Abstract

Malignant melanoma (MM) of soft tissue, also called clear cell sarcoma (CCS) of tendons and aponeuroses, derives from the neural crest. CCS is similar morphologically to MM but has no precursor skin lesion, and instead, has a characteristic chromosomal translocation. Prognosis is related to the tumor size. Early recognition and initial radical surgery is the key to a favorable outcome. The tumor has to be differentiated from other benign and malignant lesions of the soft tissues, such as fibrosarcoma. The demonstration of melanin and a positive immunohistochemical reaction for S-100 protein and HMB-45 can assist in the differential diagnosis. We report the case of a 58-year-old woman with CCS arising from the soft tissue of her little finger.

Keywords: Clear cell sarcoma, finger, hand, HMB-45, poor prognosis, S-100 protein

INTRODUCTION

Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue (CCSST) was originally described by Dr Franz Enzinger in 1965. He recognized it as a distinct entity of tendons and aponeuroses in young adults, with a propensity to the lower extremity and localized rarely in the intestine, and described its morphological similarity to malignant melanoma (MM).[1,2] This soft tissue neoplasm is thought to derive from neural crest cells. The main characteristic of CCS is its immunohistochemical, morphological, and ultrastructural similarity to MM.[3] Because of these melanocytic features, its distinction from MM may be difficult.[4,5] We present a case of CCS on the finger due to its rarity.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old female presented with a painful lesion on the fifth finger of her right hand of two months duration. Dermatological examination of the finger revealed an ulcerated lesion associated with ulcers, measuring approximately 6 × 8 cm, with increase in vascularity [Figure 1]. Her personal and family history was unremarkable, and there was no personal or family history of cutaneous malignancy. Her vital signs were stable and the systemic examination was normal. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. Complete blood count, blood biochemistry, tumor markers, and abdominopelvic ultrasonography were normal. Radio-imaging revealed no bone pathology.

Figure 1.

Fifth finger revealing an ulcerated lesion measuring approximately 6 × 8 cm

The patient was referred to the Department of Plastic Surgery and Reconstruction for excision of the lesion, with a presumptive diagnosis including fibrosarcoma, malignant edema, CCS, tenosynovial sarcoma, and angiosarcoma.

The lesion was excised by plastic surgeons. The histopathological findings were as follows: Microscopically, the tumor was composed of solid nests of spindle cells delineated by fibrous septa. Tumor cells were mostly spindle-shaped or polygonal with clear cytoplasm and displayed minimal cytologic atypia. Immunohistochemically, tumor cells showed diffuse and intense positivity for both anti-S-100 and anti-HMB-45 antibodies [Figures 2 and 3]. The case showed uniform nests and fascicles of pale spindled or slightly epithelioid cells with finely granular eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm. Based on the histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed as CCS, and the fifth finger of the right hand was amputated [Figure 4]. The magnetic resonance imaging with contrast demonstrated a metastatic lung mass. Despite the patient's referral to the Oncology Department, she died in a very short period.

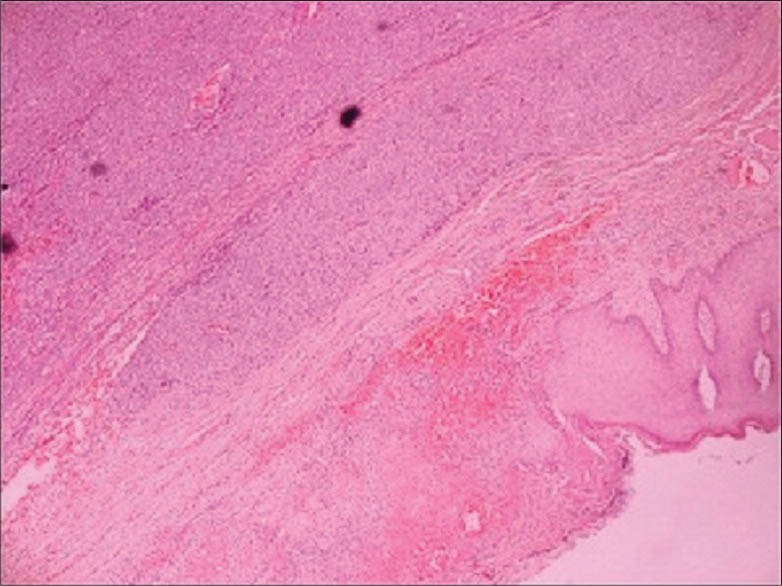

Figure 2.

Tumor composed of solid nests of spindle cells delineated by fibrous septa (H and E, ×100)

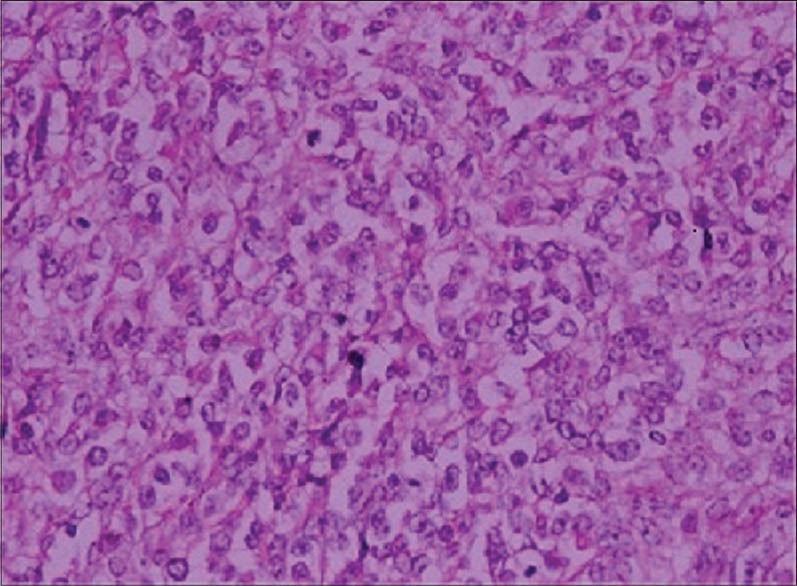

Figure 3.

Tumor cells showing diffuse and intense positivity for both anti-S-100 and anti-HMB-45 antibodies (×100)

Figure 4.

Right hand with fifth finger amputated

DISCUSSION

CCSST is rare, accounting for approximately 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas. Primary CCS usually occurs in deeper soft tissues, in association with fascia, tendons, or aponeuroses. It typically involves the extremities, especially tendons and aponeuroses of the foot and ankle.[1,3] CCSST is rarely localized in the intestine, and the natural history of this tumor is not yet clear. About 40% of cases are deep-seated in the foot and ankle, with no skin association.[2,6] In our case, the mass was localized to fifth finger of right hand.

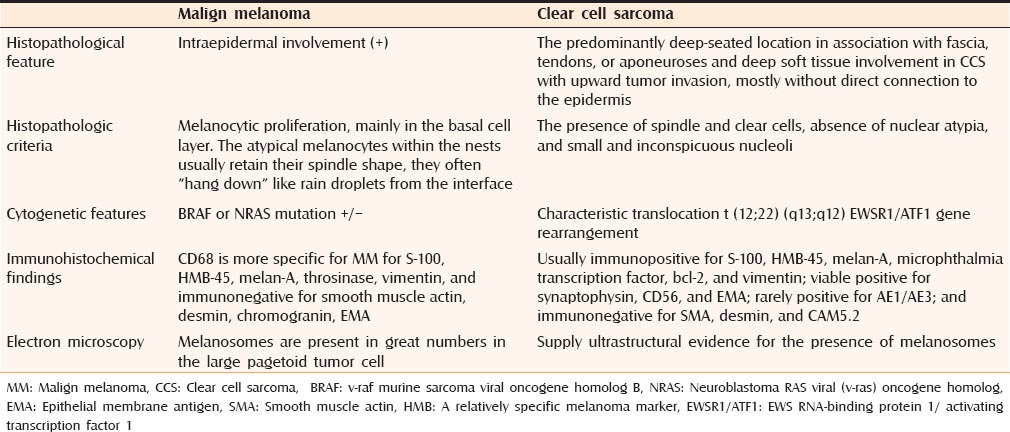

The differential diagnosis of a tumor located in close proximity to tendons and aponeuroses in an extremity includes the recently described paraganglioma-like dermal melanocytic tumor, clear cell myomelanocytic tumor, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, monophasic synovial sarcoma, deep-seated epithelioid sarcoma, adult fibrosarcoma, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma, and metastatic MM.[7] The distinction between CCS and MM should be done [Table 1].

Table 1.

The distinction between CCS and malignant melanoma

Histopathologic criteria that support the classification of CCS as a separate entity include the presence of spindle and clear cells, absence of nuclear atypia, and small and inconspicuous nucleoli. MM is usually accompanied by an intraepidermal component and the lesion of our patient presented in dermal localization. Although it is not necessary, lack of pigmentation is expected in MM.

Junctional activity can be observed in the tumor, with nests of proliferating melanocytic cells showing cytologic atypia in the basal layer.[2,7] The immunohistochemical study plays an important role in the differentiation. CCSST is usually immunopositive for S-100, HMB-45, melan-A, microphthalmia transcription factor, bcl-2, and vimentin; viable positive for synaptophysin, CD56, and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA); rarely positive for AE1/AE3; and immunonegative for smooth muscle actin (SMA), desmin, and CAM5.2.[6] In our case, immunohistochemically, tumor cells showed diffuse and intense positivity for both anti-S-100 and anti-HMB-45 antibodies.

The two melanoma-specific antibodies Melan-A and MART-1 were negative in our case. These are expected to be positive in MM. Besides, CD99 and synaptophysin were found positive that favor the diagnosis of CCS.

Morphologically, the uniform nature of the tumor cells, lack of pagetoid spread, and presence of scattered wreath-like multinucleated cells are features which should prompt consideration of a diagnosis of CCS over a melanoma.

CCS prognosis depends on the size of the mass and metastasis remains very aggressive, as observed in our patient. Poor prognosis is associated with tumor size larger than 5 cm and presence of necrosis, metastasis, and local recurrence. The survival rate for CCSST at 5, 10, and 20 years was reported as 67, 33, and 10%, respectively, in one study.[7] In our case, the diameter of tumor was larger than 5 cm so that the duration of survival was very low.

Treatment of CCSST involves wide excision of the tumor as soon as the diagnosis is established. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy have not been shown to be of benefit. Poor prognosis is associated with tumor size larger than 5 cm and presence of necrosis, metastasis, and local recurrence.[8]

In conclusion, CCSST is a rare, highly malignant soft tissue tumor, and occurs most commonly in the extremities; the majority of patients are young women. When a fast-growing (i.e., a few months) and rapidly ulcerating, large nodular lesion is detected in a tendon or aponeurosis of a young- to middle-aged patient, it should always raise suspicion of CCSST.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Enzinger FM. Clear-cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. An analysis of 21 cases. Cancer. 1965;18:1163–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196509)18:9<1163::aid-cncr2820180916>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lasithiotakis K, Protonotarios A, Lazarou V, Tzardi M, Chalkiadakis G. Clear cell sarcoma of the jejunum: A case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hantschke M, Mentzel T, Rutten A, Palmedo G, Calonje E, Lazar AJ, et al. Cutaneous clear cell sarcoma: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 12 cases emphasizing its distinction form dermal melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:216–22. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181c7d8b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowson A, Magro C, Mihm MC., Jr Unusual histologic and clinical variants of melanoma: Implications for therapy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9:403–10. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, Mandahl N. Absence of mutations of the BRAF gene in malignant melanoma of soft parts (clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses) Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;156:74–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hisaoka M, Ishida T, Kuo TT, Matsuyama A, Imamura T, Nishida K, et al. Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 33 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:452–60. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31814b18fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dim DC, Cooley LD, Miranda RN. Clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses: A review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:152–6. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-152-CCSOTA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones RL, Constantinidou A, Thway K, Ashley S, Scurr M, Al-Muderis O, et al. Chemotherapy in clear cell sarcoma. Med Oncol. 2011;28:859–63. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]