Abstract

Despite decades of research, recognition and treatment of mental illness and its co-morbidities still remain a significant public health problem in the United States. Ethnic minorities are identified as a population that is vulnerable to mental health disparities and face unique challenges pertaining to mental health care. Psychiatric illness is associated with great physical, emotional, functional, and societal burden. The primary health care setting may be a promising venue for screening, assessment, and treatment of mental illnesses for ethnic minority populations. We propose a comprehensive, innovative, culturally centered integrated care model to address the complexities within the health care system, from the individual level, that includes provider and patient factors, to the system level, which include practice culture and system functionality issues. Our multi-disciplinary investigative team acknowledges the importance of providing culturally tailored integrative healthcare to holistically concentrate on physical, mental, emotional, and behavioral problems among ethnic minorities in a primary care setting. It is our intention that the proposed model will be useful for health practitioners, contribute to the reduction of mental health disparities, and promote better mental health and well-being for ethnic minority individuals, families, and communities.

Keywords: Mental Health Disparities, Culturally-Centered Integrative Care, Ethnic Minorities, African Americans

Introduction

Since the release of the landmark report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health (Smedley et al., 2003), mounting evidence of a myriad of issues concerning access to healthcare services, quality of care received, and improvement in health outcomes among different groups continues to build. Furthermore, since 2003, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has released its annual National Healthcare Disparities Report (AHRQ, 2012) and recently indicated that although the United States health care system is designed to improve the physical and mental well-being of all Americans by preventing, diagnosing, and treating illness and by supporting optimal functioning. Health disparities continue to exist and our system of health care distributes services inefficiently and unevenly across populations. In 2013, approximately 10 years after the IOM Unequal Treatment report, similar multi-dimensional problems still exist which continues to heighten the conundrum for health and mental health providers in search of promising approaches to reduce and ultimately eliminate disparities in health. Addressing the multi-faceted health and mental health needs of the United States population is a complex issue that warrants attention from clinicians, researchers, scientists, public health professionals, and policy makers that can offer unique perspectives and strategies to support efforts for greater well-being among individuals. With growing diversity concerning various ethnicities and nationalities; and with significant changes in the constellation of multiple of risk factors that can influence health and mental health outcomes, it is imperative that we delineate strategic clinic-based efforts, focused community-based programs, and innovative multi-disciplinary research that include an examination of evidence-based models that may improve individuals’ longevity and quality of life. These issues have particular relevance for vulnerable and high risk populations, such as many racial/ethnic minorities, including African Americans which have the lowest life expectancy in the United States.

Despite decades of research, recognition and treatment of mental illness and its co-morbidities still remain a significant public health problem in the United States. According to data from the National Institute of Mental Health (2008) approximately 57.7 million adults in the United States suffer from a diagnosable mental disorder each year, suggesting that many individuals endure deleterious functioning in various areas of their lives. Moreover, major depression is one of the most common mental health problems in the United States affecting approximately 14.8 million adults; and women ages 18 to 45 years old account for the largest proportion of functional impairment of this group (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration [SAMHSA], 2010). In a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, Mental Illness Surveillance among Adults in the United States (CDC, 2011), it was recommended that efforts to monitor mental illnesses and establish better coping approaches for those with mental disorders should be increased. This notion is further reinforced by (1) Healthy People 2020 and one of its goals which is to “improve mental health through prevention and by ensuring access to appropriate, quality mental health services” (US Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2010); and (2) initiatives elucidated in the National Institute of Health (NIH), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) 2008 strategic plan.

Nationwide attention was focused on racial/ethnic disparities in mental health services and outcomes in the Surgeon General landmark supplemental report, Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity (DHHS, 2001). This report documented that minorities receive lower quality mental health care in general than Caucasians and there are still wide disparities in mental health services for African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans and American Indians/Alaskan Natives. Moreover, Holden and Xanthos (2009) reported that African Americans experience more mental health disadvantages relative to Caucasian Americans with respect to financial barriers, barriers to help seeking, and poorer quality services. Research among low income African Americans indicated mental health treatment seeking barriers included poor access to care, stigma, and lack of awareness about mental illness (Gonzales, 2010; Ward et al., 2009). Additionally, ethnic minorities’ failure to perceive the need for care, partially account for the low rates of care for depression among this population (Nadeem et al., 2009).

There are many factors that influence these disparities, including social determinants of health such as poor education, lack of health insurance coverage, economic challenges, and impoverished environmental conditions (Treadwell, Xanthos, & Holden, 2012). Important considerations for reducing health disparities may include implementation, monitoring, and tracking of local, state and national health policies; improving access to comprehensive, integrated and patient-centered quality healthcare; and promotion of culturally-centered prevention and intervention approaches for vulnerable populations. With recent implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) (USDHHS, 2010) there is promise for emphasis on better approaches for integrated systems of care for Americans in general, and vulnerable populations in particular. In particular, the ACA encourages better integration of health systems and processes utilizing approaches that minimizes duplication of services and more streamlined comprehensive care.

Our multi-disciplinary investigative team acknowledges the absence of strong evidence about the effectiveness of culturally centered integrated healthcare models to address health and mental health issues for ethnically and culturally diverse patients (Tucker et al., 2011; Cross et al., 1989). However, several observations that are evident in the research literature and enjoy widespread agreement, support the promise of further investigation: 1) there is a relationship between patient experiences within health care settings and health care provider behaviors (Shim et al., 2013; Tucker et al., 2011) that may differ with regard to cultural sensitivity, 2) increased ethnic and cultural diversity in the health care and behavioral health care workforce is sorely needed (National Research Council, 2001; Rust et al., 2006), and 3) ethnic minorities are more likely to report behavioral health problems in primary settings and less likely to receive care in outpatient mental health settings (Cooper et al., 2003; Snowden, 2001). This manuscript seeks to add to the limited body of literature on this topic to help address the treatment of mental disorders among ethnic minorities in primary healthcare settings.

We acknowledge that ethnic minorities are not a homogenous population; rather it is a population that encompasses many sub-cultures and ethnic identities based on migration patterns to the United States, regional distinctions within the United States, varying dialects, and differing socio-cultural norms, education levels, and experiences. However, we propose to encapsulate the term ethnic minorities to represent individuals that reside in the United States with historical and ancestral roots across African, Latin, and Native American Diasporas.

Mental Health Disparities among Ethnic Minorities

As part of its definition of mental health disparities, CDC highlighted differences between populations with respect to their accessibility, quality, and outcomes of mental healthcare as a major component of disparities (Safron et al., 2009). It has been further specified that disparities are inequalities that are potentially unexpected, undesirable, and problematic (Hurt et al., 2012; Gonzalez & Papadopoulos, 2010). The supplement to the Surgeon General report on mental health (DHHS, 2001) brought much needed attention to the role of cultural factors in mental health disparities. In the supplemental report and in the research literature, African Americans are identified as a population that is vulnerable to mental health disparities and faces unique challenges pertaining to mental health care (Safron et al., 2009; Jackson et al., 2004). In particular, some ethnic minorities are disadvantaged in a number of areas (e.g., access to comprehensive services) that impact their interaction with mental healthcare systems (Breland-Noble, 2012; Corbie-Smith, Thomas, & St. George, 2002; Murry, et al., 2004). Previous research has found that the mental healthcare system provides less care to African Americans than to Caucasian Americans, even when adjusting for mental health status (Cook, McGuire, & Miranda, 2007). Additionally, relative to certain mental illnesses such as major depression, ethnic minorities are more likely to experience higher degrees of functional limitation and chronicity compared to Caucasian Americans (Breslau, Kendler, Su, Gaxiola-Aguilar, & Kessler, 2005; Williams et al., 2007).

With regard to help-seeking, research suggests that African Americans are less likely to seek mental health care than their Caucasian American counterparts (Scholle & Kelleher, 2003). When they do seek mental health care, they are more likely to leave treatment prematurely, and more likely to seek initial treatment in primary care settings as opposed to specialty settings (Holden et al., 2012). These help-seeking trends have been linked to a history of mistrust of medical professionals as well as cultural stigma surrounding mental health issues (Holden & Xanthos, 2009). Mistrust of medical professionals stems from well-documented historical accounts of unethical treatment of ethnic minorities in research and practice (DHHS, 2001). Stigma regarding mental health often fosters fear of the system, resulting in a greater proportion of ethnic minorities who are wary of mental health care compared to Caucasian Americans (DHHS, 2001). Unfortunately, this fear makes it less likely that individuals in this group will seek care early in the psychiatric illness. Allowing mental health problems to go untreated can lead to worsening of the illness concomitant with difficulty in controlling symptoms; which may lead to greater utilization of emergency psychiatric services. The greater utilization by ethnic minorities compared to Caucasian Americans of mental health care within emergency rooms is yet another recognized disparity. This setting may not be ideal for obtaining consistent mental healthcare that is commensurate with established evidence based medicine practices. Thus, many ethnically diverse patients may not get the highest quality of services; especially since high utilization of emergency services may be a marker of poor-quality care (Snowden et al., 2009).

Nevertheless, when many ethnic minorities enter treatment for mental health concerns, they are often exposed to inequalities in care (Alegría et al., 2008). For example, ethnic minorities may be under-diagnosed and under-treated for affective disorders, and over-diagnosed and over-treated for psychotic disorders; and are less likely to receive newer and more comprehensive treatment modalities (Greenberg et. al, 2003). These inequalities have been attributed to a lack of cultural competency and bias in service delivery on the part of mental health and medical professionals (Holden & Xanthos, 2009; Shim et al., 2013). Unfortunately, such disparities concerning mental health services and quality care have resulted in poorer mental health outcomes for African Americans (Holden et al., 2013; Baker & Bell, 1999).

The provision of mental health services within primary healthcare settings can be viewed as a way to attempt to address disparities that ethnic minorities experience relative to mental health assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. Thus, the primary care setting offers an opportunity for patients with comprehensive physical, mental and behavioral health problems to elucidate their concerns.

Role of Mental Healthcare in Primary Healthcare Settings

In 2012, the NIMH Office for Research on Disparities and Global Mental Health (ORDGMH) and Division of Services and Intervention Research (DSIR) convened a meeting to assess the state of the science in preventing and treating medical co-morbidities in people with severe mental illness (SMI) and identify the most critically needed research to reduce premature mortality in this vulnerable group. It was concluded that individuals with SMI die 11 to 32 years prematurely from largely preventable co-morbid medical conditions—e.g., heart disease, diabetes, cancer, pulmonary disease, and stroke—all of which occur more frequently and have earlier onset. Low rates of prevention, detection, and treatment further add to these health disparities (Arzin, 2012), as well as create more severe burdens of functional impairment and increased medical costs (NIMH, 2006). Research centered on improving mental health outcomes in the primary care setting is considered a public health priority (Menke & Flynn, 2009). Not only do a large percentage of individuals receive all or part of their mental health treatment in primary care settings (Cooper-Patrick, 1997; Unutzer, 2006), but racial minorities in particular are more likely to report depressive symptoms to primary care physicians than to mental health specialists (Snowden, 2001). However, many primary care physicians are less likely to diagnose depression in this population (Borowsky et al., 2000); and ethnic minorities are underrepresented in outpatient mental health settings (Snowden, 2001; Cooper et al., 2003). Thus, the primary care setting may be a critical link to aid in identifying and addressing mental health problems and associated issues for ethnically and culturally diverse individuals.

There are many psychosocial issues and considerations for disentangling the bidirectional relationship between physical and mental health (Mezuk et al., 2010), and the primary care setting may be optimal to support the effectiveness of providing mental health care as a way of ameliorating mental health disparities for ethnic minorities. Psychiatric illness is associated with great physical, emotional, functional, and societal burden, and there remains a stigma attached to seeking mental healthcare (Hasin et al., 2005; DHHS, 2001); therefore, many individuals may not seek mental health treatment and suffer subsequent negative consequences, particularly among those of racial, ethnic and cultural minority (Interian, Lewis-Fernandez & Dixon, 2012). It has been established that mental health plays a major role in individuals’ ability to maintain good physical health; and mental illnesses may affect individuals’ ability to participate in health-promoting behaviors (Mauer, 2003). In turn, problems with physical health, such as chronic diseases, can have a serious impact on mental health and decrease an individual’s ability to participate in treatment and recovery (Lando et al., 2006). Individuals with serious physical health problems often have co-morbid mental health problems, and nearly half of those with any mental disorder meet the criteria for two or more disorders, with severity strongly linked to co-morbidity (Kessler et al., 2005). As indicated by Robinson and Reiter (2007), as many as 70 percent of primary care visits stem from psychosocial issues. While patients typically present with a physical health complaint, data suggest that underlying behavioral health issues are often triggering these visits. Further, primary care physicians may not be adequately equipped to optimally treat mental health disturbances; and constraints on time often lead to mental health conditions remaining undetected (Unutzer et al., 2006).

Research has improved our ability to recognize, diagnose, and treat mental conditions effectively. In fact, many studies over the past twenty-five years have found correlations between physical and mental health-related problems (Shim et al., 2013). As we are beginning to see the implications of mental illnesses that go untreated, and we are identifying the biological underpinnings of psychiatric illness Engaging patients in treatment, especially racial and ethnic minorities, continues to be a challenge (Interian, Lewis-Fernandez & Dixon, 2012). In order to provide optimal care for the psychiatric patient, modes of treatment need to be individualized and optimized. When mental health disorders are not fully treated, physical health worsens.

There is a movement towards multi-disciplinary comprehensive care that aims to provide mental healthcare in collaboration with the patient’s primary care team. This integration of services provides a bridging of the gap between primary and mental health care. In doing so, mental healthcare providers work closely with the primary care team, and may often work within the same clinic. The benefits to the patient are significant; for example, the rate of follow up increases, as does the compliance with treatment plans. It has been shown that the collaborative care model has stimulated improvement in mental, emotional, and behavioral symptoms more so than usual care that may be provided to patients (Bauer et al., 2011).

The primary care clinic is a busy setting with constraints on “face time” with patients. There is concern about how to assess for depression while treating physical illnesses. Studies of depression screening in primary care practices, conducted by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), found that screening improves the accurate identification of depressed patients in primary care settings, and that treatment of depressed adults identified in primary care settings decreases clinical morbidity. However, although screening may occur, it often is not effectively linked to appropriate follow-up assessment, treatment, and monitoring services (DHHS, 2012).

Screening for mental health problems is important in primary care settings. Thus, screening instruments have become a useful tool for assessing patient’s risk for a myriad of mental illnesses; yet some of these tools are often time consuming, making it unrealistic to deliver these tools in the primary care setting. However, there are self-report screening tools used in primary care settings, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001) which are brief and can be utilized in the busy primary care setting to assess for depressive symptoms and determine response to treatment. The PHQ-9 has adequate psychometric properties, as suggested by several investigations (Manea et al., 2012; Titov et al., 2011; Cameron et al., 2008; Gilbody et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2007; Adewuya et al., 2006). The PHQ-9 is a powerful tool for assisting primary care clinicians in assessing depressive symptoms. The brevity and ease of use of the PHQ-9 makes it a valuable resource; especially in busy practices. The PHQ-9 can be used as an adjunct for diagnostic and severity assessment. Although a tool in the diagnostic assessment, it does not replace the interview and exam. A score of >10 may be an indicator for a referral to the behavioral health component of the primary care center. Another useful mental health assessment instrument in the primary care setting is the BATHE (Lieberman & Stuart, 1999) interviewing tool. The BATHE technique is a psychotherapeutic procedure and serves as a rough screening test for anxiety, depression, and situational stress disorders. The BATHE technique consists of 4 specific questions about the patient’s background, affect, troubles, and handling of the current situation, followed by an empathic response; the procedure takes approximately 1 minute and must be practiced. Physicians may use the BATHE technique to connect meaningfully with patients, screen for mental health problems, and empower patients to handle many aspects of their life in a more constructive way. It is a five-step, brief structured interview technique for gathering information. [Table 1]

Table 1.

The BATHE Technique as a Method for Teaching Patient-Centered Medical Interviewing

| B= Background | “What is going on in your life?” “Tell me what has been happening since I saw you last.” |

| A = Affect | “How do you feel about what is going on?” |

| T = Trouble | “What troubles you about this?” |

| H = Handling | “How are you handling that?” |

| E = Empathy | “Sounds like things are difficult for you.” “Let’s schedule you to see one of our behavioral staff.” |

Overall, these screening tools are brief (not requiring a great deal of time to complete), have adequate psychometric properties, and prove to be useful to clinicians. Thus, we encourage more widespread use of them in primary healthcare settings, where such issues are significant. Patients that screen positive will need further evaluation and appropriate treatment concerning mental health issues. Unfortunately, oftentimes, the treatment that is received in the primary care setting is not optimal. Time constraints can limit the ability to follow a patient’s progress and make appropriate adjustments in treatment. In addition, the primary care provider may lack the specialized training required to effectively manage psychiatric medications (Unutzer, 2006). Frequently, psychotherapy is not offered. However, on-site mental healthcare can reconcile these deficiencies.

Offering on-site mental healthcare is conducive to a patient seeking and remaining compliant with proposed treatment plans (Coleman, Austin, Brach, & Wagner, 2009). Offering these services in a familiar and comfortable environment lessens the stigma that still surrounds the issue of mental health. The enmeshment of behavioral health and primary care makes collaboration between professionals less time consuming. For example, potential side effects from medication can be more easily monitored in the primary setting. The integration of mental and physical health care services can also facilitate improved differential diagnoses of health conditions. For instance, a mental illness symptom may actually mask as a physical disorder/illness. The interface between both primary and mental/behavioral healthcare practitioners is important and can lead to better physical and mental health outcomes, including compliance with treatment and reduction of symptoms.

Improving the screening, treatment and medical care of individuals with serious mental health problems and substance use is a growing area of practice and study (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). Integrating mental health services into a primary care setting offers a comprehensive and efficient way of ensuring that people have access to needed mental health services. Additionally, mental health care delivered in an integrated setting can help to minimize stigma and discrimination, while increasing opportunities to improve overall health outcomes. Successful integration requires the support of a strengthened primary care delivery system/infrastructure as well as a long-term commitment from policymakers at the federal, state, and local levels.

Towards Culturally Centered Integrated Care

According to former United States Surgeon General, David Satcher, MD, PhD FAAFP, FACPM, FACP, culture counts in healthcare settings (Satcher & Pamies, 2005; Misra-Hebert, 2003). Culture is defined by the California Endowment as: “an integrated pattern of learned core values, beliefs, norms, behaviors and customs that are shared and transmitted by a specific group of people.” While there is limited evidence on the impact of culturally sensitive health care models, culturally responsive comprehensive diagnostic and treatment modalities have yielded positive outcomes in reducing depressive symptoms among ethnically and culturally diverse communities (Warren, 1994; Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2007). There is a need to establish comprehensive methods on how to deliver quality and effective mental health services within the context of demonstrating respect for the cultural orientation of the patient. Examples of coordinated care service delivery models, which include behavioral health and primary care, indicate important benefits to pursuing integration and collaboration (Collins et al., 2010). An important next step is to systematically investigate the critical features or mechanisms within these models in order to better understand how they achieve improved outcomes. What is missing from many of the comprehensive models is a cultural underpinning that may yield better engagement of patients, their adherence to proscribed treatments, and improvement of their general well-being and quality of life.

Health care professionals must be able to provide effective care for increasingly diverse communities; and the cultural diversity of the health workforce must reflect diversity in society. Lack of diversity and cross-cultural skills in professional practice may contribute to continued growth in health disparities in the US. For example, as previously indicated, ethnic minorities are less likely to engage in health promotion and disease prevention activities (Wilcox et al., 2003). Therefore, central to the focus of a culturally centered model of comprehensive health care for ethnic minorities should include aims of promoting health equity and reducing health disparities (Tucker et al., 2011; Rust et al., 2006). Implementing health care models that appreciate and respect the wide array of cultural backgrounds is an important strategy in addressing these disparities.

Culturally centered integrated care models must be patient centered, value cultural humility among providers, and be implemented in physical environments that respect and appreciate patient diversity and represented cultures (Tucker et al., 2011). These factors may facilitate a greater degree of trust among patients, health care providers, and clinic staff. Culturally centered health care also conceptualizes the patient-provider relationship as a partnership that emerges from patient centeredness and it is empowerment oriented (Tucker et al., 2007). Health care providers can be responsive to such views of patients through engaging in behaviors and attitudes and fostering clinic characteristics and policies identified as important by culturally diverse patients. Ultimately, successful integration of culturally responsive primary care and behavioral healthcare requires the full support of committed primary care and behavioral health delivery systems.

A culturally congruent model of health recognizes core values and ways of being. For example, spirituality and religious practice as well as the role of the extended family are important sources of emotional, social and material support for ethnic minorities in health care settings (Belgrave & Allison, 2010); and should be incorporated in comprehensive health care models developed for this population. The cultures of racial and ethnic minorities influence many aspects of mental illness, including how patients from a given culture communicate and manifest their symptoms, their styles of coping and their willingness to seek treatment (DHHS, 2001). We recognize the importance of cultural sensitivity as a central component of an effective integrated model of care that has the capacity of achieving improvements in physical health and behavioral health outcomes for ethnic minorities.

There are different models with the goal of integrated health care. [Table 2]. These models are among the most popular. Clinical settings that have become integrated include many of the components advanced by these models which have been the focus in much of the research literature, including investigations establishing their effectiveness with various ethnically and culturally diverse populations (Collins, et al., 2010; Mauer, 2003; Perrin et al, 1989). For example, IMPACT is an evidence based depression care model that has demonstrated effectiveness among older African Americans (Arean et al., 2005). Also, the Patient-Centered Medical Home Model’s emphasizes the importance of understanding and respecting the patient’s values and cultural background. Ethnic minorities are likely to identify with and appreciate the goals, objectives and values central to these integrated care approaches.

Table 2.

Integrated Care Models

| Integrated Care Models | Overview/Description |

|---|---|

| Four Quadrant Model | Population-based planning framework for the clinical integration of health and behavioral health services; describes the need for a bi-directional approach, addressing the need for primary care services in behavioral health settings, as well as the need for behavioral health services in primary care settings. |

| IMPACT | Collaborative care in which the individual’s primary care physician works with a care manager/behavioral health consultant to develop and implement a treatment plan. |

| Chronic Care Model (CCM) | Influenced the development of the patient-centered medical home and is foundational to the Health Disparities Collaborative. |

| Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) | Stress that care under the medical home model must be accessible, family-centered, continuous, comprehensive, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective. |

| Cherokee Health Systems | A real-life integrated setting which articulates the importance of innovation in advancing the integration of primary care and mental health. |

We offer a conceptual framework for consideration of integrated care among African Americans, which may have applicability for other ethnic minorities. The proposed culturally centered integrated care model which may be used by psychologists, psychiatrists, and family medicine providers in a primary care setting to help promote better mental health among African Americans. This model was developed by synthesizing selected components of two models listed in Table 2 that, together, include components of a culturally centered integrated care model that could be rigorously tested through intervention. The two components are the CRASH model, which is an acronym for the essential components of culturally competent health care (Rust et al., 2006) and the Patient Centered Medical Home Model (Stange et al., 2010), both of which are described below. Collectively, these complementary ideologies provide a foundation for a promising culturally centered integrated care model. Others have observed the potential opportunities and benefits within integrated care settings to utilize cultural sensitivity to improve quality and achieve health equity among underserved racial and ethnic minorities (Ell et al., 2009; Betancourt, 2006).

Patient Centered Medical Home Model

The Patient-Centered Medical Home Model (PCMH) has promise for many ethnically and culturally diverse groups and is guided by seven principles which include enhanced access, whole person orientation, coordination of care personal physician, safety and quality physician directed practice team and payment system (Stange et al., 2010) [Table 3]. The PCMH represents collaboration between mental health and primary care, and the future of integrated health care (Stange et al., 2010). The patient and/or family are the focal point and center around which the medical home is built. Patient centeredness facilitates a culturally sensitive approach to health care delivery. For example, adopting strategies that promote access to care such as “open scheduling” which allows for blocks of time during clinic sessions that patients have the option to “walk in” without a scheduled appointment time, and receive care may be advantageous. Additionally, enhancing communication with patients, particularly offering time to learn about familial, socio-cultural, and/or environmental issues that may be important in their lives may improve overall provider rapport. This may be particularly significant for African American patients that value principles such of harmony, balance, interconnectedness, cultural awareness, and authenticity (Phillips, 1990). Alternative methods for flexible payment structures, particularly in a fee-for-service health care system, may prove to be beneficial to support economic disadvantages that may exist for some African American patients from underserved communities. For example, Robinson (2001) suggests that “payment innovations that blend elements of fee-for-service, capitation, and case rates can preserve the advantages and attenuate the disadvantages of each. These innovations include capitation with fee-for-service carve-outs, department budgets with individual fee-for-service or “contact” capitation, and case rates for defined episodes of illness. The context within which payment incentives are embedded, includes such non-price mechanisms as screening and monitoring and such organizational relationships as employment and ownership. The analysis has implications for health services research and public policy with respect to physician payment incentives.”

Table 3.

Joint Principles of the Patient Centered Medical Home

| Principle | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Personal Physician | Each patient has an ongoing relationship with a personal physician rained to provide first contact, and continuous and comprehensive care. |

| 2 | Physician Directed Medical Practice | The personal physician leads a team of individuals who collectively take responsibility for the ongoing care of each patient. |

| 3 | Whole Person Orientation | Personal physician is responsible for providing the entire patient’s health care needs or taking responsibility for appropriately arranging care with other qualified professionals – includes care for all stages of illness and all stages of life. |

| 4 | Care is coordinated and/or integrated | Across all elements of the complex health care system … and facilitated to assure that patients get the care when and where they need and want in a culturally and linguistically appropriate manner. |

| 5 | Quality and Safety | Ensured through specific practices of accountability outlined under the Joint Principles. |

| 6 | Enhanced Access to Care | Through systems; i.e., open scheduling, expanded hours, and new options for communication between patients, their personal physician, and practice staff. |

| 7 | Payment | Structure should be based on a framework that recognizes and reflects the value of physician and non-physician staff patient- centered care management work that falls outside of the face-to- face visit with the physician. |

Another key feature of the PCMH is that, implementing it within a practice setting requires not only individual level change but a change in practice culture. This paradigm shift covers mental and physical domains such that the entire practice is transformed to embrace and adopt shared perspectives, expectations and beliefs reflective of the seven principles (Cronholm et al., 2013). We argue that because of the philosophical and theoretical similarities underpinning the PCMH and primary care and behavioral health integration and because PCMH practices target many of the challenges faced by African American and other ethnic minority patients in a variety of other settings, it provides a practice infrastructure that is central to our proposed culturally centered integrated care model.

CRASH: A Course in Cultural Competency Training

Developed at Morehouse School of Medicine, the CRASH Course in Cultural Competency training program has been developed to help medical professionals care for an increasingly diverse patient population while minimizing culturally dysfunctional behaviors and providing a specific and measurable skill sets in accruing a sense of cultural competence (Rust et al., 2006). CRASH is a mnemonic for: Considering Culture, showing Respect, Assessing/Affirming differences, showing Sensitivity/Self-Awareness, and to do it all with Humility. The goal of the CRASH Course in Cultural Competency is to build confidence and competence in the clinician’s ability to communicate effectively with diverse patient populations. Culture is related to health promotion, disease prevention, early detection, access to health care, trust, and compliance (Rust et al., 2006). CRASH has been developed into a course aimed at providing medical professionals with a system for addressing and acknowledging cultural differences. CRASH provides health care professionals principles to inform strategies to incorporate patient’s culture into medical decision making.

The primary aim of the CRASH course is to develop cultural competency, and the first step includes acknowledgement of the importance of culture for our patient populations. Knowledge of culture leads to the second component of the CRASH model-respect. Respect in the CRASH model implies that individuals have the right to receive respect according to their own personal perspective (Rust et al., 2006). Simple interventions, like asking the patient what will help them feel respected, is conducive to better professional-patient interaction. In turn, respect fosters trust. Assessing patient’s cultural history is often important and should be done for each patient, taking care not to make assumptions about individuals based on group membership. Medical professionals must understand that there is heterogeneity within group. For example, individuals from places such as Colombia and Spain will be lumped into the broad category of Hispanic. Hispanic refers to Spanish speaking people in the Americas; and Latino refers to people from the Caribbean (e.g. Puerto Rico, Cuba, Dominican Republic), South America (e.g. Ecuador, Bolivia, Colombia, Peru, etc.) and Central America (e.g. Honduras, Costa Rica, etc.) who may speak a language derived from Latin. Taking an interest to ask simple questions such as “Tell me about your family background,” can help practitioners learn more about the patient (Rust et al., 2006). Subsequently, their cultural experience is affirmed.

Sensitivity and self-awareness, components of the CRASH model, asks medical professionals to be keen to specific perceptions within cultures. Being culturally sensitive and aware keeps medical professionals from breaking trust with the patient. Understanding our own cultural views and biases is important to be fully self-aware.

The last step of the CRASH model is to develop humility. It is difficult for any individual to be completely culturally competent. Instead, this step asks the medical professional to commit to learning from his or her patients and to make this a life -long commitment. Offering an apology for a cultural misstep offers the patient solace while providing a learning opportunity for the medical professional. Medical professionals are in a unique role since they often encounter patients when they are at their most vulnerable. We believe that it is important for us to realize this and to provide comfort. A component to this is to offer acknowledgment of their cultural story which strengthens the therapeutic bond. [Figure 1]

Figure 1.

Primary Components of the CRASH Course in Cultural Competency Skills. This figure describes each of the primary components of the CRASH Course.

Proposed Culturally Centered Integrated Care Model

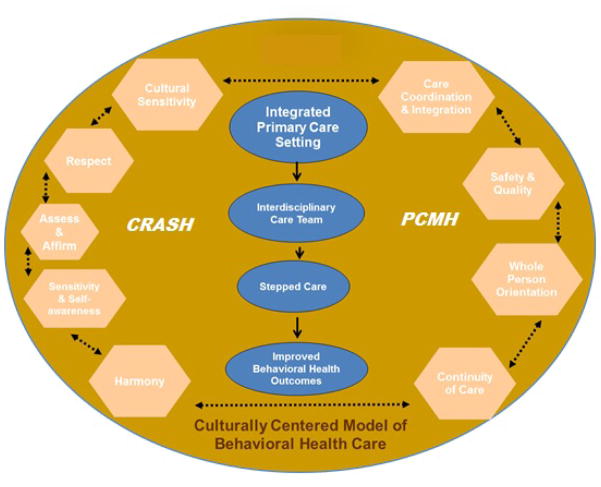

Taken together, the principles of CRASH model and the PCMH address the complex and multiple levels within the health care system--from the individual level, that includes provider and patient factors, to the system level, which include practice culture and system functionality issues. The rational for combining elements of these two conceptual models is that they complement each other in a way that promotes cultural sensitivity and facilitates the implementation of a health care delivery system that has the potential to remove many of the barriers that ethnically and culturally diverse populations experience in other health care settings. Together, components of PCMH and CRASH offer strategies for demonstrating reverence for patients and contextualization of their background experiences, socio-cultural, and environmental issues that may have relevance for their health behaviors. For example, the Commonwealth Fund observed that while patient registries are essential in integrated settings, a culturally competent approach to these registries would allow identification by race, language and other demographics to facilitate identification of groups that may be at risk for negative outcomes, including dropping out (Betancourt, 2006). This identification is an example of assessing and affirming differences, a CRASH principle. Health care practitioners that are knowledgeable of CRASH and embrace its principles will recognize these kinds of opportunities to more aptly address the needs of a diverse patient population. Additionally, it is important that a focus on the significance of linguistic differences and/or barriers that may be present between patient and provider(s) be fully explored in order to offer optimal care (Purnell, 2013; Flores, 2006; Anderson et al., 2003; Flores et al, 2000). [Figure 2]

Figure 2.

Culturally Centered Model of Behavioral Health Care. This figure contains a description of the proposed model of behavioral health care.

Model description: the oval represents the environmental context within which all of the protocol, procedures, and principles are exercised and there must be alignment between each aspect of integrated care. Dotted lines that go between each box on the outer edges of the circle on the left and the right reflect the connectedness that must exist between the underlying core set of skills needed to effectively engage ethnically diverse populations and the central features of the medical care home. The CRASH principles are on the left and four of the seven joint principles of the PCMH model are on the right. There must be congruence between each of these principles and practice features to create an environment where the patient feels comfortable engaging each member of their interdisciplinary care team. This increases the likelihood that patients will adhere to treatment recommendations which improves patient flow and maximizes the efficiency of the practice in its ability to care for the mind, body and spirit of the community they serve. Principles of CRASH model will help to guide training in cultural sensitivity for practitioners. We propose that if each of the features in the conceptual model is fully realized, ultimately there will be improvements in aspects of care such as screening, referrals, diagnosis and treatment. Nevertheless, it is clear that practitioners must utilize approaches that are feasible, realistic, and practical in a primary care setting. We propose the following: 1) include self-report/service kiosks that screen for mental health problems and query background information, 2) include an onsite mental health practitioner to assess patients and provide care, 3) include comprehensive mental health educational resources that are culturally tailored for diverse patient populations, and 4) offer extended hours of operation and on-site mental health support services to patients. These approaches may encourage more self-efficacy among patients and an affiliation of the primary care center as a comfortable place to share mental, emotional, and/or behavioral health concerns. This may in turn help to 1) reduce stigma associated with mental health problems, 2) encourage patients to participate in mental health screenings, assessments, and treatment, and 3) reduce mental health disparities.

Implications for Professional Clinical Practice

After diabetes and hypertension, mental illness is the third most common reason for seeking treatment at a health care facility. The rates of mental health problems are significantly higher for patients with certain chronic conditions, such as diabetes, asthma, and heart conditions (DHHS, 2012). As indicated in the World Health Organization (WHO) report, Integrating Mental Health into Primary Health Care: A Global Perspective (2008), “more than 50 percent of patients currently being treated receive some form of mental health services treatment from a primary care provider; and primary care is now the sole form of health care used by over 30 percent of patients with a mental disorder accessing the health care system” (WHO, 2008). Therefore, it is vital that mental health services are integrated with primary care services.

Recognizing a patient’s needs is one of the most important steps to providing care. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-9) or BATHE can be routinely administered during triage. Routine screening will make the primary care physician aware of possible symptoms indicative of a mental health condition, which will, in turn, guide treatment. A positive screen can be the catalyst for on-site consultations with a mental health specialist, who can first determine the patient’s needs and then connect the patient with the appropriate follow up. Having mental health services available in the familiar environment of the primary care clinic often reduces stigma; therefore, compliance rates improve leading to better outcomes.

The CRASH model and PCMH model can guide professionals in an integrated health care setting to provide culturally competent health care. For example, understanding how a patient interprets and expresses his/her depression will guide diagnosis and treatment. It is well known that African Americans often have somatic symptoms as part of their depression (Shim et al. 2013). However, without careful and culturally based assessment, those somatic symptoms may be seen as somatic delusions by the health care professional; thereby, the patient is susceptible to getting a psychotic illness diagnosis rather than the correct diagnosis of depression. This, in turn, may lead to inappropriate treatment for the individual, leading to ineffective treatment for depression, and eventual termination of treatment by the patient, leading to poor outcomes. A health care team that considers culture, shows respect and assesses and affirms patient differences, three principles within the CRASH model, will provide patients a comfortable, supportive environment to express their mental health concerns and thus a careful and culturally based assessment. Further, the PCMH model’s emphasis on utilizing a whole person orientation facilitates provider-patient interactions that create opportunities for a thorough and culturally sensitive assessment. Utilizing principles from these two models create a symbiotic relationship within the health care team, with the patient at the center, and an environment that enhances access, quality and safety. The integration of services also contributes to a reduction in patients’ reluctance to pursue mental health and behavioral health services, in addition to reduced language and cultural barriers. As concluded in the IOM report, Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series (2005), “the only way to address disparities in the health care system is to integrate primary care with mental health care.” Using the proposed Culturally Centered Model of Behavioral Health Care, specific recommendations for mental health practitioners working in primary care settings with ethnically and culturally diverse clients/patients include: (1) establish a strong collaborative partnership with primary care physicians and clinic case managers for enhanced bi-directional communication and information exchange about client/patient health and mental health issues. This will improve care coordination and the likelihood of identifying risk and protective factors that may contribute to treatment planning, adherence and improved outcomes; (2) assess cultural biases, stereotypes, and ethnocentric views that may impact establishing rapport with clients/patients seeking care. This will help further sensitize practitioners to psychosocial, socio-cultural, and environmental issues that may contribute to symptom severity and related concerns, as well as promote a non-judgmental position; (3) use culturally sensitive methods for screening, assessment, and treatment for clients/patients. This will include recognition of aspects of culturally derived practices and norms of clients/patients of African descent; and 4) acknowledge the role of faith based initiatives that may be helpful to encouraging greater access and utilization of health services.

Although cultural competence is rarely fully actualized, it is helpful to consistently aspire towards increased learning and understanding about cultural differences among various ethnic groups. Overall, recognition of the value in promoting culturally centered integrated care, and implementation of strategies will help contribute to the reduction of mental health disparities and promote better health, mental health and well-being for ethnic minority individuals, families, and communities. Additional research is necessary to test the proposed model with diverse ethnic minorities.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments of Support:

This project was supported by NIH Grants 5U54RR026137, KL2-RR025009 2R25RR017694-06A1, and U54MD008173.

Contributor Information

Kisha Holden, Psychologist and Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Deputy Director, Satcher Health Leadership Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Brian McGregor, Psychologist and Instructor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Behavioral Health Researcher, Division of Health Policy, Satcher Health Leadership Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Poonam Thandi, Psychiatric Resident, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Edith Fresh, Psychologist and Associate Professor, Department of Family Medicine; Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Director of Behavioral Health, Comprehensive Family Healthcare Center, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Kameron Sheats, Psychologist and Health Policy Fellow, Satcher Health Leadership Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Allyson Belton, Research Assistant, Satcher Health Leadership Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

Gail Mattox, Psychiatrist, Chairperson and Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

David Satcher, 16th US Surgeon General, Director, Satcher Health Leadership Institute, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA.

References

- Adewuya A, Ola B, Afolabi O. Validity of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression amongst Nigerian university students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;96 (1–2):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agency Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) National Health Disparities Report. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr12/2012nhdr.pdf.

- Alegría M, Chatterji P, Wells K, Cao Z, Chen CN, Takeuchi D, Meng XL. Disparity in depression treatment among racial and ethnic minority populations in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(11):1264–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L, Scrimshaw S, Fullilove M. Culturally competent healthcare systems: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;24 (3):68–79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arean PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, Lin EH, Tang L, Harpole L, Hendrie H, Williams JW, Unutzer S. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Medical Care. 2005;43(4):381–390. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arzin S. Research to Improve Health and Longevity of People with Severe Mental Illness. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/scientific-meetings/2012/research-to-improve-health-and-longevity-of-people-with-severe-mental-illness.shtml.

- Baker PM, Bell C. Issues in psychiatric treatment of African Americans. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:362–368. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Azzone V, Goldman HH, Alexander L, Unutzer J, Coleman-Beattie B, Frank RG. Implementation of Collaborative Depression Management at Community-Based Primary Care Clinics: An Evaluation. Psychiatric Services. 2011;62(9):1047–1053. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.9.1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauboeuf-Lafontant T. You have to show strength: An exploration of gender, race, and depression. Gender & Society. 2007;21(1):28–51. [Google Scholar]

- Belgrave FZ, Allison KW. African American Psychology: From Africa to America. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(6):3881–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland-Noble AM, Bell CC, Burriss A, Poole HK. The significance of strategic community engagement in recruiting African American youth & families for clinical research. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2012;21(2):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10826-011-9472-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, Gaxiola-Aguilar S, Kessler RC. Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine. 2005;35(3):317–327. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704003514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron I, Crawford J, Lawton K, Reid I. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. British J Journal of General Practice. 2008;58 (546):32–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X263794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) 2011;60(Suppl):1–32. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/other/su6003.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the Chronic Care Model in the new millennium. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C, Hewson DL, Munger R, Wade T. Evolving models of behavioral health integration in primary care. Millbank Memorial Fund 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, McGuire T, Miranda J. Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000–2004. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(12):1533–1540. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, Rost KM, Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Ford DE. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care. 2003;41(4):479–489. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000053228.58042.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1997;12(7):431–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, StGeorge DM. Distrust, race, and research. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(21):24–58. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman DS. Blending behavioral health into primary care at Cherokee Health Systems. The Register Report. 2007:32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Flores G. Language barriers to health care in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:229–231. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores G, Abreu M, Schwartz I, Hill M. The importance of language and culture in pediatric care: Case studies from the Latino community. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;137 (6):842–848. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Richards D, Brealey S, Hewitt C. Screening for depression in medical settings with the Patient Health Questionnaire: A diagnostic meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22(11):1596–1602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0333-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales JJ, Papadopoulos AS. Mental Health Disparities. In: Levin BL, Hennessy KD, Petrila J, editors. Mental health services: a public health perspective. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg GA, Rosenbeck RA. Changes in mental health service delivery among blacks, whites and Hispanics in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Administrative Policy and Mental Health. 2003;31:31–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1026096123010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden KB, Xanthos C. Disadvantages in mental health care among African Americans. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2009;20(2A):17–23. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden K, Hall S, Robinson M, et al. Psychosocial and socio-cultural correlates of depressive symptoms among diverse African American Women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2012;104 (11–12):493–503. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden KB, McGregor BS, Blanks SH, Mahaffey C. Psychosocial, socio-cultural, and environmental influences on mental health help-seeking among African-American men. Journal of Men’s Health. 2012;9(2):63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jomh.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden K, Bradford D, Hall S, Belton A. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms and resiliency among African American women in a community based primary healthcare center. Journal of Healthcare for the Poor and Underserved. 2013 doi: 10.1353/hpu.2014.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt TR, Beach SR, Stokes LA, Bush PL, Sheats KJ, Robinson SG. Engaging African American men in empirically based marriage enrichment programs: Lessons from two focus groups on the ProSAAM project. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18(3):312. doi: 10.1037/a0028697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Improving the quality of health care for mental and substance-use conditions: quality chasm series. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Lewis-Fernandez R, Dixon L. Improving treatment engagement of underserved U.S. racial-ethnic groups: A review of recent interventions. Psychiatric Service. 2013;64(3):212–222. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Neese RM, Taylor RJ, Williams DR. The National Survey of American Life: a study of racial, ethnic, and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman JA, Stuart MR. The BATHE Method: Incorporating counseling and psychotherapy into the everyday management of patients. Primary Care Companion to the Journal Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;1(2):35–38. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v01n0202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lando J, Williams MS, Sturgis S, Williams B. A logic model for the integration of mental health into chronic disease prevention and health promotion. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2006;3(2):A61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Schulberg H, Raue P, Kroenke K. Concordance between the PHQ-9 and the HSCL-20 in depressed primary care patients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99 (1–3):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2012;184(3):191–196. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauer BJ. Background paper: behavioral health/primary care integration models, competencies, and infrastructure. Rockville, Maryland: National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare (NCCBH); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Menke R, Flynn H. Relationships between stigma, depression, and treatment in White and African American primary care patients. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2009;197(6):407–411. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a6162e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezuk B, Rafferty JA, Kershaw KN, Hudson D, Abdou CM, Lee H, Eaton WW, Jackson JS. Reconsidering the Role of Social Disadvantage in Physical and Mental Health: Stressful Life Events, Health Behaviors, Race, and Depression. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;172(11):1238–1249. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra-Hebert AD. Physician cultural competence: cross-cultural communication improves care. Cleveland Clinical Journal of Medicine. 2003;70(4):289–296. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.70.4.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Kotchick BA, Wallace S, Ketchen B, Eddings K, Heller L, Collier I. Race, culture, and ethnicity: Implications for a community intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13(1):81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Perceived need for care among low-income immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women with depression. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18(3):369–375. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Benefits to Employers Outweigh Enhanced Depression-Care Costs. 2006 Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/science-news/2006/benefits-to-employers-outweigh-enhanced-depression-care-costs.shtml.

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Health Disparities Strategic Plan. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about_ncmhd/index2.asp.

- Passel J, Cohn D. Trends in unauthorized immigration: undocumented inflow now trails legal inflow. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/10/02/trends-in-unauthorized-immigration/

- Patient Centered Primary Care Collaborative. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. 2007 Retrieved from http://www.pcpcc.net/content/joint-principles-patient-centered-medical-home.

- Perrin JM, Homer CJ, Berwick DM, Woolf AD, Freeman JL, Wennberg JE. Variations in rates of hospitalization of children in three urban communities. New England Journal of Medicine. 1989;320(18):1183–1187. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198905043201805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips FB. NTU Psychotherapy: An Afrocentric approach. Journal of Black Psychology. 1990;17(1):55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Purnell L. Trans-cultural Health Care: A Culturally Competent Approach. FA Davis Company; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. Theory and practice in the design of physician payment incentives. Milbank Quarterly: A Multidisciplinary Journal of Population Health and Health Policy. 2001;79 (2):149–177. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust G, Kondwani K, Martinez R, Dansie R, Wong W, Fry-Johnson Y, Strothers H. A CRASH-Course in cultural competence. Ethnicity & Disease. 2006;16:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran MA, Mays RA, Huang LN, McCuan R, Pham PK, Fishter SK, Trachtenberg A. Mental health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(11):1962–1966. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satcher D, Pamies RJ. Multicultural Medicine and Health Disparities. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Scholle SH, Kelleher K. Preferences for depression advice among low- income women. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2003;7(2):95–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1023864810207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim R, Bradford Baltrus PT, Bradford D, Holden K, Fresh E, Fuller LE. Characterizing depression and co-morbid medical conditions in African American women in a primary care setting. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2013 doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30106-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR. Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. Mental Health Services Research. 2001;3(4):181–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1013172913880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR, Catalano R, Shumway M. Disproportionate use of psychiatric emergency services by African Americans. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(12):1664–1671. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaén CR, Crabtree BF, Flocke SA, Gill JM. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(6):601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart MR, Lieberman JA., III . The fifteen minute hour: Applied psychotherapy for the primary care physician. Westport: Connecticut: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Mental Health Findings. Rockville, Maryland: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Titov N, Dear B, McMillan D, Anderson T, Zou J, Sunderland M. Psychometric Comparison of the PHQ-9 and BDI-II for Measuring Response during Treatment of Depression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2011;40 (2):126–136. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.550059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treadwell H, Xanthos C, Holden K. Social Determinants of Health Among African-American Men. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker CM, Herman KC, Ferdinand LA, Bailey TR, Lopez MT, Beato C, Cooper LL. Providing patient-centered culturally sensitive health care: a formative model. The Counseling Psychologist. 2007;35(5):679–705. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker CM, Marsiske M, Rice KG, Jones JD, Herman KC. Patient-centered culturally sensitive health care: model testing and refinement. Health Psychology. 2011;30(3):342–350. doi: 10.1037/a0022967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unutzer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss B, Katon W. Transforming Mental Health Care at the Interface with General Medicine: Report for the Presidents Commission. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(1):37–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Mental Health: Strategic Plan. NIMH Publication No. 08-6368. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/strategic-planning-reports/index.shtml.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Affordable Care Act. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/opa/affordable-care-act/index.html.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health and Mental Disorders. Healthy People 2020. 2012 Retrieved from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=28.

- Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(S1):S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward EC, Clark LO, Heidrich S. African American women’s beliefs, coping behaviors, and barriers to seeking mental health services. Qualitative Health Research. 2009;19(11):1589–1601. doi: 10.1177/1049732309350686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren BJ. Depression in African American women. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing Mental Health Services. 1994;32(3):29–33. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-19940301-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Bopp M, Oberrecht L, Kammermann SK, McElmurray CT. Psychosocial and perceived environmental correlates of physical activity in rural and older African American and white women. The Journals of Gerontology. 2003;58(6):329–337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.p329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, Jackson JS. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the national survey of American life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008-Primary care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008b. [Google Scholar]

- World Organization of National Colleges, Academies, and Academic Associations of General Practitioners/Family Physicians. Integrating mental health into primary health care: a global perspective. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]