Abstract

Patient: Female, 42

Final Diagnosis: Insulinoma

Symptoms: Blurring of vision • dizziness

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Endocrinology and Metabolic

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Although fasting hypoglycemia has historically been considered the hallmark of insulinoma, postprandial hypoglycemia has also been occasionally reported as the predominant feature. We report a rare case of an insulinoma diagnosed in an individual presenting exclusively with postprandial hypoglycemia without fasting hypoglycemia.

Case Report:

A 47-year-old woman with medical history of migraine, depression, hypercholesterolemia, iron deficiency anemia, and peptic ulcer disease presented with complaints of frequent episodes of dizziness, blurring of vision, and anxiety over the past 4 months. These episodes usually occurred 1–2 hours after eating and resolved with ingestion of sugary foods. Home glucometer readings during typical symptoms were 47–64 mg/dL. Physical exam revealed a healthy-appearing middle-aged female with BMI of 28. Laboratory data after an overnight fast showed serum blood glucose 77mg/dL and AM cortisol 9.6 (5–25 µg/dl). Hemoglobin A1C, thyroid function tests, IGF-1, liver function tests, and kidney function were in normal range. She was instructed to bring a typical meal to the clinic for monitoring of postprandial glucose levels. Three hours after ingestion of the meal, she developed typical adrenergic symptoms during which laboratory analysis revealed a serum glucose level of 44 mg/dL, C-peptide of 2.9 (0.8–3.1ng/ml), insulin level of 32 (0–17 µIU/lt), negative sulfonylurea screen, and insulin antibodies. She was treated with 15 grams of oral glucose, which alleviated her symptoms. Medical therapy with acarbose was attempted, but did not lead to significant reduction in hypoglycemic events. CT abdomen/pelvis confirmed the presence of a tumor in the tail of the pancreas. The patient subsequently underwent partial pancreatectomy, splenectomy, and lymph node resection, with resolution of symptoms. Histopathological analysis confirmed insulinoma.

Conclusions:

We present a rare case of an insulinoma in the setting of verified postprandial hypoglycemia with elevated insulin and C-peptide levels. Although insulinomas typically present with fasting hypoglycemia, it is important to consider insulinoma in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting exclusively with postprandial hypoglycemia.

MeSH Keywords: C-Peptide, Hypoglycemia, Insulinoma

Background

Insulinoma is a rare tumor of the pancreas, with an estimated incidence of 0.4 per 100 000 person-years [1]. It is more common in females, with median age of 47 years at diagnosis [1]. Historically, fasting hypoglycemia has been considered the primary presenting feature of insulinoma. However, rare cases of insulinoma presenting exclusively with postprandial hypoglycemia have come to light. A recent retrospective review from the Mayo Clinic showed that a total of 6% of patients with insulinoma presented only with postprandial-related symptoms [2]. Here, we report a rare case of insulinoma diagnosed in an individual presenting with postprandial hypoglycemia without evidence of fasting hypoglycemia.

Case Report

A 47-year-old female presented to her primary care physician with complaints of frequent episodes of lightheadedness, blurring of vision, dizziness, and anxiety of 4-months duration. These episodes usually occurred 1–2 hours after eating. Her symptoms were relieved by ingestion of sugary foods. Her internist provided her with a glucometer to monitor her blood sugars and referred her to Endocrinology for further work-up.

The patient denied any prior history of type 2 diabetes or gastric bypass surgery, and had no immediate family members with diabetes. She appeared healthy and physical exam results were unremarkable. Review of her glucometer revealed the following finger-stick readings: morning glucose levels ranging 77–100 mg/dl and afternoon and evening levels as low as 47–56 mg/dL. She denied any symptoms in the fasting state. Her medication list was reviewed and did not reveal any potential hypoglycemic agents.

The patient returned to the clinic for blood tests in the fasting state. She was asymptomatic at the time of blood draw. Fasting serum glucose was 77 mg/dl, AM cortisol 9.6 (5–25 µg/dL), thyroid function test results were normal with TSH 1.23 (0.4–4.5 mIU/L), Free T4 1.26 (0.80–2 ng/dL) and IGF-1 at 178 (52–328 ng/mL). Insulin antibodies were negative. HbA1c was 5.4 (4.7–6.4%). Liver and kidney function test results were normal.

The patient was instructed to return to the clinic for supervision after consumption of a mixed meal that typically provoked her symptoms. She developed adrenergic symptoms about 3 hours after ingestion of the meal and point-of-care testing revealed a glucose level of 52 mg/dl. Blood samples were drawn immediately, and she was subsequently treated with 15 grams of oral carbohydrate, which led to rapid resolution of her symptoms. Blood tests measured during the episode (Table 1) yielded a serum blood glucose level of 44 mg/dl, C-peptide of 2.9 ng/mL, and insulin level of 32 µU/mL. Sulfonylurea screen was negative.

Table 1.

Laboratory values.

| LFT | BMP | Endocrine work up | CBC/miscellaneos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein 7.4 (6–8.5 g/dl) | Na 142 (135–145meq/l) | Insulin level 32 (0–17 µiU/lt) | RBC 4.03 (4–5.02 mil/ul) |

| Albumin 4.7 (3.2–4.8 g/dl) | K 4.3 (3.5–5 meq/l) | C peptide 2.9 (0.83.1 ng/ml) | Differentials N% 59.5, L% 31.9, E%1 |

| Total bilirubin 0.4 (0.2–1.2 mg/dl) | HCO3 28 (24–30 meq/l) | Proinsulin 43.6 (3–20 pmol/l) | Hb 12.9 (12–16 g/dl) |

| Direct bilirubin 0.1 (<0.3 mg/dl) | Cl 105 (98–108 meq/l) | IgF1 178 (52–328 ng/ml) | Hct 37.2 (42–51%) |

| AST 16 (9–36 U/L) | BUN 10 (6–20 mg/dl) | Cortisol 9.6 (5–25 mu gm/dl) | WBC 5.9 (4.8–10.8 K/Ul) |

| ALT 15 (5–40 U/L) | Cr. 0.7 (0.5–1.5mg/dl) | TSH 1.23 (0.4–4.5 Miu/l) | Platelets 217 (150–400 k/Ul |

| Alk Phos 67 (42–98) unit/l | Ca 9.4 (8.5–10.5 mg/dl | Free T4 1.25 (0.80–2.0 ng/dl) | |

| Glucose 44 mg/dl HbA1c 5.4 (4.7–6.4) |

|||

| LDL cholestrol 175 (<160 mg/dl) Total cholesterol 246 (152–240 mg/dl) |

A preliminary diagnosis of postprandial hypoglycemia was made. Initial imaging with an abdominal ultrasound was unrevealing. The patient was advised to eat small, frequent meals during the day, to avoid sugary substances, and to increase fat and fiber content in her diet. She was also placed on a daily regimen of acarbose as medical therapy to prevent recurrent hypoglycemia.

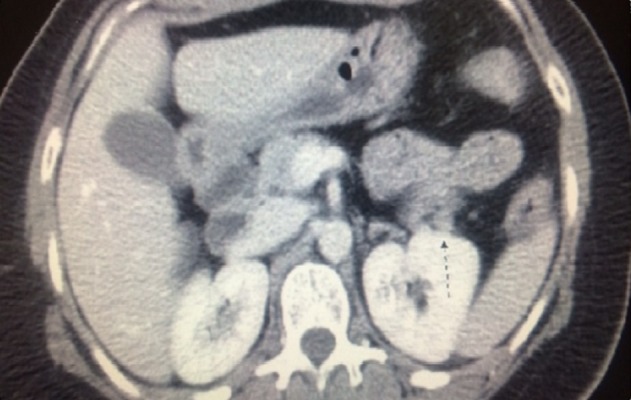

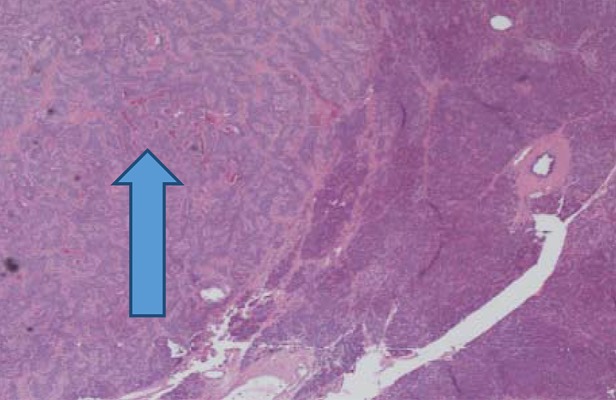

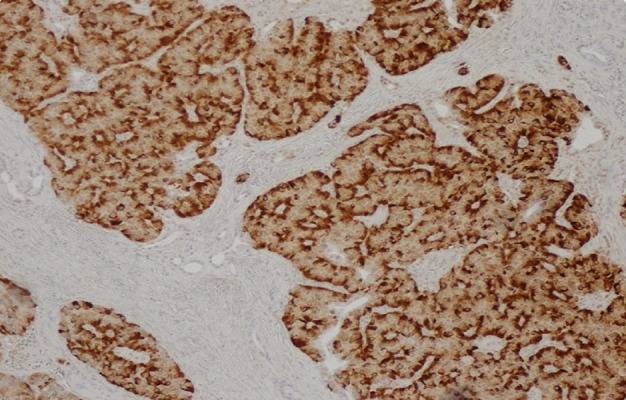

Despite titration of acarbose to 75 mg orally 3 times a day, the patient continued to have debilitating hypoglycemic episodes several times a week. Further imaging was pursued to rule out the possibility of an insulinoma. CT of abdomen/pelvis showed a “small hyper-enhancing focus in the tail of the pancreas, measuring approximately 12 mm in diameter” (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasound did not visualize a lesion that could be biopsied. She was referred to endocrine surgery and subsequently underwent laparoscopic partial pancreatectomy and splenectomy. Pathology report revealed 3 tumors in the pancreatic body and tail measuring 0.8 cm, 1 cm, and 1.2 cm in greatest dimension. Histologically, the tumors were neuroendocrine, well-differentiated, and stained positive for synaptophysin, insulin, CD56, AE1/3, Ki 67.2%, and chromogranin (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

CT Abdomen with contrast showing Insulinoma.

Figure 2.

Histopathological slides showing insulinoma (arrow head showing Insulinoma tissue).

Figure 3.

Insulin stain used for insulinoma.

Therefore, the final diagnosis of insulinoma was made. After surgery, the patient’s glucose levels remained in normal range and she did not complain of further hypoglycemic episodes during the subsequent 3-month follow-up period.

Discussion

Hypoglycemic disorders are confirmed after Whipple’s triad has been established: symptoms of hypoglycemia in the presence of low blood glucose levels and resolution of symptoms on correction of hypoglycemia. Sympathoadrenal and neurological symptoms like tremor and confusion may be highly suggestive of hypoglycemia, but they cannot be ascribed to hypoglycemia unless the serum glucose is verified to be low at the same time as the symptoms.

To obtain documentation of hypoglycemia, it may be necessary to perform provocative testing such as a 72-hour fast, mixed-meal test, or supervised exercise to simulate hypoglycemic conditions if a spontaneous episode is not observed [3]. The purpose of these studies is to recreate the environment in which symptomatic hypoglycemia is likely to occur and to collect samples for glucose, insulin, and C-peptide testing during the observation period. Based on our patient’s reliable report of postprandial symptoms, we performed outpatient mixed-meal testing, which yielded serum glucose <55 gm/dL during a typical symptomatic episode and provided biochemical confirmation of hypoglycemia. At a serum glucose <55 gm/dL, endogenous insulin production should be completely suppressed; thus, her detectable C-peptide and insulin levels and negative screening for hypoglycemic agents supported the presence of inappropriate endogenous hyperinsulinemia.

Once hypoglycemia has been documented, further workup should be pursued to determine the etiology of the disorder. Classically, hypoglycemia in non-diabetic, healthy-appearing patients has been differentiated as either occurring in the fasting or postprandial state. Fasting hypoglycemia raises a high degree of suspicion for insulinoma after factitious hypoglycemia has been excluded. On the other hand, the differential for postprandial hypoglycemia can encompass factitious hypoglycemia, non-insulinoma pancreatogenous hypoglycemia (or nesidioblastosis), early latent type 2 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune diabetes, and, much less commonly, insulinoma [4]. In our patient, an HbA1c of 5.4 made overt type 2 diabetes mellitus unlikely. Serum insulin antibodies and sulfonylurea screen were negative, thus ruling out the possibility of autoimmune or factitious hypoglycemia. A rare genetic etiology of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia is familial adult-onset hyperinsulinemia due to an activating glucokinase mutation [5]; however, our patient did not have any family history of hypoglycemia to suggest a genetic basis for her disorder. Type B insulin resistance is a rare syndrome associated with autoimmune diseases and characterized by the presence of autoantibodies against the insulin receptor. Patients typically present with hyperglycemia and severe hyperinsulinemia at onset, but at later stages can experience hypoglycemia, possibly due to inhibition of insulin degradation [6].

Due to the absence of fasting hypoglycemia, our initial suspicion for insulinoma was quite low and we attributed our patient’s hypoglycemia to early latent type 2 DM or possibly nesidioblastosis. In the early stages of type 2 DM, there can be a delay in initial insulin production after a carbohydrate-heavy meal, resulting in subsequent insulin/glucose mismatch and late hypoglycemia. The 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test may be useful for diagnosis of impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 DM when fasting serum glucose and HbA1c are normal. Nesidioblastosis is a histopathological term used to describe pancreatic islet-cell hypertrophy and is functionally associated with hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia, a condition observed both spontaneously and after bariatric surgery [7]. Management of recurrent postprandial hypoglycemia for both conditions may involve dietary modifications, such as reducing carbohydrate intake, or medical therapy with an α-glucosidase inhibitor (e.g., acarbose), which decreases intestinal glycosidase absorption.

Interestingly, our patient never complained of symptoms in the fasting state and several glucose measurements after overnight 12-hour fasting were always in the normal range. Although we did not perform a formal 72-hour fasting study, in hindsight it is possible that she might not have been able to tolerate such a prolonged period of fasting. Regardless, the persistent and refractory nature of our patient’s postprandial complaints prompted us to question our initial exclusion of insulinoma and to pursue further localization studies. Conventional imaging to localize insulinoma includes transabdominal ultrasound, high-resolution CT, and MRI. Occasionally, when non-invasive imaging studies fail to localize the tumor, unconventional modalities such endoscopic ultrasound, octreotide scintigraphy, and arterial calcium stimulation test may be needed to localize insulinoma and guide surgical treatment [8,9]. In our case, high-resolution CT revealed a suspicious pancreatic lesion that was confirmed as insulinoma after partial pancreatectomy.

It is unclear why our patient with insulinoma presented in an atypical fashion with solely postprandial hypoglycemia, but we hypothesize that there could be underlying molecular differences in tumor biology that have not yet been elucidated. Contrary to our patient’s female sex, a case series by the Mayo Clinic reported a slight male predominance of the 6% of patients with exclusive postprandial hypoglycemia and found no other common clinical features [2]. The authors also noted an increase in the frequency of reported postprandial symptoms over time by quartile, from 2% (1987–1992) to 10% (2003–2007) [2]. Environmental factors and changes in dietary habits over time may be responsible for this evolution in the clinical presentation of patients with insulinoma. Our patient had been consuming a diet high in refined sugars and carbohydrates, which might have provoked an exaggerated postprandial response from an insulinoma that otherwise would have remained clinically silent.

Conclusions

Insulinoma is most commonly associated with fasting hypoglycemia and in some cases postprandial hypoglycemia and fasting hypoglycemia, but it is unusual for insulinoma to present exclusively with postprandial hypoglycemia. However, it is important not to exclude insulinoma in the workup of a patient with postprandial hypoglycemia and normal fasting studies, as it accounts for a small but significant percentage of cases.

Reference:

- 1.Service FJ, McMahon MM, O’Brien PC, Ballard DJ. Functioning insulinoma – incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival of patients: a 60-year study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66(7):711–19. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Placzkowski KA, Vella A, Thompson GB, et al. Secular trends in the presentation and management of functioning insulinoma at the Mayo Clinic, 1987–2007. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(4):1069–73. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Service FJ, Natt N. The prolonged fast. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(11):3973–74. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.11.6934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchigata Y, Hirata Y, Omori Y. Hypoglycemia due to insulin autoantibody. Am J Med. 1993;94(5):556–57. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90101-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Challis BG, Harris J, Sleigh A, et al. Familial adult onset hyperinsulinism due to an activating glucokinase mutation: implications for pharmacological glucokinase activation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014 doi: 10.1111/cen.12517. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arioglu E, Andewelt A, Diabo C, et al. Clinical course of the syndrome of autoantibodies to the insulin receptor (type B insulin resistance): a 28-year perspective. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:87–100. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Service GJ, Thompson GB, Service FJ, et al. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia with nesidioblastosis after gastric-bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:249–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okabayashi T, Shima Y, Sumiyoshi T, et al. Diagnosis and management of insulinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(6):829–37. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doppman JL, Miller DL, Chang R, et al. Insulinomas: localization with selective intraarterial injection of calcium. Radiology. 1991;178(1):237–41. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.1.1984311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]