Abstract

Objective

Suboptimal management of Parkinson's disease (PD) medication in hospital may lead to avoidable complications. We introduced an in-patient PD unit for those admitted urgently with general medical problems. We explored the effect of the unit on medication management, length of stay and patient experience.

Methods

We conducted a single-center prospective feasibility study. The unit's core features were defined following consultation with patients and professionals: specially trained staff, ready availability of PD drugs, guidelines, and care led by a geriatrician with specialty PD training. Mandatory staff training comprised four 1 h sessions: PD symptoms; medications; therapy; communication and swallowing. Most medication was prescribed using an electronic Prescribing and Administration system (iSOFT) which provided accurate data on time of administration. We compared patient outcomes before and after introduction of the unit.

Results

The general ward care (n = 20) and the Specialist Parkinson's Unit care (n = 24) groups had similar baseline characteristics. On the specialist unit: less Parkinson's medication was omitted (13% vs 20%, p < 0.001); of the medication that was given, more was given on time (64% vs 50%, p < 0.001); median length of stay was shorter (9 days vs 13 days, p = 0.043) and patients' experience of care was better (p = 0.01).

Discussion

If replicated and generalizable to other hospitals, reductions in length of stay would lead to significant cost savings. The apparent improved outcomes with Parkinson's unit care merit further investigation. We hope to test the hypothesis that specialized units are cost-effective and improve patient care using a randomized controlled trial design.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, Hospitalization, Errors, Medication, Length of stay, Specialist unit

Highlights

-

•

We prospectively evaluated a specialist Parkinson's unit for in-patients.

-

•

Patients who received Parkinson's unit care had shorter length of stay.

-

•

Patients who received Parkinson's unit care had better experience of care.

-

•

More Parkinson's medication was given on time.

-

•

Less Parkinson's medication was omitted.

1. Introduction

Parkinson's Disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease in the UK with a prevalence of over 90,000 in 2005 [1]. People with Parkinson's are more likely than their peers to be admitted to hospital [2] with more than 80% being emergency admissions [3]. In the UK, many are admitted to general medical or elderly care wards with falls, pneumonia, urinary tract infection and reduced mobility [4]. However people with Parkinson's are often dissatisfied with the care provided [5] and, in particular, are concerned that omitted or delayed administration of medication may lead to immobility, complications and longer lengths of stay [5], [6], [7], [8]. Staff knowledge of Parkinson's is perceived to be poor [9], [10]. The US National Parkinson Foundation (NPF) has called for educational programmes, recommendations and guidelines for the care of people with Parkinson's admitted to hospital [11]. Few intervention studies have been published [12]. Early consultation by a neurologist and promotion of self-medication have also been recommended [2], [13], [14].

Emergency care on specialist units by appropriately trained staff has proved beneficial for a variety of other conditions such as stroke, myocardial infarction and gastrointestinal bleeding [15], [16], [17], [18]. Whilst, anecdotally, cohorting of PD in-patients has been tried before, we are not aware of a published formal assessment of this approach.

We hypothesized that care on a specialist in-patient Parkinson's Disease Unit (SPDU) would improve both clinically important and patient focused outcomes for people with Parkinson's needing urgent medical care. We used staff and patient focus groups to define the core features of a specialist Parkinson's unit, which was subsequently initiated as an intervention in the context of a busy acute elderly medicine ward. This was evaluated using a prospective study design. Secondary objectives were to explore the feasibility of planning a multi-center randomized controlled trial, and to evaluate and improve the intervention; the staff training program and SPDU processes.

We choose to investigate a specialist unit rather than train all hospital staff because low admission rates on many wards could contribute to decay of staff knowledge.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

We conducted a single-center prospective pilot study. We compared patient outcomes before and after the introduction of the specialist Parkinson's unit. For 3 months (April–June 2012) we recruited patients with Parkinson's admitted urgently to general medical/elderly care wards. In July 2012 we set up the Specialist in-patient Parkinson's Disease Unit and trained the staff on the ward chosen to host the specialist unit. Then (Aug 2012–Feb 2013) we recruited Parkinson's patients going through this specialist unit. The prospectively determined primary outcomes were the proportion of PD medication given on time and length of stay. The study protocol was approved by the hospital's research and development department and a local research ethics committee (NRES East Midlands - Northampton, REC reference 11/EM/0460).

2.2. Setting

The unit was located on an acute 28-bed elderly care ward in a 1100 bed teaching hospital serving a population of 500,000. The number of beds for Parkinson's patients was flexible, typically 2–6. The specially trained staff cared for other patients as well as Parkinson's patients. Ward staffing levels were the same as other elderly care wards in the hospital (see Appendix 1). Most patients were admitted via the medical assessment unit (MAU) where they typically spent less than 24 h.

2.3. The intervention

The core features of the unit were: mandatory staff training; care led by a geriatrician with specialist training in Parkinson's; enhanced stock of Parkinson's drugs (Appendix 2); use of Parkinson's management guidelines; regular multidisciplinary meetings; enhanced access to specialist PD therapists, PD nurse and movement disorder neurologist; and encouragement of self-medicating when appropriate. The mandatory education program comprised 4 one-hour training sessions: PD symptoms and signs; medications, the importance of accurate and timely drug administration, potential medication side effects; therapy, movement and handling, cueing strategies and avoidance of dual tasking; communication and swallowing. Training was in small groups with a trainer. Training videos were developed by the research team.

2.4. Study population

We included only English-speaking patients with PD who needed urgent admission to hospital with a medical problem. We used UK brain bank criteria to confirm the diagnosis of PD [19]. We excluded: patients with parkinsonism due to conditions other than PD; patients whose acute condition required admission to a different specialist unit (e.g. Coronary Care Unit, trauma ward). We tried to recruit consecutive PD admissions. We visited the MAU and elderly care wards daily (weekdays) to identify eligible patients. When the Parkinson's unit was open, Parkinson's patients were sent there if there was a bed available. We sought informed consent from participants. Initially we allowed a minimum of 24 h to read the patient information sheet. Following ethical approval this “cooling off” period was reduced to 4 h (September 2012). We included patients who were confused and lacked capacity to consent after seeking written advice from a consultee, usually the next of kin.

2.5. Data collection

On admission we collected baseline demographic and clinical data. The correct medication schedule was determined by the following hierarchy: report of lucid patient; report of carer; telephone call to family doctor; drug record from last out-patient visit. We examined accuracy of prescription and administration. Most medication was prescribed using an electronic Prescribing and Administration system (iSOFT) allowing the time of administration to be precisely measured. “On time” administration was defined as within 30 min of the scheduled time. The system also recorded reasons medications were omitted. Prescription errors were checked manually (RS). Potential prescription errors included: medication not prescribed; wrong dose; wrong dose frequency; wrong preparation; wrong timing (we allowed 30 min margin of error); prescription of anti-dopaminergic drug. We counted a single missed dose of Parkinson's medication due to non-prescription of medication as a prescription error. Changes made to medication schedules by the treating physician were not considered erroneous if justified in the medical notes.

On admission and discharge we checked hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), Barthel Index for activities of daily living and Lindop Parkinson's Assessment Scale (LPAS) for mobility [20], [21], [22].

A patient experience survey, based on that of Parkinson's UK, was administered by a researcher who was not part of the clinical team. If the survey had not been completed by discharge, it was posted out and self-administered. Carers completed the survey if subjects were unable. In-patient complications were assessed by review of the medical and nursing notes (LB). We used the hospital's patient administration system and the hospital notes to check mortality at 6 months.

We collected data to assess the feasibility of a future randomized controlled trial. We evaluated the staff training with staff knowledge questionnaires before and after each training module and a feedback form after each module.

2.6. Study size

As this was a pilot study, sample size estimations have not been performed. Using hospital patient administration system (PAS) data, we estimated 40–50 eligible patients would be admitted to relevant wards over a 3-month period. We estimated a 50% recruitment rate. All the elderly care wards have high bed occupancy so, despite efforts, not all eligible patients would reach the ward hosting the Parkinson's unit. We estimated 40–50 patients would go through the unit in 7 months and that 20–25 would consent.

2.7. Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata v11. The unit of analysis was the individual patient for all outcomes except the medication data which were analyzed based on individual doses. The distribution of continuous outcomes was assessed using their histograms and results of non-parametric outcomes are presented as median (interquartile range). The continuous outcomes (age, length of stay, number of complications, time from drug prescription to administration, frequency of daily doses, staff knowledge scores), were compared before and after the SPDU using Mann Whitney U test. All categorical variables (demographics, related to medication, mortality, discharge, patient satisfaction questions) were compared between pre and post intervention using Fisher's Exact test. We calculated Spearman's rho to check for correlation between medication outcomes and length of stay.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

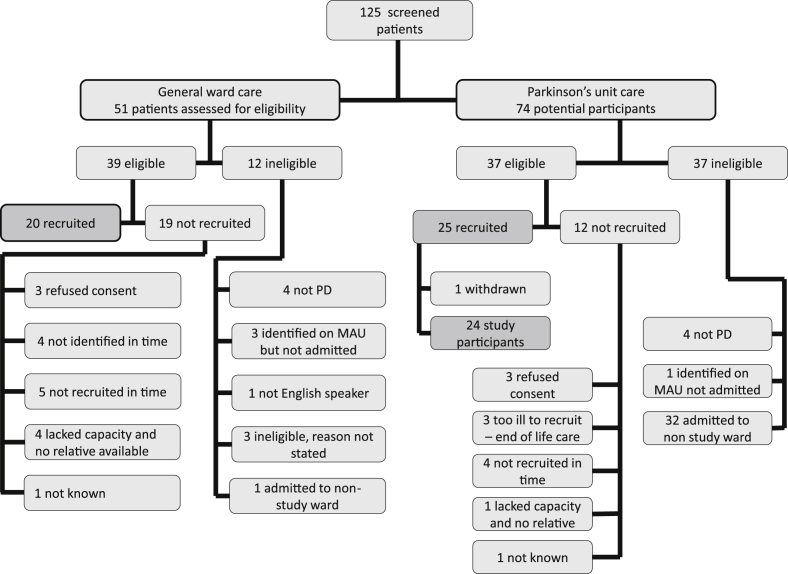

In the general ward care phase of the study we screened 51 patients, 39 were eligible and 20 were recruited: 51% recruitment rate. In the specialist Parkinson's unit phase we screened 74 patients, 37 were eligible and 25 were recruited: 67% recruitment rate (see Fig. 1 for recruitment flowchart). One patient initially recruited was withdrawn as there was an exclusion criterion. Forty-four patients were included in the analysis. The proportion of patients able to sign their own consent forms was: 12 (60%) for general ward care and 11 (46%) for Parkinson's unit care (p = 0.349.)

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient recruitment to the study.

3.2. Baseline descriptive data

The general ward care group and the Specialist Parkinson's Unit care group were well balanced with respect to age, co-morbidity, usual PD medication (Table 1). Patient presenting complaints were often non-specific or multiple but included delirium or psychosis in 25% of each group, and motor problems and falls in 35% (Parkinson's unit) and 33% (general ward). One patient in each group was on antipsychotic medication (quetiapine) before admission and one patient on the Parkinson's unit commenced quetiapine during the admission.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of general ward care patients and specialist Parkinson's unit patients.

| Baseline characteristics | General ward care (n = 20) | Specialist Parkinson's unit care (n = 24) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – years (median – IQR) | 81 (75–84) | 81 (73–84) | 0.611 | |

| Gender | Male | 16 (80%) | 16 (67%) | |

| Female | 4 (20%) | 8 (33%) | 0.498 | |

| Modified Hoehn Yahr stage | 0–2.5 | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | |

| 3 | 14 (70%) | 9 (38%) | ||

| 4 | 3 (15%) | 8 (33%) | ||

| 5 | 3 (15%) | 6 (25%) | 0.160 | |

| Charlson co-morbidity index (median IQR) | 1 (0.25–2.75) | 1 (0.25–1.75) | 0.535 | |

| Disease stage | Diagnostic | 0 | 0 | |

| Maintenance | 4 (20%) | 1 (4%) | ||

| Complex | 15 (75%) | 21 (88%) | ||

| Palliative | 1 (5%) | 2 (8%) | 0.259 | |

| Usual place of residence | Home alone | 6 (30%) | 5 (21%) | |

| Home not alone | 13 (65%) | 13 (54%) | ||

| Residential care | 1 (5%) | 3 (12%) | ||

| Nursing home | 0 (0%) | 3 (13%) | 0.405 | |

| Diagnosis | Lower respiratory tract infection/pneumonia | 5 (25%) | 7 (29%) | |

| Urinary tract infection | 6 (30%) | 7 (29%) | ||

| Other infection | 2 (10%) | 3 (13%) | ||

| Post hypotension | 2 (10%) | 2 (8%) | ||

| PD related/drug effect | 2 (10%) | 4 (17%) | ||

| Other | 3 (15%) | 1 (4%) | 0.859 | |

| Treatment | Patients on l-dopa | 20 (100%) | 24 (100%) | n/a |

| Patients on dopamine agonist | 7 (35%) | 8 (33%) | 1.00 | |

| l-dopa daily dose (mg) – Median (IQR) | 450 (363–638) | 500 (450–600) | 0.223 | |

| Median number of l-dopa doses per day | 4 (3–5) | 4.5 (3–5) | 0.878 | |

| Patients using apomorphine infusion therapy | 0 | 1 (4%) | 1.00 | |

| Patients using deep brain stimulation | 2 (10%) | 1 (4%) | 0.583 | |

Results presented as frequency (%), or as otherwise stated.

3.3. Medication outcomes

On the specialist unit significantly less Parkinson's medication was omitted compared to general ward care (13% vs 20% respectively, p < 0.001, n = 4579 doses); of the Parkinson's medication that was given, significantly more was given on time (64% vs 50%, p < 0.001, n = 3494 doses). Main medication outcomes are shown in Table 2. On the Parkinson's unit and general wards respectively of scheduled PD medication 27 doses (1.7%) vs 98 doses (5.2%) (p < 0.001) were omitted as patients were nil by mouth; 52 (2.4%) vs 91 (4.9%) (p < 0.001) were omitted as doses had not been prescribed; and 54 (2.5%) vs 34 (1.9%) (p = 0.196) were omitted due to absent supply.

Table 2.

Medication outcomes for general ward care patients and specialist Parkinson's unit care.

| Medication outcomes | General ward care | Specialist Parkinson's unit care | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doses (%) of Parkinsons' medication given (n = 4579) | Given | 1660 (77%) | 2080 (86%) | |

| Omitted | 437 (20%) | 329 (13%) | ||

| Not known | 72 (3%) | 1 (1%) | <0.001 | |

| Doses (%) of Parkinsons' medication given early/on timea/late (n = 3494) | Early | 147 (10%) | 217 (10%) | |

| On time | 710 (50%) | 1324 (64%) | ||

| Late | 563 (40%) | 533 (26%) | <0.001 | |

| Doses (%) of l-Dopa medication given early/on time/late (n = 2382) | Early | 101 (10%) | 144 (10%) | |

| On time | 478 (48%) | 917 (66%) | ||

| Late | 413 (42%) | 328 (24%) | <0.001 | |

| Doses of anti-dopaminergic medication given (% of all medication) (n = 9906) | 32 (1%) | 0 | <0.001 | |

| Main reasons for omission of PD medication (% of all scheduled PD medication) (n = 4579) | ||||

| Not prescribed | 91 (4.9%) | 52 (2.4%) | <0.001a | |

| Nil by mouth | 98 (5.2%) | 27 (1.7%) | ||

| Medication not available | 34 (1.9%) | 54 (2.5%) | ||

| Refused by patient | 40 (2.2%) | 28 (1.3%) | ||

| Patient unable to take | 30 (1.7%) | 49 (2.3%) | ||

| Patient off ward | 4 (0.2%) | 1 (0.05%) | ||

| Documented nursing reason | 67 (3.6%) | 73 (3.4%) | ||

| Other reasons | 29 (1.4%) | 17 (0.7%) | ||

| Doses of Parkinson's medication affected by prescription error (% of all scheduled PD medication) (n = 4579) | 171 (7.9%) | 64 (2.7%) | <0.001 | |

‘On time’ administration was defined as within 30 min of the scheduled time. Timeliness analysis was performed on the “given” medication where timed data was available.

The number (%) of patients with any prescription errors was 11 (46%) for the Parkinson's unit and 12 (67%) for the general wards (p = 0.221), (n = 42). The number (%) of doses of PD medication affected by prescription error was lower on the Parkinson's unit: 64 (2.7%) vs 171 (7.9%) (p < 0.001).

The causes of prescription error were similar in the 2 groups. 29% of patients had timing errors, and 21% missed at least one dose of medication as the drug had not been prescribed. Table showing frequencies of types of prescription error is available online: Appendix 3.

3.4. Patient related outcomes

Patient related outcomes such as length of stay, mortality and in-patient complications are shown in Table 3. Median length of stay was significantly shorter on the specialist unit compared to the general wards (9 days vs 13 days respectively, p = 0.043). There was an inverse correlation between length of stay and proportion of Parkinson's medication given on time (r = −0.3351, p = 0.03) but we did not find a correlation between length of stay and proportion of Parkinson's medication omitted (r = 0.297, p = 0.056).

Table 3.

Patient related outcomes for general ward care patients and specialist Parkinson's unit care.

| Patient outcomes | General ward care | Specialist Parkinson's unit care | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay in days – median (IQR) (n = 44) | 13 (9–27) | 9 (5–16) | 0.043 |

| Discharged to usual place of residence (n = 43) | 15 (75%) | 17 (74%) | 1.000 |

| Unplanned readmission within 30 days (n = 38) | 3 (18%) | 6 (26%) | 0.707 |

| In-patient mortality (n = 44) | 2 (10%) | 1 (4%) | 0.583 |

| Mortality at 6 months (n = 44) | 4 (20%) | 3 (13%) | 0.684 |

| In-patient complications | |||

| New pressure sore, (n = 44) | 5 (25%) | 2 (8%) | 0.217 |

| Falls (n = 44) | 7 (35%) | 8 (33%) | 1.000 |

| Delirium (not present on admission) (n = 44) | 4 (20%) | 0 | 0.036 |

| Constipation (n = 44) | 9 (45%) | 11 (46%) | 0.751 |

| Retention of urine requiring catheter (n = 44) | 4 (20%) | 2 (8%) | 0.387 |

| Urinary tract infection (n = 44) | 3 (15%) | 1 (4%) | 0.316 |

| Aspiration pneumonia (n = 44) | 2 (10%) | 1 (4%) | 0.583 |

| Any complication (n = 44) | 15 (75%) | 17 (71%) | 0.757 |

| Median (IQR) complications/patient (n = 44) | 1.5 (0.5–3) | 1 (0–2) | 0.210 |

Results presented as frequency (%), or as otherwise stated.

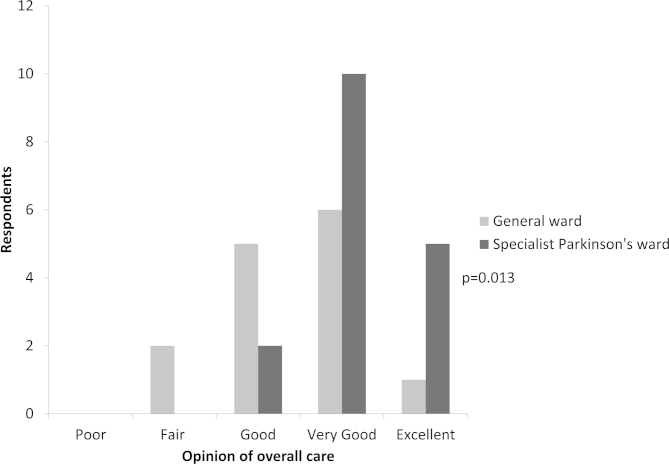

The patient experience questionnaire was completed for 31 of the 41 patients surviving to discharge (76% completion rate). Most patients (65%) had carer help to complete the questionnaire or their carers completed it for them. Overall care was rated significantly better on the specialist unit (p = 0.013, see Appendix 4 online for histogram), Patients' ratings of overall care on the Parkinson's unit and general wards respectively were: “poor” 0, 0; “fair” 0, 2; “good” 2, 5; “very good” 10, 6; “excellent” 5, 1.

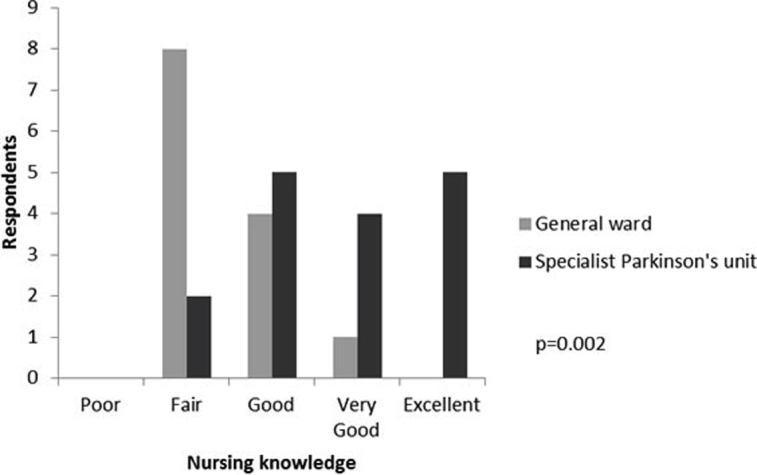

Respondents rated the knowledge of the nursing staff significantly more highly on the specialist Parkinson's unit compared to general ward care (see Appendix 5 online). Also carers rated communication between staff and family significantly more highly on the specialist Parkinson's unit (p = 0.011).

Sixteen (52%) of respondents reported problems due to missed medication: 13 (42%) worse off periods, 9 (29%) anxiety, 8 (26%) prolonged immobility, 5 (16%) pain, and 3 (10%) swallowing problems. Of the respondents who expressed a view, 14/25 (56%), did not think it was important for patients to manage their own medication when in hospital whilst 3 (12%) thought it was very important to do so.

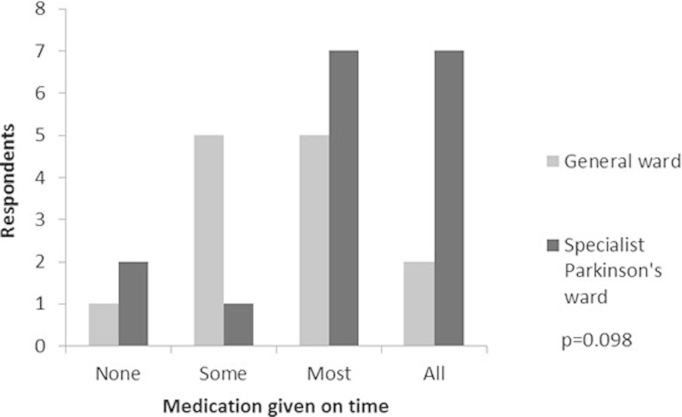

There was no significant difference in respondents' perception of timely medication administration between general ward care and Parkinson's unit but there was a trend towards perception of better performance on the Parkinson's unit (see Appendix 6 online for histogram).

3.5. Core features of the specialist Parkinson's unit

We conducted 28 training sessions (mean 7 per module). 22 training sessions were done in July 2012 and six further sessions took place after July 2012 to capture new staff. Between 52 and 66 staff attended each module. Staff knowledge questionnaires done before and after each training module showed significant improvement in staff knowledge (see Appendix 7 online). Each module received excellent evaluations from staff (median score 7/7 [IQR: 6–7]). Staff self-assessment of ability in relation to key learning objectives showed improvement for all modules.

3.6. Feasibility outcomes

We explored the feasibility of collecting additional data regarding mobility, mood and function. Data collection rates on admission and discharge were: Barthel scale 24 (55%) and 7 (17%), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale 18 (41%) and 8 (20%), Lindop Parkinson's Gait Assessment 6 (14%) and 2 (5%).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first acute admission unit for PD patients that has been designed by staff and patients, initiated in the context of a busy acute medical hospital and evaluated prospectively, collecting data on clinically important outcomes such as electronically measured timing of medication, as well as patient centered outcomes. Our data demonstrate less omitted PD medication, more PD medication given on time, shorter length of stay, and better patient experience on a specialist Parkinson's ward.

The strengths of our study design include: involvement of PD patients and professional staff in the development of the intervention, prospective evaluation of the unit, and electronic data collection on medication timing. The inclusion of both hospital-based objective outcomes and patient-centered subjective outcomes allows different impacts of a complex intervention to be explored. Limitations of our study include: population not blinded to hypotheses being tested, non-randomized trial design, small sample size, Hawthorne effect, and lack of an economic evaluation. The trial design does not exclude the possibility that other factors influenced the observed outcomes. Neither patients nor researchers were blinded to treatment allocation. Although there was no significant difference between groups in time from admission to recruitment (data not shown), greater efforts on the Parkinson's specialist unit to recruit patients early, and the shorter cooling off period prior to consenting, could have influenced the observed reduction in length of stay. Although a formal economic evaluation was not undertaken it appears to be a low cost intervention as no new staff were appointed and no new beds opened. Pharmacy costs from wasted drugs held as stock on the ward were negligible. The main costs related to mandatory staff training (estimate: less than £5000 or $8000). On the other hand, if the shorter length of stay were confirmed, and if it could be generalized to other hospitals, cost savings might be considerable: based on an estimate of 160 PD admissions a year and an estimated cost per patient per day of £225, cost savings to our hospital could be in the region of £144,000.

Specialist Parkinson's units have their own limitations. Pressure on beds in busy acute hospitals means availability of beds on the specialist Parkinson's unit is not guaranteed. In this study 32 potential participants were excluded because they were sent to other wards. Similar problems have, however, been overcome by stroke services. We expect it would be feasible to set up similar units in hospitals of a similar size in the UK. Where there is no geriatrician with appropriate expertise the intervention might be adapted to include daily input from the neurology team.

There is tension between using beds flexibly and potential improved outcomes in specialized beds; we hope our data will contribute usefully to the discussion. Increased attention to PD patients on the ward could have had a negative impact on the other patients; alternatively care of others could have improved as aspects of the training were relevant to many conditions. Patients needing care on other specialist units are excluded, so an alternative approach is needed for these patients. A pro-active Parkinson's outreach service led by a Parkinson's specialist nurse is a promising option [8].

We are aware of only one other published study that reports timeliness of PD medication administration accurately using data from an electronic drug prescription and administration system; this US study reported 8% of medication was omitted and 8% was given late [23]. In a UK-based study of 51 PD patients admitted to surgical departments, 12% of PD medication was omitted [8]. In an observational study of 41 PD patients with hip fractures, reported only in abstract form, a multi-faceted intervention reduced the amount of omitted PD medication but did not reduce complications or length of stay [12]. In all these studies the patient populations differ to ours.

We believe that the inverse correlation between medication given on time and length of hospital stay has not been previously reported using accurately timed medication data. The association is in keeping with subjective, retrospective reports of patients [5], [6], [10]. We know patients' motor function may deteriorate due to medication errors [14], [24]. It may be that worse motor function leads to increased length of stay, or timely Parkinson's medication may be a marker of better overall care. Alternatively the sickest patients may stay longer and these patients may struggle to take their medication. The determinants of length of stay in Parkinson's patients should be researched further.

While our unit administered no contraindicated medication, others report high rates of prescription (7–40%) and administration (2–21%) of anti-dopaminergic medications to PD in-patients [7], [8], [14], [25], [26].

Cognitive impairment (indicated by incapacity to sign consent form) and delirium on admission were common. New onset delirium after admission was lower on the Parkinson's unit. Management and prevention of delirium was covered in the training program. Three of the four new cases of delirium on the general wards were associated with hospital acquired infection. Multiple comparisons and small numbers mean this result should be interpreted with caution.

The proportion of medication omitted due to lack of stock did not improve. Although we had enhanced stock, we did not stock all preparations of all PD drugs. The available stock was not used as flexibly as we had hoped: e.g. doses of modified release medications were omitted rather than a temporary switch to available standard release drugs.

Following the training program, we found improvements in both self-reported knowledge and objective knowledge scores consistent with published reports. Programs that educate nurses about PD can lead to lasting improvements in knowledge [27] and have been associated with improved quality of life and functional outcomes in a residential care setting [28].

In summary we report that, in this pilot study of acutely admitted PD patients, care on a specialist Parkinson's unit resulted in less omitted PD medication, more PD medication given on time, shorter length of stay and better patient experience. The next step is to conduct a larger randomized controlled trial to try to confirm the findings of this pilot study including a health economic evaluation of cost-effectiveness.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by Parkinson's UK (Grant number: K-1105).

We have no financial disclosures pertinent to this research. Full financial disclosures are available as online supplement.

We acknowledge the help and advice of Dr Andrew Fogarty who commented on the protocol and manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.09.015.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Dorsey E.R., Constantinescu R., Thompson J.P., Biglan K.M., Holloway R.G., Kieburtz K. Projected number of people with Parkinson disease in the most populous nations, 2005 through 2030. Neurology. 2007;68(5):384–386. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247740.47667.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerlach O.H.H., Winogrodzka A., Weber W.E.J. Clinical problems in the hospitalised Parkinson's disease patient: systematic review. Mov Disord. 2011;26:197–208. doi: 10.1002/mds.23449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health Service . 2006. Hospital admissions data for England 2005/6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodford H., Walker R. Emergency hospital admissions in idiopathic Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1104–1108. doi: 10.1002/mds.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barber M., Stewart D., Grosset D., MacPhee G. Patient and carer perception of the management of Parkinson's disease after surgery. Age Ageing. 2001;30:171–172. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.2.171-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerlach O.H., Broen M.P., van Domburg P.H., Vermeij A.J., Weber W.E. Deterioration of Parkinson's disease during hospitalization: survey of 684 patients. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-13. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2377/12/13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magdalinou K.N., Martin A., Kessel B. Prescribing medications in Parkinson's disease (PD) patients during acute admissions to a District General Hospital. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13:539–540. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derry P.C., Shah K.J., Caie L., Counsell C.E. Medication management in people with Parkinson's disease during surgical admissions. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:334–337. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.080432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buetow S., Henshaw J., Bryant L., O'Sullivan D. Medication timing errors for Parkinson's disease: perspectives held by caregivers and people with Parkinson's disease in New Zealand. Parkinson's Dis. 2010;2010:1–6. doi: 10.4061/2010/432983. http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2010/432983 Article ID 432983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parkinson's Disease Society . 2008. Life with Parkinson's today - room for improvement. Report. London. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aminoff M.J., Christine C.W., Friedman J.H., Chou K.L., Lyons K.E., Pahwa R. Management of the hospitalized patient with Parkinson's disease: current state of the field and need for guidelines. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17(3):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowen J., Ganapathy R., Guy K., Chatterjee A.K. A multidisciplinary approach improves medication administration in patients with Parkinson's disease and neck of femur fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(S196):0002–8614. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta S., Vankleunen J.P., Booth R.E., Lotke P.A., Lonner J.H. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with Parkinson's disease: impact of early postoperative neurologic intervention. Am J Orthop. 2008;37:513–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerlach O.H., Broen M.P., Weber W.E. Motor outcomes during hospitalization in Parkinson's disease patients: a prospective study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2013;19:737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moore S., Gemmell I., Almond S., Buchan I., Osman I., Glover A. Impact of specialist care on clinical outcomes for medical emergencies. Clin Med. 2006;6(3):286–293. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-3-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration Collaborative systematic review of the randomised trials of organised inpatient (stroke unit) care after stroke. Br Med J. 1997;314:1151–1159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanderson J.D., Taylor R.F., Pugh S., Vicary F.R. Specialized gastrointestinal units for the management of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:654–656. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.778.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nash I.S., Nash D.B., Fuster V. Do cardiologists do it better? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:475–486. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00528-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes A.J., Ben-Shlomo Y., Daniel S.E., Lees A.J. UK Parkinson's disease society brain bank clinical diagnostic criteria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1992;55:181–184. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston M., Pollard B., Hennessey P. Construct validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale with clinical populations. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:579–584. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahoney F.I., Barthel D. Functional evaluation: the barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearson M.J., Lindop F.A., Mockett S.P., Saunders L. Validity and inter-rater reliability of the lindop Parkinson's disease mobility assessment: a preliminary study. Physiotherapy. 2009;95:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hou J.G., Wu L.J., Moore S., Ward C., York M., Atassi F. Assessment of appropriate medication administration for hospitalized patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(4):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grosset D., Antonini A., Canesi M., Pezzoli G., Lees A., Shaw K. Adherence to antiparkinson medication in a multicenter European study. Mov Disord. 2009;24:826–832. doi: 10.1002/mds.22112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domingo-Echaburu S., Lertxundi U., Gonzalo-Olazabal E., Peral-Aguirregoitia J., Pena-Bandres I. Inappropriate antidopaminergic drug use in Parkinson's disease inpatients. Curr Drug Ther. 2012;7:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan L.C., Tan A.K., Tjia H.T. The profile of hospitalised patients with Parkinson's disease. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1998;27:808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chenoweth L., Sheriff J., McAnally L., Tait F. Impact of the Parkinson's disease medication protocol program on nurses' knowledge and management of Parkinson's disease medicines in acute and aged care settings. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Makoutonina M., Iansek R., Simpson P. Optimizing care of residents with Parkinsonism in supervised facilities. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2010;16:351–355. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.