001) but addition of melatonin did not change life span of females (chi2 = 2.1, df =1, p = 0.15) or of males (chi2 = 2.4, df =1, p = 0.12).

Figure 1.

Longevity of Daphnia . Life span of D. magna females (left) and males (right) grown on C. klinobasis with or without addition of melatonin (10−6 M) over time. Life span is depicted as number of live animals over time (n = 3, mean ± SD).

Predation pressure

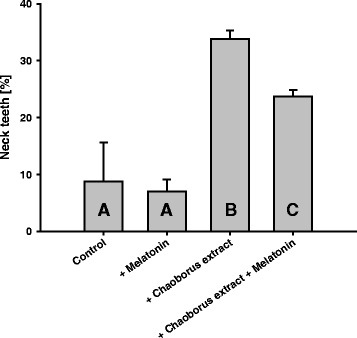

In the experiment in which the role of melatonin was tested on morphological D. pulex stress responses induced by Chaoborus extract, we found a modulating effect of melatonin on neckteeth development. In the absence of Chaoborus extract, newborns of control mothers and of melatonin-treated mothers produced neckteeth of less than 10%. In the presence of Chaoborus extract, all newborns generally showed a higher neckteeth production (Figure 2, Tukey’s HSD following 2-factorial ANOVA, p <0.05, Table 1); however, the neckteeth production of 30% significantly decreased under the additional influence of melatonin.

Figure 2.

Neckteeth formation. Neckteeth production by D. pulex newborns whose mothers were or were not incubated with Chaoborus kairomone and were fed with C. klinobasis with or without addition of melatonin. Different letters indicate significant differences between treatments (Tukey’s HSD after two-way ANOVA, p <0.05, n = 5).

Table 1.

Statistics of neckteeth formation

| df | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chaoborus (Ch) | 1, 8 | 94.0 | < 0.001 |

| Melatonin (M) | 1, 8 | 7.49 | 0.026 |

| Ch × M | 1, 8 | 3.72 | 0.09 |

Results of the two-factorial ANOVA (df = degrees of freedom) for the neckteeth formation of D. pulex which were or were not incubated with Chaoborus extract (factor “Chaoborus”) and with or without addition of melatonin (factor “Melatonin”).

Crowding

In the experiment under moderate crowding conditions, ephippia production was significantly affected by the factors “brood” (which indicates differences among subsequent ephippia broods) and “treatment” (i.e. with or without melatonin) (Table 2). Ephippia production was generally higher in the first than in the second brood (Figure 3). Melatonin significantly reduced the ephippia production, an effect which is mainly due to a significantly lower ephippia production in the melatonin treatment of the second ephippia brood (Table 2). The production of subitaneous eggs was different between subsequently parthenogenetically produced clutches and was additionally affected by the treatment with melatonin (Table 3). The clutch size increased over time and showed significantly higher offspring numbers in the melatonin treatment in the first and the third clutch (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Statistics of ephippia production

| Factor | df | Deviance | Residual deviance | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ephippia | Brood (B) | 1, 14 | 79.8 | 20.1 | < 0.001 |

| Melatonin(M) | 1, 13 | 5.17 | 15.0 | 0.023 | |

| B × M | 1, 12 | 1.85 | 13.1 | 0.17 | |

| Subset brood 1 | M | 1, 6 | 0.007 | 8.5 | 0.94 |

| Subset brood 2 | M | 1, 6 | 7.02 | 4.66 | < 0.01 |

Error distribution = quasi Binomial, link function = logit.

Results of the GLM analysis of the first and second ephippial brood (factor “Brood”) of D. pulex grown under moderate crowding conditions with or without melatonin (factor “Melatonin”).

Figure 3.

Crowding. Number of offspring from D. pulex grown under moderate crowding conditions with or without melatonin. Delineated is the number of ehippia from the first and second brood (left), and the number of live neonates from the first to the third clutch (right) per individual D. pulex mother. Stars indicate significance (n.s. = not significant) according to GLM (p <0.05, n = 4).

Table 3.

Statistics of neonate production

| Factor | df | Deviance | Residual deviance | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subitaneous eggs | Clutch (C) | 2, 21 | 64.4 | 30.7 | < 0.001 |

| Melatonin (M) | 1, 20 | 3.38 | 27.3 | 0.06 | |

| C × M | 2, 18 | 5.42 | 21.9 | 0.06 | |

| Subset clutch 1 | M | 1, 6 | 3.83 | 4.99 | 0.021 |

| Subset clutch 2 | M | 1, 6 | 0.23 | 14.5 | 0.72 |

| Subset clutch 3 | M | 1, 6 | 4.74 | 2.42 | < 0.001 |

Error distribution = quasi Poisson, link function = log.

Results of the GLM analysis of the first to third neonate clutches of D. pulex (factor “Clutch”) grown under moderate crowding conditions with or without melatonin (factor “Melatonin”).

Discussion

In several studies the effect of melatonin on longevity and aging has been examined (reviewed in [24]), and Reiter et al. [24] have stated that exogeneously administered melatonin may serve to increase longevity in invertebrates in general. For example in Drosophila, the life span was extended significantly after continuous addition of melatonin to the rearing medium [4].

Here, in contrast to the results of other recent observations [25], D. magna females and males of the same clone differed significantly in life span, with female daphnids outliving males. However, the addition of melatonin did not change the longevity of either sex of D. magna, contradicting earlier findings with the same species [3]. Izmaylov and Obukhova [26] found that in some generations of Drosophila an effect of melatonin on life span was either undetected or led to a toxic reduction in longevity. Similarly, the effect of melatonin on the life span of Daphnia might depend on the Daphnia clone and the concentration of melatonin added. Melatonin that is administered to a particular clone in an optimal dose might have had a positive influence on life span, whereas a higher melatonin concentration putatively would have had a toxic effect.

Since the results of the longevity experiment did not reveal any effects by melatonin, we further tested for putative short-time effects of melatonin under acute stress conditions. Although aging can be regarded as a process with increasing stress due to accumulated free radical damage [6], it does not constitute an acute stressor with immediate responses. Bentkowski et al. [17] postulated that melatonin might act as a stress signal inhibitor, since they found that addition of melatonin resulted in disturbed behavioral response of D. magna to kairomones released by a vertebrate predator, i.e. fish. Here, we tested whether this also holds true for stress responses to an invertebrate predator, i.e. larvae of the phantom midge Chaoborus sp. that induces morphological changes mediated by kairomones [27]. A conspicuous inducible morphological change in Daphnia caused by Chaoborus kairomone is the formation of neckteeth [22,28]: small structures on the back of the head which elongate handling time and thus increase the probability that Daphnia can escape from Chaoborus larvae [29]. Neckteeth are maximally developed in first to third instar neonates of D. pulex, and are completely absent in adults. From a certain size on, the animals become too large to fit into the prey pattern of this gape-limited predator, and thus neckteeth become unnecessary [30]. Therefore, we determined the neckteeth of first instar neonates from D. pulex directly after release from their mothers’ brood chamber. We found that treatment with Chaoborus extract resulted in increased neckteeth formation in comparison to the control, regardless if melatonin was added or not. Confirming our initial hypothesis, the presence of melatonin in the second Chaoborus treatment led to a significantly lower expression of neckteeth in D. pulex neonates. Therefore, the response to invertebrate predator signals was attenuated by addition of melatonin. However, neckteeth expression was not reduced to the level of the control treatment. This might have had two causes; i) the reduction of neckteeth production is dependent on the melatonin concentration and the most effective dose was not applied in the present test, and/or ii) a complete suppression of the neckteeth is not possible, as the chemical information about the presence of Chaoborus has higher priority.

In order to investigate whether melatonin generally attenuates stress responses or whether an effect can only be found in response to chemical cues released by predators, we exposed a D. pulex clone to a non-predator stressor. During most of the season Daphnia reproduce parthenogenetically by producing subitaneous eggs. These eggs develop immediately in the brood chamber, and neonates are released with the next maternal molt. Under stress conditions, Daphnia produce resting eggs (enclosed in an ephippium). A multitude of environmental factors and stressors have been identified to induce ephippia in Daphnia, e.g. photoperiod [31], low food quantity [31] and quality [18,32,33], chemical cues released by predators [34] and high population density (crowding) [31]. The cause for ephippia production in crowded D. pulex are infochemicals released by conspecifics [35].

Here, we used an obligate parthenogenetic D. pulex clone that produces resting eggs asexually (i.e. without males). This clone was kept under moderate crowding conditions. In the first brood, D. pulex showed a high production of ephippia and no difference between treatments. However, after the reduction of animal number and thus a decrease in the intensity of crowding, we found a lower production of ephippia in the second brood and a significant difference between treatments. Also here, the addition of melatonin led to an attenuation of stress response visible as a lower ephippia production in comparison to the melatonin-free control. Therefore, the addition of melatonin compensates for moderate stress, but cannot counteract strong stress. Either the added concentration of melatonin was too low to decrease responses to overcrowding, or melatonin in general has no influence if a stress signal surpasses a particular threshold level. Interestingly, the number of live neonates also increased in the treatment with melatonin. The difference in neonate production in the first clutch was due to the fact that a very few neonates were observed, and those in only two replicates of the control treatment, whereas some neonates were found in all replicates of the melatonin treatment. Although a significant difference in neonate number in the first clutch was observed, no significant difference in ephippia production in the first brood was found. However, a direct link between the number of neonates and (energy) investment into resting eggs appears in the third clutch; the significantly higher number of ephippia produced clearly corresponds with a lower number of neonates in the control treatment, and vice versa in the melatonin treatment. This indicates that after producing the second ephippial brood, maternal reserves were too exhausted to provide sufficient resources for many subitaneous neonates in a third clutch.

The stressors ‘predation’ and ‘crowding’ are mediated by chemical signals/cues, either from predators or conspecifics. One possibility is that melatonin applied to the medium acts as an external, artificial suppressor of stress signals, i.e. melatonin does not act within a daphnid’s body, but rather disturbs chemical communication in the ambient environment. Another possibility is that melatonin is taken up into the Daphnia’s body, in which case the attenuation of stress responses observed here should be accompanied by changes at the molecular level. This would be an interesting topic for future studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we could not confirm that melatonin increases the longevity of Daphnia. Neither female nor male Daphnia were affected by melatonin. Therefore, a general positive effect of melatonin on longevity of all invertebrates as suggested by [24] could here not be explicitly confirmed for the aquatic invertebrate Daphnia. Reiter et al. [24] stated that the role of melatonin in extending normal longevity, especially in mammals, is still in question. Therefore, we subscribe to the view of Anisimov et al. [36], i.e. that caution should be exercised before melatonin is recommended for long-term administration as a geroprotector.

On the other hand we were able to show that melatonin clearly attenuated Daphnia’s stress responses under acute stress conditions. Our results supports the idea that melatonin disturbs predator-avoidance behavior of Daphnia [17], since we demonstrated that melatonin attenuates i) morphological predator-defense responses induced by an invertebrate kairomone, and ii) influences life-history characteristics transmitted via chemical cues from conspecifics.

Animal ethics statement

We herewith confirm that the invertebrates used here are not under regulation. All experiments comply with institutional, national, and international guidelines.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eric von Elert for the provision of the climate chambers. Thanks to Jens Schröder for help in conducting the experiments. The authors would also like to thank Frederic Bartlett for English corrections. AW thanks the German Research Foundation (DFG) for funding of his research (WA 2445/8-1).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AS designed and performed all experiments. MC produced the Chaoborus extract and supported AS in scoring the neckteeth. AS und AW analyzed the data. AS wrote and AW and MC approved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Anke Schwarzenberger, Email: Anke.Schwarzenberger@gmx.de.

Mark Christjani, Email: M_Christjani@gmx.de.

Alexander Wacker, Email: Alexander.Wacker@uni-potsdam.de.

References

- 1.Lerner AB, Case JD, Takahashi Y, Lee TH, Mori W. Isolation of melatonin, the pineal gland factor that lightens melanocytes. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:2587. doi: 10.1021/ja01543a060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poeggeler B. Melatonin and the light–dark zeitgeber in vertebrates, invertebrates and unicellular organisms - Introduction. Experientia. 1993;49:611–613. doi: 10.1007/BF01923940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poeggeler B. Melatonin, aging, and age-related diseases - Perspectives for prevention, intervention, and therapy. Endocrine. 2005;27:201–212. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:27:2:201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonilla E, Medina-Leendertz S, Diaz S. Extension of life span and stress resistance of Drosophila melanogaster by long-term supplementation with melatonin. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:629–638. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00229-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Osuna C, Gitto E. Actions of melatonin in the reduction of oxidative stress - A review. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7:444–458. doi: 10.1007/BF02253360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harman D. Free-radical theory of aging. Mutat Res. 1992;275:257–266. doi: 10.1016/0921-8734(92)90030-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sainath S, Swetha C, Reddy P., Sr What do we (need to) know about the melatonin in crustaceans? J Exp Zool A Ecol Genet Physiol. 2013;319:365–377. doi: 10.1002/jez.1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tilden AR, Brauch R, Ball R, Janze AM, Ghaffari AH, Sweeney CT, Yurek JC, Cooper RL. Modulatory effects of melatonin on behavior, hemolymph metabolites, and neurotransmitter release in crayfish. Brain Res. 2003;992:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tilden AR, Rasmussen P, Awantang RM, Furlan S, Goldstein J, Palsgrove M, Sauer A. Melatonin cycle in the fiddler crab Uca pugilator and influence of melatonin on limb regeneration. J Pineal Res. 1997;23:142–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.1997.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sainath S, Reddy P., Sr Evidence for the involvement of selected biogenic amines (serotonin and melatonin) in the regulation of molting of the edible crab, Oziotelphusa senex senex Fabricius. Aquaculture. 2010;302:261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2010.02.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maciel FE, Ramos BP, Geihs MA, Vargas MA, Cruz BP, Meyer-Rochow VB, Vakkuri O, Allodi S, Monserrat JM, Maia Nery LE. Effects of melatonin in connection with the antioxidant defense system in the gills of the estuarine crab Neohelice granulata. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2010;165:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Markowska M, Bentkowski P, Kloc M, Pijanowska J. Presence of melatonin in Daphnia magna. J Pineal Res. 2009;46:242–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebert D. A genome for the environment. Science. 2011;331:539–540. doi: 10.1126/science.1202092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foulkes NS, Borjigin J, Snyder SH, SassoneCorsi P. Rhythmic transcription: the molecular basis of circadian melatonin synthesis. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:487–492. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaas B, Krishnarao K, Marion E, Stuckey L, Kohn R. Impulse: The Premier Journal for Undergraduate Publications in the Neurosciences. 2009. Effects of melatonin and ethanol on the heart rate of Daphnia magna. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashian DR, Dodson SI. Effects of vertebrate hormones on development and sex determination in Daphnia magna. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2004;23:1282–1288. doi: 10.1897/03-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bentkowski P, Markowska M, Pijanowska J. Role of melatonin in the control of depth distribution of Daphnia magna. Hydrobiologia. 2010;643:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s10750-010-0134-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch U, Von Elert E, Straile D. Food quality triggers the reproductive mode in the cyclical parthenogen Daphnia (Cladocera) Oecologia. 2009;159:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s00442-008-1216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Meester L, Vandenberghe J, Desender K, Dumont HJ. Genotype-dependent daytime vertical-distribution of Daphnia magna in a shallow pond. Belg J Zool. 1994;124:3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Elert E, Jüttner F. Phosphorus limitation not light controls the exudation of allelopathic compounds by Trichormus doliolum. Limnol Oceanogr. 1997;42:1796–1802. doi: 10.4319/lo.1997.42.8.1796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Threlkeld ST. Estimating cladoceran birth-rates - Importance of egg mortality and the egg age distribution. Limnol Oceanogr. 1979;24:601–612. doi: 10.4319/lo.1979.24.4.0601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tollrian R. Neckteeth formation in Daphnia pulex as an example of continuous phenotypic plasticity: Morphological effects of Chaoborus kairomone concentration and their quantification. J Plankton Res. 1993;15:1309–1318. doi: 10.1093/plankt/15.11.1309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crawley MJ. Statistical Computing: An Introduction to Data Analysis Using S-Plus. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Mayo JC, Sainz RM, Lopez-Burillo S. Melatonin, longevity and health in the aged: an assessment. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:1323–1329. doi: 10.1080/1071576021000038504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietrzak B, Bednarska A, Grzesiuk M. Longevity of Daphnia magna males and females. Hydrobiologia. 2010;643:71–75. doi: 10.1007/s10750-010-0138-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Izmaylov DM, Obukhova LK. Geroprotector effectiveness of melatonin: investigation of lifespan of Drosophila melanogaster. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;106:233–240. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(98)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lass S, Spaak P. Chemically induced anti-predator defences in plankton: a review. Hydrobiologia. 2003;491:221–239. doi: 10.1023/A:1024487804497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson P, Dodson SI. Invited review: chemical communication in planktonic animals. Arch Hydrobiol. 1993;129:129–155. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havel JE, Dodson SI. Chaoborus predation on typical and spined morphs of Daphnia Pulex - Behavioral observations. Limnol Oceanogr. 1984;29:487–494. doi: 10.4319/lo.1984.29.3.0487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riessen HP, Trevett-Smith JB. Turning inducible defenses on and off: adaptive responses of Daphnia to a gape-limited predator. Ecology. 2009;90:3455–3469. doi: 10.1890/08-1652.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvalho GR, Hughes RN. The effect of food availability, female culture-density and photoperiod on ephippia production in Daphnia magna Straus (Crustacea, Cladocera) Freshwat Biol. 1983;13:37–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1983.tb00655.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrusan G, Fink P, Lampert W. Biochemical limitation of resting egg production in Daphnia. Limnol Oceanogr. 2007;52:1724-U1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fink P, Pflitsch C, Marin K: Dietary essential amino acids affect the reproduction of the keystone herbivoreDaphnia pulex.PLoS ONE 2011, 6: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Slusarczyk M. Predator-induced diapause in Daphnia. Ecology. 1995;76:1008–1013. doi: 10.2307/1939364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lürling M, Roozen F, Van Donk E, Goser B. Response of Daphnia to substances released from crowded congeners and conspecifics. J Plankton Res. 2003;25:967–978. doi: 10.1093/plankt/25.8.967. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anisimov VN, Zavarzina NI, Zabezhinskii MA, Popovich IG, Anikin IV, Zimina OA, Solov’ev MV, Shtylik AV, Arutiunian AV, Oparina TI, Prokopenko VM, Khavinson VK. The effect of melatonin on the indices of biological age, on longevity and on the development of spontaneous tumors in mice. Vopr Onkol. 2000;46:311–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]