Abstract

In recent years it has become evident that gap junctions and hemichannels, in concert with extracellular ATP and purinergic receptors, play key roles in several physiological processes and pathological conditions. However, only recently has their importance in infectious diseases been explored, likely because early reports indicated that connexin containing channels were completely inactivated under inflammatory conditions, and therefore no further research was performed. However, recent evidence indicates that several infectious agents take advantage of these communication systems to enhance inflammation and apoptosis, as well as to participate in the infectious cycle of several pathogens. In the current review, we will discuss the role of these channels/receptors in the pathogenesis of several infectious diseases and the possibilities of generating novel therapeutic approaches to reduce or prevent these diseases.

Keywords: Virus, bacteria, purinergic, gap junctions, HIV, CMV, AIDS, reservoirs, pathogen

General introduction

Gap junction (GJ) channels are formed by the docking of two hemichannels, each contributed by one cell. Hemichannels consist of hexamers of homologous subunit proteins, termed connexins (Cxs), that connect the cytoplasm of adjacent cells [1, 2]. In addition, it was shown that unapposed hemichannels (uHC), before their cell-to-cell docking to form GJ, are also open on cell surface, allowing exchange of small factors between the cytoplasm and the extracellular environment. In addition to the connexin family, pannexin also can form uHCs. Both types of channels, GJ and uHC (connexin and pannexin containing), have an internal pore of approximately 12 A°, allowing ions and intracellular messengers up to ~1 kDa in molecular mass to diffuse between connected cells or from the cytoplasm into the extracellular space [1, 2]. The diffusion of these second messengers results in the coordination of multiple physiological functions [2].

ATP is a second messenger exchanged by GJ and uHC and is the main purinergic messenger. ATP is realeased into the extracellular space as a neurotransmitter, but also in conditions of apoptosis and inflammation by exocytosis, transporters, and opening of uHC. Once released into the extracellular space, ATP binds to purinergic receptors and is degraded by ectonucleotidases to produce ADP, AMP, and adenosine. These molecules activate specific purinergic and adenosine receptors. Purinergic receptors are divided into metabotropic (adenosine and purinergic P2Y) and ionotropic receptors (purinergic P2X). Adenosine receptors, also named P1 receptors, are seven transmembrane metabotropic receptors coupled to Gi, Gs and Go proteins. P2 receptors are divided into P2X and P2Y receptors and are activated by ATP, ADP, and UTP. P2X receptors are ATP –gated cationic channels and are associated with uHC that upon opening provide the source of intracellular ATP for purinergic receptor activation. P2Y receptors are activated by ATP, ADP, UTP, and UDP, and several subtypes of these receptors work together with uHC providing/releasing ATP as a ligand.

Here, we will review the mechanism by which GJ and uHC in concert with purinergic receptors and extracellular ATP (or subproduct of its degradation) participate in several infectious diseases and on the potential of these channels to be used as therapeutic targets to reduce or prevent infectious diseases.

Inflammation and down regulation of Connexin containing channels: Historic perspective

Several publications in the 1990’s demonstrated that LPS and inflammation decreased gap junctional communication (GJC) and Cx expression in liver and heart [3–8]. In addition, experiments in brain associated damage such as ischemia/reperfusion, cancer and inflammatory diseases, also indicated that inflammation/damage reduced GJC and Cx expression [9, 10]. Recent reports examining several pathogens including Bordetella pertussis, Helicobacter pylori, and several viruses also supported the idea that infection with several pathogens resulted in the total shutdown of Cx mediated communication [11]. However, at the same time several manuscripts described unusual results of increased expression of Cx43 in inflammatory conditions in liver, kidney and lungs [12–15], suggesting that not all Cxs were affected equally by inflammation/damage. Later studies indicated that Cxs are expressed in leukocytes [13], microglia [16–19], polymorphonuclear cells [20], monocyte/macrophages [21], T cells [22], and Kupffer cells [14, 15] under inflammatory conditions to coordinate inflammation and immune response. These observations suggest that parenchymal Cxs are negatively affected by inflammation/damage, but immune cells that normally do not express Cxs are prone to express and form functional channels in inflammatory conditions. Only recently, it has been reported that particular pathogens such as Shigella, Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa use or increased this communication system to enhance associated inflammation or to participate in the infectious cycle (see review by [11]). Thus, a better understanding of the role of these channels and their association with purinergic receptors and uHC in physiological and pathological conditions it was required.

Purinergic receptors and hemichannels: working together in physiological and pathological conditions

Purinergic receptors participate in several physiological events such as vasodilation, pain, neuroprotection, cell differentiation, migration, muscle contraction, T cell differentiation, platelet aggregation, inflammation, autocrine and paracrine signaling, neurotransmission, apoptosis and several immune responses [23]. Due to their importance in physiological processes, alterations in expression and function of these receptors result in pathological conditions, including epilepsy, excessive pain, hypertension, and several infectious diseases.

Response to infectious agents or inflammation can be summarized in several steps including initial damage or infection, release of chemoattractants, recruitment of leukocytes, transmigration and subsequent local inflammation/clearance of the agent or damaged area. Normally in the blood, erythrocytes circulate in the periphery to exchange nutrients and oxygen/CO2. In inflammatory conditions, hemodynamics change and circulating white cells interact with the endothelial surface in a process called margination. After this change in localization, leukocytes become adherent and start to transmigrate into areas of damage or infection by traversing the endothelial cells and basement membrane. During all these processes the presence and participation of Cx and Panx containing channels, extracellular ATP, and purinergic receptors has been described as discussed below.

The role of extracellular ATP, uHC, and purinergic receptors in inflammation and infectious disease has only recently been examined and recognized. Purinergic receptors and uHC are highly expressed in immune cells and play a key role in migration as well as killing of intracellular pathogens. The best examined purinergic receptor is P2X7 due to its early identification and relatively easy evaluation of gating due its similar pore size as compared to uHC. P2X7 is widely expressed in hematopoietic and nervous systems and participates in physiological and pathological processes in concert with uHC. Opening of both P2X7 and uHC normally is low to undetectable mainly due to high concentrations of calcium, magnesium and the lack of inflammatory signals (see [11] for an excellent review about regulation of these channels). However, upon opening of uHC, intracellular signaling molecules such as ATP, NADH, PGE2, and ions are released into the extracellular space, resulting in activation of several surface receptors, including purinergic receptors.

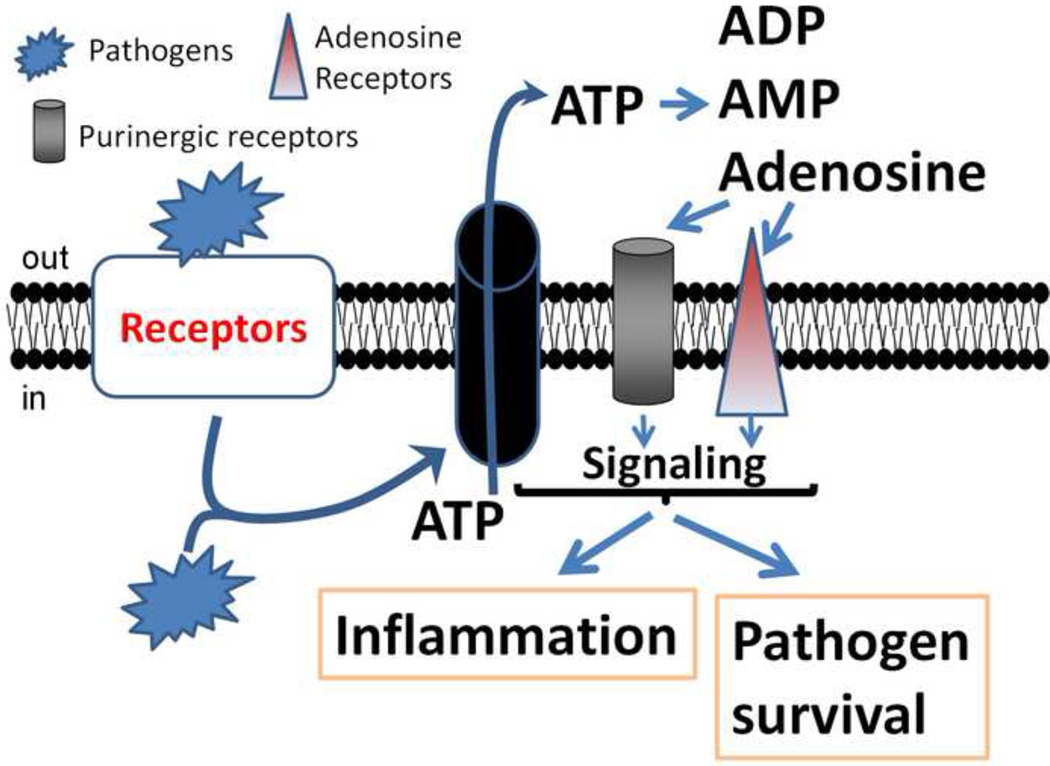

Several infectious agents have evolved to block or overactivate these communication systems by releasing several enzymes that modulate extracellular concentrations of ATP, such as adenylate kinase, ATPase, and 5’-nucleotidase [24–27], altering the communication between uHC and purinergic receptors. Some of these pathogens are Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Shigella flexneri, Yersinia enterocolitica, Staphylococcus aureus and several viruses (see details below). Another mechanism of pathogen escape is by direct regulation of the expression and function of purinergic receptors as described for cytomegalovirus [28]. Lastly, several pathogens can regulate ATP secretion as described for Plasmodium falciparum or P. berghei [29, 30]. It has been proposed that the mechanism by which the anti-malarial drug, mefloquine, works is by inhibiting uHC and purinergic receptors [31], altering infectivity and disease progression, suggesting a key role of these channels in the pathogenesis of malaria. In addition, several pathogens such as HIV, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), P. auruginosa, S. aureus and Escherichia coli, as well as Streptococcus pneumonia, Clostridium, Yersinia enterocolitica and Shigella flexneri use connexin and pannexin containing channels to spread infection, inflammation and toxicity (see details in [11]). Thus, several potential mechanisms involving the interaction of uHC, ATP and purinergic receptors are “hijacked” by pathogens to survive, replicate and enhance inflammation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed mechanism by which pathogens use extracellular ATP, uHC and purinergic receptor in the context of infectious diseases. Extracellular and intracellular pathogens bind or activate signaling related to these receptors, leading to ATP release through uHC containing connexin or pannexin proteins. Extracellular ATP binds to specific purinergic receptors, activating calcium influx and G coupled proteins that facilitate intracellular signaling. This signaling participates in inflammation and several pathogens life cycles. In addition, upon release of ATP, several extracellular enzymes degrade ATP into ADP, AMP, and adenosine, which further activate other purinergic and adenosine receptors that participate in inflammation and pathogenesis.

Cytokine production and inflammation

The best described mechanisms of participation of purinergic receptors and uHC in disease progression are described for cellular migration of immune cells, detection of apoptotic cells, and secretion of inflammatory factors. For example, processing and release of IL-1β and IL-18 is mediated by secretion of ATP, activation of P2X7, opening of uHC and elevated release of intracellular ATP [32–36]. In contrast, chronic release of ATP or inflammation activates cells of the monocyte/macrophage lineage to secrete antiinflammatory cytokines including IL-10 and IL-1β receptor antagonist to reduce inflammation and causes development of a Th2 response.

As indicated above, a key element in inflammation is the synthesis, processing and release of IL-1β. This cytokine is produced as two isoforms, pro-IL-1α and pro-IL-1β, which are subsequently cleaved by interleukin-converting enzyme (ICE), also known as caspase-1, to produce the mature isoforms. However, some pathogens like rhinoviruses evolved to induce IL-1β secretion without a P2X7 component [37], suggesting that some viruses can skip the activation of purinergic receptors to trigger inflammation. In addition to this cytokine, IL-18, also known as interferon-γ inducing factor, is also formed by the processing of pro-IL-18 by ICE. As discussed later on, a P2X7 polymorphism produces significantly less IL-18 when stimulated by ATP, suggesting a key role in immune response and inflammation. This individual to individual genetic variability, especially in P2X7 receptors, is essential to understanding differential responses of particular populations to several pathogens. In addition, polymorphic changes in uHC have been described and may contribute to this variability in immune responses. For example, Cx37 C1019T polymorphism contributes to Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with gastric cancer [38]. These observations suggest that genetic alterations in these channels and receptors could alter inflammation and susceptibility to several infectious agents.

Inflammasome activation requires ATP-purinergic receptors to trigger shedding of microvesicles [34], TLR-4 activation [39], and apoptosis [40]. Also, ATP impairs IL-10 expression of soluble and membrane bound HLA-G Ag in human monocytes [41], suggesting that ATP or pathogens altering ATP secretion/stability could alter immune responses mediated by the immunosuppressive activity of IL-10. ATP also inhibits IL-12 and IL-23 expression in human dendritic cells by a cAMP dependent mechanism [42], suggesting that ATP also plays a key role in immunosuppression. In addition, IL-10 suppresses IL-2 secretion [43] by interfering with CD28 induced activation [44]. Thus, by targeting uHC, extracellular ATP, and purinergic receptors some pathogens may alter NFAT T cell activation, resulting in anergy, senescence and apoptosis [45, 46].

Another critical event in inflammation and infection is leukocyte migration into areas of damage. Most leukocytes migrate in response to chemoattractants including chemokines, lipids (e.g. lysophosphosphatidylchloline released by apoptotic cells) and nucleotides (e.g. ATP and UTP) [47, 48]. Several lines of evidence indicate that uHC and purinergic receptors participate in these events. Migration of human monocytes in response to CCL2/MCP-1 across the blood brain barrier is dependent on Cx43 containing gap junction channels, but we cannot discard the participation of uHC [21]. Further, Cx43 containing channels and purinergic receptors modulate neutrophil recruitment/activation. Subsets of CD4+ T cells express Cx43 and form functional GJ with macrophages [22, 49, 50]. MCP-1/CCL2 synthesis and release in rat alveolar and peritoneal macrophages is P2Y2 dependent [51]. Thus, leukocyte migration is regulated by purinergic receptors, ATP, and uHC during all stages of inflammation. Our data indicate that several chemokines including RANTES, MIPs, and SDF-1 cause transient opening of pannexin-1 uHC in human leukocytes [52]. We propose that this transient uHC opening is associated with cellular activation and migration, but further studies are required to test this hypothesis.

In early apoptosis, release of nucleotides occurs by opening of pannexin-1 uHC. During later events of apoptosis this channel is targeted by caspase-3 and -7, proteases that cleave an intracellular portion of the channel, contributing further to the apoptotic process by disrupting the gating of the channel [48, 53]. Thus, during the apoptotic process uHC, ATP, and purinergic receptors participate as regulators of chemoattraction as well as key regulators of recognition and clearance of apoptotic cells. In addition, there are several reports that describe the potential of purinergic receptors and/or uHC to interact with intracellular adaptor proteins, such as laminin, actin, actinin, integrins, kinases and phosphatases [54, 55], to amplify inflammation and damage but the significance of these interactions is still unclear. All these areas are under active investigation.

Tuberculosis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the infectious agent that causes tuberculosis in humans. In this infectious disease, activation of P2X7 receptors play a key role in inducing intracellular killing of this bacterium inside of macrophages by a calcium dependent mechanism that induces phagosome-lysosome fusion [56–58]. This response to mycobacterial infection is dependent on polymorphic changes in the P2X7 receptor [59]. In addition, several splicing variants of P2X7 have been described as having different agonist dependency and interaction with pannexin-1 uHC [60], suggesting that these changes may also contribute to the pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Pannexin-1 uHC also has several genetic isoforms [61], suggesting that the interaction of this complex between purinergic and uHC is dependent on the genetic background of each individual, providing additional risk and protective host factors against tuberculosis. Further, the allele 1513C of P2X7 is a risk factor in the development of extrapulmonary and pulmonary tuberculosis in several ethnic populations, including north Indian, Mexican, Russian, and Turkish [62]. In contrast, P2X7 polymorphism in position -762 is protective against tuberculosis in an Asian-Indian cohort [63].

Similar effects of extracellular ATP and purinergic receptors have been described in clearance and immune response to Chlamydia by a phospho-lipase D dependent mechanism, resulting in 70–90% elimination of this intracellular bacterium in macrophages [64–66]. However, several pathogens can “hijack” these systems. For example, Chlamydia infected macrophages are protected from apoptosis while uninfected cells are still susceptible to cell death [65]. Similar survival mechanisms were observed in HIV infected cells to generate reservoirs to perpetuate replication and pathogen survival [67–69].

Shigella and Yersinia

These are gram negative bacteria that are transmitted mainly by the fecaloral route, resulting in diarrhea and fever by a mechanism involving invasion and replication in the colon with epithelial dysfunction. Infection of epithelial cells with S. flexneri results in Cx43, 32 and 26 uHC activity that supports invasion, by actin and PLC dependent mechanisms [70], resulting in ATP release that helps bacterial invasion and replication [70, 71]. In addition, infected cells induce a bystander activation of uninfected cells resulting in secretion of IL-18 by a gap junction dependent mechanism [72]. It is critical to mention that secretion of IL-18 is also dependent on purinergic receptor activation as described above. Interestingly, the mechanism of Shigella flexneri uptake was dependent on micropodial extensions from the cell surface (like filopodiums) allowing complexes of proteins in the tips of these processes to bind the bacteria by an ATP and Cx dependent mechanism. This local release of ATP activates Erk1/2 and results in actin retrograde flow of these processes that are in contact with the bacteria. In cases of infection with Yersinia enterocolitica, opening of Cx43 uHC has been described by a mechanism dependent on channel phosphorylation [73]. Thus, both entero-pathogens utilize the complex interactions of uHC, ATP, and purinergic receptors, as well as GJ channels to invade, replicate and amplify dysfunction in the host.

Staphyloccocus aureus

This gram positive bacterium lives in every healthy human. Due to the wide use of antibiotics, methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA) has emerged. Mainly found in hospitals and several sensitive communities, a key pathogenic component of this bacterium is the peptidoglycan present in the bacterial cell wall. Peptidoglycan reduces Cx expression (protein and mRNA) and functional gap junction coupling in astrocytes by a mechanism involving p38 MAPK [74]. Studies in brain slices also demonstrated down regulation of gap junctional communication in response to peptidoglycan [75]. However, despite the reduction in GJC, increased expression of Cx43 and Cx30 as well as opening of uHC has been reported [75, 76]. In contrast, peptidoglycan induces expression of Cxs that result in functional gap junction communication in microglia, suggesting that depending of the cell type and type of the insult, these channels could participate in both physiological and pathological conditions.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV)

This usually harmless virus is a double-stranded DNA virus and member of the herpes virus family. Around 50–80% of the population is infected. Viral transmission occurs by contact with saliva, urine, breast milk and other fluids. 0.2 to 1.2% of all births are CMV contaminated and no treatment is available. However, congenital CMV infection is a major public health problem that results in permanent problems such as hearing loss, and mental/developmental disabilities. It is clear that hearing loss is attributable to congenital CMV infection and is associated with heterozygote Cx26 mutations as compared to congenital CMV infected children without hearing loss [77], suggesting that potential genetic changes induced by CMV infection may alter Cx26 channels, including uHC and GJ. Further, dysfunction of Cx26 uHC, GJ, and purinergic receptors has been associated with mild to severe hearing/deafness [78, 79], suggesting a potential link between both conditions.

CMV infection is a strong promoter of degradation of Cx43 and disruption of GJC [80]. Central and peripheral nervous system development is highly dependent in Cx43 GJ and perhaps uHC [81, 82], and we propose that CMV infection may compromise this development [83]. We propose that CMV alters Cx43 trafficking and function, resulting in CNS compromise often observed in CMV infected children. This is a new area of research that requires priority due to the significant contribution of the virus to nervous system and hearing problems.

Other viral and bacterial infections

As indicated above both viral and bacterial infection can reduce communication between uHC, GJ, purinergic receptors, and alter secretion of ATP. Swine Influenza viral infection down-regulates endothelial Cx43 expression by increased degradation in a ERK dependent manner [84]. Borna virus also down regulates Cx36 in specific CNS cell types [85–87]. Influenza during pregnancy alters development of the brain of the fetus, suggesting that viruses can impact neuronal development by affecting GJs [88] possibly by a similar mechanism as proposed for CMV. Studies in Vero cells demonstrated that infection with Herpes Simplex Virus-2 (HSV-2) and treatment with the antiviral agent, acyclovir, down-regulated GJ channels and Cxs expression [89–91]. It was reported that an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation by HSV-2 and Rous sarcoma virus leads to an inhibition of GJ and Cx43 expression [92–94]. Bovine papillomavirus type 4 E8, when bound to ductin, causes loss of GJ between primary fibroblasts [95, 96]. As indicated above most viruses reduced communication and expression of these channels/receptors contributing to inflammation and parenchymal dysfunction.

HIV pathogenesis

HIV is a retrovirus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition that mainly attacks the immune system allowing opportunistic infections, cancer and aging related diseases to rise due to lack of an effective immune system. Normally, HIV infects a variety of immune and non-immune cells, including CD4+ T cells, macrophages, microglia, and astrocytes.

Our results in HIV CNS infection indicate that Cx containing channels, gap junctions and uHC play a key role in amplification of inflammation and apoptosis. In the CNS, microglial cell and perivascular macrophages are the predominant cell types infected by HIV [97, 98]. However, a small population of HIV infected astrocytes has been detected [98–106]. The importance of these few infected astrocytes in the pathogenesis of NeuroAIDS has not been examined extensively. Our data indicates that astrocytes are minimally infected by HIV (5–8%), but despite this low infection, HIV uses GJ to spread toxicity and inflammation into uninfected surrounding cells, such as astrocytes and endothelial cells of the blood brain barrier [107]. The small number of HIV infected astrocytes resulted in large alterations in glutamate metabolism and CCL2 secretion, supporting the idea that HIV infection of astrocytes is essential for neuronal compromise and leukocyte transmigration, respectively. Interestingly, HIV infected cells are protected from apoptosis by an unknown mechanism [69, 108, 109]. We propose that these surviving cells generate CNS viral reservoirs within the CNS. We recently identified the intracellular signals that mediate these toxic effects as Cytochrome C dependent molecules, including IP3 and intracellular calcium [67].

In addition, we showed that HIV infection of astrocytes results in the opening of Cx43 uHC, secretion of ATP, and inflammation. Opening of Cx43 uHC requires interaction of the virus with an unknown receptor(s) on the membrane of astrocytes. Microarray analysis indicated that dickkopf-1 protein (DKK1, a soluble wnt pathway inhibitor) mediates compromise of neuronal processes in neurons mediated by HIV infection of astrocytes [110]. Previous to our work, DKK1 also was identified as a key regulator of IFN-γ enhancement of HIV replication and reactivation in astrocytes [111], suggesting that DKK1 also plays a role in HIV replication in astrocytes. The findings that Cxs participate in the pathogenesis of NeuroAIDS open a new avenue of investigation to study the mechanisms by which HIV “hijacks” this communication system, GJ and uHC, to spread toxicity, inflammation, and to increase leukocyte transmigration into the CNS, and may suggest novel therapeutic approaches to target NeuroAIDS.

Our data and others indicates that HIV binding to CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages also results in activation of pannexin-1 uHC, release of ATP, and activation of specific purinergic receptors [112–114]. Exposure of CD4+ T lymphocytes to HIV results in the biphasic opening of pannexin-1 uHC: early (5–15 min) during the interaction of the virus with CD4 and CCR5 or CXCR4, depending of the viral strain used and late, during the release of new virions into the medium (18 to 24 h). Blocking pannexin-1 uHC totally abolished viral replication. Experiments in human macrophages also indicate that HIV infection requires secretion of ATP and activation of purinergic receptors. We demonstrated that P2X1 receptors are essential for HIV entry into macrophages. However, we did not identify where in the viral cell cycle, P2X7 and P2Y1 are regulating replication. In addition, activation of P2Y2 has been also associated with HIV infection and replication [112].

In contrast, activation of adenosine receptors is protective against HIV tat induced toxicity of neurons [115, 116], suggesting that adenosine may also play an important role in preventing HIV-tat neurotoxicity within the CNS. In addition, activation of adenosine receptors down regulates surface expression of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T lymphocytes [117], suggesting that adenosine is protective against HIV infection. Thus, further studies are required to design new therapeutic approaches to reduce and block HIV infection and replication in immune and CNS cells.

Conclusions and future

The findings that uHC containing pannexins or connexins working in concert with purinergic receptors and extracellular ATP (see Figure 1) still is a poorly explored area and requires further investigation. In addition, it is not surprising that these components are misused by several pathogens that have evolved to take advantage of this system to coordinate infection, replication, and associated inflammation. Several pharmaceutical companies already developed drugs to target several purinergic receptors as well as uHC (probenecid) for different diseases, including vascular dysfunctions and arthritis related diseases. However, we still require specific agonists and antagonists as well as the identification of the mechanisms by which pathogens alter these pathways, in order to design, in an informed manner, novel therapeutic approaches to reduce the devastating consequences of infectious diseases. In contrast, several compounds that blocks purinergic receptors are consumed daily without control as food dyes, including compounds derivate from brilliant blue G and Brilliant Blue FCF that are present in several foods and drinks. The consequences of the ingestion of these blockers is unknown but we can predict that reducing immune activation and elimination of cancer cells, could results in depressed immune response and faster cancer evolution amount several potential diseases affected.

The relatively recent discovery of these complexes between purinergic receptors, extracellular ATP and hemichannels, opens new avenues to understand no only inflammation, but several diseases including pathologies with impaired cellular migration, inflammation, and cell clearance (cancer, regeneration and aging). The implications that several pathogens also “highjacks” these complexes indicates that targeting these proteins also could prevent and reduce infectious processes. Thus, the possibility of targeting these complexes of proteins to prevent and treat infectious diseases emerges as a novel therapeutic form to treat infectious agents.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health grants, MH096625 (to E.A.E) and by funding of the Public Research Institute (PHRI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors had no financial interest.

References

- 1.Bennett MV, Contreras JE, Bukauskas FF, Saez JC. New roles for astrocytes: gap junction hemichannels have something to communicate. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saez JC, Contreras JE, Bukauskas FF, Retamal MA, Bennett MV. Gap junction hemichannels in astrocytes of the CNS. Acta Physiol Scand. 2003;179:9–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez-Cobo M, Gingalewski C, Drujan D, De Maio A. Downregulation of connexin 43 gene expression in rat heart during inflammation. The role of tumour necrosis factor. Cytokine. 1999;11:216–224. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gingalewski C, Wang K, Clemens MG, De Maio A. Posttranscriptional regulation of connexin 32 expression in liver during acute inflammation. J Cell Physiol. 1996;166:461–467. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199602)166:2<461::AID-JCP25>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theodorakis NG, De Maio A. Cx32 mRNA in rat liver: effects of inflammation on poly(A) tail distribution and mRNA degradation. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R1249–R1257. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temme A, Ott T, Dombrowski F, Willecke K. The extent of synchronous initiation and termination of DNA synthesis in regenerating mouse liver is dependent on connexin32 expressing gap junctions. J Hepatol. 2000;32:627–635. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Maio A, Gingalewski C, Theodorakis NG, Clemens MG. Interruption of hepatic gap junctional communication in the rat during inflammation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Shock. 2000;14:53–59. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lidington D, Tyml K, Ouellette Y. Lipopolysaccharide-induced reductions in cellular coupling correlate with tyrosine phosphorylation of connexin 43. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:373–379. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rouach N, Avignone E, Meme W, Koulakoff A, Venance L, Blomstrand F, Giaume C. Gap junctions and connexin expression in the normal and pathological central nervous system. Biol Cell. 2002;94:457–475. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(02)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kielian T. Glial connexins and gap junctions in CNS inflammation and disease. J Neurochem. 2008;106:1000–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05405.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ceelen L, Haesebrouck F, Vanhaecke T, Rogiers V, Vinken M. Modulation of connexin signaling by bacterial pathogens and their toxins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3047–3064. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0737-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez-Cobo M, Gingalewski C, De Maio A. Expression of the connexin 43 gene is increased in the kidneys and the lungs of rats injected with bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Shock. 1998;10:97–102. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jara PI, Boric MP, Saez JC. Leukocytes express connexin 43 after activation with lipopolysaccharide and appear to form gap junctions with endothelial cells after ischemia-reperfusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7011–7015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eugenin EA, Gonzalez HE, Sanchez HA, Branes MC, Saez JC. Inflammatory conditions induce gap junctional communication between rat Kupffer cells both in vivo and in vitro. Cell Immunol. 2007;247:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez HE, Eugenin EA, Garces G, Solis N, Pizarro M, Accatino L, Saez JC. Regulation of hepatic connexins in cholestasis: possible involvement of Kupffer cells and inflammatory mediators. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G991–G1001. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00298.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobrenis K, Chang HY, Pina-Benabou MH, Woodroffe A, Lee SC, Rozental R, Spray DC, Scemes E. Human and mouse microglia express connexin36, and functional gap junctions are formed between rodent microglia and neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:306–315. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez AD, Eugenin EA, Branes MC, Bennett MV, Saez JC. Identification of second messengers that induce expression of functional gap junctions in microglia cultured from newborn rats. Brain Res. 2002;943:191–201. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eugenin EA, Eckardt D, Theis M, Willecke K, Bennett MV, Saez JC. Microglia at brain stab wounds express connexin 43 and in vitro form functional gap junctions after treatment with interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4190–4195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051634298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg S, Md Syed M, Kielian T. Staphylococcus aureus-derived peptidoglycan induces Cx43 expression and functional gap junction intercellular communication in microglia. J Neurochem. 2005;95:475–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Branes MC, Contreras JE, Saez JC. Activation of human polymorphonuclear cells induces formation of functional gap junctions and expression of connexins. Med Sci Monit. 2002;8:BR313–BR323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eugenin EA, Branes MC, Berman JW, Saez JC. TNF-alpha plus IFN-gamma induce connexin43 expression and formation of gap junctions between human monocytes/macrophages that enhance physiological responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:1320–1328. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bermudez-Fajardo A, Yliharsila M, Evans WH, Newby AC, Oviedo-Orta E. CD4+ T lymphocyte subsets express connexin 43 and establish gap junction channel communication with macrophages in vitro. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:608–612. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riteau N, et al. ATP release and purinergic signaling: a common pathway for particle-mediated inflammasome activation. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e403. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaborina O, Li X, Cheng G, Kapatral V, Chakrabarty AM. Secretion of ATP-utilizing enzymes, nucleoside diphosphate kinase and ATPase, by Mycobacterium bovis BCG: sequestration of ATP from macrophage P2Z receptors? Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1333–1343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Punj V, Zaborina O, Dhiman N, Falzari K, Bagdasarian M, Chakrabarty AM. Phagocytic cell killing mediated by secreted cytotoxic factors of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4930–4937. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.4930-4937.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franchi L, Kanneganti TD, Dubyak GR, Nunez G. Differential requirement of P2X7 receptor and intracellular K+ for caspase-1 activation induced by intracellular and extracellular bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18810–18818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paoletti A, Raza SQ, Voisin L, Law F, Pipoli da Fonseca J, Caillet M, Kroemer G, Perfettini JL. Multifaceted roles of purinergic receptors in viral infection. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:1278–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zandberg M, van Son WJ, Harmsen MC, Bakker WW. Infection of human endothelium in vitro by cytomegalovirus causes enhanced expression of purinergic receptors: a potential virus escape mechanism? Transplantation. 2007;84:1343–1347. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000287598.25493.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levano-Garcia J, Dluzewski AR, Markus RP, Garcia CR. Purinergic signalling is involved in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum invasion to red blood cells. Purinergic Signal. 2010;6:365–372. doi: 10.1007/s11302-010-9202-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanneur V, et al. Purinoceptors are involved in the induction of an osmolyte permeability in malaria-infected and oxidized human erythrocytes. FASEB J. 2006;20:133–135. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3371fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iglesias R, Locovei S, Roque A, Alberto AP, Dahl G, Spray DC, Scemes E. P2X7 receptor-Pannexin1 complex: pharmacology and signaling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C752–C760. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00228.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrari D, Pizzirani C, Adinolfi E, Lemoli RM, Curti A, Idzko M, Panther E, Di Virgilio F. The P2X7 receptor: a key player in IL-1 processing and release. J Immunol. 2006;176:3877–3883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang TT, et al. Hirsutella sinensis mycelium suppresses interleukin-1beta and interleukin-18 secretion by inhibiting both canonical and non-canonical inflammasomes. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1374. doi: 10.1038/srep01374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gulinelli S, et al. IL-18 associates to microvesicles shed from human macrophages by a LPS/TLR-4 independent mechanism in response to P2X receptor stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:3334–3345. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dinarello CA. Interleukin-18 and the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27:98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bachmann M, Horn K, Poleganov MA, Paulukat J, Nold M, Pfeilschifter J, Muhl H. Interleukin-18 secretion and Th1-like cytokine responses in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells under the influence of the toll-like receptor-5 ligand flagellin. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:289–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi L, Manthei DM, Guadarrama AG, Lenertz LY, Denlinger LC. Rhinovirus-induced IL-1beta release from bronchial epithelial cells is independent of functional P2X7. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:363–371. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0267OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jing YM, Guo SX, Zhang XP, Sun AJ, Tao F, Qian HX. Association between C1019T polymorphism in the connexin 37 gene and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with gastric cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2363–2367. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.5.2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas LM, Salter RD. Activation of macrophages by P2X7-induced microvesicles from myeloid cells is mediated by phospholipids and is partially dependent on TLR4. J Immunol. 2010;185:3740–3749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qu Y, et al. Pannexin-1 is required for ATP release during apoptosis but not for inflammasome activation. J Immunol. 2011;186:6553–6561. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rizzo R, Ferrari D, Melchiorri L, Stignani M, Gulinelli S, Baricordi OR, Di Virgilio F. Extracellular ATP acting at the P2X7 receptor inhibits secretion of soluble HLA-G from human monocytes. J Immunol. 2009;183:4302–4311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schnurr M, Toy T, Shin A, Wagner M, Cebon J, Maraskovsky E. Extracellular nucleotide signaling by P2 receptors inhibits IL-12 and enhances IL-23 expression in human dendritic cells: a novel role for the cAMP pathway. Blood. 2005;105:1582–1589. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taga K, Cherney B, Tosato G. IL-10 inhibits apoptotic cell death in human T cells starved of IL-2. Int Immunol. 1993;5:1599–1608. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.12.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akdis CA, Joss A, Akdis M, Faith A, Blaser K. A molecular basis for T cell suppression by IL-10: CD28-associated IL-10 receptor inhibits CD28 tyrosine phosphorylation and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase binding. FASEB J. 2000;14:1666–1668. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0874fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woehrle T, Yip L, Manohar M, Sumi Y, Yao Y, Chen Y, Junger WG. Hypertonic stress regulates T cell function via pannexin-1 hemichannels and P2X receptors. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:1181–1189. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0410211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woehrle T, Yip L, Elkhal A, Sumi Y, Chen Y, Yao Y, Insel PA, Junger WG. Pannexin-1 hemichannel-mediated ATP release together with P2X1 and P2X4 receptors regulate T-cell activation at the immune synapse. Blood. 2010;116:3475–3484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lauber K, et al. Apoptotic cells induce migration of phagocytes via caspase-3-mediated release of a lipid attraction signal. Cell. 2003;113:717–730. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elliott MR, et al. Nucleotides released by apoptotic cells act as a find-me signal to promote phagocytic clearance. Nature. 2009;461:282–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarieddine MZ, Scheckenbach KE, Foglia B, Maass K, Garcia I, Kwak BR, Chanson M. Connexin43 modulates neutrophil recruitment to the lung. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:4560–4570. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, et al. Purinergic signaling: a fundamental mechanism in neutrophil activation. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra45. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stokes L, Surprenant A. Purinergic P2Y2 receptors induce increased MCP-1/CCL2 synthesis and release from rat alveolar and peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 2007;179:6016–6023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orellana JA, Velasquez S, Williams DW, Saez JC, Berman JW, Eugenin EA. Pannexin1 hemichannels are critical for HIV infection of human primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:399–407. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0512249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chekeni FB, et al. Pannexin 1 channels mediate 'find-me' signal release and membrane permeability during apoptosis. Nature. 2010;467:863–867. doi: 10.1038/nature09413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim M, Spelta V, Sim J, North RA, Surprenant A. Differential assembly of rat purinergic P2X7 receptor in immune cells of the brain and periphery. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23262–23267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim M, Jiang LH, Wilson HL, North RA, Surprenant A. Proteomic and functional evidence for a P2X7 receptor signalling complex. EMBO J. 2001;20:6347–6358. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lammas DA, Stober C, Harvey CJ, Kendrick N, Panchalingam S, Kumararatne DS. ATP-induced killing of mycobacteria by human macrophages is mediated by purinergic P2Z(P2X7) receptors. Immunity. 1997;7:433–444. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80364-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fairbairn IP, Stober CB, Kumararatne DS, Lammas DA. ATP-mediated killing of intracellular mycobacteria by macrophages is a P2X(7)-dependent process inducing bacterial death by phagosome-lysosome fusion. J Immunol. 2001;167:3300–3307. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kusner DJ, Barton JA. ATP stimulates human macrophages to kill intracellular virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis via calcium-dependent phagosome-lysosome fusion. J Immunol. 2001;167:3308–3315. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernando SL, Saunders BM, Sluyter R, Skarratt KK, Goldberg H, Marks GB, Wiley JS, Britton WJ. A polymorphism in the P2X7 gene increases susceptibility to extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:360–366. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-970OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu XJ, Boumechache M, Robinson LE, Marschall V, Gorecki DC, Masin M, Murrell-Lagnado RD. Splice variants of the P2X7 receptor reveal differential agonist dependence and functional coupling with pannexin-1. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3776–3789. doi: 10.1242/jcs.099374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li S, Tomic M, Stojilkovic SS. Characterization of novel Pannexin 1 isoforms from rat pituitary cells and their association with ATP-gated P2X channels. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2011;174:202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller CM, Boulter NR, Fuller SJ, Zakrzewski AM, Lees MP, Saunders BM, Wiley JS, Smith NC. The role of the P2X(7) receptor in infectious diseases. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002212. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sambasivan V, Murthy KJ, Reddy R, Vijayalakshimi V, Hasan Q. P2X7 gene polymorphisms and risk assessment for pulmonary tuberculosis in Asian Indians. Dis Markers. 2010;28:43–48. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coutinho-Silva R, Stahl L, Raymond MN, Jungas T, Verbeke P, Burnstock G, Darville T, Ojcius DM. Inhibition of chlamydial infectious activity due to P2X7R-dependent phospholipase D activation. Immunity. 2003;19:403–412. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00235-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coutinho-Silva R, Perfettini JL, Persechini PM, Dautry-Varsat A, Ojcius DM. Modulation of P2Z/P2X(7) receptor activity in macrophages infected with Chlamydia psittaci. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C81–C89. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Coutinho-Silva R, Ojcius DM. Role of extracellular nucleotides in the immune response against intracellular bacteria and protozoan parasites. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:1271–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Cytochrome c dysregulation induced by HIV infection of astrocytes results in bystander apoptosis of uninfected astrocytes by an IP and calcium-dependent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jnc.12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eugenin EA, Clements JE, Zink MC, Berman JW. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human astrocytes disrupts blood-brain barrier integrity by a gap junction-dependent mechanism. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:9456–9465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1460-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Gap junctions mediate human immunodeficiency virus-bystander killing in astrocytes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:12844–12850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4154-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tran Van Nhieu G, Clair C, Bruzzone R, Mesnil M, Sansonetti P, Combettes L. Connexin-dependent inter-cellular communication increases invasion and dissemination of Shigella in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:720–726. doi: 10.1038/ncb1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Romero S, Grompone G, Carayol N, Mounier J, Guadagnini S, Prevost MC, Sansonetti PJ, Van Nhieu GT. ATP-mediated Erk1/2 activation stimulates bacterial capture by filopodia, which precedes Shigella invasion of epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:508–519. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kasper CA, Sorg I, Schmutz C, Tschon T, Wischnewski H, Kim ML, Arrieumerlou C. Cell-cell propagation of NF-kappaB transcription factor and MAP kinase activation amplifies innate immunity against bacterial infection. Immunity. 2010;33:804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Velasquez Almonacid LA, et al. Role of connexin-43 hemichannels in the pathogenesis of Yersinia enterocolitica. Vet J. 2009;182:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Esen N, Shuffield D, Syed MM, Kielian T. Modulation of connexin expression and gap junction communication in astrocytes by the gram-positive bacterium S. aureus. Glia. 2007;55:104–117. doi: 10.1002/glia.20438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karpuk N, Burkovetskaya M, Fritz T, Angle A, Kielian T. Neuroinflammation leads to region-dependent alterations in astrocyte gap junction communication and hemichannel activity. J Neurosci. 2011;31:414–425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5247-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Robertson J, Lang S, Lambert PA, Martin PE. Peptidoglycan derived from Staphylococcus epidermidis induces Connexin43 hemichannel activity with consequences on the innate immune response in endothelial cells. Biochem J. 2010;432:133–143. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ross SA, Novak Z, Kumbla RA, Zhang K, Fowler KB, Boppana S. GJB2 and GJB6 mutations in children with congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:687–691. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180536609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Housley GD, Bringmann A, Reichenbach A. Purinergic signaling in special senses. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang N, et al. Paracrine signaling through plasma membrane hemichannels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khan Z, Yaiw KC, Wilhelmi V, Lam H, Rahbar A, Stragliotto G, Soderberg-Naucler C. Human cytomegalovirus immediate early proteins promote degradation of connexin 43 and disrupt gap junction communication: implications for a role in gliomagenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2013 doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu X, Sun L, Torii M, Rakic P. Connexin 43 controls the multipolar phase of neuronal migration to the cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8280–8285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205880109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Elias LA, Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. Gap junction adhesion is necessary for radial migration in the neocortex. Nature. 2007;448:901–907. doi: 10.1038/nature06063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu X, Hashimoto-Torii K, Torii M, Ding C, Rakic P. Gap junctions/hemichannels modulate interkinetic nuclear migration in the forebrain precursors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4197–4209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4187-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hsiao HJ, Liu PA, Yeh HI, Wang CY. Classical swine fever virus down-regulates endothelial connexin 43 gap junctions. Arch Virol. 2010;155:1107–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0693-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koster-Patzlaff C, Hosseini SM, Reuss B. Persistent Borna Disease Virus infection changes expression and function of astroglial gap junctions in vivo and in vitro. Brain Res. 2007;1184:316–332. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Koster-Patzlaff C, Hosseini SM, Reuss B. Layer specific changes of astroglial gap junctions in the rat cerebellar cortex by persistent Borna Disease Virus infection. Brain Res. 2008;1219:143–158. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koster-Patzlaff C, Hosseini SM, Reuss B. Loss of connexin36 in rat hippocampus and cerebellar cortex in persistent Borna disease virus infection. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009;37:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fatemi SH, Folsom TD, Reutiman TJ, Sidwell RW. Viral regulation of aquaporin 4, connexin 43, microcephalin and nucleolin. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Musee J, Mbuy GN, Woodruff RI. Antiviral agents alter ability of HSV-2 to disrupt gap junctional intercellular communication between mammalian cells in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2002;56:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fischer NO, Mbuy GN, Woodruff RI. HSV-2 disrupts gap junctional intercellular communication between mammalian cells in vitro. J Virol Methods. 2001;91:157–166. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(00)00260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Knabb MT, Danielsen CA, McShane-Kay K, Mbuy GK, Woodruff RI. Herpes simplex virus-type 2 infectivity and agents that block gap junctional intercellular communication. Virus Res. 2007;124:212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Crow DS, Beyer EC, Paul DL, Kobe SS, Lau AF. Phosphorylation of connexin43 gap junction protein in uninfected and Rous sarcoma virus-transformed mammalian fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1754–1763. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Crow DS, Kurata WE, Lau AF. Phosphorylation of connexin43 in cells containing mutant src oncogenes. Oncogene. 1992;7:999–1003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Filson AJ, Azarnia R, Beyer EC, Loewenstein WR, Brugge JS. Tyrosine phosphorylation of a gap junction protein correlates with inhibition of cell-to-cell communication. Cell Growth Differ. 1990;1:661–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ashrafi GH, Pitts JD, Faccini A, McLean P, O'Brien V, Finbow ME, Campo S. Binding of bovine papillomavirus type 4 E8 to ductin (16K proteolipid), down-regulation of gap junction intercellular communication and full cell transformation are independent events. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:689–694. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-3-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Faccini AM, Cairney M, Ashrafi GH, Finbow ME, Campo MS, Pitts JD. The bovine papillomavirus type 4 E8 protein binds to ductin and causes loss of gap junctional intercellular communication in primary fibroblasts. J Virol. 1996;70:9041–9045. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.9041-9045.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cosenza MA, Zhao ML, Si Q, Lee SC. Human brain parenchymal microglia express CD14 and CD45 and are productively infected by HIV-1 in HIV-1 encephalitis. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:442–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wiley CA, Schrier RD, Nelson JA, Lampert PW, Oldstone MB. Cellular localization of human immunodeficiency virus infection within the brains of acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7089–7093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Conant K, Tornatore C, Atwood W, Meyers K, Traub R, Major EO. In vivo and in vitro infection of the astrocyte by HIV-1. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1994;4:287–289. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(06)80269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Gap junctions mediate human immunodeficiency virus-bystander killing in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12844–12850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4154-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ohagen A, et al. Apoptosis induced by infection of primary brain cultures with diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: evidence for a role of the envelope. J Virol. 1999;73:897–906. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.897-906.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tornatore C, Chandra R, Berger JR, Major EO. HIV-1 infection of subcortical astrocytes in the pediatric central nervous system. Neurology. 1994;44:481–487. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.3_part_1.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bagasra O, Lavi E, Bobroski L, Khalili K, Pestaner JP, Tawadros R, Pomerantz RJ. Cellular reservoirs of HIV-1 in the central nervous system of infected individuals: identification by the combination of in situ polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry. AIDS. 1996;10:573–585. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199606000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nuovo GJ, Gallery F, MacConnell P, Braun A. In situ detection of polymerase chain reaction-amplified HIV-1 nucleic acids and tumor necrosis factor-alpha RNA in the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 1994;144:659–666. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Takahashi K, Wesselingh SL, Griffin DE, McArthur JC, Johnson RT, Glass JD. Localization of HIV-1 in human brain using polymerase chain reaction/in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:705–711. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Churchill MJ, Wesselingh SL, Cowley D, Pardo CA, McArthur JC, Brew BJ, Gorry PR. Extensive astrocyte infection is prominent in human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:253–258. doi: 10.1002/ana.21697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Eugenin EA, Clements JE, Zink MC, Berman JW. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of human astrocytes disrupts blood-brain barrier integrity by a gap junction-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci. 2011;31:9456–9465. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1460-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eugenin EA, Berman JW. Cytochrome C dysregulation induced by HIV infection of astrocytes results in bystander apoptosis of uninfected astrocytes by an IP and Calcium dependent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jnc.12443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Eugenin EA, King JE, Hazleton JE, Major EO, Bennett MV, Zukin RS, Berman JW. Differences in NMDA receptor expression during human development determine the response of neurons to HIV-tat-mediated neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicity research. 2011;19:138–148. doi: 10.1007/s12640-010-9150-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Orellana JA, Saez JC, Bennett MV, Berman JW, Morgello S, Eugenin EA. HIV increases the release of dickkopf-1 protein from human astrocytes by a Cx43 hemichannel-dependent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jnc.12492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Li W, Henderson LJ, Major EO, Al-Harthi L. IFN-gamma mediates enhancement of HIV replication in astrocytes by inducing an antagonist of the beta-catenin pathway (DKK1) in a STAT 3-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2011;186:6771–6778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Seror C, et al. Extracellular ATP acts on P2Y2 purinergic receptors to facilitate HIV-1 infection. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:1823–1834. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Orellana JA, Velasquez S, Williams DW, Saez JC, Berman JW, Eugenin EA. Pannexin1 hemichannels are critical for HIV infection of human primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2013 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0512249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hazleton JE, Berman JW, Eugenin EA. Purinergic receptors are required for HIV-1 infection of primary human macrophages. J Immunol. 2012;188:4488–4495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pingle SC, et al. Activation of the adenosine A1 receptor inhibits HIV-1 tat-induced apoptosis by reducing nuclear factor-kappaB activation and inducible nitric-oxide synthase. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:856–867. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.031427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fotheringham J, Mayne M, Holden C, Nath A, Geiger JD. Adenosine receptors control HIV-1 Tat-induced inflammatory responses through protein phosphatase. Virology. 2004;327:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.By Y, Durand-Gorde JM, Condo J, Lejeune PJ, Fenouillet E, Guieu R, Ruf J. Monoclonal antibody-assisted stimulation of adenosine A2A receptors induces simultaneous downregulation of CXCR4 and CCR5 on CD4+ T-cells. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:1073–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]