Abstract

Tropones and tropolones are an important class of seven-membered non-benzenoid aromatic compounds. They can be prepared directly by oxidation of seven-membered rings. They can also be derived from cyclization or cycloaddition of appropriate precursors followed by elimination or rearrangement. This review discusses the types of naturally occurring tropones and tropolones and outlines important methods developed for the synthesis of tropone and tropolone natural products.

1. Introduction

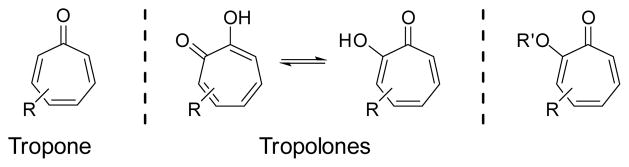

Tropones and tropolones refer to non-benzenoid seven-membered aromatic compounds with a carbonyl group (Scheme 1), which are also called troponoids or tropolonoids. Although the simplest tropone (R = H) is not a naturally occurring compound, it has been used as a basic building block in various cycloadditions.1–11 The tropone moiety has only been found in several natural products. However, tropolones with a α-hydroxy or alkoxyl group (tropolone ether) are much more common in nature. Many tropolones have multiple hydroxy or alkoxyl groups in addition to the one on the α-position. The simplest tropolone (R = R′ = H) was isolated from Pseudomonas lindbergii. ATCC 31099 12 and Pseudomonas plantarii. ATCC 43733.13 To date, about 200 naturally occurring tropolones have been identified.14–15 Most of the tropolones were isolated from plants and fungi. They have interesting chemical structures and biological activities such as anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, anti-tumor and anti-viral activities. Recent data showed that tropolones could be potent and selective inhibitors for enzymes with zinc-cofactor.16–17

Scheme 1.

Tropones, tropolones and related compounds

The study of tropones and tropolones dates back to the 1940s, when Dewar first proposed seven-membered aromatic structures for colchicines and stipitatic acid (Scheme 2).18–19 A few years later, the structures of thujaplicins were determined as isomers of isopropyl tropolones.20–21 During the same time period, Nozoe independently assigned the correct structure for β-thujaplicin (hinokitiol).22–23 Two reviews on the structure, biological activity and biosynthesis of tropones and tropolones were recently published.14–15 Numerous synthetic methods have been developed for the synthesis of tropones and tropolones and some of them were discussed in early reviews published before 1991.24–27 Three recent reviews focused on special classes of compounds, such as colchicine,28 the five tropones derived from the Cephalotaxus species,29 and α-hydroxytropolones (dihydroxytropones).30

Scheme 2.

Tropolones discovered in early days

Naturally occurring tropones are relatively rare. The simplest tropone is nezukone, isolated from Thujastandishii (Scheme 3).31–33 Instead of hydroxy groups, some tropones have an amino or thiogroup. For example, manicoline A, isolated from Dulaciaguianensis, has an α-amino group.34 Antibiotics tropodithietic acid and its valence tautomer, thiotropocin, have either thio-substituents or a carbon-sulfur double bond.35–37 A number of related antibiotics have also been isolated.38–39

Scheme 3.

Examples of mono- and bicyclic naturally occurring tropones and related compounds

Diterpenoid tropones have a unique fused tetracyclic carbon skeleton (Scheme 4). Five members of them have been isolated and characterized thus far: harringtonolide, hainanolidol, for tunolide A, for tunolide B and 10-hydroxyhainanolidol. Buta’s group first isolated harringtonolide in 1978, followed by Sun’s group in 1979, from the seeds of Cephalotaxus harringtonia and the bark of the related Chinese species Cephalotaxus hainanensis.40–41 Sun also reported the isolation of hainanolidol, which was proposed as the precursor for harringtonolide.41 Harringtonolide was first found to inhibit the growth of beans and tobacco.40 Subsequently, more interesting biological activities have been discovered, such as antiviral, antifungal and anticancer activities.41–42 Recently, significant antitumor activity was reported with an IC50 = 43 nM in KB cancer cells.43 Fortunolides A and B were isolated from the stems and needles of C. fortunei var. alpina in 1999.44 11-Hydroxyhainanolidol was isolated from C. koreana in 2007.45

Scheme 4.

Norditerpene tropones

Pareitropone, another tropone-containing natural product, will be discussed later together with its tropolone congeners.

Benzotropolones contain a benzo-fused tropolone core (Scheme 5). The most studied member of this family is purpurogallin, a reddish crystalline substance isolated from nutgalls and oak bark, which was used as anti-oxidant in non-edible oil, fuels and lubricants.46–47 The structure of purpurogallin was established by single crystal x-ray analysis.48 It also inhibited the HIV-1 integrase activity through a metal chelation mechanism.49 This compound was also used as a cardio-protector due to its antioxidant property.50

Scheme 5.

Examples of benzotropolones and some theaflavin derivatives

Theaflavins are found in black tea leaves, in which the compounds account for 2–4 wt% of the dry black tea.51 This family of compounds also has a benzotropolone skeleton and the benzene unit is often part of a flavone moiety. Theaflavins are produced in the process of fermenting the leaves of Camellia sinensis from co-oxidation of selected pairs of catechins, which exist in green tea leaves. The theaflavin was first isolated from the black tea leaves in 1957.52 Since then, extensive studies have been carried out on their chemical structures, biological activities and other properties. Numerous biological activities have been discovered, such as anti-oxidant, anti-pathogenic, anti-cancer, preventing heart diseases and preventing hypertension and diabetes.53–57

The tropoisoquinoline and tropoloisoquinoline compounds were isolated from the Menispermaceae plants Cissampelospareira and Abutagrandifolia, and proven to have cytotoxicity in selected assays.58–63 Six members from this family of tropone/tropolone alkaloids have been characterized including grandirubrine, imerubrine, isoimerubrine, pareirubrine A, pareirubrine B and pareitropone (Scheme 6).58,60–64 Among the family, pareitropone showed the greatest cytotoxicity in leukemia P388 cell lines (IC50 = 0.8 ng/mL).63

Scheme 6.

Tropoisoquinolines and tropoloisoquinolines

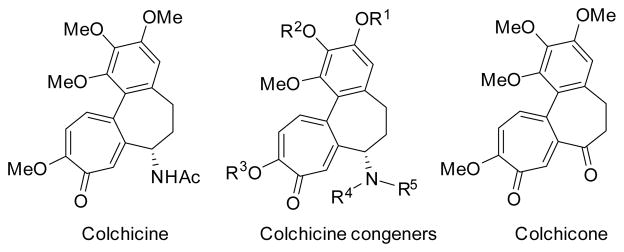

Colchicine is the most extensively studied member of tropolones (Scheme 7). It was first isolated from the genus Colchicum by Pelletier and Caventou in 1820.65 The Colchicum is common in Europe and North Africa, where it was used as a poison as well as a treatment of acute gout. After its isolation, colchicine was purified and named by Geiger in 183366 and its structure was assigned by Dewar in 1945.19 Colchicine was found to bind to tubulin and inhibit microtubule polymerization. The FDA approved colchicine in 2009 as a mono-therapy for acute gout flares, familial Mediterranean fever and prophylaxis of gout flares. It was also used for inducing polyploidy in plant cells during cellular division. Although colchicine has significant cytotoxic activity, poor selectivity limited its clinical use for the treatment of cancer. A large number of naturally occurring colchicine congeners have been identified.15 A small number of non-nitrogen containing colchicine derivatives, such as colchicone, have also been reported.67

Scheme 7.

Colchicine and its congeners

Most tropolones are the secondary metabolites of plants and fungi and their biosynthesis has recently been reviewed.14–15,68 The biosynthesis of many tropolones, such as thujaplicins, involves the terpene pathways. The most accepted biosynthetic pathway for colchicine and related alkaloids was proposed by Battersby.69–74 Colchicineis derived from L-tyrosine and L-phenylalanine and its biosynthesis involves a series of CYP450-mediated oxidation and rearrangement reactions. Nay recently proposed a biosynthetic pathway for the complex norditerpene tropones based on the biosynthesis of the abietanes.29 The seven-membered tropone was proposed to originate from intramolecular cyclopropanation of an aromatic ring followed by Cope rearrangement.

The biosynthetic pathways of benzotroponoid systems involve oxidation and coupling of polyphenols.75–77 Nakatsuka studied the details of the biomimetic synthesis of benzotropolone 8-8 from 5-methylpyrogallol 8-1 and 4-methyl-o-quinone 8-2, derived from oxidation mediated by Fetizon’s reagent (Ag2CO3/celite) as shown in Scheme 8.78 When phenol 8-1 was reacted quinone 8-2 in methylenechloride, bicyclo [3.2.1] intermediate 8-6 was formed in 68% yield as colorless crystals, which was proposed as the key intermediate in previous biosynthesis or biomimetic synthesis of benzotropolones.79–81 Intermediate 8-6 was converted to tropolone 8-8 in nearly quantitative yield in water at room temperature after 30 min.

Scheme 8.

Biomimetic synthesis of benzotropolones

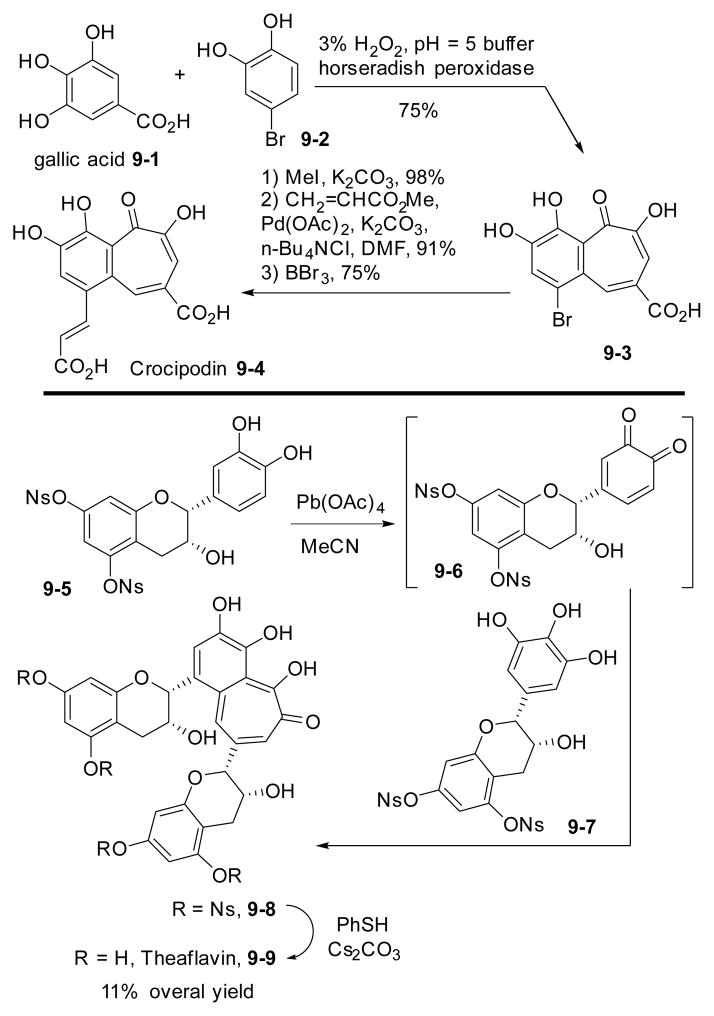

Using horseradish peroxidase or Pb(OAc)4 as the oxidant, biomimetic syntheses crocipodin 9-482 and theaflavin 9-983 have been accomplished starting from the corresponding polyphenol precursors 9-1, 9-2, 9-5, and 9-7 (Scheme 9). Previously, Sang’s group prepared a series of compounds with a benzotropolone skeleton including theaflavin by the horseradish peroxidase-mediated coupling of unprotected polyphenols.84

Scheme 9.

Biomimetic synthesis of crocipodin and theaflavin

Extensive research has been conducted towards chemical synthesis of tropones and tropolones. This review summarizes synthetic methods published before the end of 2013. It begins with synthetic methods that can convert simple seven-membered rings to tropones and tropolones, followed by the synthesis of tropone- and tropolone-containing natural products. The subsequent section was organized by how the 7-membered rings were formed. Although seven-membered ring syntheses have been reviewed several times, these reviews often focus on one type of method, such as the [4+3] cycloaddition,85–87 [5+2] cycloaddition,88–89 or other reactions.90–91 A recent review on synthetic strategies to access seven-membered carbocycles in natural products only discussed the total synthesis of a few tropone- and tropolone-containing natural products including pareitropone, imerubrine, isoimerubrine and grandirubrine.92

2. Conversion of Simple Seven-membered Ring to Tropones and Tropolones

In earlier days, most synthetic efforts for tropones and tropolones focused on direct oxidation of substituted 7-membered rings.24 These methods have been used for decades to access the tropone and tropolone structures.

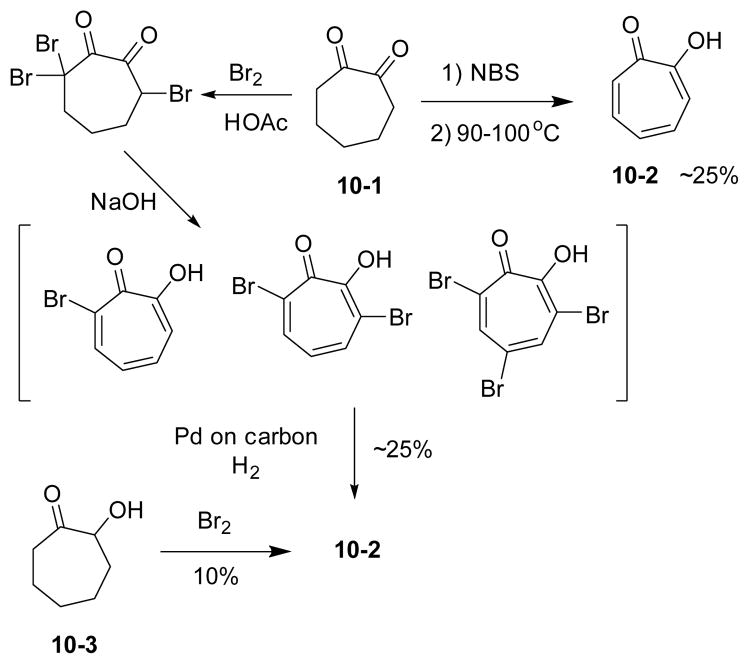

2.1 Oxidation via halogenations followed by elimination

The oxidation by halogenation method was initially developed by Cook and has been most widely used in the synthesis of tropones and tropolones.93 It started with halogenation, most commonly bromination, followed by elimination to afford halogenated tropone derivatives. The distribution of bromotropolones is highly dependent on the amount of bromine. The bromotropolones could undergo hydrogenolysis in the presence of a palladium-charcoal catalyst to give the tropolone product. Compared to bromine, the reaction with NBS could provide tropolone 10-2 directly together with other brominated tropolones. The above halogenation/elimination methods are applicable to various 7-membered ring substrates including 1,2-cycloheptanediones (e.g. 10-1), 2-hydroxycycloheptanones (e.g. 10-3), cycloheptanones, cycloheptenones and cycloheptadienones. When 2-hydroxycycloheptanone 10-3 was employed as substrates, the reaction afforded tropolone 10-2 as the only product in 10% yield without any other bromo-derivatives (Scheme 10).94

Scheme 10.

Oxidation of 1,2-cycloheptanedione and 2-hydroxycycloheptanone by bromine and NBS

Bromination of cycloheptenone 11-1 afforded tribromotropone 11-2 only, which could undergo further hydrogenolysis to yield tropone 11-3 (Scheme 11).24,95 Bromination of cycloheptanone 11-4 led to a mixture of brominated derivatives. The bromination/elimination method was applied to the synthesis of natural product nezukone by starting with β-isopropyl substituted cycloheptanone.96

Scheme 11.

Oxidation of cycloheptanone to tropone by Br2

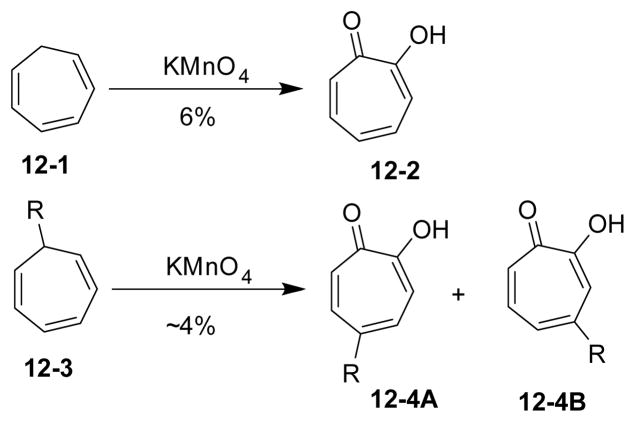

2.2 Oxidation of cyclohepta-1,3,5-triene

Doering and Knox reported an oxidation of cyclohepta-1,3,5-triene 12-1 to tropolone 12-2 by permanganate in 1950, albeit in a low yield (Scheme 12).97–99 Two isomers 12-4A/B were identified for substituted cycloheptatrienes.

Scheme 12.

Oxidation of cycloheptatriene by permanganate

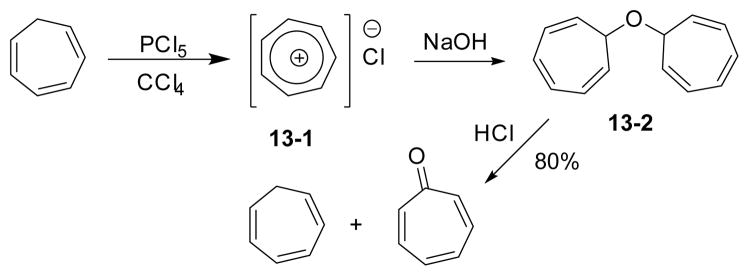

A method to convert cycloheptatriene to tropone via ditropyl ether 13-2 was reported in 1960 (Scheme 13).100 Cycloheptatriene was first oxidized by phosphorus pentachloride to tropylium cation 13-1. In the presence of NaOH, a newly formed cyclohepta-2,4,6-trienol could be trapped by another tropylium ion to afford a ditropyl ether. Treatment of this ditropyl ether with acid led to one molecule of tropone along with one molecule of cycloheptatriene.

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of tropone via ditropyl ether

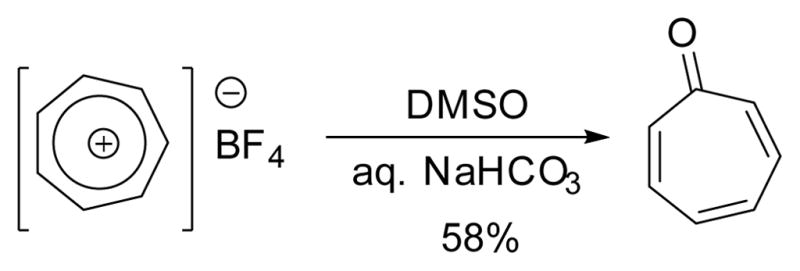

Tropone could also be prepared by treating tropylium ion with DMSO (Scheme 14).101–102

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of tropone from tropylium ion

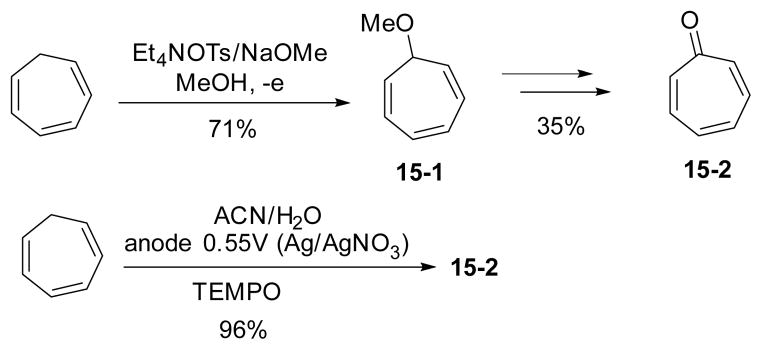

Shono’s group extensively studied the electrochemical oxidation of cycloheptatrienes to tropones and tropolones (Scheme 15).103–106 The methoxycycloheptatriene intermediate 15-1 was first formed. A series of isomerization, further electrochemical oxidation and hydrolysis led to the formation of tropone. Substituted tropones and tropolones were also prepared by this method. Cycloheptatrienes could also be oxidized directly to tropones in the presence of TEMPO catalyst under electrochemical conditions.107

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of tropone by electrochemical oxidation

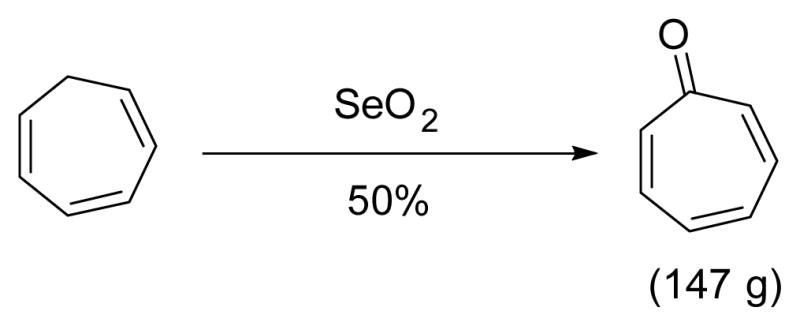

Direct conversion of cycloheptatriene to tropone could also be achieved by oxidation usingSeO2 in over 100 gram scale reactions (Scheme 16).108

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of tropone by SeO2 oxidation

2.3 Oxidation by singlet oxygen via endoperoxide

Cycloheptatrienes could react with singlet oxygen to form different isomeric endoperoxides (e.g. 17-2A/B, Scheme 17).109–112 Some of them could be converted to tropones via Kornblum-DeLaMare rearrangement113 followed by elimination.114 This was applied to the synthesis of stipitatic acid isomers as discussed in later sections.115 Tropolones could also be prepared with appropriate alkoxy substituents on the cycloheptatriene substrate.116–117

Scheme 17.

Synthesis of tropones from endoperoxides

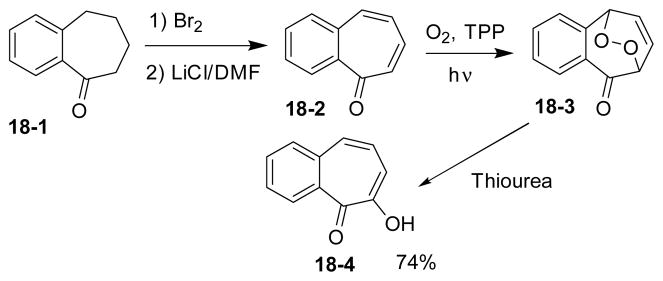

Oxidation of benzotropone 18-2 via endoperoxide intermediate 18-3 afforded tropolone 18-4 selectively (Scheme 18).118 Benzotropone 18-2 was prepared by halogen-mediated oxidation of 18-1 followed by elimination. The TPP-sensitized photo-oxygenation provided the bicyclic endoperoxide intermediate 18-3, which was reduced by thiourea in methanol to generate benzotropolone 18-4.

Scheme 18.

Oxidation of benzotropone to benzotropolone

2.4 Oxidation via dehydrogenation

Direct oxidative dehydrogenation of cycloheptanones or cycloheptenones is another obvious strategy for the preparation of tropones. However, limited examples were found in the literature using DDQ as the oxidant119 or transition metal complex as the dehydrogenation catalyst.120 Nicolaou showed one such example using IBX as the oxidant (Scheme 19).121–122 Using a water-soluble ortho-iodobenzoic acid derivative AIBX, Zhang also prepared a benzotropone.123

Scheme 19.

Dehydrogenative oxidation by hypervalent iodine reagents

3. Synthesis of naturally occurring tropones and tropolones

In the following sections, we will focus on how the tropone or tropolone moiety in natural products was prepared. They can be generated from commercially available seven-membered rings or derived from various cyclization and cycloaddition reactions.

3.1 Conversion of commercially available seven-membered rings to tropones or tropolones

Tropolone derivatives can be prepared by Friedel-Crafts acylation of tropone iron tricarbonyl complex 20-1, available in 85% yield by irradiation of tropone with iron pentacarbonyl in toluene (Scheme 20).124 A mixture of tautomeric acetyltropone iron complexes (20-2A/B) was often obtained. Natural products β-thujaplicin and dolabrin were prepared by reacting the resulting acetyltropone iron complex with 2-diazopropane, deacetylation, oxidative decomplexation and α-functionalization.

Scheme 20.

Synthesis of β-thujaplicin and dolabrin

The tropone- or tropolone moiety could be derived from naturally occurring compounds. For example, natural product dolabrin could be prepared from β-thujaplicin via a bromination and elimination sequence (Scheme 21).125

Scheme 21.

Synthesis of dolabrin from β-thujaplicin

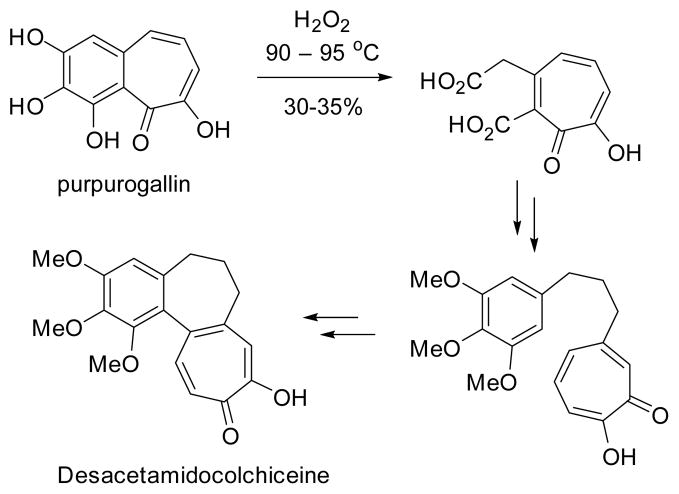

As another example, the tropolone moiety in colchicine was derived from naturally occurring purpurogallin in two formal syntheses of colchicine derivatives (Scheme 22).126–127

Scheme 22.

Formal synthesis of colchicine from purpurogallin

In Nakamura’s synthesis of colchicine, the seven-membered ring was derived from an ester-substituted cycloheptanone 23-2 (Scheme 23).128–129 Cycloheptatriene 23-5, derived from halogenation and elimination of cycloheptene, was converted to the corresponding tropone 23-6 using the hydrolysis of ditropyl ether protocol illustrated in Scheme 13.

Scheme 23.

Synthesis of (±)-colchicine from acycloheptanone

Shono’s group reported a synthesis of β-thujaplicin from substituted cycloheptatrienes (Scheme 24).130 The 1-methoxycycloheptatriene 24-1 and 3-methoxycycloheptatriene 24-2 starting materials were prepared from electrochemical oxidation of cycloheptatrienes followed by thermal rearrangement of the oxidation product 7-methoxycycloheptatriene 15-1 shown in Scheme 15.103 The isopropyl group was introduced to the ring system by electro-reductive alkylation of these methoxycycloheptatrienes. A sequence of bromination followed by elimination then led to the formation of substituted tropone 24-4, which could undergo oxidative α-amination in presence of hydrazine and hydrolysis to form the natural product target. Alternatively, the synthesis of thujaplicin could also be completed by a sequence of hydrolysis, isomerization/epoxidation, dione formation and bromination/elimination from 24-3.

Scheme 24.

Synthesis of thujaplicin by electro-reductive alkylation of substituted cycloheptatrienes

3.2 Formation of the seven-membered ring by cyclization

The seven-membered ring in nezukone, one of the simplest naturally occurring tropones, could be prepared by TiCl4-mediated cyclization of 25-1 (Scheme 25).131 Conversion of chloride 25-2 to ketone 25-3 through a cycloheptylstannane intermediate followed by bromination and elimination afforded the tropone moiety and completed the synthesis.

Scheme 25.

Synthesis of nezukone via cyclization

In 1959, Van Tamelen reported a synthesis of colchicine by forming the tropolone ring via acyloin cyclization (Scheme 26).132–133 In the presence of sodium metal in liquid ammonia, acyloin condensation provided a tetracyclic hemiketal, which was oxidized by cupric acetate in methanol to ketone 26-2. Exposing the hemiketal to toluenesulfonic acid in refluxing benzene led to opening the epoxy bridge and then dehydration. The crude enedione was then oxidized by NBS in refluxing chloroform to yield desacetamidocolchicine derivative 26-3, which could be converted to colchicine.

Scheme 26.

Synthesis of (±)-colchicine by acyloin cyclization

In 1965, Toromanoff reported a synthesis of desacetamidocolchicine using a strategy similar to Van Tamelen (Scheme 27).134 The use of the cyanoesterin 27-1 rather than the corresponding diester avoids the regioselectivity issue in the cyclization step. A sequential oxygenation and oxidation with NBS led to the formation of tropolone ring.

Scheme 27.

Formal synthesis of colchicine derivative by cyclization of a cycloheptatriene

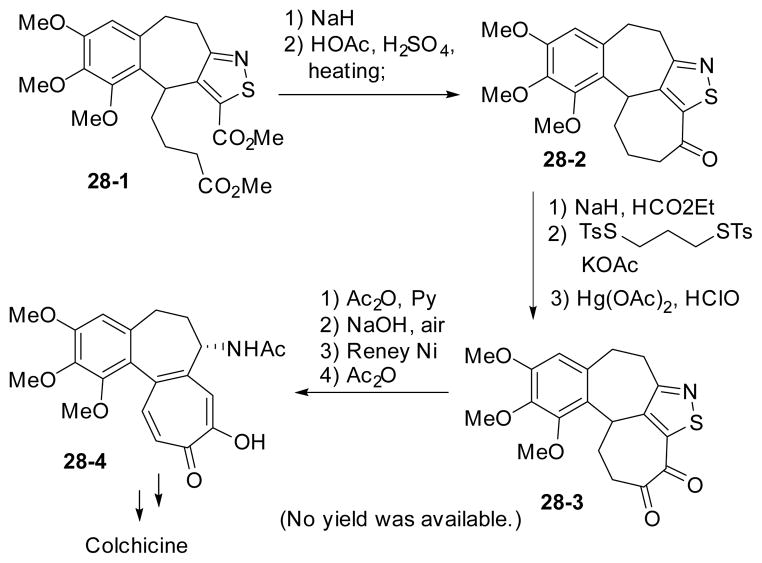

In 1963, Woodward presented his synthesis of colchicine in the Harvey Lecture (Scheme 28).28,135 The seven-membered tropolone ring was derived from Dieckmann condensation of 28-1. The challenging nitrogen functionality was introduced as an isothiazole ring, which is critical for the formation of both seven-membered rings. The rest of the C=C bonds and oxygen functionality were installed via diketone intermediate 28-3. The isothiazole ring was converted to amine by reduction with Raney nickel. No yield was available for each step of the synthesis.

Scheme 28.

Woodward’s synthesis of (±)-colchicine

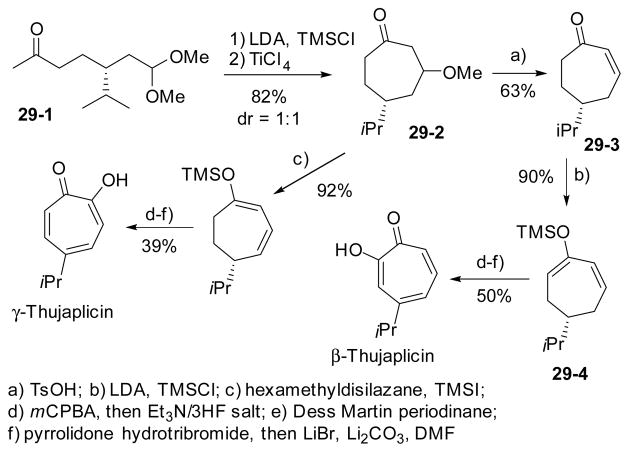

Starting with limonene, Kitahara’s group realized a divergent synthesis of both β- and γ-thujaplicins (Scheme 29).136 The seven-membered ring was obtained by TiCl4-mediated cyclization of a ketone enolate to dimethyl acetal in 29-1, derived from limonene. A series of elimination and oxidation reactions then led to the formation of both tropolones regioselectively. The last step of the tropolone formation involved bromination and elimination.

Scheme 29.

Divergent regioselective synthesis of thujaplicins

In 1989, Kakisawa’s group completed the synthesis of salviolone (Scheme 30),137–138 a cytotoxic benzotropolone bisnorditerpene.139 Although the tropolone ring was constructed quickly by a double aldol condensation reaction, the yield and regioselectivity of this key step are relatively low.

Scheme 30.

Synthesis of salviolone by double aldol condensation

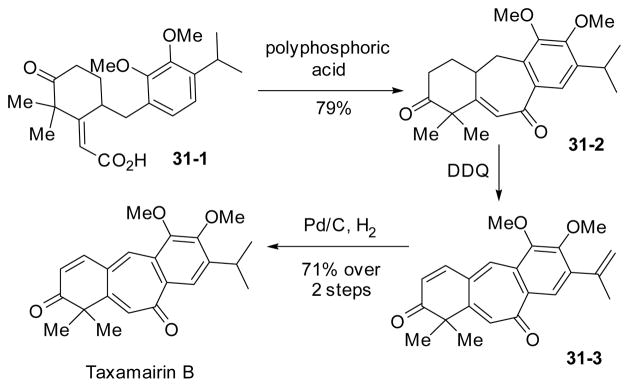

The synthesis of taxamairin B140–141 was completed by Pan’s group (Scheme 31).142–143 The seven-membered ring in benzotropone was cyclized by an acid-mediated Friedel-Crafts acylation of 31-1. Three double bonds in 31-3 were introduced by DDQ-mediated dehydrogenation of 31-2. The isopropyl group was recovered by hydrogenation.

Scheme 31.

Synthesis of taxamairin B by Friedel-Crafts acylation

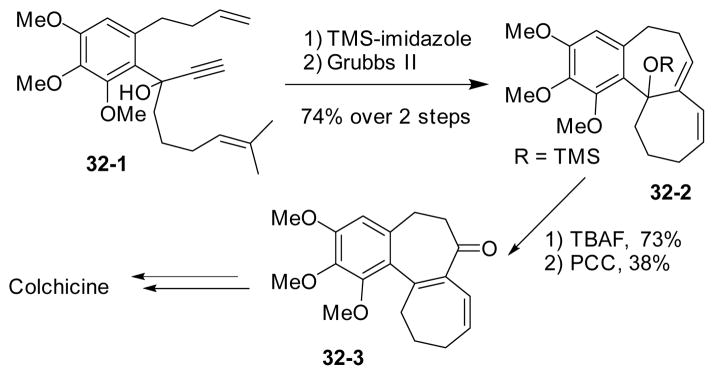

In 2007, Hanna’s group applied a dienyne tandem ring-closing metathesis reaction144–145 to the synthesis of the tricyclic core of colchicine (Scheme 32).146 Two 7-membered rings in 32-2 were formed in this tandem reaction. After removing the TMS group and oxidation/transposition mediated by PCC, known dienone intermediate 32-3 was prepared. Following Wenkert’s147 and Nakamura’s128–129 procedures, this dienone intermediate could be converted to colchicine.

Scheme 32.

Formal synthesis of colchicine by dienyne metathesis

Recently, ring-closing metathesis of dienes was also applied to the synthesis of 3,4-benzotropolones (Scheme 33).148 One example of enyne metathesis was also realized for the synthesis of vinylbenzotropolones.

Scheme 33.

Synthesis of 3,4-benzotropolones by ring-closing metathesis

3.3 Formation of the seven-membered ring by ring expansion

Among all the synthetic methods for tropones and tropolones, ring expansion of readily available six-membered rings, especially cyclopropanation/ring expansion tandem reactions, was the most often used protocol. A short overview by Reisman on the applications of Buchner reaction (section 3.3.1) to natural product synthesis was recently published.149 Maguire recently reviewed the factors that determine the distribution of norcaradiene and cycloheptatriene in various systems.150 Qin also published a review paper on the application of cyclopropanation strategies to natural product synthesis151 and an account about their own work on the synthesis of indole alkaloids by cyclopropanation.152 the tropone- or tropolone-containing natural products in the following sections were not discussed in these reviews.

3.3.1 Cyclopropanation of arenes with diazo- compounds followed by ring expansion – Buchner reaction

Buchner first reported the cyclopropanation of arenes with carbenes derived from diazo compounds for the synthesis of norcaradiene as early as 1885.149,153 Doering and coworkers characterized the products as a mixture of cycloheptatrienes.97,99,154 They and others155 also oxidized the cycloheptatriene products to tropolone derivatives. Benzotropolones were also prepared similarly.156

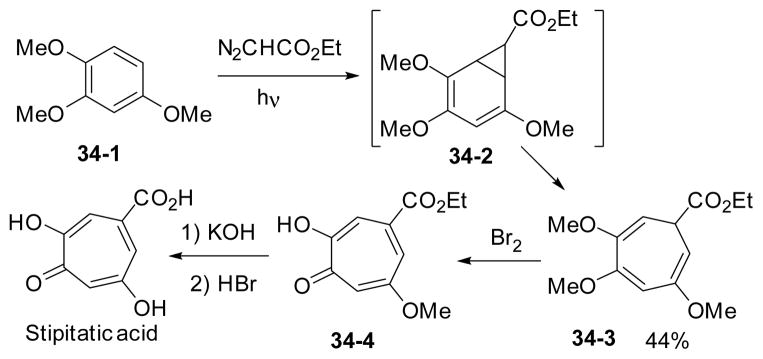

One of the early applications of Buchner reactionin natural product synthesis is Taylor’s synthesis of stipitatic acid (Scheme 34).157 The cyclopropanation of 1,2,4-trimethoxybenzene 34-1 with diazoacetic acid ester under photolytic conditions gave 7-membered cycloheptatriene product 34-3 through the ring expansion of norcaradiene intermediate 34-2. The synthesis was completed after bromination and hydrolysis.

Scheme 34.

Synthesis of stipitatic acid using Buchner reaction

Transition metals, such as rhodium (II) carboxylate, catalyzed the cyclopropanation of alkenes and arenes in a much more efficient process.158–159 In the presence of excess arenes, rhodium (II) catalyzed the decomposition of alkyl diazoacetates, which could then generate cycloheptatrienes at room temperature.

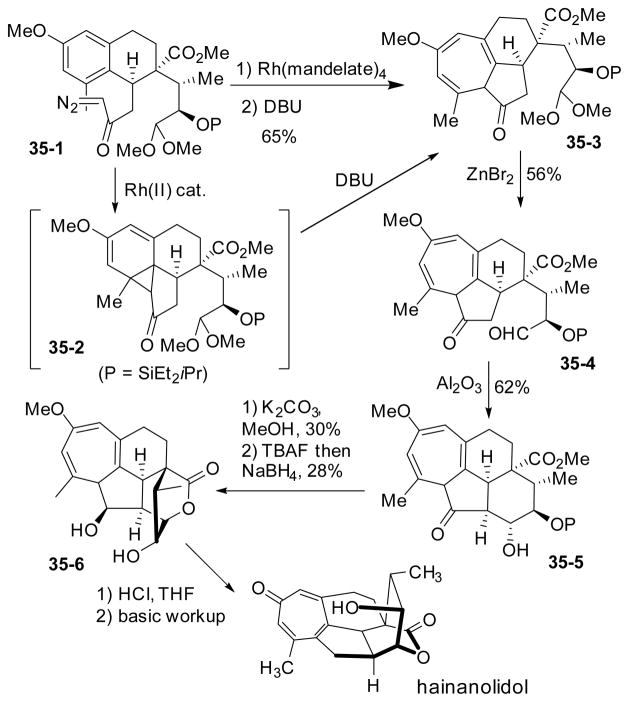

Mander’s group applied the Buchner reaction to the total synthesis of hainanolidol (Scheme 35).160 In the presence of rhodium mandelate, arene cyclopropanation occurred efficiently to afford unstable tetracyclic intermediate 35-2, which was immediately exposed to DBU to give the cycloheptatriene product 35-3. This triene was then converted to natural product hainanolidol after a sequence of aldol reaction, lactonization, elimination and hydrolysis/isomerization. Mander’s group also tried to improve their synthesis of hainanolidol and complete the synthesis of the related bioactive congener, harringtonolide.161–166 However, none of these further efforts led to the completion of harringtonolide.

Scheme 35.

Mander’s synthesis of (±)-hainanolidol

Inspired by Mander’s synthesis, Camp’s group tried to prepare simplified analogues of harringtonolide.167 However, they failed to convert the cycloheptatriene products derived from the Buchner reaction to tropones.

Balci applied the Buchner reaction to the synthesis of stipitatic acid isomers via endoperoxide intermediate 36-3 (Scheme 36).115 A base-mediated Kornblum-DeLaMare rearrangement113 and cobalt meso-tetraphenylporphyrin-catalyzed (CoTPP) rearrangement of this endoperoxide led to isomers of stipitatic acid esters 36-4A/B.

Scheme 36.

Balci’s synthesis of isomers of stipitatic acid esters

3.3.2 Base promoted cyclopropanation followed by ring expansion

In 1959, Eschenmoser finished the first total synthesis of colchicine.168–169 In this synthesis, the tropolone ring was derived from a base promoted intramolecular cyclopropanation of 37-1 followed by ring expansion and oxidation (Scheme 37). It is also interesting to note that the benzene-fused seven-membered ring was prepared from hydrogenation of the tropolone ring in natural product purpurogallin. Although the carbon skeleton was assembled very efficiently, the installation of the rest of the functional groups proved to be difficult. For example, the positions of the oxygen functionalities (carbonyl oxygen and methoxy group) had to be readjusted and the introduction of the acetylamide group required many steps and proceeded with low yields.

Scheme 37.

Eschenmoser’s synthesis of (±)-colchicine

In 1986, Kende reported an efficient method for the synthesis of annulated tropones and tropolones through oxidative cyclization of phenolic nitronates followed by ring expansion and elimination (Scheme 38).170–172 Treatment of phenolic nitroalkane 38-1 with K3Fe(CN)6 in dilute KOH solution provided spirocyclicdienone 38-2 through a stepwise single electron transfer process. Formation of cyclopropane intermediate 38-3 followed by ring expansion of 38-4 afforded tropone 38-5 in good yield.

Scheme 38.

Intramolecular radical cyclization of phenolic nitronates developed by Kende

Cha’s group applied this radical anion coupling strategy to the total synthesis of pareitropone (Scheme 39).173 Exposure of the dihydroquinoline precursor 39-1 to excess amount of K3Fe(CN)6 in dilute KOH solution led to spirocyclicdienone intermediate 39-2, which underwent cyclopropanation, ring expansion and elimination to afford the tropone-containing natural product.

Scheme 39.

Cha’s synthesis of pareitropone

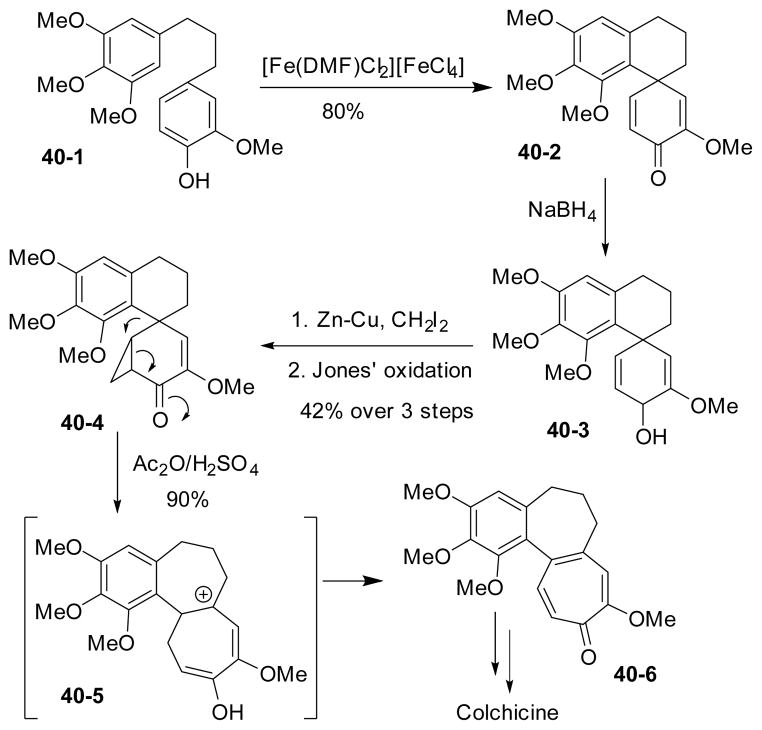

3.3.3 Simmons-Smith cyclopropanation followed by ring expansion

In 1974, Tobinaga and his coworkers reported a synthesis of (±)-colchicine featuring a Simmons-Smith cyclopropanation followed by Jones oxidation and rearrangement to access the tropone moiety and the adjacent seven-membered ring (Scheme 40).174 An intramolecular oxidative phenol coupling reaction provided the spirocyclic intermediate 40-2, which was reduced to allylic alcohol for the Simmons-Smith cyclopropanation. The tricyclic carbon skeleton and the tropone moiety in 40-6 were constructed by Jones oxidation followed by an acid promoted rearrangement. The synthesis then intercepts with Eschenmosers’ at this stage.169

Scheme 40.

Tobinaga’s formal synthesis of (±)-colchicine

The above strategy was also applied to the synthesis of monocyclic tropolones (Scheme 41).175 A sequence of Birch reduction followed by Simmons-Smith cyclopropanation and oxidative rearrangement provided a short synthesis of various substituted tropolones from benzene derivatives.

Scheme 41.

Synthesis of monocyclic tropolones via Simmons-Smith cyclopropanation and ring expansion

3.3.4 Dihalocarbene mediated cyclopropanation followed by ring expansion

In 1968, Birch reported a synthesis of nezukone by reduction of isopropyl anisole 42-1 followed by cyclopropanation and silver-mediated ring expansion (Scheme 42).176 The cyclopropanation was mediated by a dichlorocarbene species derived from chloroform.

Scheme 42.

Synthesis of nezukone via dihalocarbene

In 1978, MacDonald prepared the tropolone moiety in γ-thujaplicin via a sequence of cyclopropanation and ring expansion (Scheme 43).177 The diene substrate 43-2 for cyclopropanation was derived from Birch reduction of phenol derivative 43-1. The cyclopropanation was mediated by sodium trichloroacetate through a dichlorocarbene intermediate. Epoxidation of the remaining olefin followed by an acid catalyzed rearrangement afforded α-chlorotropone intermediate 43-5, which was converted to γ-thujaplicin under acidic conditions.

Scheme 43.

Synthesis of γ-thujaplicin via dihalocarbene

Banwell applied the sequence of cyclopropanation and ring expansion to the synthesis of a number of tropone- and tropolone-containing compounds,178–179 As shown in Scheme 44, cyclopropanation via dihalocarbene followed by ring expansion would lead to the formation of halotropone or halotropolone derivatives, which could undergo cross-coupling to form other tropone- or tropolone-containing compounds, such as β-dolabrin, β-thujaplicin, and β-thujaplicinol.180–181 The synthesis of nezukone involved the formation of alkylidene cyclopropane from halocyclopropane followed by ring expansion.31

Scheme 44.

Halotropones and halotropolones derived from cyclopropanation and ring expansion

The synthesis of stipitatic acid and puberulic acidal so involved dihalocarbene-mediated cyclopropanation followed by ring expansion (Scheme 45).182 The carboxylic acid group was introduced by quenching an alkyllithium intermediate with carbon dioxide at an early stage (from 45-1 to 45-2) for the synthesis of stipitatic acid. A late stage Pd-catalyzed carbonylation of bromotropone 45-7 furnished the carboxylic acid group in the synthesis of puberulic acid.

Scheme 45.

Banwell’s synthesis of stipitatic acid and puberulic acid

In addition to tropolones, polysubstituted tropones have also been prepared from substituted cyclohexanones by this method.183

3.3.5 Sulfur ylide mediated cyclopropanation followed by ring expansion

Evans reported a convergent formal synthesis of (±)-colchicine utilizing a cyclopropane derivative of a quinonemonoketal (Scheme 46).184–185 Addition of an ester enolate to the above quinonemonoketal followed by Friedel-Crafts cyclization afforded spirocyclic intermediate 46-3, which could undergo acid-mediated rearrangement to yield two seven-membered rings in 46-4. Oxidation by DDQ then generated the tropolone moiety in 46-5, which could be converted to advanced colchicine precursors.

Scheme 46.

Evans’ formal synthesis of (±)-colchicine

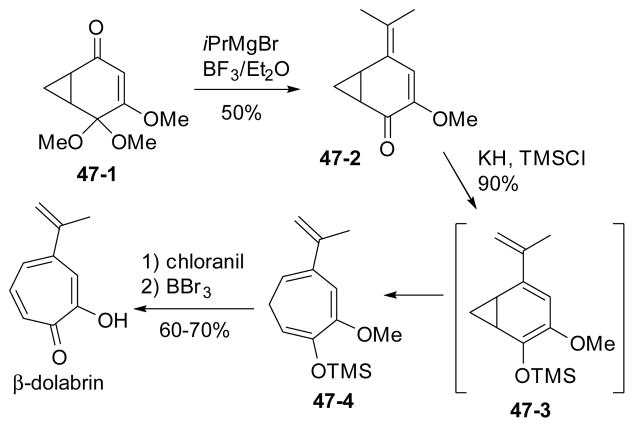

Evans also demonstrated the utility of this strategy in the total synthesis of β-dolabrin (Scheme 47).185 The ring expansion was effected by base via electrocyclic ring opening of enolate 47-3 derived from ketone 47-2.

Scheme 47.

Evans’ total synthesis of β-dolabrin

In 1985, Keith prepared stipitatic acid from a quinone derivative via cyclopropanation and ring expansion (Scheme 48).186 The reaction between the quinone substrate 48-1 and dimethylsulfonium carbomethoxymethylide 48-2 was nearly quantitative.

Scheme 48.

Synthesis of stipitatic acid via cyclopropylquinone

In Banwell’s synthesis of MY3-469 and isopygmaein, a nucleophilic cyclopropanation mediated by a sulfur ylide followed by Lewis acid promoted ring expansion afforded the tropolone core of both natural products (Scheme 49).187

Scheme 49.

Banwell’s synthesis of MY3-469 and isopygmaein by sulfur ylide-mediated cyclopropanation

Banwell also employed the sulfur ylide cyclopropanation/ring expansion strategy in his asymmetric synthesis of colchicine (Scheme 50).188 Exposure of the resulting cyclopropyl ortho-quinonemonoketal 50-2 to excess of TFA promoted the rearrangement to tropolone and intercepts with previous syntheses. This asymmetric synthesis is the cumulative result of a large body of previous work.188–192

Scheme 50.

Banwell’s synthesis of (−)-colchicine by sulfur ylide-mediated cyclopropanation

Later on, Banwell used the same strategy for the synthesis of tropoloisoquinoline alkaloids imerubrine and grandirubrine (Scheme 51).188 The tetracyclic precursor 51-1 for cyclopropanation was prepared in 7 steps. Taylor-McKillop oxidation of the ortho-methoxy phenol moiety generated an ortho-quinonemonoketal intermediate, which then underwent cyclopropanation to afford 51-2. Treatment of this cyclopropane with TFA directly yielded the natural product imerubrine. Hydrolysis followed by thermal rearrangement of the same intermediate provided grandirubrine.

Scheme 51.

Banwell’s synthesis of imerubrine and grandirubrine

In addition to sulfoxide, sulfone was also used for the cyclopropanation and ring expansion sequence for the preparation of tropones from quinonemonoketal derivatives.193

3.3.6 Formation of alkylidene cyclopropanes followed by ring expansion

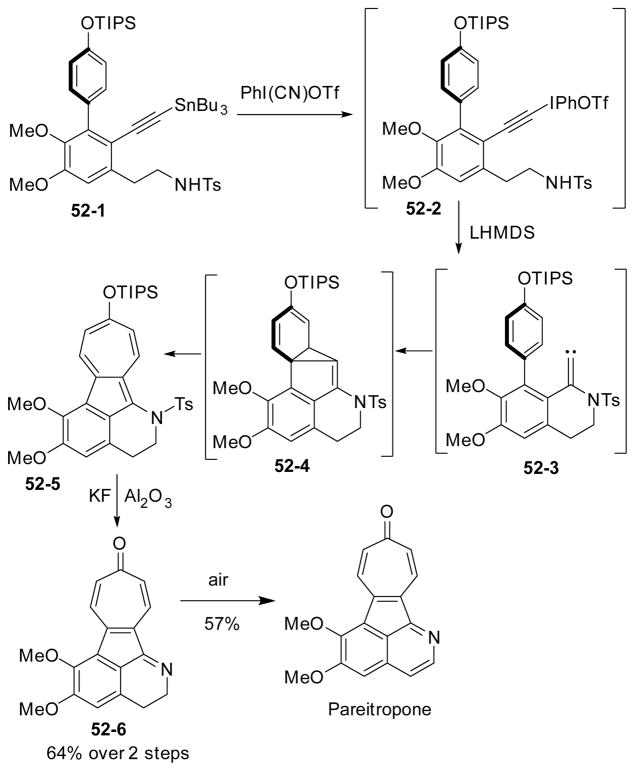

Alkynyliodonium salts are useful reagents in organic synthesis because they can be easily converted to alkylidene carbenes under mild conditions. Feldman’s group found that alkylidene carbenes could cyclopropanate arenes to form an alkylidene intermediate.194 In 2002, Feldman successfully prepared tropoloisoquinoline alkaloid pareitropone by ring expansion of alkylidene cyclopropanes (Scheme 52).195–196 Treatment of alkynylstannane 52-1 with Stang’s reagent followed by base afforded alkylidiene intermediate 52-3, which could react with the adjacent arene via a cyclopropanation and ring expansion cascade to afford cycloheptatriene 52-5. Removal of the to syl and TIPS groups followed by oxidation provided natural product pareitropone.

Scheme 52.

Feldman’s synthesis of pareitropone via ring expansion of alkylidene cyclopropane

3.3.7 Ring expansion of six-membered ring via Tiffeneau-Demjanov rearrangement

In Yoshikoshi’s synthesis of β-thujaplicin, the seven-membered cycloheptanone ring was derived from Tiffeneau-Demjanov ring expansion of cyclohexanone through a cyanohydrin intermediate (Scheme 53).197 The β-isopropyl substituted cycloheptanone 53-2A was then oxidized to the corresponding dione by SeO2. The target was completed by further bromination and elimination.

Scheme 53.

Ring expansion followed by oxidation of cycloheptanone to tropone

3.3.8 Ring expansion of three-membered ring

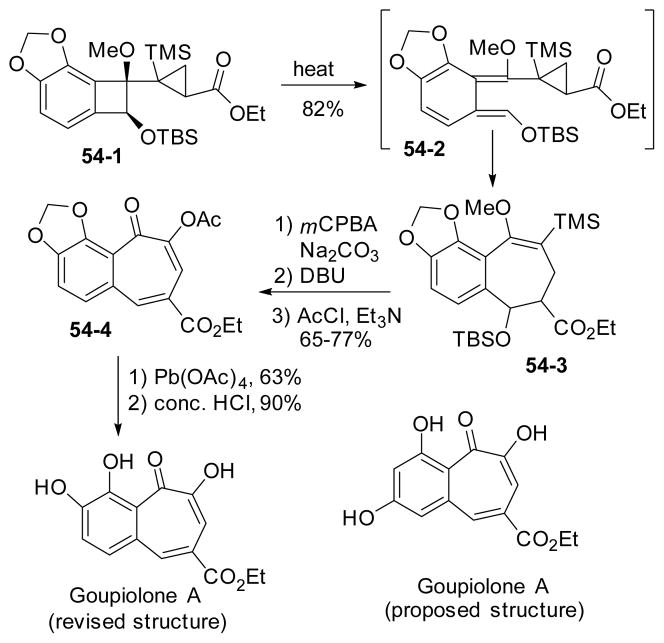

Recently, a synthesis of benzotropolone goupiolone A was reported featuring a ring expansion of cyclopropyl benzocyclobutene (Scheme 54).198–199 The cyclopropyl benzocyclobutene precursor 54-1 was prepared following protocols developed previously.198 The key ring expansion step was operated under thermal conditions to give a mixture of two diastereoisomers 54-3. Oxidation of the benzocycloheptene with mCPBA followed by hydrolysis and elimination gave tropolone 54-4 as the product. Finally the methylene acetal-protecting group was removed and the synthesis of goupiolone A was completed. The structure of this natural product was also revised based on synthesis.

Scheme 54.

Synthesis of goupiolone A via ring expansion of cyclopropyl-benzocyclobutenes and structural revision

3.4 Formation of the seven-membered ring by [5+2] cycloaddition

The [5+2] cycloaddition has been widely used in 7-membered ring synthesis. Some of them have also been applied to the synthesis of tropones and tropolones. Based on the reactive intermediates, four types of [5+2] cycloadditions are discussed below.

3.4.1 Perezone type [5+2] cycloaddition

The transformation of perezone to pipitzol was first discovered by Anschutz and Leather in 1885 (Scheme 55).200 The structure of pipitzol was later revised to a 7-membered ring with a carbonyl bridge and the mechanism of this type of [5+2] cycloaddition was studied in detail.201–207

Scheme 55.

Transformation of perezone to pipitzol

Buchi’s group applied this strategy to the synthesis of tropolones via a Lewis acid catalyzed [5+2] cycloaddition of quinonemonoketal and isosafrole (Scheme 56).208 The bicyclic compound 56-3 was converted to 4-aryltropolone methyl ether 56-4 through excursion of the carbonyl bridge followed by oxidation and hydrolysis.

Scheme 56.

Synthesis of substituted tropolones via perezone type [5+2] cycloaddition

3.4.2 Oxidopyrylium type [5+2] cycloaddition

Oxidopyrylium ions can undergo cycloadditions with unsaturated C-C bonds.209 The oxidopyrylium species can be generated by elimination of 2-acetoxypyran-5-one under basic condition210–213 or through group transfer of β-hydroxy-γ-pyrones under thermal condition.214 The resulting oxidopyrylium species could undergo intra- or intermolecular cycloadditions to afford oxa-bridged molecules, which then could be derivatized to tropones and tropolones.

In 2002, Baldwin and his co-workers reported a synthesis of deoxyepolone B by employing an intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of oxidopyrylium ion with an activated alkene (Scheme 57).215–216 An oxidative furan ring expansion followed by acylation gave the oxidopyrylium precursor 57-2, which underwent [5+2] cycloaddition with α-acetoxyacrylonitrile to yield seven-membered ring 57-4 with an oxygen bridge. It took over ten steps to convert this cycloaddition product to substituted tropolone 57-6 via intermediate 57-5. Deoxyepolone B was obtained by a biomimetic hetero-Diels-Alder cycloaddition of intermediate 57-7 with humulene.

Scheme 57.

Biomimetic synthesis of (±)-deoxyepolone B

In 2005, Celanire reported their synthetic progress towards cordytropolone via an intramolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of oxidopyrylium ion with an alkyne (Scheme 58).217 The 2,5-disubstituted furan 58-1 could be converted to 2-acetoxypyran-5-one 58-2 via oxidative rearrangement followed by acylation. A base-promoted intramolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of the resulting oxidopyrylium 58-3 with alkyne afforded intermediate 58-4 with an oxygen bridge.

Scheme 58.

Synthetic effort towards cordytropolone

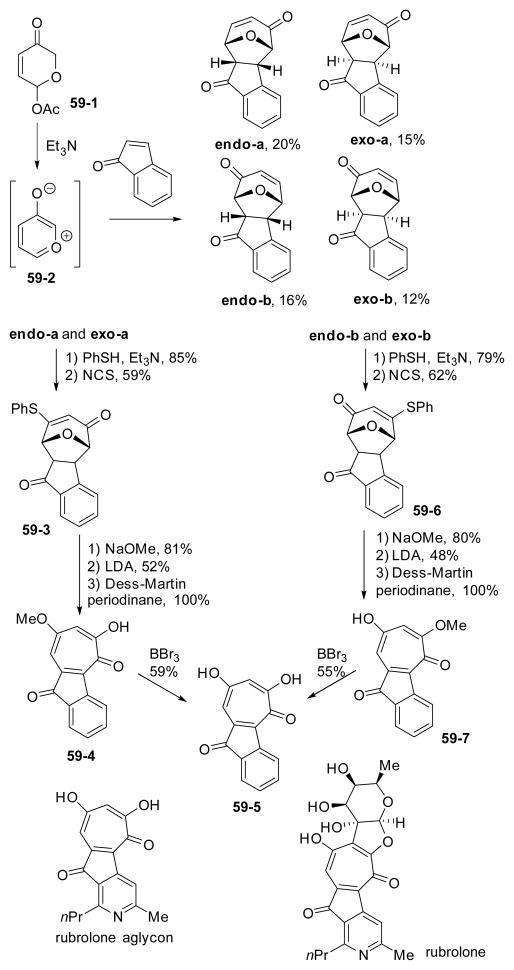

In 2010, Tchabanenko’s group reported a synthesis of the tropolone subunit in a model system for rubrolone aglycon (Scheme 59).218 The intermolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of oxidopyrylium ion 59-2 with indenone occurred non-selectively to afford four isomers. All four isomers could be converted to the same tropolone 59-5 reported by Boger in 1994219 after a series of identical manipulations including conjugate addition of thiophenol, Pummerer rearrangement mediated by NCS, substitution of the thiophenyl group by methoxy group, base-mediated elimination of the oxygen bridge, oxidation and BBr3-mediated cleavage of methyl ether.

Scheme 59.

Synthesis of tropolone subunit in a model compound for rubroloneaglycon via cycloaddition of oxidopyrylium ion

In 2013, Tang’s group reported the first total synthesis of harringtonolide,220 a naturally occurring tropone with significant anticancer activity. Highly substituted bicyclic decalin derivative 60-3 was converted to pentacyclic intermediate 60-5 via an intramolecular [5+2] cycloaddition of oxidopyrylium ion 60-4 and alkene (Scheme 60). After some functional group manipulations, the cycloheptadiene in 60-6 underwent a [4+2] cycloaddition with singlet oxygen. DBU-mediated Kornblum-DeLaMare rearrangement113 and elimination under acidic conditions yielded natural product hainanolidol with the tropone moiety. Treatment of hainanolidol with lead tetraacetate following literature conditions221 finally provided harringtonolide for the first time by total synthesis. All synthetic efforts towards harringtonolide or its related compounds from other groups29,222–225 did not yield the tropone moiety except the previously discussed synthesis from Mander in Scheme 35.

Scheme 60.

Total synthesis of (±)-harringtonolide

Tang’s group also reported an efficient way to convert known [5+2] cycloaddition product 61-1226 to tropone 61-5 in a model system of harringtonolide (Scheme 61).220 After the introduction of allylic thioether to 61-2 by a sequence of addition of methyl Grignard reagent and SN1′ displacement by thiophenol, a base-mediated anionic opening of the ether bridge occurred to yield bicyclic product 61-3. A sequence of hetero-Diels-Alder cycloaddition of cycloheptadiene with 2-nitrosopyridine,227 reductive cleavage of the N-O bond to an amino alcohol and double elimination in the presence of SnCl2 provided the tropone product 61-5 smoothly. Unfortunately, when this method was applied to the synthesis of harringtonolide, no desired hetero-Diels-Alder cycloaddition product was observed.

Scheme 61.

Synthesis of tropone from [5+2] cycloaddition product in a model system for (±)-harringtonolide

Many tropolones, such as β-thujaplicinol, puberulic acid and puberulonic acid, have two or more hydroxy groups on the seven-membered ring. Murelli’s group recently reported a general protocol for the synthesis of hydroxytropolones from kojic acid via [5+2] cycloaddition of oxidopyrylium followed by BCl3-mediated ring-opening of the ether bridge (Scheme 62).228 Changing the Lewis acid to triflic acid led to the formation of methoxytropolones.229

Scheme 62.

Synthesis of hydroxytropolones

3.4.3 [5+2] Cycloaddition through 3-hydroxypyridinium betaines

Katritzky and his co-workers first developed the synthesis of tropones by cycloaddition of 3-hydroxypyridinium betaines with alkenes or alkynes.230–233 Tamura applied this strategy to the synthesis of stipitatic acid and β-thujaplicin (Scheme 63).234 The 1,3-dipolar [5+2] cycloaddition of 3-hydroxypyridinium betaine 63-2 with ethyl propiolate gave the N-bridged compound 63-3, which underwent sequential alkylation and Hoffman elimination to afford the tropolone core in 63-5. Further hydrolysis by acid and base provided stipitatic acid. Tropolone β-thujaplicin was prepared similarly. A copper chromite mediated decarboxylation at high temperature was required in late stage synthesis.

Scheme 63.

Synthesis of stipitatic acid and β-thujaplicin via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition

3.5 Formation of the seven-membered ring by rhodium catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition of carbonyl ylide

When a carbonyl ylide is constrained in a six-membered ring, a [3+2] cycloaddition can lead to the formation of seven-membered rings. In 1992, Friedrichsen reported a synthesis of benzotropolones via [3+2] cycloaddition of a carbonyl ylide with alkyne (Scheme 64).235 In the presence of rhodium acetate, carbonyl ylide 64-2 was formed and it underwent an intramolecular [3+2] cycloaddition with the terminal alkyne to generate oxa-bridged compound 64-3, which was easily isomerized to the corresponding benzotropolone 64-4 by treatment with Lewis acid. They also applied the same strategy to the synthesis of hetero-annulated tropolones.236

Scheme 64.

Synthesis of benzotropolones through Rh (II) catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition

Baldwin’s group applied the rhodium-catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition of carbonyl ylide with alkyne to the synthesis of the tropolone core in epolone B (Scheme 65).237 Treatment of α-diazoketone 65-1 with rhodium acetate afforded tetracyclic product 65-3 via [3+2] cycloaddition. Exposure of this product to hydrochloric acid led to the cleavage of the ether bridge and the formation of tropolone 65-4, which underwent further transformations to yield an epolone B analogue.

Scheme 65.

Biomimetic synthesis of (±)-epolone B analogue

Schmalz successfully applied the Rh(II)-catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddition of carbonyl ylide and alkyne to the synthesis of colchicine (Scheme 66).238–239 Treatment of α-diazoketone 66-1 with rhodium acetate led to the formation of carbonyl ylide 66-2, which underwent an intramolecular [3+2] cycloaddition with the terminal alkyne to generate the oxa-bridged compound 66-3. Direct treatment of this compound with Lewis acid led to the formation of tropone 66-4, which could undergo non-selective α-functionalization to generate two aminotropones 66-5A/B. Reduction of the ketone in 66-3 by L-Selectride followed by TMSOTf mediated rearrangement and oxidation of the resulting diol could provide α-tropolone 66-6 selectively. The synthesis of colchicine was completed by further functionalization of this tropolone intermediate following previously established procedures.

Scheme 66.

Schmalz’s synthesis of (−)-colchicines via Rh-catalyzed carbonyl ylide cycloaddition

3.6 Formation of the seven-membered ring by [4+3] cycloaddition

3.6.1 Oxyallylcation [4+3] cycloaddition

Noyori’s group reported the synthesis of nezukone and β-thujaplicin in 1975 and 1978, respectively.240–241 The synthesis of the latter is shown in Scheme 67. An iron-promoted oxyallylcation [4+3] cycloaddition between tetrabromoketone 67-1 and 2-iso-propyl furan 67-3 provided the seven-membered ring in 67-4 with an oxygen bridge. The resulting bicyclic ketone underwent sequential hydrogenation and an acid-promoted elimination to yield a mixture of enone and dienone (67-5A/B), both of which could be converted to tropone 67-6. Treatment of the resulting tropone with hydrazine yielded the corresponding aminotropone 67-7, which was converted to the β-thujaplicin by exposure to KOH.

Scheme 67.

Noyori’s synthesis of β-thujaplicin via oxyallylcation [4+3] cyclization

The oxyallylcation species (e.g. 68-2) could also be generated through base-promoted elimination of α-haloketones (e.g. 68-1).242–246 This method was applied to the synthesis of substituted tropones after dehalogenation of the cycloaddition product followed by rearrangement (Scheme 68).247

Scheme 68.

Preparation of 3-methyl tropone via oxyallylcation [4+3] cycloaddition

Cha also applied the above method to the synthesis of tropolone thujaplicin by starting with 1,1,3-trichloroacetone and furan.248

The oxyallylcation can also be derived from silyl enol ether in the presence of Lewis acid (69-1 to 69-2, Scheme 69).249 Cha applied this method to the synthesis of colchicine250–251 and tropoloisoquinolines.252 The key [4+3] cycloaddition between substituted furan 69-3 and silyl enol ether 69-1 was carried out in the presence of TMSOTf. Only one diastereomer (69-4) was observed with the desired regioselectivity. Cleavage of the ether bridge253 followed by removal of the Boc group and acetylation afforded (−)-colchicine. Interestingly, in the presence of acetylamide in 69-6, the [4+3] cycloaddition yielded an isomer with undesired regioselectivity. The difference was rationalized by hydrogen bonding between the acetylamide and the methoxy group in oxyallylcation.

Scheme 69.

Cha’s synthesis of (−)-colchicine via oxyallylcation [4+3] cycloaddition

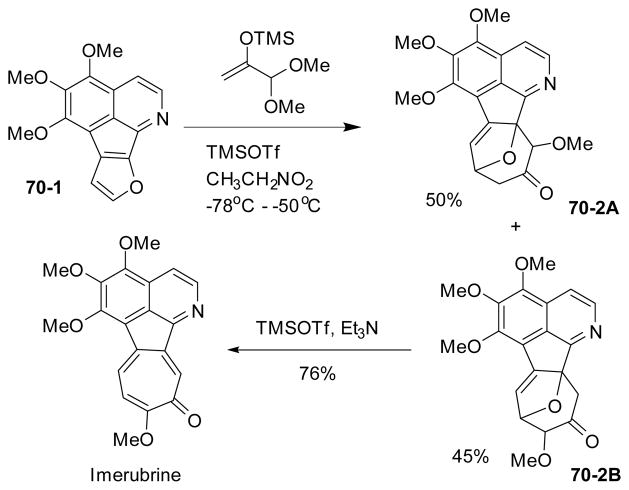

The same strategy was also employed in Cha’s synthesis of imerubrine (Scheme 70). The key [4+3] cycloaddition occurred under the same reaction conditions. In this case, the regioselectivity was low and a mixture of desired product 70-2B and its isomer 70-2A was observed in nearly a 1:1 ratio. Cleavage of the ether bridge in the desired isomer 70-2B and elimination of water then yielded imerubrine.

Scheme 70.

Synthesis of imerubrine via oxyallylcation [4+3] cycloaddition

3.6.2 Rh-catalyzed [4+3] cycloaddition via tandem cyclopropanation/Cope rearrangement

Davies’ group developed a Rh-catalyzed [4+3] cycloaddition of vinylcarbenoids with 1,3-dienes for the synthesis of highly functionalized cycloheptadienes,254–258 which could be converted to various substituted tropones and tropolones.259–260 The cascade reaction involved cyclopropanation of the metal carbenoid derived from diazo compound 71-1 with the less hindered double bond of the diene 71-2 and Cope rearrangement. A very short synthesis of nezukone demonstrated the efficiency of this strategy (Scheme 71).259

Scheme 71.

Davies’s synthesis of nezukone

Prior to Davies’s work, Wenkert also prepared the seven-membered ring in nezukone using a sequence of stepwise cyclopropanation of diene with ethyl diazopyruvate 72-1, olefination and Cope rearrangement (Scheme 72).261 The resulting cycloheptadiene 72-3 was oxidized by air to form the hydroperoxide, which was reduced by Me2S. Jones oxidation then led to the formation of keto-ester product 72-4. A base mediated isomerization followed by in-situ protection of the ketone as anenolate and addition of MeLito the ester followed by elimination afforded nezukone.

Scheme 72.

Wenkert’s synthesis of nezukone via cyclopropanation and Cope rearrangement

Wenkert also applied the above method to a formal synthesis of colchicine (Scheme 73).147 The divinylcyclopropane starting material 73-1 in this synthesis was prepared by the same strategy employed in Scheme 72.

Scheme 73.

Wenkert’s formal synthesis of (±)-colchicine via cyclopropanation and Cope rearrangement

3.6.3 [4+3] Cycloaddition of cyclopropenone ketal with dienes

Boger’s group reported an elegant thermal cycloaddition of cyclopropenone ketals262 with alkenes and dienes in the 1980s.263–267 The cycloaddition with α-pyrone is particularly intriguing since it provides a way to access tropone- or tropolone-containing natural products, such as colchicine (Scheme 74).265 It was believed that the cyclopropenone ketal 74-1 was in equilibrium with the vinylcarbene species 74-2, which underwent [4+3] cycloaddition with α-pyrone 74-3 to afford intermediate 74-4 with a lactone bridge. Decarboxylation then led to the formation of cycloheptatriene or tropone products 74-5. The synthesis of natural product colchicine was accomplished by Starting with pyrone 74-6.

Scheme 74.

Boger’s formal synthesis of (±)-colchicines via cycloaddition of cyclopropenone ketal with α-pyrone

3.7 Formation of the seven-membered ring by other cycloadditions

3.7.1 [2+2] Cycloaddition followed by fragmentation

A [2+2] cycloaddition between dihaloketene 75-2 and cyclopentadiene 75-1 could generate four-five fused bicyclic compound 75-3. Stevens and his coworkers applied this method to the synthesis of tropolone (Scheme 75).268 In the presence of sodium acetate in acetic acid, the four-five fused bicyclic compound could undergo enolization, addition/elimination, and fragmentation to form tropolone 75-4.269 This method was later applied to the total synthesis of various tropolones,269–271 such as β-thujaplicin, by starting with isopropyl substituted cyclopentadiene272 and a synthetic intermediate for colchicine (75-7) as shown in Scheme 75.273

Scheme 75.

Synthesis of tropolone via [2+2] cycloaddition of cyclopentadiene with dihaloketene and its application in a formal synthesis of colchicine

A synthesis of 3-substituted tropones was also reported starting with a photolytic [2+2] cycloaddition of 4-acetoxy cyclopent-2-en-1-one 76-1 and alkynes (Scheme 76).274–276 The [2+2] photolytic cycloaddition gave a mixture of two constitutional isomers 76-2A/B. One of them (76-2B) underwent an oxa-di-π-methane photo-rearrangement to afford 76-3. When the resulting mixture was exposed to alumina, 3-substituted tropone 76-6 was formed. When R is an isopropyl group, a synthesis of nezukone was realized.275

Scheme 76.

Synthesis of 3-substituted tropone (e.g. nezukone) under photolytic conditions

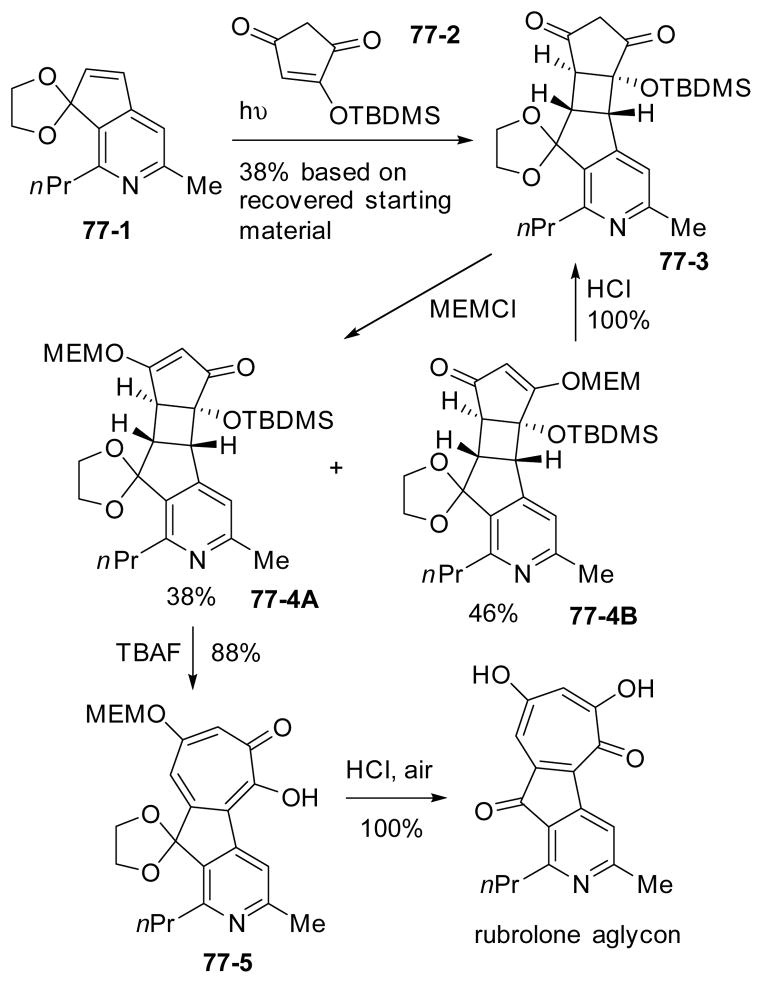

Kelly applied the [2+2] cycloaddition followed by fragmentation strategy to the first synthesis of rubroloneaglycon (Scheme 77).277 The photolytic [2+2] cycloaddition occurred regioselectively to give single adduct 77-3. Although only one isomeric MEM ether could undergo the retroaldol fragmentation to form the tropolone product 77-4A, the other MEM ether (77-4B) was recycled to diketone 77-3 after hydrolysis under acidic conditions.

Scheme 77.

Synthesis of rubroloneaglycon via [2+2] cycloaddition and fragmentation

3.7.2 [4+2] Cycloaddition followed by rearrangement

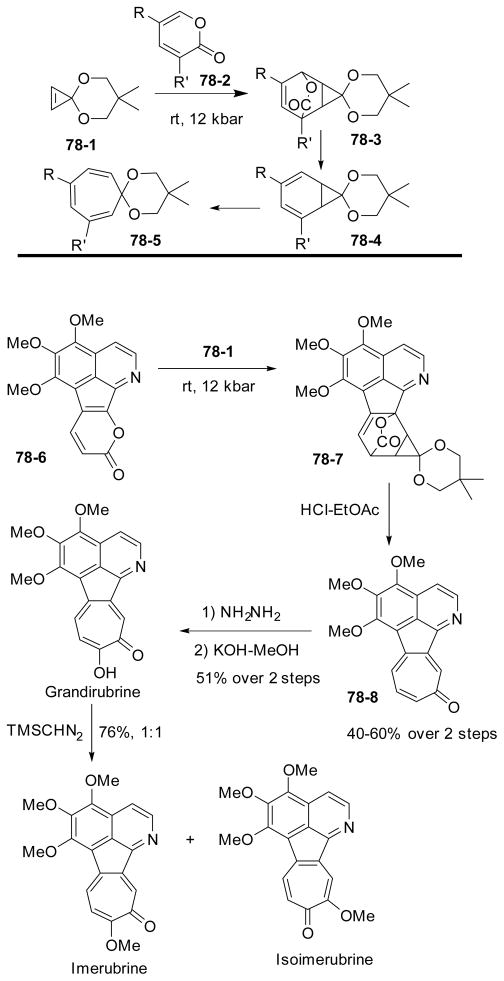

Boger reported the synthesis of tropones via a sequence of [4+3] cycloaddition of pyrone with cyclopropenone ketals followed by ring expansion and decarboxylation as discussed before. Interestingly, when the reaction was carried out at room temperature and under high pressure, a Diels-Alder [4+2] reaction occurred and the resulting adduct 78-3 was stable enough to be separated (Scheme 78).267 Decarboxylation followed by a ring expansion yielded tropone derivative 78-5 having the R and R’ groups at different positions on the ring. This method is complementary to the previous [4+3] cycloaddition for the synthesis of substituted tropones in Scheme 74. Boger’s group later reported the total synthesis of grandirubrine, imerubrine and isoimerubrine by applying the [4+2] cycloaddition of cyclopropenone ketal with α-pyrone 78-6.278 The Diels-Alder reaction occurred at room temperature and high pressure to afford tropone products after hydrolysis. Treatment of the resulting tropone 78-8 with hydrazine followed by hydrolysis completed the synthesis of grandirubrine, which could be converted to a mixture imerubrine and isoimerubrine after methylation.

Scheme 78.

Synthesis of grandirubrine and imerubrine via cycloaddition of cyclopropenone ketal and α-pyrone

Total synthesis of rubroloneaglycon was also realized by Boger’s group using a similar strategy (Scheme 79).219,279–280 The oxygenated tropolone in 79-4 was prepared by an exo-selective [4 + 2] cycloaddition of diene 79-1 and cyclopropenone ketal at room temperature followed by ring expansion of norcaradiene intermediate derived from 79-3.

Scheme 79.

Synthesis of rubroloneaglycon via cycloaddition of cyclopropenone ketal and ring expansion

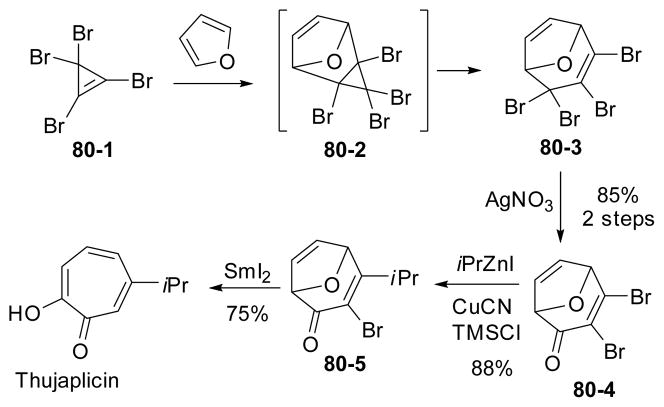

Recently, Wright’s group reported a synthesis of substituted tropolones involving a [4+2] cycloaddition of furans with tetrabromocyclopropene 80-1 (Scheme 80).281 This reaction was first discovered by Tobey and West in the 1960s282–283 and later investigated by Wright’s group for the synthesis of substituted cycloheptadienes.284–290 After the Diels-Alder cycloaddition, a sequence of rearrangement, hydrolysis in the presence of silver salts, addition of isopropyl zinc cuprate to enone and reduction by samarium diiodide yielded the tropolone natural product.

Scheme 80.

Synthesis of tropolones from cycloaddition of furan with TBCP and its application to the synthesis of thujaplicin

During the study of [4+2] Diels-Alder cycloaddition of o-benzoquinone 81-1 and aryl acetylene 81-2 for the synthesis of polysubstituted aromatic compounds, Nair’s group accidently found that under SnCl4 catalysis, the major product was tropone derivative 81-5 (Scheme 81).291

Scheme 81.

Synthesis of tropones via [4+2] cycloaddition followed by rearrangement

The o-benzoquinone underwent a Lewis acid catalyzed Diels- Alder cycloaddition with phenylacetylene to afford a bicycle [2.2.2] product. In the presence of SnCl4, this intermediatere arranged to [3.2.1] bicyclic product,292 which was converted to tropone after eliminating a carbon monoxide molecule.

4. Conclusion

It was a very exciting breakthrough when the structures of tropolone-containing natural products were first proposed by Dewar. Numerous synthetic efforts were reported on the synthesis and chemical reactivity of tropones and tropolones from 1950s to 1960s. During the last decades, attention was attracted to this family of compounds again because of newly isolated tropolone-containing natural products and their bioactivities. This review summarized methods developed for the synthesis of tropones and tropolones that were found in natural products based on how the seven-membered rings were constructed. It should facilitate the synthesis of tropolone-containing compounds discovered in nature or designed by medicinal chemists.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Wisconsin and NIH (R01GM088285) for funding.

Biographies

Na Liu received her B.S. degree in Chemistry from Peking University in 2008, where she conducted her undergraduate research in Professor Zhangjie Shi’s lab. She graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2013 with a Ph.D. degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences under the guidance of Professor Weiping Tang. She is currently a scientist at Elevance Renewable Sciences.

Na Liu received her B.S. degree in Chemistry from Peking University in 2008, where she conducted her undergraduate research in Professor Zhangjie Shi’s lab. She graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2013 with a Ph.D. degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences under the guidance of Professor Weiping Tang. She is currently a scientist at Elevance Renewable Sciences.

Wangze Song received his B.S. degree in Chemistry from Nankai University in 2008, where he began his undergraduate research in Professor Chi Zhang’s lab. He earned his M.S. degree in Chemistry from Zhejiang University in 2011 under the supervision of Professor Yanguang Wang and Professor Ping Lv. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. degree in Professor Weiping Tang’s lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Wangze Song received his B.S. degree in Chemistry from Nankai University in 2008, where he began his undergraduate research in Professor Chi Zhang’s lab. He earned his M.S. degree in Chemistry from Zhejiang University in 2011 under the supervision of Professor Yanguang Wang and Professor Ping Lv. He is currently pursuing his Ph.D. degree in Professor Weiping Tang’s lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Casi M. Schienebeck received her B.A. degree in chemistry from the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities in 2009 and worked in Professor Richard Hsung’s lab as an undergraduate researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She stayed at the same institute for her graduate studies under the supervision of Professor Weiping Tang.

Casi M. Schienebeck received her B.A. degree in chemistry from the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities in 2009 and worked in Professor Richard Hsung’s lab as an undergraduate researcher at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She stayed at the same institute for her graduate studies under the supervision of Professor Weiping Tang.

Min Zhang received his B.S. degree in Pharmacy and Ph.D. degree in Medicinal Chemistry from West China School of Pharmacy, Sichuan University in 2003 and 2009, respectively. During his graduate studies, he completed the total synthesis of natural products minfiensine and vincorine in Professor Yong Qin’s lab. He worked in Professor Weiping Tang’s lab as a postdoctoral fellow between 2009 and 2013 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he completed the total synthesis of tropone-containing natural products hainanolidol and harringtonolide. In 2013, Min Zhang joined the faculty of Innovative Drug Discovery Centre at Chongqing University as a professor. His group is interested in the development of novel efficient synthetic methods and strategies for total synthesis of bioactive natural products.

Min Zhang received his B.S. degree in Pharmacy and Ph.D. degree in Medicinal Chemistry from West China School of Pharmacy, Sichuan University in 2003 and 2009, respectively. During his graduate studies, he completed the total synthesis of natural products minfiensine and vincorine in Professor Yong Qin’s lab. He worked in Professor Weiping Tang’s lab as a postdoctoral fellow between 2009 and 2013 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he completed the total synthesis of tropone-containing natural products hainanolidol and harringtonolide. In 2013, Min Zhang joined the faculty of Innovative Drug Discovery Centre at Chongqing University as a professor. His group is interested in the development of novel efficient synthetic methods and strategies for total synthesis of bioactive natural products.

Weiping Tang received his B.S. degree from Peking University, M.S. degree from New York University and Ph.D. degree from Stanford University. He was a Howard Hughes Medical Institute postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University and Broad Institute. He is currently an associate professor in the School of Pharmacy and Department of Chemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His group is interested in developing new synthetic methods, total synthesis of natural products, medicinal chemistry and chemical biology.

Weiping Tang received his B.S. degree from Peking University, M.S. degree from New York University and Ph.D. degree from Stanford University. He was a Howard Hughes Medical Institute postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University and Broad Institute. He is currently an associate professor in the School of Pharmacy and Department of Chemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His group is interested in developing new synthetic methods, total synthesis of natural products, medicinal chemistry and chemical biology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Houk KN, Woodward RB. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:4145. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houk KN, Luskus LJ, Bhacca NS. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:6392. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noble WJL, Ojosipe BA. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:5939. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trost BM, Seoane PR. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:615. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machiguchi T, Hasegawa T, Ishii Y, Yamabe S, Minato T. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:11536. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair V, Poonoth M, Vellalath S, Suresh E, Thirumalai R. J Org Chem. 2006;71:8964. doi: 10.1021/jo0615706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trost BM, McDougall PJ, Hartmann O, Wathen PT. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14960. doi: 10.1021/ja806979b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16628. doi: 10.1021/ja908127f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie M, Liu X, Wu X, Cai Y, Lin L, Feng X. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:5604. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Wu Y, Zhao Y, Li Z, Zhang L, Yang W, Jiang H, Jing C, Yu H, Wang B, Xiao Y, Guo H. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:2625. doi: 10.1021/ja4122268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teng H-L, Yao L, Wang C-J. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:4075. doi: 10.1021/ja500878c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindberg GD, Larkin JM, Whaley HA. J Nat Prod. 1980;43:592. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azegami K, Nishiyama K, Kato H. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:844. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.3.844-847.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao J. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2597. doi: 10.2174/092986707782023253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bentley R. Nat Prod Rep. 2008;25:118. doi: 10.1039/b711474e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ononye SN, VanHeyst MD, Oblak EZ, Zhou W, Ammar M, Anderson AC, Wright DL. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:757. doi: 10.1021/ml400158k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day JA, Cohen SM. J Med Chem. 2013;56:7997. doi: 10.1021/jm401053m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dewar MJS. Nature. 1945;155:50. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dewar MJS. Nature. 1945;155:141. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erdtman H, Gripenberg J. Nature. 1948;161:719. doi: 10.1038/161719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erdtman H, Gripenberg J. Nature. 1949;164:316. doi: 10.1038/164316a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nozoe T. Sci Rep Tohoku Univ, Ser 1: Phys, Chem, Astron. 1950;34:199. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nozoe T. Nature. 1951;167:1055. doi: 10.1038/1671055a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pauson PL. Chem Rev. 1955;55:9. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pietra F. Chem Rev. 1973;73:293. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietra F. Acc Chem Res. 1979;12:132. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banwell MG. Aust J Chem. 1991;44:1. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graening T, Schmalz HG. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:3230. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdelkafi H, Nay B. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:845. doi: 10.1039/c2np20037f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meck C, D’Erasmo MP, Hirsch DR, Murelli RP. Med Chem Comm. 2014;5:842. doi: 10.1039/C4MD00055B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Banwell MG, Cowden CJ, Gravatt GL, Rickard CEF. Aust J Chem. 1993;46:1941. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirose Y, Tomita B, Nakatsuk T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1966:5875. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirose Y, Tomita B, Nakatsuk T. Agric Biol Chem. 1968;32:249. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polonsky J, Varenne J, Prange T, Pascard C, Jacquemin H, Fournet A. J Chem Soc-Chem Commun. 1981:731. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Geng H, Bruhn JB, Nielsen KF, Gram L, Belas R. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:1535. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02339-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greer EM, Aebisher D, Greer A, Bentley R. J Org Chem. 2008;73:280. doi: 10.1021/jo7018416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiel V, Brinkhoff T, Dickschat JS, Wickel S, Grunenberg J, Wagner-Doebler I, Simon M, Schulz S. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:234. doi: 10.1039/b909133e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seyedsayamdost MR, Case RJ, Kolter R, Clardy J. Nat Chem. 2011;3:331. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seyedsayamdost MR, Carr G, Kolter R, Clardy J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18343. doi: 10.1021/ja207172s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buta JG, Flippen JL, Lusby WR. J Org Chem. 1978;43:1002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun N-J, Xue Z, Liang X-T, Huang L. Acta pharm Sin. 1979;14:39. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang SQ, Cai SY, Teng L. Acta pharm Sin. 1981;16:867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evanno L, Jossang A, Nguyen-Pouplin J, Delaroche D, Herson P, Seuleiman M, Bodo B, Nay B. Planta Med. 2008;74:870. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1074546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Du J, Chiu MH, Nie RL. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:1664. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoon KD, Jeong DG, Hwang YH, Ryu JM, Kim J. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:2029. doi: 10.1021/np070327e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prasad K, Kapoor R, Lee P. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;139:27. doi: 10.1007/BF00944200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abou-Karam M, Shier WT. Phytother Res. 1999;13:337. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1573(199906)13:4<337::AID-PTR451>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu TW, Zeng LH, Wu J, Fung KP, Weisel RD, Hempel A, Camerman N. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1073. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00447-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farnet CM, Wang B, Hansen M, Lipford JR, Zalkow L, Robinson WE, Siegel J, Bushman F. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2245. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu TW, Wu J, Zeng LH, Au JX, Carey D, Fung KP. Life Sci. 1994;54:Pl23. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00784-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vermeer MA, Mulder TPJ, Molhuizen HOF. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:12031. doi: 10.1021/jf8022035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roberts RAC. J Sci Food Agric. 1957;8:72. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin JK. Arch Pharmacal Res. 2002;25:561. doi: 10.1007/BF02976924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukamal KJ, Maclure M, Muller JE, Sherwood JB, Mittleman MA. Circulation. 2002;105:2476. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017201.88994.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hakim IA, Alsaif MA, Alduwaihy M, Al-Rubeaan E, Al-Nuaim AR, Al-Attas OS. Prev Med. 2003;36:64. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacKenzie T, Comi R, Sluss P, Keisari R, Manwar S, Kim J, Larson R, Baron JA. Metabolism. 2007;56:1694. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Celik F, Celik M, Akpolat V. J Diabet Complications. 2009;23:304. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Silverton JV, Kabuto C, Buck KT, Cava MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:6708. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Menachery MD, Cava MP. Heterocycles. 1980;14:943. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morita H, Matsumoto K, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Iitaka Y. Chem Lett. 1993:339. doi: 10.1248/cpb.41.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morita H, Matsumoto K, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Iitaka Y. Chem Pharm Bull. 1993;41:1418. doi: 10.1248/cpb.41.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morita H, Matsumoto K, Takeya K, Itokawa H. Chem Pharm Bull. 1993;41:1478. doi: 10.1248/cpb.41.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morita H, Takeya K, Itokawa H. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1995;5:597. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Itokawa H, Matsumoto K, Morita H, Takeya K. Heterocycles. 1994;37:1025. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pelletier PJ, Caventou JB. Ann Chim Phys. 1820;14:69. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Geiger PL. Annalen der Pharmacie. 1833;7:269. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Altel TH, Abuzarga MH, Sabri SS, Freyer AJ, Shamma M. J Nat Prod. 1990;53:623. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cox RJ, Al-Fahad A. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2013;17:532. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Battersby AR, Dobson TA, Foulkes DM, Herbert RB. J Chem Soc Perkin 1. 1972;14:1730. doi: 10.1039/p19720001730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Battersby AR, Herbert RB, Pijewska L, Santavy F, Sedmera P. J Chem Soc Perkin 1. 1972;14:1736. doi: 10.1039/p19720001736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Battersby AR, Herbert RB, McDonald E, Ramage R, Clements JH. J Chem Soc Perkin 1. 1972;14:1741. doi: 10.1039/p19720001741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wightman RH, Staunton J, Battersby AR, Hanson KR. J Chem Soc Perkin 1. 1972;18:2355. doi: 10.1039/p19720002355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strange PG, Stauton J, Wiltshire HR, Battersby AR, Hanson KR, Havir EA. J Chem Soc Perkin 1. 1972;18:2364. doi: 10.1039/p19720002364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Battersby AR, Laing DG, Ramage R. J Chem Soc Perkin 1. 1972;21:2743. doi: 10.1039/p19720002743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tanaka T, Mine C, Inoue K, Matsuda M, Kouno I. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:2142. doi: 10.1021/jf011301a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanaka T, Kouno I. Food Sci Tech Res. 2003;9:128. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sang S, Lambert JD, Ho C-T, Yang CS. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:87. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yanase E, Sawaki K, Nakatsuka S. Synlett. 2005:2661. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Salfeld JC. Angew Chem. 1957;69:723. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Horner L, Dürckheimer W, Weber K-H, Dölling K. Chem Ber. 1964;97:312. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takino Y, Ferretti A, Flanagan V, Gianturc M, Vogel M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1965:4019. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kerschensteiner L, Loebermann F, Steglich W, Trauner D. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:1536. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kawabe Y, Aihara Y, Hirose Y, Sakurada A, Yoshida A, Inai M, Asakawa T, Hamashima Y, Kan T. Synlett. 2013;24:479. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sang SM, Lambert JD, Tian SY, Hong JL, Hou Z, Ryu JH, Stark RE, Rosen RT, Huang MT, Yang CS, Ho CT. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:459. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harmata M. Chem Commun. 2010;46:8886. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03620j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harmata M. Chem Commun. 2010;46:8904. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03621h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lohse AG, Hsung RP. Chem Eur J. 2011;17:3812. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pellissier H. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:189. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ylijoki KEO, Stryker JM. Chem Rev. 2013;113:2244. doi: 10.1021/cr300087g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Battiste MA, Pelphrey PM, Wright DL. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:3438. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Butenschön H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5287. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nguyen TV, Hartmann JM, Enders D. Synthesis. 2013;45:845. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cook JW. Chem Ind. 1950:427. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Knight JD, Cram DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:4136. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dauben HJ, Ringold HJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:876. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jones G. J Chem Soc C. 1970:1230. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Doering WVE, Knox L. J Am Chem Soc. 1950;72:2305. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Doering WVE, Knox L. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:828. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Doering WVE, Knox L. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:297. [Google Scholar]

- 100.ter Borg AP, van Helden R, Bickel AF, Renold W, Dreiding AS. Helv Chim Acta. 1960;43:457. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Garfunkel E, Reingold ID. J Org Chem. 1979;44:3725. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Reingold ID, Dinardo LJ. J Org Chem. 1982;47:3544. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shono T, Nozoe T, Maekawa H, Kashimura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:555. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shono T, Maekawa H, Nozoe T, Kashimura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:895. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shono T, Nozoe T, Maekawa H, Yamaguchi Y, Kanetaka S, Masuda H, Okada T, Kashimura S. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:593. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shono T, Okada T, Furuse T, Kashimura S, Nozoe T, Maekawa H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1992;33:4337. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Breton T, Liaigre D, Belgsir E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:2487. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dahnke KR, Paquette LA. Org Synth. 1993;71:181. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Balci M, Sutbeyaz Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:311. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Balci M, Sutbeyaz Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1983;24:4135. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sengul ME, Balci M. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1. 1997:2071. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sengul ME, Ceylan Z, Balci M. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:10401. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kornblum N, DeLaMare H. J Am Chem Soc. 1951;73:880. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Celik M, Akbulut N, Balci M. Helv Chim Acta. 2000;83:3131. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dastan A, Saracoglu N, Balci M. Eur J Org Chem. 2001:3519. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dastan A, Balci M. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:4003. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Coskun A, Guney M, Dastan A, Balci M. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4944. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Guney M, Dastan A, Balci M. Helv Chim Acta. 2005;88:830. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yamamoto K, Matsue Y, Murata I. Chem Lett. 1981:1071. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang X, Wang DY, Emge TJ, Goldman AS. Inorg Chim Acta. 2011;369:253. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Nicolaou KC, Zhong YL, Baran PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7596. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nicolaou KC, Montagnon T, Baran PS, Zhong YL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:2245. doi: 10.1021/ja012127+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Cui L-D, Dong Z-L, Liu K, Zhang C. Org Lett. 2011;13:6488. doi: 10.1021/ol202777h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Franckneumann M, Brion F, Martina D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;19:5033. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Seto S, Matsumura S, Ro K. Chem Pharm Bull. 1962;10:901. doi: 10.1248/cpb.10.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Scott AI, McCapra F, Buchanan RL, Day AC, Young DW. Tetrahedron. 1965;21:3605. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4020(01)96977-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kaneko SI, Matsui M. Agric Biol Chem. 1968;32:995. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sunagawa G, Nakamura T, Nakazawa J. Chem Pharm Bull. 1962;10:291. doi: 10.1248/cpb.10.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nakamura T. Chem Pharm Bull. 1962;10:299. doi: 10.1248/cpb.10.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Shono T, Nozoe T, Yamaguchi Y, Ishifune M, Sakaguchi M, Masuda H, Kashimura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:1051. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Saito T, Itoh A, Oshima K, Nozaki H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979:3519. [Google Scholar]

- 132.van Tamelen EE, Spencer TA, Allen DS, Orvis RL. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;81:6341. [Google Scholar]

- 133.van Tamelen EE, Spencer TA, Allen DS, Orvis RL. Tetrahedron. 1961;14:8. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Martel J, Toromano E, Huynh C. J Org Chem. 1965;30:1752. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Woodward RB. The Harvey Lecture Series. 1963;59:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Soung MG, Matsui M, Kitahara T. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:7741. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mori M, Inouye Y, Kakisawa H. Chem Lett. 1989:1021. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Haro G, Mori M, Ishitsuka MO, Kusumi T, Inouye Y, Kakisawa H. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1991;64:3422. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ginda H, Kusumi T, Ishitsuka MO, Kakisawa H, Weijie Z, Jur C, Tian GY. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988;29:4603. [Google Scholar]

- 140.Liang JY, Min ZD, Iinuma M, Tanaka T, Mizuno M. Chem Pharm Bull. 1987;35:2613. doi: 10.1248/cpb.35.2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Liang JY, Min ZD, Tanaka T, Mizuno M, Ilnuma M. Acta Chim Sinica. 1988;46:21. [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wang XC, Pan XF, Zhang C, Chen YZ. Synth Commun. 1995;25:3413. [Google Scholar]