Abstract

Study Objective

To develop and validate a predictive model for glucose change and risk for new-onset impaired fasting glucose in hypertensive participants following treatment with atenolol or hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ).

Design

Randomized multicenter clinical trial.

Patients

A total of 735 white or African-American men and women with uncomplicated hypertension.

Measurements and Main Results

Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses (PEAR) is a randomized clinical trial to assess the genetic and nongenetic predictors of blood pressure response and adverse metabolic effects following treatment with atenolol or HCTZ. To develop and validate predictive models for glucose change, PEAR participants were randomly divided into a derivation cohort of 367 and a validation cohort of 368. Linear and logistic regression modeling were used to build models of drug-associated glucose change and impaired fasting glucose (IFG), respectively, in the derivation cohorts. These models were then evaluated in the validation cohorts. For glucose change after atenolol or HCTZ treatment, baseline glucose was a significant (p<0.0001) predictor, explaining 13% of the variability in glucose change after atenolol and 12% of the variability in glucose change after HCTZ. Baseline glucose was also the strongest and most consistent predictor (p<0.0001) for development of IFG after atenolol or HCTZ monotherapy. The area under the receiver operating curve was 0.77 for IFG after atenolol and 0.71 after HCTZ treatment, respectively.

Conclusion

Baseline glucose is the primary predictor of atenolol or HCTZ-associated glucose increase and development of IFG after treatment with either drug.

Keywords: β-Blockers, thiazide diuretics, hyperglycemia, atenolol, hydrochlorothiazide, impaired fasting glucose

The hyperglycemia associated with the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive drug classes is of growing concern to the medical community. It is well documented that β-blockers and thiazide diuretics cause adverse metabolic effects, and large-scale studies and meta-analyses provide compelling data indicating that β-blockers and thiazide diuretics increase the risk of diabetes.1–5

The ability to discern which participants are at greatest risk for hyperglycemia associated with β-blockers and thiazide diuretics or the development of diabetes would be valuable to clinicians4,6–9. Previous studies found that African ancestry, higher body mass index, left ventricular hypertrophy, higher follow-up systolic blood pressure, elevated baseline glucose, uric acid, female sex, and age are associated with the development of diabetes after long-term β-blocker and/or thiazide diuretic therapy. 3, 4, 10, 11 One study found that African ancestry, lower baseline glucose, and urinary sodium excretion were significant predictors for change in glucose after hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) monotherapy.12 To date, no studies have evaluated predictors for glucose change associated with β-blockers.

Given that hyperglycemia and diabetes associated with the use of thiazide diuretics and β-blockers may offset the clinical benefit of these two drug classes,10, 13–15 it is important to identify the clinical characteristics that increase risk. If such factors could be identified, they might be useful to guide selection of antihypertensive therapy. Therefore, the goal of the current study was to determine the clinical characteristics associated with change in glucose and impaired fasting glucose (IFG) following treatment with atenolol or HCTZ.

Research Design and Methods

Patient Population and Intervention

Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses (PEAR; NCT00246519) was a prospective, open-label, multicenter, randomized study of atenolol and HCTZ, taken alone followed by combination, to determine the genetic and nongenetic predictors of antihypertensive and adverse metabolic responses. Details of the PEAR study design were described previously. Briefly, enrollment of hypertensive participants occurred at the University of Florida (Gainesville, FL), Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN), and Emory University (Atlanta, GA). Eligibility criteria included male or female participants with mild to moderate hypertension (newly diagnosed, untreated, or known hypertension currently treated with one or two antihypertensive drugs, with average home diastolic blood pressure higher than 85 mm Hg and an average office diastolic blood pressure higher than 90 mm Hg) between the ages of 17 and 65, of any race or ethnicity. Participants treated with three or more antihypertensives were excluded from this study. The detailed list of exclusion criteria were described previously.16 Participants treated with one or two antihypertensive medications at study entry had their medications withdrawn. Participants were required to be free of antihypertensives for a minimum period of 18 days, with a preferred washout of at least 4 weeks, to give sufficient time for blood pressure and biochemical values to return to pre-treatment levels. The institutional review boards at all study sites approved the study protocol, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Baseline studies after washout included collection of home, office, and ambulatory blood pressure readings as well as biologic samples for laboratory measurements. Participants were then randomized to receive either atenolol 50 mg/day or HCTZ 12.5 mg/day. After 3 weeks on the initial dose, participants with an average home or office systolic blood pressure higher than 120 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure higher than 70 mm Hg received a dose titration. After at least 6 additional weeks at the target dose, comprehensive blood pressure measures (home, office, and ambulatory) and biologic samples were again obtained (first response assessment or monotherapy assessment). Participants with blood pressure higher than 120/70 mm Hg at monotherapy assessment then had the alternative study medication added, with the same dose titration and response assessment schedule (second response assessment or combination therapy assessment).

Laboratory Measurements

At all three study visits (baseline, monotherapy, and combination therapy), fasting blood samples were collected for glucose, insulin, potassium, uric acid, creatinine, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglycerides. Fasting was defined as having consumed no food or beverages other than water for at least 8 hours prior to the visit. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation.17 If a change in glucose between study visits was outside the sample mean by more than 3 SD, the data were considered to be outliers (potentially nonfasting) and excluded from analysis.

Biochemical Assays

Serum glucose, HDL cholesterol, uric acid, potassium, and triglycerides were quantified on a Hitachi 911 Chemistry Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) at the central laboratory at the Mayo Clinic. Serum glucose, HDL cholesterol, uric acid, potassium, and triglycerides concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically by automated enzymatic assays, and potassium concentrations were determined by an ion selective electrode. LDL cholesterol was calculated using the Friedewald formula.18 Plasma insulin levels were measured using the Access Ultrasensitive Insulin immunoassay system (Beckman Instruments). All of the samples were tested in duplicate; data used in the analyses are the means of the duplicate samples for each participant.

Anthropometric Measurements

Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg; height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm. Waist circumference was measured by trained study personnel by placing a tape measure snuggly around the abdomen at the level of the umbilicus, slightly above the uppermost lateral border of the right iliac crest. Waist circumference was measured while the participant was standing, with hands at the side and normal to minimal respirations.

Statistical Methods

The continuous variables are summarized as mean and SD or median and interquartile range (IQR) as appropriate, and categorical variables are summarized as number and percentage. Continuous variables between the treatment strategies were compared with two sample t tests if the data were normally distributed or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test if not. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test.

Outcome

Fasting glucose change after treatment was analyzed as a continuous variable and was calculated as posttreatment–treatment value in milligrams per deciliter. Development of IFG (new occurrence of fasting glucose of 100 mg/dl or higher after treatment with atenolol or HCTZ) was evaluated as a binary variable. Participants with a glucose of 100 mg/dl or higher at baseline were excluded from this analysis.

Cohort Selection

To develop and then validate a prediction model, PEAR participants were randomly divided into derivation and validation cohorts using the survey-select procedure in SAS software.

Model Building and Validation

The glucose change was analyzed with linear regression, and new onset of IFG was analyzed with logistic regression. In the derivation cohort, variables with a p value <0.2 in univariate analysis were considered in subsequent stepwise multiple regression model building. Variables tested in the univariate model included age, sex, randomization assignment, race (black or non-black), alcohol consumption (beverages per week), smoking status, waist circumference, estimated GFR, days treated with study medication, and baseline values for systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate as measured by home blood pressure monitor, as well as baseline glucose, insulin, uric acid, potassium, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL, and LDL.

The race variable, black or nonblack, was based on self-identified race and confirmed by principal component clustering with African ancestry or non-African ancestry based on genome-wide genotype data from Illumina Human-Omni1M chip. Waist circumference was selected as the body size parameter used in the models based on the detrimental physiologic effects of abdominal obesity, such as secretion of free fatty acids, hormones, and inflammatory markers,19–24 as well as the associated elevated cardiovascular risk that is independent of other body size parameters.25–31 After univariate analysis, a stepwise linear or logistic regression selection procedure was used: variables with a p value <0.05 were considered significant predictors and retained in the final models.

The correlation between the predicted (based on the regression equation from the derivation cohort) and the observed drug-associated change in glucose was evaluated in the validation cohort for the glucose response analysis. To evaluate the logistic regression models in the validation cohort for the IFG analysis, area under the receiver operating curve (ROC) and Hosmer-Leme-show test of goodness of fit were performed. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 768 participants were considered in the initial analysis. From these, 33 participants were excluded due to missing data in either glucose value or waist circumference or outlier in glucose response (Figure S1). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics as well as clinical and laboratory parameters of the remaining 735 participants included in this analysis. PEAR participants were on average 49 years old, with slightly fewer men enrolled (47%) than women, and ∼39% of the participants were of African ancestry. The median baseline glucose in the derivation and validation cohorts was 89.5 (IQR 84.5–98.0) mg/dl and 89.5 (IQR 83.5–96.0) mg/dl, respectively. No baseline demographics, clinical, or laboratory parameters were significantly different between the derivation and validation cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Demographics and Clinical and Laboratory Parameters.

| PEAR n=735 | Derivation cohort n=367 | Validation cohort n=368 | p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 48.93 ± 9.19 | 49.02 ± 9.38 | 48.85 ± 9.01 | 0.81 |

| Male, % | 47.08 | 47.14 | 47.01 | 0.97 |

| African American, % | 39.32 | 37.33 | 41.30 | 0.27 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 97.75 ±13.10 | 97.61±12.70 | 97.89± 13.51 | 0.77 |

| Drinks/wk | 1.93 ± 4.03 | 2.05 ± 4.29 | 1.80 ± 3.75 | 0.41 |

| Current smoker, % | 14.42 | 13.90 | 14.95 | 0.69 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2) | 98.07 ± 21.44 | 98.69 ± 23.38 | 97.46 ± 19.31 | 0.44 |

| Home SBP, mm Hg | 145.83 ± 10.34 | 145.80 ± 9.72 | 145.85 ± 10.94 | 0.95 |

| Home DBP, mm Hg | 93.78 ± 5.95 | 94.04 ± 5.86 | 93.52 ± 6.04 | 0.23 |

| Pulse, bpm | 77.45 ± 9.40 | 77.48 ± 8.99 | 77.41 ± 9.80 | 0.92 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 91.12 ± 11.38 | 91.49 ± 11.61 | 90.74 ± 11.16 | 0.37 |

| Insulin, lIU/ml | 9.16 ± 8.03 | 9.01 ± 8.26 | 9.31 ± 7.80 | 0.61 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 5.59 ± 1.44 | 5.59 ± 1.45 | 5.59 ± 1.43 | 0.99 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 4.26 ± 0.43 | 4.25 ± 0.42 | 4.27 ± 0.44 | 0.50 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 194.28 ± 35.64 | 193.37 ± 35.61 | 195.19 ± 35.69 | 0.49 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 126.24 ± 91.29 | 131.90 ± 102.60 | 120.58 ± 78.12 | 0.093 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 49.37 ± 14.15 | 48.63 ± 13.19 | 50.10 ± 15.04 | 0.16 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 120.28 ± 30.63 | 119.44 ± 30.89 | 121.10 ± 30.39 | 0.47 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean + SD; categorical variables are presented as percentages.

bpm = beats per minute; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; PEAR = Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

The p value compares between derivation and validation cohorts; continuous variables were compared with t test, and categorical variables were compared with χ2 test.

Glucose Change after Atenolol or HCTZ Treatment

Overall, 86% of the patients assigned to ateno-lol monotherapy and 98% of the patients assigned to HCTZ monotherapy were titrated to the higher doses of either atenolol (100 mg/day) or HCTZ (25 mg/day). Following 9 weeks of atenolol monotherapy, median glucose was increased from 89–92 mg/dl. When atenolol was added to existing HCTZ treatment, median glucose increased from 91.5–94 mg/dl (p=0.60, atenolol monotherapy vs atenolol add-on). Following 9 weeks of HCTZ monotherapy, median glucose increased from 90.5–91.5 mg/dl; after HCTZ was added to existing atenolol treatment, the median glucose increased from 92– 94 mg/dl (p=0.55, HCTZ monotherapy vs HCTZ add-on). Because the change in glucose after monotherapy and add-on therapy was not statistically different for either HCTZ or atenolol, monotherapy and add-on response data were combined for all the following analyses adjusting for the treatment strategy and pretreatment glucose levels. After treatment with either study medication, median glucose change was similar +2.0 (IQR −3.5 to +7.0) mg/dl for atenolol and +2.0 (IQR −3.5 to +7.5) mg/dl for HCTZ.

The glucose change from the combination therapy of atenolol and HCTZ was also evaluated. For participants treated with atenolol monotherapy followed by HCTZ add-on therapy, the median glucose increased from 89–94 mg/dl. For participants treated with HCTZ monotherapy followed by atenolol add-on therapy, the median glucose was increased from 90.5–94 mg/dl.

All analyses were initially conducted in the 367 participants in the derivation cohort. The models were then assessed in the 368 participants in the validation cohort. For atenolol-associated glucose change, the variables meeting the criteria in univariate analysis to be carried forward (p<0.2) included baseline glucose (p<0.0001), baseline insulin (p=0.0009), and baseline uric acid (p=0.11) (Table 2). Baseline glucose (p<0.0001, β = −0.30 mg/dl) was the only characteristic that remained significant in multiple linear regression analysis. Each unit (in milligrams per deciliter) decrease in baseline glucose level was associated with a 0.30 mg/dl higher glucose change after atenolol therapy. This model explained 13.06% of the variability in change in glucose in the derivation cohort.

Table 2. Univariate Analysis for Atenolol- or Hydrochlorothiazide-Induced Change in Glucose in the Derivation Cohorts.

| Predictor measured | Atenolol (n=355) | Hydrochlorothiazide (n=352) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| β ± SE | p value | β ± SE | p value | |

| Age, yrs | 0.01 ± 0.06 | 0.88 | 0.05 ± 0.05 | 0.36 |

| Sex, male | 0.45 ± 1.08 | 0.68 | −2.68 ± 0.99 | 0.0072 |

| Race, African American | −0.93 ± 1.11 | 0.40 | 1.16 ± 1.03 | 0.26 |

| Assignment, atenolol | 0.88 ± 1.08 | 0.41 | −0.01 ± 1.00 | 0.99 |

| Duration of therapy, days | 0.01 ± 0.03 | 0.73 | −0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.17 |

| Waist circumference, cm | −0.01 ±0.04 | 0.82 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.43 |

| Drinks/week | 0.01 ± 0.12 | 0.95 | −0.11 ± 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Current smoker, % | 1.30 ± 1.58 | 0.41 | −0.72 ± 1.45 | 0.62 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.73 |

| Home SBP, mm Hg | 0.04 ± 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.01 ± 0.04 | 0.81 |

| Home DBP, mm Hg | −0.01 ±0.08 | 0.99 | 0.03 ± 0.06 | 0.56 |

| Pulse, bpm | 0.01 ± 0.06 | 0.94 | −0.04 ±0.05 | 0.50 |

| Pretreatment glucose, mg/dl | −0.31 ± 0.04 | < 0.0001 | −0.28 ±0.04 | < 0.0001 |

| Insulin, lIU/ml | −0.17 ± 0.05 | 0.0009 | −0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.013 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | −0.51 ±0.32 | 0.11 | −0.16 ± 0.35 | 0.65 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 0.44 ± 1.15 | 0.70 | −0.11 ± 1.18 | 0.93 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.59 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.50 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.47 | −0.01 ±0.01 | 0.65 |

| HDL, mg/dl | −0.03 ± 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.05 ± 0.04 | 0.19 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.93 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 0.29 |

DBP = diastolic blood pressure; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low=density lipoprotein; SBP = systolic blood pressure; SE = standard error.

For HCTZ-associated glucose change, variables that passed univariate analysis screening included baseline glucose (p<0.0001), baseline insulin (p=0.013), baseline HDL (p=0.19), duration of HCTZ therapy (p=0.17), and sex (p=0.0072) (Table 2). After stepwise multiple linear regression, baseline glucose (p<0.0001) was the only variable to remain significant for HCTZ-associated glucose change. Each mg/dl unit decrease in baseline glucose level was associated with a 0.28 mg/dl increase in glucose change after HCTZ therapy. This regression model explained 12.11% of the variability in change in glucose in the derivation cohort.

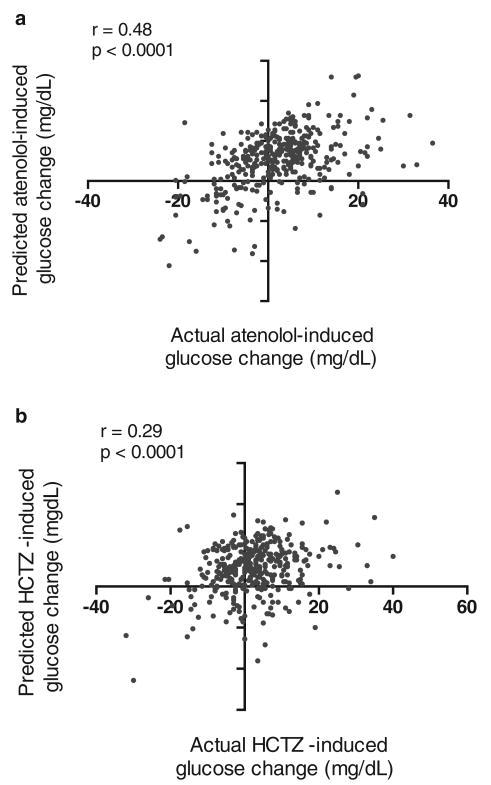

The correlation between the model-predicted versus actual glucose change in the validation cohort was significant for atenolol and HCTZ (r = 0.48 for atenolol model; r = 0.29 for HCTZ model; p<0.0001 for both models; Table 3; Figure 1). For both atenolol and HCTZ treatment-associated glucose change, the average predicted change in glucose was within 0.3 mg/dl of the average observed change in glucose (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation between Model-Predicted Medication-Associated Glucose Change and Actual Medication-Associated Glucose Change in Validation Cohort.

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATEN | ||||

| Predicted Δ glucose, mg/dl | 2.20 | 3.62 | −11.22 | 12.86 |

| Actual Δ glucose, mg/dl | 2.14 | 9.51 | −24.00 | 36.50 |

| R | 0.48 | |||

| p value | < 0.0001 | |||

| Y = 30.23 − 0.30 × baseline glucose | ||||

| HCTZ | ||||

| Predicted Δ glucose, mg/dl | 2.17 | 2.96 | −11.36 | 11.49 |

| Actual Δ glucose, mg/dl | 2.42 | 9.54 | −32.00 | 40.00 |

| R | 0.29 | |||

| p value | < 0.0001 | |||

| Y = 27.65 − 0.28 × baseline glucose | ||||

ATEN = atenolol; HCTZ = hydrochlorothiazide.

Figure 1.

Correlation between model-predicted glucose and actual change in validation after treatment (a) after atenolol therapy; (b) after hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) therapy.

Impaired Fasting Glucose after Atenolol or HCTZ Treatment

In the derivation cohort for atenolol treatment, 279 participants had baseline glucose of less than 100 mg/dl, and 43 (15.4%) developed new-onset IFG (Figure S1). The univariate logistic regression analysis for new-onset IFG after atenolol treatment resulted in age (p=0.0071), black race (p=0.02), male sex (p=0.20), waist circumference (0.10), baseline glucose (p=0.0002), insulin (p=0.073), potassium (p=0.049), and HDL cholesterol (p=0.19) that were carried forward in the stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis (p<0.20; Table 4). After multiple logistic analysis, age (per year) (odds ratio [OR] 1.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.09, p=0.019) and baseline glucose (OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.04–1.17, p=0.0005) were the only significant predictors for IFG after atenolol treatment. Every year increase in age was associated with a 5% increased risk for IFG, and every unit increase in baseline glucose (in mg/dl) was associated with 11% higher odds of developing IFG after atenolol treatment. This logistic regression model was assessed in the validation cohort of 280 participants with baseline glucose of less than 100 mg/dl, the area under the ROC curve was 0.77, and Hosmer-Lemeshow test of goodness-of-fit p value was 0.53, indicating a very good fit of the model.

Table 4. Univariate Analysis for Medication-Associated Development of New-Onset Impaired Fasting Glucose (Glucose ≥100 mg/dl), Derivation Cohort.

| Predictor measured | Atenolol (n=279) | Hydrochlorothiazide (n=269) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age, yrs | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | 0.0071 | 1.04 | 1.00–1.08 | 0.052 |

| Sex, male | 1.54 | 0.80–2.95 | 0.197 | 1.15 | 0.59–2.23 | 0.69 |

| Race, African American | 0.4 | 0.18–0.87 | 0.021 | 1 | 0.51–1.98 | 0.99 |

| Assignment, atenolol | 0.9 | 0.47–1.72 | 0.75 | 1.27 | 0.66–2.48 | 0.48 |

| Length of therapy, days | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.45 | 1 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.86 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 1.02 | 1.00–1.05 | 0.10 | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | 0.0007 |

| Drinks/week | 1.03 | 0.96–1.09 | 0.44 | 1.01 | 0.93–1.08 | 0.95 |

| Current smoker, % | 1.34 | 0.54–3.27 | 0.53 | 2.06 | 0.85–4.97 | 0.11 |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2) | 1 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.58 | 0.99 | 0.98–1.01 | 0.33 |

| Home SBP, mm Hg | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.27 | 1 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.81 |

| Home DBP, mm Hg | 0.97 | 0.93–1.02 | 0.27 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.03 | 0.49 |

| Pulse, bpm | 1.01 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.65 |

| Pretreatment glucose, mg/dl | 1.11 | 1.05–1.18 | 0.0002 | 1.22 | 1.13–1.32 | < 0.0001 |

| Insulin, lIU/ml | 1.05 | 1.00–1.11 | 0.07 | 1.09 | 1.03–1.15 | 0.0017 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 0.95 | 0.79–1.16 | 0.63 | 1.11 | 0.89–1.40 | 0.39 |

| Potassium, mEq/L | 2.04 | 1.01–4.14 | 0.05 | 3.56 | 1.61–7.88 | 0.0017 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.39 | 1 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.43 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dl | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.24 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.39 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 | 0.19 | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | 0.16 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.42 | 1 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.63 |

bpm = beats per minute; CI = confidence interval; DBP = diastolic blood pressure; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; OR = odds ratio; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

In the derivation cohort of the 269 participants treated with HCTZ with baseline glucose less than 100 mg/dl, 41 (15.2%) developed new-onset IFG (Figure S1). As the result of the univariate logistic regression analysis for new-onset IFG after HCTZ treatment, age (p=0.052), waist circumference (p=0.0007), current smoking (p=0.11), baseline glucose (p<0.0001), insulin (p=0.0017), potassium (p=0.0017), and HDL cholesterol (p=0.16) were pulled into multiple logistic regression (p<0.20; Table 4). When evaluated through multiple logistic regression, baseline glucose (OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.09–1.22, p<0.0001) and waist circumference (per centimeter) (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.07, p=0.018) remained as significant predictors. Every unit increase in baseline glucose (in mg/dl) was associated with 15% higher odds of developing IFG; and every unit increase in waist circumference (in cm) was associated with 3% higher risk for developing IFG after HCTZ treatment. This model was assessed in the validation cohort of 293 participants treated with HCTZ, the area under the ROC curve was 0.71, and Hosmer-Lemeshow test of goodness-of-fit p value was 0.08.

Discussion

Our analysis showed that baseline glucose is an important predictor of medication-associated glucose change after treatment with either atenolol or HCTZ. Baseline glucose was also predictive of development of IFG after treatment with either medication. In addition, age was associated with IFG after atenolol treatment, and waist circumference was associated with IFG after treatment with HCTZ. This provides the basis for covariates that should be adjusted to identify genetic predictors for glucose change and IFG after treatment with atenolol or HCTZ.

Studies have shown that even for individuals with normal fasting glucose, the risk for diabetes increases as fasting glucose levels increase.32, 33 We have found that ∼9 weeks of exposure to atenolol or HCTZ was associated with a 2–3 mg/dl increase in the fasting glucose value. We also found that the glucose increase following the combination therapy of atenolol and HCTZ (in either order) was close to being additive (∼4 mg/dl). Even though this magnitude appears relatively small, long-term continuous exposure to these drugs could have clinically significant consequences. In a study of more than 45,000 individuals with a mean follow-up of 81 months, each mg/dl increase in fasting glucose was associated with a 6% higher risk for diabetes (hazard ratio 1.06, 95% CI 1.05–1.07).32 In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, IFG was associated with a 13 times higher risk of type 2 diabetes compared with normal fasting glucose.34 Due to the long-term nature of antihy-pertensive treatment, it is important to identify predictors of glucose change and the risk of IFG. Our data suggest that hypertensive patients at high risk of diabetes should avoid β-blockers and thiazide diuretics, especially in combination.

We found a lower baseline glucose value associated with a greater increase in glucose after drug therapy. A study similar to the present study also found lower baseline glucose to be significantly predictive of greater glucose increase in response to HCTZ. Another study sought to evaluate clinical and genetic predictors of adverse metabolic effects after HCTZ treatment. The researchers found a mean increase in glucose of 3.5 ± 9.5 mg/dl, with ∼11% of the variation explained by clinical predictors that included African ancestry, lower baseline glucose, and lower urinary sodium excretion. In our study, ∼12–13% of the variability in glucose change following antihypertensive treatment was explained by baseline glucose.

Further, when we conducted the analysis for new onset of IFG, we found that higher baseline glucose predicted higher risk of new-onset IFG after either atenolol (11% higher risk for each unit increase) or HCTZ treatment (19% higher risk for each unit increase). This is consistent with a recently published longitudinal study of healthy individuals reporting higher baseline glucose level associated with higher risk of incident IFG, with each unit increase in baseline glucose associated with a 16% higher risk.35

Data from PEAR suggest that lower baseline glucose predicted a greater change in glucose, whereas higher baseline glucose predicted an increased risk of new-onset IFG. These discrepancies emphasize two fundamental differences between measuring change in glucose as a continuous variable or as a dichotomous value. As a continuous variable, the amount of glucose increase may be more strongly associated with lower values. As a dichotomous value, movement across the dichotomous cut point is greatest the closer the value is to a threshold. Thus predictors of new-onset IFG represent more distinct research questions than just an evaluation of the magnitude of drug-associated glucose change. These findings suggest that baseline glucose is important in predicting adverse glycemic changes from antihypertensive medications, whether the change is an elevation in glucose or overt IFG development.

Our study has some relevant limitations that should be considered. An important aspect of our analysis included combining atenolol or HCTZ monotherapy with add-on therapy (+atenolol add-on or +HCTZ add-on, respectively) associated responses, irrespective of the order the medications were given. Although it is possible that the order of medications administered may have an impact on the degree of resulting glucose elevation, this did not appear to be the case. The change in glucose was very similar between monotherapy and add-on therapy; to our knowledge there are no data suggesting otherwise. Moreover, in the clinical setting, these drugs are administered either alone or as add-on therapy. Additionally, PEAR measured fasting glucose as opposed to oral glucose tolerance based on an oral glucose tolerance test. Although serial oral glucose tolerance testing is an excellent way to assess changes in glucose tolerance and insulin resistance,36 fasting glucose was sufficiently sensitive to detect glycemic changes associated with antihypertensive medication during the study period. Finally, although our sample size may have been smaller than previous studies evaluating glucose change after antihypertensive medications,37 we believe use of derivation and validation cohorts strengthen our findings.

Conclusion

We found baseline glucose to be the strongest and most consistent predictor of atenolol-or HCTZ-associated glucose change and new-onset IFG. Further study is warranted to establish whether factors such as genetic polymorphisms may also predict glucose change following treatment with these two classes of antihypertensives.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Flow diagram of PEAR participants analyzed in the derivation cohort and validation cohort.

Acknowledgments

PEAR was supported by the National Institute of Health Pharmacogenomic Research Network grant (U01 GM074492) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences under the award number UL1 TR000064 (University of Florida), UL1 TR000454 (Emory University), and UL1 TR000135 (Mayo Clinic). PEAR was also supported by funds from the Mayo Foundation. MJM was supported by T32 HL083810-01. ALB was supported by K23 HL091120. RCD was supported by K23HL086558. We also acknowledge and thank the valuable contributions of the study participants, support staff, and study physicians: Drs. George Baramidze, Carmen Bray, Kendall Campbell, Frederic Rabari-Oskoui, and Dan Rubin.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: The following supporting information is available in the online version of this paper:

References

- 1.Elliott WJ, Meyer PM. Incident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:201–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahl€of B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the Losartan Intervention For End-point reduction in hypertension study (LIFE): a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet. 2002;359:995–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper-Dehoff R, Cohen JD, Bakris GL, et al. Predictors of development of diabetes mellitus in patients with coronary artery disease taking antihypertensive medications (findings from the INternational VErapamil SR-Trandolapril STudy [INVEST]) Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:890–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangalore S, Parkar S, Grossman E, Messerli FH. A meta-analysis of 94,492 patients with hypertension treated with beta blockers to determine the risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1254–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahl€of B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, et al. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendrof-lumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895–906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67185-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stump CS, Hamilton MT, Sowers JR. Effect of antihyperten-sive agents on the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:796–806. doi: 10.4065/81.6.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter BL, Einhorn PT, Brands M, et al. Thiazide-induced dysglycemia: call for research from a working group from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Hypertension. 2008;52:30–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper-DeHoff RM. Thiazide-induced dysglycemia: it’s time to take notice. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:1291–4. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.10.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chrysant SG, Chrysant GS, Dimas B. Current and future status of beta-blockers in the treatment of hypertension. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:249–52. doi: 10.1002/clc.20249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verdecchia P, Reboldi G, Angeli F, et al. Adverse prognostic significance of new diabetes in treated hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004;43:963–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000125726.92964.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Wen S, Beitelshees AL, et al. Impact of abdominal obesity on incidence of adverse metabolic effects associated with antihypertensive medications. Hypertension. 2010;55:61–8. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maitland-van dZA, Turner ST, Schwartz GL, Chapman AB, Klungel OH, Boerwinkle E. Demographic, environmental, and genetic predictors of metabolic side effects of hydrochlorothia-zide treatment in hypertensive subjects. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:1077–83. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almgren T, Wilhelmsen L, Samuelsson O, Himmelmann A, Rosengren A, Andersson OK. Diabetes in treated hypertension is common and carries a high cardiovascular risk: results from a 28-year follow-up. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1311–7. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328122dd58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aksnes TA, Kjeldsen SE, Rostrup M, Omvik P, Hua TA, Julius S. Impact of new-onset diabetes mellitus on cardiac outcomes in the Valsartan Antihypertensive Long-term Use Evaluation (VALUE) trial population. Hypertension. 2007;50:467–73. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.085654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunder K, Lind L, Zethelius B, Berglund L, Lithell H. Increase in blood glucose concentration during antihyperten-sive treatment as a predictor of myocardial infarction: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326:681. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7391.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson JA, Boerwinkle E, Zineh I, et al. Pharmacogenomics of antihypertensive drugs: rationale and design of the Phar-macogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses (PEAR) study. Am Heart J. 2009;157:442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sepe A, Tchkonia T, Thomou T, Zamboni M, Kirkland JL. Aging and regional differences in fat cell progenitors—a mini-review. Gerontology. 2011;57:66–75. doi: 10.1159/000279755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poledne R, Lorenzova A, Stavek P, et al. Proinflammatory status, genetics and atherosclerosis. Physiol Res. 2009;58(Suppl 2):S111–8. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boden G, Shulman GI. Free fatty acids in obesity and type 2 diabetes: defining their role in the development of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction. Eur J Clin Invest. 2002;32(Suppl 3):14–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.32.s3.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis GF, Carpentier A, Adeli K, Giacca A. Disordered fat storage and mobilization in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:201–29. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.2.0461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjorntorp P. Metabolic implications of body fat distribution. Diabetes Care. 1991;14:1132–43. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.12.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2005;96:939–49. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–97. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider HJ, Friedrich N, Klotsche J, et al. The predictive value of different measures of obesity for incident cardiovascular events and mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1777–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghandehari H, Le V, Kamal-Bahl S, Bassin SL, Wong ND. Abdominal obesity and the spectrum of global cardiometabolic risks in US adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009;33:239–48. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet. 2005;366:1640–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dagenais GR, Yi Q, Mann JF, Bosch J, Pogue J, Yusuf S. Prognostic impact of body weight and abdominal obesity in women and men with cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;149:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leitzmann MF, Moore SC, Koster A, et al. Waist circumference as compared with body-mass index in predicting mortality from specific causes. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e18582. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Testa G, Cacciatore F, Galizia G, et al. Waist circumference but not body mass index predicts long-term mortality in elderly subjects with chronic heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1433–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols GA, Hillier TA, Brown JB. Normal fasting plasma glucose and risk of type 2 diabetes diagnosis. Am J Med. 2008;121:519–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tirosh A, Shai I, Tekes-Manova D, et al. Normal fasting plasma glucose levels and type 2 diabetes in young men. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1454–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeboah J, Bertoni AG, Herrington DM, Post WS, Burke GL. Impaired fasting glucose and the risk of incident diabetes mell-itus and cardiovascular events in an adult population: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cicero AF, Derosa G, Rosticci M, et al. Long-term predictors of impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes in subjects with family history of type 2 diabetes: a 12-years follow-up of the Brisighella Heart Study historical cohort. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;104:183–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the eu-glycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1462–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barzilay JI, Davis BR, Cutler JA, et al. Fasting glucose levels and incident diabetes mellitus in older nondiabetic adults randomized to receive 3 different classes of antihypertensive treatment: a report from the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2191–201. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Flow diagram of PEAR participants analyzed in the derivation cohort and validation cohort.