Summary

Objectives

We surveyed the UK medical qualifiers of 1993. We asked closed questions about their careers; and invited them to give us comments, if they wished, about any aspect of their work. Our aim in this paper is to report on the topics that this senior cohort of UK-trained doctors who work in UK medicine raised with us.

Design

Questionnaire survey

Participants

3479 contactable UK-trained medical graduates of 1993.

Setting

UK.

Main outcome measures

Comments made by doctors about their work, and their views about medical careers and training in the UK.

Method

Postal and email questionnaires.

Results

Response rate was 72% (2507); 2252 were working in UK medicine, 816 (36%) of whom provided comments. Positive comments outweighed negative in the areas of their own job satisfaction and satisfaction with their training. However, 23% of doctors who commented expressed dissatisfaction with aspects of junior doctors’ training, the impact of working time regulations, and with the requirement for doctors to make earlier career decisions than in the past about their choice of specialty. Some doctors were concerned about government health service policy; others were dissatisfied with the availability of family-friendly/part-time work, and we are concerned about attitudes to gender and work-life balance.

Conclusions

Though satisfied with their own training and their current position, many senior doctors felt that changes to working hours and postgraduate training had reduced the level of experience gained by newer graduates. They were also concerned about government policy interventions.

Keywords: physicians, career choice, medical staff, attitude of health personnel

Introduction

The UK medical qualifiers of 1993 began their careers at a time of change to medical education, training and working conditions. They were restricted initially, in theory, to working no more than 72 h per week under the then UK government’s ‘New Deal’,1 although this was not fully implemented until the end of the decade. The Calman Report of 1993 led to changes in higher specialist training between 1995 and 1997 to make it more structured.2 Since then, further changes to specialist training affected the graduates of 1993, in their later stages of training, including the introduction of the European Working Time Directive (EWTD) and Regulation (EWTR) between 2004 and 2009;3 and in their subsequent roles as trainers and educators.

We surveyed the 1993 graduates in 2010/11; most were in senior positions in clinical practice in the UK. We asked about their jobs, career progression and future career intentions and invited them to comment on any aspect of their training or work.

Our aim in this paper is to report on the doctors’ spontaneous comments: information which the doctors themselves wanted to convey, about their own experiences and about working in medicine. To this end, we categorised the themes commonly raised; and we report on some of the comments that raise points that we think are worthy of consideration.

Methods

We used postal questionnaires with up to four reminders to non-respondents. Further details of the methodology are available elsewhere.4,5

Doctors were asked to describe their current employment situation as ‘working in UK medicine’, ‘working in medicine, outside the UK’, ‘working outside medicine’ or ‘not in paid employment’. We focus on the responses of doctors working in UK medicine. Our invitation to comment was ‘Please give us comments, if you wish, on any aspect of your training or work’.

We redacted comments to preserve anonymity. We developed a coding scheme covering the main themes and sub-themes raised in the comments. Two researchers independently coded the comments, resolving differences through discussion. Each comment was assigned up to four codes, and each code was further categorised by us as ‘positive’, ‘neutral/mixed’ or ‘negative’. Most quotes we present are characteristic of a commonly raised theme. We have occasionally included interesting or novel points infrequently made, in the belief that they raise points that are worthy of attention. All are quoted exactly as written by the doctor.

Quantitative data were analysed by cross-tabulation and χ2 statistics.

Results

Response

The response rate was 72.1% (Table 1; 2507/3479). Responding doctors had a median age of 40; 49.9% (1251 respondents) were female. Of 2491 giving their current employment situation, 2252 (90.4%) were working in UK medicine (Table 1). Of these 816 (36.2%) gave comments.

Table 1.

1993 UK medical graduates in 2010: survey response and current work.

| Group | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original cohort | 1954 | 1717 | 3671 |

| Declined | 21 | 9 | 30 |

| Deceased | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| Untraceable | 78 | 67 | 145 |

| Surveyed cohort | 1844 | 1634 | 3479 |

| Respondents | 1255 | 1251 | 2507 |

| Response rate | 68.1% | 76.6% | 72.1% |

| Respondents who gave details of their current work | 1243 | 1248 | 2491 |

| In UK medicine | 1130 | 1122 | 2252 (90.4%) |

| In medicine outside the UK | 97 | 74 | 171 (6.9%) |

| Not in paid employment | 8 | 36 | 44 (1.8%) |

| Working outside medicine | 8 | 16 | 24 (1.0%) |

Overview of results

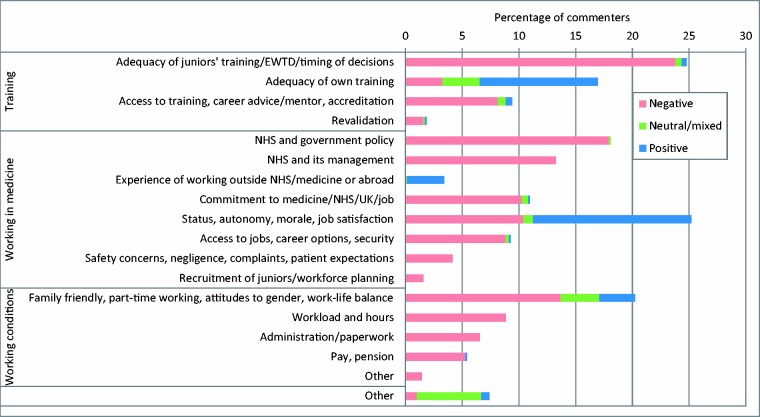

The 816 doctors who commented raised 1544 different comments classified by us to a theme (Appendix 1). Comments were made about working in medicine (481 doctors commented on this sub-theme), training in medicine (357) and working conditions (309).

Areas attracting the most positive comments were: ‘Status, autonomy, morale, job satisfaction’ (14.0% of those who gave comments), ‘Adequacy of own training’ (10.8%), ‘Experience of working outside NHS/medicine or abroad’ (3.9%) and ‘Family-friendly/part-time work, attitudes to gender, work-life balance’ (3.3%).

Areas drawing most criticism were ‘Adequacy of juniors’ training’ (23.2% of all doctors who commented gave negative comments on this; Figure 1, Appendix 1), ‘NHS and government policy’ (17.9%), ‘Family friendly/part-time work, attitudes to gender, work-life balance’ (13.4%), ‘NHS and its management’ (13.4 %) and ‘Commitment to medicine/NHS/UK/job’ (10.4%). Within ‘Adequacy of juniors’ training’ we included comments about the timing of juniors’ decisions about their specialty choices; the impact of EWTR on training; and the adequacy and quality of training.

Figure 1.

Comments made by senior doctors working in medicine in the UK.

Negative comments were analysed by gender: 20.9% of women and 4.1% of men made negative comments about lack of ‘Family-friendly/part-time work’, ‘attitudes to gender’, ‘work-life balance’ ( = 48.1, p < 0.001). ‘Adequacy of juniors’ training’ was raised more by men (32.2%) than women (15.8%; = 29.4, p < 0.001). ‘NHS and government policy’ ( = 8.5, p < 0.01), ‘NHS and its management’ ( = 6.7, p < 0.05) and ‘Pay, pension’ ( = 4.4, p < 0.05) were also raised more by men than women. Positive and negative comments were often juxtaposed (Box 1); but some positive comments were simply expressions of gratitude for having a career in medicine (e.g. ‘I absolutely love being a GP’).

Box 1. Examples of positive comments, with and without negative comments from the same doctors.

‘I love the clinical content of my job but feel increasing pressure to do more and more in limited time’ (female, genetics).

‘After 16 years I still love clinical medicine & really enjoy the relationships I have with my patients. It’s a challenging job & I’m never bored. I do find the volume of work hard’ (female, GP).

‘I thoroughly enjoy and value my career in medicine. There are considerable political and financial pressures that are making the provision of safe/quality care in healthcare more and more difficult to provide’ (male, anaesthetics).

‘(Medicine) is a potentially wonderful career currently being destroyed by political micro-management’ (female, GP).

‘Still enjoy medicine…GP constantly under fire from Government – demoralising & feel unappreciated’ (male, GP).

‘Love my job! I chose to be a GP right from day 1, as a house officer in hospital medicine. I took a GP vocational training scheme at the earliest opportunity & have been a principal in the same practice for 13 years. I am now senior partner’ (female, GP).

‘I love my job – I have great colleagues and a lot of satisfaction’ (male, anaesthetics).

‘I feel well trained and privileged to do the job I do’ (male, chest medicine).

‘I absolutely love being a GP. I live & work in the same community & I feel it’s such a privilege to have the job I have’ (female, GP).

‘I have really enjoyed my career and feel really lucky to be able to work and bring up my children’ (female, GP).

Training

(a) Views about the training of today’s junior doctors

Many doctors mentioned adverse effects of shortened training hours for juniors: a female GP principal wrote ‘…because of their reduced hours they [trainees] do not have the diagnostic or therapeutic confidence that was expected during my training’. A male trauma and orthopaedics consultant described ‘junior doctors with a reversed sense of work/life balance who are unable to take responsibility for their own learning’. Some respondents wrote that, as a consequence of shortened hours for juniors, they were working longer hours at higher intensity than in the past. A typical comment (female, consultant in clinical oncology) was ‘I provide a much greater consultant-led service than the consultants whom I worked for as an SpR [specialist registrar]’. Another consultant (male, hospital medicine) commented that the EWTD was responsible for his ‘increasing responsibility for work previously carried out by junior doctors’. Some seniors criticised junior colleagues. A female paediatrician wrote that they ‘read less’, ‘study very little’, ‘have far less responsibility’ and are ‘less competent’. A female anaesthetics consultant bemoaned juniors ‘…lacking experience, clock watchers, lack initiative, don’t take responsibility’. Some felt training had improved. A female GP principal wrote ‘we are training students now in a more encouraging way’. A female geriatrician wrote that ‘the current system has many advantages… there’s much more support and early recognition of struggling trainees, opportunities for trainees to explore career choices and a more consistent method of assessment’. Some, like this female geriatrician, contrasted training and experience: ‘We rush through training to produce senior doctors who have had lots of structured training (very laudable) but little experience’. Another female geriatrician thought her ‘own SpR training, although adequate, was not in any way as well structured as today’s training’. There was concern that junior doctors felt pressure to choose a specialty too soon after graduation. A male maxillofacial surgeon wrote that ‘the system stifles flexibility and shoe-horns trainees into specialties too early’; a male radiologist commented that ‘time spent as an SHO [senior house officer] allowed me to identify the ideal career choice of specialty’.

(b) Views of the doctors about their own training

Most respondents were positive about their own training, and many felt privileged to have had good training and good opportunities. A female emergency medicine consultant wrote: ‘I feel lucky to have had good training and good exposure to clinical medicine as a junior doctor’. Some doctors were less happy about their own training, describing it as ‘negligent’, ‘ad hoc’ or ‘lacking structure or support from seniors’. Several doctors spoke of being bullied when they were in training: a male consultant in orthopaedics wrote that training was ‘poor in general and mainly done through humiliation and bullying’, and a female surgeon described her postgraduate training as ‘very demoralising – lots of being told off’.

(c) Views of senior doctors about further training, career advice, mentoring and revalidation

Concerns about professional advancement, mentoring and future changes were widely expressed. A female GP principal wrote ‘…partners cannot afford time nor finances away from practice to train’, and a salaried female GP wrote that she had ‘no scope for career advancement or professional development’. Some doctors, for example those with portfolio careers or in unrecognised specialties such as obesity management, were concerned that their career might not fit revalidation criteria. Others wrote that revalidation was too time consuming ‘When do I do all this reflection, audit… weekends or evenings?… I don’t want to do this stuff’ (a female GP principal).

Working in medicine

(a) Views about the NHS and government policy, and the NHS and its management

There was dissatisfaction with government NHS policy (as it was in 2010), criticising ‘frequent change’ and a ‘target-driven culture’. A male ophthalmology consultant wrote that ‘NHS targets, financial pressures have made working in the NHS increasingly less fulfilling’, and a male GP principal wrote that ‘too many significant changes are made to the NHS by politicians… without thinking about the consequences’. Some doctors thought that NHS managers ‘have inadequate experience to manage’ (a male rheumatology consultant) and that too much time was ‘spent [by doctors] in useless meetings with mediocre managers’ (female consultant in obstetrics and gynaecology). A male chest medicine consultant wrote of ‘consultants mistreated and bullied by managers with little knowledge of clinical issues’. A male paediatrician facing a major management re-organisation wrote ‘I will, as with every other re-organisation, feign delight and commitment, flexibility and engagement, excitement and re-energisation while inside a little bit more of my vocation to heal withers and dies’. Just over half of doctors who made comments related to ‘status, autonomy, morale and job satisfaction’ were positive, with many doctors saying how much they had enjoyed their career so far (Box 1). Some doctors wrote about loss of morale and of autonomy. A female consultant in geriatric medicine wrote about ‘the inflexibility of colleagues, management, lack of support for consultants new in post and ever decreasing numbers of doctors to work with… I was once inspired, now I am just cynical’. A female radiology consultant felt ‘less valued than clerical staff’, and a female rheumatology consultant wrote of ‘loss of autonomy and professionalism’.

(b) Views and experience of working outside the UK and the NHS

Dissatisfaction led some to question their commitment to the NHS and the UK. One female paediatrician wrote that she hoped to ‘leave the UK to work in Australia. The NHS (of which I was a staunch supporter) is not a place in which I wish to practice medicine. Doctors are no longer empowered or enabled to give the care they want to give within the constraints imposed’. Doctors relayed positive experiences of working outside the UK. A female GP principal wrote ‘medicine has been a fantastic vehicle with which to travel and explore the world’. A male GP principal described 18 months in New Zealand as ‘a fantastic experience & educationally very useful’.

(c) Access to jobs, career opportunities and part-time working

Some doctors described limited career options. A female GP felt ‘slightly less valued [as a] member of the team’ following maternity leave and part-time working. A male part-time paediatrician wrote that there was ‘still a barrier to be overcome regarding working less than full-time’.

(d) Safety concerns, negligence, complaints and patients’ expectations

A male anaesthetics consultant thought political and financial pressures were ‘making the provision of safe/quality care in healthcare more and more difficult’. Alongside safety concerns, some doctors perceived a reluctance to address shortcomings. One woman consultant pathologist wrote ‘… raising concerns does not work effectively within my Trust & appears to result in “scapegoating the whistleblower”’. Many doctors felt patients’ expectations were too high – ‘the NHS will be unsustainable in its current form’ wrote one female GP, who saw ‘more and more demanding patients for minor self-limiting illnesses’. Negligence claims worried some: ‘trying to do a day’s work is now clouded by constant fears of unfounded complaints from patients and threats of litigation’ (female, GP). Trainee shortages were mentioned by a male geriatrician who wrote that ‘medicine is under enormous pressure at present, with major gaps at junior doctor level’, and a paediatric consultant expressed concern over ‘the current shortage of trainees entering paediatric training’.

Working conditions

(a) Family-friendly/part-time work, attitudes to gender and work-life balance

Some women doctors wrote to us that they had received inadequate support from their employer during pregnancy and thereafter, and found it difficult to get part-time work. Some, like this female anaesthetist, ‘longed to be part-time’ but ‘I was full-time because I had no option.… [I was given] little or no support from the NHS’. A female psychiatry consultant had ‘come across discrimination [in named deanery] due to childcare choices and opportunities’, and a third, a female consultant in ophthalmology, after returning to work part-time, felt ‘a slightly less valued member of the team and more vulnerable to job cuts’. A female clinical academic wrote that she changed career because of ‘sex discrimination and often a bullying culture’, and a female consultant psychiatrist described ‘having to delay my family. This should not still be happening but attitudes (in male and female colleagues) have been slow to change’. Some men also reported problems in maintaining a good work-life balance. Comments included ‘excessive workload/poor work-life/balance remains an on-going problem’ (consultant psychiatrist) and ‘too busy to enjoy own life to the full… no proper holiday in 7 years now… work/life balance still leaves a lot to be desired’ (consultant ophthalmologist). However, some doctors, most commonly GPs, but also notably radiologists and public health doctors, wrote that they had a good work-life balance: ‘I feel very lucky to have been able to have three children, work flexibly and achieve my CCST [Certificate of Completion of Specialist Training] in public health’.

(b) Workload and hours

Some doctors wrote about intensive workload and long hours. A female GP principal wrote ‘I cannot physically work any harder in a session than I do at the moment. If the current trend… continues I will leave medicine’.

(c) Administration/paperwork

There were adverse comments about demands of administration and bureaucracy. A salaried female GP wrote ‘I work part-time as a GP as I find the job stressful. I find myself with lots of paperwork which takes me beyond my contracted hours’; a male GP principal wrote that there was ‘too much bureaucracy, admin and reports to complete for the PCT [Primary Care Trust]’ and wrote comments about the ‘constant barrage of red tape, box ticking exercises and bureaucracy’.

Discussion

Main findings

The adequacy (or lack of it) of junior doctors’ training was the respondents’ main concern, particularly with regard to the impact of the implementation of the EWTR (on which we have published in detail elsewhere6,7), which they felt had, in many cases, reduced the hours junior doctors spent in training and lengthened the hours of senior doctors. They also felt that junior doctors may now have to choose their specialty too early. Other areas of concern were NHS management and the availability of family-friendly and part-time work.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Frequency counts provided an indication of the relative importance of different issues that the doctors wanted to raise with us. Over 800 doctors made comments and the data represent the spontaneously expressed views of almost a quarter of all doctors in the qualifying cohort. However, doctors who comment may well have different views from those who do not.8 As with all invitations for comment it is possible that those with mainly negative views, or with particularly strongly held views, are more inclined to provide comments.9 The value of the comments lies mainly in gaining information about the kinds of concerns doctors wanted to express when they decided that they wanted to comment.

Comparison with existing literature

Our respondents were dissatisfied with the adequacy of junior doctors’ training, and many referred to impact of the EWTD upon this and upon the intensity of their own work. A recent review of the impact of the Working Time Regulations found that trainee doctors consider the 48 h week to be appropriate yet inflexible, and that they still worked long hours at high intensity.10 Some concerns about the adequacy of training are not new; a study in 2002, of these same qualifiers of 1993, found that some had experienced difficulty accessing training in their chosen career, felt that training was inadequate, and anticipated a shortage of consultant vacancies.8

Similar views were held by other senior doctors. A national survey of British GPs in 2011 found that GPs were dissatisfied with time for continuing professional development, with their workload and with NHS management.11 A survey of medical registrars in England found a reluctance to work over 48 h a week, even if paid more; these doctors were also worried about their future job prospects, and 40% were ‘not looking forward’ to becoming a consultant.12

Some doctors in our study found it difficult to access part-time work and felt they were treated differently when they chose to work part-time or when they had children. Another study found that less than full-time (LTFT) trainees were often less integrated into their teams and felt more remote than full-time (FT) trainees in UK general practice.13 Interviews with UK hospital consultants revealed a resistance, generally, to flexible working and part-time work.14 The authors point out that, because most part-time doctors are women, they are affected more than men. Other studies have found that gender and parenthood impact negatively on female doctors’ careers and lives.15,16

Implications

Concerns about the adequacy of training opportunities for the current generation of junior doctors need to be addressed, as do concerns that some junior doctors have to make their career choice of future specialty too soon. This confirms the value of current initiatives to extend opportunities for skills transferability and deferred decision-making for doctors unable to make an early choice, while maintaining the option to begin specialist training early for those who are sure of their choices. Some seniors were concerned about their own continuing professional development and a lack of opportunities to pursue further training. Work-life balance remains an important issue and it is a policy area in which further measures were felt by some to be desirable.

Appendix 1. Frequency distribution of commentsa provided by senior doctors working in medicine in the UK (N = 816)

| Theme | Negative | Neutral/mixed | Positive | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | ||||

| Adequacy of juniors’ training | 189 | 4 | 4 | 197 |

| Adequacy of own training | 27 | 27 | 88 | 142 |

| Access to training, career advice/mentor, accreditation | 70 | 6 | 5 | 81 |

| Revalidation | 14 | 1 | 2 | 17 |

| Any of the above | 357 | |||

| Working in medicine | ||||

| NHS and government policy | 146 | 2 | 0 | 148 |

| NHS and its management | 109 | 0 | 0 | 109 |

| Experience of working outside NHS/medicine or abroad | 0 | 1 | 32 | 33 |

| Commitment to medicine/NHS/UK/job | 85 | 4 | 1 | 90 |

| Status, autonomy, morale, job satisfaction | 82 | 9 | 114 | 205 |

| Access to jobs, career options, security | 75 | 2 | 1 | 78 |

| Safety concerns, negligence, complaints, patient expectations | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

| Recruitment of juniors/workforce planning | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| Any of the above | 481 | |||

| Working conditions | ||||

| Family-friendly/part-time work, attitudes to gender, work-life balance | 109 | 24 | 27 | 160 |

| Workload and hours | 72 | 0 | 0 | 72 |

| Administration/paperwork | 53 | 0 | 0 | 53 |

| Pay, pension | 42 | 0 | 1 | 43 |

| Other | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Any of the above | 309 | |||

| Other | 9 | 51 | 5 | 65 |

| Total | 1133 | 131 | 280 | 1544 |

Some doctors commented on more than one theme and we counted each theme.

Declarations

Competing interests

None

Funding

This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health (project number 016/0118). Michael Goldacre is part-funded by Public Health England. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the funding bodies.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service, following referral to the Brighton and Mid-Sussex Research Ethics Committee in its role as a multi-centre research ethics committee (ref 04/Q1907/48).

Guarantor

All authors are guarantors.

Contributorship

TL and MJG designed and conducted the survey. FS performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors contributed to further drafts and all approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Emma Ayres for administering the surveys, Janet Justice and Alison Stockford for data entry. We are very grateful to all the doctors who participated in the surveys. All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and all authors want to declare: (1) financial support for the submitted work from the policy research programme, Department of Health. All authors also declare: (2) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) no spouses, partners, or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; and (4) no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Jacky Hayden

References

- 1.NHS Management Executive. Junior Doctors – the new deal, London: UK Department of Health, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Working Group on Specialist Medical Training. Hospital doctors: training for the future. (The Calman report), London: UK Department of Health, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Temple J. Time for training: a review of the impact of the European Working Time Directive on the quality of training, London: Medical Education England, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldacre MJ, Davidson JM, Lambert TW. Career choices at the end of the pre-registration year of doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1996. Med Educ 1999; 33: 882–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Edwards C, Parkhouse J. Career preferences of doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1993 compared with those of doctors qualifying in 1974, 1977, 1980, and 1983. BMJ 1996; 313: 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maisonneuve JJ, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. UK doctors’ views on the implementation of the European Working Time Directive as applied to medical practice: a quantitative analysis. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004391–e004391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarke RT, Pitcher A, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. UK doctors’ views on the implementation of the European Working Time Directive as applied to medical practice: a qualitative analysis. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e004390–e004390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans J, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. Views of junior doctors on the specialist registrar (SpR) training scheme: qualitative study of UK medical graduates. Med Educ 2002; 36: 1122–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia J, Evans J, Reshaw M. Is there anything else you would like to tell us – issues in the use of free-text comments from postal surveys. Qual Quant 2004; 38: 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow G, Burford B, Carter M and Illing J. The impact of the working time regulations on medical education and training: final report on primary research. A Report for the General Medical Council. Durham: Centre for Medical Education Research, Durham University, 2012.

- 11.British Medical Association. National survey of GP opinion 2011, London: BMA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goddard AF, Evans T, Phillips C. Medical registrars in 2010: experience and expectations of the future consultant physicians of the UK. Clin Med 2011; 11: 532–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rickard C, Smith T, Scallan S. A comparison of the learning experiences of full-time (FT) trainees and less than full-time (LTFT) trainees in general practice. Educ Primary Care 2012; 23: 399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozbilgin MF, Tsouroufli M, Smith M. Understanding the interplay of time, gender and professionalism in hospital medicine in the UK. Soc Sci Med 2011; 72: 1588–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, Bauer G, Hämmig O, Knecht M, et al. The impact of gender and parenthood on physicians’ careers – professional and personal situation seven years after graduation. BMC Health Serv Res 2010; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schueller-Weidekamm C, Kautzky-Willer A. Challenges of work-life balance for women physicians/mothers working in leadership positions. Gend Med 2012; 9: 244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]