Abstract

Although many studies have looked at the effects of different listening conditions on the intelligibility of speech, their analyses have often concentrated on changes to a single value on the psychometric function, namely, the threshold. Far less commonly has the slope of the psychometric function, that is, the rate at which intelligibility changes with level, been considered. The slope of the function is crucial because it is the slope, rather than the threshold, that determines the improvement in intelligibility caused by any given improvement in signal-to-noise ratio by, for instance, a hearing aid. The aim of the current study was to systematically survey and reanalyze the psychometric function data available in the literature in an attempt to quantify the range of slope changes across studies and to identify listening conditions that affect the slope of the psychometric function. The data for 885 individual psychometric functions, taken from 139 different studies, were fitted with a common logistic equation from which the slope was calculated. Large variations in slope across studies were found, with slope values ranging from as shallow as 1% per dB to as steep as 44% per dB (median = 6.6% per dB), suggesting that the perceptual benefit offered by an improvement in signal-to-noise ratio depends greatly on listening environment. The type and number of maskers used were found to be major factors on the value of the slope of the psychometric function while other minor effects of target predictability, target corpus, and target/masker similarity were also found.

Keywords: speech-in-noise understanding, psychometric functions, perceptual benefit

Introduction

A psychometric function describes the relationship between an observer's performance on a psychophysical task and some physical aspects of the stimuli. In particular, the psychometric function for speech intelligibility in noise describes a listener's ability to identify speech as a function of its intensity. Often, the psychometric function is summarized by two key parameters: the threshold, being the stimulus level required to give a particular level of performance (e.g., 50% correct), and the slope, being the maximum rate at which performance increases with changes in the stimulus level. Many studies have demonstrated that thresholds for speech intelligibility in noise depend greatly on various aspects of the target speech (e.g., French & Steinberg, 1947), the interfering sound (e.g., Carhart, Tillman, & Greetis, 1969; Festen & Plomp, 1990; French & Steinberg, 1947; Miller, 1947), and the listener (e.g., Duquesnoy, 1983; Festen & Plomp, 1990; Peters, Moore, & Baer, 1998). The situations, however, that result in changes to the rate at which intelligibility improves with an increase in the level of speech have been much less extensively studied.

The slope is crucial, as it—not the threshold—determines the increase in perceptual benefit a listener is likely to gain from small changes in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), such as may be offered by a directional microphone on a hearing aid. A steep psychometric function indicates that a small increase in SNR would lead to a large increase in intelligibility; conversely, if the slope is relatively shallow, the same SNR improvement would lead to a smaller perceptual improvement. We demonstrate here how much the slope of the psychometric function varies across experiments.

There is a wealth of psychometric function data available in the literature on speech identification, as many studies have looked at the factors that can affect the intelligibility of speech. Most of the published analyses of these data, however, have focused on changes in threshold, with slope changes far less commonly calculated and reported. No systematic corpus of these data is available, despite its obvious importance for isolating and identifying the factors associated with changes in slopes. We therefore carried out a systematic survey of the literature on psychometric functions for speech intelligibility, reanalyzing the data using a standard method to enable a direct comparison of slope data across different studies.

Our aims were to (a) quantify how much the slope of the psychometric function varies across experimental designs and listening conditions, (b) identify listening conditions that affect the slope of the psychometric function, and (c) discuss how these trends in slope conform with previously proposed explanations for variations in the slope of the psychometric function for speech intelligibility.

Methods

A computerized literature search was undertaken to find studies that had measured the intelligibility of speech as a function of SNR. The first reports of common speech tests and the studies citing these speech tests were reviewed, as many of these studies include psychometric functions in different noise conditions. A search was also carried out for articles citing either Egan, Carterette, and Thwing (1954) or Brungart (2001a)—these two studies were singled out as they reported unusually shaped psychometric functions of masked speech. The reference list of Brungart's article was also reviewed for possible studies to include in the survey. Other miscellaneous studies containing psychometric functions that were found over the course of approximately three years, up to a cutoff date of February 2012,1 were also included.

The inclusion criteria were that studies needed to report at least one psychometric function for speech identification that was (a) measured as a function of SNR or some other unit of relative presentation level from which SNR could be calculated, (b) measured over at least three points, (c) presented clearly in graphical or tabular form, and (d) averaged over several listeners. Individual data were excluded because we found that these data tended to be harder to accurately measure (e.g., multiple overlaying psychometric functions). Although interlistener variability in slope would undoubtedly provide additional insight into the factors affecting slope, such an analysis of the data was outside the scope of the current study, which aims to identify broad trends in slope across different listening conditions. Micheyl, Xiao, and Oxenham (2012) provide an example of a detailed reanalysis of psychometric data that does explicitly take into account individual variability.

A total of 146 relevant studies were found, giving 1,133 individual psychometric functions for further analysis. The individual data points for each psychometric function were recorded. These values were either taken directly from the article if the psychometric functions were reported in tabular form or extracted using a custom-written MATLAB program if the psychometric functions were displayed graphically. These data points were then fitted with a logistic function:

| (1) |

where x is the SNR (decibels), P is the percentage of correctly identified items, and m and c are constants: c being the SNR at which P = 50% correct, and m is the slope of the function at x = c. The slope (in % per dB) of the function is equal to −25m. The best fitting values of m and c were found using the solver function of Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, 2011), which uses a nonlinear least squares method. A logistic function was selected, as it has been suggested to be a reasonable sigmoidal model for psychometric data (Wichmann & Hill, 2001) and has been commonly used to describe psychometric functions for speech intelligibility (e.g., Festen & Plomp, 1990; Pichora-Fuller, Schneider, & Daneman, 1995; Rhebergen & Versfeld, 2005; Wightman, Callahan, Lutfi, Kistler, & Oh, 2003).

For consistency across all studies, none of the logistic fits was corrected for either chance or maximum performance. The information required for these corrections was not always available, and it was considered preferable to follow a standard procedure for all cases rather than correcting only a subset of the data. It is possible that this lack of correction for chance and ceiling effects could have affected slope estimates (Dai & Micheyl, 2011). Cases for which the standardized psychometric function was an extremely poor fit were excluded, however, to limit the effects of such errors in slope estimates (see Overview section).

The values of slope and c were added to the database with coding information on the experimental design (see later). In 219 psychometric functions, all data points were either below P = 50% or above P = 50%. In these cases, m, which is defined at P = 50%, is an extrapolation of the data. As such, slopes calculated in this way are unlikely to be good representations of the true slope of the data, and so were excluded from further analysis.

Each psychometric function in the survey was subjected to detailed coding of the experimental design for (1) target speech corpus (see later), (2) masker type (subcategories of speech, modulated noise,2 or static noise), (3) number of maskers, (4) presentation of stimuli (subcategories of monaural, diotic, or dichotic), (5) spatial locations of target and masker, (6) target language, (7) target predictability (subcategories of high predictability from context or low predictability from context), (8) whether the target was primed before presentation, (9) any signal processing of target or masker (subcategories of vocoded, filtered, or added reverberation). If the masker was competing speech, then further coding was carried out: (1) masker language, (2) masker corpus, (3) gender of the masker talker relative to the target talker (subcategories of same gender, different gender, or same talker), (4) masker intelligibility (subcategories of intelligible or unintelligible), (5) masker uncertainty (subcategories of masker talker fixed from trial to trial or masker content fixed from trial to trial), (6) pitch shift between target and masker voices (subcategories of small if less than 3 semitones, medium if 4–7 semitones, or large if greater than 8 semitones). Finally, general information about the studies' participants was also coded: (1) age-group (subcategories of children, young adult, or older adult) and (2) hearing loss (subcategories of normal hearing, a reported hearing loss, or cochlear implant user).

The target and masker speech were coded by the type of speech corpora used (e.g., BKB, IEEE, CRM, and SPIN).3 If this information was not available, or if the speech corpus was uncommon, the speech corpus was coded under the categories of valid sentences, invalid sentences, words, digits, continuous speech, or short tokens. Valid sentences described any stimuli consisting of syntactically and semantically correct sentences (e.g., sentences read from a history text book); invalid sentences described any stimuli consisting of either syntactically incorrect sentences (“cat on sat the mat”) or semantically incorrect sentences (“the thorn can wake the kettle”); continuous speech described any speech stimuli longer than a single sentence; and short tokens described smaller speech units such as syllables and phonemes.

Results

Overview

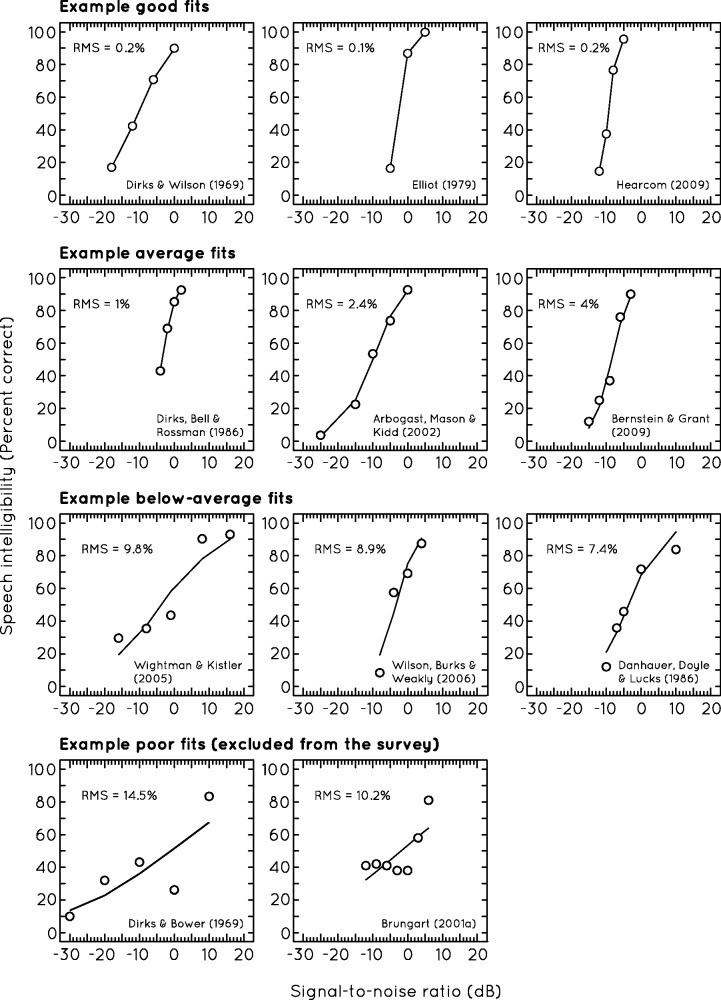

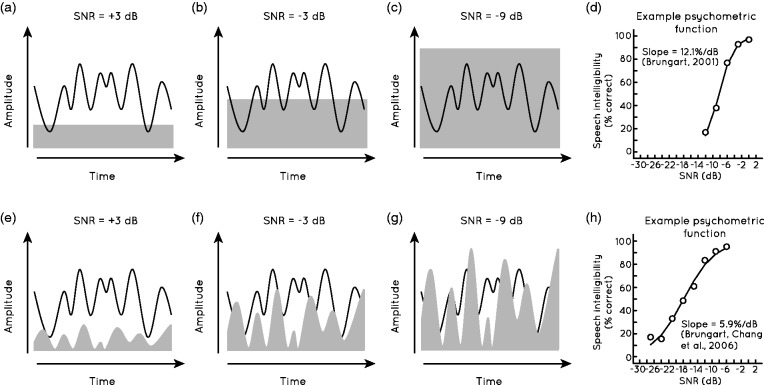

To measure how well the logistic equation fitted the data, a root mean square (RMS) error value of the curve from the data points was calculated. On the whole, the fits were regarded as good as the RMS was small (mean RMS = 3.2%). However, 29 psychometric functions had RMS values of 10% or greater and so were excluded from the survey at this stage (they are further discussed in the Nonmonotonic Psychometric Functions section). Figure 1 shows example data from the survey and illustrates some good, as well as some poor, fits of the logistic functions to the data.

Figure 1.

Example psychometric functions from the survey illustrating examples of good, average, below average, and poor fits of the standard logistic function (solid line) to the data (open circles). The RMS value gives an indication of the fit, with cases where the RMS value was above 10% being excluded from the survey. Cases that gave good fits include those for SSI sentences in a one-talker masker (Dirks & Wilson, 1969a), SPIN sentences in a six-talker babble (Elliott, 1979), and digits in a speech spectrum static noise (HearCom, 2009). Cases that had average fits (i.e., RMS values close to the mean for the survey) include those for SPIN sentences in a six-talker babble (Dirks, Bell, & Rossman, 1986), CRM sentences in an amplitude-modulated noise (Arbogast, Mason, & Kidd, 2002), and IEEE sentences in a Gaussian noise (Bernstein & Grant, 2009). Example cases that had below-average fits include those for CRM sentences in a two-talker masker (Wightman & Kistler, 2005), digits in a six-talker babble (Wilson et al., 2006), and invalid short tokens in a one-talker masker (Danhauer, Doyle, & Lucks, 1986). Examples of poor fits include valid sentences presented in a one-talker masker (Dirks & Bower, 1969) and CRM sentences in a one-talker masker (Brungart, 2001a).

After these removals, and those of cases whose slope values were based on extrapolation, 885 psychometric functions remained in the survey, taken from 139 different studies. Table 1 summarizes the stimuli and participant information for each study (all studies are listed in the references). Full details on all coded factors for each study (including those excluded) can be found in the supplementary material.

Table 1.

Key Details of All the Studies Included in the Systematic Survey.

| Study | N | Target corpus | Masker type | No. maskers | Masker corpus | Presentation | Age | Hearing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acton (1970) | 2 | PB word list | Static noise | – | – | Free field | Y | NH |

| Arbogast et al. (2002) | 24 | CRM | Speech and modulated noise | 1 | CRM | Free field | Y | NH |

| Barker and Cooke (2007) | 1 | Valid sentence | Modulated noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Beattie (1989) | 1 | W-22 | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | – | HI |

| Beattie, Barr, and Roup (1997) | 1 | W-22 | Speech | 20 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Beattie and Clark (1982) | 4 | SSI | Speech | 4 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Bernstein and Grant (2009) | 12 | IEEE | Speech, modulated, and static | 1 | HINT | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Best, Gallun, Mason, Kidd, and Shinn-Cunningham (2010) | 5 | CRM | Speech and static noise | 1 | CRM | Dichotic | Y | NH and HI |

| Bhattacharya and Zeng (2007) | 17 | Short tokens and HINT | Static noise | 1 | – | Diotic | Y | NH and CI |

| Blue-Terry and Letowski (2011) | 1 | Modified Rhyme Test | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Boothroyd (2008) | 4 | Short tokens | Static noise | – | – | – | Y | NH |

| Boothroyd and Nittrouer (1988) | 5 | Short tokens and invalid sentences | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Bosman and Smoorenburg (1995) | 17 | Short tokens, valid, and invalid sentences | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Bronkhorst, Bosman, and Smoorenburg (1993) | 4 | Short tokens | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Brungart (2001a) | 2 | CRM | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart (2001b) | 1 | CRM | Speech, modulated, and static | 1 | CRM | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart, Simpson, Ericson, and Scott (2001) | 16 | CRM | Speech and modulated noise | 1, 2, or 3 | CRM | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart, Darwin, Arbogast, and Kidd (2005) | 1 | CRM | Speech | 1 | CRM | Dichotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart, Chang, Simpson, and Wang (2006) | 6 | CRM | Modulated and static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart, Chang, Simpson, and Wang (2009) | 15 | CRM | Speech | 1, 2, or 3 | CRM | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart, Iyer, and Simpson (2006) | 8 | CRM | Speech | 1 | CRM | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart and Simpson (2002) | 5 | CRM | Speech, modulated, and static | 1 or 2 | CRM | Monaural/dichotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart and Simpson (2004) | 4 | CRM | Speech | 1 or 2 | CRM | Monaural/dichotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart and Simpson (2007) | 14 | CRM | Speech | 1, 2, or 3 | CRM | Monaural/dichotic | Y | NH |

| Brungart, Simpson, and Freyman (2005) | 3 | CRM | Speech and static noise | 1 | CRM | Free field | Y | NH |

| Cienkowski and Speaks (2000) | 1 | Short tokens | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Cooper and Cutts (1971) | 2 | NU-6 | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Craig (1988) | 9 | SPIN | Speech | 6 | SPIN | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Crandell (1993) | 1 | BKB | Speech | 6 | SPIN | Diotic | C | HI |

| Danhauer et al. (1986) | 3 | Invalid sentences | Speech, modulated, and static | 9 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Danhauer and Leppler (1979) | 3 | Short token | Speech and modulated noise | 4 or 9 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Darwin, Brungart, and Simpson (2003) | 9 | CRM | Speech | 1 | CRM | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Dirks, Bell, Rossman, and Kincaid (1986) | 3 | SPIN | Speech and static noise | 6 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Dirks and Bower (1969) | 37 | Valid sentences | Speech and modulated noise | 1 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Dirks, Morgan, and Dubno (1982) | 8 | NU-6 | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Dirks and Wilson (1969a) | 18 | Short token and SSI | Speech and static noise | 1 | Continuous | Diotic | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Study | N | Target corpus | Masker type | No. maskers | Masker corpus | Presentation | Age | Hearing |

| Dirks and Wilson (1969b) | 20 | PB word list | Static noise | 1 | Short tokens/PB | Free field and diotic | Y | NH |

| Dirks, Wilson and Bower (1969) | 42 | NU-6 | Modulated and static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Drullman (1995) | 2 | Valid sentences | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Drullman and Bronkhorst (2004) | 7 | Valid sentences | Speech | 1 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Dubno, Horwitz, and Ahlstrom (2005) | 2 | NU-6 | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Egan (1948) | 1 | Short tokens | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | – | – |

| Egan, Carterette, and Thwing (1954) | 1 | Valid sentences | Speech | 1 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Eisenberg, Dirks and Bell (1995) | 4 | SPIN | Modulated and static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Elliott (1979) | 6 | SPIN | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Diotic | C | NH |

| Erber (1971) | 3 | Short tokens | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Ezzatain, Li, Pichora-Fuller, and Schneider (2010) | 28 | Invalid sentences | Speech and static noise | 1 or 2 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Feeney and Franks (1982) | 4 | Short tokens, PB List, and Modified Rhyme | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Festen and Plomp (1990) | 6 | Valid sentences | Modulated noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Foster and Haggard (1987) | 1 | FAAF | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Freyman, Balakrishnan, and Helfer (2001) | 16 | Invalid sentences | Speech and modulated noise | 1 or 2 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Freyman, Balakrishnan, and Helfer (2004) | 16 | Invalid sentences | Speech and static noise | 1, 3, 5, or 9 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Freyman, Helfer, and Balakrishnan (2007) | 6 | Invalid sentences | Speech | 1 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Freyman, Helfer, McCall, and Clifton (1999) | 9 | Invalid sentences | Speech and static noise | 1 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Friesen, Shannon, Baskent, and Wang (2010) | 17 | Short tokens and HINT | Static noise | – | – | Free field | O | NH and CI |

| Fu, Shannon, and Wang (1998) | 9 | Short tokens | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Gelfand (1998) | 2 | Short tokens | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Grant and Braida (1991) | 7 | IEEE | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Griffiths (1967) | 4 | Modified Rhyme test | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Hagerman (1982) | 1 | Hagerman sentences | Modulated noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Hallgren, Larsby, and Arlinger (2006) | 1 | HINT | Static noise | – | – | Free field | Y | NH |

| HearCom (2009) | 13 | Digits and Matrix | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | – | – |

| Helfer and Freyman (2005) | 8 | Invalid sentences | Speech and static noise | 2 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Helfer and Freyman (2008) | 4 | Invalid sentences | Speech and modulated noise | 2 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Helfer and Freyman (2009) | 12 | TMV sentences | Speech | 1 or 2 | TMV sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Hirsh, Reynolds, and Joseph (1954) | 2 | Words and invalid sentences | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Horii, House, and Hughes (1971) | 2 | Vowels and consonants | Modulated and static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| House, Williams, Hecker, and Kryter (1965) | 1 | Words | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Howard-Jones and Rosen (1993) | 5 | Words | Modulated and static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Ihlefeld and Shinn-Cunningham (2008) | 3 | CRM | Speech | 1 | CRM | Dichotic | Y | NH |

| Jerger and Jordan (1992) | 2 | Continuous speech | Speech | 1 | Continuous | Free field | Y | NH |

| Jerger, Jerger, and Lewis (1981) | 2 | PSI Test | Speech | 1 | PSI Test | Free field | Y | NH |

| Johnstone and Litovsky (2006) | 12 | Spondees | Speech and modulated noise | 1 | IEEE | Free field | C and Y | NH |

| Kalikow et al. (1977) | 4 | SPIN | Speech | 12 | Valid Sentences | Diotic | Y and O | NH |

| Kates and Arehart (2005) | 1 | HINT | Modulated noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Study | N | Target corpus | Masker type | No. maskers | Masker corpus | Presentation | Age | Hearing |

| Keith and Talis (1970) | 3 | W-22 | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Kidd, Mason, and Gallun (2005) | 3 | CRM | Speech and static noise | 1 or 2 | CRM | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Krull, Choi, Kirk, Prusick, and French (2010) | 3 | Words | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | C | NH |

| Kryter (1962) | 7 | Syllables, PB, MRT and valid sentence | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Kryter and Whitman (1965) | 1 | PB words and MRT | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Lewis, Benignus, Muller, Malott, and Barton (1988) | 3 | SPIN | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Li, Daneman, Qi, and Schneider (2004) | 18 | Invalid sentences | Speech and static noise | 2 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y and O | NH |

| Li and Loizou (2009) | 7 | IEEE | Speech and static noise | 2 | IEEE | Diotic | Y | NH |

| MacLeod and Summerfield (1990) | 1 | ASL | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Martin and Mussell (1979) | 2 | Words and SSI | Speech and static noise | 2 | Valid sentences | Dichotic | Y | ? |

| McArdle, Wilson, and Burks (2005) | 5 | NU-6, digits, and IEEE | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Miller, Heise, and Litcten (1951) | 13 | Syllables, words, digits, and valid sentences | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | ? | ? |

| Ng, Meston, Scollie, and Seewald (2011) | 6 | BKB | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Free field | C | NH and HI |

| Neiderjohn and Grotelueschen (1976) | 4 | PB Lists | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Nielsen and Dau (2009) | 2 | HINT | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Oxenham and Simonson (2009) | 12 | HINT | Speech and modulated noise | 1 | IEEE | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Ozimek, Kutzner, Sek, and Wicher (2009) | 1 | Valid sentences | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Ozimek, Warzybok, and Kutzner (2010) | 1 | Matrix | Speech | 6 | Matrix | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Pederson and Studebaker (1972) | 2 | Words | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Pichora-Fuller et al. (1995) | 6 | SPIN | Speech | 8 | SPIN | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Pichora-Fuller, Schneider, MacDonald, Pass, and Brown (2007) | 4 | SPIN | Speech | 8 | SPIN | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Plomp and Mimpen (1979) | 1 | Valid sentences | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Rakerd, Aaronson, and Hartmann (2006) | 3 | CRM | Speech | 2 or 3 | CRM | Free field | Y | NH |

| Rao and Letowski (2006) | 5 | CAT test | Speech and static noise | 6 | CAT test | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Rogers, Lister, Febo, Besing, and Abrams (2006) | 3 | W-22 | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Schultz and Schubert (1969) | 2 | W-22 and MCDT | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | ? | ? |

| Scott, Rosen, Wickham, and Wise(2004) | 1 | BKB | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Sergeant, Atkinson, and Lacroix (1979) | 3 | TTI, MRT, and CID | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Sherbecoe and Studebaker (2002) | 2 | CST | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Speaks and Karmen (1967) | 1 | Valid sentences | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Speaks, Karmen, and Benitez (1967) | 4 | SSI | Speech | 1 | SSI | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Speaks, Parker, Kuhl, and Harris (1972) | 3 | Continuous speech | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Stickney, Zeng, Litovsky, and Assmann (2004) | 10 | IEEE | Speech and static noise | 1 | IEEE | Monaural | Y | NH and CI |

| Studebaker, Taylor, and Sherbecoe (1994) | 4 | Words | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Surprenant (2007) | 1 | Syllables | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y and O | NH |

| Surr and Schwartz (1980) | 1 | CCT | Speech | 12 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y | HI |

| Suter (1985) | 4 | MRT and CID | Speech | 12 | Valid sentences | Monaural | ? | HI |

| Tabri, Smith Abou Chacra, and Pring (2011) | 8 | SPIN | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Study | N | Target corpus | Masker type | No. maskers | Masker corpus | Presentation | Age | Hearing |

| Takahashi and Bacon (1992) | 8 | SPIN | Modulated and static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Theodoridis and Schoeny (1988) | 3 | W-22 | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Theodoridis, Schoeny, and Anné (1985) | 2 | W-22 | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Thomas and Ravindran (1974) | 3 | PB words | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | ? | ? |

| Trammell and Speaks (1970) | 2 | Valid sentences | Speech | 1 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Tun (1998) | 6 | Valid sentences | Speech | 20 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y and O | NH |

| Van Wieringen and Wouters (2008) | 4 | Digits and LIST | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Vestergaard, Fyson, and Patterson (2009) | 3 | Syllables | Speech and static noise | 1 | Syllables | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Wagener, Josvassen and Ardenkjoer (2003) | 1 | Dantale 2 | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Whitmal, Poissant, Freyman, and Helfer (2007) | 6 | Syllables and valid sentences | Speech and static noise | 1 or 2 | Invalid sentences | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Wightman and Kistler (2005) | 28 | CRM | Speech and static noise | 1 or 2 | Invalid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Williams and Hecker (1968) | 1 | HINT | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Wilson and Antablin (1980) | 2 | PIT and NU-6 | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Wilson and Burks (2005) | 3 | Words | Speech | 6 | Words | Monaural | O | HI |

| Wilson, Burks, and Weakley (2006) | 12 | NU-6 and digits | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Diotic | O | HI |

| Wilson, Carnell, and Cleghorn (2007) | 4 | Words | Speech and static noise | 6 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Wilson and Cates (2008) | 2 | Words | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Wilson, Farmer, Gandhi, Shelburne, and Weaver (2010) | 8 | Words | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | C and Y | NH |

| Wilson and McArdle (2007) | 4 | Words | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Diotic | O | HI |

| Wilson et al. (2010) | 13 | Words | Speech, modulated, and static | 6 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Wilson, McArdle, and Roberts (2008) | 14 | PB, W-22, NU-6, and digits | Static noise | – | – | Monaural | Y | NH |

| Wilson, McArdle, and Smith (2007) | 6 | Words, IEEE, and BKB | Speech | 6 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Wilson and Oyler (1997) | 2 | W-22 and NU-6 | Static noise | – | – | Diotic | Y | NH |

| Wilson and Strouse (2002) | 8 | NU-6 | Speech | 1 | Valid sentences | Diotic | Y and O | NH and HI |

| Wu et al. (2005) | 6 | Invalid sentences | Speech and static noise | 1 or 2 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Yang et al. (2007) | 18 | Syllables and words | Speech and static noise | 1 or 2 | Invalid sentences | Free field | Y | NH |

| Young, Goodman, and Carhart (1979) | 3 | Words | Speech | 5 | Valid sentences | Monaural | Y | NH |

Note. C = children; Y = young adults; O = older adults; NH = normal hearing; HI = hearing impaired; CI = cochlear implant user. For speech corpus codes, see note 3.

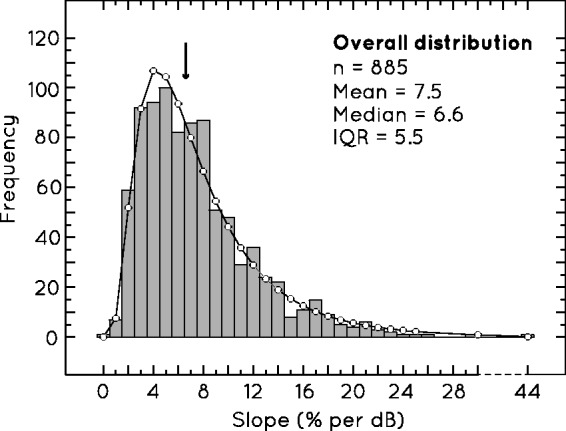

It was found that a log-normal distribution (Buzsáki & Mizuseki, 2014; Johnson & Kotz, 1970) gave an excellent fit to the overall frequency distribution of slope values:

| (2) |

where f is frequency and s is slope. The best fitting values of θ and σ were found using Excel's Solver, which gave values of 1.46 and 0.63, respectively. Figure 2 shows the overall distribution of slope values and this best-fitting log-normal curve. It can be seen that there is a very wide variation in the slope. The minimum and maximum values of slope were 0.4% per dB and 43.8% per dB, the mean was 7.5% per dB, and the median was 6.6% per dB. There was a clear positive skew, with the bulk of values, including the median, lying to the left side of the mean.

Figure 2.

The overall distribution of slope values measured in the systematic slope survey, across all 885 cases (see Equation 2). The solid line is a log-normal distribution fitted to the data. The median for the distribution is indicated by an arrow.

Major Trends

With 885 cases, it is not too surprising to find substantial variations across details of stimuli, maskers, and other aspects of experimental design. The analysis here therefore concentrates on broad categories rather than on specific individual combinations. The full data set is available in the supplementary material.

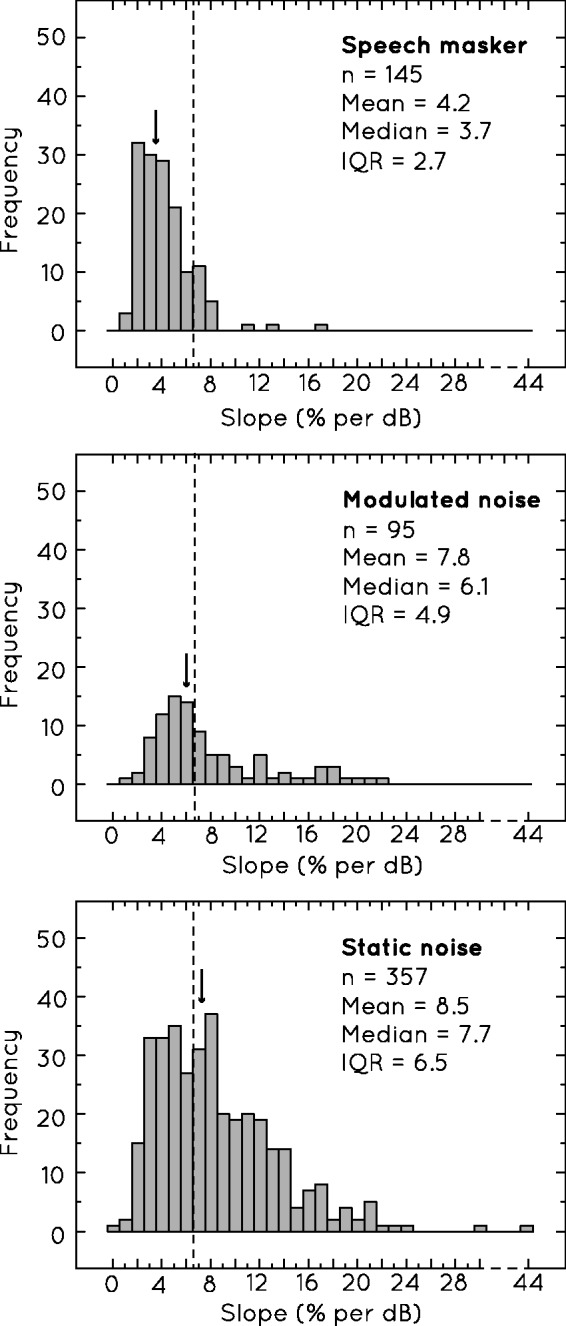

Type of masking noise

The first major trend in the slope survey data is that speech maskers give shallower psychometric functions than either amplitude-modulated noise maskers or static noise maskers. Table 2 shows the median slopes and interquartile ranges of psychometric functions measured for the six general classes of speech stimuli and the seven most commonly reported speech corpora when different types and numbers of maskers were used. Table 3 shows the number of studies and the number of individual psychometric functions that these values are based on.4 It can be noted from Table 2 that of the 11 different target speech types for which slopes have been measured in both a speech masker and a noise masker (be it either modulated noise or static noise), eight of them gave smaller median slope values for psychometric functions measured in a speech masker than they did in a noise masker (namely, Words, Valid sentences, Invalid sentences, Continuous speech, CRM, HINT, SSI, and Other).

Table 2.

Median Slope Values for Each of the Primary Target/Masker Combinations Identified in the Survey.

| Masker | Short tokens | Words | Digits | Valid sentences | Invalid sentences | Continuous speech | CRM | HINT | IEEE | NU-6 | PB lists | SPIN | SSI | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Speech masker | 5.1 (3.3) | 6.7 (2.2) | – | 2.5 (1.2) | 6.5 (4.2) | 5.7 (–) | 3.7 (1.5) | 3.4 (2.0) | 4.5 (1.3) | – | – | 8.7 (–) | 4.6 (3.2) | 4.2 (1.6) |

| 2 Speech maskers | 7.9 (2.2) | 7.7 (–) | – | 7.7 (5.5) | 6.3 (1.4) | – | 4.2 (3.5) | – | 4.3 (–) | – | – | – | – | 9.8 (3.4) |

| 3 Speech maskers | – | – | – | – | 15.1 (–) | – | 9.2 (2.4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 + Speech maskers | 2.3 (–) | 7.5 (2.1) | 9.9 (3.6) | 9.5 (0.8) | 9.1 (2.5) | – | – | – | 15.9 (–) | 6.2 (3.3) | – | 8.2 (7.2) | 13.2 (4.5) | 8.4 (3.5) |

| 1 Modulated noise masker | 3.4 (2.3) | 8.3 (5.8) | – | 13.5 (–) | 7.3 (0.9) | – | 5.8 (2.2) | 4.6 (–) | 4.3 (1.1) | 5.8 (2.7) | – | 3.1 (5.5) | 14.7 (7.4) | 5.2 (–) |

| 2 Modulated maskers | – | – | – | 5. 0 (–) | – | – | 8.1 (–) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 Modulated maskers | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10.2 (–) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 Static noise masker | 4.0 (4.4) | 8 2 (6.0) | 13.4 (6.1) | 12.3 (6.5) | 8.1 (2.1) | 7.2 (–) | 10.1 (3.5) | 9.1 (5.5) | 4.8 (3.8) | 5.2 (2.6) | 6.1 (3.4) | 4.7 (7.1) | 17.1 (4.2) | 5.9 (7.6) |

| 2 Static noise maskers | – | – | – | – | 8.8 (1.0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mixed | – | 15.2 (–) | – | 2.7 (–) | 1.9 (–) | – | 4.5 (1.8) | – | – | – | – | – | 13.6 (–) | 6.0 (–) |

Note. Interquartile ranges for each condition are given in parentheses.

Table 3.

Number of Studies Reporting Data for Each of the Target/Masker Combinations in Table 2.

| Masker | Short tokens | Words | Digits | Valid sentences | Invalid sentences | Continuous speech | CRM | HINT | IEEE | NU-6 | PB lists | SPIN | SSI | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Speech masker | 2/10 | 1/4 | – | 5/46 | 3/13 | 1/2 | 8/41 | 1/6 | 2/10 | – | – | 1/1 | 2/10 | 1/2 |

| 2 Speech maskers | 1/6 | 1/3 | – | 2/9 | 5/38 | – | 7/42 | – | 1/3 | – | – | – | – | 1/10 |

| 3 Speech maskers | – | – | – | – | 1/2 | – | 4/20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 + Speech maskers | 2/3 | 6/13 | 2/13 | 2/7 | 1/4 | – | – | – | 2/3 | 4/19 | – | 7/31 | 1/4 | 9/26 |

| 1 Modulated noise masker | 2/5 | 3/23 | 2/3 | 1/4 | 4/21 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 1/11 | 2/6 | 1/12 | 3/3 | |||

| 2 Modulated maskers | – | – | – | 1/1 | – | – | 1/1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 3 Modulated maskers | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 1 Static noise masker | 13/55 | 13/63 | 4/19 | 14/32 | 6/34 | 1/3 | 5/9 | 6/19 | 4/19 | 6/9 | 8/27 | 4/9 | 2/8 | 27/51 |

| 2 Static noise maskers | – | – | – | – | 1/4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Mixed | – | 1/1 | – | 1/3 | 1/2 | – | 3/15 | – | – | – | – | – | 1/1 | 1/3 |

Note. Number of individual cases is given in bold.

Figure 3 shows the overall distributions of slope values found for three different masker types: speech, modulated noise, and static noise.5 In an attempt to disentangle the effect of the type of masker used from the slope effect seen when the number of maskers was increased (see Number of Masking Noises section), only cases where a single masker was used were included in this figure. There is a substantial difference between the three distributions: the measures of central tendency (i.e., median and mean slope values) decreased in value from static noise maskers (median = 7.7% per dB) through modulated noise (median = 6.1% per dB) to speech maskers (median = 3.7% per dB). This last median was considerably shallower than that of the overall median slope reported earlier (median = 6.6% per dB), suggesting that the shallowest end of the distribution was more densely populated by cases that used speech maskers.

Figure 3.

The distributions of slope values for three different categories of masker: speech, amplitude-modulated noise, and static noise. The dotted lines indicate the overall median slope value for the survey, while the arrows indicate the median slope value for each specific distribution. Only cases where one masker was used are included.

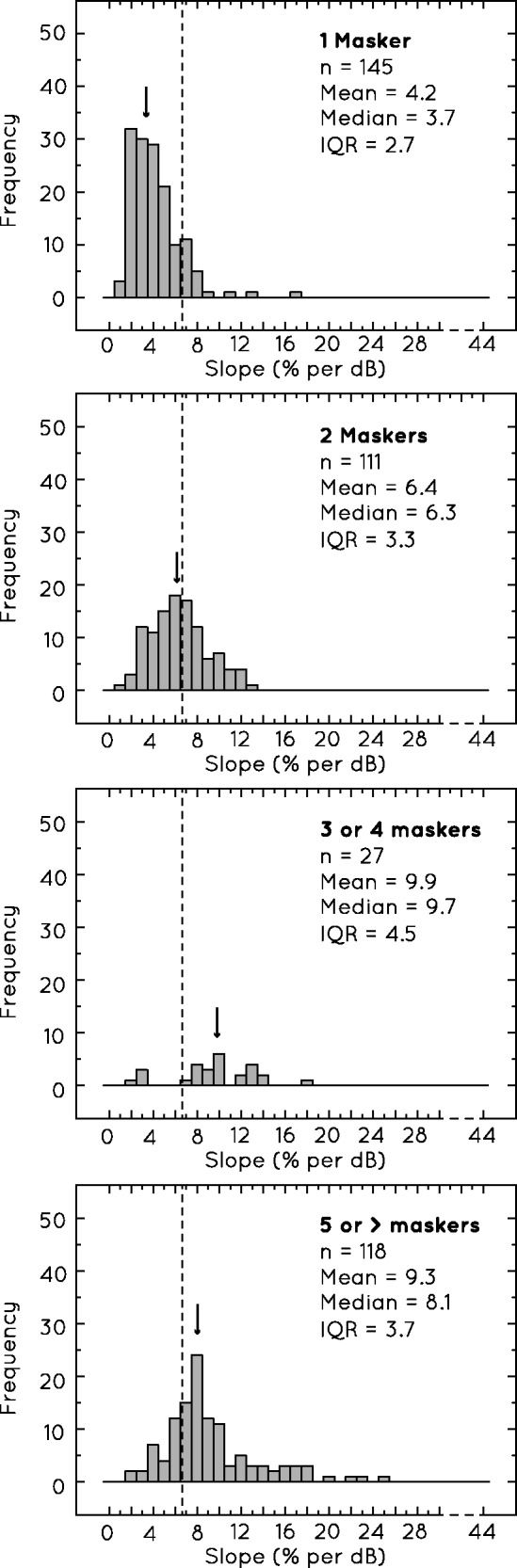

Number of masking noises

The second major trend is that the slope of the psychometric function tends to increase as the number of maskers increases, at least up to approximately three or four maskers. Table 2 shows that increasing the number of speech maskers from one to two increases the slope by, on average, 4% per dB, which begins to approach the values produced by either a modulated noise or static noise masker.

Figure 4 shows the distribution of slope values as a function of the number of maskers used. To avoid a confound of the effect of masker type on slope, only psychometric functions measured using speech maskers were included.6 It can be seen that the distributions were shifted to the right and to larger values as the number of maskers was increased from one to two, to three or more. Only in the one-masker condition was the median slope value (median = 3.7% per dB) below that of the overall median slope value shown in Figure 2. The distribution in the bottom panel is for cases with 5–20 speech maskers. The distribution, mean, and median slope values for this condition were very similar to those found when three or four maskers were used. This would suggest that once the number of maskers reached three or four, any additional maskers had a negligible effect on the slope.

Figure 4.

The distributions of slopes found when one, two, three or four, or greater than five maskers were used. The dotted line indicates the overall median slope value for the survey, while the arrow indicates the median slope value for each specific distribution. Only cases where speech maskers were used are included.

Minor Trends

Although the type and number of maskers used had a large effect on slope, these factors cannot solely account for all the slope variation seen in the survey. For example, there was a range of 16% per dB between the lowest and highest slope values for cases with one speech masker (see Figure 4, top panel). Several more minor trends in slope will now be briefly described.

Predictability of target speech

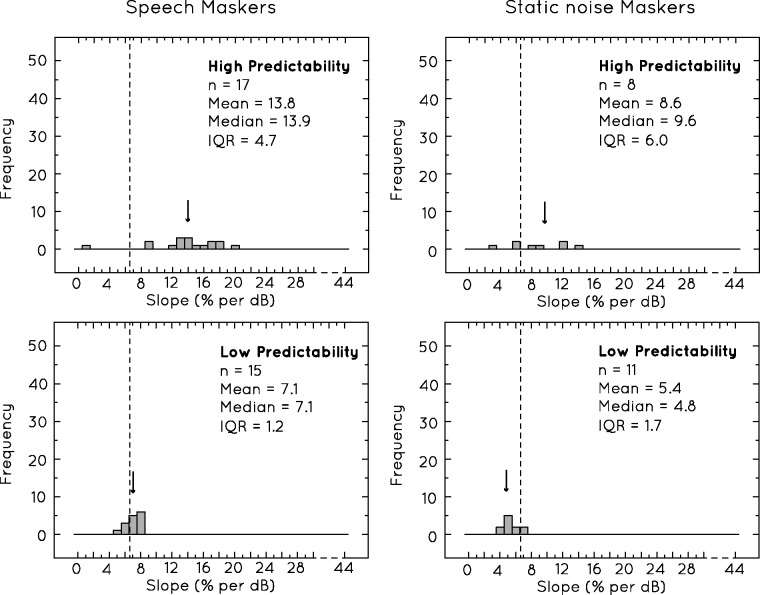

Figure 5 compares the slopes of psychometric functions for highly predictable speech targets with those for less predictable speech targets. The data came principally from experiments where the SPIN sentences (Kalikow, Stevens, & Elliot, 1977) were used as targets, as this is the main corpus in which the degree of target predictability is manipulated. The left column includes slope values for speech maskers, whereas the right column includes slope values for noise maskers.7 For the speech maskers, a clear effect was found, with less predictable targets producing markedly shallower slopes (median = 7.1% per dB) than highly predictable targets (median = 13.8% per dB). This slope difference was reduced if the masker was noise; however, here, the low-predictability median slope was 5.4% per dB and the high-predictability median slope was 8.6% per dB. In addition to a difference in median slope values, there was also a difference in the width of the distributions of the slope values between the high and the low predictable targets: When either speech or static noise maskers were used, broader slope distributions were seen for the highly predicable targets than for the less predictable targets.

Figure 5.

The different distributions of slope values found when there was either a high or low probability of target speech being predicted from previous context. The left panels plot these distributions for speech maskers, while the right panels plot these distributions for static noise maskers. The dotted lines indicate the overall median slope value for the survey, while the arrows indicate the median slope value for each specific distribution. Only cases where one masker was used are included.

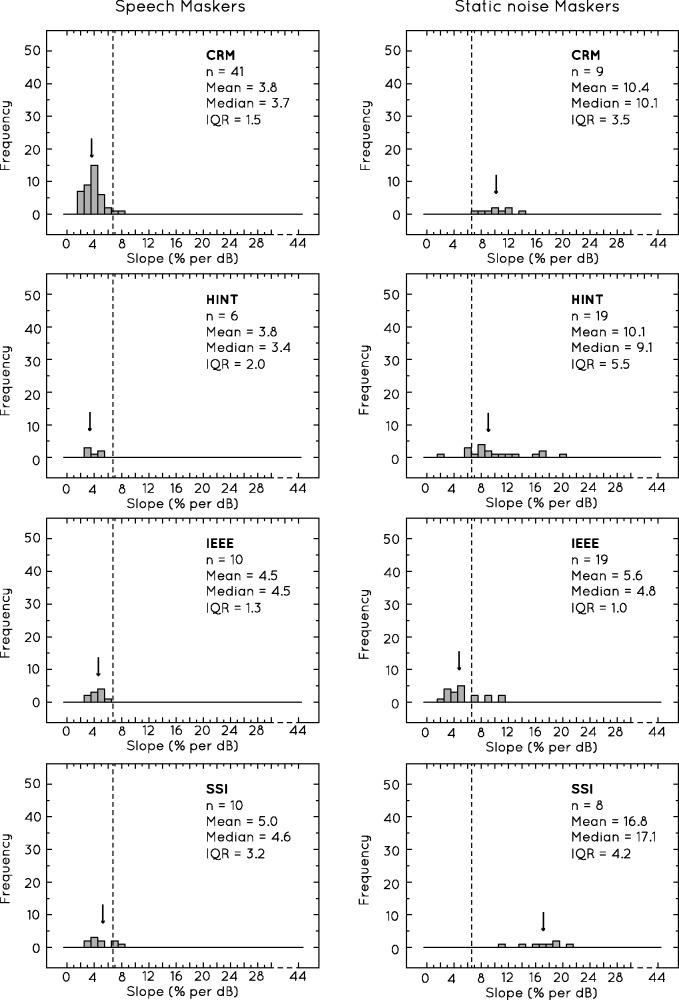

Target corpus

Figure 6 shows the distributions of slope values for targets taken from various corpora. The slopes measured using four standard speech tests (CRM, HINT, IEEE, and SSI) are displayed separately for speech maskers (left column) and static noise maskers (right column).8 The data show that when a speech masker is used, the choice of target corpus has little effect on slope (median slopes = 3.7%, 3.4%, 4.5%, and 4.6% per dB for CRM, HINT, IEEE, and SSI, respectively), but a large variation in slope is seen when the masker was a static noise (median slopes = 10.1%, 9.1%, 4.8%, and 17.1% per dB; IEEE gave the lowest while SSI gave the highest).

Figure 6.

The distribution of slope values found for four different speech corpora (CRM, HINT, IEEE, and SSI), when they were presented in speech maskers (left panels) and when they were presented in static noise maskers (right panels). Again the dotted lines in each panel indicate the overall median, while the arrows indicate the median for each category of target, and only cases where one masker was used are included.

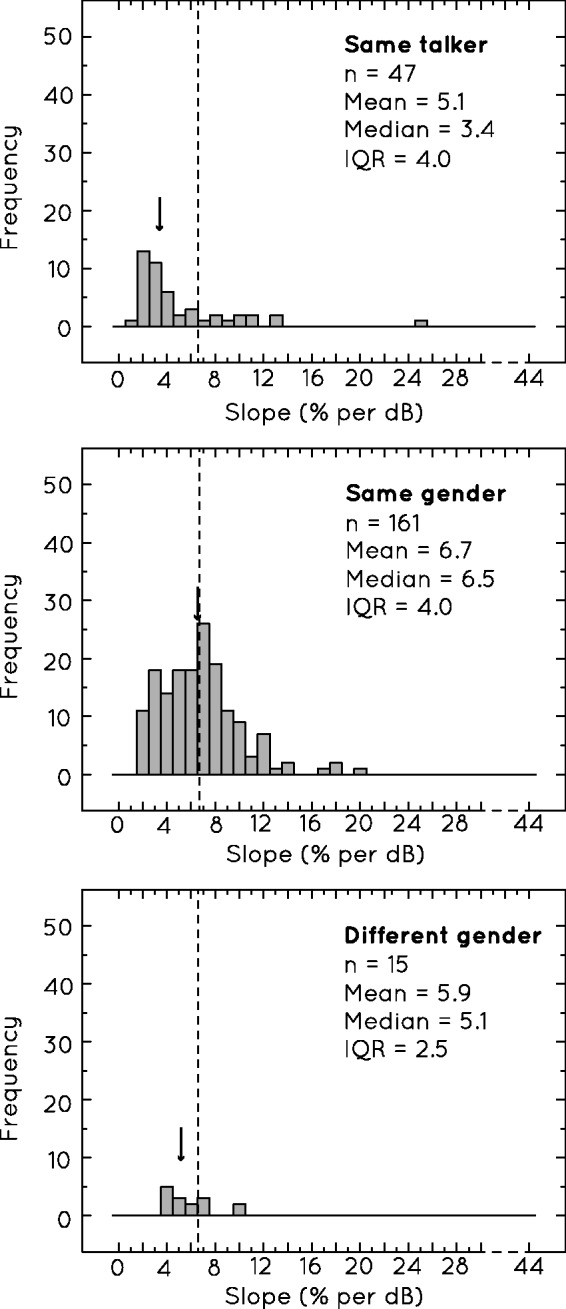

Similarity of target and masker voices

Figure 7 shows the distributions of slope values for varying degrees of target/masker voice similarity. The subcategories of similarity include (unprocessed)9 target and maskers spoken by the same talker, by a different person of the same gender, or by a person of a different gender. These subcategories include cases where only one speech masker was used. The slopes for the same talker category were shallower than those for talkers of different genders (medians of 3.4% compared with 5.0% per dB). The distribution of slopes given when the target and masker were of the same gender but spoken by different people, however, overlaps with each of the other distributions. This wider distribution may reflect the greater variation in similarity for this subcategory, that is, some same-gender voices were likely to be more similar than others.

Figure 7.

The distributions of slope values found for speech maskers with three different levels of talker similarity to the target speech: same talker, same gender talker, and different gender talker. The dotted lines indicate overall median slope, while the arrows indicate individual medians for each distribution. Only cases where one masker was used are included.

Other minor effects

Prior exposure to, or priming, some aspects of either the target or masker before a trial also affects the slope of the psychometric function. Slope values tended to be slightly steeper when either the target or masker sentence was primed compared with when no prime was presented (medians of 7.8% per dB, n = 27 compared with 5.9% per dB, n = 374 for speech maskers, and 8.9% per dB, n = 19 compared with 7.4% per dB, n = 342 for the static noise maskers). Primed cases included (a) acoustic primes, where target or masker voices were primed, (b) linguistic primes, where the content of the target or masker was primed, and (c) dual primes, where both the acoustic and content of the target or masker were primed (e.g., the prime was the start of the test sentence).

The content of the masking speech also has a small effect on slope. When the content of the masker was very similar to that of the target, for example, when they were taken from the same speech corpus, slopes tended to be shallower (median = 4.6% per dB, n = 117) than when the masker content was more linguistically distinct from the target, that is, when they were taken from different speech corpora (median = 6.5% per dB, n = 281). More generally, masking speech whose content was meaningful gave shallower psychometric functions (median = 4.0% per dB, n = 203) than those with non-meaningful content (e.g., time-reversed speech, foreign language speech, invalid sentences, or babble; median = 7.3% per dB, n = 215).

There was also an indication that listener age had an effect on the slope of the psychometric function. There was a trend of increasing slope with age when a speech masker was used (n = 34, 299, and 63, medians = 4.6% per dB, 5.8% per dB, and 7.1% per dB for children, young adults, and older adults, respectively). No effect of age on slope was evident, however, when a static noise masker was used (n = 10, 248, and 44, medians = 8.3% per dB, 7.4% per dB, and 7.8% per dB, for children, young adults, and older adults, respectively).

The hearing ability of the listeners (normal hearing, hearing impaired, or cochlear implant user) was coded for in the survey. In cases using a speech masker, there was a trend of increasing slope with hearing impairment (medians = 6% per dB and 7.5% per dB, n = 345 and 55 for normal hearing and hearing-impaired listeners, respectively); however, a reverse trend was observed in cases using a static noise masker, with slope decreasing with increased impairment (medians = 7.8% per dB, 5.9% per dB, and 2.7% per dB, n = 312, 34, and 15 for normal hearing, hearing-impaired listeners, and cochlear implant users, respectively).

The results for the effect of age and hearing impairment on slope are somewhat tentative, however, as the sample sizes of the groups were particularly unequal in both types of comparison. Further, the two effects are difficult to disentangle as in 98% of cases including young listeners, the listeners were also normal hearing, and in 70% of cases including older listeners, the listeners were also hearing impaired, thus partially confounding the effects of age and hearing impairment.

Nonmonotonic Psychometric Functions

As previously noted, any cases where the data had to be extrapolated to fit a logistic function, or cases where the logistic functions were a poor fit to the data, were excluded from the slope survey. The latter was mostly due to extremely shallow or unusual psychometric functions. These generally took two forms: functions where performance plateaued over a specific SNR range (usually −12 to 0 dB) before increasing at higher SNRs, and functions with dips where performance instead decreased over this SNR before increasing (see Figure 1, bottom panels). Twenty-three of the cases that were excluded from the survey due to high RMS values were nonmonotonic in shape (e.g., plateaus or dips).

The majority of functions in this subset were from speech maskers where only one masker was used (19 of 23). While these nonmonotonic psychometric functions were measured using several different speech stimuli, the two largest contributors were from using CRM stimuli (10/23) and valid sentences (5/23). Most occurred when the same talker was used in the target and the masker (18/23), whether the target was unprocessed (9/23), processed (e.g., vocoded, 7/23), or mixed with other maskers (2/23). The listening conditions giving the shallowest slopes fit with the trends reported earlier for shallow slopes identified in the main slope survey.

Discussion

We systematically surveyed the published data on the psychometric functions for speech intelligibility to identify the main factors that affect its slope. Large variations in slope were found, with slopes ranging from as shallow as 1% per dB to as steep as 44% per dB. The median value across 139 studies (885 cases) was 6.6% per dB. The type and number of maskers used were major factors on the value of the slope of the psychometric function. Other minor effects of target predictability, target corpus, and target/masker similarity were also found. There was also an indication that age and hearing impairment might also affect slope, although it was not possible for the current survey to completely disentangle these two effects.

Slope Changes as a Consequence of Fluctuating Maskers

Our analyses have clearly demonstrated that masker type affects the slope of the psychometric function, with speech maskers found to give shallower slopes than noise maskers, be they amplitude modulated or static noise. The number of speech maskers used also affected the slope of the psychometric function, with the slope of the function increasing as the number of maskers was increased from one to about three or four. Given that speech can be thought of as the sum of multiple amplitude-modulated frequency bands (Drullman, Festen, & Plomp, 1994) and that increasing the number of maskers will alter the quality of the amplitude variations (Cooke, 2006; Miller, 1947), both of these effects indicate the importance of masker amplitude modulations on slope.

The effects of amplitude modulation on slope can be understood by considering glimpsing (Figure 8). When target speech is presented in a fluctuating masker, there will be instances in which the speech sounds coincide with amplitude minima (or dips) in the masking waveform. In these dips local SNR is increased, allowing the listener to glimpse the target speech signal (Cooke, 2006; Miller & Licklider, 1950). These glimpses can greatly improve speech intelligibility and so lower speech reception thresholds, as the information they provide can help to identify even the parts of the speech that are still masked (Miller, 1947; Takahashi & Bacon, 1992; Wilson & Carhart, 1969). Thus, amplitude modulations increase the SNR range over which target speech will remain audible (Rhebergen & Versfeld, 2005), as glimpses of target speech may remain even as SNR is decreased. The result is a shallower psychometric function for modulated maskers than for static maskers (Speaks et al., 1967).

Figure 8.

A schematic illustration of the nonlinear increase in speech intelligibility that arises with amplitude-modulated maskers. Panels (a) to (c) represent a speech signal presented in a static noise. As SNR is decreased (i.e., the masker is increased), the proportion of the signal that is audible decreases, as does speech identification. Panels (e) to (g) illustrate the same speech signal presented in an amplitude-modulated noise. This time, as SNR decreases, glimpses of the target are still available, which can be used to aid in speech identification. Even at the lowest SNR in Panel (g), a large proportion of these glimpses still remain. Panel (d) shows an example psychometric function for speech (CRM sentences) in a static noise, and Panel (h) shows an example psychometric function for the same speech stimuli in an amplitude-modulated masker.

When a single competing talker is used as the masker, the temporal fluctuations are relatively slow, and there are likely to be many opportunities where the target speech will coincide with a dip in the amplitude of the masker, that is, there will be many opportunities for glimpsing the target speech (Miller & Licklider, 1950). As more maskers are added, the spectral and temporal dips begin to fill (Cooke, 2006; Miller, 1947). The chance that the target will temporally overlap with at least one of the maskers becomes greater, and overall amplitude modulations in the masking mixture effectively become shallower and briefer. The opportunities for glimpsing the target, therefore, become fewer. The reduced opportunity for glimpsing leads to an increase in slope. In the extreme case, if enough voices are added to the masking signal, then it would approach that of a speech-shaped static noise (e.g., Cooke noted that when six or more masking voices were present, intelligibility was not significantly different from that of a speech-shaped static noise masker). Our analyses demonstrate that only three or four masking voices are needed before the slopes of psychometric functions became equivalent to those given by a static noise.

Curiously, we found that amplitude-modulated noises did not give substantially shallower slopes than the static noise maskers, as might be expected by this glimpsing argument (see Figure 3). This could possibly be explained by the wide range of maskers that fell into the category of modulated noise, that is, any noise masker whose amplitude was temporally varied regardless of modulation depth, frequency, or duration. Modulation depths ranged from 1 to 48 dB, and modulation rates varied from 1 to 100 interruptions per second. Not all modulated maskers will result in a flattening of the psychometric function; for instance, only fluctuations with relatively long durations (greater than 200 ms) have been found to give shallower psychometric functions than nonmodulated maskers (Howard-Jones & Rosen, 1993). It is likely that the survey did not capture the subtle effects that experimental manipulation of amplitude modulations has on slope over and above the consistent modulations exhibited by speech maskers.

There was an indication from the survey that older, hearing-impaired listeners tended to give steeper psychometric functions than young normal hearing listeners when speech was presented in a competing speech masker. This finding accords with the slope pattern that would be expected if this listener group were less able to make use of brief dips in the power of background noise to help identify target speech, as has previously been suggested (e.g., Festen & Plomp, 1990). This reduced glimpsing ability for older, hearing-impaired listeners has been attributed to a reduced temporal resolution (Lutman,1991; Schneider, 1997) and, in the case of listeners with normal hearing thresholds but with deficits listening in noisy environments, to reduced fidelity when encoding suprathreshold sounds (Bharadwaj, Verhulst, Shaheen, Liberman, & Shinn-Cunningham, 2014). Reduced glimpsing would, in general terms, result in an amplitude-modulated masker acting more like a static noise masker, which would lead to a steeper psychometric function.

Slope Changes as a Consequence of Target/Masker Confusion

The slope survey identified 23 cases where the psychometric function was nonmonotonic. Most of these functions were produced when a speech masker was used, and nearly all of those functions were given when at least one of the speech maskers was spoken by the same voice as the target. These results suggest that a high degree of similarity between the target and the masker is required to give nonmonotonic psychometric functions. The survey also demonstrated that even when psychometric functions were monotonic, manipulating the acoustic similarity of the target to the speech masker affected the slope, as shallower slopes were found when the target and masker voices were spoken by the same person than when they were spoken by people of different genders. Linguistic similarity between the target and masker, that is, if they were both taken from the same speech corpus, also tended to result in shallower psychometric functions. Conversely, there was the suggestion that providing a cue that could aid in the differentiation of a target from a masker when both were speech, such as providing a prime of the target voice or content, could steepen the slope of the psychometric function. These effects combined indicate that the degree of confusion that exists between a target and a masker can be a factor in the resultant slope of the psychometric function.

The role of confusion on slope can be explained by increased reliance on a level difference between target and masker signals (Brungart, 2001a; Dirks & Bower, 1969; Egan et al., 1954). Such reliance is thought to occur when difficulties arise disentangling elements of a target signal from a similar sounding masker signal. In such cases, if the target is either less intense or more intense than a masker, then the level difference can be used as a cue to distinguish which sound is which. The greater the reliance that is placed on this cue, the more dissociated intelligibility is likely to become from overall SNR. Intelligibility can in principle be better at negative SNRs, where a clear level difference exists between the two signals, than at SNRs near zero, where the level difference is smaller. Extreme confusion between a target and a masker (i.e., where both signals are spoken by the same person) can, therefore, have the effect of flattening the slope of the psychometric function or even giving a dip in the function near 0 dB (i.e., where there is no level difference cue available).

Slope Changes as Consequence of the Availability of Top-Down Information

The survey demonstrated that target stimuli that contained keywords that were predictable from their content gave steeper slopes than those whose keywords were unpredictable. It was also demonstrated that targets taken from some speech corpora gave shallower slopes than others. The speech corpora whose targets tended to give shallow slopes were commonly open-set such as the IEEE corpus (Rothauser et al., 1969). Conversely, targets taken from closed-set corpora, such as the SSI (Speaks & Jerger, 1965), gave the steepest slopes. These effects indicate that the relative contributions of perceptual and cognitive factors may influence slope.

Pichora-Fuller et al. (1995) suggested that congruent previous context constrains possible word options, shifting the influence of word identification from perceptual (bottom-up) to cognitive (top-down) information. The mechanism is essentially positive feedback; with a greater dependence on top-down information, word identification can increase more rapidly with changes in level as small increases in acoustic information may be sufficient to further constrain possible speech elements. The probability of other speech elements then being guessed correctly increases, resulting in a steepening of the psychometric function (Bronkhorst et al., 1993). If, however, there is little top-down information available to constrain word options or if this information is incongruent with the rest of the utterance (as is the case when keywords are unpredictable), intelligibility will be based on bottom-up information alone and will thus increase more slowly as level is increased, giving a relatively shallow psychometric function. Several individual studies have clearly demonstrated this effect (Dirks et al., 1986; Dubno, Ahlstrom, & Horwitz, 2000; Elliott, 1979; Kalikow et al., 1977; Lewis et al., 1988; Pichora-Fuller et al., 1995).

Aside from slopes being generally steeper when target speech could be predicted from its context, it was also noted in the current survey that distributions of slope values tended to be broader for such targets than for those whose content was unpredictable. It is possible that this difference in slope distributions reflects a variation in the reliance on context and top-down information by different listeners across studies. It has been suggested, for example, that older listeners can benefit more from supportive context than younger listeners can (Pichora-Fuller et al., 1995). A greater reliance on context would, as mentioned earlier, have a tendency to steepen the slope of the psychometric function while a greater reliance on perceptual information would have a tendency to flatten the slope of the psychometric function. A shift in the balance of these two strategies may, in part, be the reason that steeper slopes were seen in the current survey for older, hearing-impaired listeners than for younger, normal hearing listeners, and the greater variation in the use of context by listeners across studies may explain the broader slope distribution for predictable, compared with unpredictable, target utterances.

The number of possible responses available in a speech test can also alter the relative contributions of perceptual and cognitive factors in speech identification. The SSI, for example, is usually presented as a closed-set corpus (Speaks & Jerger, 1965) in which listeners are asked to match presented sentences to a list of a possible 10 sentences. Top-down information in this case can very effectively constrain identification; only part of the sentence needs to be audible for identification to be successful. Small changes in audibility, therefore, can have large effects on intelligibility resulting in a steep slope. The IEEE corpus, on the other hand, is open set (Rothauser et al., 1969), as it consists of 720 sentences on different topics. Top-down information is far less constraining in this case. Although the context of the sentence may allow some top-down influence, speech identification will be much more heavily dependent on bottom-up information for these speech stimuli compared with the SSI, thus giving less improvement in intelligibility as SNR is increased and so a shallower psychometric function.

The CRM corpus is also a closed set, offering 32 response options. The survey demonstrated that despite this, the CRM corpus tended to give relatively shallow slopes (e.g., 3.7% per dB with a single speech masker). This may be partially explained by the fact that there are no contextual or semantic cues available in CRM sentences to aid in the identification of the keywords. The CRM keywords are likely less constrained by top-down information than the SSI corpus. Also, studies that used CRM sentences as targets also commonly used CRM sentences as maskers. This increased similarity between the target and masker, as described in the Slope Changes as a Consequence of Target/Masker Confusion section, may also explain the shallower than expected psychometric functions for this particular speech corpus when presented in a speech masker.

Conclusions

The slope of the psychometric function for masked speech varies greatly (mean, 7.5% per dB; range, 0–44% per dB). Understanding the factors affecting the slope of the psychometric function and the mechanisms that underlie these slope changes is important, as it gives a means of gauging the amount of perceptual benefit that can be expected given a specific change in SNR in a specific listening condition.

The survey of 885 psychometric functions has demonstrated that the type and number of speech maskers both had an effect on slope as did the choice of target corpus, its predictability, and its similarity to the masker. Three broad underlying mechanisms were outlined to explain why there is such a large variation across listening conditions, these mechanisms including slope changes as the result of amplitude modulations in the masker, confusion between the target and the masker, and the availability of top-down information. In particular, single speech maskers are likely to give particularly shallow slopes, as they contain amplitude modulations that offer extensive opportunities for glimpsing while still sharing acoustic and linguistic features that may become confused with the target speech.

The current survey has highlighted that the slope of the psychometric function, and therefore the amount of perpetual benefit that can be gained from an increase in SNR, is not fixed but instead varies greatly depending on both target and masker selection. These findings would suggest that care needs to be taken in selecting both target and masker stimuli for speech research with consideration made about the likely shape of the psychometric function, as well as the likely threshold. That the slope of the psychometric function can vary so much is particularly pertinent for listeners who struggle with speech-in-noise understanding and who rely on a hearing aid to provide improvement in speech audibility. The slope for these listeners will relate directly to the amount of benefit they might expect to receive from their hearing aid. The current study was unable to ascertain the direct effects that hearing impairment and age had on the slope of the psychometric function. These effects are an important direction for future research, as an understanding of them is crucial if we wish to quantify the amount of perceptual benefit a listener is likely to gain from any change in SNR offered by a hearing aid.

Notes

The date marked the end of the first author's PhD studentship during which time this work was carried out.

Modulated maskers included all maskers with temporally fluctuating amplitude, regardless of the type and spectral shape of modulation.

The 26 speech corpora were coded: AB Lists—Isophonemic Monosyllabic Word test (Boothroyd, 1968), ASL—Audio-visual Sentence Lists (MacLeod & Summerfield, 1990), BKB—Bamford-Kowal-Bench sentence lists (Bench, Kowal, & Bamford, 1979), CAT—Callsign Acquisition Test (Rao & Letowski, 2006), CCT—California Consonants Test (Owens & Schubert, 1977), CID sentences—Central Institute for the Deaf sentences (Silverman & Hirsh, 1955), CST—Connected Speech Test (Cox & Gilmore, 1987), CRM—The Coordinate Response Measure (Bolia, Nelson, Ericson, & Simpson, 2000), DANTALE II—Danish sentence test (Wagener et al., 2003), FAAF—The Four Alternative Auditory Feature tests (Foster & Haggard, 1987), Hagerman sentences—Swedish sentences (Hagerman, 1982), HINT—Hearing In Noise Test (Nilsson, Soli, & Sullivan, 1994), IEEE—IEEE sentences (Rothauser et al., 1969), LIST—Leuven Intelligibility Sentences Test (Van Wieringen & Wouters, 2008), Matrix Test (HearCom, 2009), MCDT—Multiple Choice Discrimination Test (Schultz & Schubert, 1969), MRT—Modified Rhyme Test (House et al., 1965), NU-6—Northwestern University Auditory Tests No. 6.(Tillman & Carhart, 1966), PB List—Phonetically balance words lists (Egan, 1948), Picture Identification Task (Wilson & Antablin, 1980), PSI Test—Pediatric Speech Intelligibility Test (Jerger et al., 1981), SPIN—Speech In Noise Test (Kalikow et al., 1977), SSI—Synthetic Sentence Identification Test (Speaks & Jerger, 1965), TMV—open-set sentences (Helfer & Freyman, 2009), TTI—The NSMRL tri-word test of intelligibility (Sergeant et al., 1979), W-22—Central Institute for the Deaf word lists (Benson et al., 1951).

Note that as fewer than 20 psychometric functions were found for the 16 remaining speech tests, the data for these have been combined and appear as “Other” in Tables 2 and 3.

The slopes of psychometric functions measured for mixed maskers (those with more than one category of masker) were excluded from this particular analysis.

Few studies have looked at the use of more than one noise masker; therefore, if all masker types were included, the increased masker conditions would be biased toward speech maskers.

Due the low number of slopes found for one speech masker, the number of speech maskers was not restricted in this case and includes all speech masker cases regardless of number of maskers.

Only cases where one masker was used have been included; other standard speech corpora have been excluded from this analysis due to small sample sizes with just one masker.

Cases where the masker or the target speech had been manipulated or processed in some way, for example, the fundamental frequency was shifted or the speech was vocoded, have been excluded, as these would affect the similarity between the target and masker voices.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The first author was funded by a PhD studentship from the Medical Research Council, which was hosted by the University of Strathclyde. The Scottish Section of IHR is supported by the Medical Research Council (grant number U135097131) and by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government.

References

- Acton W. I. (1970) Speech intelligibility in a background noise and noise-induced hearing loss. Ergonomics 13(5): 546–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbogast T. L., Mason C. R., Kidd G. (2002) The effect of spatial separation on informational and energetic masking of speech. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 112(5): 2086–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker J., Cooke M. (2007) Modelling speaker intelligibility in noise. Speech Communication 49(5): 402–417. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie R. C. (1989) Word recognition functions for CID W-22 test in multitalker noise for normally hearing and hearing impaired subjects. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 54: 20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie R. C., Barr T., Roup C. (1997) Normal and hearing-impaired word recognition scores for monosyllabic words in quiet and noise. British Journal of Audiology 31: 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie R. C., Clark N. (1982) Practice effects of a four-talker babble on the synthetic sentence identification test. Ear and Hearing 3(4): 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bench J., Kowal A., Bamford J. (1979) The BKB (Bamford-Kowal-Bench) sentence lists for partially-hearing children. British Journal of Audiology 13(3): 108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson R. W., Davis H., Harrison C. E., Hirsch I. J., Reynolds E. G., Silverman S. R. (1951) C.I.D. Auditory tests W-1 and W-2. Laryngoscope 61(8): 838–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J. G. W., Grant K. W. (2009) Auditory and auditory-visual intelligibility of speech in fluctuating maskers for normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 125(5): 3358–3372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best V., Gallun F. J., Mason C. R., Kidd G., Shinn-Cunningham B. G. (2010) The impact of hearing loss on the processing of simultaneous sentences. Ear and Hearing 31(2): 213–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj H. M., Verhulst S., Shaheen L., Liberman M. C., Shinn-Cunningham B. G. (2014) Cochlear neuropathy and the coding of supra-threshold sound. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience 26(8): 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya A., Zeng F. (2007) Companding to improve cochlear-implant speech recognition in speech-shaped noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 122(2): 1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blue-Terry M., Letowski T. (2011) Effects of white-noise on Callsign Acquisition Test and Modified Rhyme Test scores. Ergonomics 54(2): 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolia R., Nelson W., Ericson M., Simpson B. (2000) A speech corpus for multitalker communications research. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 107: 1065–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd A. (1968) Developments in speech audiometry. British Journal of Audiology 2(1): 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd A. (2008) The performance/intensity function: An underused resource. Ear and Hearing 29: 479–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd A., Nittrouer S. (1988) Mathematical treatment of context effects in phoneme and word recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 84(1): 101–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosman A. J., Smoorenburg G. F. (1995) Intelligibility of Dutch CVC syllables and sentences for listeners with normal hearing and with three types of hearing impairment. Audiology 34(5): 260–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronkhorst A. W., Bosman A. J., Smoorenburg G. F. (1993) A model for context effects in speech recognition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 93(1): 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S. (2001a) Informational and energetic masking effects in the perception of two simultaneous talkers. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 109: 1101–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S. (2001b) Evaluation of speech intelligibility with the coordinate response measure. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 109(5): 2276–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Chang P. S., Simpson B. D., Wang D. L. (2006) Isolating the energetic component of speech-on-speech masking with ideal time-frequency segregation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 120(6): 4007–4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Chang P. S., Simpson B. D., Wang D. L. (2009) Multitalker speech perception with ideal time-frequency segregation: Effects of voice characteristics and number of talkers. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 125(6): 4006–4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Darwin C. J., Arbogast T. L., Kidd G. (2005) Across-ear interference from parametrically degraded synthetic speech signals in dichotic cocktail-party listening task. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 117(1): 292–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Iyer N., Simpson B. D. (2006) Monaural speech segregation using synthetic speech signals. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 119(4): 2327–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Simpson B. D. (2002) Within-ear and across-ear interference in a cocktail-party listening task. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 112: 2958–2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Simpson B. D. (2004) Within-ear and across-ear interference in a dichotic cocktail party listening task: Effects of masker uncertainty. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 115(1): 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Simpson B. D. (2007) Effect of target-masker similarity on across-ear interference in a dichotic cocktail-party listening task. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 122(3): 1724–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Simpson B. D., Ericson M. A., Scott K. R. (2001) Informational and energetic masking effects in the perception of multiple simultaneous talkers. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 110(5): 2527–2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brungart D. S., Simpson B. D., Freyman R. L. (2005) Precedence-based speech segregation in a virtual auditory environment. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 118(5): 3241–3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G., Mizuseki K. (2014) The log-dynamic brain: How skewed distributions affect network operations. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 15(4): 264–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carhart R., Tillman T. W., Greetis E. S. (1969) Perceptual masking in multiple sound backgrounds. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 45(3): 694–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cienkowski K. M., Speaks C. (2000) Subjective vs. objective intelligibility of sentences in listeners with hearing loss. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 43: 1205–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke M. (2006) A glimpsing model of speech perception in noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 119(3): 1562–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. R., Cutts B. P. (1971) Speech discrimination in noise. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 14: 332–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. M., Gilmore C. (1987) Development of the Connected Speech Test (CST). Ear and Hearing 8: 119S–126S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig C. H. (1988) Effect of three conditions of predictability on word-recognition performance. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research 31: 588–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandell C. (1993) Speech recognition in noise by children with minimal degrees of sensorineural hearing loss. Ear & Hearing 14(3): 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H., Micheyl C. (2011) Psychometric functions for pure-tone frequency discrimination. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 130(1): 263–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhauer J. L., Doyle P. C., Lucks L. E. (1986) Effects of signal-to-noise ratio on the nonsense syllable test. Ear and Hearing 7(5): 323–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhauer J. L., Leppler J. G. (1979) Effects of 4 noise competitors on the California Consonant Test. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 44(3): 354–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. J., Brungart D. S., Simpson B. D. (2003) Effects of fundamental frequency and vocal-tract length changes on attention to one of two simultaneous talkers. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 114(5): 2913–2922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks D. D., Bell T. S., Rossman R. N., Kincaid G. E. (1986) Articulation index predictions of contextually dependent words. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 80(1): 82–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks D. D., Bower D. (1969) Masking effects of speech competing messages. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 12: 229–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks D. D., Morgan D. E., Dubno J. R. (1982) A procedure for quantifying the effects of noise on speech recognition. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 47(2): 114–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks D. D., Wilson R. H. (1969a) Binaural hearing of speech for aided and unaided conditions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 12(3): 650–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks D. D., Wilson R. H. (1969b) Effect of spatially separated sound sources on speech intelligibility. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 12(1): 5–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirks D. D., Wilson R. H., Bower D. R. (1969) Effect of pulsed masking on selected speech materials. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 46(4): 898–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drullman R. (1995) Speech intelligibility in noise: Relative contribution of speech elements above and below the noise level. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 98(3): 1796–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drullman R., Bronkhorst A. W. (2004) Speech perception and talker segregation: Effects of level, pitch and tactile support with multiple simultaneous talkers. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 116(5): 3090–3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drullman R., Festen J. M., Plomp R. (1994) Effect of reducing slow temporal modulations on speech reception. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 95(5): 2670–2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubno J. R., Ahlstrom J. B., Horwitz A. R. (2000) Use of context by young and aged adults with normal hearing. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 107(1): 538–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubno J. R., Horwitz A. R., Ahlstrom J. B. (2005) Word recognition in noise at higher-than-normal levels: Decreases in scores and increases in masking. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 118(2): 914–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duquesnoy A. J. (1983) Effect of single interfering noise or speech source upon the binaural sentence intelligibility of aged persons. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 74(3): 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan J. P. (1948) Articulation testing methods. Laryngoscope 58: 955–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan J. P., Carterette E., Thwing E. (1954) Factors affecting multichannel listening. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 26: 774–782. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. S., Dirks D. D., Bell T. S. (1995) Speech recognition in amplitude-modulated noise of listeners with normal and listeners with impaired hearing. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 38: 222–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]