Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is essential for many angiogenic processes both in normal conditions and in pathological conditions. However, the signaling pathways involved in VEGF-induced angiogenesis are not well defined. Protein kinase D (PKD), a newly described serine/threonine protein kinase, has been implicated in many signal transduction pathways and in cell proliferation. We hypothesized that PKD would mediate VEGF signaling and function in endothelial cells. Here we found that VEGF rapidly and strongly stimulated PKD phosphorylation and activation in endothelial cells via VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2). The pharmacological inhibitors for phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ) and protein kinase C (PKC) significantly inhibited VEGF-induced PKD activation, suggesting the involvement of the PLCγ/PKC pathway. In particular, PKCα was critical for VEGF-induced PKD activation since both overexpression of adenovirus PKCα dominant negative mutant and reduction of PKCα expression by small interfering RNA markedly inhibited VEGF-induced PKD activation. Importantly, we found that small interfering RNA knockdown of PKD and PKCα expression significantly attenuated ERK activation and DNA synthesis in endothelial cells by VEGF. Taken together, our results demonstrated for the first time that VEGF activates PKD via the VEGFR2/PLCγ/ PKCα pathway and revealed a critical role of PKD in VEGF-induced ERK signaling and endothelial cell proliferation.

Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood capillaries, is an important component of embryonic vascular development, wound healing, and organ regeneration, as well as pathological processes such as diabetic retinopathies, atherosclerosis, and tumor growth (1–3). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)2 is essential for many angiogenic processes both in normal conditions and in pathological conditions (4–7). VEGF receptors, VEGFR1 (Flt1) and VEGFR2 (mouse Flk1 or human KDR), are restricted in their tissue distribution primarily to endothelial cells (8). The binding of VEGF to its cognate receptors induces dimerization and subsequent phosphorylation of the receptors leading to the activation of several intracellular signaling molecules such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), protein kinase C (PKC), nitric oxide synthase, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and focal adhesion kinases (9–14). The importance of VEGF-induced signaling is demonstrated in that the genetic inactivation of either receptor leads to a complete lack of development of blood vessels in the embryo, and inactivation of VEGFR2 function dramatically impairs the growth of cancer cells in vivo (4–6). However, the intracellular signaling cascades downstream from the VEGF receptors are still not well understood.

Protein kinase D (PKD), also known as protein kinase Cμ (15, 16), is a newly described serine/threonine protein kinase with unique structural, enzymological, and regulatory properties that are different from those of the PKC family members. The most distinct characteristics of PKD are the presence of a catalytic domain distantly related to Ca2+-regulated kinases, a pleckstrin homology domain within the regulatory region, and a highly hydrophobic stretch of amino acids in its N-terminal region (17, 18). PKD can be activated by a variety of stimuli including biologically active phorbol esters, growth factors, and T- and B-cell receptor agonists via PKC-dependent pathways (17, 18). PKD activation appears to involve the phosphorylation of Ser-744 and Ser-748 within the activation loop of the catalytic domain (19) as well as the autophosphorylation of Ser-916 (18, 20). PKD has been implicated in the regulation of a variety of cellular functions, including signal transduction, membrane trafficking, protein transport, and cell survival, migration, differentiation, and proliferation (18, 21–26). PKD alters the signal pathway of the MAPK family external signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) (27, 28). For example, the stimulatory effect of PKD on vasopressin-induced cell proliferation has been linked to its ability to increase the duration of ERK1/2 signaling in Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts (27, 28). However, the regulation of PKD activation and its function in endothelial cells are very poorly studied.

The aim of this study was to determine whether and how VEGF activates PKD in endothelial cells and to examine the potential role of PKD in VEGF-mediated signal transduction. The results presented here demonstrated that VEGF rapidly induces activation of PKD via the VEGFR2/PLCγ/PKC pathway and that PKD is involved in VEGF-induced ERK signaling in endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Antibodies

VEGF and neutralization antibodies against VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 were from R&D System, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN). VTI (VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, 4-{(4′-chrolo-2′-fluoro) phenylamino}-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline), SU1498, U73122, LY294002, Wortmannin, GF109203X (bisindolylmaleimide I), Ro-31-8220, Rottlerin, Go6976, phorbol-12-myrisstate-13-acetate (PMA) were purchased from Calbiochem. Anti-phospho PKD antibodies (p-PKD(S744/748) and p-PKD(S916)) and anti-PKD antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA). Anti-VEGFR2 antibodies and Anti-β-actin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell Culture

Bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, CA) and were cultured in Medium 199 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) as described previously (29, 30). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated from human umbilical veins and grown in Medium 200 with low serum growth supplement (Cascade Biologics, Inc., Portland, OR) as described previously (30, 31). Confluent cells cultured in 60-mm dishes were serum-starved for 24 h and exposed to VEGF as indicated. For the inhibitor studies, cells were pretreated with various inhibitors for 30 min in serum-depleted medium.

Small Interference RNA (siRNA) and Its Transfection

To determine the contribution of VEGFR2, PKCα, and PKD in VEGF-stimulated signaling, we treated HUVEC with human VEGFR2, PKCα, or PKD siRNA duplex obtained from Dharmacon, Inc. (Chicago, IL). The scrambled siRNA control is a non-targeting siRNA pool from Dharmacon, Inc. For transfection of siRNA, HUVEC were seeded into 60-mm dishes for 24 h about 80% confluence, and then transfection of siRNA was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol as described previously (30). VEGF stimulation was performed 48 h after siRNA transfection.

Adenovirus Constructs and Infection

Adenovirus constructs encoding human VEGFR2 kinase-inactive mutant (VEGFR2-K868M) were kindly provided by Dr. Masabumi Shibuya (University of Tokyo, Japan) (9). Adenovirus constructs encoding mouse PKCα kinase-inactive mutant (PKCα-KD, K368R substitution) and rat PKCδ kinase-inactive mutant (PKCδ-KD, K376R substitution) were kindly provided by Dr. Trevor J. Biden (The Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia) (32). The infection of endothelial cells with recombinant adenovirus was performed as described previously (33). Briefly, endothelial cells cultured in 60-mm dishes were infected with recombinant adeno-virus at the indicated multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) in serum-free medium for 2 h and then incubated 24 h in a growth medium. Adeno-virus expressing β-galactosidase (Ad-LacZ) was used as a control.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were harvested in lysis buffer (0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 2.5 mm KCl, 150 mm NaCl, 30 mm β-glycerophosphate, 50 mm NaF, 1 mm Na3VO4, and 0.1% protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma)) and clarified by centrifugation as described previously (29, 30, 34). The protein concentrations in the lysates were determined using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad). The protein samples from total cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated with appropriate primary antibodies. After incubating with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies, immunoreactive proteins were visualized by an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology, Nebraska). Densitometric analyses of immunoblots were performed with Odyssey software (LI-COR Biotechnology). Results were normalized by arbitrarily setting the densitometry of control sample to 1.0.

DNA Synthesis

VEGF-stimulated DNA synthesis in endothelial cells was assayed by [3H]thymidine incorporation as described previously (34).

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as means ± S.E. The significance of the results was assessed by a paired t test. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

VEGF Stimulates PKD Activation in Endothelial Cells

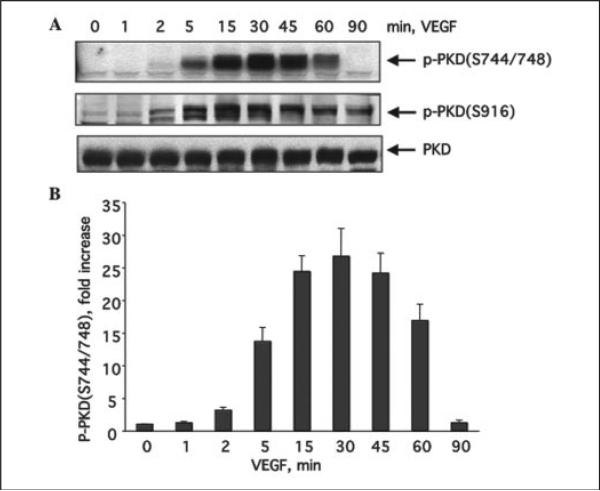

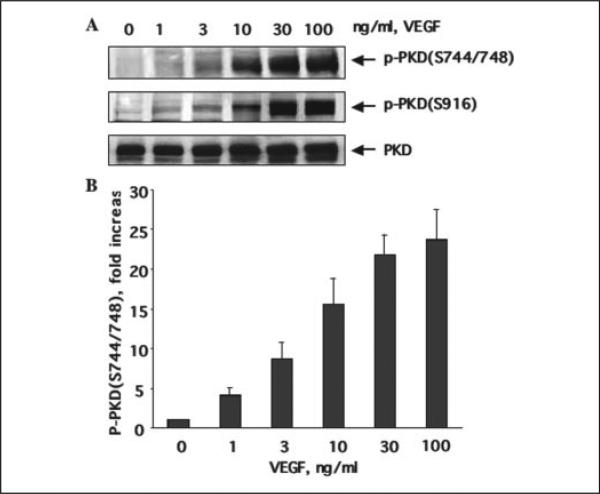

To examine whether VEGF induces PKD activation in endothelial cells, we studied PKD phosphorylation in BAEC in response to VEGF stimulation. Phosphorylation of PKD was determined by using two commercially available phospho-PKD-specific antibodies. One of them recognizes the endogenous levels of PKD only when dually phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748, and the other recognizes PKD only when phosphorylated at Ser-916. By using these antibodies, we observed for the first time that VEGF (25 ng/ml) rapidly induced PKD phosphorylation within 2 min, and the activation reached a maximum between 15 and 45 min and returned to basal line after 90 min (Fig. 1, A and B). PKD expression levels were detected by Western blots using anti-PKD antibody. During the course of VEGF stimulation, the levels of PKD expression in cells did not change (Fig. 1A). We also observed that VEGF induced PKD activation in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2). VEGF induced PKD activation at a concentration as low as 1 ng/ml and achieved maximal activation at 30–100 ng/ml (Fig. 2, A and B). In addition to BAEC, VEGF stimulated phosphorylation of PKD in HUVEC (see below Fig. 3B) and bovine lung microvascular endothelial cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 1. VEGF time-dependently stimulates PKD activation in endothelial cells.

A, BAEC were incubated with VEGF (25 ng/ml) for various times as indicated. PKD activation in cell lysates was analyzed by Western blot analysis using phospho-specific antibodies, which recognize the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748 (p-PKD(S744/748)) (first panel) and the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916 (p-PKD(S916)) (second panel). PKD expression levels were determined by Western blot using a PKD antibody (third panel). Representative immunoblots are shown. B, quantitative analysis of protein phosphorylation at Ser-744/Ser-748 for PKD (n = 3).

FIGURE 2. VEGF dose-dependently stimulates PKD activation.

A, BAEC were exposed to VEGF for 15 min with the different concentrations as indicated. PKD activation in cell lysates was determined by Western blot analysis using phospho-specific PKD antibodies as described in the legend for Fig. 1. PKD expression levels were determined by Western blot using a PKD antibody. Representative immunoblots (A) and quantitative analysis of protein phosphorylation at Ser-744/Ser-748 for PKD (B) are shown (n = 3). p-PKD(S744/ 748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; p-PKD(S916), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916.

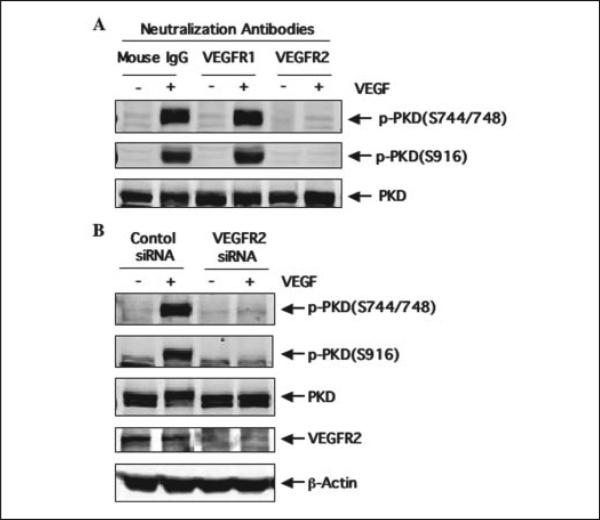

FIGURE 3. VEGFR2, but not VEGFR1, mediates VEGF-induced PKD activation.

A, HUVEC were pretreated with control mouse IgG, neutralizing antibodies against VEGFR1, or neutralizing antibodies against VEGFR2 (all for 2 μg/ml) for 30 min and then stimulated with VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. PKD activation and expression in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 1. p-PKD(S744/ 748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; p-PKD(S916), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916. B, HUVEC were transfected with control scrambled siRNA (100 nm) or human VEGFR2 siRNA (100 nm) for 48 h and then exposed to VEGF for 15 min. PKD activation and expression in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 1. VEGFR2 expression levels in cell lysates were also analyzed by Western blots with anti-VEGFR2 antibody to confirm the knockdown effect of VEGFR2 siRNA. β-actin was detected by reprobing the same blots with anti-β-actin antibodies to show the specificity of VEGFR2 siRNA. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown.

VEGFR2 Mediates VEGF-induced PKD Activation

VEGF functions are mediated, for the most part, by VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, and VEGFR2, but not VEGFR1, is responsible for VEGF-stimulated proliferation and migration of endothelial cells (10–12). To determine which subtype of VEGF receptors mediates VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells, we examined the effect of specific neutralization antibodies against VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 on PKD activation. These neutralizing antibodies blocked the receptor-ligand interaction. HUVEC were pretreated for 30 min with either neutralizing antibody (2 μg/ml) against human VEGFR1 or neutralizing antibody (2 μg/ml) against human VEGFR2 and then stimulated with VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. As shown in Fig. 3A, the neutralizing antibody against human VEGFR2 completely blocked PKD phosphorylation induced by VEGF, whereas the VEGFR1-specific neutralizing antibody had no effect on VEGF activation of PKD in HUVEC. These results suggested that VEGFR2 mediates VEGF-induced PKD activation.

To further determine the specific role of VEGFR2, we knocked down endogenous VEGFR2 expression in HUVEC with VEGFR2-specific siRNA. Transfection of HUVEC with human VEGFR2 siRNA, but not control siRNA, significantly reduced endogenous VEGFR2 expression (Fig. 3B, panel 4). VEGFR2 siRNA is specific for targeting VEGFR2 since expression of β-actin and PKD in cells was not changed (Fig. 3B, panels 3 and 5). Knockdown VEGFR2 expression in HUVEC blocked VEGF-induced PKD activation (Fig. 3B, panels 1 and 2). These data revealed that VEGF-induced PKD activation is specifically mediated by VEGFR2, but not by VEGFR1, in endothelial cells.

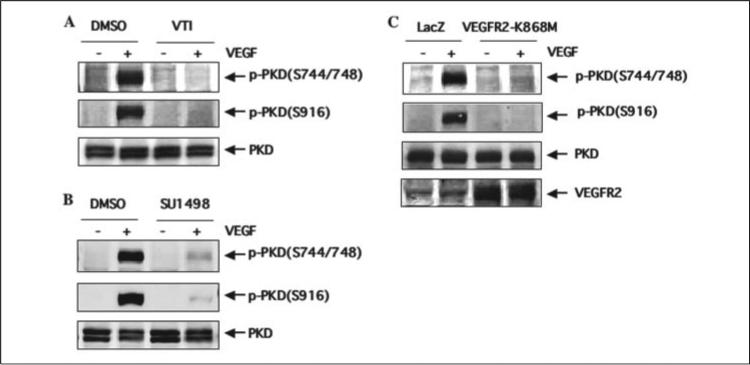

VEGFR2 Kinase Activity Is Essential for VEGF-induced PKD Activation

To determine the role of VEGFR2 kinase activation by VEGF in PKD activation, we first studied the effects of VTI and SU1498, two structurally different VEGFR2 kinase inhibitors. Pretreatment with VTI (10 μm) for 30 min almost completely abolished VEGF-mediated PKD activation (Fig. 4A). SU1498 (10 μm) also significantly inhibited activation of PKD by VEGF (Fig. 4B). To substantially determine the specific involvement of VEGFR2 kinase activity, we infected BAEC with adenovirus of VEGFR2 kinase-inactive mutant (VEGFR2-K868M) that has a dominant negative effect on VEGFR2 activation by VEGF (9). Overexpression of VEGFR2-K868M blocked VEGF-induced PKD phosphorylation (Fig. 4C). These data demonstrated that VEGFR2 activation is required for VEGF-induced activation of PKD in endothelial cells.

FIGURE 4. VEGFR2 kinase activity is required for VEGF-induced PKD activation.

A and B, BAEC were pretreated with VEGFR2 kinase inhibitors VTI (10 μm) or SU1498 (10 μm) for 30 min. The same amount of Me2SO (DMSO, the solvent for VTI and US1498) was added in control cells. Then BAEC were stimulated with VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. PKD activation and expression in cell lysates were analyzed by Western blots as described in the legend for Fig. 1. p-PKD(S744/748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; p-PKD(S916), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916. C, BAEC were infected with adenoviruses expressing β-galactosidase (Ad-LacZ, control) or expressing VEGFR2-K868M at 100 m.o.i. 24 h later, cells were exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. PKD activation and expression in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Expression levels of VEGFR2 in cell lysates were also analyzed by Western blots with anti-VEGFR2 antibody to show overexpression of VEGFR2-K868M in endothelial cells (C, fourth panel). Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown.

VEGF Stimulates PKD Activation through PLCγ-dependent Pathways

To determine whether PLCγ is involved in VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells, we examined the effect of a PLCγ-specific inhibitor, U73122, on PKD activation stimulated by VEGF. BAEC were first treated with U73122 (3 μm) for 30 min before exposure to VEGF. As shown in Fig. 5A, U73122 completely blocked PKD phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). In addition, we also examined whether phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin affect the activation of PKD. LY294002 and wortmannin did not inhibit VEGF-induced PKD activation (Fig. 5B). These data suggested that PLCγ, but not phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation, are required for VEGF-stimulated PKD activation in endothelial cells.

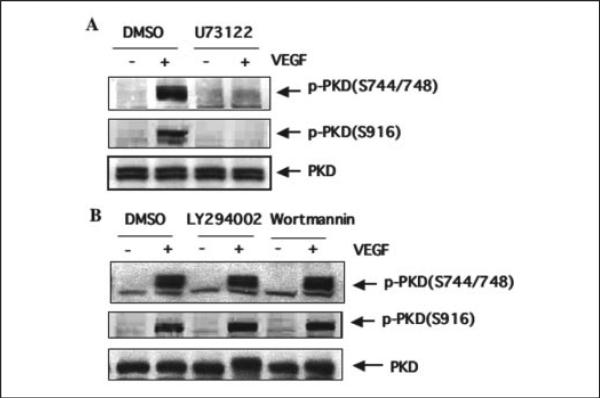

FIGURE 5. VEGF induces PKD activation through a PLCγ-dependent pathway.

BAEC were pretreated with PLCγ-selective inhibitor U73122 (3 μm, A) or phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors LY294002 (10 μm, B) and wortmannin (100 nm, B) for 30 min and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. PKD activation and expression in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown. p-PKD(S744/748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; p-PKD(S916), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916; DMSO, Me2SO.

PKCs Are Involved in VEGF-induced PKD Activation

PLCγ activation by VEGF triggers PKC activation (35), and it has been shown that PKD activation in intact cells is mediated through PKCs (18). To determine whether PKC activation is involved in VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells, we examined the effect of PKC inhibitors on PKD activation by VEGF. BAEC were treated with PKC inhibitors GF109203X or Ro-31-8220 for 30 min before exposure to VEGF. GF109203X at a concentration as low as 0.1 μm almost completely blocked PKD activation (Fig. 6A). VEGF-induced PKD activation was also blocked by Ro-31-8220 in a concentration-dependent fashion (Fig. 6B). These data suggested that PKCs are involved in the VEGF-stimulated PKD activation in endothelial cells.

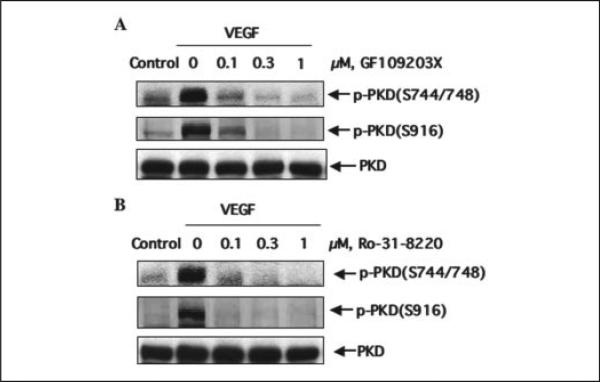

FIGURE 6. PKCs are involved in VEGF-induced PKD activation.

BAEC were pretreated with PKC inhibitors GF109203X (A) or Ro-31-8220 (B) at the different concentrations for 30 min and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. PKD activation and expression in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown. p-PKD(S744/748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; p-PKD(S916), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916.

PKCα Plays an Important Role in Mediating PKD Activation by VEGF in Endothelial Cells

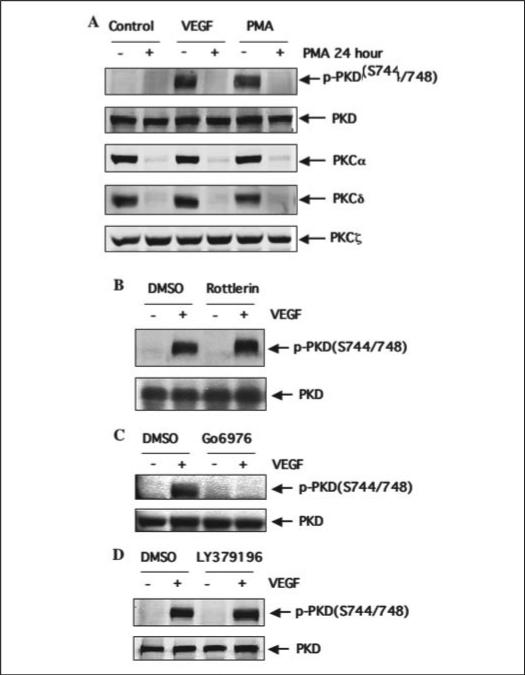

To assess the role of PKC isoforms in VEGF-induced PKD activation, endothelial cells were exposed to phorbol-12-myrisstate-13-acetate (PMA, 500 nm) for 24 h to deplete the classical and novel PKC isoforms, leaving only atypical isoforms active. Depletion of PKC by PMA, including PKCα and PKCδ, but not PKCξ (Fig. 7A), inhibited PKD activation induced by VEGF or PMA (500 nm, 10 min) (Fig. 7A). We next tested the effects of inhibitors of PKC isoforms with the aim of resolving which PMA-sensitive PKC isoforms are involved in PKD activation. We found that pretreatment of BAEC with Go6976 (a potent inhibitor of classical PKC isoforms) inhibited VEGF-induced PKD activation (Fig. 7C), whereas LY379196 (a selective PKCβ inhibitor) and Rottlerin (a PKCδ inhibitor) had no effect (Fig. 7, B and D). Inconsistently with several reports (36, 37), we did not detect PKCγ, a classical PKC isoform, in BAEC and HUVEC. On the basis of these findings, we hypothesized that PKCα was the principal PKC isoform necessary for VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells.

FIGURE 7. PKCδ and PKCβ are not involved in VEGF-induced PKD activation.

A, BAEC were pretreated with PMA (500 nm) for 24 h and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) or PMA (500 nm) for 15 min. B–D, BAEC were pretreated with the PKCδ inhibitor Rotterlin (5μm, B) or classical PKC inhibitor Go6976 (100 nm, B) and PKCβ inhibitor LY379196 (100 nm, D) for 30 min and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. PKD activation and expression in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown. p-PKD(S744/748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; DMSO, Me2SO.

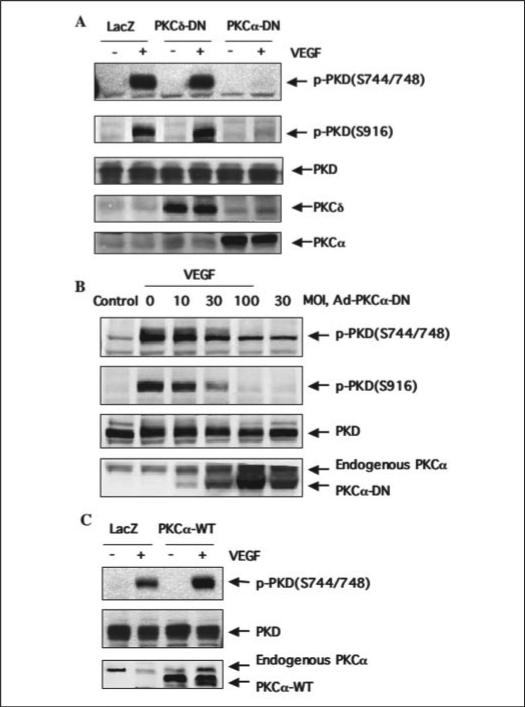

To determine the involvement of PKCα in the VEGF signaling to PKD activation in endothelial cells, we examined the effect of the dominant negative form of PKC (PKC-DN) on VEGF-induced PKD activation using adenovirus expression system. The dominant negative nature of the ATP-binding site mutant PKC has been previously characterized (32). Infection of BAEC with adenovirus constructs containing cDNAs for PKCα-DN and PKCδ-DN resulted in robust expression of these PKC isoforms (Fig. 8, A and B). At an m.o.i. of 100, PKCα-DN almost completely blocked VEGF-induced PKD activation as determined by measuring PKD phosphorylation at Ser-744/Ser-748 and Ser-916, whereas PKCδ-DN at the same m.o.i. had no significant effect on VEGF-induced PKD activation when compared with the effect of LacZ controls (Fig. 8A). We also found that the PKCα-DN inhibited VEGF-induced PKD activation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, infection of BAEC with recombinant adenovirus construct expressing the wild-type PKCα (PKCα-WT, 100 m.o.i.) enhanced PKD activation by VEGF when compared with the effect of LacZ controls (Fig. 8C). These data indicated that PKCα mediates VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells.

FIGURE 8. Adenovirus overexpression of dominant negative PKCα blocks VEGF-induced PKD activation.

A, BAEC were infected with adenovirus encoding control LacZ or PKCα-DN and PKCδ-DN at 100 m.o.i. for 24 h and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. p-PKD(S744/748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; DMSO, Me2SO. B, BAEC were infected with adenovirus encoding PKCα-DN at different concentrations for 24 h and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. C, BAEC were infected with adenovirus encoding control LacZ or PKCα-WT at 100 m.o.i. for 24 h and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. PKD activation and expression and PKCα and PKCδ expression in cell lysates were determined by Western blot analysis as described in the legend for Fig. 1. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown.

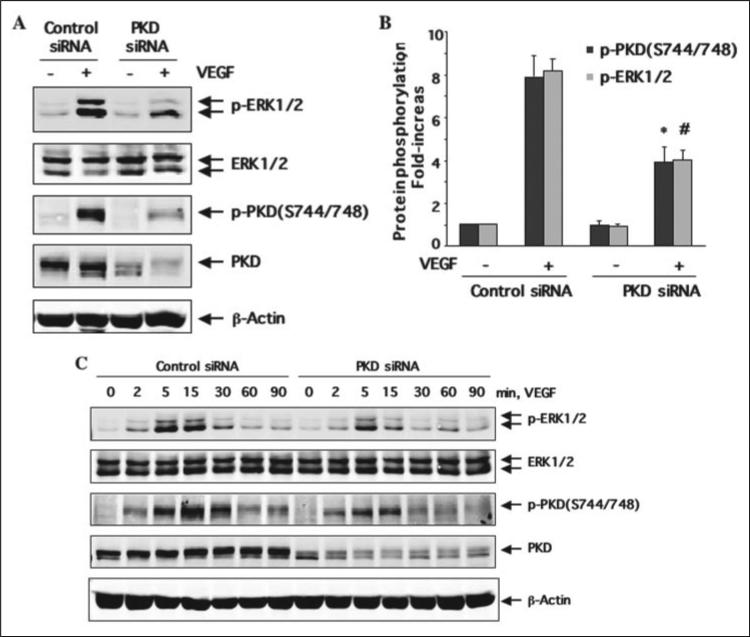

Knockdown of PKD by siRNA Inhibited VEGF-induced Activation of ERK in Endothelial Cells

VEGF-dependent activation of the PLCγ/ PKC pathway contributes to ERK1/2 activation via Raf-MEK1 (MAPK kinase 1) and DNA synthesis in vascular endothelial cells (9, 14, 35, 38). To gain insight into the functional significance of PKD activation in VEGF-mediated signaling events, we determined whether knockdown of endogenous PKD in endothelial cells using siRNA affects VEGF-mediated ERK1/2 activation. HUVEC were transfected with human PKD siRNA for 48 h and then stimulated with VEGF for the time indicated. Treatment of HUVEC with PKD siRNA significantly reduced endogenous PKD expression, whereas control siRNA had no effect (Fig. 9, A and C). PKD siRNA is specific for targeting PKD since expression of β-actin and ERK1/2 was not changed (Fig. 9). Decreasing PKD expression by its siRNA significantly inhibited VEGF-induced ERK1/2 in HUVEC (Fig. 9, A and B). Statistical data showed that 50% reduction of PKD activation due to its siRNA treatment is correlated to about 50% decrease of ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, the experiments for the time course of VEGF treatment also showed that PKD siRNA inhibited the magnitude and duration of ERK activation by VEGF in endothelial cells (Fig. 9C).

FIGURE 9. Knockdown of PKD expression by siRNA inhibits VEGF-induced ERK1/2 activation.

HUVEC were transfected with scrambled siRNA (100 nm, control) or human PKD siRNA (100 nm) for 48 h and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min (A and B) or the different times as indicated (C). ERK1/2 activation in cell lysates was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-phopho-ERK1/2 antibodies. The amount of ERK1/2 was detected by Western blots with anti-ERK1/2 antibodies. PKD activation in cell lysates was determined by Western blot analysis using phospho-specific PKD antibodies as described in the legend for Fig. 1. PKD expression levels in cell lysates were also analyzed by Western blot with a PKD antibody to confirm the knockdown effect of VEGFR2 siRNA. β-actin was detected by reprobing the same blots with anti-β-actin antibodies to show the specificity of PKD siRNA. Representative immunoblots (A and C) and quantitative analysis of protein phosphorylation for both PKD and ERK1/2 (B) are shown (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 when compared with control siRNA plus VEGF for PKD phosphorylation; #, p < 0.05 when compared with control siRNA plus VEGF for ERK1/2 phosphorylation. p-PKD(S744/748), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-744 and Ser-748; p-PKD(S916), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916. p-ERK1/2, the phosphorylated ERK1/2.

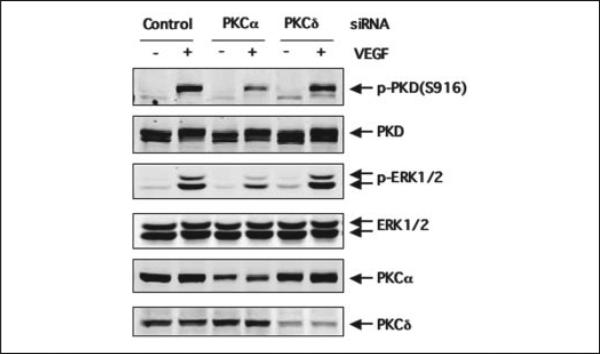

Knockdown of PKCα by siRNA Inhibited VEGF-induced Activation of PKD and ERK in Endothelial Cells

To further confirm the critical role of PKCα in VEGF-induced PKD activation as well as its downstream signaling, we determined whether siRNA knockdown of endogenous PKCα in endothelial cells affects VEGF-mediated activation of PKD and ERK1/2. HUVEC were transfected with human PKCα siRNA or PKCδ siRNA for 48 h and then stimulated with VEGF for 15 min. Treatment of HUVEC with PKCα siRNA and PKCδ significantly reduced endogenous PKCα and PKCδ expression, respectively, whereas control siRNA had no effect (Fig. 10). Decreasing PKCα expression by siRNA significantly inhibited VEGF-induced activation of PKD and ERK1/2 in HUVEC (Fig. 10, A and B). In contrast, decreasing PKCδ expression by siRNA had no significant effect on both PKD activation and ERK1/2 activation by VEGF in HUVEC (Fig. 10).

FIGURE 10. siRNA knockdown of PKCα expression attenuated VEGF-induced PKD and ERK1/2 activation.

HUVEC were transfected with scrambled siRNA (100 nm, control) or human PKCα siRNA (100 nm) and PKCδ siRNA (100 nm) for 48 h and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 15 min. The activation of PKD and ERK1/2 and the expression of PKD, ERK1/2, PKCα, and PKCδ in cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with the corresponding antibodies as described in the legends for Figs. 8 and 9. Representative immunoblots from three independent experiments are shown. p-PKD(S916), the PKD phosphorylated at Ser-916; p-ERK1/2, the phosphorylated ERK1/2.

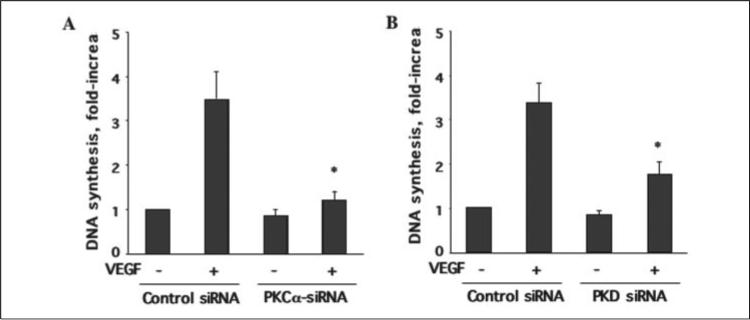

PKCα/PKD Pathway Is Involved in VEGF-induced DNA Synthesis in Endothelial Cells

VEGF-dependent activation of the ERK pathway contributes to DNA synthesis and cell proliferation in vascular endothelial cells (9, 14, 35, 38). To determine whether PKD plays an important role in VEGF-induced endothelial cell proliferation, we examined the effect of PKD and PKCα siRNA on VEGF-induced DNA synthesis in HUVEC using a [3H]thymidine incorporation assay (34). As shown in Fig. 11, both PKD and PKCα siRNA significantly inhibited DNA synthesis in endothelial cells by VEGF (Fig. 11).

FIGURE 11. siRNA knockdown of PKCα and PKD expression inhibited VEGF-stimulated DNA synthesis in endothelial cells.

HUVEC were transfected with scrambled siRNA (100 nm, control) or human PKCα siRNA (100 nm) and PKD siRNA (100 nm) for 48 h and then exposed to VEGF (25 ng/ml) for 24 h. The DNA synthesis was determined with [3H]thymidine incorporation assay. The quantitative analysis of PKCα siRNA (A) and PKD siRNA (B) effects on VEGF-stimulated DNA synthesis are shown (n = 3). *, p < 0.05 when compared with the control siRNA plus VEGF.

DISCUSSION

The major findings of the present study were that VEGF stimulates activation of PKD via the VEGFR2/PLCγ/PKCα pathway and that PKD is involved in VEGF-induced ERK signaling and endothelial cell proliferation. We found that PKD is rapidly phosphorylated at Ser-744/Ser-748 and Ser-916 in endothelial cells in response to VEGF. Both VEGFR2-specific neutralization antibodies and VEGFR2 siRNA treatment abolished VEGF-stimulated PKD activation. VEGFR2 kinase inhibitors and overexpression of adenovirus VEGFR2 kinase-inactive mutant blocked VEGF-induced PKD activation. Furthermore, inhibition of the activation of PLCγ and PKC by their pharmacological inhibitors significantly reduced PKD activation by VEGF. In particular, PKCα was critical for mediating PKD activation by VEGF since both overexpression of PKCα-DN and reduction of PKCα expression by siRNA markedly inhibited VEGF-induced PKD activation. Finally, knockdown of PKD by siRNA attenuated VEGF-induced activation of ERK1/2 in endothelial cells. This is the first report to show the rapid activation of PKD in endothelial cells by VEGF and reveal a critical role of PKD in the VEGF-mediated ERK1/2 pathway and endothelial cell proliferation.

PKD not only is a direct diacylglycerol target but also lies downstream of PKCs in a novel signal transduction pathway implicated in the regulation of multiple fundamental biological processes (18). In addition to the biologically active phorbol esters, a variety of regulatory peptides, including G-protein-coupled receptor ligands (e.g. bombesin, vasopressin, and thrombin) or growth factors (e.g. epithelial growth factor), induced PKD activation in fibroblast and vascular smooth muscle cells (17, 18, 39, 40). However, so far, few studies have reported on the regulation of PKD in endothelial cells. In this study, we showed that PKD is well expressed in all types of endothelial cells we tested, including BAEC and HUVEC. Stimulation of endothelial cells with VEGF leads to a rapid and transient activation of PKD, occurring within minutes of VEGF stimulation of cells. We also observed that VEGF induced PKD activation in a concentration-dependent manner. These results suggested that PKD activation is one of the early signaling events in endothelial cells in response to VEGF stimulation.

On endothelial cells, VEGF binds to VEGFR1 and VEGFR2. VEGFR1 is poorly autophosphorylated in response to VEGF in endothelial cells (41). In contrast, ligand-induced homodimerization of VEGFR2 leads to a strong autophosphorylation of VEGFR2 on tyrosine residues, which triggers activation of major signaling pathways that include PLCγ and PKCs (9, 13, 14, 35, 38). In the present study, we examined which sub-type of VEGF receptors mediates VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells using multiple strategies. We observed that neutralizing antibodies of VEGFR2, but not VEGFR1, blocked VEGF-induced PKD activation. Down-regulation of VEGFR2 by its siRNA inhibited PKD activation. Moreover, selective VEGFR2 kinase inhibitors VTI and SU1498 as well as VEGFR2 dominant negative mutant (kinase-dead form) abolished VEGF-induced PKD activation. These data indicated that VEGF-induced PKD activation is specifically mediated by VEGFR2, but not VEGFR1, in endothelial cells.

PKD can be activated via PKC-dependent and -independent pathways (18, 21, 39, 42, 43). In this study, we found that the PLCγ/PKC pathway is involved in VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells. PLCγ-specific inhibitor U73122 completely blocked PKD activation by VEGF, and the PKC inhibitors GF 109203X and Ro 31-8220 also markedly inhibited VEGF-induced PKD activation in a concentration-dependent manner. Six PKC isoforms(α, β1, β2, δ, ε, and ξ) are expressed in BAEC and HUVEC. Among them, PKCα and PKCβ2 are strongly activated by VEGF in endothelial cells (38). Inaddition, we also found that VEGF stimulated PKCδ activation in BAEC and HUVEC (data not shown). Many PKC isoforms, such as PKCδ, PKCε, PKCη, and PKCθ, can activate PKD (18). The PKC isoforms that mediate PKD activation may vary in response to the specific cellular stimuli in different cell types (40). Our results revealed a novel signaling pathway in which PKCα mediates VEGF-induced PKDactivation. To date, the role of PKCα in PKD activation is totally unknown, and although VEGF has been shown to activate PKCα in endothelial cells (38), the down stream target of PKCα is still unclear. Our data established for the first time that VEGF-induced PKD activation is mediated by PKCα in endothelial cells.

We applied multiple approaches to address the specificity of the PKCα function in mediating VEGF-induced PKD activation. First, the prolonged treatment with PMA blocked VEGF-induced PKD activation (Fig. 7A), suggesting that classical or novel PKC isoforms are involved in VEGF-induced PKD activation. Next, the fact that the PKCδ inhibitor Rottlerin and the PKCβ inhibitor LY379196 did not affect VEGF-induced PKD activation excludes the involvement of PKCδ and PKCβ2 in VEGF-induced PKD activation. To determine the role of PKCα, we employed the dominant negative approach by using the adenovirus expression system to express the wild-type and dominant negative forms of PKCα in endothelial cells. Our results showed that overexpression of PKCα-DN almost completely blocks VEGF-induced PKD activation in a dose-dependent manner. In contrast, PKCδ-DN did not affect VEGF-induced PKD activation (Fig. 8). In addition, overexpression of PKCα-WT enhanced VEGF-induced PKD activation. Finally, siRNA knockdown of PKCα, but not PKCδ, expression in HUVEC significantly inhibited VEGF-induced PKD activation. Collectively, these data demonstrated a novel role of PKCα in mediating VEGF-induced PKD activation in endothelial cells.

The signal transduction pathways mediate VEGF biological function, such as stimulating cell proliferation and migration and increasing vascular permeability and angiogenesis. In particular, it has been suggested that the VEGF-stimulated VEGFR2/PLCγ/PKC pathway leads to activation of Raf-MEK1-ERK1/2 and endothelial cell proliferation as well as angiogenesis (9, 13, 14, 35, 38). Since we found that VEGF induced PKD activation via the VEGFR2/PLCγ/PKCα pathway, we asked whether PKD and PKCα are involved in VEGF-mediated ERK1/2 signaling and cell proliferation. Using the loss-of-function approach with siRNA targeting, we found that siRNA knockdown of PKD and PKCα expression significantly attenuated ERK1/2 activation and DNA synthesis by VEGF in endothelial cells. Our results indicated a critical role of PKD in VEGF-induced ERK1/2 signaling and endothelial cell proliferation. Consistent with our results, it has been reported that constitutively activated PKD mutant selectively activates the Raf-MEK1-ERK1/2 pathway (44) and that overexpression of wild-type PKD potentiates ERK1/2 signaling and DNA synthesis induced by G-protein-coupled receptors (28).

In summary, our study demonstrated for the first time that VEGF activated PKD in endothelial cells. Our results also revealed a VEGFR2/ PLCγ/PKCα pathway in VEGF-induced PKD activation. Furthermore, our experiments provided evidence of a critical role of PKD in VEGF-induced ERK1/2 signaling and endothelial cell proliferation. Thus, the present findings identified PKD as a new component in the VEGF-induced intracellular signaling pathway in endothelial cells, and this discovery may implicate PKD in mediating angiogenesis by VEGF and may suggest PKD as a potential therapeutic target for angiogenesis in various diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Masabumi Shibuya for adenovirus VEGFR2 constructs and Dr. Trevor J Biden for adenovirus PKCα and PKCδ constructs.

Footnotes

This work was supported by American Heart Association Grant 0235480T and National Institutes of Health Grant HL080611 (to Z. J.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The abbreviations used are: VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGFR1: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1; VEGFR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; PLCγ, phospholipase Cγ; PKC, protein kinase C; PKD, protein kinase D; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; ERK, external signal-regulated kinase; MEK1, MAPK kinase 1; VTI, VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor; BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cells; HUVEC, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; siRNA, small interference RNA; m.o.i., multiplicity of infection; PMA, phorbol-12-myrisstate-13-acetate; WT, wild type; DN, dominant negative.

REFERENCES

- 1.Folkman J. Nat. Med. 1995;1:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. Nat. Med. 2003;9:669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carmeliet P. Nat. Med. 2003;9:653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M, Breitman ML. Nature. 1995;376:66–70. doi: 10.1038/376066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalaby F, Rossant J, Yamaguchi TP, Gertsenstein M, Wu XF, Breitman ML, Schuh AC. Nature. 1995;376:62–66. doi: 10.1038/376062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, Fahrig M, Vandenhoeck A, Harpal K, Eberhardt C, Declercq C, Pawling J, Moons L, Collen D, Risau W, Nagy A. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrara N, Carver-Moore K, Chen H, Dowd M, Lu L, O'Shea KS, Powell-Braxton L, Hillan KJ, Moore MW. Nature. 1996;380:439–442. doi: 10.1038/380439a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Nature. 2000;407:242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi T, Yamaguchi S, Chida K, Shibuya M. EMBO J. 2001;20:2768–2778. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karkkainen MJ, Petrova TV. Oncogene. 2000;19:5598–5605. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zachary I. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:1171–1177. doi: 10.1042/bst0311171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claesson-Welsh L. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003;31:20–24. doi: 10.1042/bst0310020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawson ND, Mugford JW, Diamond BA, Weinstein BM. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1346–1351. doi: 10.1101/gad.1072203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakurai Y, Ohgimoto K, Kataoka Y, Yoshida N, Shibuya M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:1076–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404984102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valverde AM, Sinnett S-J, Van L-J, Rozengurt E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1994;91:8572–8576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johannes FJ, Prestle J, Eis S, Oberhagemann P, Pfizenmaier K. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:6140–6148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lint JV, Rykx A, Vantus T, Vandenheede JR. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34:577–581. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rozengurt E, Rey O, Waldron RT. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13205–13208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500002200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iglesias T, Waldron RT, Rozengurt E. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27662–27667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews SA, Rozengurt E, Cantrell D. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26543–26549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamora C, Yamanouye N, Van Lint J, Laudenslager J, Vandenheede JR, Faulkner DJ, Malhotra V. Cell. 1999;98:59–68. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liljedahl M, Maeda Y, Colanzi A, Ayala I, Van Lint J, Malhotra V. Cell. 2001;104:409–420. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baron CL, Malhotra V. Science. 2002;295:325–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1066759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hausser A, Link G, Bamberg L, Burzlaff A, Lutz S, Pfizenmaier K, Johannes FJ. J. Cell Biol. 2002;156:65–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200110047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storz P, Toker A. EMBO J. 2003;22:109–120. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeaman C, Ayala MI, Wright JR, Bard F, Bossard C, Ang A, Maeda Y, Seufferlein T, Mellman I, Nelson WJ, Malhotra V. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004;6:106–112. doi: 10.1038/ncb1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brandlin I, Hubner S, Eiseler T, Martinez-Moya M, Horschinek A, Hausser A, Link G, Rupp S, Storz P, Pfizenmaier K, Johannes FJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6490–6496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinnett-Smith J, Zhukova E, Hsieh N, Jiang X, Rozengurt E. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:16883–16893. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313225200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin ZG, Ueba H, Tanimoto T, Lungu AO, Frame MD, Berk BC. Circ. Res. 2003;93:354–363. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089257.94002.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin ZG, Wong C, Wu J, Berk BC. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:12305–12309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500294200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin ZG, Lungu AO, Xie L, Wang M, Wong C, Berk BC. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1186–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000130664.51010.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carpenter L, Cordery D, Biden TJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:5368–5374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lungu AO, Jin ZG, Yamawaki H, Tanimoto T, Wong C, Berk BC. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:48794–48800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin ZG, Melaragno MG, Liao DF, Yan C, Haendeler J, Suh YA, Lambeth JD, Berk BC. Circ. Res. 2000;87:789–796. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi T, Ueno H, Shibuya M. Oncogene. 1999;18:2221–2230. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosales OR, Isales C, Nathanson M, Sumpio BE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;189:40–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91522-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traub O, Monia BP, Dean NM, Berk BC. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:31251–31257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia P, Aiello LP, Ishii H, Jiang ZY, Park DJ, Robinson GS, Takagi H, Newsome WP, Jirousek MR, King GL. J. Clin. Investig. 1996;98:2018–2026. doi: 10.1172/JCI119006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zugaza JL, Waldron RT, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23952–23960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan M, Xu X, Ohba M, Ogawa W, Cui MZ. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:2824–2828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrova TV, Makinen T, Alitalo K. Exp. Cell Res. 1999;253:117–130. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zugaza JL, Sinnett-Smith J, Van Lint J, Rozengurt E. EMBO J. 1996;15:6220–6230. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Endo K, Oki E, Biedermann V, Kojima H, Yoshida K, Johannes FJ, Kufe D, Datta R. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:18476–18481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hausser A, Storz P, Hubner S, Braendlin I, Martinez-Moya M, Link G, Johannes FJ. FEBS Lett. 2001;492:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]