Abstract

Look AHEAD was a randomized clinical trial designed to examine the long-term health effects of weight loss in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. The primary result was that the incidence of cardiovascular events over a median follow up of 9.6 years was not reduced in the intensive lifestyle group relative to the control group. This finding is discussed, with emphasis on its implications for design of clinical trials and clinical treatment of obese people with type 2 diabetes.

Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) was a randomized clinical trial funded by the National Institutes of Health that was designed to examine the long-term health effects of weight loss in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. The primary results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013 [1]. In this paper we will review the rationale for launching Look AHEAD, the methods involved, and some of the most important results. The primary goal will be to discuss the implications of Look AHEAD for future clinical trial design and clinical practice.

Rationale for Look AHEAD

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are major health problems, and both are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Although short-term weight loss has been shown to improve cardiovascular risk factors in these individuals, few studies have examined the long-term health consequences of intentional weight loss. Observational studies have raised concerns about possible adverse effects of weight loss. In studies of both adults with and without diabetes, those who lost the most weight often had increased, rather than decreased, risk of subsequent cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [2–4]. Moreover a review of six observational studies of weight loss in individuals with type 2 diabetes found no consistent effects [5], with some studies showing positive effects of weight loss, some showing negative effects, and some suggesting that the effect varied in different subgroups of the population. A major concern in these observational studies is the inability to distinguish voluntary weight loss from involuntary weight loss, which may represent weight loss due to illness. A 12-year observational study that examined specifically intentional weight loss in individuals with diabetes suggested positive effects, with the greatest benefit in those who lost 20–29 pounds (9 – 13 Kg) [6].

The lack of long-term randomized trial data showing beneficial effects of weight loss in obese individuals with diabetes, coupled with the inconsistent and often concerning results of observational studies, led the National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to host a workshop to determine the feasibility of a randomized trial to examine the long-term impact of weight loss on major health problems and mortality. This workshop concluded that such a trial was warranted and feasible. The Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Study (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT0017953) was designed to compare the long-term health effects of intensive lifestyle intervention aimed at weight loss compared to a control group in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes.

Selection of Primary Outcome Measures and Sample Size calculation

Originally the primary hypothesis was that the lifestyle intervention would reduce the incidence of a composite endpoint including fatal myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke, non-fatal MI, or non-fatal stroke, and the maximal follow-up was 11.5 years. During the initial years of the trial, the event rate for the primary outcome in the control group was lower than expected; thus the primary outcome was modified to include hospitalized angina, and the planned follow-up was extended to a maximum of 13.5 years. The deliberations that led to this change have been described in detail [7]. Three secondary composite cardiovascular outcomes were also examined: (1) death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI or stroke; (2) death from any cause, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for angina; and (3) death from any cause, MI, stroke, or hospitalization for angina, coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary intervention, hospitalization for heart failure, or peripheral vascular disease.

A sample of 5000 participants was selected to provide >80% power to detect an 18% difference between groups in the rate of major cardiovascular events, with a two-sided alpha of 0.05, a primary outcome rate of 2% per year in the control group, and a maximum planned follow-up of 13.5 years.

Methods

The methods for Look AHEAD have been described in several prior publications [8–10]. Only key aspects are described in this manuscript.

Participants

Look AHEAD was conducted in 16 clinical sites distributed across the United States and recruited 5,145 overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes. All participants were required to be aged 45 – 76 years, BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2 (≥27 kg/m2 if on insulin), HbA1c ≤ 11% (97 mmol/mol), systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤ 160 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≤ 100 mmHg, and triglycerides ≤ 600 mg/dl (6.8 mmol/L). Individuals could be using any type of medication to control their diabetes, but the sample was limited to < 30% on insulin because of concerns about producing weight loss in these individuals. Participants with and without a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD) were eligible in order to increase the generalizability of the results. Participants were required to have their own health care provider (who remained responsible for any changes in medications) and to complete a maximal exercise test successfully to ensure the safety of the physical activity component of the intervention.

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned to an Intensive Lifestyle Intervention or Diabetes Support and Education, the control condition. The Intensive Lifestyle Intervention follows closely on the intervention used in Diabetes Prevention Program [11]. It was designed to achieve and maintain at least 7% weight loss [9, 12]. This weight loss was achieved through caloric restriction (goals of 1200 – 1800 kcal/day), use of meal replacement products, and increased physical activity (goal of 175 minutes/week of moderate intensity physical activity). Each of these components was based on empirical evidence [9, 12]. Participants self-monitored their diet and physical activity throughout the program and were taught behavioral strategies. To teach this information and provide ongoing support, the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention program included frequent therapist contact with a combination of group and individual sessions. Participants were seen weekly for the first 6 months, 3 times/month for months 7–12, and then with decreasing frequency over time. However, active intervention was maintained throughout the full duration of the trial.

The Diabetes Support and Education group attended fewer sessions (3/year for years 1 – 4 and then 1/year) that focused on education about diet and physical activity, and provided social support, but did not include any of the behavioral strategies.

Assessments

All participants attended annual visits where basic measures of weight and CVD risk factors were obtained and questionnaires were completed. All prescription medications were brought to these visits and recorded. Assessments were done by staff blinded to study-group assignment. Maximal stress tests were performed at baseline and submaximal tests at years 1 and 4 on the full cohort and at year 2 on a subset. Several other measures were obtained on only subgroups: physical activity was measured by both the Paffenbarger activity questionnaire and objectively by accelerometer on 50% of subjects at baseline, 1, and 4 years (only Paffenbarger at year 8); Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was obtained at baseline, 1, 4, and 8 years on a subset, and food frequency was measured at baseline, 1, and 4 years on the first 50% of participants.

Occurrence of potential primary cardiovascular outcomes was ascertained by interview at the annual visit and at 6 month phone calls by blinded staff. Hospital and other records were then reviewed for potential events, with adjudication of all possible outcomes. Costs of intervention and medical care were examined prospectively throughout the trial.

Results

The intervention component of Look AHEAD was stopped early (Sept 14, 2012) by the National Institutes of Health sponsors. This decision was based on the fact that the probability of observing a significant difference between Intensive Lifestyle Intervention and Diabetes Support and Education at the end of the planned follow-up was estimated to be 1% [1]. Thus, the study was considered to have answered the primary question it was designed to address. At the time the intervention was stopped, participants had completed 9–11 years of follow-up (median=9.6 years), and less than 4% of all participants had been lost to follow-up.

Weight loss, Fitness, and CVD Risk Factors

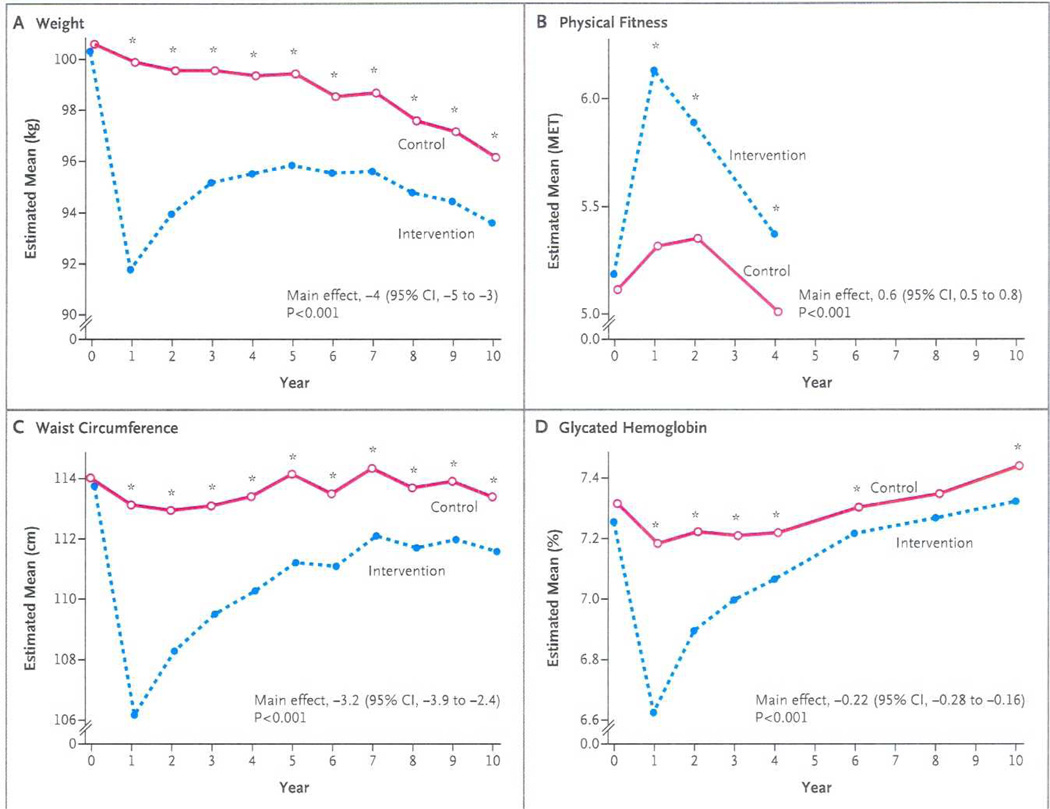

As shown in Figure 1, the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention produced significantly greater weight losses than Diabetes Support and Education at all time points. The difference was greatest at 1 year, when the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group had lost on average 8.6% of their body weight compared to 0.7% in the Diabetes Support and Education group. When the study ended, the mean weight loss from baseline was 6.0% in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group and 3.5% in the control group. The Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group also had greater improvements in fitness at years 1, 2, and 4 (the last time at which this measure was completed). The pattern of improvements in many of the risk factors (HbA1c, SBP, DBP, triglycerides, HDL-C) tended to parallel the weight losses, with the greatest benefit of Intensive Lifestyle Intervention relative to Diabetes Support and Education seen at Year 1, with gradually decreasing relative benefits over time (see Figure 1 for HbA1c as an example). However, averaged over the years of the trial, Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants had lower HbA1c, SBP, and HDL-C than Diabetes Support and Education participants. Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants were also less likely to be started on insulin or hypertension medications than were Diabetes Support and Education participants. However, in contrast to the other risk factors, the Diabetes Support and Education group showed greater improvements in LDL-C over the course of the trial. Although this difference in LDL-C was significant, it was modest (a mean difference of 1.6 mg/dl) and was related to the greater use of statins in the Diabetes Support and Education group than in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group.

Figure 1.

Changes in Weight, Physical Fitness, Waist Circumference, and Glycated Hemoglobin Levels during 10 Years of Follow-up.

“From Wing, R.R., et al., Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(2): p. 145–54. Copyright © 2013 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Primary Outcomes

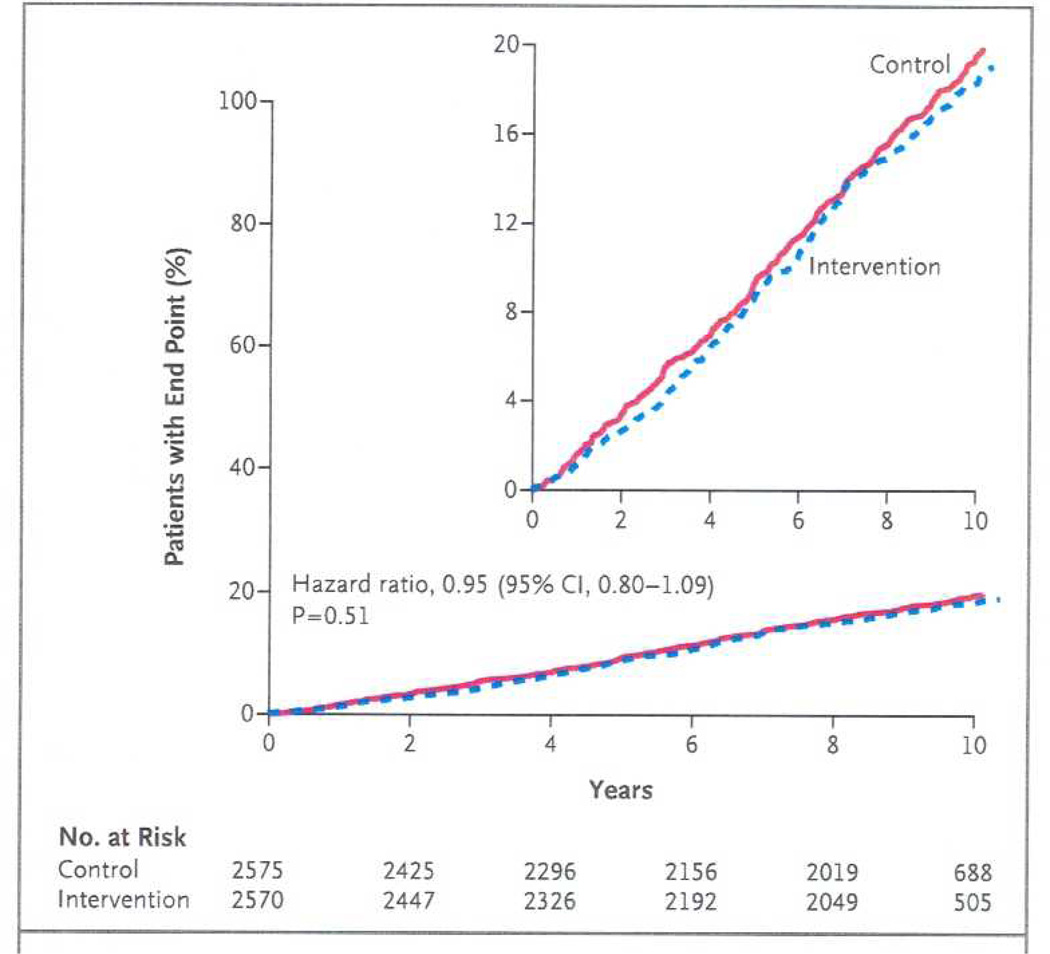

Figure 2 shows the incidence of the primary outcome in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group compared to Diabetes Support and Education group. The primary outcome occurred in 403 participants in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group and 418 in the Diabetes Support and Education group (1.83 and 1.92 events per 100 person-years, respectively). The hazard ratio in the intervention group was 0.95 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.09, p=0.51). There were also no significant differences between groups for any of the composite secondary outcomes or the individual cardiovascular events. Thus, there was no evidence that the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention reduced the risk of cardiovascular events. Moreover, the 95% confidence interval for the primary outcome excluded the benefit of 18% or more that was targeted in the trial design, suggesting that this lack of significant differences between groups was not due to insufficient statistical power.

Figure 2.

Cumulative Hazard Curves for the Primary Composite End Point.

“From Wing, R.R., et al., Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(2): p. 145–54. Copyright © 2013 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Discussion of Trial Design

There has been much discussion about the results of Look AHEAD. Most of this has focused on efforts to explain why the intervention was not successful in reducing CVD events. Given that the study was successful in achieving its recruitment goals, that Intensive Lifestyle Intervention produced significantly greater weight losses than Diabetes Support and Education throughout the entire trial, and that over 96% of randomized participants were retained in the trial, we feel that the trial was conducted as planned and that the results, although perhaps unexpected, are valid. These findings provide important data about the way in which lifestyle intervention does and does not benefit individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Implications for Trial Design

Below we consider the concerns that have been raised about the design of the trial. Although we remain confident that we made appropriate decisions in designing this study, we consider below some of these decisions and their implications for conclusions that can be drawn from the trial.

Design decisions related to participants

Concerns have been raised about the study population; some feel that the participants were too healthy to see benefits, while others argue that their disease was too advanced to see benefits. We stress that we recruited the population specified in our protocol and that we had sufficient number of events (power) to detect clinically meaningful effects. However, several decisions made in selecting the population to study in this trial may have affected our outcomes and clearly affect the ability to generalize the findings to other patient groups. First, we chose to study individuals with type 2 diabetes. On average, these participants had diagnosed diabetes for over 5 years. It is possible that different results would be obtained in individuals who did not have diabetes, but the sample size required for such a trial would be substantial. Second, our participants volunteered for a study of weight loss and thus were likely motivated to achieve this goal. In addition, our participants were required to complete a maximal stress test successfully at baseline to ensure safety of the intervention: 638 (11%) of the 5783 participants who had met all other eligibility criteria for the trial were excluded based on their stress test results [13]. Excluding these individuals led to a “healthier” study group and may have reduced the number of CVD events that we observed. In designing the trial, we decided to include participants with a history of CVD both to increase the generalizability of the findings and also to maximize the expected event rate; 14% of the randomized participants had a history of prior CVD. Although a small proportion of subjects in the cohort, the subgroup of participants with CVD accounted for the majority of CVD events seen in Look AHEAD. Moreover, our results suggested that participants with and without a history of CVD may have responded differently to the intervention. Although the interaction with CVD history was not significant, the p-value for the interaction for the primary outcome was p=0.06, with a hazard ratio of 0.86 (0.72–1.02) in the group that did not have CVD history at baseline and 1.13 (0.90–1.42) in those with a history of CVD [1].

Design decisions regarding medical care

Another design decision was to require that all participants have their own health care provider who remained responsible for any changes in medications, with the exception of initial changes in glucose-lowering medication to reduce the risk of hypoglycemia in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group. Having physicians remain in control of all aspects of medical care was deemed essential for recruiting participants, allowing medications to be adjusted as they would in routine care, and separating weight loss intervention (provided by Look AHEAD) from medical care (provided by health care providers). Providing all medical care and medications would have made the trial prohibitively expensive, may have adversely affected recruitment, or altered the composition of the recruited cohort. In addition, we provided annual reports to each physician indicating their participants’ current level of HbA1c, lipids, weight, and blood pressure, and comparing these to recommended levels. This information may have encouraged physicians to increase their efforts to achieve these recommended goals. Consequently, the intensification of medical management of cardiovascular risk factors in both study groups by their own health care providers, along with the trial design that provided educational sessions to the control group, may have lessened the differences between Intensive Lifestyle Intervention and Diabetes Support and Education.

Design decisions regarding the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention and Diabetes Support and Education interventions

The design of the intervention was based on the goal of the trial—to test the effects of weight loss achieved through lifestyle intervention on cardiovascular outcomes. Thus, the study sought to optimize the weight losses achieved with these approaches in order to provide a robust test of the study hypotheses. Look AHEAD was not designed to test bariatric surgery, and we know of no studies comparing cardiovascular outcomes in patients randomly assigned to lifestyle intervention or bariatric surgery. In addition, Look AHEAD was not designed to tease apart the benefits of weight loss versus physical activity nor to be low in cost and directly translatable to community settings. The Intensive Lifestyle Intervention provided opportunities for frequent ongoing contact with both the case-managers and the other participants since continued contact has been clearly associated with improved long-term outcomes [14]. Moreover, given the extensive data showing that the combination of diet plus physical activity is most effective for long-term weight control [14], the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention included both components. Similarly, the intervention focused on caloric restriction and was not designed to compare dietary interventions of different macronutrient distributions. Participants were encouraged to consume <30% of calories from fat (<10% from saturated fat) and a minimum of 15% of calories from protein, recommendations that are consistent with America Heart Association and American Diabetes Association guidelines, and have been used in many prior weight loss trials. Healthy eating patterns were stressed throughout the program. Meal replacement products were provided free to Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants; their inclusion in the trial was based on prior studies showing increased weight loss with portion-controlled diets[15]. We feel that each of these decisions contributed to the success of our intervention in producing outstanding initial and long-term weight loss outcomes.

Implications for clinical care

What are the implications of Look AHEAD for clinical treatment of overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes? We feel that one of the most important messages from this study is that individuals with diabetes can successfully lose weight and maintain it. On average, Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants lost 8.6% of their body weight at 1 year and maintained a weight loss of 6% at study end. Although Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants achieved their greatest weight loss at 1 year followed by some weight regain, our results suggest that the rate of regain was greatest between years 1 and 2, and then slowed over time and that significant weight losses, relative to Diabetes Support and Education, were maintained across the entire study period (average of 9.6 years of follow-up). These are the longest weight loss results of which we are aware.

A recent publication provides more detailed weight loss information in the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention and Diabetes Support and Education group at year 8, at the final assessment that included all participants before the intervention was stopped [16]. We found that over 50% of Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants had maintained a 5% weight loss at year 8 (36% with Diabetes Support and Education), and 27% had lost >10% (vs 17% with Diabetes Support and Education). Men and women had comparable weight losses at year 8. Likewise, all racial and ethnic groups achieved similar long term weight loss. Look AHEAD also found that individuals using insulin were indeed able to lose weight, with weight losses that were not significantly different from those not on insulin [17], that severely obese individuals benefitted as well as less overweight individuals [18], and that the oldest participants (age 66–76 years) had the best weight losses and adherence to the program [17, 19]. Look AHEAD confirmed previous studies in showing that adherence to treatment, defined in terms of attendance, use of meal replacement products as a marker of adherence to the diet, or self-reported physical activity, was related to both short- and long-term weight loss outcomes.

A second important clinical message from Look AHEAD is that there are many important health benefits of lifestyle intervention, although reduction in CVD outcomes may not be one of these benefits. We have already published results showing other very important clinical benefits of this intervention. Of particular note is the fact that Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants were more likely than those in the Diabetes Support and Education group to experience a complete or partial remission of their diabetes (i.e., were able to revert to prediabetes or normoglycemia without using hypoglycemic medication) [20]. At 1 year 11.5% of Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants, compared to 2.0% with Diabetes Support and Education, experienced remission; at year 4, remission was seen in 7.3% of Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants compared to 1.5% with Diabetes Support and Education (p<.001 for each) . Intensive Lifestyle Intervention also decreased the risk of developing kidney disease and self-reported diabetic eye disease, suggesting that the benefits may be seen more on microvascular complications than on macrovascular complications (Knowler, presentation at the American Diabetes Association Annual Meeting, 2013). The lifestyle intervention also reduced medical care costs, including hospital care costs and medication costs, relative to Diabetes Support and Education [21]. At the start of the trial, 87% of the 306 participants examined, had polysomnography documented sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea (AHI) index > or equal to 5) [22]. Within this group, those participants who were randomized to Intensive Lifestyle Intervention had greater improvements in the AHI scores at both 1 year and 4 years than did those in the Diabetes Support and Education group. A substantial improvement in AHI was maintained at year 4 even though Intensive Lifestyle Intervention participants experienced some weight regain [23].

Look AHEAD has also published findings suggesting that Intensive Lifestyle Intervention may decrease other adverse consequences of aging in this population. Although mobility problems increased over time in both Intensive Lifestyle Intervention and Diabetes Support and Education groups in Look AHEAD, likely due to aging, the Intensive Lifestyle Intervention group had a relative risk reduction of 48% for loss of mobility between baseline and year 4 as compared to the Diabetes Support and Education group [24]. Both weight loss and improved fitness were significant mediators of this effect [24]. Intensive Lifestyle Intervention also led to significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms than Diabetes Support and Education [25], greater improvements in urinary incontinence for both men [26] and women [27], and less worsening with age of sexual dysfunction [28] and erectile dysfunction [29].

Thus, from a clinical perspective, there are many important reasons to encourage overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes to lose weight to improve their health. Although Look AHEAD did not show reductions in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality relative to a control group given diabetes support and education, the Look AHEAD trial provides important evidence that individuals with diabetes can lose weight and maintain it long-term and that even modest weight losses can have important health benefits.

Appendix

Look AHEAD Research Group at End of Intervention

Updated 03/25/2013

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins University Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS1; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH1 (Co-Principal Investigators); Lee Swartz2; Jeanne Charleston, RN3; Lawrence Cheskin, MD3; Kerry Stewart, EdD3; Richard Rubin, PhD3; Jean Arceci, RN; Susanne Danus; David Bolen; Danielle Diggins; Sara Evans; Mia Johnson; Joyce Lambert; Sarah Longenecker; Kathy Michalski, RD; Dawn Jiggetts; Chanchai Sapun; Maria Sowers; Kathy Tyler

Pennington Biomedical Research Center George A. Bray, MD1; Allison Strate, RN2; Frank L. Greenway, MD3; Donna H. Ryan, MD3; Donald Williamson, PhD3; Timothy Church, MD3 ; Catherine Champagne, PhD, RD; Valerie Myers, PhD; Jennifer Arceneaux, RN; Kristi Rau; Michelle Begnaud, LDN, RD, CDE; Barbara Cerniauskas, LDN, RD, CDE; Crystal Duncan, LPN; Helen Guay, LDN, LPC, RD; Carolyn Johnson, LPN, Lisa Jones; Kim Landry; Missy Lingle; Jennifer Perault; Cindy Puckett; Marisa Smith; Lauren Cox; Monica Lockett, LPN

The University of Alabama at Birmingham Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH1; Sheikilya Thomas, MPH2; Monika Safford, MD3; Stephen Glasser, MD3; Vicki DiLillo, PhD3; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Amy Dobelstein; Sara Hannum, MA; Anne Hubbell, MS; Jane King, MLT; DeLavallade Lee; Andre Morgan; L. Christie Oden; Janet Wallace, MS; Cathy Roche, PhD,RN, BSN; Jackie Roche; Janet Turman

Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital. David M. Nathan, MD1; Enrico Cagliero, MD3; Kathryn Hayward, MD3; Heather Turgeon, RN, BS, CDE2; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD2; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD3; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD3; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Theresa Michel, DPT, DSc, CCS; Mary Larkin, RN; Christine Stevens, RN

Joslin Diabetes Center: Edward S. Horton, MD1; Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE2; Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD3; A. Enrique Caballero, MD3; Sarah Bain, BS;

Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Barbara Fargnoli, MS,RD; Jeanne Spellman, BS, RD; Kari Galuski, RN; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Lori Lambert, MS, RD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center: George Blackburn, MD, PhD1; Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc3; Ann McNamara, RN; Kristina Spellman, RD

University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus James O. Hill, PhD1; Marsha Miller, MS RD2; Holly Wyatt, MD3 , Brent Van Dorsten, PhD3; Judith Regensteiner, PhD3; Debbie Bochert; Ligia Coelho, BS; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; Susan Green; April Hamilton, BS, CCRC; Jere Hamilton, BA; Eugene Leshchinskiy; Loretta Rome, TRS; Terra Thompson, BA; Kirstie Craul, RD,CDE; Cecilia Wang, MD

Baylor College of Medicine John P. Foreyt, PhD1; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD2; Molly Gee, MEd, RD2; Henry Pownall, PhD3; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MBBS3; Chu-Huang Chen, MD, PhD3; Peter Jones, MD3; Michele Burrington, RD, RN; Allyson Clark Gardner,MS, RD; Sharon Griggs; Michelle Hamilton; Veronica Holley; Sarah Lee; Sarah Lane Liscum, RN, MPH; Susan Cantu-Lumbreras; Julieta Palencia, RN; Jennifer Schmidt; Jayne Thomas, RD; Carolyn White

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

University of Tennessee East. Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH1; Carolyn Gresham, RN2; Mace Coday, PhD; Lisa Jones, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN; J. Lee Taylor, MEd, MBA; Beate Griffin, RN; Donna Valenski

University of Tennessee Downtown. Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD1; Ebenezer Nyenwe, MD3; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN2; Moana Mosby, RN; Amy Brewer, MS, RD,LDN; Debra Clark, LPN; Andrea Crisler, MT; Gracie Cunningham; Debra Force, MS, RD, LDN; Donna Green, RN; Robert Kores, PhD; Renate Rosenthal, PhD; Elizabeth Smith, MS, RD, LDN

University of Minnesota Robert W. Jeffery, PhD1; Tricia Skarphol, MA2; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP2; John P. Bantle, MD3; J. Bruce Redmon, MD3; Richard S. Crow, MD3; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; Carolyne Campbell; Lisa Hoelscher, MPH, RD, CHES; Melanie Jaeb, MPH, RD; LaDonna James; Patti Laqua, BS, RD; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Therese Ockenden, RN; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh, CHES; Ann D. Tucker, BA; Mary Susan Voeller, BA; Cara Walcheck, BS,RD

St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD1; Jennifer Patricio, MS2; Carmen Pal, MD3; Lynn Allen, MD;Janet Crane, MA, RD, CDN; Lolline Chong, BS, RD; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN; Michelle Horowitz, MS, RD

University of Pennsylvania Thomas A. Wadden, PhD 1; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE 2; Robert I. Berkowitz, MD 3; Seth Braunstein, MD, PhD 3 ; Gary Foster, PhD 3; Henry Glick, PhD 3; Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH 3; Stanley S. Schwartz, MD 3 ; Yuliis Bell, BA; Raymond Carvajal, PsyD; Helen Chomentowski; Renee Davenport; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Lucy Faulconbridge, PhD; Louise Hesson, MSN, CRNP; Nayyar Iqbal, MD; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Monica Mullen, RD, MPH

University of Pittsburgh John M. Jakicic, PhD1; David E. Kelley, MD1; Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE2; Lewis H. Kuller, MD, DrPH3; Andrea Kriska, PhD3; Amy D. Rickman, PhD, RD, LDN3; Lin Ewing, PhD, RN3; Mary Korytkowski, MD3; Daniel Edmundowicz, MD3; Rose Salata, MD3; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Tammy DeBruce; Barbara Elnyczky; David O. Garcia, MS; Patricia H. Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Susan Harrier, BS; Dianne Heidingsfelder, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Diane Ives, MPH; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Lisa Martich, MS, RD; Tracey Y. Murray, BS; Karen Quirin; Joan R. Ritchea; Susan Copelli, BS, CTR

The Miriam Hospital/Brown Medical School Rena R. Wing, PhD1; Renee Bright, MS2; Vincent Pera, MD3; John Jakicic, PhD3; Deborah Tate, PhD3; Amy Gorin, PhD3; Kara Gallagher, PhD3; Amy Bach, PhD; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Tatum Charron, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Lisa Cronkite, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Maureen Daly, RN; Caitlin Egan, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Linda Foss, MPH; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Don Kieffer, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; JP Massaro, BS; Tammy Monk, MS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Deborah Robles; Jane Tavares, BS

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Steven M. Haffner, MD1; Helen P. Hazuda, PhD1; Maria G. Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE2; Carlos Lorenzo, MD3; Charles F. Coleman, MS, RD; Domingo Granado, RN; Kathy Hathaway, MS, RD; Juan Carlos Isaac, RC, BSN; Nora Ramirez, RN, BSN

VA Puget Sound Health Care System / University of Washington Steven E. Kahn, MB, ChB1; Anne Murillo, BS2; Robert Knopp, MD3; Edward Lipkin, MD, PhD3; Dace Trence, MD3; Elaine Tsai, MD3; Basma Fattaleh, BA; Diane Greenberg, PhD; Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE; Ivy Morgan-Taggart; Betty Ann Richmond, MEd; Jolanta Socha, BS; April Thomas, MPH, RD; Alan Wesley, BA; Diane Wheeler, RD, CDE

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH1; Paula Bolin, RN, MC2; Tina Killean, BS2; Cathy Manus, LPN3; Jonathan Krakoff, MD3; Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH3; Sara Michaels, MD3; Paul Bloomquist, MD3; Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP3; Bernadita Fallis RN, RHIT, CCS; Diane F. Hollowbreast; Ruby Johnson; Maria Meacham, BSN, RN, CDE; Christina Morris, BA; Julie Nelson, RD; Carol Percy, RN; Patricia Poorthunder; Sandra Sangster; Leigh A. Shovestull, RD, CDE; Miranda Smart; Janelia Smiley; Teddy Thomas, BS; Katie Toledo, MS, LPC

University of Southern California Anne Peters, MD1; Siran Ghazarian, MD2; Elizabeth Beale, MD3; Kati Konersman, RD, CDE; Brenda Quintero-Varela; Edgar Ramirez; Gabriela Rios, RD; Gabriela Rodriguez, MA; Valerie Ruelas MSW, LCSW; Sara Serafin-Dokhan; Martha Walker, RD

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University Mark A. Espeland, PhD1; Judy L. Bahnson, BA, CCRP3; Lynne E. Wagenknecht, DrPH3; David Reboussin, PhD3; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD3; Alain G. Bertoni, MD, MPH3; Wei Lang, PhD3; Michael S. Lawlor, PhD3; David Lefkowitz, MD3; Gary D. Miller, PhD3; Patrick S. Reynolds, MD3; Paul M. Ribisl, PhD3; Mara Vitolins, DrPH3; Daniel Beavers, PhD3; Haiying Chen, PhD, MM3; Dalane Kitzman, MD3; Delia S. West, PhD3; Lawrence M. Friedman, MD3; Ron Prineas, MD3; Tandaw Samdarshi, MD3;Kathy M. Dotson, BA2; Amelia Hodges, BS, CCRP2; Dominique Limprevil-Divers, MA, MEd2; Karen Wall, AAS2; Carrie C. Williams, MA, CCRP2; Andrea Anderson, MS; Jerry M. Barnes, MA; Mary Barr; Tara D. Beckner; Cralen Davis, MS; Thania Del Valle-Fagan, MD; Tamika Earl, Melanie Franks, BBA; Candace Goode; Jason Griffin, BS; Lea Harvin, BS; Mary A. Hontz, BA; Sarah A. Gaussoin, MS; Don G. Hire, BS; Patricia Hogan, MS; Mark King, BS; Kathy Lane, BS; Rebecca H. Neiberg, MS; Julia T. Rushing, MS; Valery Effoe Sammah; Michael P. Walkup, MS; Terri Windham

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco Michael Nevitt, PhD1; Ann Schwartz, PhD2; John Shepherd, PhD3; Michaela Rahorst; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA; Susan Ewing, MS; Cynthia Hayashi; Jason Maeda, MPH

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD1; Jessica Hurting2;

John J. Albers, PhD3 Vinod Gaur, PhD4

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Elsayed Z. Soliman MD, MSc, MS1; Charles Campbell 2; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD3; Mary Barr; Susan Hensley; Julie Hu; Lisa Keasler; Yabing Li, MD

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities

Elizabeth J Mayer-Davis, PhD1; Robert Moran, PhD1

Hall-Foushee Communications, Inc.

Richard Foushee, PhD; Nancy J. Hall, MA

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Mary Evans, PhD; Barbara Harrison, MS; Van S. Hubbard, MD, PhD; Susan Z. Yanovski, MD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Peter Kaufman, PhD, FABMR; Mario Stylianou, PhD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Edward W. Gregg, PhD; Ping Zhang, PhD

Funding and Support

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health; and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153) and NIH grant (DK 046204); the VA Puget Sound Health Care System Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs; and the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346).

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST® of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

Some of the information contained herein was derived from data provided by the Bureau of Vital Statistics, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

1Principal Investigator

2Program Coordinator

3Co-Investigator

All other Look AHEAD staffs are listed alphabetically by site.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest details: Dr. Wing wrote this manuscript on behalf of Look AHEAD. The findings discussed in this manuscript are due to the efforts of the Look AHEAD principal investigators in the design, conduct, and analysis of Look AHEAD.

Authorship details: None

References

- 1.Wing RR, et al. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins M, et al. Benefits and adverse effects of weight loss. Observations from the Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 Pt 2):758–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pamuk ER, et al. Weight loss and subsequent death in a cohort of U.S. adults. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 Pt 2):744–748. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andres R, Muller DC, Sorkin JD. Long-term effects of change in body weight on all-cause mortality. A review. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 Pt 2):737–743. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson DF. Weight loss and mortality in persons with type-2 diabetes mellitus: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1998;106(Suppl 2):14–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1212031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williamson DF, et al. Intentional weight loss and mortality among overweight individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(10):1499–1504. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.10.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brancati FL, et al. Midcourse correction to a clinical trial when the event rate is underestimated: the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Study. Clin Trials. 2012;9(1):113–124. doi: 10.1177/1740774511432726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray G, et al. Baseline characteristics of the randomised cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006;3(3):202–215. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Look AHEAD Research Group. Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes: Design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Look AHEAD Research Group. The development and description of the diabetes support and education (comparison group) intervention for the Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD)Trial. Clin Trials. 2011;8(3):320–329. doi: 10.1177/1740774511405858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knowler WC, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD study: A description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(5):737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis JM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of abnormal cardiovascular responses to exercise testing among individuals with type 2 diabetes: the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:901–907. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen MD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2013 doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ditschuneit HH, Flechtner-Mors M. Value of structured meals for weight management: risk factors and long-term weight maintenance. Obesity Research. 2001;9(Suppl 4):284S–289S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Look AHEAD Research Group. Eight-year weight losses with an intensive lifestyle intervention: the look AHEAD study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22(1):5–13. doi: 10.1002/oby.20662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadden TA, et al. Four-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with long-term success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(10):1987–1998. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unick JL, et al. The long-term effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in severely obese individuals. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.10.010. 242 e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espeland MA, et al. Intensive weight loss intervention in older individuals: results from the Action for Health in Diabetes Type 2 diabetes mellitus trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):912–922. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregg EW, et al. Association of an intensive lifestyle intervention with remission of type 2 diabetes. Jama. 2012;308(23):2489–2496. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.67929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Look AHEAD Research Group. Impact of an intensive lifestyle intervention on use and cost of medical services among overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: the Action for Health in Diabetes. Diabetes Care. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0093. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster GD, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1017–1019. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuna ST, et al. Long-term effect of weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea severity in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Sleep. 2013;36(5):641A–649A. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rejeski WJ, et al. Lifestyle change and mobility in obese adults with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(13):1209–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Look AHEAD Research Group. Impact of Intensive Lifestyle Intervention on Depression and Health-related Quality of Life in Type 2 Diabetes: The Look AHEAD Trial. Diabetes Care. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1928. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Breyer BN, et al. Intensive lifestyle intervention reduces urinary incontinence in overweight/obese men with type 2 diabetes: Results from the Look AHEAD trial. J Urol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phelan S, et al. Weight loss prevents urinary incontinence in women with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD trial. J Urol. 2012;187(3):939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wing RR, et al. Effect of Intensive Lifestyle Intervention on Sexual Dysfunction in Women With Type 2 Diabetes: Results from an ancillary Look AHEAD study. Diabetes Care. 2013 doi: 10.2337/dc13-0315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen RC, et al. Erectile dysfunction in type 2 diabetic men: relationship to exercise fitness and cardiovascular risk factors in the Look AHEAD trial. J Sex Med. 2009;6(5):1414–1422. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]