Obesity, defined as body mass index (BMI) greater than 30, is an increasingly serious problem, precipitating numerous health conditions and taking a staggering toll on health care resources. (Anderson, Wiener, Khatutsky, & Armour, 2013) Reports indicate a dramatic increase in obesity in the United States since 1980 with more than one-third of U.S. adults (35.7%) and approximately 17% (or 12.5 million) of children and adolescents aged 2—19 years reported to be obese. (CDC, 2013a, 2013b) The increased prevalence of obesity between 1998 and 2006 is reported to be responsible for almost $40 billion of increased medical spending, including $7 billion in Medicare prescription drug costs. (Finkelstein, Trogdon, Cohen, & Dietz, 2009) Obesity results in substantial additional health care expenditures for people with disabilities. (Anderson et al., 2013)

Most conditions resulting from obesity contribute to greater risks for obese individuals to require access to rehabilitation nurses. Obesity is related to increased incidence of a many conditions, including diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, musculoskeletal conditions, nonalcoholic liver disease, cancer and all causes of mortality, (Flegal, Kit, Orpana, & Graubard, 2013; Ogden, Yanovski, Carroll, & Flegal, 2007) even when adjusted for smoking, clinical conditions, and age. (Flegal, Kit, & Graubard, 2013) Obese passengers are more likely to suffer a more severe head trauma after a frontal collision. (Tagliaferri, Compagnone, Yoganandan, & Gennarelli, 2009) Trauma victims in general who are obese have poorer outcomes; and all obese individuals have greater risk for comorbidities with unique implications for rehabilitation nursing care. (Capodaglio et al., 2013; VanHoy & Laidlow, 2009) The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between obesity and traumatic brain injury (TBI) when adjusting for related variables in a high risk female population.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Because obesity has been associated with TBI for centuries, (Ashrafian, 2012) it is important to evaluate this association in order to better understand how to design interventions to prevent or limit long term consequences. TBI survivors may suffer from comorbidities related to obesity and restricted participation in life activities and healthy lifestyle. Obesity is known to be prevented with diet and exercise. Yet, proper diet and exercise could be particularly problematic for survivors of TBI due to cognitive and physical limitations. Though weight gain in children during the first year after TBI was significant, (Jourdan et al., 2012) little is understood about obesity in long term survivors of TBI in relation to other variables.

Other Physical and Emotional Trauma

Obesity in adults has also been related to various other forms of emotional and physical trauma including childhood physical abuse (CPA), childhood sexual abuse (CSA), and other early life traumatic experiences. (Bentley & Widom, 2009; Felitti, 1991, 1993; Williamson, Thompson, Anda, Dietz, & Felitti, 2002) Yet studies suggest the need to identify specific contexts of these relationships. Acute or chronic physical or emotional stress may lead to or exacerbate several conditions including obesity, and the metabolic syndrome. For example, behaviors such as unhealthy lifestyles and neuroendocrine stress mechanisms promote obesity and metabolic abnormalities, dysregulation of the stress system, and increased secretion of cortisol, catecholamines, and interleukin-6, with concurrently elevated insulin concentrations, contributing to development of central obesity, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. (Pervanidou & Chrousos, 2012)

Though neurobiology of food intake is complex and further study is needed, brain regions and neurotransmitter pathways that have been implicated could be affected by TBI or other traumatic events. (Berthoud, 2012; Smeets, Charbonnier, van Meer, van der Laan, & Spetter, 2012) Compensatory behaviors including over-eating and smoking could provide immediate partial relief from emotional problems caused by various traumatic childhood experiences in the lives of females. (Felitti, 2009; Fuller-Thomson, Filippelli, & Lue-Crisostomo, 2013) Because prescribed and self-medication of various forms are used to treat emotional and physical pain and depression associated with previous trauma, it is also important to evaluate childhood physical and sexual abuse, use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), depression, and cigarette smoking along with TBI for their relationships to obesity.

Furthermore, suicide attempts that have been related to childhood abuse, (Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2008) and obesity in females (Klinitzke, Steinig, Blüher, Kersting, & Wagner, 2013) are prevalent in the histories of female prison inmates (Brewer-Smyth, Burgess, & Shults, 2004). Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate hypothesized relationships between obesity, TBI, suicide attempts, CPA, CSA, depression, cigarette smoking, SSRIs, age, in a high risk female population.

Theoretical Framework

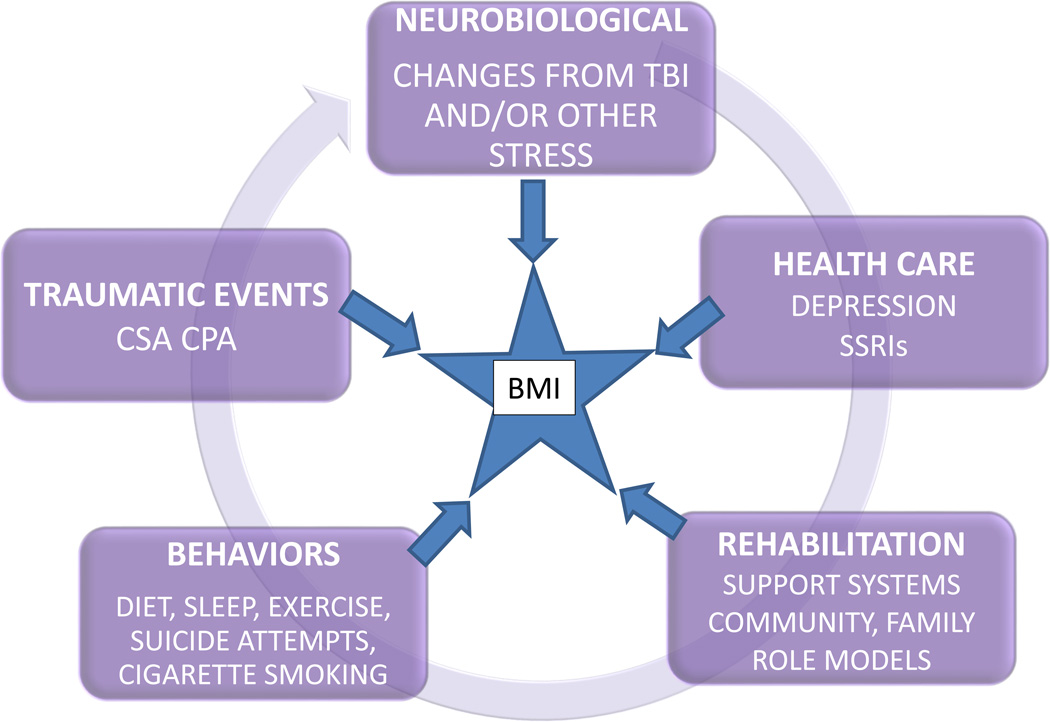

This study was built upon a convergence of theories suggesting that BMI results from a cycle of events, such as emotional and physical trauma that lead to neurobiological outcomes that could be influenced by health care resources and related behaviors contributing to recovery or to further physiological decline (Figure 1). The Developmental Traumatology Model describes complex psychiatric, psychobiological, and behavioral outcomes resulting from the impact of adversity on the developing child including biological stress systems and adverse brain development after childhood abuse. (De Bellis, 2001; De Bellis, Spratt, & Hooper, 2011) Social Learning Theory is a perspective stating that people learn within a social context, facilitated through concepts such as modeling and observational learning. (Bandura, 1977, 1978) Furthermore, a cycle of increasing neurological decline after traumatic life events, contributing to low self-esteem and subsequent increases in high risk behaviors has also been reported. (Brewer-Smyth, 2001; Brewer-Smyth et al., 2007)

Figure 1.

Theory of the Cycle of Events Contributing to Obesity

Taken together, these studies suggest that either physical or emotional traumatic events could result in physiological, psychobiological, emotional, and/or behavioral outcomes that could contribute to conditions such as obesity. Obesity could result from physiological outcomes of trauma such as neurological, neuroendocrine, or other metabolic changes after TBI or other physical or emotional traumatic events. Furthermore, abuse during childhood could lead to learned behaviors by the survivor that might suggest poor self-esteem and lack of regard for self, such as poor diet, over eating, and inadequate exercise.

Methods

Design

This study was a secondary analysis of data from previously reported cross sectional studies of female prison inmates. These data sets were selected because of the unfortunately high rates of obesity, histories of TBI, childhood abuse, and violence against self and others including suicide attempts in this population. Methods are described elsewhere. (Brewer-Smyth, 2004; Brewer-Smyth et al., 2007; Brewer-Smyth & Burgess, 2008; Brewer-Smyth et al., 2004) Briefly, all participants were evaluated during private interviews to assess their history, physical examination, and all related measurements described below. Self-reported information was compared with medical, criminal, and other documentation; all of which were conducted by this investigator.

Institutional Review Boards of the principal investigator’s universities approved the studies. The Office of Health Research Protection verified that the study complied with federal regulations regarding prisoner research and issued a certificate of confidentiality. (Brewer-Smyth, 2008)

Sampling Methodology

Statistical power analysis was based on the design, methods, and number of variables in the original study. (Brewer-Smyth et al., 2004) No statistical adjustments were made for missing data. Therefore, all participants with missing data were eliminated from this study. Interpretation of the statistical results of this secondary analysis is further described below.

This study included a random sample of 81 female inmates from the general female prison population. Inclusion criteria required participants to speak and understand English, pass a quiz demonstrating understanding of the informed consent indicating that they were not severely neurologically impaired, or using steroid hormones due to neuroendocrine measures of previous studies. Length of time since initially being incarcerated could influence stress levels that impact the neuroendocrine system as well as BMI. Therefore, participants were excluded until they had been convicted, sentenced, and incarcerated in that same prison for a minimum of 2 months.

Measurements

BMI

BMI was calculated based on height and weight of each participant. Though all received the same prison diet, there were very few restrictions on obtaining additional food.

TBI

All history and physical examinations focusing on neuropsychological abnormalities were conducted by this investigator using techniques that were validated by 2 neurologists. (Brewer-Smyth et al., 2007) Participant’s TBI reports were validated by records when available and physical examinations of neurological deficits consistent with the injury described by the participant, palpable skull injuries, and scars.

CPA and CSA

Childhood physical and sexual abuse before age 18 was measured with Muenzenmaier’s scale. (Brewer-Smyth et al., 2004; Meyer, Muenzenmaier, Cancienne, & Struening, 1996; Muenzenmaier, Meyer, Struening, & Ferber, 1993) Validity and reliability has been reported in tests of women of similar age, ethnic background, and education, including mentally ill women. (Meyer et al., 1996; Muenzenmaier et al., 1993) Abuse scores were validated by records, scars, and other evidence of physical and emotional trauma.

Depression

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) was used to measure depression at the time of interview. Validity and reliability has been reported extensively with both psychiatric and non-psychiatric populations. Participants were instructed to describe the way they have been feeling during the past two weeks.

Suicide attempts

Suicide attempts were determined by participant reports verified by related evidence of physical and emotional trauma and records when available.

SSRIs

SSRI use was determined by prison medication administration records.

Cigarette smoking

Smoking was determined by participant reports and observations.

Age

Age was determined by participant report and record review.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with IBM SPSS statistics 20. Descriptive statistics were computed for comparisons between obese and non-obese females with frequencies, (table 1) graphical checks (Figures 2–4) and bivariate analysis. Multivariable logistic regression models were developed to estimate relationships between obesity and hypothesized related variables.

Table 1.

| Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Obese | No | 46 |

| Yes | 35 | |

| TBI | No | 41 |

| Yes | 40 | |

| Suicide Attempts | No | 52 |

| Yes | 29 | |

| Current Smoker | No | 15 |

| Yes | 66 | |

| On SSRIs | No | 52 |

| Yes | 29 | |

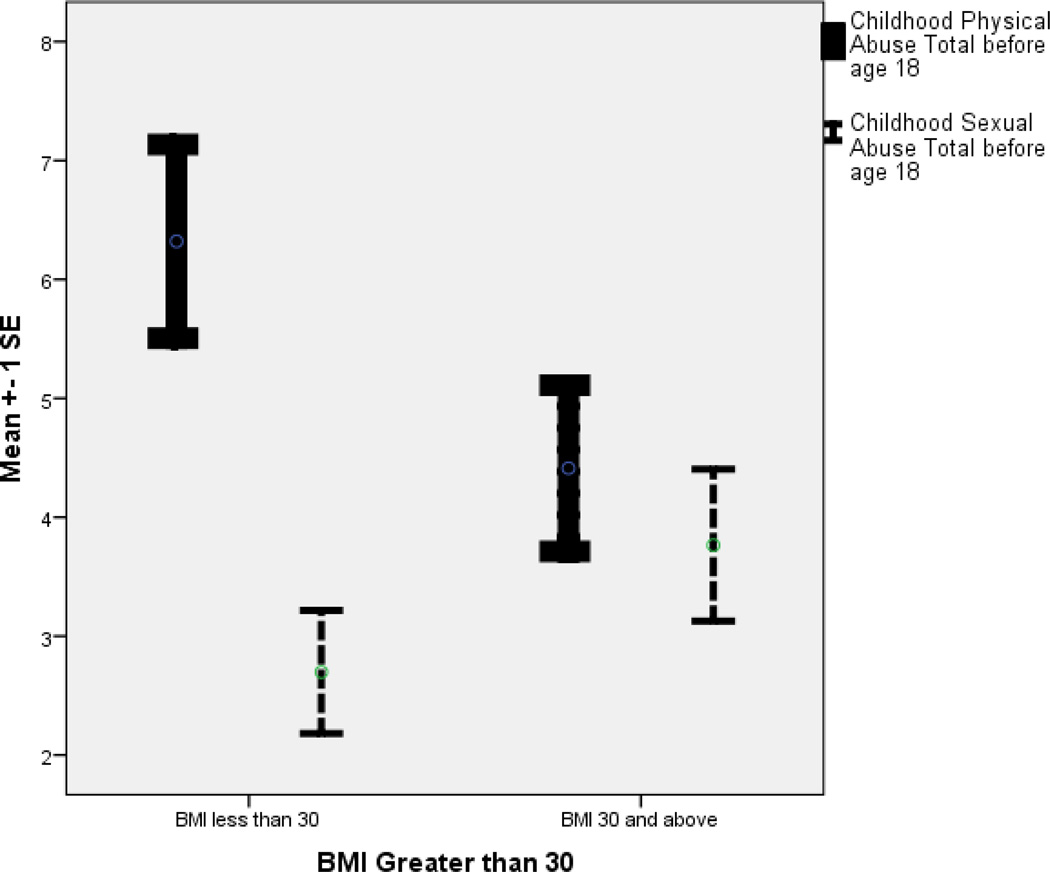

Figure 2.

Childhood Abuse and BMI

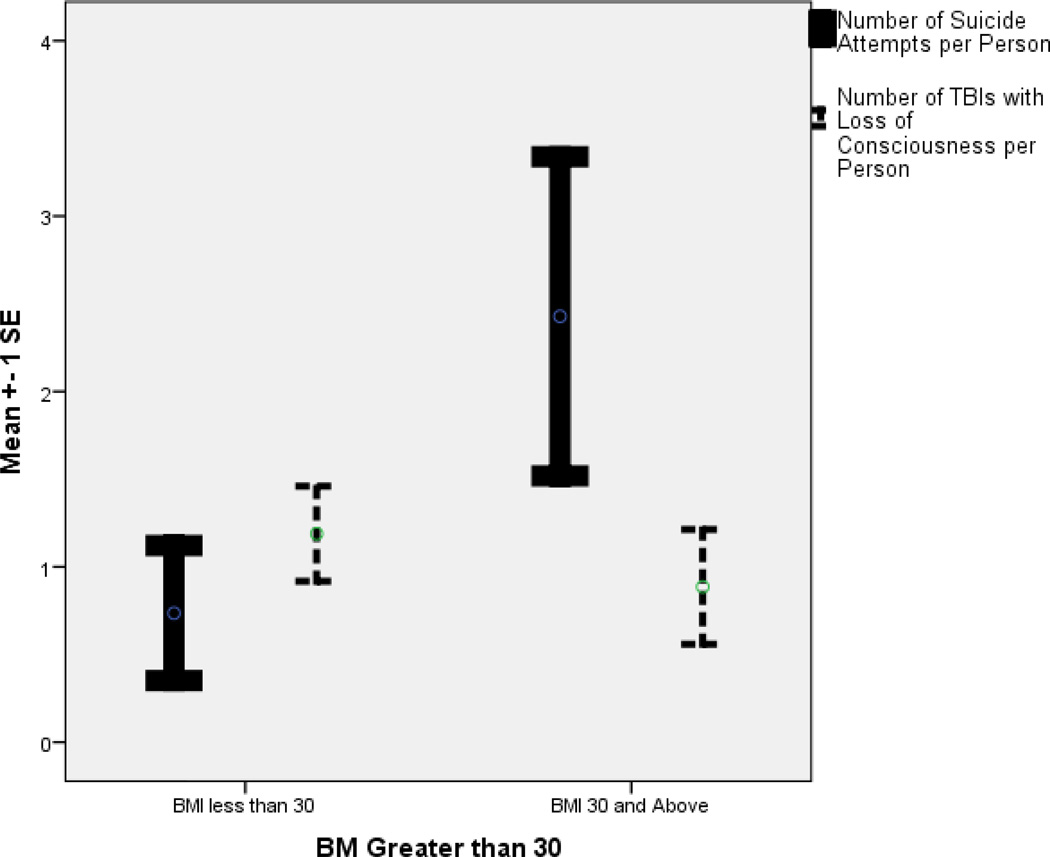

Figure 4.

BMI, Number of TBIs per Person, Number of Suicide Attempts per Person

Variables identified as potential correlates of obesity based on bivariate analyses and literature review, such as CSA, cigarette smoking, and depression, were then used to obtain a final multivariable logistic regression model with “obesity” as the outcome. Backwards, stepwise elimination resulted in a multivariate model with the fewest covariates and best model fit while adjusting for depression, age, on SSRIs, and cigarette smoking. The final model was assessed with graphical checks and goodness of fit.

Findings

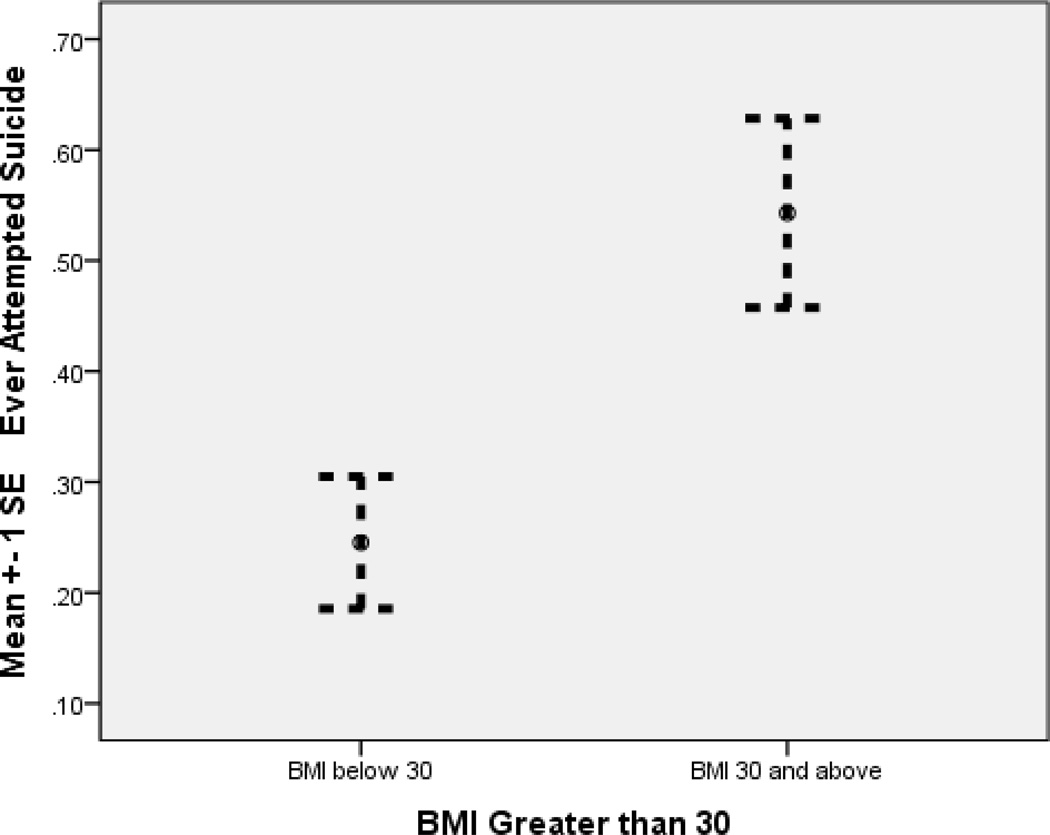

Obesity was noted in 35 of the 81 participants, and 40 of the 81 had at least 1 TBI prior to participation in this study. Obesity was related to history of a decreased number of TBIs per person (OR=.678; 95% CI .477-.964), increased CSA scores (OR=1.209; 95% CI 1.019–1.435), suicide attempts (OR=14.246; 95% CI 3.139–64.651), and decreased CPA (OR=.879; 95% CI.775–.997), adjusting for current smoking (OR=.218; 95% CI .046–1.034), BDI II depression scores (OR=1.009; 95% CI .944–1.078), currently using SSRIs (OR=.263; 95% CI .058–1.191), and age (OR=1.022; 95% CI .951–1.099). Logistic regression model (Table 2) explained 43% of the variance. Hosmer and Lemeshow test was not significant (X2 = 3.744, p = .879) indicating that the model was a good fit.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression comparing those with BMI greater than 30 to those less than 30

| Unadjusted Estimates | §Adjusted Estimates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sig. | Odds Ratio |

95% C.I. | Sig. | Odds Ratio |

95% C.I. | |||

| Ever Attempted Suicide | .006 | 3.562 | 1.428 | 8.890 | .001 | 14.246 | 3.139 | 64.651 |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | .227 | 1.074 | .957 | 1.206 | .029 | 1.209 | 1.019 | 1.435 |

| Number of TBIs per Person | .452 | .911 | .714 | 1.162 | .030 | .678 | .477 | .964 |

| Childhood Physical Abuse | .102 | .929 | .851 | 1.015 | .045 | .879 | .775 | .997 |

| Cigarette Smoking | .047 | .320 | .104 | .988 | .055 | .218 | .046 | 1.034 |

| On SSRIs | .417 | .680 | .267 | 1.728 | .083 | .263 | .058 | 1.191 |

| Depression | .391 | .982 | .941 | 1.024 | .800 | 1.009 | .944 | 1.078 |

| Age | .122 | 1.040 | .990 | 1.092 | .548 | 1.022 | .951 | 1.099 |

Comprises final multivariate model

Though a p value of .05 is the common measure to determine significance, it could be argued that this should be adjusted with secondary analysis based on number of variables. Therefore, a p value of .01 is a more conservative indicator of significance for this study. Subsequently, having attempted suicide is the statistically significant variable.

Discussion

BMI greater than 30 at the time of interview was related to history of a decreased number of TBIs per person, greater frequency and severity of CSA, greater number of suicide attempts per person, and decreased frequency and severity of childhood physical abuse, adjusting for current smoking, depression, currently using SSRIs, and age. However, because the power analysis was based on design and methods of original studies, findings must be interpreted with caution due to limited power. Yet, this study does provide critical information upon which to base further scholarly inquiry.

Because this model explained 42% of the variance, there are other factors contributing to why one might be obese that have not been measured here. They might include numerous variables such as hormonal, metabolic, environmental, and life-style behaviors; all of which could be related to BMI of patients in rehabilitation.

These findings are consistent with reports of others who documented obesity related to previous maltreatment (Hollingsworth, Callaway, Duhig, Matheson, & Scott, 2012; Shin & Miller, 2012) and suicide attempts. (Klinitzke et al., 2013) However, this study provides new information regarding TBI and obesity when adjusting for these related variables.

Strengths and Limitations

Though one might suspect that prison inmates are not reliable sources of information, studies indicate congruence between prisoner self-reports and other records. (Brewer-Smyth et al., 2004; Schofield, Butler, Hollis, & D'Este, 2011) Reporting false information for secondary gain was limited or eliminated based on federally required informed consent for studying prison inmates and certificates of confidentiality. (Brewer-Smyth, 2008) For example, informed consents must clearly include in advance that participation in research has no effect on parole. A confidentiality certificate issued by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) protected identifiable research information from forced disclosure. Prisons can be reliable settings for research because many variables are controlled by the system. Furthermore, childhood abuse self-reports have been reported to be reliable in longitudinal studies. (Pereira da Silva & da Costa Maia, 2013)

Causation cannot be determined by this retrospective cross sectional study. Initial studies are preferable to secondary analysis. However, this design is less costly and time consuming than longitudinal studies, and randomizing into conditions of this study cannot be considered for clinical trials. Critical information is gained from these findings to inform future inquiry.

Clinical Relevance

Obesity is a serious, complex problem that will not be alleviated by teaching patients about diet and exercise, as most people know they should not smoke, abuse alcohol or other substances, over eat, or live a sedentary lifestyle. Yet the population in general does not do what they know they should do. Though every effort must be made to assist patients in understanding how to limit obesity with all available resources, (CDC, 2013c) nurses also need to understand that obesity may be the result of dietary self-medication of painful previous experiences including childhood physical and emotional trauma.

Obese individuals are accessing health care including acute and long-term rehabilitation at increasing rates. Rehabilitation nursing involves much more than bowel, bladder, and physical mobility. Rehabilitation nurses are in a critical position to help stop the revolving door for patients with comorbidities associated with obesity that could require frequent re-admissions.

Obese females who access rehabilitation facilities for any reason, especially due to injuries that occur during suicide attempts, need to be evaluated for other underlying etiologies such as previous physical and emotional trauma including childhood sexual abuse. Experiencing child abuse has been associated with an increased risk of poor physical health outcomes in adulthood including neurological, musculoskeletal, respiratory, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders; (Wegman & Stetler, 2009) all of which could increase the likelihood of child abuse survivors requiring rehabilitation resources.

Obesity is a particularly critical problem for females who had attempted suicide that was frequently reported to have been committed because of poor self-esteem and lack of regard for self after having been a victim of abuse. Because the vast majority of suicide attempts committed by these adult females had occurred during their teen years after having been a victim of childhood abuse, these findings are particularly applicable for pediatric nurses. Some participants reported that they denied having been abused when asked by health care workers at the time of their injury because they either feared the abuser and/or the abuser was perceived to be their only source of financial support. Some denied having been abused when asked by this investigator, then reported otherwise in response to abuse scale questions; suggesting that they had grown accustomed to abusive behaviors that they perceived to be normal. Building a trusting relationship is critical to obtaining self-reports of abuse.

Nurses need to be aware of their state laws and resources available within their state; while being vigilant in identifying signs and symptoms of abuse and self-harm. Overviews of suicide prevention in youth populations have been reported. (Amitai & Apter, 2012; Cooper, Clements, & Holt, 2011) Yet, further research is needed to evaluate and compare the effectiveness of interventions.

Rehabilitation nursing should begin in critical care settings, progress to acute rehabilitation settings, and continue into longer-term rehabilitation and community follow-up. Yet funding and other barriers may prevent patient access to rehabilitation nurses. Though TBI and other neurological abnormalities were prevalent in 95% of this female prison population, the vast majority had never been in a rehabilitation setting, nor had they ever seen a rehabilitation nurse. Unfortunately, as mental health facilities that once housed individuals with long term neurological and other mental health conditions have closed, prison systems seem to be the main alternative for those in need of some form of neurological rehabilitation. Rehabilitation nurses need to measure and document the critical impact of our skills in order to justify associated costs and decrease the major public health implications of the epidemic of incarceration. (Dumont, Brockmann, Dickman, Alexander, & Rich, 2012)

In conclusion, CSA is a serious problem that can precipitate suicide attempts, obesity, and subsequent co-morbidities requiring rehabilitation. Laws and procedures for reporting child abuse vary from state to state. Failure to report child abuse could result in large fines in some states such as Delaware. Rehabilitation nurses are uniquely positioned to play a critical role in decreasing associated staggering public health care costs by assessing and addressing potential underlying etiologies, making referrals when needed, and reporting abuse to proper authorities.

Figure 3.

BMI and Suicide Attempts

Acknowledgement

Data collection for this study was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health 20RR016472-04, T32 NR07036, Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society, Rehabilitation Nursing Foundation, The Baxter Foundation, University of Delaware General University Research Fund, and University of Delaware Research Foundation. Barry Milcarek is also acknowledged posthumously for his statistical assistance.

References

- Amitai M, Apter A. Social aspects of suicidal behavior and prevention in early life: a review. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2012;9(3):985–994. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9030985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WL, Wiener JM, Khatutsky G, Armour BS. Obesity and people with disabilities: The implications for health care expenditures. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013 doi: 10.1002/oby.20531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafian H. Henry VIII's obesity following traumatic brain injury. Endocrine International Journal of Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. 2012;42:218–219. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9581-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Oxford, England: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social learning theory of aggression. The Journal of communication. 1978;28(3):12–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1978.tb01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual-Second Edition. 2nd ed. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley T, Widom CS. A 30-year follow-up of the effects of child abuse and neglect on obesity in adulthood. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2009;17(10):1900–1905. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoud H-R. The neurobiology of food intake in an obesogenic environment. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2012;71(4):478–487. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Smyth K. 3003603 Ph.D. Ann Arbor: University of Pennsylvania; 2001. Neurologic and neuroendocrine correlates of violent criminal behavior of female inmates. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/251047178?accountid=10457 ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I database. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Smyth K. Neurorehabilitation nursing research behind bars: the lived experience. Rehabilitation nursing : the official journal of the Association of Rehabilitation Nurses. 2004;29(3):75–76. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2004.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Smyth K. Ethical, regulatory, and investigator considerations in prison research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2008;31(2):119–127. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000319562.84007.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Smyth K, Bucurescu G, Shults J, Metzger D, Sacktor N, van Gorp W, Kolson D. Neurological function and HIV risk behaviors of female prison inmates. The Journal of neuroscience nursing : journal of the American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. 2007;39(6):361–372. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200712000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Smyth K, Burgess AW. Childhood sexual abuse by a family member, salivary cortisol, and homicidal behavior of female prison inmates. Nursing research. 2008;57(3):166–174. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000319501.97864.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer-Smyth K, Burgess AW, Shults J. Physical and sexual abuse, salivary cortisol, and neurologic correlates of violent criminal behavior in female prison inmates. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capodaglio P, Lafortuna C, Petroni ML, Salvadori A, Gondoni L, Castelnuovo G, Brunani A. Rationale for hospital-based rehabilitation in obesity with comorbidities. European journal of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2013;49(3):399–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Data and Statistics Facts. [Retrieved July 6,, 2013];Overweight and Obesity. 2013a Apr 27; 2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/facts.html.

- CDC. Diabetes and Obesity Statistics and Trends. [Retrieved July 6, 2013];Overweight and Obesity. 2013b Mar; 2013 from www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/slides/maps_diabetesobesity_trends.pptx.

- CDC. Healthy Weight - it's not a diet, it's a lifestyle! [Retrieved July 20, 2013];Healthy Weight. 2013c Aug 17; 2011 from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/index.html.

- Cooper GD, Clements PT, Holt K. A review and application of suicide prevention programs in high school settings. Issues in mental health nursing. 2011;32(11):696–702. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.597911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD. Developmental traumatology: the psychobiological development of maltreated children and its implications for research, treatment, and policy. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(3):539–564. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Spratt EG, Hooper SR. Neurodevelopmental biology associated with childhood sexual abuse. J Child Sex Abus. 2011;20(5):548–587. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2011.607753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont DM, Brockmann B, Dickman S, Alexander N, Rich JD. Public health and the epidemic of incarceration. Annual review of public health. 2012;33:325–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ. Long-term medical consequences of incest, rape, and molestation. Southern medical journal. 1991;84(3):328–331. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ. Childhood sexual abuse, depression, and family dysfunction in adult obese patients: a case control study. Southern Medical Journal. 1993;86(7):732–736. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9(3):131–132. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2008;32(6):607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(5):w822–w831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Kit BK, Graubard BI. Overweight, obesity, and all-cause mortality—reply. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1681–1682. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Kit BK, Orpana H, Graubard BI. Association of all-cause mortality with overweight and obesity using standard body mass index categories: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2013;309(1):71–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.113905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Filippelli J, Lue-Crisostomo CA. Gender-specific association between childhood adversities and smoking in adulthood: findings from a population-based study. Public health. 2013;127(5):449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth K, Callaway L, Duhig M, Matheson S, Scott J. The Association between Maltreatment in Childhood and Pre-Pregnancy Obesity in Women Attending an Antenatal Clinic in Australia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e51868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan C, Brugel D, Hubeaux K, Toure H, Laurent-Vannier A, Chevignard M. Weight gain after childhood traumatic brain injury: a matter of concern. Developmental medicine and child neurology. 2012;54(7):624–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinitzke G, Steinig J, Blüher M, Kersting A, Wagner B. Obesity and suicide risk in adults--a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders. 2013;145(3):277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Muenzenmaier K, Cancienne J, Struening E. Reliability and validity of a measure of sexual and physical abuse histories among women with serious mental illness. Child abuse & neglect. 1996;20(3):213–219. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muenzenmaier K, Meyer I, Struening E, Ferber J. Childhood abuse and neglect among women outpatients with chronic mental illness. Hospital & community psychiatry. 1993;44(7):666–670. doi: 10.1176/ps.44.7.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The Epidemiology of Obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2087–2102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira da Silva SS, da Costa Maia A. The stability of self-reported adverse experiences in childhood: a longitudinal study on obesity. Journal of interpersonal violence. 2013;28(10):1989–2004. doi: 10.1177/0886260512471077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervanidou P, Chrousos GP. Metabolic consequences of stress during childhood and adolescence. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2012;61(5):611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield P, Butler T, Hollis S, D'Este C. Are prisoners reliable survey respondents? A validation of self-reported traumatic brain injury (TBI) against hospital medical records. Brain Inj. 2011;25(1):74–82. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.531690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SH, Miller DP. A longitudinal examination of childhood maltreatment and adolescent obesity: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) Study. Child abuse & neglect. 2012;36(2):84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets PAM, Charbonnier L, van Meer F, van der Laan LN, Spetter MS. Food-induced brain responses and eating behaviour. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2012;71(04):511–520. doi: 10.1017/S0029665112000808. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferri F, Compagnone C, Yoganandan N, Gennarelli TA. Traumatic brain injury after frontal crashes: relationship with body mass index. The Journal of trauma. 2009;66(3):727–729. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815edefd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanHoy SN, Laidlow VT. Trauma in obese patients: implications for nursing practice. Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 2009;21(3):377–389. vi–vii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegman HL, Stetler C. A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood. Psychosomatic medicine. 2009;71(8):805–812. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DF, Thompson TJ, Anda RF, Dietz WH, Felitti V. Body weight and obesity in adults and self-reported abuse in childhood. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002;26(8):1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]