Abstract

Children with deafness who are also on the autistic spectrum are a group with complex support needs. Carers worry about their ability to communicate with them, and are often uncertain about what constitutes ‘good’ communication in this context. This paper analyses the use of a therapeutic intervention, Video Interaction Guidance (VIG), which originates in developmental psychology and focuses on the relational foundations of communication. We draw on a single case using an ethnomethodological/conversation analytic framework, and in particular Goodwin's (1994) work on ‘professional vision’, to show how the ability to see ‘success’ is a socially situated activity. Since what counts as success in this setting is often far removed from everyday ideas of good communication, how guiders facilitate particular ‘ways of seeing’ are critical for both the support of carers and the impact of the intervention. We argue that this work has implications in three areas: for the practice of VIG itself; for the role of qualitative, interactional research addressing the way in which interaction-based interventions are protocolised, enacted and assessed; and for the way in which expertise is conceptualised in professional/client interactions in health and social care.

Keywords: United Kingdom, Autistic spectrum disorder, Hearing impairment, Video interaction guidance, Ethnomethodology, Conversation analysis, Qualitative research, ‘Professional vision’

Highlights

-

•

VIG depends on mutual identification and perception of ‘successful’ communication.

-

•

To achieve this, guiders facilitate particular ‘ways of seeing’.

-

•

Explicating the process of talk-based interventions is critical for their integrity.

-

•

Interventions casting parents as ‘co-workers’ affect how we view and enact expertise.

Introduction

Children with deafness who are also on the autistic spectrum are a group with complex support needs. Carers worry about their ability to communicate with them, and are often uncertain about what constitutes ‘good’ communication in this context. This paper analyses the use of a therapeutic intervention, Video Interaction Guidance (VIG), which originates in developmental psychology and focuses on the relational foundations of communication (Murray and Trevarthen, 1985, Trevarthen, 1974). VIG is based on observation of real life communication, between carer and child, captured on video. Excerpts from this video are then selected by the guider and played back to the carer, to demonstrate what the guider has identified as successful communicative events and to aim to co-construct an understanding of the success of the moment. In this way it is hoped participants will perceive existing positive contingencies and be able to build upon them in future communication. Early evaluation of the intervention indicates a significant impact (Fukkink, 2008), but its success ultimately relies upon the process of co-construction, so that aspects of communication can be mutually perceived as successful. In this paper we draw on a single case using an ethnomethodological/conversation analytic framework, and in particular Goodwin's (1994) work on ‘professional vision’, to show how the ability to see ‘success’ is a socially situated activity. Since what counts as success in this setting is often far removed from everyday ideas of good communication, how guiders facilitate particular ‘ways of seeing’ are critical for both the support of carers and the impact of the intervention. Current UK Medical Research Council guidance on the use of interventions (MRC, 2008) states that where a ‘complex’ intervention such as VIG is used, researchers must consistently provide as close to the same interaction as possible in order to preserve its integrity. For this to be possible, it has been argued that integrity must be defined functionally, with an emphasis on process above other aspects (Hawe, Shiell, & Riley, 2004). Identifying and examining the interactional processes through which an intervention like VIG occurs is therefore of wider significance. Put another way, in order to critically explore the utility of VIG, it is necessary to first examine how it operates in practice. The analysis presented here begins such an examination.

Background

Goodwin's work on ‘professional vision’ sets out to show the discursive practices “used by members of a profession to shape events in the phenomenal environment they focus their attention upon, the domain of their professional scrutiny, into the objects of knowledge that become the insignia of their profession” (1994: p. 606). Through shaping in particular ways, objects of knowledge are created that are the special domain of a particular profession.

Through his analysis, Goodwin shows how participants build a particular ‘professional vision’, a socially organised way of seeing and understanding events that pertain to the specific interests of a particular professional group. The example that perhaps most clearly illustrates different ‘ways of seeing’ relating to specific interests is one that Goodwin himself uses: the trial of 4 white policemen who were initially acquitted of beating black motorist Rodney King in LA in 1992, despite the fact that the beating was filmed by a passer-by. Goodwin's analysis of footage from the trial demonstrates how lawyers for both sides were able to structure the happenings visible on the video in ways that suited their own agendas. What appeared at face value as police brutality towards an innocent motorist was, through a set of discursive practices, transformed by the defence into a reasonable police response towards a potentially dangerous man. Rather than treating the tape as a record that spoke for itself, the defence lawyers presented it as something that could be understood only by embedding the events visible on it within the work life of a profession, and by framing the ways in which these events should be so perceived.

In considering how this framing was actually achieved across this and other settings, Goodwin identified 3 specific practices. Firstly, coding schemes were used to transform the materials that were being attended to in a specific setting into objects of knowledge. Secondly, the use of highlighting; particular phenomena in a complex perceptual field were made particularly salient by marking them out in some way. Thirdly, framing was assisted by the production and articulation of graphic representations of a field, such as maps, charts, transcripts etc.

As Goodwin argues, then, the conduct of this trial provides an example of how being able to see a meaningful event is not a transparent, psychological process, but is instead a socially situated activity. Vision is lodged within communities of practice,1 and individuals from different communities will see different things in the same object or event, just as an archaeologist and a farmer will see different things in the same patch of dirt. As we will see from the data that follow, parents/carers and professionals involved in VIG may also see very different things in a communicative exchange with a child, and so how things become agreed on as a ‘moment of success’ is equally socially situated. In addition, as we have alluded to earlier, not only what is taken to count as a ‘moment of success’ but how that moment is agreed upon is also of fundamental importance for the wider utility of VIG, and its integrity as an intervention.

Goodwin's concept of professional vision has previously been used to examine interaction in a variety of healthcare settings, most commonly involving situations where an experienced practitioner is in some kind of training or teaching role and needs to make a judgement about the competency of a less experienced practitioner to ‘see’ significant aspects of a case. As Koschmann and LeBaron (2003) note, drawing on their work in an operating theatre setting, how participants to a joint activity come to develop a shared or mutual understanding of what they are perceiving has long been of interest to researchers across the human and social sciences. In practical terms, how we detect when discrepancies in what we see have arisen, and how we try to reconcile these, is critical for safe and effective practice in a wide range of clinical settings. Hindmarsh, Reynolds, and Dunne's (2011) work on dentistry highlights how Sacks' (1992: p. 252) distinction between ‘claiming’ and ‘exhibiting’ understanding is of paramount importance in the supervisor/supervised relationship in healthcare. Supervisors draw on a range of resources when making judgements on this distinction, both verbal and non-verbal.

However, as the terminology used in the VIG intervention suggests, the ‘guider’ in this setting is not in a straightforward teaching or tutoring relationship with the parent/carer or professional who is involved with the intervention. This creates a potentially delicate scenario. As Pomerantz (2003) and Pomerantz, Fehr, and Ende (1997) observe, the activity of teaching defines at the outset the one being taught as not fully competent. However, the competency that is at issue here is not one that relates to a technical or professional healthcare skill (such as taking a patient history or conducting a physical examination), but one that might broadly be defined as ‘interacting more effectively with your child’. Explicit teaching activity in this setting would risk being seen as inappropriate both in terms of its threat to parental competency, but also to the integrity of the intervention. Unlike the settings which Hindmarsh et al. (2011) and Pomerantz et al. (1997) describe, guiders cannot and should not explicitly teach. However, in common with these other healthcare settings, in order for the intervention to have any impact, guiders must be sure that parents or carers can ‘see for themselves’.

Applying the concept of ‘professional vision’ to VIG

Video Interaction Guidance is becoming embedded in the UK public sector. In some Local Authority areas there is a locally funded strategic initiative to implement VIG, so that it becomes part of routine practice. In other cases individual practitioners enter training as part of their continuing professional development. There are approximately 500 practitioners of VIG in the UK including educational psychologists, speech and language therapists, teachers, social workers, family therapists and academics. As a result of this diversity, children and families are identified for participation in VIG in different ways, from routine service delivery through to specific trials and projects. The data presented in this paper come from a specific study aimed at assessing the utility of VIG with a particular client group.

VIG is designed as a family centred intervention. It begins with the parent/carer (or sometimes the professional) working with the child being asked to identify areas for improvement/issues of concern. From these areas of concern, goals for change are formulated. Video is taken by the guider at the home or school setting, following the guidelines laid down by Kennedy, Landor, and Todd (2011). Typically, no more than 15–20 min of film footage would be taken, and the place, activity and focus for recording are jointly agreed at the time the goals for change are established. The video is then watched by the ‘guider’ in order to identify relevant ‘moments of success’ related to these goals. For example, if a parental goal was for more co-operation from a child, the guide would seek to find clips where co-operation was evident, however briefly it might initially occur.

VIG training for guiders consists of a two day introductory course and three phases of training. These consist of 25 h of individual supervision spread over a minimum of 18 months. There are three accreditation days during this period which must be passed. To assist in the identification of ‘moments of success’ from the video recordings, VIG utilises a framework based on 4 key elements of successful relational interaction, referred to as the ‘contact principles’ (see Appendix 1). These principles are initiative and reception; interaction; giving guidance through discussion; giving guidance through conflict management (James, Falck, Hall, Phillipson, & McCrossan, 2013). Specific elements of these principles are outlined, so that for example the need to give and receive initiatives relies on being attentive and attuned, which may be displayed through body posture, eye contact etc. The identified video clips are then played back to the parent/carer/professional to guide them in seeing this success. Once success is mutually recognised and identified, the aim is to unpack what it is about that moment that contributes to its success, and how this might then be applied in future interactions. In effect, as James (2011) has argued, it requires parents/carers and professionals to become co-workers in the process of seeing success. The more general argument about shared understanding that Clark (1996) makes is clearly relevant to this setting. For the success of the intervention, parents/carers and professionals need to be able to see not only what is visible (in the sense of having access to the same materials as the intervention guider), but also to be able to see it in the same way as the guider.

Goodwin outlines how, through the application of professional vision, an event being seen becomes an object of knowledge – e.g., in the Rodney King trial, a proportional response by police. This object of knowledge emerges through “the interplay between a domain of scrutiny (…the images made available by the King videotape etc) and a set of discursive practices (…highlighting, applying particular coding schemes for the interpretation of relevant events etc) being deployed within a specific activity (arguing a legal case)” (1994: p. 606). In the context of VIG, the object of knowledge is successful communication. The domain of scrutiny is the video made by the guider of naturally occurring events in home and school settings. Taking a single case as an example, this paper aims to investigate the practices used within VIG to identify and reinforce successful communication. It is perhaps an obvious point but one that is worth underlining – that to analyse how practice is organised in this way requires video data: at the heart of the VIG intervention is that participants need to be able to see success for themselves, and also to have a shared understanding of this success.

Methods

The case presented in this paper is taken from a piece of clinical work that was completed by the second named author of this manuscript while employed as lead scientist at the University of Nottingham, where she was running a single-subject exploratory clinical trial in VIG funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research and approved by Derbyshire NHS Research Ethics Committee. The trial ran from November 2011 to April 2012. The case is taken from an overall corpus of 19 recorded as part of the pilot work and clinical trial, of which 5 cases were examined in the detail presented here. An information sheet was given to participants before consent was sought, and they were also invited to watch a DVD with captioning available in any language and British Sign Language captioning. Participants were told that the VIG sessions would be recorded in order to find out more about how and why the intervention worked, and that a key focus of analysis would be what the guide was saying and doing.

The case has been selected as a typical illustration of a VIG session in this setting. ‘Typical’ in this sense refers to the number of times the recording is viewed (in our corpus, after the initial viewing, the tape is generally viewed 3–4 times before a shared perception is arrived at, and, as here, may then be viewed subsequently to reinforce or unpack this perception), and the overall length of the session (approximately 40 min). However, we have also selected this session as typical of the considerable interactional work which can go into the participants arriving at a mutual perception of success and subsequently elucidating the factors that have led to this success. In particular, negotiating a shift from a parental focus on the wider behavioural picture to a small moment of interaction is a recurring feature of these encounters.

As we have previously stated, for the intervention to function successfully, the first step has to be an arrival at this shared perception. Our particular analytic interest is in the ways in which the guider facilitates this perception. Our analysis draws on an ethnomethodological/conversation analytic framework. Talk and aspects of bodily action in the video tapes collected for the intervention, and in the meetings held to discuss these, were transcribed. These tapes were then used to carry out a detailed examination of the interactional character of particular actions and activities (ten Have, 2007). A fundamental principle of conversation analysis is the examination of moment to moment organisation of interaction, where each action is both organised in the light of the prior action and frames the next (Heritage, 1984). As Hindmarsh and Pilnick (2002) note, this resource provides the analyst with the opportunity to focus on members' own displayed orientations to social actions. In this way, we aim to unpack the way in which ‘seeing success’ is produced, managed and unfolds in situ.

As we described above, the VIG intervention's feasibility rests on video recordings of interaction which can be scrutinised in detail. Accordingly, any thorough analysis of the intervention also requires the use of video data. Just as recorded materials provide a resource for the participants to view and review aspects of interaction, so too so they provide this resource for the researcher. While we recognise that these videos provide only one perspective on events, they also provide a continually available resource.

The case

Ewan is an 8 year old boy (at time of recording) with a hearing impairment who is on the autistic spectrum. His family were recruited into the trial at the suggestion of his class teacher in the special educational setting he routinely attends. This teacher, Penny, had received several VIG sessions to support her own practice and had suggested that the family might benefit from VIG. At the initial meeting with the guider, Ewan's mother identified boundaries and boundary setting as an issue in interacting with him. Video recordings have been made of Ewan in his school setting, and the guider has selected two clips from these to view with Ewan's mother and Penny. Real names have been used in this case at the request of the participants, who attributed a significant change to their family life to the intervention resulting in a reduced amount of social care assistance. They have gone on to become advocates for the intervention and have appeared on television and in printed publications with an aim of sharing their story. They did not wish to be anonymised for the purposes of this paper. It is reasonable to assume that their positive experiences with VIG are reflected in this choice and that other participants might have chosen anonymity; this raises broader issues about the researcher/researched relationship and how it might be affected by research outcomes. However, as described above, this case was selected for presentation here on the basis of its typicality rather than its outcome.

The guider in this case is the second author of this paper, who is an academic researcher and a trained VIG practitioner. The first author of this paper had no experience of VIG prior to her being approached to contribute to the evaluation of the process; this approach was made on the basis of her experience of interactional research in other health and social care settings. The analysis presented here was led by the first author, with an acknowledgement that the second author/guider's expertise in the method may otherwise have impacted on their interpretation of the extracts presented here. We reflect on this briefly in the conclusion. The analysis presented here focuses on the first ‘moment of success’ which is presented by the guider to Ewan's mother and his teacher.

The ‘moment of success’

Ewan has been involved in a group task of decorating biscuits, but has left the group table. Penny has subsequently followed him, and has sat on the floor alongside him trying to engage with him while he has played with a construction toy. He then moves away from her towards the open door on a scooter board. The following series of still images show that he pauses in the doorway, removes a notice from the classroom door and begins to play with the blu-tack on the reverse. Penny then moves to sit beside him, and signs to him to put it back, which he does.

Analysis

-

i)

Seeing with reference to the everyday

Anne (Ewan's Mum), Penny (Ewan's teacher) and Deborah (the guider) are all present at the meeting to discuss the clips that Deborah has identified. They sit together on a sofa, facing the TV screen, as the still below illustrates.

Penny has previously viewed and discussed the tape with Deborah on a prior occasion, including the ‘success’ of this moment. The process of discussing the tape in this meeting begins with Deborah introducing the fact that she has picked this clip for its positive qualities. She also states that she has selected it in the knowledge that boundaries and boundary setting have been raised by Anne as an issue in interacting with Ewan, thereby suggesting its wider relevance. She then plays it through, following which both she and Penny turn their gaze directly to Anne to solicit a response (Goodwin, 1980), as the still below shows.

After a pause, Anne responds as follows:

Anne's initial response, then, is to describe what she has seen on the tape. She begins with “he likes blu-tack”, which is a statement drawn from her prior parental knowledge of Ewan rather than producing any analysis of the events she has seen. As Vom Lehn (2006) notes, in his analysis of the general public interacting with museum exhibits, how ordinary people normally look at such things does not reflect professional training, but is framed by their everyday lives. Similarly, in this case, Anne initially sees and describes Ewan's behaviour in the light of her everyday personal experience with him. There is general laughter in response to her initial statement, and Anne then follows this up (line 42) with a description of the action Ewan has undertaken: “you know so is he's putting it on the door for you, yeah”. This statement avoids any evaluation of the situation as a success or otherwise. In response to this (not shown here), Penny supplies more detail of the events that have led up to this point, and then Deborah suggests viewing the tape again now that Anne knows ‘a bit more of the context’. Before this viewing, however, the guider begins to try and shape Anne's perceptual field, through the talk below.

-

ii)

Shaping the vision

Through this talk, Deborah provides a frame through which Anne can look at the interaction, and explicitly refers to this frame in her utterance at lines 91–92: ‘So this is a context where he's opting out basically in the ( ) so just to put it in that frame’. Anne is being encouraged, then, to see the interaction around the notice and the blu-tack against a previous backdrop of ‘opting out’ by Ewan. The clip is then played again, and once again Anne's response is sought through gaze.

-

iii)

Privileging some ‘ways of seeing’ over others

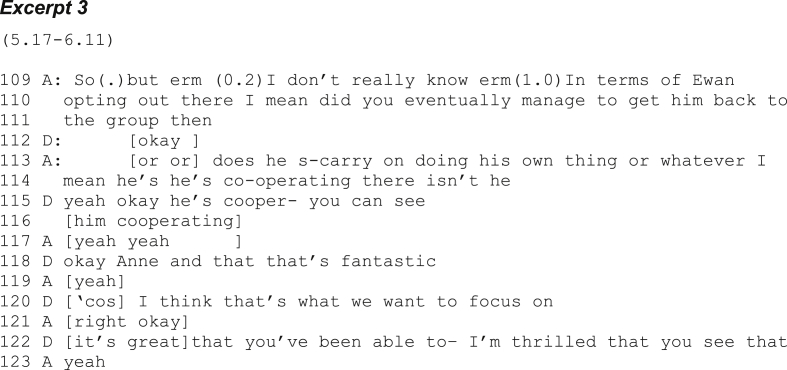

As previously, Anne's initial reaction is to talk about the clip by drawing on what she knows of Ewan in her everyday role as a parent. As an initial response to Deborah's gaze at this point (transcript not included here) she comments ‘That's Ewan’ to illustrate the typicality of events in her personal experience. When she moves back to discussing the tape in its own terms, she focuses at first on the bigger picture. At line 109, aware that Ewan has previously opted out of the biscuit decorating activity, she says:

At the beginning of this utterance, then, Anne appears to be thinking about success in terms of the bigger goal of Ewan returning to the group, and receives a very equivocal ‘okay’ from the guider in response. Proponents of VIG claim that it is unique as an intervention in that it only draws attention to successful elements of communication (James et al., 2013), and so Ewan's failure to return to the group table at this time would not be analysable within the VIG framework. By line 114 Anne has shifted her focus to a much smaller instance of co-operation, over putting the blu-tacked notice back on the door. Deborah subsequently affirms that this is the ‘correct’ way of seeing this instance in this context; indeed her response ‘that's fantastic’ in line 118 followed by “I'm thrilled that you see that” in lines 122–123 suggests that this is not only correct but praiseworthy. The instance of success in this clip then, is what Gross (2009) calls an ‘expert mediated object’, where the expert gaze peripheralizes certain aspects of the interaction (the fact that Ewan does not return to the group) and emphasises others (the fact that Ewan co-operates with Penny by putting the notice back on the door).

-

iv)

Moving from ‘what’ to ‘why’

Having arrived at an agreement that Ewan returning the notice to the door can be viewed by all participants as a moment of co-operation, Anne is then asked if she can watch the tape again to identify what led up to that co-operation through a further viewing. The suggestion is that if Anne can do so, this interactional achievement can be built on in other settings, helping to address Anne's concerns over boundary setting. Just prior to the tape being played again, Penny also ‘helps’ Anne to see, by highlighting the open door to the classroom for her (“'coz it's an open doorway” in line 153, transcript not shown here). Ewan has a tendency to run out of the classroom, and Penny's highlighting of the fact that on this occasion he chooses not to is an example of conditional relevance (Schegloff, 1968), where a first utterance creates an interpretive environment that will be used by participants to analyse whatever occurs after it. The implication is that there must be something to be ‘seen’ in the tape which explains why Ewan does not run. Penny's highlighting here helps with the problems created by non-expert viewing of a dense perceptual field, where the relevance of some aspects over others may need to be emphasised (Goodwin, 1994).

-

iv

a) Highlighting

The tape is then viewed again, but this time the guider invites Anne and Penny to stop it at any point when they ‘see something’. This, then, is another method of highlighting: as well as pointing out particular aspects of an ongoing interaction, which might include contextual features, the interaction can be frozen to demonstrate specific moments in its unfolding. As Hindmarsh et al. (2011) describe, to try and build evidence of understanding at certain points, demonstrators working with dentistry trainees pursue not only verbal confirmation but also adequate visual engagement. Deborah's invitation here provides an opportunity to display just such visual engagement, so that Anne or Penny can show that they can see relevant features. However, in this instance neither Anne nor Penny stop the tape before the end of the clip and the ensuing discussion is reproduced below, prompted again by gaze towards Anne:

Here, then, although Anne can identify what has happened, she still does not feel able to identify why. From lines 199 on she provides an account for this which speaks to the point made above – that she is being asked to look at her child in a way that she does not usually look at him as a parent. However, she elaborates on this by explaining that trying to see ‘differently’ leaves her uncertain about what she is looking for (line 209). In other words, she is not confident that she can see in the required way.

-

iv

b) Invoking a coding scheme

Deborah then returns to the previously obtained mutual agreement over the presence of co-operation, and introduces something she explicitly defines as an object of knowledge – ‘a moment of success’ (line 228), which can be categorised as such because Ewan does not run away. She then produces what in Goodwin's terms would be seen a coding scheme, and a graphic representation of this scheme: a copy of the ‘contact principles’ which shows what those involved in the intervention look for in the tapes.

On handing over the chart, then, Deborah further prompts Anne to the relevant part of it, with the question – “Is co-operation on there anywhere?” According to Cicourel (1964), coding schemes are one systematic practice that is used to transform the world into the categories and events relevant to the work of a particular profession (by way of example, sociologists might use socio-economic status or school truancy officers might use unauthorised absences). In order to make comparisons, events are coded, because once different events are viewed through the same coding scheme, comparisons become possible (Goodwin, 1994). Through use of a scheme, of all the possible ways something could be looked at, the focus is placed on one particular aspect or attribute. In this instance then, what is delineated as relevant according to the contact principles of VIG are the non-verbal ‘tuning in behaviours’ displayed by Ewan and Penny. As Goodwin (1994) describes, and Hindmarsh et al. (2011) elaborate, the ability to see what is relevant is not homogenously distributed, so that a ‘full’ member of a community of practice can be in a position to assess, shape and possibly correct the vision of the emerging participant. By giving a rationale for her choice of clip in the way she does above, Deborah's actions are similar to the ‘modelling’ described by Pomerantz (2003), who describes how those supervising more junior doctors often refrain from explicit teaching in the sense of instructing or correcting, but instead conduct themselves in ways that allow the interns to observe and learn from their conduct. Here, rather than providing a solely objective account of what makes successful communication, Deborah instead gives an account of what led her to pick this clip as a good example. Similarly, in an operating theatre environment, Sanchez Svensson, Heath, and Luff (2009) note how an initial insight made by a surgeon, along with the surgeon's accompanying description, can provide the resources for the trainee to follow and make sense of the procedure and assess how it has transformed the problem with regard to the particulars of this case.

-

v)

The use of expert testimony

Building on the coding scheme and the representation of it supplied by the guider, and the ‘modelling’ of certain features as fundamental to the analysis, Anne's ‘seeing’ of specific elements of behaviour is prompted for, and the tape is viewed again. After this viewing, Anne is able to identify a moment of eye contact between Penny and Ewan, thereby demonstrating (rather than just asserting) that she is now able to ‘see’ in the required way (Hindmarsh et al., 2011). Such demonstrations are critical for the success of VIG, since the guider cannot otherwise be confident that the less experienced party is seeing correctly (Sanchez Svensson et al., 2009). Deborah then asks what else is happening in the interaction, in the extract reproduced below:

Here, Anne firstly identifies Ewan's concentration and happy expression, thereby providing another demonstration to Deborah that she has grasped the specific way of seeing that is required in this setting. She then formulates the idea that it is important to give Ewan a purposeful activity, which Deborah relates to the clip to be shown next (lines 502–503). Previous CA research, for example Heritage and Sefi's (1992) analysis of interactions between health visitors and first time mothers, has demonstrated how tensions can arise in healthcare settings over parental vs professional expertise. One way in which this is manifested in Heritage and Sefi's (1992) data is through the subtle ways in which parents in their study resisted health visitors' unsolicited advice. It may at first seem surprising that, in the sample collected for this study, there is no overt contestation over who knows best what a child's behaviour should be taken to mean. There are also no examples in which a mutual interpretation of success is ultimately resisted, although sometimes this emerges from the viewing of more than one clip. This finding may in part be explained by the fact that VIG guiders are trained not to contest interpretations offered by parents, but to explore or expand them. In addition, where meaning remains ambiguous or where a parent struggles to assign a meaning, the intention of VIG is that guiders aim to focus on the impact of a behaviour or action, rather than the motivation behind it. In this instance, as we have noted, Deborah links Anne's observation to the next clip she has chosen to show, thereby expanding its relevance. Throughout the process of teaching someone how to ‘see’, as Goodwin (1994) notes, there is a growth in intersubjectivity. However, VIG also depends on something else noted by Goodwin – if perceptions are not idiosyncratic views of individuals, but shared professional frameworks, then expert testimony becomes possible. This extract then, is also an example of such expert testimony, with Deborah extrapolating Anne's observation to her professional knowledge of other situations involving Ewan.

-

vi)

Problematizing others' perceptions

Eventually, a mutual perception of success is achieved, as the extract below shows:

In this excerpt, Deborah provides a summary of what Anne has seen in the tape as a proposal to be affirmed. Anne provides this affirmation in Line 554 “I I would say so”, thereby confirming a mutual perception. Interestingly, though, at the end of this extract (line 571) Anne produces the caveat ‘as far as I can see’, which attends to the problem that what is actually being produced here are perceptions of Ewan's own interpretations. Anne has demonstrated that she now knows both how to see and what to look for, i.e. how to relate visible phenomena to the professional categories that are required (Hindmarsh et al., 2011) However, while Anne has successfully learned to see in the same way as Deborah, the relationship between this way of seeing and Ewan's own perceptions remains opaque. This issue is addressed in David Goode's (1994) landmark ethnomethodological study of children who are both deaf and blind. Ordinarily, he argues, we take the achieving of intersubjectivity in interaction for granted, but such an assumption is problematized for those children in his study. He notes how the parents of children with severe disabilities often disagree with professional assessments of the communicative competencies of their children, on the basis that standard assessments can overlook idiosyncratic ways of communicating. As a result, for parents, “Actions are given meaning with respect to a rich background of family knowledge and practice” (Goode, 1994: p. 63), drawing on aspects such as routine, layout of surroundings, bodily orientation etc. Parents, who are usually the people with the most intimate relationship with the child, therefore assume the authority to interpret actions with validity, and then have to make these practices visible to others through guiding their way of seeing. However, this is not to say that all actions become easily interpretable in this way, and just as in Goode's study, where parents suggested that sometimes they did not ‘know’ what a particular action meant or argued that they would need to observe it over an extended period to be certain, in this case Anne openly admits the limits to such intersubjectivity.

-

vii)

Reinforcing

This clip is then viewed 4 more times to revisit and reinforce the aspects of non-verbal behaviour that have been identified as components of this moment of success, before Deborah moves to conclude the discussion:

This concluding section does three things: firstly it emphasises the level of detail at which it is necessary to ‘see’ for VIG to function (‘tiny moments’). This underlines a broader point; the way in which the ability to see the significant features of a scene is tied to the purpose for which it is being viewed. Secondly, it reinforces the collaborative agreement about what constituted success in this clip (line 826). Lastly, it extrapolates from this specific interaction to Anne's broader goals concerning boundary setting and co-operation, to suggest that what they have ‘seen’ today will be helpful in achieving these (lines 833–836). Over the course of this interaction, then, and guided by Deborah and to a lesser extent Penny, Anne has gone from a position where what she ‘saw’ was that Ewan was engaged because he liked blu-tack, through a position where she stated an inability to ‘see’ what was required, to a series of detailed observations on what it is about the contingencies of this specific interaction that is engaging him and a reflection on how this can be translated to other settings. In their process of guiding, Deborah (and to a lesser extent Penny), have drawn on the three key features identified by Goodwin as critical to ‘professional vision’ – practices of highlighting and coding, and the production and use of graphic representations. Through the use of these practices, Deborah has emphasised some aspects of the interaction and peripheralised others, in order to overcome discrepancies between the way in which she and Anne were originally viewing events on the tape.

Conclusions

For VIG to function as an intervention, there needs to be agreement in judgements between guiders, professionals and families about what counts as an instance of success. What we have been interested in exploring in this paper is the way in which the expert guider teaches the non-expert viewer how to see the tape, and how to see relevant events within it. As with Goodwin's analysis of the trial involving the violence against Rodney King, a demonstration is built through active interplay between the coding scheme and the domain of scrutiny to which it is applied. Talk and image together are used together, and the VIG intervention depends on this interplay. What our analysis also highlights are the difficulties parents or carers may have in switching from the parental ‘way of seeing’ that ordinarily informs their observations of their child, to a ‘way of seeing’ consistent with the aims of the intervention. Professional vision is unevenly allocated in this process, hence the need for ‘guidance’ in VIG, and the fact that ultimately, seeing success should be recognised as a contingent accomplishment rather than a mental process. We noted at the outset that one of things VIG does is trains parents to ‘see’ more like professionals, in the sense of becoming more analytic in their observations of children. For this to happen, parents and carers have to become members of a community of practice, in order to accomplish highly specialised activities in collaboration with others (Sanchez Svensson et al., 2009). The way in which they are inducted into this community of practice is through their interaction with the guider.

In terms of the wider relevance of our work, at the beginning of this paper we suggested that unpacking in more detail the process through which ‘seeing’ is accomplished in this setting is critical for the wider use of the VIG intervention. Work in healthcare settings has previously been criticised for its tendency to ‘gloss the tacit practices of in-situ collaboration’ (Hindmarsh & Pilnick, 2002) and we have argued here that information about the process of conducting VIG is critical for its reproducibility and more widespread use, as well as for understanding its apparent success. McConnell's (2002) comprehensive review of interaction-based interventions for children with autism, commissioned by the US National Academy of Science, concludes that many interaction-based interventions are focused on a specific mechanism for creating a specific result (e.g. increasing eye contact), where the integrity of the intervention is easily maintained. Clearly, this is not the case with VIG, which takes a much more wide ranging approach to communication and is therefore less easy to translate into discrete actions or changes. This is a classic problem for the trialability of talk-based interventions, and it is at the heart of the UK Medical Research Council's concern with integrity which we referred to in the introduction; some interventions are much more easily protocolised than others. The danger here, however, is that those interventions which can be seen to be reproduced with a greater degree of fidelity, for example Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, can become seen as the answer because they fit this model rather than because they fit the specific clinical need. What we make here, then, is a case for continued, detailed qualitative research which focuses on the process of interventions in terms of how their guiding principles are enacted, in order to make sure that these fundamental interactional aspects are not lost from consideration. Returning to the review carried out by McConnell, he stresses that to disseminate any kind of intervention, well-contained or otherwise, it needs to be well described, so that information is available on how it is carried out. We hope to have laid the foundations for such a description of process in this paper, and in doing so, shed light on how VIG works in practice. Clinical researchers are sometimes sceptical of single case analyses; however, as Psathas (1992: p. 118) argues in relation to other complex activity systems, “…the analysis of local turns and sequences has to be related to the consideration of the overall structure and cannot be reduced to a restricted set of contiguous turns”. This is because the component sections are interlinked and interdependent. As a result, we would argue that an ethnomethodological/conversation analytic approach has much to offer in unpacking the process of interaction-based clinical interventions more generally.

This study also has implications for practitioners of VIG. As we described earlier, the analysis for this paper was led by the first author, and focused on a case where the second author acted as guider. It is interesting to note that the second author's initial reaction to the analysis was one of dissatisfaction – not with the analysis but with aspects of her practice. In particular, this dissatisfaction was related to instances where she felt that, rather than leading a process of co-construction, she might be seen as re-aligning Anne's perspective to fit her own. This has been fed back into practice in a number of ways: with a stronger focus on leaving space for the parent/carer to formulate their perspectives; with an emphasis on the co-construction of new perspectives arising from the discussion; and through a proposal that the editing and selection of clips for viewing might in future be handed over to the parent/carer. However, one obvious limitation of our current analysis is that we do not have a wider view of practitioners' reflections on the VIG sessions in which they have been involved. Future work could also provide a longitudinal analysis, following families through the VIG process to explore whether and how the interactional contingencies of later sessions might differ from initial ones. Miller and Silverman's (1995) work on HIV counselling as a ‘professional technology’ shows how, over time, those who are being counselled learn to speak in and through ‘therapy talk’, and it would be important to establish whether a similar process occurs with the participants in VIG. Lastly, in terms of the limitations of our work, we return to the point made by Anne herself towards the end of the viewing of the clip; we cannot be certain to what extent the analysis of success presented here accurately represents Ewan's own perceptions of events. This of course is a limitation not just for our research, but also for the practice of VIG.

Finally, we would argue that the findings from this study are relevant not just to practitioners of VIG or to commissioners of intervention-based practice, but also to other practitioners using ‘talking therapies’. VIG focuses on building from existing positive aspects of interaction, and this is in contrast to approaches in professions allied to medicine that are rooted in a deficit model and where the professional is more clearly seen as in possession of the expertise to address the identified deficiency. We have noted that for VIG to function successfully parents need to become co-workers, but the other side to this process is that professionals have to be prepared to relax their exercise of professional authority. Previous conversation analytic work has documented a variety of ways in which patients or clients display resistance to professional viewpoints (e.g. Gill et al., 2010, Heritage and Sefi, 1992). However, as we have described, such resistance is notably absent from our data. This study has a small sample size and therefore we cannot draw definitive conclusions, but we have suggested that this lack of resistance may be linked to the different role that VIG offers to the parent/carer. Unlike in other aspects of healthcare practice, the objective in VIG ought not to be to persuade the patient of the ‘correctness’ of the professional view, but to allow them to become a co-worker in order to explore differences in meaning and facilitate seeing in different ways. As we have shown, this is a difficult interactional task for a practitioner to carry out, and it requires a considerable degree of reflexive practice. However, to embrace this approach successfully requires not only a high level of communicative competency from practitioners, but also a shift in how we consider and conceptualise expertise in practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all those who participated in this study, and particularly Anne, Ewan and Penny for their consent for the images contained in this paper to be reproduced. The study was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research.

Footnotes

The term ‘community of practice’ was first used by Lave and Wenger (1991) to refer to a group of people who share a craft or profession, drawing on their work on how apprentices learn. Communities of practice can evolve naturally, or they can be created specifically with the goal of gaining knowledge.

Appendix 1. The VIG contact principles

Contact principles.

| Clusters | Patterns | Elements |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Initiative and reception | Being attentive | Turning towards someone |

| Looking at someone | ||

| Friendly intonations | ||

| Friendly facial expressions | ||

| Friendly postures | ||

| Attuning oneself | Participation | |

| Nodding | ||

| Naming | ||

| Saying “yes” | ||

| 2 Interaction | Forming a group | Involvement in group |

| Looking around | ||

| Acknowledging reception | ||

| Making turns | Giving and taking turns | |

| Evenly sharing turns | ||

| Co-operation | Joint transactions | |

| Helping one another | ||

| 3 Giving guidance: discussion | Forming opinions | Giving/accepting/exchanging/investigation opinions |

| Giving content | Mentioning/developing/in-depth discussion of subjects | |

| Decision – making | Proposing/accepting/amending agreements | |

| Developing effective learners | Inviting and supporting prediction | |

| Task description/judgment of time needed/approach/difficulties/result | ||

| 4 Giving guidance: conflict management | Naming contradiction | Investigating intentions |

| Resorting contact | Return 1-2-3 | |

| Making transactions | Establishing viewpoints | |

| Comply with rules |

References

- Cicourel A. Free Press; New York: 1964. Method and measurement in sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Clark H. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. Using language. [Google Scholar]

- Fukkink R.G. Video feedback in widescreen: a meta-analysis of family programmes. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:904–916. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill V.T., Pomerantz A., Denvir P. Preemptive resistance: patients' participation in diagnostic sense-making activities. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2010;32(1):1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode D. Temple University Press; Philadelphia: 1994. A world without words: The social construction of children born deaf and blind. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. Restarts, pauses, and the achievement of mutual gaze at turn-beginning. Sociological Inquiry. 1980;50(3–4):272–302. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin C. Professional vision. American Anthropologist. 1994;96(3):606–633. [Google Scholar]

- Gross S. Experts and ‘knowledge that counts’: a study into the world of brain cancer. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(12):1519–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Have P. 2nd ed. SAGE; London: 2007. Doing conversation analysis: A practical guide. [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P., Shiell A., Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7455):1561–1563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J. Polity Press; Cambridge: 1984. Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage J., Sefi S. In: Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings. Drew P., Heritage J., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1992. Dilemmas of advice: aspects of the delivery and reception of advice in interactions between health visitors and first time mothers; pp. 359–419. [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarsh J., Pilnick A. The tacit order of teamwork: collaboration and embodied conduct in anaesthesia. The Sociological Quarterly. 2002;43(2):139–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hindmarsh J., Reynolds P., Dunne S. Exhibiting understanding: the body in apprenticeship. Journal of Pragmatics. 2011;43:489–503. [Google Scholar]

- James D. In: Video interaction guidance. A relationship-based intervention to promote attunement, empathy and wellbeing. Kennedy H., Landor M., Todd L., editors. Jessica Kingsley; London: 2011. Video interaction guidance in the context of childhood hearing impairment: a tool for family centred practice; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- James D., Falck C., Hall A., Phillipson J., McCrossan G. Creating a person-centred culture within the North East Autism Society: preliminary findings. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2013 in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H., Landor M., Todd L., editors. Video interaction guidance: A relationship-based intervention to promote attunement, empathy and well-being. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; London: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koschmann T., LeBaron C. Reconsidering common ground: examining Clark's contribution theory. Proceedings of the 8th European conference on computer supported co-operative work; Helsinki, Finland, 14th–18th September; Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lave J., Wenger E. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. [Google Scholar]

- McConnell S. Interventions to facilitate social interaction for young children with autism: review of available research and recommendations for educational intervention and future research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32(5) doi: 10.1023/a:1020537805154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Research Council . Medical Research Council; London: 2008. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: New guidance. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G., Silverman D. Troubles talk and counseling discourse: a comparative study. The Sociological Quarterly. 1995;36(4):725–747. [Google Scholar]

- Murray L., Trevarthen C. In: Social perception in infants. Field T.M., Fox N.A., editors. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1985. Emotional regulations of interactions between two-month-olds and their mothers; pp. 177–197. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz A. In: Studies in language and social interaction: In honour of Robert Hopper. Glenn P., LeBaron C., Mandelbaum J., editors. Lawrence Erlbaum; New Jersey: 2003. Modeling as a teaching strategy in clinical training: when does it work? pp. 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz A., Fehr B.J., Ende J. When supervising physicians see patients: strategies used in difficult situations. Human Communication Research. 1997;23:589–615. [Google Scholar]

- Psathas G. In: Text in context: Contributions to ethnomethodology. Watson G., Seiler R.M., editors. Sage; London: 1992. The study of extended sequences: the case of the garden lesson. [Google Scholar]

- Sacks H. In: Jefferson G., editor. Vol. 2. Blackwell; Oxford: 1992. (Lectures on conversation). [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Svensson M., Heath C., Luff P. Embedding instruction in practice: contingency and collaboration during surgical training. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2009;31(6):889–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schegloff E.A. Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist. 1968;70:1075–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Trevarthen C. Conversations with a two-month old. New Scientist. 1974;62:230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Vom Lehn D. The body as interactive display: examining bodies in a public exhibition. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2006;28(2):223–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]