Abstract

Dyshidrosiform pemphigoid is a rare variant of bullous pemphigoid localized to the hands and feet whose characteristic subepidermal blisters develop as a result of binding of the IgG autoantibodies to intracellular plaque and extracellular face of the hemidesmosome recognizing a 230-kDa plakin molecule (BP230, BPAg1or BPAg1e) and a 180-kDa transmembrane protein. Neurodegenerative processes (viz., stroke, dementia, Parkinsonism, epilepsy, etc) uncover BPAg1-n, an alternatively spliced form of BPAg1-e that stabilizes the cytoskeleton of sensory neurons, generating autoantibodies that may subsequently lead to BP by cross-reacting with BPAg1-e. We present a patient with Parkinsonism who later developed blisters, erosions and crusts localized to the palms and soles, confirmed histopathologically as bullous pemphigoid. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first case report from India wherein Parkinsonism-generated autoantibodies led to the development of dyshidrosiform pemphigoid due to their cross-reactivity with BPAg1-e.

Keywords: Bullous pemphigoid, dyshidrosiform pemphigoid, epithelial bullous pemphigoid antigen 1, neurological disorders, neuronal bullous pemphigoid antigen 1

INTRODUCTION

Bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune bullous disorder due to antibodies against hemidesmosomal proteins namely BP antigen 1 (BPAg1) and BP antigen 2 (BPAg2), usually affects the elderly, predominantly as flexural bullae over limbs and abdomen.[1] Dyshidrosiform pemphigoid (DP), a rare variant of localized BP, presents over the palms and soles akin to dyshidrosiform dermatitis.[2] An association between neurological diseases (stroke, dementia, Parkinsonism, epilepsy, etc.) and subsequent development of BP may exist, as autoantibodies against the exposed neuronal antigen (BPAg1-n), an alternating spliced form of epithelial BPAg1 (BPAg1-e) that stabilizes the cytoskeleton of sensory neurons, may cross-react with the epithelial antigen (BPAg1-e).[3,4] Herein we report the development of DP in a 91-year-old female patient of Parkinsonism, enunciating its pathogenesis.

CASE REPORT

A debilitated, non-ambulatory female aged 91 years, known case of Parkinsonism since 2 years, presented to us with the history of appearance of multiple blisters over palms and soles since one month. Local itching and burning preceded their onset. There was no significant antecedent drug intake. There was no icterus, pallor, lymphadenopathy, clubbing or organomegaly. Neurological examination revealed mask like facies, glabellar tap, pill rolling tremors of the right hand, cogwheel rigidity and hypertonia of limbs. Lateral and palmoplantar aspects of hands [Figure 1] and feet [Figure 2] showed dark brown encrusted erosions and a few tense clear bullae with negative Nikolsky- and Asboe-Hansen signs. Histopathological examination findings of subepidermal bulla containing eosinophilic infiltrate [Figure 3] in the lesional skin and IgG at dermoepidermal junction (DEJ) on direct immunofluorescense [Figure 4] confirmed our clinical suspicion of BP. Peripheral blood smear and ultrasonography abdomen were normal. Advanced imaging studies could not be carried out due to kyphoscoliosis, chest X-ray evidence of scoliosis to the right and her confinement to the wheelchair. Advanced confirmational studies viz., immunoblot/immunoprecipitation could not be afforded by the patient. Treatment with tetracycline, nicotinamide and dapsone showed appreciable improvement after a fortnight. She insisted to go home on discharge and passed away a month later due to gastrointestinal bleeding.

Figure 1.

Healed lesions with hyperpigmentation in between fingers of right hand and over right palm

Figure 2.

Bullae over the sole of the left foot

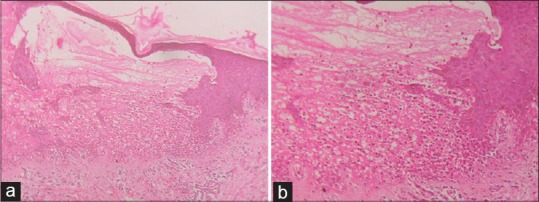

Figure 3a.

Lesional skin biopsy showing (a) Subepidermal blisters predominantly containing eosinophilic infiltrates (H and E, ×10), (b) eosinophilic infiltrates (H and E, ×40)

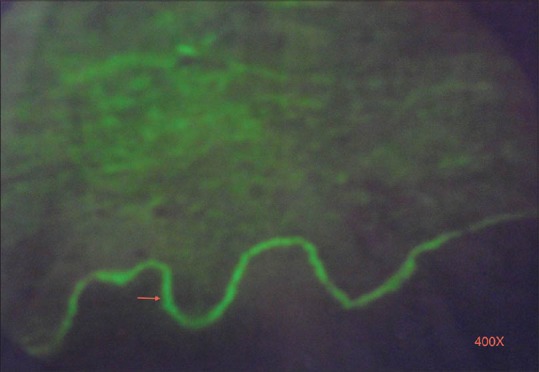

Figure 4.

Direct immunofluorescence showing linear deposition of IgG in the basement membrane zone (×400)

DISCUSSION

BP, a subepidermal immunobullous dermatosis, has characteristic linear immune deposits of IgG and C3 at the DEJ. The median age of onset is 65 years and incidence ranges between 0.2 and 3 per 100,000 person years.[5]

Classic BP has generalized large, tense blisters with serous or hemorrhagic fluid arising over normal or erythematous skin, predominantly of flexures, abdomen and thighs. While some patients develop blisters after persistent urticarial lesions, others continue to have urticarial lesions only. Lesions heal spontaneously with hyperpigmentation and without scarring.[4] Several variants (viz., vesicular, vegetative, nodular, localized, dyshidrosiform, erythrodermic, etc.) have been described. Vesicular BP shows groups of small tense blisters on an urticarial or erythematous base. Uncommonly, BP presents as intertriginous vegetative plaques. Rarely, nodules resembling prurigo nodularis and blisters originating on normal-appearing or nodular skin indicate nodular BP.[4,5] Infrequently, the variant of localized BP occurs mainly over the legs, though it has been documented over oral and vulvar regions[1] and also following radiotherapy, surgery, burns, etc.

DP, first described by Levine et al. in 1979, is a rare form of localized BP similar to dyshidrosiform dermatitis. It may remain localized to palms and/or soles for years or may become generalized. The mechanism of localization is still unclear.[2]

At the molecular level, BP is characterized by the tissue-bound and circulating IgG autoantibodies against the two hemidesmosomal antigens, BPAg1 (230 kD) intracellularly and BPAg2 (180 kD or type XVII collagen) the transmembrane protein. This IgG disrupts DEJ, by activating complement and causing inflammation and may also directly interfere with the function of hemidesmosomes.[6] BPAg1-e, the epithelial isoform that anchors intermediate filaments to the hemidesmosomes and BPAg1-n, the neuronal isoform that organizes the neuronal cytoskeleton by binding the neurofilament triplet proteins to the microfilaments,[4,7] share high homology. BPAg1-n, usually protected from antibody recognition, might get uncovered during an acute phase of neurodegeneration, generating autoantibodies that can cause cutaneous damage due to cross-reactivity.[8]

Neurological diseases and BP are more common with increasing age. Multiple microtrauma, microvascular pathology or local inflammation seen on magnetic resonance imaging during the acute phase of neurodegenerative diseases may abolish the brain's immunological privilege’ due to the damaged blood-brain barrier. The peripheral immune system might activate itself against the neuronal antigens magnifying damage to the central nervous system. This hypothesis was also supported by the association between the dystonin gene, encoding for the neuronal isoform of BPAg1 and degenerative neurological disease in mice.[9] Alternatively, factors such as immobility and drugs associated with the management of previous neurological disorders may trigger BP.[3,10]

A recent study reported an associated occurrence of BP in 21% cases of neurological disorder (8% stroke, 7% dementia, 3% Parkinsonism, 2% epilepsy and 1% multiple sclerosis) of more than a year's duration; however, in none of the cases BP preceded a neurological disorder thereby proving that the exposure of the neuronal antigen can be a causative factor in the later onset of BP in these patients.[3] Hence, novel interventions (e.g. targeting BPAg1-n) based on the immune association between neurodegeneration and BP may become available in the future.[3]

To the best of our knowledge, none of the earlier described 21 cases of DP[2] in the world literature have been from India; our present case of DP in an extremely aged female of Parkinsonism – first such from India - emphasizes the imperative requirement of a thorough search for any underlying neurodegenerative disease in all elderly patients of BP.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmidt E, Benoit S, Bröcker EB. Bullous pemphigoid with localized umbilical involvement. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:419–20. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupi F, Masini C, Ruffelli M, Puddu P, Cianchini G. Dyshidrosiform palmoplantar pemphigoid in a young man: Response to dapsone. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:80–1. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langan SM, Groves RW, West J. The relationship between neurological disease and bullous pemphigoid: A population-based case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:631–6. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culton DA, Liu Z, Diaz LA. Bullous pemphigoid. In: Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. pp. 608–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandpur S, Verma P. Bullous pemphigoid. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:450–5. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.82398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh SR, Hogg D, Mydlarski PR. Bullous pemphigoid: From bench to bedside. Drugs. 2005;65:905–26. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung CL, Sun D, Liem RK. The intermediate filament protein peripherin is the specific interaction partner of mouse BPAG1-n (dystonin) in neurons. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:435–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li L, Chen J, Wang B, Yao Y, Zuo Y. Sera from patients with bullous pemphigoid (BP) associated with neurological diseases recognized BP antigen 1 in the skin and brain. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1343–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown A, Bernier G, Mathieu M, Rossant J, Kothary R. The mouse dystonia musculorum gene is a neural isoform of bullous pemphigoid antigen 1. Nat Genet. 1995;10:301–6. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Li L, Chen J, Zeng Y, Xu H, Song Y, et al. Sera of elderly bullous pemphigoid patients with associated neurological diseases recognize bullous pemphigoid antigens in the human brain. Dermatology. 2011;57:211–6. doi: 10.1159/000315393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]