Abstract

Objective

To examine guideline-based use of prophylactic antibiotics in patients who underwent gynecologic surgery.

Methods

We identified women who underwent gynecologic surgery between 2003–2010. Procedures were stratified as antibiotic-appropriate (abdominal, vaginal, or laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy) or antibiotic-inappropriate (oophorectomy, cystectomy, tubal ligation, dilation and curettage, myomectomy, and tubal ligation). Antibiotic use was examined using hierarchical regression models.

Results

Among 545,332 women who underwent procedures for which antibiotics were recommended, 87.1% received appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis, 2.3% received non-guideline recommended antibiotics, and 10.6% received no prophylaxis. Use of antibiotics increased from 88.0% in 2003 to 90.7% in 2010 (P<0.001). After excluding patients with infectious complications, 26.7% of women received antibiotics more than 24 hours after surgery. Among 491,071, who had operations in which antibiotics were not recommended, antibiotics were administered to 197,226 (40.2%) women. Use of nonguideline based antibiotics also increased over time from 33.4% in 2003 to 43.7% in 2010 (P<0.001). Year of diagnosis, surgeon and hospital procedural volume, and area of residence were the strongest predictors of guideline-based and non-guideline-based antibiotic use.

Conclusion

Although use of antibiotics is high for women who should receive antibiotics, antibiotics are increasingly being administered to women for whom the drugs are of unproven benefit.

Introduction

Surgical site infections (SSI) are a major cause of morbidity in patients undergoing operative procedures.1–4 Surgical site infections not only result in substantial pain and suffering, but are also costly to treat; one study estimated that the development of an SSI resulted, on average, in over $10,000 of excess hospital costs and prolonged the length of stay by over 4 days.1 For women undergoing hysterectomy, wound complications have been reported to occur in over 20% of patients in some reports.5

Over the past four decades numerous studies have suggested that the administration of perioperative antibiotics reduces infectious morbidity for high-risk surgical procedures.6–10 For hysterectomy, a clean contaminated procedure in which the vagina is entered, one meta-analysis of 17 studies that included 2752 subjects noted that antibiotic prophylaxis reduced the infection rate by 65%.8 Based on these data, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends antibiotic prophylaxis for hysterectomy, urogynecologic procedures, hysterosalpingogram, and induced abortion.9 For procedures with a low risk of infection, these guidelines do not recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for lower risk, clean procedures including operative and diagnostic laparoscopy, tubal sterilization, hysteroscopy, and laparotomy.9 Numerous other professional societies have developed similar guidelines for prophylaxis for high-risk surgeries.10–13

In addition to published guidelines, national efforts have been developed to promote proper antibiotic use.4 Despite these efforts, little is known about the actual adherence to recommendations for the allocation of perioperative antibiotics in women undergoing gynecologic surgery. We performed a population-based analysis to determine the patterns and predictors of guideline-based use and prolonged use of antibiotics in women who underwent gynecologic surgery.

Methods

Data Source

The Perspective database (Premier Inc, Charlotte, NC), a voluntary database that captures data from more than 500 acute-care hospitals from throughout the United States was used.14 Participating hospitals submit electronic updates on a quarterly basis. The data is audited regularly to ensure quality and integrity. The database captures clinical and demographic data, diagnoses, procedures, and all billed services rendered during a hospital stay,15 and therefore contains information on all drugs, devices, radiologic tests, laboratory tests and therapeutic services rendered during a patient's hospitalization. In 2006, nearly 5.5 million hospital discharges that represent approximately 15% of all hospitalizations were captured in the database.16 The database has been validated and utilized in a large number of outcomes studies. The Columbia University Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt.

Patient Selection

We analyzed women aged 18 years or older who underwent inpatient or outpatient gynecologic surgery between 2003 and the first quarter of 2010. Surgical procedures were identified through ICD-9 coding. Based on published practice guidelines by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, procedures were classified as either antibiotic-appropriate procedures, those operations in which antibiotics were recommended, or antibiotic-inappropriate procedures, surgeries in which antibiotics were not routinely recommended.9 Antibiotic appropriate procedures included: abdominal hysterectomy (ICD-9 68.3, 68.39, 68.4, 68.49, 68.90), vaginal hysterectomy (ICD-9 68.5, 68.59), and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (ICD-9 68.31, 68.41, 68.51). Antibiotic-inappropriate procedures included: myomectomy (ICD-9 68.29), open and laparoscopic oophorectomy with or with salpingectomy (ICD-9 65.3x, 65.4x, 65.6x, 65.6x), open and laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy ICD-9 65.2x), dilation and curettage with or without hysteroscopy (ICD-9 69.0, 69.09, 68.12), and laparoscopic tubal ligation (ICD-9 66.2, 66.21, 66.22, 66.29).9

Patients were classified through a hierarchy, based on the order of procedures listed above, so that they were only included once even if they underwent multiple procedures. For example, if a patient underwent hysteroscopy along with a tubal ligation they were classified in the hysteroscopy group. Pregnant patients, including those with ectopic gestations and patients who underwent abortion, were excluded from the analysis (ICD-9 codes 630.x–679.x). To capture elective or planned surgery, we only included women who underwent surgery on the first day of hospitalization.17

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

Demographic data analyzed included age (<40, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and >70 years of age), year of surgery, race (white, black, Hispanic, and other), marital status, and insurance status (Medicare, Medicaid, commercial, self-pay, and unknown). Hospitals in which patients were treated were characterized based on location (metropolitan, non-metropolitan), region of the country (northeast, midwest, west, south), size (<400 beds, 400–600 beds, and >600 beds) and teaching status (teaching, non-teaching). Risk adjustment for medical comorbidities was performed using the Elixhauser comorbidity index. Patients were categorized based on the number of medical comorbidities as 0, 1, 2, and ≥3 as previously reported.18

A composite surgical volume for all procedures was determined for hospitals and surgeons. Annualized procedural volume was estimated for each surgeon or hospital by dividing the total number of procedures performed by the number of years in which the individual hospital or surgeon contributed at least one operation.19,20 The volume distributions were examined visually and volume classified into approximately equal patient-based quartiles for surgeons (lowest ≤18.5 cases per year, second 18.51–33.99 cases per year, third 34.00–56.60 cases per year, and highest 56.6 cases per year) and hospitals (lowest <320.15 cases per year, second 320.15–524.15 cases per year, third 524.16–888.25 cases per year, and highest >888.25 cases per year).

Antibiotic Utilization

The database captures all drugs administered to patients and records the hospital day on which the drug is administered. To capture perioperative antibiotic use, we classified antibiotics administered on hospital day 1 as perioperative antibiotics. Antibiotics were categorized based on whether the antibiotic has been recommended in published guidelines for gynecologic surgery.9 For this classification schema, we used a permissive definition of guideline-adherent antibiotics and included any drug or class of drugs previously described in the ACOG guidelines, including: cefazolin, cefotetan, cefoxitin, cefuroxime, ampicillin-sulbactam, clindamycin, gentamicin, aztreonam, metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, enoxacin, gatifloxacin, levofloxacin, lomefloxacin, moxifloxicin, nalidixic acid, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, trovafloxacin, grepafloxacin, sparfloxacin, temafloxacin. Other antibiotics were categorized as non-guideline based antibiotics.9

Statistical Analysis

Frequency distributions between categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests. Separate analyses were performed for antibiotic-appropriate and antibiotic-inappropriate procedures. Hierarchical logistic regression analysis was used to determine factors associated with use of perioperative antibiotics. These models included all patient, physician, and hospital characteristics as well as physician-specific and hospital-specific random effects to account for clustering. For antibiotic-appropriate procedures, we modeled failure to utilize antibiotics, while for antibiotic-inappropriate procedures we modeled use of perioperative antibiotics. All outcomes are reported as risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

A total of 1,036,403 women, including 545,332 (52.6%) who underwent procedures in which antibiotics were recommended and 491,071 (47.4%) who had operations in which antibiotics were not recommended, were identified. Within the cohort of women who had procedures in which antibiotics were recommended, 475,180 (87.1%) received appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis, while 12,451 (2.3%) received non-guideline recommended antibiotics and 57,901 (10.6%) received no prophylaxis. Within this cohort, use of antibiotics increased from 88.0% in 2003 to 90.7% in 2010 (P<0.001). Likewise, for each procedure antibiotic use increased over time: abdominal hysterectomy (87.4% in 2003 to 89.0% in 2010) laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (89.2% to 91.5%) and vaginal hysterectomy (88.9% to 92.4%) (P<0.001 for all) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

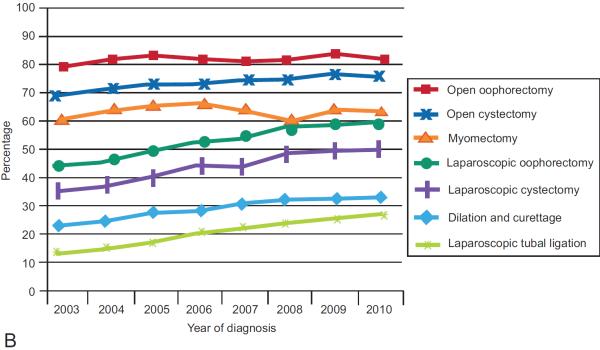

Use of antibiotics for patients undergoing (A) antibiotic-appropriate procedures and (B) antibiotic-inappropriate procedures.

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the patients in which antibiotics were recommended. In an adjusted, multivariable model, patients who underwent surgery more recently, those residing in non-metropolitan areas, those with 3 or more medical comorbidities, women living in areas other than the eastern U.S., and patients treated by higher volume surgeons were more likely to receive antibiotics. High-volume surgeons were 41% less likely to omit antibiotics (RR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.52–0.66) than low-volume surgeons, while non-teaching hospitals were 25% less likely than teaching hospitals to omit antibiotics (RR=0.75; 95% CI, 0.70–0.81).

Table 1.

Patterns of Antibiotic Use Among Patients Who Underwent Gynecologic Procedures for Which Antibiotics are Recommended

| No Antibiotics | Inappropriate Antibiotic | Multivariable RR of Not Receiving Antibiotic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | P * | ||

| 57,901 | (10.6) | 12,451 | (2.3) | |||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||||

| <40 | 14,161 | (9.5) | 3723 | (2.5) | Referent | |

| 40–49 | 27,909 | (11.0) | 5639 | (2.2) | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | |

| 50–59 | 9898 | (11.2) | 1859 | (2.1) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | |

| 60–69 | 3564 | (11.3) | 718 | (2.3) | 0.96 (0.92–1.00)* | |

| ≥70 | 2369 | (11.5) | 512 | (2.5) | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | |

| Year of diagnosis | <0.001 | |||||

| 2003 | 8323 | (12.0) | 317 | (4.5) | Referent | |

| 2004 | 8270 | (11.7) | 2432 | (3.5) | 0.94 (0.91–0.97)* | |

| 2005 | 6935 | (9.8) | 1965 | (2.8) | 0.78 (0.76–0.81)* | |

| 2006 | 8095 | (10.0) | 1996 | (2.5) | 0.73 (0.70–0.75)* | |

| 2007 | 8467 | (10.9) | 1306 | (1.7) | 0.80 (0.77–0.83)* | |

| 2008 | 7916 | (10.3) | 862 | (1.1) | 0.77 (0.74–0.80)* | |

| 2009 | 8165 | (10.1) | 650 | (0.8) | 0.74 (0.71–0.77)* | |

| 2010 | 1730 | (9.3) | 113 | (0.6) | 0.67 (0.64–0.71)* | |

| Race | <0.001 | |||||

| White | 34,274 | (9.6) | 8183 | (2.3) | Referent | |

| Black | 10,098 | (12.2) | 1862 | (2.3) | 1.07 (1.04–1.10)* | |

| Hispanic | 3251 | (12.3) | 501 | (1.9) | 1.16 (1.10–1.21)* | |

| Other/unknown | 10,278 | (13.0) | 1905 | (2.4) | 1.10 (1.06–1.14)* | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||||

| Married | 31,489 | (9.7) | 7617 | (2.3) | Referent | |

| Single | 9582 | (11.5) | 1765 | (2.1) | 1.02 (0.99–1.04) | |

| Unknown | 16,830 | (12.3) | 3069 | (2.3) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06)* | |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | |||||

| Commercial | 45,066 | (10.7) | 9543 | (2.3) | Referent | |

| Medicare | 5063 | (11.0) | 1138 | (2.5) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | |

| Medicaid | 4410 | (10.1) | 1060 | (2.4) | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) | |

| Uninsured | 1659 | (10.2) | 289 | (1.8) | 1.03 (0.97–1.08) | |

| Unknown | 1703 | (9.0) | 421 | (2.2) | 1.04 (0.99–1.10) | |

| Area of residence | <0.001 | |||||

| Metropolitan | 53,433 | (11.3) | 10,033 | (2.1) | Referent | |

| Non-metropolitan | 4468 | (6.0) | 2418 | (3.3) | 0.74 (0.66–0.83)* | |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | <0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 25,861 | (10.4) | 6112 | (2.5) | Referent | |

| 1 | 16,938 | (10.8) | 3347 | (2.1) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | |

| 2 | 8158 | (11.0) | 1467 | (2.0) | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | |

| ≥3 | 6944 | (10.8) | 1525 | (2.4) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99)* | |

| Region | <0.001 | |||||

| Eastern | 14,291 | (25.7) | 642 | (2.1) | Referent | |

| Midwest | 12,626 | (11.2) | 642 | (1.2) | 0.41 (0.38–0.46)* | |

| South | 24,463 | (8.4) | 8042 | (2.8) | 0.36 (0.33–0.39)* | |

| West | 6521 | (7.7) | 1398 | (1.7) | 0.33 (0.30–0.37)* | |

| Hospital teaching status | <0.001 | |||||

| Teaching | 27,785 | (13.9) | 4468 | (2.2) | Referent | |

| Non-teaching | 30,116 | (8.7) | 7983 | (2.3) | 0.75 (0.70–0.81)* | |

| Beds | <0.001 | |||||

| <400 | 30,286 | (10.3) | 7283 | (2.5) | Referent | |

| 400–600 | 13,287 | (9.1) | 3285 | (2.2) | 0.75 (0.70–0.81)* | |

| >600 | 14,328 | (13.6) | 1883 | (1.8) | 1.11 (1.01–1.21)* | |

| Hospital volume | <0.001 | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 14,277 | (9.7) | 3857 | (2.6) | Referent | |

| Second quartile | 17,174 | (12.4) | 3356 | (2.4) | 1.18 (1.09–1.28)* | |

| Third quartile | 15,276 | (10.9) | 3327 | (2.4) | 1.01 (0.92–1.09) | |

| Highest quartile | 11,174 | (9.4) | 1911 | (1.6) | 0.94 (0.85–1.03) | |

| Physician volume | <0.001 | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 18,177 | (13.7) | 2501 | (1.9) | Referent | |

| Second quartile | 15,345 | (11.1) | 2820 | (2.0) | 0.88 (0.82–0.95)* | |

| Third quartile | 11,944 | (8.8) | 3531 | (2.6) | 0.72 (0.65–0.79)* | |

| Highest quartile | 10,836 | (8.4) | 3396 | (2.6) | 0.59 (0.52–0.66)* | |

| Unknown | 1599 | (17.2) | 203 | (2.2) | 0.92 (0.67–1.25) | |

| Procedure | <0.001 | |||||

| Abdominal hysterectomy | 32,685 | (11.6) | 6716 | (2.4) | Referent | |

| Vaginal hysterectomy | 11,651 | (9.5) | 3039 | (2.5) | 0.90 (0.88–0.93)* | |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy | 13,565 | (9.8) | 2696 | (1.9) | 0.99 (0.97–1.02) | |

P-value derived from chi square tests comparing appropriate antibiotics, inappropriate antibiotics, and no antibiotics for each class variable.

Among women who underwent a procedure in which antibiotics were not recommended, antibiotics were administered to 197,226 (40.2%) women. Use of antibiotics increased over time from 33.4% in 2003 to 43.7% in 2010 (P<0.001). Increased antibiotic use over time from 2003 to 2010 was noted for all of the individual procedures: myomectomy (63.1% to 66.5%), oophorectomy (79.0% to 82.6%), laparoscopic oophorectomy (47.2% to 63.3%), cystectomy (69.1% to 77.1%), laparoscopic cystectomy (37.2% to 50.9%), dilation and curettage with or without hysteroscopy (23.1% to 33.2%) and laparoscopic tubal ligation (14.9% to 29.6%) (P<0.001 for all) (Figure 1B).

Use of antibiotics in patients who underwent procedures in which antibiotics were not required is shown in Table 2. In a multivariable model, patients treated more recently were more likely to receive antibiotics (RR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.29–1.36 for 2010 compared to 2003). Medicaid (RR=0.93; 95% CI, 0.92–0.95) and uninsured (RR=0.97; 95% CI, 0.94–0.99) women as well as those treated at non-metropolitan centers (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.90–0.98) were less likely to receive antibiotics, while patients in areas other than the eastern U.S. were more likely to receive antibiotics. High-volume hospitals and high-volume surgeons were less likely to administer perioperative antibiotics in these women; compared to low-volume surgeons, high-volume surgeons were 13% less likely to prescribe antibiotics (RR=0.87; 95% CI, 0.83–0.92). Women who underwent laparotomy were more likely to receive antibiotics than those who had laparoscopic surgery.

Table 2.

Patterns of Antibiotic Use Among Patients Who Underwent Gynecologic Procedures for Which Antibiotics are Not Recommended

| No Antibiotics | Antibiotic | Multivariable RR of Receipt of Any Antibiotic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | P | ||

| 293,845 | (59.8) | 197,226 | (40.2) | |||

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||||

| <40 | 151,111 | (60.9) | 96,973 | (39.1) | Referent | |

| 40–49 | 81,708 | (60.2) | 54,100 | (39.8) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | |

| 50–59 | 37,978 | (61.6) | 23,712 | (38.4) | 0.91 (0.90–0.93) | |

| 60–69 | 13,724 | (52.8) | 12,288 | (47.2) | 0.94 (0.92–0.96) | |

| ≥70 | 9324 | (47.9) | 10,153 | (52.1) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | |

| Year of diagnosis | <0.001 | |||||

| 2003 | 43,319 | (66.6) | 21,763 | (33.4) | Referent | |

| 2004 | 37,309 | (63.3) | 21,671 | (36.7) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | |

| 2005 | 35,648 | (60.5) | 23,325 | (39.6) | 1.12 (1.10–1.15) | |

| 2006 | 39,282 | (59.3) | 27,1019 | (40.8) | 1.17 (1.15–1.20) | |

| 2007 | 37,262 | (58.1) | 26,899 | (41.9) | 1.20 (1.17–1.22) | |

| 2008 | 42,907 | (57.1) | 32,183 | (42.9) | 1.25 (1.23–1.28) | |

| 2009 | 47,038 | (56.8) | 35,768 | (43.2) | 1.30 (1.28–1.33) | |

| 2010 | 11,080 | (56.3) | 8598 | (43.7) | 1.32 (1.29–1.36) | |

| Race | <0.001 | |||||

| White | 194,682 | (61.0) | 124,544 | (39.0) | Referent | |

| Black | 39,033 | (55.6) | 31,130 | (44.4) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | |

| Hispanic | 15,294 | (53.6) | 13,251 | (46.4) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | |

| Other/unknown | 44,836 | (61.3) | 28,301 | (38.7) | 0.98 (0.97–1.00) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||||

| Married | 156,892 | (59.7) | 105,809 | (40.3) | Referent | |

| Single | 64,395 | (59.3) | 44,188 | (40.7) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | |

| Unknown | 72,558 | (60.6) | 47,229 | (39.4) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | |

| Insurance status | <0.001 | |||||

| Commercial | 202,873 | (58.7) | 142,704 | (41.3) | Referent | |

| Medicare | 21,445 | (52.0) | 19,796 | (48.0) | 1.00 (0.97–1.02) | |

| Medicaid | 52,032 | (70.4) | 21,868 | (29.6) | 0.93 (0.92–0.95) | |

| Uninsured | 7978 | (55.6) | 6372 | (44.4) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | |

| Unknown | 9517 | (59.5) | 6486 | (40.5) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | |

| Area of residence | <0.001 | |||||

| Metropolitan | 255,438 | (59.2) | 176,112 | (40.8) | Referent | |

| Non-metropolitan | 38,407 | (64.5) | 21,114 | (35.5) | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | |

| Elixhauser comorbidity | <0.001 | |||||

| index | ||||||

| 0 | 180,884 | (63.2) | 105,539 | (36.9) | Referent | |

| 1 | 62,532 | (57.8) | 45,726 | (42.2) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | |

| 2 | 26,250 | (55.2) | 21,281 | (44.8) | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) | |

| ≥3 | 24,179 | (49.5) | 24,680 | (50.5) | 1.12 (1.10–1.13) | |

| Region | <0.001 | |||||

| Eastern | 44,229 | (72.3) | 16,909 | (27.7) | Referent | |

| Midwest | 75,250 | (68.0) | 35,485 | (32.0) | 1.12 (1.07–1.18) | |

| South | 141,687 | (55.4) | 114,159 | (44.6) | 1.59 (1.53–1.66) | |

| West | 32,679 | (51.6) | 30,673 | (48.4) | 1.66 (1.58–1.74) | |

| Hospital teaching status | 0.81 | |||||

| Teaching | 111,966 | (59.8) | 75,216 | (40.2) | Referent | |

| Non-teaching | 181,879 | (59.9) | 122,010 | (40.2) | 1.08 (1.05–1.11) | |

| Beds | <0.001 | |||||

| <400 | 159,144 | (60.8) | 102,495 | (39.2) | Referent | |

| 400–600 | 72,668 | (57.9) | 52,800 | (42.1) | 1.07 (1.04–1.10) | |

| >600 | 62,033 | (59.7) | 41,931 | (40.3) | 1.08 (1.03–1.12) | |

| Hospital volume | <0.001 | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 67,727 | (60.4) | 44,390 | (39.6) | Referent | |

| Second quartile | 72,310 | (60.2) | 47,819 | (39.8) | 0.96 (0.92–0.99) | |

| Third quartile | 69,886 | (58.3) | 50,023 | (41.7) | 0.95 (0.91–0.98) | |

| Highest quartile | 83,922 | (60.4) | 54,994 | (39.6) | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | |

| Physician volume | <0.001 | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 67,483 | (55.1) | 54,910 | (44.9) | Referent | |

| Second quartile | 67,660 | (59.3) | 46,352 | (40.7) | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | |

| Third quartile | 74,907 | (62.9) | 44,264 | (37.1) | 0.85 (0.81–0.88) | |

| Highest quartile | 77,690 | (61.6) | 48,340 | (38.4) | 0.87 (0.83–0.92) | |

| Unknown | 6105 | (64.5) | 3360 | (35.5) | 1.00 (0.88–1.14) | |

| Procedure | <0.001 | |||||

| Laparoscopic oophorectomy | 20,938 | (43.4) | 27,365 | (56.7) | Referent | |

| Open oophorectomy | 8707 | (18.6) | 38,015 | (81.4) | 1.46 (1.44–1.49) | |

| Laparoscopic cystectomy | 15,710 | (55.1) | 12,803 | (44.9) | 0.80 (0.78–0.81) | |

| Open cystectomy | 2881 | (26.7) | 7926 | (73.3) | 1.31 (1.28–1.35) | |

| Laparoscopic tubal ligation | 77,580 | (77.7) | 22,271 | (22.3) | 0.47 (0.46–0.48) | |

| Dilation and curettage | 155,239 | (70.7) | 64,208 | (29.3) | 0.57 (0.56–0.58) | |

| Myomectomy | 12,790 | (34.2) | 24,638 | (65.8) | 1.11 (1.09–1.13) | |

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the use of perioperative antibiotics in women undergoing gynecologic surgery is poorly aligned with published guidelines. Although use of antibiotics is high (87%) for women who should receive antibiotics, antibiotics are being increasingly administered to women for whom the drugs are likely of little benefit.

To promote the utilization of appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis, a national collaborative developed the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) in 2003.4,21,23–26 The SCIP initiatives include perioperative quality measures including several focused on the proper allocation of antibiotics. Importantly, hysterectomy is one of the procedures targeted in the SCIP collaborative. While hospital participation in SCIP is voluntary, reimbursement by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is reduced by 2% if hospitals do not report their outcomes.26 Our data suggest that use of antibiotic prophylaxis for hysterectomy is high.

While use of antibiotics for appropriate procedures was relatively high, we also noted that antibiotics were frequently (40%) administered for procedures where the drugs are of little benefit. Other studies have also noted that the introduction of quality measures often leads to unintended overuse of medications.27–29 After CMS adopted a quality measure that required antibiotic administration within 4 hours of hospital arrival for patients with community acquired pneumonia, there was a dramatic increase in the use of antibiotics for patients who did not have pneumonia.28,29 Similarly, guidelines for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for non-surgical patients may promote pharmacologic prophylaxis in very low-risk patients and in those with contraindications to anticoagulation.27 Inappropriate use of antibiotics in low-risk patients not only exposes patients to toxicity with little potential benefit, but also leads to substantial resource utilization and may alter patterns of antimicrobial resistance. Concern about non-compliance with a quality metric may in part explain the overuse of perioperative antibiotics for gynecologic procedures that we noted.

We found that surgical volume was an important predictor of guideline adherence. Compared to low-volume surgeons, high-volume physicians were 41% less likely to omit antibiotics in patients for whom the drugs were indicated, and 13% less likely to give antibiotics when they were not indicated. While the relationship between surgical volume and morbidity and mortality for gynecologic procedures is modest, there is a more robust association between higher surgical volume and decreased resource utilization for pelvic surgery.30–33 These data suggest that adherence to best practice perioperative guidelines may, at least in part, explain the lower costs incurred by higher volume gynecologic surgeons. Our group has previously demonstrated that higher volume surgeons are also more likely to employ appropriate perioperative prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism.34,35

Non-clinical factors appeared to play an important role in the allocation of perioperative antibiotics. Patients treated in the eastern U.S. were more likely to receive antibiotics regardless of procedure type. Prior studies have shown substantial regional variation in surgical practice patterns.17,31 Patients with a greater number of comorbid medical conditions more frequently received unindicated and prolonged antibiotics while older patients were less likely to receive antibiotics for antibiotic-inappropriate procedures, older women more frequently received prolonged antibiotics. Finally, hospital characteristics were associated with antibiotic use; patients treated at non-teaching hospitals were 25% less likely to receive antibiotics when indicated.

Although our analysis benefits from the inclusion of a large number of women, we acknowledge a number of important limitations. We cannot exclude the possibility that prophylaxis was misclassified in a small number of women. However, the database has been validated and utilized in a number of studies including analyses examining antibiotic utilization.26,36 A priori we chose an inclusive definition of guideline-based antibiotics and included any drug or class of drugs that have been described in published guidelines. Finally, we recognize the fact that just because guidelines do not recommend antibiotics does not necessarily mean that antibiotics are of no benefit in some scenarios. Administrative data is unlikely to capture some clinical scenarios in which antibiotics may be warranted. Clearly antibiotic prophylaxis has been poorly studied for many gynecologic procedures, including after complications, and would benefit from more rigorous prospective trials.

The widespread misuse of perioperative antibiotics for gynecologic surgery suggests that strategies to better align practice patterns with evidence-based recommendations are urgently needed. While most quality initiatives have focused on promoting an intervention, reducing unnecessary treatments could substantially decrease medical waste and lower costs.37 Prior studies have demonstrated moderate success for pay for performance initiatives and public reporting of data.38 Similarly, educational interventions, formalized protocol implementation, and clinical decision support tools linked to electronic order entry have all been proposed to reduce unnecessary testing and treatments.39–41

Acknowledgments

Dr. Wright (NCI R01CA169121-01A1) and Dr. Hershman (NCI R01CA134964) are recipients of grants from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Boltz MM, Hollenbeak CS, Julian KG, Ortenzi G, Dillon PW. Hospital costs associated with surgical site infections in general and vascular surgery patients. Surgery. 2011;150:934–42. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortega G, Rhee DS, Papandria DJ, et al. An evaluation of surgical site infections by wound classification system using the ACS-NSQIP. J Surg Res. 2012;174:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell DA, Jr., Henderson WG, Englesbe MJ, et al. Surgical site infection prevention: the importance of operative duration and blood transfusion--results of the first American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Best Practices Initiative. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:810–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratzler DW, Hunt DR. The surgical infection prevention and surgical care improvement projects: national initiatives to improve outcomes for patients having surgery. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:322–30. doi: 10.1086/505220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clarke-Pearson DL, Geller EJ. Complicatons of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:654–73. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182841594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duff P, Park RC. Antibiotic prophylaxis in vaginal hysterectomy: a review. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55:193S–202S. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198003001-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittendorf R, Aronson MP, Berry RE, et al. Avoiding serious infections associated with abdominal hysterectomy: a meta-analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:1119–24. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90266-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanos V, Rojansky N. Prophylactic antibiotics in abdominal hysterectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACOG practice bulletin No. 104: antibiotic prophylaxis for gynecologic procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1180–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a6d011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leaper D, Burman-Roy S, Palanca A, et al. Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection: summary of NICE guidance. Bmj. 2008;337:a1924. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrill MY, Schimpf MO, Abed H, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for selected gynecologic surgeries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;120:10–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Eyk N, van Schalkwyk J. Antibiotic prophylaxis in gynaecologic procedures. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:382–91. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35222-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Surgical infections. 2013;14:73–156. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright JD, Hershman DL, Shah M, et al. Quality of perioperative venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:978–86. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822c952a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogo-Gupta L, Rodriguez LV, Litwin MS, et al. Trends in surgical mesh use for pelvic organ prolapse from 2000 to 2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:1105–15. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826ebcc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Jama. 2010;303:2359–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiavone MB, Herzog TJ, Ananth CV, et al. Feasibility and economic impact of same-day discharge for women who undergo laparoscopic hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:382, e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ. A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care. 2009;47:626–33. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819432e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wright JD, Lewin SN, Deutsch I, Burke WM, Sun X, Herzog TJ. Effect of surgical volume on morbidity and mortality of abdominal hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1051–9. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright JD, Lewin SN, Deutsch I, Burke WM, Sun X, Herzog TJ. The influence of surgical volume on morbidity and mortality of radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:225, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bratzler DW. The Surgical Infection Prevention and Surgical Care Improvement Projects: promises and pitfalls. Am Surg. 2006;72:1010–6. discussion 21–30, 133–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. [Accessed July 21, 2013];Surgical Care Improvement Project. 2013 at http://www.jointcommission.org/surgical_care_improvement_project/

- 23.Awad SS. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and post-operative surgical site infections. Surgical infections. 2012;13:234–7. doi: 10.1089/sur.2012.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berenguer CM, Ochsner MG, Jr., Lord SA, Senkowski CK. Improving surgical site infections: using National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data to institute Surgical Care Improvement Project protocols in improving surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:737–41. 41–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potenza B, Deligencia M, Estigoy B, et al. Lessons learned from the institution of the Surgical Care Improvement Project at a teaching medical center. Am J Surg. 2009;198:881–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stulberg JJ, Delaney CP, Neuhauser DV, Aron DC, Fu P, Koroukian SM. Adherence to surgical care improvement project measures and the association with postoperative infections. Jama. 2010;303:2479–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baker DW, Qaseem A. Evidence-based performance measures: preventing unintended consequences of quality measurement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:638–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanwar M, Brar N, Khatib R, Fakih MG. Misdiagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia and inappropriate utilization of antibiotics: side effects of the 4-h antibiotic administration rule. Chest. 2007;131:1865–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welker JA, Huston M, McCue JD. Antibiotic timing and errors in diagnosing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:351–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, et al. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. Jama. 2013;309:689–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright JD, Burke WM, Wilde ET, et al. Comparative effectiveness of robotic versus laparoscopic hysterectomy for endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:783–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogo-Gupta LJ, Lewin SN, Kim JH, et al. The effect of surgeon volume on outcomes and resource use for vaginal hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1341–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fca8c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effect of surgical volume on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign indications. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:709–16. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318248f7a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ritch JM, Kim JH, Lewin SN, et al. Venous thromboembolism and use of prophylaxis among women undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1367–74. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821bdd16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright JD, Lewin SN, Shah M, et al. Quality of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in patients undergoing oncologic surgery. Ann Surg. 2011;253:1140–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31821287ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Lahti M, Brody O, Skiest DJ, Lindenauer PK. Antibiotic therapy and treatment failure in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Jama. 2010;303:2035–42. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brook RH. The role of physicians in controlling medical care costs and reducing waste. Jama. 2011;306:650–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eijkenaar F, Emmert M, Scheppach M, Schoffski O. Effects of pay for performance in health care: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Health Policy. 2013;110::115–30. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levick DL, Stern G, Meyerhoefer CD, Levick A, Pucklavage D. “Reducing unnecessary testing in a CPOE system through implementation of a targeted CDS intervention”. BMC medical informatics and decision making. 2013;13:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-13-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vegting IL, van Beneden M, Kramer MH, Thijs A, Kostense PJ, Nanayakkara PW. How to save costs by reducing unnecessary testing: lean thinking in clinical practice. European journal of internal medicine. 2012;23:70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.May TA, Clancy M, Critchfield J, et al. Reducing unnecessary inpatient laboratory testing in a teaching hospital. American journal of clinical pathology. 2006;126:200–6. doi: 10.1309/WP59-YM73-L6CE-GX2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]