Abstract

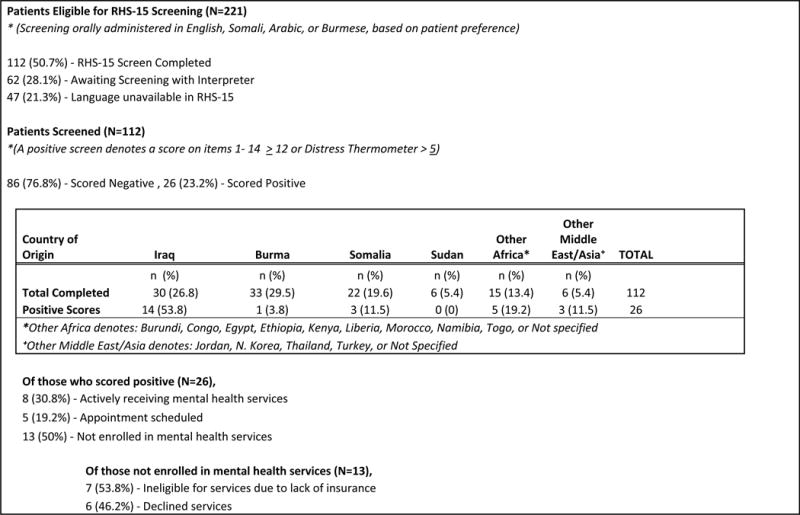

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression are the most common mental health disorders in the refugee population. High rates of violence, trauma, and PTSD among refugee women remain unaddressed. The process of implementing a mental health screening tool among multi-ethnic, newly-arrived refugee women receiving routine obstetric and gynecologic care in a dedicated refugee women’s health clinic is described. The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) is a culturally-responsive, efficient, validated screening instrument that detects symptoms of emotional distress across diverse refugee populations and languages. An interdisciplinary community partnership was established with a local behavioral health services agency to facilitate the referral of women scoring positive on the RHS-15. Staff and provider training sessions, as well as the incorporation of bi-cultural, multi-lingual Cultural Health Navigators, greatly facilitated linguistically-appropriate care coordination for refugee women in a culturally sensitive manner. Twenty-six (23.2%) of the 112 women who completed the RHS-15 scored positive; of which 14 (53.8%) were Iraqi, one (3.8%) was Burmese, and three (11.5%) were Somali. Among these 26 women, eight (30.8%) are actively receiving mental health services, and five (19.2%) have appointments scheduled. However 13 (50%) are not enrolled in mental health care due to either declining services (46.2%), or a lack of insurance (53.8%). Screening for mental disorders among refugee women will promote greater awareness and identify those individuals who would benefit from further mental health evaluation and treatment. Sustainable interdisciplinary models of care are necessary to promote health education, dispel myths and reduce the stigma of mental health.

Keywords: Refugee Health Screener (RHS-15), refugee women, women’s health, community-based participatory research

Introduction

Refugee women and girls constitute 49% of persons of concern to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and account for 48% of all refugees, as well as half of all internally displaced persons and returnees (former refugees) worldwide (UNHCR, 2011a). ‘Women-at-risk’, as defined by the UNHCR Resettlement Handbook, encompasses situations where women’s safety or well-being remains threatened on the basis of gender, ethnicity, religion, culture, and power structure (UNHCR, 2011b; UNHCR, 2013). The percentage of UNHCR resettlement referrals as women-at-risk has risen from 6.8% in 2007 to 11.1% in 2011 (UNHCR, 2013). In 2011, the United States (U.S.) resettled almost half of the UNHCR women-at-risk referrals worldwide, comprising approximately 4% of total U.S. refugee admissions (UNHCR, 2013). Refugee women are often stigmatized or victimized as survivors of rape, abuse, and a wide range of traumatic war-related violence (Hollifield, et al., 2006). Evidence suggests that refugee women resettled in Western countries possess a tenfold risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms than women of the same age in the general population (Kirmayer, et al., 2011).

There are numerous pre- and post-migratory stressors that may impact a refugee woman’s health throughout her process of resettlement (Gagnon, Tuck & Barkun, 2004), and are associated with increased risk for depression, anxiety, and PTSD. The experience of past trauma is only one of many issues facing refugees (Davidson, Murray, & Schweitzer, 2008), as past trauma may also persist in the form of acculturative stress related to loss of family and social networks, family and friends remaining in refugee camps and combat zones, social isolation, social stigma, shifting gender roles, racism, language barriers, loss of employment and socioeconomic status, and intergenerational conflicts (Essen, Hanson, Ostergren, Lindquist, & Gudmundsson, 2000;Fung, & Wong, 2007; Redwood-Campbell, et al., 2008; Siegel, Horan, & Teferra, 2001).

Furthermore, refugees must learn to navigate an entirely new community, language, and cultural system, while simultaneously coping with the loss of homeland, family, and way of life (Murray, Davidson, & Schweitzer, 2010). Evidence suggests that refugee women’s personal experience with biomedicine, fear, and lack of awareness about mental health influences how they seek help to manage mental distress (Donnelly, et al., 2011). Inadequate local services or support networks to respond to this vulnerable population may increase their risk of re-traumatization in their country of first asylum (UNHCR, 2013). An examination of the mental health status of newly arrived Burmese refugees in Brisbane, Australia found that while pre-migration exposure to traumatic events impacted Burmese refugees’ mental well-being, it was their post-migration living difficulties (i.e. communication barriers, worry about family not in Australia, difficulties with employment, and difficulty accessing health and social services), which had greater relevance in predicting mental health outcomes (Schweitzer, et al., 2011). In addition, an examination of the mental health status of Iraqi refugees resettled in the U.S. found that longer duration in the U.S., rating one’s health as fair or poor, and having a self-reported chronic health condition were associated with an increased likelihood of reported depression (Taylor, et al., 2013). Consequently, it is important to increase the awareness of potential mental disorders in the refugee community and connect identified individuals with available resources. Screening for mental disorders among refugee women will promote greater awareness and identify those individuals who would benefit from further mental health evaluation and treatment.

As of January 2011, approximately 264,574 refugees resided in the U.S. (UNHCR, 2011a). In 2012, Arizona ranked eighth nationally in resettling new refugee arrivals to the U.S. (ORR, 2012). The detection of mental disorders remains challenging. There is limited availability of valid and reliable tools for assessing mental health in the refugee population (Gagnon, et al., 2004; Hollifield et al., 2002). As many refugees are not literate in English, valid, reliable, linguistically and culturally appropriate screening instruments for the most common mental disorders (anxiety, depression and PTSD), are critical to accurately assess refugees’ mental health needs and to refer them to appropriate services. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has established guidelines for mental health screening of newly arrived refugees during the domestic medical examination (CDC, 2011). However, each state differs in assistance given, and mental health screening is only sporadically offered (Barnes, 2001).

The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15) was developed by the Pathways to Wellness: Integrating Community Health and Well-being project as a culturally-responsive, efficient, validated screening instrument that detects symptoms of anxiety, depression, and PTSD across multiple refugee populations. It has been validated in the following languages: Arabic, Burmese, and Nepali, while translations are available in: Farsi, Karen, Russian, and Somali; and the process of translation is currently underway for French, Amharic, Tigrinya, and Swahili (Hollifield, et al., 2013; Pathways to Wellness, 2011). The RHS-15 has been field-tested for use in public health and community settings, and requires limited training for staff, and adds approximately five to ten minutes to a patient’s visit. Health care providers who are in close contact with refugee patients have a role in identifying women with potential mental health concerns. Use of the RHS-15 as a behavioral health screen for refugee women will enhance our understanding of their mental health service needs and facilitate referrals for targeted mental health services and interventions. This paper presents preliminary findings of the process of implementation of the RHS-15 and rates of probable mental disorders among newly-arrived refugee women receiving routine obstetric and gynecologic care.

Methods

The Refugee Women’s Health Clinic (RWHC) is a dedicated clinic which cares for newly-arrived refugee women from over 35 countries across Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East; providing comprehensive women’s health services across the reproductive life span with a team of bi-cultural, multi-lingual, Cultural Health Navigators (CHNs), a program manager skilled in social work and case management, and medical assistants; all of whom reflect the ethnic and cultural diversity of the patient population served. Female obstetrician and gynecologists and certified nurse midwives provide clinical services. The RWHC has an established infrastructure of community partnership, engagement, and shared community leadership through its Refugee Women’s Health Community Advisory Coalition (RWHCAC), which represents an interdisciplinary team of greater than 60 individuals from community organizations including local ethnic organizations, refugee resettlement and voluntary agencies, mental health and social services agencies, as well as academic partners who serve as co-equal partners in the community outreach and engagement activities of the RWHC, informing the RWHC’s initiatives, as well as facilitating the coordination of culturally competent care, services, and support.

Community-Partnered Approach and Engagement

Community engagement was an essential step in creating a ‘safe space’ for dialogue on mental health. It was important to glean from the community their perceived need for care and receptivity to accessing mental health services. Hence community outreach and mental health education became a critical component of the implementation of this initiative which enabled the team to understand cultural and logistical challenges in reaching the refugee community. The CHNs were an integral part of this process wherein educational seminars were held with key community members, refugee resettlement agencies, providers, and refugee women to discuss issues of distrust of the health care system, and provide orientation to the historical background and culture of the various refugee communities served.

Behavioral Health Partnership

An interdisciplinary partnership was established with Jewish Family and Children Services (JFCS), a local behavioral health services agency sensitive to the needs of refugee populations. A joint work plan was created to maximize the seamless integration of culturally appropriate evaluation and treatment modalities. Cross-cultural training sessions were held with staff, CHNs, therapists, and clinicians from the RWHC and JFCS, as well as the senior author, representing Pathways to Wellness; to provide orientation to the RHS-15, discuss the logistical process of screening, patient eligibility requirements, and referral processes. In addition, for patients referred for services, mechanisms were in place to ensure that their linguistic and transportation needs were met. This also provided an opportunity for the team to understand the processes that were in place by JFCS to provide mental health evaluation and treatment.

As a result of these sessions, a bi-cultural, multi-lingual peer navigator from the refugee community was hired by JFCS to facilitate the linguistic and care coordination needs of the refugee community in a culturally sensitive manner. Our collaboration was further strengthened by the RWHCAC, which provided a community-wide forum to discuss the newly-formed partnership, dispel myths and stigma concerning mental health, as well as gain critical input and support from the refugee community on how best to ensure a seamless referral and integration process for women who scored positive on the RHS-15. In this setting, as implementation of the RHS-15 was evaluative, a review by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) was obtained.

Implementation of the Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15)

The RWHC partnered with Pathways to Wellness to implement the RHS-15 across its multi-ethnic refugee population. Details of the process of development and validation of the RHS-15 have been published (Hollifield, et al., 2013). The 15-question screener consists of two sections. The first 14 questions are rated on a scale from zero (“not at all”) to four (“extremely”) with variably full jars of sand representing these numbers. A total score equal to or greater than 12 on the first 14 questions is a positive screen. Question 15 comprises the second section which is a distress thermometer where individuals can mark their distress from zero (“no distress”) to 10 (“extreme distress”). A distress thermometer score equal to or greater than five is a positive screen. An individual only has to score positive on one of these two sections to warrant a positive screen (Pathways to Wellness, 2011).

Between April – October 2012, women over the age of 18 receiving routine women’s health care in the RWHC were screened in the preferred language of their choice: Arabic, Burmese, English, Karen, Nepali or Somali; and with the assistance of a CHN. If a patient scored positive on the RHS-15, her health care provider would then discuss the screening results with the patient and assess whether she would be amenable to be referred for a formal mental health evaluation. If the patient agreed to be referred, care coordination would then ensue between the RWHC and the behavioral health service partner agency wherein follow-up appointments were scheduled within one week of screening and included arrangements for appropriate language interpretation services and transportation if necessary; to ensure seamless continuity of care and the seamless integration of health care services.

Results

RHS-15

As displayed in Table 1, 221 women were eligible for screening. Over the course of seven months, trained CHNs verbally administered the RHS-15 in English, Somali, Burmese, or Arabic based on patient language preference and the availability of a CHN. The RHS-15 was completed in 112 (50.7%) of the eligible sample; while 62 (28.1%) were awaiting the availability of an interpreter, and for 47 (21.3%), the RHS-15 was not available in their language. Twenty-six (23.2%) scored positive on the RHS-15, of which 14 (53.8%) were Iraqi; while one (3.8%) was Burmese, and three (11.5%) were Somali. Among these 26 women, eight (30.8%) are actively receiving mental health services, and five (19.2%) have appointments scheduled. However 13 (50%) are not enrolled in any mental health care due to either declining services (46.2%), or a lack of insurance (53.8%).

Table 1.

|

Sustainability

As a result of the first seven months of this initiative, educational seminars and trainings remain ongoing. Efforts are also being made to close gaps in services for the uninsured by partnering with local behavioral health resources to provide psychological counseling and therapy for newly-arrived refugees. The refugee community, health care providers, and social service agencies acknowledge the need for distinct and culturally-responsive mental health services tailored to the refugee population, particularly refugee women. Furthermore, efforts to promote community capacity-building, mutual bi-directional learning, community empowerment, and co-equal partnership are understood to be critical for sustained success in the reduction of mental health disparities in this population.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first reported and targeted program in the U.S. utilizing the RHS-15 among a multi-ethnic sample of newly-arrived refugee women seeking routine obstetric and gynecologic care. This innovative initiative identified women with emotional distress who would otherwise not have been referred for a mental health assessment. Furthermore a unique and robust interdisciplinary partnership was built between an obstetrics and gynecology practice specifically dedicated to caring for newly-arrived refugee women and a behavioral health services agency. A community-partnered approach engendered trust, promoted mutual bi-directional learning, and refugee empowerment towards greater receptivity to mental health services. In addition, refugee community capacity-building in mental health was promoted through the RWHC’s CHNs, as well as the hiring of a patient navigator from the refugee community by JFCS. This initiative was also an opportunity for providers to better comprehend mental health disparities and health equity across a vulnerable medically-complex population. Providers caring for refugees should be cognizant of the cultural idioms by which suffering is expressed, and the social stigma associated with traumatic experiences and mental illness (Boynton, Bentley, Jackson & Gibbs, 2010; Craig, Jajua, & Warfa, 2009).

This partnership has been sustained by offering ongoing provider and staff trainings across both institutions on the unique needs of refugee populations, and capacity has been built within the local refugee community through the use of CHNs. The CHNs are bi-cultural, multi-lingual paraprofessionals who are medically-trained interpreters able to provide face-to-face interactions with patients in facilitating care coordination, arranging transportation to and from appointments, educating the patient and her family on medications and treatment plans, and conducting home visits when necessary; without the reliance on telephonic interpretation. Furthermore the providers and CHNs are all female which engenders trusting relationships, dialogue and rapport wherein women were less encumbered in discussing sensitive concerns in their native language.

The literature is replete with evidence on the utility of bicultural, multi-lingual paraprofessionals in mental health services in building trust, respect, and mutual understanding in working with refugee populations to mitigate the challenges of this medically complex and vulnerable population (Musser-Granski, & Carrillo, 1997). Bicultural interpreters enhance patient-provider communication, in that while based in the host society, they share not only a language, but a common set of cultural beliefs with the patient. This enables them to be more reflective, thus enhancing their work as patients feel freer to talk about their cultural and religious beliefs (Tribe, 1999). Moreover, among non-homogenous East and Southeast Asian immigrant and refugee groups possessing differing health beliefs, it has been shown that perceived access to culturally, linguistically, and gender appropriate health care was among the main factors influencing attitudes toward seeking professional help (Fung, & Wong, 2007).

There are a few limitations of this initiative, namely the socio-cultural influences on refugee women’s receptivity to mental health care. Among the 13 women who screened positive but were not enrolled in mental health services, six (46.2%) declined care. Some of the factors which may have influenced women’s ability to be screened effectively and/or referred for care included the following: not perceiving a need for mental health care, indicating that symptoms had resolved by the time of mental health services appointment, responding negatively on the RHS-15 despite an overt display of symptomatology as perceived by the provider, declining mental health evaluation due to socio-cultural stigma, perception that seeking mental health care would result in children being removed from the home and/or precipitate marital strain, and reluctance to seek care outside of familiar health care surroundings and staff where trust had already been established. It has been shown that refugees may avoid health care due to the uncertainty associated with interacting with the health care system, and the unclear role they perceive government agencies playing in health care that could compromise their freedom or immigration status (Hollifield, 2004). Moreover, concerns over social stigma may have introduced social desirability bias among participants who may have screened negative despite the overt display of symptoms. This may have been further heightened by the fact that the RHS-15 was verbally administered with the assistance of a CHN due to the presence of extremely low literacy among our patient population. The notion of introducing social desirability bias due to mental health being highly stigmatized, has also been reported in the literature among Somali refugees (Henning-Smith, et al., 2013).

While every effort was made to verbally administer the RHS-15 individually and confidentially to patients without the presence of family members or friends, it was not always possible. At times, patients’ spouses either influenced the patients’ responses, or responded on behalf of the patient even with the CHN present providing appropriate interpretation. A qualitative study of Asian immigrant communities in Australia identified factors influencing access to mental health care, which revealed an unwillingness to access help from mainstream services, with stigma and shame being key factors influencing their reluctance (Wynaden, Chapman, Orb, McGowan, Zeeman, & Yeak, 2005). In addition, studies have identified the underutilization of mental health services as also influenced by the perception of mental health disorders as somatic illness, and related to family discord, social pressure, poor physical health, and adverse life events (Hollifield, 2004).

There were also language barriers wherein the extent of English proficiency was not assessed among those patients for whom English was a second language, but who chose to complete the RHS-15 orally in English. Moreover due to the nature of an extremely busy obstetrics and gynecology practice, and the need to verbally administer the RHS-15 in the preferred language of the patient, the CHNs were not always available to facilitate the administration of the RHS-15. Due to the extremely low literacy (in English as well as their native languages), self-administration of the RHS-15 in this patient population was not feasible. Moreover, there was a limitation in the number of available languages of the RHS-15 as 47 (21.3%) women eligible for screening were unable to complete the screening due to its unavailability in such languages as Amharic, Farsi, French, Swahili, Kirundi, and Oromo at the time of program implementation. Lastly, among the seven women who screened positive on the RHS-15 but lacked health insurance, and were thereby unable to be referred for further mental health evaluation, efforts were made to secure alternative behavioral health resources.

Preliminary findings on the first seven months of the implementation of the RHS-15 in a refugee-focused obstetric and gynecologic clinic in partnership with a behavioral health agency have been described. The next steps in the continuation of this initiative are to track longitudinal outcomes in mental health diagnoses and continuity of care among women who screen positive on the RHS-15. Research has shown mental health services may not provide appropriate support to women with postpartum depression (O’Mahony, & Donnelly, 2010). Hence the association of the RHS-15 with adequacy of prenatal care utilization, obstetric and neonatal outcomes, postpartum depression, and whether changes in the RHS-15 occur over time and with subsequent pregnancies will be assessed. Furthermore, future studies will explore whether correlations exist with RHS-15 scores and ethnicity, age, length of time in the U.S., health status, and social support. Of note, an incidental finding observed with this initiative was the comparison between the 30 Iraqi and 33 Burmese women who completed the RHS-15 (26.8% and 29.5% of the total sample, respectively). Among the Iraqi women, 46.7% scored positive while only 3% scored positive among the Burmese. This is consistent with ethnic variability in the initial RHS-15 validation study (Hollifield et al., 2013). To what extent unique cultural attributes and/or refugee experiences may influence RHS-15 scores and receptivity to seek mental health services, requires future exploration with qualitative studies.

There is a need for community-partnered, culturally-tailored interventions to provide health promotion education, dispel myths and reduce the stigma of mental health, while accentuating asset-based, strength models of resiliency and community social support. Positive attributes such as strong family relations, community-centered values, sharing within the cultural unit, and resiliency have been shown to contribute towards coping and problem-solving during very difficult circumstances (O’Mahony, & Donnelly, 2010). There is a dearth of empirical evidence of refugee-specific interventions which have garnered consistently strong effects due to varying factors including: the design of the intervention, its social and cultural suitability, appropriateness for patients at a particular stage of resettlement, the cultural competence of service providers, the measurability of anticipated outcomes, and the reliability and validity of instruments across different cultural and ethnic groups (Murray, Davison, & Schweitzer, 2010). Moreover there has been limited research to date on refugee women’s social support needs, the barriers they experience and their preferred support interventions (O’Mahony, & Donnelly, 2010). Qualitative research methods would help elucidate the socio-cultural context and complexities of refugee women’s pre- and post-migratory experiences as it impacts not only women’s reproductive health, but the receptivity to accessing mental health services. There is growing interest in the integration or co-location of primary care with behavioral health services to enhance mental health services as a best practice model for improving the recognition of and quality of care for mental illness (Feldman, & Feldman, 2013). However longitudinal interventional trials are needed targeting newly arrived refugee populations. In addition, this study may also have implications for screening refugees for mental health concerns who are seeking other types of medical care or other types of services. Moreover, sustainable interdisciplinary models of care are necessary which support an integrated approach that incorporates not only multi-disciplinary health care providers, but intensive care coordination and case management, trusted, gender-matched, patient health navigators and interpreters, as well as community capacity-building and empowerment.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our invaluable partnership with Pathways to Wellness, its Director, Beth Farmer;Site Director, Junko Yamazaki;and Evaluation and Outreach Coordinators, Sasha Verbillis-Kolp and Tsegaba Woldehaimanot. We appreciate their ground-breaking work in the development and validation of the RHS-15 and their ongoing efforts to expand the breadth of languages available for the RHS-15. We sincerely appreciate the incredible partnership of Jewish Family and Children Services, and want to acknowledge the tireless commitment and dedication of the Cultural Health Navigators of the Refugee Women’s Health Clinic: Owliya Abdallah, Nahida Abdul-Razzaq, Lilian Ferdinand, Daisy Kone, and Medical Assistant, Asheraka Boru, as well as our graduate students: Daniel Kelly and Deborah Monninger, who greatly assisted in the coordination and streamlining of screening and referral processes. Data analysis and manuscript development were supported by training funds from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health (NIMHD/NIH), award P20 MD002316 (F. Marsiglia, P.I.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMHD or the NIH.

Contributor Information

Crista E. Johnson-Agbakwu, Email: cejohn11@asu.edu.

Jennifer Allen, Email: jlallen6@asu.edu.

Jeanne F. Nizigiyimana, Email: jeanne_nizigiyimana@dmgaz.org.

Glenda Ramirez, Email: Glenda.Ramirez@mihs.org.

Michael Hollifield, Email: mhollifield@pire.org.

References

- Barnes D. Mental health screening in a refugee population: A program report. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3:141–149. doi: 10.1023/A:1011337121751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton L, Bentley J, Jackson J, Gibbs T. The role of stigma and state in the mental health of Somalis. J Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16(4):265–268. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000386914.85182.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for mental health screening during the domestic medical examination for newly arrived refugees. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/guidelines/domestic/mental-health-screening-guidelines.html.

- Craig T, Jajua P, Warfa N. Mental health care needs of refugees. Psychiatry. 2009;5(11):405–408. doi: 10.1016/j.mppsy.2009.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson G, Murray K, Schweitzer R. Review of refugee mental health and well-being: Australian perspectives. Australian Psychologist. 2008;43s:160–174. doi: 10.1080/0050060802163041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly T, Hwang J, Este D, Ewashen C, Adair C, Clinton M. If I was going to kill myself, I wouldn’t be calling you. I am asking for help: Challenges influencing immigrant and refugee women’s mental health. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2011;32:279–290. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2010.550383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essen B, Hanson B, Ostergren P, Lindquist P, Gudmundsson S. Increased perinatal mortality among sub-Saharan immigrants in a city population in Sweden. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2000;79:737–43. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2000.079009737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M, Feldman S. The primary care behaviorist: A new approach to medical/behavioral integration. Journal General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(3):331–332. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2330-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung K, Wong YL. Factors influencing attitudes towards seeking professional help among east and southeast Asian immigrant and refugee women. International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2007;53(3):216–231. doi: 10.1177/0020764006074541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon A, Tuck J, Barkun L. A Systematic review of questionnaires measuring the health of resettling refugee women. Health Care for Women International. 2004;25:111–149. doi: 10.1080/07399330490267503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith C, Shippee T, McAlpine D, Hardeman R, Farah F. Stigma, discrimination, or symptomatology differences in self-reported mental health between US-born and Somalia-born Black Americans. American Journal Public Health. 2013;103(5):861–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Warner T, Lian N, Krakow B, Jenkins J, Kesler J, Westermeyer J. Measuring trauma and health status in refugees: A critical review. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:611–621. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M. Building new bridges in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2004;26:253–255. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Warner T, Jenkins J, Sinclair-Lian N, Krakow B, Eckert V, Westermeyer J. Assessing war trauma in refugees: properties of the comprehensive trauma inventory-104. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2006;19(4):527–540. doi: 10.1002/jts.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollifield M, Verbillis-Kolp S, Farmer B, Toolson E, Woldehaimanot T, Yamazaki J, SooHoo J. The Refugee Health Screener-15 (RHS-15): development and validation of an instrument for anxiety, depression, and PTSD in refugees. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2013;35(2):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer L, Narasiah L, Munoz M, Rashid M, Ryder A, Guzder J, Pottie K. Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. Commonwealth Magistrates’ and Judges’ Association. 2011;183:E959–E966. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray K, Davidson G, Schweitzer R. Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: best practices and recommendations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;4(80):576–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser-Granski J, Carrillo D. The use of bilingual, bicultural paraprofessionals in mental health services: issues for hiring, training, and supervision. Community Mental Health Journal. 1997;33(1):51–59. doi: 10.1023/a:1022417211254. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/article/10.1023%2FA%3A1022417211254?LI=true#page-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Refugee Resettlement. Refugee arrival data. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/orr/resource/fiscal-year-2012-refugee-arrivals.

- O’Mahony J, Donnelly T. Immigrant and refugee women’s post-partum depression and help-seeking experiences and access to care: a review and analysis of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2010;17:917–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathways to Wellness. Refugee Health Screener-15: Development and Use of the RHS-15. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.lcsnw.org/pathways/index.html.

- Redwood-Campbell L, Thind H, Howard M, Koteles J, Fowler N, Kaczorowski J. Understanding the health of refugee women in host countries: Lessons from the Kosovar re-settlement in Canada. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. 2008;23:322–327. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00005951. Retrieved from http://www.pdm.medicine.wisc.edu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Brough M, Vromans L, Asic-Kobe M. Mental health of newly arrived Burmese refugees in Australia: contributions of pre-migration and post-migration experinence. Australian and New Zealand Journal Psychiatry. 2011;45:299–307. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.543412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel J, Horan S, Teferra T. Health and healthcare status of African-born residents of metropolitan washington, dc. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2001;3:213–224. doi: 10.1023/A:1012231712455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E, Yanni E, Pezzi C, Guterbock M, Rothney E, Harton E, Burke H. Physical and mental health status of Iraqi refugees resettled in the United States. Journal Immigrant Minority Health. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9893-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribe R. Bridging the gap or damming the flow? Some observations on using interpreters/bicultural workers when working with refugee clients, many of whom have been tortured. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1999;72:567–576. doi: 10.1348/000711299160130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Global Trends. 2011a Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/statistics.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR Resettlement Handbook. 2011b Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/4a2ccf4c6.html.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Resettlement and women-at-risk: can the risk be reduced? UNHCR Regional Office for the USA and the Caribbean. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.unhcrwashington.org/site/c.ckLQI5NPIgJ2G/b.8542409/k.D5BA/Resettlement_and_WomenatRisk.htm.

- Wynaden D, Chapman R, Orb A, McGowan S, Zeeman Z, Yeak S. Factors that influence Asian communities’ access to mental health care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2005;14:88–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]