Abstract

Case series

Patient: —

Final Diagnosis: —

Symptoms: —

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: —

Objective:

Unexpected drug reaction

Background:

Increases in tumor marker concentrations usually suggest disease progression.

Cases Report:

We here describe on 3 patients with non-small cell lung cancer whose serum concentrations of CYFRA21-1 increased in spite of successful treatment with crizotinib. Discontinuation of crizotinib resulted in a rapid decrease in serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations in all cases. In 1 patient with progressive disease, in spite of increasing the dose of crizotinib, CYFRA21-1 concentrations decreased.

Conclusions:

Crizotinib can induce increases in CYFRA21-1 concentration without disease progression. Pulmonologists and oncologists should be aware of this novel phenomenon, and focus on interpretation of CYFRA21-1 concentrations in monitoring tumor response to crizotinib treatment.

MeSH Keywords: Adenocarcinoma; Keratin-19; Lung Neoplasms; Molecular Targeted Therapy; Pericardial Effusion; Tumor Markers, Biological

Background

Cytokeratin 19 fragment (CYFRA) 21-1 is widely used as a tumor marker for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). High serum concentrations of CYFRA21-1 are associated with a poor prognosis [1–3]. In a subset of NSCLC patients with fusions in the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene, crizotinib, an ALK inhibitor, has been found to be effective and well tolerated, with few adverse events [4]. Tumor markers, including CYFRA21-1, generally decrease in response to successful treatment of cancer. We here report that crizotinib can induce increases in serum concentrations of CYFRA21-1 in spite of achieving tumor regression in patients with NSCLC.

Cases Report

Case 1

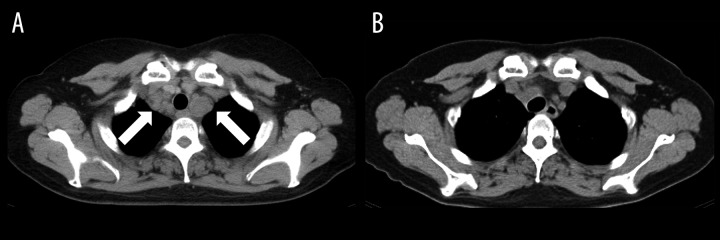

A 50-year-old woman was diagnosed with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC (adenocarcinoma). Pleural dissemination was recognized on CT and clinical staging was T2aN3M1a (PLE), Stage IV. Chemotherapy with carboplatin and pemetrexed was administered as the first-line therapy. Four cycles of chemo-therapy resulted in a partial response, and maintenance therapy with pemetrexed was subsequently administered. After 5 cycles of pemetrexed monotherapy, her disease progressed (Figure 1A). Laboratory test results were: aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 35 U/L, alanine transaminase (ALT) 25 U/L, serum creatinine 0.61 mg/dl, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 79.7 ml/min. Crizotinib (one 250-mg capsule, twice daily) was prescribed as second-line treatment. One month after commencing crizotinib, all tumors, including the primary lesion and mediastinal and cervical lymph node metastases, had regressed significantly and serum concentrations of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) had decreased from 90.9 to 10.9 ng/mL. In contrast, CYFRA21-1 had increased from 6.0 to 16.7 ng/mL. After 3 months of crizotinib treatment, her CYFRA21-1 had further increased (to 30.2 ng/mL), whereas CEA had decreased to within the normal range (4.3 ng/mL). A CT scan showed significant regression of all tumor lesions (Figure 1B); however, a pericardial effusion of uncertain etiology was detected. Positron emission tomography (PET) showed no abnormal accumulation of fluorodeoxyglucose. In addition, no brain metastases were detected by a gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI. It was considered that crizotinib had produced a partial response. The patient proposed reducing her dose of crizotinib because of its expense; her dose was accordingly decreased to 250 mg per day. After 6 weeks of treatment with this lower dose, CFRA21-1 concentrations dramatically decreased to 6.4 ng/mL and pericardial effusion had also decreased. After an additional 2 months, her tumors had progressed and she developed bacterial pneumonia. Treatment with crizotinib was stopped. Because her disease had progressed while on docetaxel, she resumed treatment with crizotinib at a dose of 200 mg twice daily. Over the next 2 months, her CYFRA21-1 concentration increased from 6.1 to 12.9 ng/mL and she was assessed as having stable disease, which was accompanied by a slight decrease in CEA concentration. Pericardial effusion did not increase during the second treatment with crizotinib. Renal and hepatic functions as assessed by serum concentrations of creatinine and transaminases maintained at normal levels during the course of crizotinib treatment.

Figure 1.

Chest CT of Case 1 before (A) and after (B) crizotinib treatment. Arrows show mediastinal lymph nodes.

Case 2

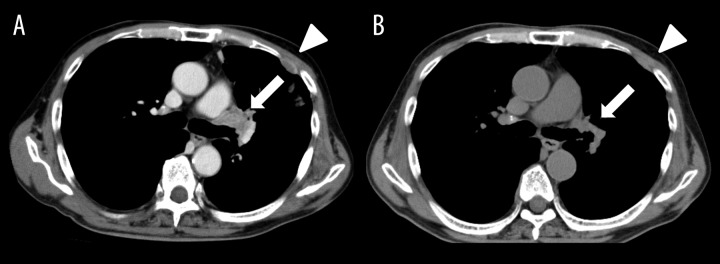

A 65-year-old man was diagnosed with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC (adenocarcinoma). Clinical stage was T4N3M1b (OSS, BRA, HEP, PLE), Stage IV. Chemotherapy with carboplatin and pemetrexed was administered as the first-line therapy and whole-brain irradiation was performed for multiple brain metastases. Although 3 cycles of chemotherapy resulted in stable disease, chemotherapy was stopped due to adverse effects (loss of appetite and general fatigue). Laboratory test results were: AST 33 U/L, ALT 27 U/L, serum creatinine 0.89 mg/dl, and eGFR 66.5 ml/min. He was started on treatment with crizotinib at a dose of 250 mg twice daily. Three weeks later, the primary lesion, as well as mediastinal lymph node and liver metastases, had regressed and he was assessed as having a partial response (Figure 2A, 2B). However, crizotinib was discontinued because of evidence of impairment of hepatic function (increased serum concentrations of AST and ALT, up to 259 and 482 U/L, respectively). After these enzyme concentrations had decreased, crizotinib was restarted at a dose of 200 mg per day, at which time a decrease in serum CEA concentration was found, from a pretreatment level of 611.1 ng/mL to 51.6 ng/mL. In contrast, CYFRA21-1 concentration had increased from 2.6 ng/mL to 16.4 ng/mL. Two months after commencing crizotinib (200 mg per day), all tumor lesions regressed a little further and both CEA and CYFRA21-1 concentrations had decreased (to 21.8 and 5.6 ng/mL, respectively). Renal function assessed by serum creatinine concentrations remained at normal levels during the course of crizotinib treatment.

Figure 2.

Chest CT of Case 2 before (A) and after (B) crizotinib treatment. Arrows show primary lesion and arrowheads show pleural dissemination.

Case 3

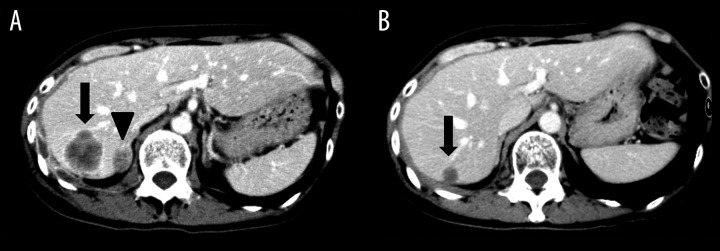

A 56-year-old woman was diagnosed with advanced NSCLC (adenocarcinoma). Clinical stage was T2bN2M1b (LYM, PLE), Stage IV at the diagnosis. She was treated with several different chemotherapies (cisplatin and pemetrexed, carboplatin and docetaxel, vinorelbine, and gemcitabine). In the course of disease, liver and adrenal metastases developed (Figure 3A). Re-biopsy from the tumor revealed that the tumor was positive for ALK. Laboratory test results were: AST 17 U/L, ALT 8 U/L, serum creatinine 0.57 mg/dl, and eGFR 83.5 ml/min. She was started on treatment with crizotinib at a dose of 250 mg twice daily as the fifth-line therapy. Two months later, esophageal ulcer was diagnosed and crizotinib was discontinued. After recovery from the esophageal ulcer, she was prescribed crizotinib at a dose of 200 mg daily with adequate fluid intake. Crizotinib produced a partial response (Figure 3B). Nine months later, her CYFRA21-1 concentration had increased to 25.2 ng/mL, although it had been within the normal range (2.3 ng/mL) at the time of diagnosis. At this stage, a CT scan showed slight tumor progression and her dose of crizotinib was increased to 400 mg per day. Two months later, her disease had progressed further and CYFRA21-1 had decreased slightly (20.4 ng/mL). Crizotinib was discontinued. One month later her CYFRA21-1 concentration had decreased rapidly to 5.6 ng/mL. Renal and hepatic functions as assessed by serum concentrations of creatinine and transaminases remained at normal levels during the course of crizotinib treatment.

Figure 3.

Abdominal CT of Case 3 before (A) and after (B) crizotinib treatment. Arrows show liver metastasis and arrowhead shows an adrenal metastasis.

Discussion

We treated 5 patients with crizotinib but CYFRA21-1 concentrations were measured after crizotinib treatment in only 3 of them. In the other 2 patients treated with crizotinib, CYFRA21-1 concentrations were within normal range at diagnosis and CYFRA21-1 concentrations were not measured after crizotinib treatment. Here, we presented 3 patients for whom data on CYFRA21-1 concentrations were available. These 3 cases demonstrate a clear association between crizotinib use and increased serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations. A summary of the 3 cases is shown in Table 1. Drug-induced increase in CYFRA21-1 concentrations has never before been reported, not only for crizotinib, but also for other anti-cancer drugs and molecular-targeting drugs. In general, serum concentrations of CYFRA21-1 parallel tumor burden; thus, decreases in response to chemotherapy are associated with a favorable prognosis [5]. High serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations after adjuvant chemotherapy reportedly predict poor prognosis and decreased survival [6].

Table 1.

Summary of findings in patients with increased serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations in response to crizotinib.

| Case | Dose (per day), duration of crizotinib therapy | Outcome | Serum CYFRA21-1 (ng/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before commencing crizotinib | During crizotinib therapy | After decreasing or discontinuing crizotinib | |||

| 1 | 500 mg, 3 months | PR | 6.0 | 30.2 | 6.4 |

| 400 mg, 2 months | SD | 6.1 | 12.9 | N/A | |

| 2 | 500 mg, 3 weeks | PR | 2.6 | 16.4 | 5.6 |

| 3 | 200 mg, 9 months | PR | 2.3 | 25.2 | N/A |

| 400 mg, 2 months | PD | N/A | 20.4 | 5.6 | |

PR – partial response; SD – stable disease; PD – progressive disease; N/A – not available.

A possible mechanism of crizotinib-induced increases in CYFRA21-1 concentrations might be tumor lysis. Because CYFRA21-1 consists of cytokeratin 19 fragments, its serum concentration could increase when cancer cells die in response to treatment if those cells express cytokeratin 19 strongly. In all 3 cases presented here, crizotinib had produced a partial response or stable disease in association with increased CYFRA21-1 concentrations. In contrast, CYFRA21-1 later decreased slightly in association with ongoing progressive disease in Case 3, in spite of increasing the dose of crizotinib. These findings suggest that increased CYFRA21-1 concentrations can reflect cancer cell death, which is a positive response to crizotinib treatment, unlike that which occurs with chemotherapy. Crizotinib might have different kinetics from that seen in treatment using the classical cytotoxic drugs. In Case 1, serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations increased progressively until the dose of crizotinib was reduced; this patient’s tumors significantly regressed within the first month of crizotinib treatment. However, in Case 2, after decreasing the crizotinib dose, CYFRA21-1 concentrations decreased, and the patient’s tumor lesions further regressed. These findings suggest that increases in CYFRA21-1 concentration do not always parallel tumor regression – they may simply be related to crizotinib dose. Further studies are needed to clarify the association between CYFRA21-1 concentrations and tumor responsiveness to crizotinib treatment.

Another possible explanation of our findings is that the CYFRA21-1 came from cells other than cancer cells. Cytokeratin 19 is expressed broadly in a variety of tissues and organs, particularly in stratified and simple epithelial tissues [7]. In Case 1, pericardial effusion developed during crizotinib treatment. It has been reported that CYFRA21-1 concentrations in non-malignant pericardial effusion, but not in serum, average 22.4 ng/mL [8], suggesting that the pericardium can be a source of CYFRA21-1. However, no pericardial effusions were diagnosed in Case 2 and Case 3. In addition, pericardial effusion did not increase during the second treatment in Case 1 (400 mg of crizotinib), suggesting that pericardial effusion was unrelated to increased serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations in this case. In Case 2, liver injury was observed. There is no previous publication reporting that liver injury can increase serum CYFRA21-1 concentration. However, we cannot rule out an association between liver injury and increase in CYFRA21-1 concentration in Case 2. In Case 3, increased CYFRA21-1 concentration was observed 9 month after recovery from the esophageal ulcer, suggesting it was less likely due to esophageal ulcer. Serum CYFRA21-1 can also increase in interstitial lung diseases (ILD) such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and collagen disease-associated pulmonary fibrosis [9]. Crizotinib induces ILD in about 2% of patients [10, 11]. Although serum CYFRA21-1 concentrations might elevate in crizotinib-induced ILD, this serious adverse effect was not observed in any of our cases reported here.

Furthermore, decreased renal clearance of creatinine due to crizotinib treatment also might result in the increase of CYFRA21-1 concentration in the course of treatment. However, renal functions assessed by serum creatinine concentrations were normal in all of our patients and were not impaired by crizotinib treatment.

Lung cancers are sometimes heterogenous (e.g., adenosquamous cell carcinomas). In general, paradoxical increases in CYFRA21-1 concentrations could suggest progression of a component that is ALK-negative and resistant to crizotinib. However, no such occult tumors were detected in any of the present cases, and decreasing or discontinuing crizotinib resulted in a rapid decrease in CYFRA21-1.

Conclusions

Although the frequency and precise mechanisms of crizotinib-induced CYFRA21-1 elevation remain unclear, pulmonologists and oncologists should be aware of the novel phenomenon of CYFRA21-1 increasing in association with crizotinib treatment, and need to focus on interpretation of CYFRA21-1 concentrations in monitoring tumor response to crizotinib treatment.

References:

- 1.Ono A, Takahashi T, Mori K, et al. Prognostic impact of serum CYFRA 21-1 in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:354. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park SY, Lee JG, Kim J, et al. Preoperative serum CYFRA 21-1 level as a prognostic factor in surgically treated adenocarcinoma of lung. Lung Cancer. 2013;79:156–60. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cedrés S, Nuñez I, Longo M, et al. Serum tumor markers CEA, CYFRA21-1, and CA-125 are associated with worse prognosis in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Clin Lung Cancer. 2011;12:172–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camidge DR, Bang YJ, Kwak EL, et al. Activity and safety of crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: updated results from a phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1011–19. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70344-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang L, Chen X, Li Y, et al. Declines in serum CYFRA21-1 and carcinoembryonic antigen as predictors of chemotherapy response and survival in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4:243–48. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin XF, Wang XD, Sun DQ, et al. High Serum CEA and CYFRA21-1 Levels after a Two-Cycle Adjuvant Chemotherapy for NSCLC: Possible Poor Prognostic Factors. Cancer Biol Med. 2012;9(4):270–73. doi: 10.7497/j.issn.2095-3941.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bártek J, Bártková J, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, et al. Differential expression of keratin 19 in normal human epithelial tissues revealed by monospecific monoclonal antibodies. Histochem J. 1986;18:565–75. doi: 10.1007/BF01675198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szturmowicz M, Tomkowski W, Fijalkowska A, et al. Diagnostic utility of CYFRA 21-1 and CEA assays in pericardial fluid for the recognition of neo-plastic pericarditis. Int J Biol Markers. 2005;20:43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama M, Satoh H, Ishikawa H, et al. Cytokeratin 19 fragment in patients with nonmalignant respiratory diseases. Chest. 2003;123:2001–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.6.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothenstein JM, Letarte N. Managing treatment-related adverse events associated with Alk inhibitors. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:19–26. doi: 10.3747/co.21.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe N, Nakahara Y, Taniguchi H, et al. Crizotinib-induced acute interstitial lung disease in a patient with EML4-ALK positive non-small cell lung cancer and chronic interstitial pneumonia. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:158–60. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.802838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]