Abstract

Approximately 1.7 million children have parents who are incarcerated in prison in the United States, and possibly millions of additional children have a parent incarcerated in jail. Many affected children experience increased risk for developing behavior problems, academic failure, and substance abuse. For a growing number of children, incarcerated parents, caregivers, and professionals, parent– child contact during the imprisonment period is a key issue. In this article, we present a conceptual model to provide a framework within which to interpret findings about parent– child contact when parents are incarcerated. We then summarize recent research examining parent–child contact in context. On the basis of the research reviewed, we present initial recommendations for children’s contact with incarcerated parents and also suggest areas for future intervention and research with this vulnerable population.

Keywords: children, jail, parental incarceration, prison, visitation

In 2007, 1.7 million children had a parent in state or federal prison in the United States, an increase of 80% since 1991 (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008). It is estimated that possibly millions of additional children have a parent in jail (Kemper & Rivara, 1993; Western & Wildeman, 2009). However, the actual number of affected children is unknown because this information is not systematically collected by jails, corrections departments, schools, child welfare systems, or other systems. For a growing number of children, parent–child contact during the incarceration period is a key issue. Family members as well as professionals (e.g., psychologists, attorneys, social workers) question whether children should have contact with incarcerated parents and express concerns about how and when contact occurs, who regulates contact, what types of contact are feasible and desirable, and the effects of contact (or lack thereof) on children.

Given these questions and concerns, our goal in this article is to present current research findings regarding visitation and other forms of contact that occur between children and their incarcerated parents. To place contact issues in a broader context, we briefly summarize the literature examining outcomes of children with incarcerated parents and present a conceptual model to provide a framework within which to interpret findings about parent–child contact. We then summarize national trends regarding children’s contact with incarcerated parents and review recent research findings that have emerged. Finally, we present initial recommendations for children’s contact with incarcerated parents and suggest directions for future research.

Children of Incarcerated Parents in Context

Children’s Outcomes When Parents Are Incarcerated

Children of incarcerated parents are at risk for negative social and academic outcomes, including internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, substance abuse, adult offending and incarceration, truancy, and school failure (see Murray, Farrington, Sekol, & Olsen, 2009, for a quantitative review). Affected children often experience additional risks in their environments (e.g., poverty, parental substance abuse, changes in caregivers); thus, it is unclear whether parental incarceration is the cause of children’s problematic outcomes or a risk marker (Murray & Farrington, 2008). Because large-scale longitudinal studies focusing on children of incarcerated parents have relied on secondary analyses of data that were not collected to assess potential effects of parental incarceration on children, they tell us little about developmental, familial, or contextual processes linking parental incarceration with children’s outcomes. However, numerous smaller scale studies have begun to shed light on such processes, although many of the studies have methodological limitations such as small sample sizes, cross-sectional designs, and lack of comparison groups. Some of these studies have focused on parent–child contact during parental incarceration, and these are reviewed later in this article.

Conceptual Framework

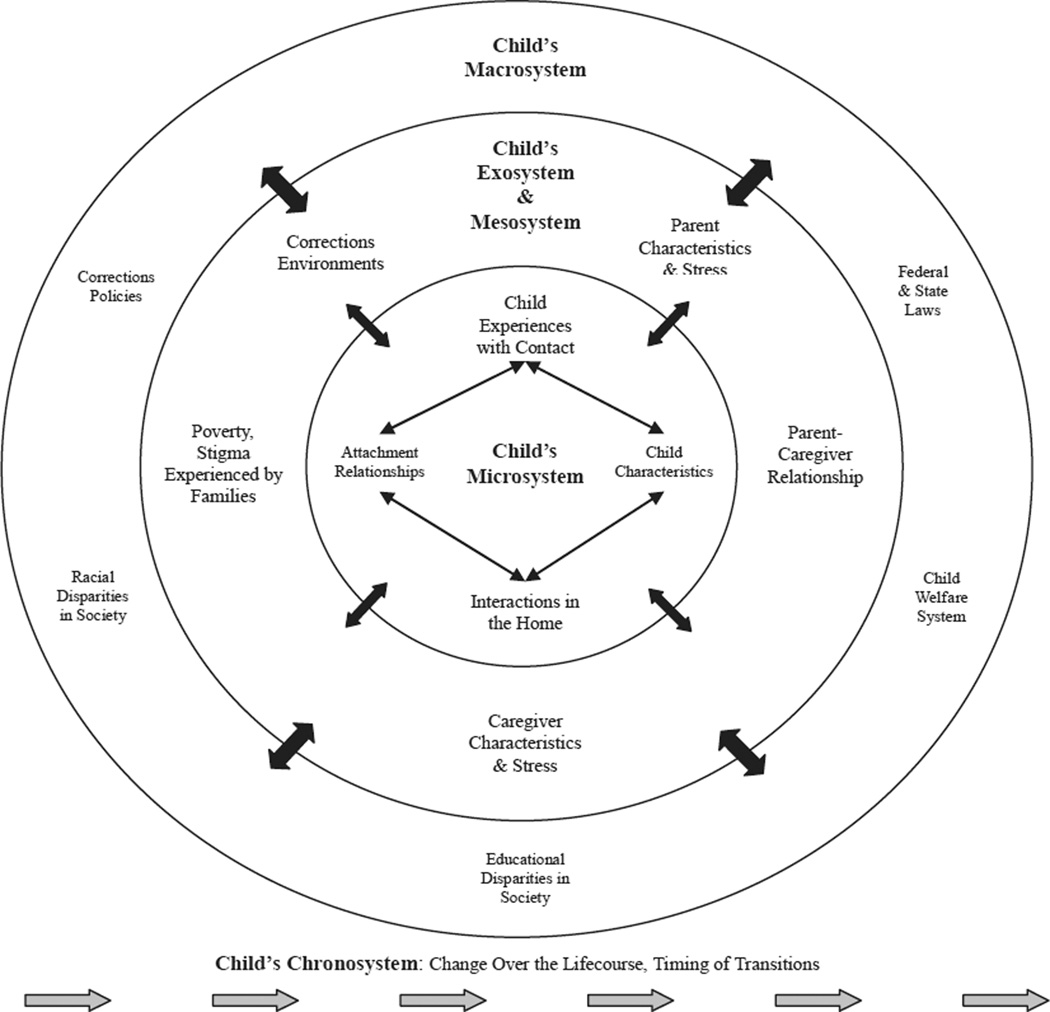

To address the multiple contexts that must be considered when examining children’s contact with incarcerated parents, we use a developmental ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) that is integrated with attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982) (see Figure 1). Ecological models emphasize the importance of multiple contexts, or interrelated settings in which development occurs (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), whereas attachment theory focuses on the quality of the parent–child interactions that contribute to children’s close relationships and well-being across the life span (Bowlby, 1982). Attachment theory also emphasizes the significance of disruptions in relationships that occur when a child is separated from a parent, such as when a parent goes to prison or jail (Poehlmann, 2005b). Both of these models have been applied to parental incarceration previously (Arditti, 2005; Murray & Murray, 2010), although they have not been integrated or applied to parent–child contact experiences when parents are incarcerated.

Figure 1.

Children’s Ecological Contexts Related to Frequency and Quality of Parent–child Contact When Parents Are Incarcerated

Dyadic interactions such as those that contribute to a child’s attachment security are examples of proximal processes, or “enduring forms of interaction in the immediate environment” (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994, p. 572). Proximal processes are seen as key contextual mediators, or “the primary engines” of development (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994, p. 572). Bronfenbrenner (1979) originally referred to the context in which proximal processes occur as the child’s microsystem, or the activities, roles, and relationships experienced by the child.

Microsystem factors

Children’s attachment relationships and contact with parents are considered part of the child’s microsystem. Previous research has found that early attachment quality is an important predictor of children’s later social and emotional functioning (see R. A. Thompson, 2008, for a review). A child who has developed a secure attachment derives comfort from contact with the attachment figure when distressing or threatening situations arise and uses the attachment figure as a base from which to explore the environment with increasing confidence over time (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). In contrast, insecure, and especially disorganized, attachments are considered risk factors for emerging psychopathology (R. A. Thompson, 2008).

For children of incarcerated parents, key microsystem processes that are important for the development of secure attachments and other competencies involve caregiving interactions that occur within the home (Poehlmann, Park, et al., 2008) as well as ongoing contacts with incarcerated parents (Poehlmann, 2005b). The child’s home may be different from the environment in which he or she lived prior to the parent’s incarceration because of changes in caregivers and economic disruption (Arditti, Lambert-Shute, & Joest, 2003). Child characteristics such as age are also important. In their analysis of 2007 national prisoner data, Glaze and Maruschak (2008) found that 22% of children with parents in state prison and 16% of children with parents in federal prison were four years of age or younger. Figures for 1989 showed that nearly 1% of U.S. children under four years of age had a parent in jail (Kemper & Rivara, 1993). These statistics suggest that many children experience parental incarceration while in the process of forming primary attachments.

Mesosystem factors

Also important are children’s mesosystems, defined as the connections that occur across microsystems (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). For children of incarcerated parents, the parent–caregiver relationship is a key mesosystem context. Positive parent–caregiver relationships are associated with more stability in children’s living arrangements when mothers are in prison, and relationship quality is related to parent–child contact as well (Poehlmann, Shlafer, Maes, & Hanneman, 2008). Yet micro- and mesosystem processes are not sufficient to capture the complex dynamics that occur at multiple contextual levels for children whose parents are incarcerated. Ecological theory highlights variables in the larger social context, including the exosystem (processes that occur in settings without the child but that still affect the microsystem), the macrosystem (the organization and ideals of the society and culture in which the child is embedded), and the chronosystem (time factors, including transitions) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

Exosystem factors

For children of incarcerated parents, multiple exosystem factors are critical, including parent and caregiver poverty, stress, supports available, and the gender of the incarcerated parent. It is caregivers who must handle children’s developmental, academic, and social issues on a day-to-day basis during parental incarceration (Hanlon, Carswell, & Rose, 2007). Caregivers are often economically disadvantaged people of color who must deal with chronic strains (Arditti et al., 2003). Consistent with our model, caregiver and child well-being appear to be linked in families with incarcerated parents (e. g., Poehlmann, Park, et al., 2008).

Regarding parent gender, the vast majority of children affected by parental incarceration have a father in prison or jail (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008; Kemper & Rivara, 1993). However, research indicates that children with incarcerated mothers may face comparatively greater stress and more cumulative risks in their environments than children of incarcerated fathers (Johnson & Waldfogel, 2002), including homelessness, mental and physical health problems (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008), and exposure to parental criminal activity (Dallaire & Wilson, 2010). The vast majority of children with incarcerated fathers live with their mothers during the incarceration period, whereas children with incarcerated mothers are more likely to live with their grandparents, other family members, or in foster care (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008).

Macrosystem and chronosystem factors

Macrosystem or structural factors, such as societal and judicial attitudes toward imprisonment and racial disparities in incarceration rates, are important considerations for children of incarcerated parents. Issues related to time and transitions, such as changes in policies and sentence lengths, are important chronosystem factors.

Changes in policies over time have resulted in growing U.S. prison and jail populations. Incarceration rates rose dramatically during the 1980s and 1990s largely as a result of policies designed to “get tough” on drug offenders (Austin & Irwin, 2001; Hagan & Coleman, 2001; The Sentencing Project, n.d.). These policies resulted in an unprecedented reliance on incarceration, disproportionately affecting poor and minority individuals and families (Western & Wildeman, 2009). In 2007, Black children were 7.5 times more likely to have an incarcerated parent than were White children (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008). Racial disparities are even greater when one examines estimates of cumulative risk for having an incarcerated parent during childhood (Wildeman, 2009). Additional factors at the macrosystem level include differences in local, state, and federal visitation policies and the interface between the corrections, child welfare, and legal systems. Glaze and Maruschak (2008) found that 10.9% of imprisoned mothers and 2.2% of imprisoned fathers had a child in foster care, which has implications for parent–child contact.

The type of correctional facility and the facility’s policies impact children’s experiences of contact with their incarcerated parent. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010), jails are locally operated correctional facilities that confine persons before or after adjudication. Sentences to jail are usually one year or less (typically for misdemeanors), whereas sentences to state prison are generally more than one year (typically for felonies), although this varies by state. Six states (Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, Delaware, Alaska, and Hawaii) have an integrated correctional system that combines jails and prisons (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010). Compared with prisons, jails are often located closer to the incarcerated individual’s family members, possibly affecting visitation frequency. Compared with state prisons, there are fewer federal prisons; federal prisoners are under the legal authority of the U.S. federal government (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010), and federal prisons are often located far from the incarcerated individual’s family.

National Trends Regarding Children’s Contact With Incarcerated Parents

Although the majority of imprisoned parents have some contact with their children during the incarceration period, mail contact is much more common than visitation (Maruschak, Glaze, & Mumola, in press). A 2007 survey of state and federal prisoners in the United States revealed that more than three quarters of incarcerated parents had mail contact with their children (52% reported at least monthly mail contact) and more than half had phone contact (38% reported at least monthly phone calls). In contrast, only 42% of state and 55% of federal prisoners had visits with their children during incarceration (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008). Comparable national statistics are not available for jailed parents, although results from smaller samples suggest considerable variation in levels of parent–child contact during parental jail stays (e.g., Arditti, 2003).

In our theoretical model, visitation between children and incarcerated parents is seen as the most proximal form of contact, and thus it may have the greatest effects on children’s attachment relationships and well-being. However, when children talk on the phone with or engage in written correspondence with their incarcerated parents, these experiences become part of the child’s proximal context as well. In addition, multiple levels of contextual influence affect children’s proximal experience of contact (see Figure 1). In the next section we summarize research focusing on factors at each of these contextual levels in relation to parent–child contact.

Recent Research Focusing on Parent-Child Contact

Studies assessing incarcerated parent–child contact that have been conducted since 1998 are summarized in Table 1. When we began writing this review in 2008, we decided to focus on the literature that has emerged during the past decade because (a) there has been a dramatic increase in the proportion of racial and ethnic minority individuals with low education levels (see Western & Wildeman, 2009) and of women (Mumola, 2000) who are incarcerated; (b) overcrowding in prisons and jails resulting from increased populations has led to proportionally fewer dollars being spent on rehabilitation efforts (e.g., parenting and visitation programs), more crowded visiting environments, and inmates sometimes being sent to facilities in different states, which may affect visitation; and (c) advances in technology have increased the use of closed-circuit TV visits and other alternatives (e.g., video). Because of these issues, findings with samples collected earlier than 1998 may not be as relevant for this area of scholarship.

Table 1.

Studies Assessing Contact Between Incarcerated Parents and Their Children (Conducted Since 1998)

| Author(s) | Group(s) sampled | Age of children | Sample size | Parent incarcerated |

Findings related to parent child contact | Study ratinga |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact associated with positive child outcomes (mean study rating of 7.0) | ||||||

| Block & Fbtthast (1998)b | Mothers, children, caregivers |

7–17 years | 35 mothers, 32 daughters, 22 caregivers in Girl Scouts Beyond Bars (GSBB) |

Mother in MD state prison |

Mothers in intervention received more visits from their daughters per year than matched group; caregivers described some decrease in girls’ problems following participation in GSBB |

4 |

| Byrne, Goshin, & Jsestl (2010)b | Mothers, children | 2–16 months | 30 | Mother in NY state prison nursery program |

Infants who participated in the prison nursery intervention with their mothers for at least one year were more likely to have secure attachments than infants discharged from the nursery program earlier |

11 |

| Dallaire, Wilson, & Ciccone (2010)c | Children, caregivers |

4–14 years | 32 | Father and/ or mother in VAjail |

More letters were associated with less child depression and somatic complaints |

6 |

| Dallaire, Ciccone, & Wilson (2010)d | Teachers | 6–18 years | 30 | Father and/ or mother in VAjail or prison |

Teachers noted benefits of mail correspondence for children with incarcerated parents |

5 |

| Landreth & Lnbaugh (1998)b | Fathers, children | 4–9 years | 16 intervention, 16 control |

Father in federal prison |

Child self-esteem increased following participation in visitation program, although too many child participants dropped out of intervention to make group comparisons |

6 |

| Shlafer & Fbehlmann (2010)b | Children, caregivers |

4–15 years | 57 | Father and/ or mother in Wl prison |

Children who had contact with their incarcerated parents reported fewer feelings of alienation toward that parent compared with children who had no contact (visits, calls, letters not differentiated); contact not related to children’s behavior problems |

9 |

| Trice & Brewster (2004) | Mothers, caregivers |

13–19 years | 58 | Mother in VA state prison |

More frequent contact (visits, calls, letters not differentiated) with incarcerated mothers associated with less child school drop outs and suspensions |

8 |

| Contact associated with positive parent or caregiver outcomes (mean study rating of 8.2) | ||||||

| Carlson (1998)b | Mothers | Infants (months not reported) | 24 | Mother in NE prison nursery program |

Recidivism was lower for the mothers in the nursery program compared with mothers who were incarcerated prior to implementation of the nursery program |

6 |

| Houck & Loper (2002) | Mothers | Birth 20 years | 362 | Mother in VA state prison |

More contact with children was associated with less maternal distress |

7 |

| LaVigne, Naser, Brooks, & Castro (2005) | Fathers | Under 18 years | 142 | Father in IL state prison |

More visits and mail correspondence with children during incarceration predicted more paternal involvement with children following the father’s release from prison |

6 |

| Landreth & Lobaugh (1998)b | Fathers, children | 4–9 years | 16 intervention, 16 control |

Father in federal prison |

Fathers in the visitation intervention reported less parenting stress and more acceptance of the child |

6 |

| Loper, Carlson, Levitt, & Scheffel (2009) | Mothers, fathers | Birth 20 years | 211 | Mother or father in TX or OH state prison |

More mail contact associated with lower parenting stress for mothers; stronger alliance between caregiver and incarcerated parent associated with more mail contact and phone calls with children |

12 |

| Fbehlmann (2005a) | Mothers | 2 – 7 years | 94 | Mother in Wl state prison |

More phone calls associated with maternal perceptions of more positive motherlchild relationships; more visits associated with fewer maternal depressive symptoms |

12 |

| Snyder, Carlo, & Coats Mullins (2001)b | Mothers | 1 – 16 years | 31 intervention, 27 wait list |

Mother in Midwestern state prison |

Mothers in the intervention group reported more mail and phone contact with children and more positive perceptions of the mother child relationship |

8 |

| P. J Thompson & Harm (2000)b | Mothers | Infancy 32 years | 104 intervention |

Mother in AR state prison |

Mothers reported improvement in empathy and parenting attitudes following intervention, but only when they received frequent visits from children |

6 |

| Contact associated with positive parent or caregiver outcomes (mean study rating of 8.2) | ||||||

| Tuerk & Loper (2006) | Mothers | Birth 21 years |

357 | Mother in VA state prison |

More frequent letter writing (not visits or phone calls) associated with less maternal distress regarding parenting competence |

11 |

| Contact associated with negative child outcomes (mean study rating of 8.0) | ||||||

| Dallaire, Wilson, & Ciccone (2009)c | Children, caregivers |

4–14 years |

32 | Father and/ or mother in VA jail |

More visits with jailed parent associated with children’s insecure attachment |

7 |

| Dallaire, Wilson, & Ciccone (2010)c | Children, caregivers |

4–14 years |

32 | Father and/ or mother in VA jail |

More visits with jailed parent associated with more child attention problems |

6 |

| Dallaire, Ciccone, & Wilson (2010)d | Teachers | 6–18 years |

30 | Father and/ or mother in VAjail or |

Teachers noted negative changes in children’s behaviors following visitation with incarcerated parents |

5 |

| Poehlmann (2005b) | Children, caregivers, mothers |

2.5 – 7.5 years |

60 | Mother in Wl state prison |

Recent visit with mother associated with children’s insecure attachment; letters and phone calls not examined because of young age of children |

13 |

| Shlafer & Fbehlmann (2010)b | Children, caregivers |

4–15 years |

57 | Father and/ or mother in Wl prison |

Some children reported feeling unsure about whether or not they wanted to see or have contact with the incarcerated parent; of the children who discussed their experiences visiting the incarcerated parent, none reported positive visitation experiences |

9 |

| Contact associated with negative parent or caregiver outcomes (mean study rating of 9.0) | ||||||

| Arditti (2003)d | Caregivers | Not reported |

56 | Father or mother in jail in mid-Atlantic state |

Descriptions of caregivers’ concerns about noncontact visits; lack of child- friendly space; harsh and disrespectful treatment by staff; long waits; 77.8% of caregivers who brought their children indicated that the no-contact part of the visit was a serious problem |

8 |

| Bales & Mears(2008) | Administrative data (Department of Corrections) |

Not reported | 7,000 | Incarcerated individual in FL corrections |

More child visits associated with increased recidivism; more spousal visits associated with decreased recidivism |

9 |

| Casey-Acevedo, Bakken, Karle (2004) | M others | Under 18 years |

158 | Mother released from state prison |

Mothers who received child visits were more likely to engage in violent or serious disciplinary infractions during incarceration, whereas women who did not receive child visits were more likely to commit no infractions or minor ones |

10 |

| Poehlmann, Shlafer, & Maes (2006)c,d | Caregivers | 2.5 – 7.5 years |

60 | Mother in Wl state prison |

Caregivers did not know how to handle children’s behavior issues that occurred before and after visits |

9 |

| Descriptive study or study examined predictors of contact frequency (mean study rating of 9.8) | ||||||

| Arditti & Few (2008)d | Mothers | 1.5 – 27 years |

10 | Mother in VA corrections or probation |

Descriptions of children’s distress during visits; children’s visits 3ended to be uncertain and bittersweeO(p. 8) |

9 |

| Arditti & Few (2006)d | Mothers | Mean of 11 years; range not reported |

28 | Mother released from VA jail or prison |

Descriptions of mothers’ problems with visits and reports of what was discussed with caregivers; majority of women thought visits were too short to emotionally connect with children |

7 |

| Arditti, Lambert-Shute, & JOest (2003) | Caregivers | Not reported | 56 | Father or mother in jail in mid-Atlantic state |

Family members visiting the jail tended to be economically disadvantaged; many had health concerns, emotional stress, parenting strain |

8 |

| Arditti, Smock, & Farkman (2005)d | Fathers | Mean of 10 years; range not reported |

51 | Father in minimum security prison in UT or OR |

Themes of lost contact with children and lost paternal identity |

11 |

| Day, Acock, Bahr, & Arditti (2005)d | Fathers | Not reported | 51 | Father in UT or OR state prison |

Men had very few contacts with children, but most men reported feeling close or very close to the child |

7 |

| Casey-Acevedo & Bakken (2002) | Mothers | Under 18 years |

158 | Mother in maximum security prison in a northeastern state |

Younger mothers were more likely to receive visits from their children than were older mothers |

7 |

| Enos(2001)d,e | Mothers | 6 months – 21 years |

25 | Mother in R prison | Caregivers often regulated contact between incarcerated mothers and children; relationships between mothers and caregivers important for contact |

7 |

| Glaze & Maruschak (2008) | Fathers, mothers | Under 18 years | 14,499 state prisoners and 3,686 federal prisoners |

Farent in state or federal prison |

Mothers in state prison reported more phone and mail contact with children but equal levels of visits compared with fathers; the longer the parents were incarcerated, the less likely they were to have weekly child contact |

13 |

| JOhnson & Waldfogel (2002) | Fathers, mothers | Under 18 years |

13,000 to 17,000 prisoners |

Farent in state or federal prison |

Frequency of incarcerated parentl child contact decreased between 1991 and 1997 |

12 |

| Maruschak, Glaze, & Mumola (in press)e | Fathers, mothers | Under 18 years |

14,499 state prisoners and 3,686 federal prisoners |

Farent in state or federal prison |

The longer the parents were incarcerated, the less likely they were to have weekly child contact |

13 |

| Mumola (2000) | Fathers, mothers | Under 18 years |

10,403 | Farent in state or federal prison |

In state prisons, more mothers than fathers had at least monthly phone or mail contact with children. More than half of parents in state prisons received no child visits |

13 |

| Poehlmann, Shlafer, Maes, & Hanneman (2008) | Mothers | 2.5 – 7.5 years |

92 | Mother in Wl state prison |

Children had more frequent visits and phone calls with their mothers when motherlcaregiver relationships were warm, close, and loyal |

12 |

| Roy & Dyson (2005)d | Fathers | Not reported | 40 | Father in IN work-release program |

Mothers of children functioned as gatekeepers of contact with incarcerated fathers |

6 |

| Swisher & Waller (2008) | Mothers | Birth 3 years | 1,002 | Nonresident father had past, current or no time in jail |

Currently jailed fathers saw their children less than other nonresident fathers; this was less pronounced for Black fathers than White fathers |

12 |

| Tewksbury & DeMichele (2005) | Visitors to the corrections facility |

Not reported | 113 visitors with children; of these, 77 children visited |

Medium-security facility in KY; parental gender not reported |

Description of visitation experience and rating of visitation environments; no significant differences between visitation experiences for those who brought children and those who did not; unclear if child visitor was inmate’s child or not |

11 |

Note. Table is organized by study findings (contact and positive or negative child or adult outcomes; study descriptive only or study examined predictors of contact). Within each section, studies are listed in alphabetical order by first author. Studies are listed in more than one section when findings differed by type of contact or child/adult outcomes.

Methodological rigor rated according to the criteria shown in the Appendix.

Children or parents were involved in an intervention.

The study was unpublished.

The study was primarily qualitative.

The study was reported in a book or book chapter.

To identify the studies reviewed, we searched nine databases (PsycINFO, PsycArticles, ProQuest Research Library, Web of Knowledge/Web of Science, Social Sciences Full Text, SocINDEX, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, Sociological Abstracts, and Google Scholar), searched the reference lists of articles focusing on children of incarcerated parents, and contacted researchers who work in this area to locate unpublished data as well as data presented at conferences. We included both quantitative and qualitative studies in our review. Table 1 summarizes the studies according to the findings (positive outcomes for children or caregivers, negative outcomes for children or caregivers, or descriptive).

As an indication of methodological rigor, we rated the studies with regard to sampling procedures, response rates, sample size, inclusion of covariates such as poverty, attention to children’s age, measurement quality, and the publication outlet (see the Appendix for coding and interrater reliability data). Ratings of the 36 studies ranged from 4 to 13, with a mean of 8.6 (SD 5 2.6). Of the studies reviewed, 8.3% were unpublished. We had hoped to use these ratings to clarify research findings when results about parent–child contact were mixed or contradictory. However, the mean ratings of studies finding positive versus negative associations between contact and child or adult outcomes did not differ, t(23) 5 0.72, ns. Thus, variables other than methodological rigor appeared to be responsible for the mixed findings, as we discuss later.

Microsystem Factors in Relation to Contact

Child attachment and parent perceptions of the relationship

No published studies have reported direct, systematic observations of children’s attachment behaviors during visits between incarcerated parents and their children, in part because of the logistical difficulties in recording such behaviors in prison and jail settings. Thus, the studies reviewed relied on representational (symbolic instead of behavioral) assessments of children’s attachments with incarcerated parents, or they measured parental perceptions of the parent–child relationship.

Several studies (Dallaire, Wilson, & Ciccone, 2009; Poehlmann, 2005b; Shlafer & Poehlmann, 2010) assessed children’s attachment representations in relation to their experiences of contact with parents in prison or jail using methods such as the Attachment Story Completion Task (Bretherton, Ridgeway, & Cassidy, 1990), the Family Drawing procedure (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy 1985), or self-report measures of attachment security (e.g., the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment; Armsden & Green-berg, 1987). Poehlmann (2005b) and Dallaire et al. (2009) found associations between visits with parents in corrections facilities and representations of insecure attachment relationships in children ranging from 2.5 to 14 years of age. In both of these studies, the visitation environments were described as not child friendly.

One explanation for these findings is that the quality of visits is likely affected by the institutional settings, which vary from child friendly to highly stressful, thus potentially affecting children’s attachment security. Another explanation for these findings is that a recent visit may activate the child’s attachment system, including eliciting signs of distress and anxiety, without affording opportunities to work through intense feelings about the relationship with the parent because the parent–child separation continues following the visit (Poehlmann, 2005b).

Although visits may be stressful when visiting environments are not child friendly, lack of any contact with incarcerated parents also may be associated with children’s negative feelings about their incarcerated parents. For example, in a study of children who participated in a mentoring program for children of incarcerated parents, Shlafer and Poehlmann (2010) found that for the 24 children (age nine and older) who rated their relationships, experiencing no contact with the incarcerated parent was associated with children’s feelings of alienation from the parent. However, there was no relation between children’s feelings of trust or communication and contact with the incarcerated parent. In qualitative analyses of interviews with children, Shlafer and Poehlmann also found that some children reported feeling unsure about whether they wanted to see or have contact with the incarcerated parent. Children who discussed their experiences visiting the incarcerated parent did not report positive visitation experiences.

Table 1 indicates that the methodological rigor ratings of the studies assessing contact and child attachment ranged from 7 to 13. The studies with higher (13) (Poehlmann, 2005b) and lower (7) (Dallaire et al., 2009) ratings documented negative associations between visitation and child attachment, whereas the study rated in the average range (9) (Shlafer & Poehlmann, 2010) found that no parent–child contact was associated with children’s feelings of alienation. Because the index of methodological rigor does not resolve the contradictory findings, we suggest examining other variables that differed in the studies: quality of parent–child interactions during visits, whether an intervention occurred, type of contact, and children’s age.

As a key proximal process, the quality of parent–child interaction during a visit likely influences children’s reactions to the visit. Intervention efforts often focus on increasing the quality and frequency of parent–child interactions. It is important to note that four of the seven studies finding benefits of contact for children involved interventions (e.g., visitation programs, prison nursery intervention), whereas only one of the five studies finding negative associations between contact and child outcomes involved an intervention. Moreover, of the seven studies focusing specifically on visits and child outcomes, only studies that involved interventions showed benefits of visitation for children. For example, in one examination of a parenting intervention for 16 fathers incarcerated at a federal correctional facility and their young children, Landreth and Lobaugh (1998) found that children’s self-esteem increased across a 10-week intervention. A key component of this intervention was a weekly parent–child visit in which the fathers could interact and have physical contact with their children in a child-friendly environment.

Additional studies examined contact in relation to parental perceptions of the parent–child relationship, rather than assessing the child’s attachment or other direct indicators of child well-being. These studies generally found positive associations between contact and parental relationship perceptions. For instance, in a study focusing on imprisoned mothers, Poehlmann (2005a) found that more telephone calls, but not visits, related to positive maternal perceptions of relationships with children. In addition, several studies examined the effects of interventions designed to increase contact between incarcerated parents and their children in child-friendly settings and found positive effects of such contact for incarcerated parents (e.g., Snyder, Carlo, & Coats Mullins, 2001).

It is also possible that effects of contact on the parent–child relationship are more apparent following the parent’s release from prison. LaVigne, Naser, Brooks, and Castro (2005) interviewed 142 fathers during incarceration and postrelease and found that more frequent visits and mail correspondence with children during incarceration were related to more parental involvement with the child in the months following prison release.

Child age and contact

Children’s age is an important microsystem factor when considering parent–child contact during parental incarceration. To our knowledge, no published studies have assessed contact between incarcerated parents and their infants and toddlers living in the community. Infants need frequent contact with a care-giver to form an attachment relationship with that individual (Bowlby, 1982) and, to state the obvious, infants are unable to talk on the phone and write or read letters. The need for mother–child contact during the newborn and infancy periods has been acknowledged in a few progressive jails and prisons with nursery programs in which incarcerated mothers are permitted to have extended contact or live with their newborns and infants. For instance, the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women in New York has, since 1901, allowed incarcerated mothers to live with their newborns for the child’s first year, and an evaluation of infant–mother attachment in the Bedford Hills program was recently completed (Byrne, Goshin, & Joestl, 2010). Byrne et al. found that infants who resided with their mothers in the prison nursery intervention program for at least one year were more likely to have secure attachments to their mothers than were infants discharged from the nursery program prior to one year. Also, the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women has allowed mothers to live with their newborn infants since 1994. Though child outcomes were not examined, Carlson (1998) reported that the 24 women who participated in this program were less likely to be readmitted to prison (5% recidivism rate) than were a group of women who gave birth while incarcerated prior to implementation of the prison nursery program (these women had a 17% recidivism rate).

Child age may affect children’s experiences of visits and other forms of contact, and it may determine how much control caregivers have regarding children’s contact with incarcerated parents. For young children, caregivers often function as gatekeepers of children’s contact (Enos, 2001). Whereas some caregivers of young children support the parent–child relationship by fostering contact, other caregivers limit contact. When children are young, caregivers’ responses to children’s behavioral reactions to visits with incarcerated parents are critical factors as well (Arditti et al., 2003). Young children may need emotional support and reassurance within the microsystem setting to cope effectively with the prison or jail setting so that the experience functions as a means of strengthening parent–child relationships rather than as a source of stress.

As children grow older, however, they may have contact with their incarcerated parents that is not regulated by caregivers but is facilitated by other family members. For example, some adolescents in Shlafer and Poehlmann’s (2010) study reported that they had contact with the incarcerated parent without the caregiver’s knowledge. As children develop, they may also express their opinions about contact because of advances in verbal skills (Shlafer & Poehlmann, 2010).

Child behavior problems and contact

The ways in which children’s behaviors with others (e.g., caregivers, teachers, peers) relate to contact with the incarcerated parent constitute another important microsystem process. Several studies examined children’s behavior problems and school functioning in relation to contact with incarcerated parents, with mixed findings. In a study of 58 adolescents with incarcerated mothers, Trice and Brewster (2004) found that more mother–child contact (a combination of phone calls, visits, and letters) was associated with fewer instances of school dropout and suspensions from school for the adolescents. In contrast, Dallaire, Wilson, and Ciccone (2010) found that children of jailed parents reported more attention problems when they visited more often with the parent. However, children also reported fewer anxious/depressed and somatic complaints when they had more mail correspondence with the jailed parent. Shlafer and Poehlmann (2010) found no statistically significant association between children’s contact with incarcerated parents and caregiver- and teacher-reported behavior problems. However, they did not differentiate among types of contact. A study examining the Girl Scouts Beyond Bars intervention, which includes an enhanced visitation component, found that nearly all caregivers interviewed reported some decrease in girls’ problem behaviors following the intervention (Block & Potthast, 1998).

Table 1 indicates that our methodological rigor ratings were similar across studies focusing on contact in relation to child behavior issues and school functioning (ratings ranged from 4 to 9). Rather than reflecting a difference in study quality, perhaps these mixed findings reflect variations in the assessment of contact used, underscoring the importance of differentiating among types of parent–child contact in relation to child outcomes.

To further examine different types of parent–child contact and children’s school functioning, Dallaire, Ciccone, and Wilson (2010) conducted interviews with 30 teachers who described the behaviors of children with incarcerated parents and conducted qualitative analysis of the interviews. Teachers said that following a weekend when children had visited their incarcerated parents, the children had trouble concentrating when they returned to school. The teachers also made several positive comments about mail correspondence between incarcerated parents and children. For example, one teacher mentioned that a child in her class often sent her incarcerated mother pictures and letters. The teacher felt that this correspondence with the incarcerated mother was positive because it gave the child an opportunity to share her private thoughts and feelings with her mother. In addition, when the mother wrote back, the child had something tangible to hold on to or refer to when she felt sad or was missing her mother.

It should also be noted that there are likely bidirectional associations between children’s behavior problems and contact. Children visiting their parent at a jail or prison may on occasion present with behavioral and emotional difficulties (Arditti & Few, 2006) that can exacerbate an already tenuous visiting environment and impact the quality of parent–child interaction during the visit.

Mesosystem Factors in Relation to Contact

The relationship that is formed and maintained between incarcerated parents and children’s caregivers represents a key mesosystem factor. Communication and shared perceptions about child rearing and contact issues are also included in the mesosystem.

Several studies found that the quality of the relationship between the incarcerated parent and the child’s caregiver was associated with frequency of child contact (Enos, 2001). For example, in an analysis of interviews with 92 incarcerated mothers with young children, Poehlmann, Shlafer, et al. (2008) found that children visited and spoke on the phone with their incarcerated mothers more frequently when mother–caregiver relationships were characterized by warmth, closeness, and loyalty. Loper, Carlson, Levitt, and Scheffel (2009) used a modification of the Parenting Alliance Measure (PAM; Abidin & Konold, 1999) to assess the perceived convergence between the imprisoned parent and the child’s caregiver regarding co-parenting issues. They found that imprisoned mothers and fathers perceiving stronger coparenting alliances were more likely to experience child contact (letters in particular). Other studies focusing on incarcerated mothers and using different methods found similar results (e.g., Enos, 2001).

Although parental perceptions of the alliance with the caregiver are important, these perceptions may not necessarily be the same as the caregivers’ perceptions regarding contact issues or the parents’ relationship with the child. Tuerk (2007) also queried incarcerated mothers and caregivers regarding the average levels of contact that they had with each other to discuss child issues. Incarcerated mothers consistently estimated higher levels of such contact than did children’s caregivers. Day, Acock, Bahr, and Arditti’s (2005) interviews with fathers at minimum security prisons in Utah and Oregon indicated that although the men had experienced very few contacts with their children, 32 of the 51 men interviewed said that they felt close or very close to their children. It is possible that incarcerated parents may perceive more contact and positive relationships with family members than do the family members themselves.

Exosystem Factors in Relation to Contact

Several exosystem factors impact (and are impacted by) the quality and frequency of parent–child contact during parental incarceration. Family socioeconomic resources, the characteristics of incarcerated parents (e.g., gender), and parent and caregiver stress during the incarceration period appear interrelated with parent–child contact.

Family socioeconomic resources and contact

Economically stressed families face challenges in arranging contact between children and incarcerated parents. The distant location of the prison or jail and the high cost of transportation and long-distance calls are key barriers (e.g., Banauch, 1985; Bloom & Steinhart, 1993; Myers, Smarsh, Amlund-Hagen, & Kennon, 1999). State prisons are often located 100 or more miles from the urban settings in which most of the prisoners’ families live, and federal prisons are typically located even farther from families. Moreover, many prisons and jails only allow collect calls from incarcerated individuals, and receivers are often charged extraordinarily high rates for such calls. Thus, children in families with fewer socioeconomic resources may experience difficulty staying in contact with their incarcerated parents. Poehlmann, Shlafer, et al., (2008) found that imprisoned mothers with more pre-incarceration socioeconomic risks such as unemployment, young age, single marital status, and low education were less likely to receive visits from children during the incarceration. Christian and colleagues (Christian, 2005; Christian, Mellow, & Thomas, 2006) examined the social and financial costs to families of maintaining ties to their imprisoned family members during the time of incarceration in state prison facilities in New York. They conservatively estimated that the family members, who resided in a particular neighborhood in the Bronx, spent at least 15% of their monthly incomes to stay in contact with the incarcerated family member.

Parental gender and contact

In a 2007 national survey of state and federal prisoners, imprisoned mothers more frequently reported at least monthly phone calls (47% vs. 38%) and mail correspondence with children (65% vs. 51%) than did imprisoned fathers (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008). However, no gender differences in frequency of visits with children emerged. Other studies likewise reported lower levels of contact between children and their incarcerated fathers than between children and their incarcerated mothers (e.g., Loper et al., 2009).

Caregiver stress and contact

The stress experienced by the child’s caregiver represents another contextual feature that relates to contact. Often caregivers must arrange transportation to the jail or prison, pay for phone calls to and from the corrections facility, and cope with children’s behaviors related to separation from and contact with parents (Cecil, McHale, Strozier, & Pietsch, 2008). Shlafer and Poehlmann (2010) conducted a qualitative analysis of caregivers’ responses to questions about children’s contact with incarcerated parents during monthly interviews (across 6 months). Caregivers expressed both positive and negative feelings about children’s visitation and phone contact with incarcerated parents. Although many caregivers wanted the child to have contact with the incarcerated parent, most caregivers worried that such contact might have detrimental effects on the child. Some caregivers said that they limited contact because of perceived behavioral changes, citing children’s confusion, frustration, and upset following visits and phone conversations with the incarcerated parent.

To better understand the caregiving context for behavioral difficulties associated with visitation, Poehlmann, Shlafer, and Maes (2006) examined caregivers’ reports of how they handled young children’s behaviors prior to, during, and after visits with imprisoned mothers. Qualitative analyses of interviews revealed that caregivers often did not know how to support children around visitation issues. Caregivers perceived children’s behaviors prior to and following visits as a source of stress and as a barrier to facilitating the mother-child relationship.

Parental stress and contact

Whereas care-givers’ stress may result in their limiting children’s visits and other forms of contact, difficulties in maintaining contact with children may result in distress for incarcerated parents. Interviews with imprisoned fathers have revealed themes related to lost contact with children and paternal identity confusion (Arditti, Smock, & Parkman, 2005; Clarke et al., 2005; Magaletta & Herbst, 2001; Roy & Dyson, 2005). Women likewise suffer pain associated with loss of child contact (Arditti & Few, 2008). For example, drawing on interviews with 56 women in a county jail, Hairston (1991) found that most jailed mothers regarded separation from children as the most difficult aspect of confinement.

Quantitative studies have likewise documented linkages between low levels of parent–child contact and parental distress. Houck and Loper (2002) reported that women who experienced more child contact were less likely to report symptoms of depression and anxiety during imprisonment. Similarly, Poehlmann (2005a) found that more visits from young children were related to less depression in 94 mothers in state prison. In their study of 211 mothers and fathers incarcerated in state prisons, Loper et al. (2009) found that mothers who had lower levels of phone and mail contact with children experienced higher levels of parenting stress. However, it is unclear whether such parental distress is related to quality of contact with children.

Parental disciplinary infractions and contact

Although incarcerated parents appear to experience more stress and depression when they experience less child contact, visits may be associated with some degree of emotional upheaval as well (Arditti, 2003). For example, in a review of prison records for 158 mothers recently released from state prison, Casey-Acevedo, Bakken, and Karle (2004) found that mothers who received child visits during the prison stay were more likely to engage in violent or serious disciplinary infractions during the incarceration period, whereas women who did not receive child visits were more likely to commit no infractions or minor ones (contrary to the authors’ hypotheses). Casey-Acevedo and colleagues suggested that although visits can be associated with joy and relief, they can also lead to feelings of upset and anger at the lack of control mothers have regarding their children’s lives.

Macrosystem Factors in Relation to Contact

Multiple and complex macrosystem factors affect parent–child contact during parental incarceration, including the interface between the child welfare and corrections systems and corrections policies regarding visitation. Although corrections environments are considered part of the child’s exosystem, we discuss these issues here because they are determined by policies.

Child welfare policies and legal issues

In general, courts and child welfare systems implement laws that attempt to strike a balance between the rights of parents and the best interests of their children. For incarcerated parents with children in foster care, that balance has become more precarious since enactment of the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA, 2000). Although ASFA requires “family service agencies to make ‘reasonable efforts’ to reunify parents and families” (Holtz, 2007, p. 294), it does not define “reasonable efforts” (Conway & Hutson, 2007, p. 214). Thus, interpretation of “reasonable efforts” is left up to each state’s courts and family service agencies. At the same time, ASFA “encourages placing children with adoptive resources that could eventually lead to permanent placement” (Holtz, 2007, p. 294) and mandates commencement of proceedings to terminate parental rights once a child has been in foster care for 15 out of the most recent 22 months (ASFA, 2000). Some scholars see passage of ASFA as a shift in child welfare policy away from an emphasis on family reunification for incarcerated parents and toward termination of parental rights and adoption (Genty, 2003, 2008; Nicholson, 2006). Parent–child contact during the child’s placement is a key factor when ASFA’s timelines are being considered.

When a child is in foster care and the parent is in prison or jail, multiple barriers exist regarding facilitation of parent–child contact (Allard & Lu, 2006). in part because of the lack of coordination between systems (de Haan, in press). However, national statistics indicate that far fewer children with an incarcerated parent live in foster care than live with the other parent or another relative (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008). These statistics suggest that most decisions about a child’s contact with an incarcerated parent are made by an individual family member rather than by a children’s court judge or social worker, both of whom would be required to consider the concurrent ASFA goals of reunification and permanence. When called upon to resolve intrafamilial disputes that may arise about contact between an incarcerated parent and a child, family law courts seek to determine the conditions, frequency, and type of contact that will be in the child’s best interest. In all jurisdictions, the standard by which courts determine which of the parents will be awarded custody, including placement and visitation, is known as the “best interests of the child” standard (Balnave, 1998). Although judges are certainly guided by their states’ relevant laws and precedent, a “best interest” determination is inherently subjective. In the case of an incarcerated parent, such a decision is also usually final, at least until the parent’s release from incarceration, because the appeal of a custody or visitation order is extremely difficult for an unrepresented inmate and, in any event, has a low likelihood of success.

Correctional facility visitation policies

A key correctional policy decision relates to whether to allow “full” contact visits, where physical contact is allowed; “open” but noncontact visits that occur without a physical barrier; or “barrier” visits, which occur through or across a barrier such as Plexiglas (see Johnston, 1995). Such policies typically reflect differences in institutional security levels and concerns for the safety of visitors (Sturges & Hardesty, 2005).

Policies at jails and federal and state prisons affect the level and type of contact children can have with the incarcerated parent. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons (n.d.), when visiting a federal prison facility, “in most cases, handshakes, hugs, and kisses (in good taste) are allowed at the beginning and end of a visit” (para. 3). Most federal facilities allow some type of contact between the incarcerated individual and the visitor. To determine the level of contact allowed during visitation at state prisons, we obtained information about state prison policies and procedures in 10 states (see Table 2). We chose these states to represent all of the major geographical regions in the United States. Many of the state facilities that we surveyed had guidelines similar to those outlined by the Federal Bureau of Prisons limiting contact to an embrace at the start and end of a visit. In addition, we examined visitation and contact policies in local and regional jails in major cities and counties in the same 10 states (see Table 2). County, city, and regional jails are often located in closer proximity to inmates’ homes and families than are state or federal prisons, thus making opportunities to visit with a jailed parent relatively feasible. However, we found that jails appear less likely than prisons to offer opportunities for physical contact between incarcerated parents and their children. It should also be noted that for visitors to some jails, visits occur through a closed-circuit television transmission in which the visitors are in a separate area of the jail. In these types of visitation situations, children do not have the opportunity to actually see their incarcerated parents other than on the television screen.

Table 2.

Visitation Policies at State Prisons and City/County/Regional Jails in 7 0 States

| State | No. of state prisons surveyed (% of prisons in state) |

% of state prisons with contact visits for general prisoners |

% of state prisons with contact visits for maximum security prisoners |

City/ county of jails surveyed | Type of jail visitation permitted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 18 (100%) | 100% | 0% | Phoenix/ Maricopa County |

Noncontact closed-circuit TV |

| Tucson/ Pima County | Noncontact closed-circuit TV | ||||

| Florida | 60 (95%) | 100% | 100% | Tallahassee/ Leon County Orlando/ O range County |

Noncontact closed-circuit TV Noncontact barrier |

| Louisiana | 9 (81%) | 100% | 0% | New Orleans/ Orleans Pa ris h |

Noncontact barrier |

| Baton Rouge/ E. Baton Rouge Pa rish |

Noncontact barrier | ||||

| M assachusetts | 13 (100%) | 82% | 0% | Boston/ Suffolk County North Hampton/ Hampshire County |

Noncontact barrier Contact visits |

| Michigan | 38 (100%) | 100% | 0% | Detroit/ Wayne County Lansing/ Ingham County |

Noncontact barrier Noncontact barrier |

| Nebraska | 9 (90%) | 100% | 100% | Omaha/ Douglas County | Noncontact barrier; however, inmates can apply for contact visits |

| Lincoln/ Lancaster County | Noncontact closed-circuit TV | ||||

| Pennsylvania | 25 (100%) | 100% | 100% | Harrisburg/ Dauphin County |

Noncontact barrier visits; however, inmates can earn contact visitation privilege |

| Pittsburgh/ Allegheny County |

Both contact and noncontact barrier visits; determined by offense |

||||

| Virginia | 36 (92%) | 100% | 100% | Richmond/Henrico County |

Noncontact barrier; however, some inmates can earn monthly contact visitation |

| Fairfax/ Fairfax County | Noncontact barrier | ||||

| W ashington | 19 (90%) | 94% | 0% | Seattle/ King County Olympia/ Thurston County |

Noncontact barrier Noncontact barrier |

| Wisconsin | 19 (100%) | 95% | 100% | Madison/ Dane County | Noncontact barrier; however, Huber inmates can apply for contact |

| Milwaukee/Milwaukee County |

Noncontact barrier |

Note. We chose the 10 states listed in Table 2 so that we could represent all the major regions of the United States New England (MA), Mid Atlantic (PA, VA), South (FL, LA), Southwest (AZ), Pacific Northwest (WA), Midwest (MI, WI), and Central Plains (NE). At the time this article was revised (December 2009), the information about visitation policies pertained to the majority of inmates at these corrections facilities; however, some policies may have changed since that time.

Concerns about visitation policies and procedures

Several studies have documented incarcerated parents’ concerns about having their children visit them in prison or jail. Some of these concerns relate to correctional institutions’ visitation policies, visitation environments, or locations. For example, British incarcerated fathers expressed concerns about visitation in terms of transportation costs, concerns for the safety of their children, and lack of opportunities for more natural and comfortable interactions (Clarke et al., 2005). Along similar lines, Hairston (1991) found that a majority of the jailed parents she interviewed did not wish for a visit from their children because of concerns about transportation costs, visitation and security conditions, and worries that the visit would be emotionally upsetting for the children. Although longed for, child visits can be associated with emotional distress, uncomfortable and unfriendly visitation environments, and limited opportunities for meaningful contact (Arditti, 2003; Loper et al., 2009).

Corrections policies regarding visitation have a direct effect on the environments in which visitation between children and incarcerated parents occurs. During a visit, these environments become part of the child’s proximal context (see section on Microsystem Factors in Relation to Contact). Differences across visitation settings can affect the potential outcomes of contact and may explain some of the contradictory findings regarding the benefits of contact for family members.

For example, Houck and Loper (2002) found that higher levels of contact with children were related to less depression among imprisoned mothers, although in a subsequent study using similar measurement, no such association was evident (Loper et al., 2009). In the Houck and Loper (2002) study, incarcerated mothers were housed in a single facility where considerable attention was directed to providing child-friendly visitation opportunities, whereas the subsequent Loper et al. (2009) study drew incarcerated individuals from multiple institutions with more varied visitation environments. Some included child-centric areas, whereas others required Plexiglas barriers. These variations in visitation environments may affect contact experiences.

Similarly, Dallaire et al. (2009) linked more visits with insecure attachment patterns in children. However, the visits occurred through a Plexiglas barrier in a large, noisy room, and children and caregivers were sometimes frisked or patted down before being allowed into the visitors’ waiting room. Such experiences surrounding visitation may frighten children, thus negatively affecting their sense of security. This variability in the hospitality of visitation settings is typical across correctional settings (Hairston, 1996) and reflects largely unmeasured differences in institutional contact policies that may obfuscate patterns regarding the degree to which visits between incarcerated parents and children are beneficial to family members.

Alternatives to visitation

Because of such policies, visitation environments are not under the control of incarcerated individuals or families. However, remote forms of contact such as phone calls or written correspondence may offer a viable alternative for reliable contact between incarcerated parents and their children. Tuerk and Loper (2006) found that frequency of letter writing, rather than the frequency of personal visits or phone calls, accounted for the association between more child contact and less parenting stress. This general pattern was replicated in the Loper et al. (2009) study, in which incarcerated mothers who had frequent mail contact with children reported less distress regarding feelings of competence as a parent.

The potential benefits of remote forms of contact may be a reflection of the systems that affect healthy parent–child relationships. Fulfillment of the child’s need for “enduring forms of interaction in the immediate environment” (Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994, p. 572) may depend on mesosystem factors such as the parent’s own sense of parenting competency and skill as well as on exosystem factors such as the hospitality of the visitation setting. Letters and phone calls may remove some of the potentially negative aspects of visitation settings. Parents have control over the content of letters and can plan and anticipate what their children may need to hear in ways that are not available to them in a noisy or unpredictable visitation environment. Clarke et al. (2005) reported that the fathers in their study perceived letters and phone calls to be a more positive form of contact than visits because they provided an opportunity for a show of paternal commitment to their children’s welfare in a safe and controlled setting. The parent’s own sense of competency and devotion to the child may be better expressed in contexts that involve stability and control.

Chronosystem Factors in Relation to Contact

An important chronosystem factor involves how incarcerated populations change over time. During the past several decades in the United States, there have been significant increases in the rates of incarceration among certain demographic groups, including women, African Americans, and individuals of low socioeconomic status and low educational attainment (see Wildeman, 2009). The concentration of incarceration among impoverished, African American communities that has occurred in the United States over time may negatively affect children’s ability to stay in contact with their incarcerated parents because of limited resources in these families and communities (see section on Exosystem Factors in Relation to Contact). Indeed, a comparison of 1991 and 1997 national prisoner surveys indicated that all forms of contact between incarcerated parents and their children decreased significantly over time (Johnson & Waldfogel, 2002).

Another chronosystem factor related to parent–child contact involves the length of time that parents are incarcerated. Results of the 2004 U.S. national prisoner survey indicated that as the length of parents’ prison stays increased, the likelihood of having at least weekly contact with their children decreased (Maruschak et al., in press). This decline appeared to result from fewer parents reporting at least weekly mail contact with children (Maruschak et al., in press).

An additional chronosystem factor that is of great interest to families and society is whether incarcerated parents eventually return to prison or jail in the months or years following release. Carlson (1998) found reduced recidivism among mothers who participated in a nursery program that allowed continuous child–mother contact. However, this small-scale study involved a unique intervention that is distinctly different from that afforded during correctional visitation experiences. In an examination of linkages between recidivism and prison visitation, Bales and Mears (2008) reviewed visitation records of 7,000 Florida inmates and found that spousal visitation during incarceration was associated with decreased recidivism. However, the value of child visitation was questioned. Contrary to the authors’ hypotheses, there was no association between recidivism and the occurrence of any child visitation (when measured as a dichotomous variable), and more frequent child visits were associated with increased recidivism. The authors speculated that this finding may reflect the incarcerated parents’ own distress that may have occurred during visitation, and they recommended further study of the quality of the visitation context as a means to shed further light on the value of child visitation. The study also found that more visitation (of all types assessed) reduced recidivism for men only. It is possible that an unexamined interaction between the incarcerated individual’s gender and relationship to the visitor (e.g., spouse, child) affected the results.

Conclusions and Recommendations Regarding Contact and Future Research

Our review of the emerging research reveals that contact between children and their incarcerated parents depends on a number of interrelated factors at each systemic level. In addition, parent–child contact appears to affect certain contexts (e.g., parent and caregiver stress, children’s attachments), indicating bidirectional associations, as predicted by our model.

Overall, with only a few exceptions, studies have generally found benefits of child contact for incarcerated parents (82% of the studies listed in Table 1 that assessed parent outcomes), whereas the literature assessing child outcomes in relation to contact has yielded somewhat mixed findings (58% of the studies listed in Table 1 that assessed child outcomes found benefits). Studies focusing specifically on visits documented positive child outcomes when such contact occurred as part of an intervention (e.g., Byrne et al., 2010; Landreth & Lobaugh, 1998) and found negative outcomes when such contact occurred in the absence of intervention (e.g., Dallaire et al., 2009; Poehlmann, 2005b). In contrast, studies documented benefits of mail contact even when interventions were not in place (e.g., Dallaire, Wilson, & Ciccone, 2010), and no study documented any negative effects of mail contact. Given these findings, we emphasize the need for interventions at each contextual level, especially when visits occur. We also highlight the positive aspects of remote forms of contact.

Our recommendations (see Table 3) regarding child contact reflect the ecological systems presented in our conceptual model. In keeping with our focus on children, we frame our recommendations from the “outside in,’ starting with the broad macrosystem. In making recommendations, we considered the quality of the research, which raises two important issues. First, we recognize that additional high-quality studies focusing on contact between incarcerated parents and their children are needed, which thus makes any recommendations tentative. Second, although such high-quality work is needed, the methodological rigor of the studies reviewed was unrelated to findings of positive or negative associations between contact and child or adult outcomes.

Table 3.

Recommendations Organized by Children’s Ecological Subsystems

| Subsystem | Recommendations regarding contact between children and incarcerated parents |

|---|---|

| Macrosystem | Implement Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (ASFA, 2000) timelines with incarcerated parents in a manner that is sensitive to their unique situations, and decrease racial disparities in implementation of ASFA |

| Improve coordination between the foster care and corrections/ criminal justice systems | |

| Implement the Second Chance Act of 2007: Community Safety Through Recidivism Prevention (2008) | |

| Improve corrections policies and programs to provide child-and family-friendly visitation and other forms of contact by

|

|

| Further examine the potential links between child visits and recidivism or inmate disciplinary infractions, paying particular attention to the context and quality of visits and parental gender |

|

Make efforts to decrease racial and educational disparities in

|

|

| Conduct a cost benefit analysis of different forms of parent child contact during parental incarceration | |

| Chronosystem | Improve sensitivity to children and parent child relationships during transitions, including

|

| Examine changes over time in incarcerated populations and how children are affected | |

| Mesosystem | Improve parent caregiver relationships and the parenting alliance |

| Improve communication between parents and caregivers | |

| Exosystem | Decrease parent and caregiver stress |

| Increase educational opportunities and interventions (and intervention research) that help incarcerated parents cope with feelings of loss and separation and learn healthy ways of interacting with children during visits and following reunification; decrease racial disparities in these opportunities |

|

| Provide resources and support to caregivers to facilitate positive parentchild contact, especially in communities of color that are most affected by parental incarceration |

|

| Microsystem | Note that children of different ages have different needs regarding parent child contact |

| Intervene to increase the likelihood that a visit or another form of contact will positively impact children’s attachment relationships and well-being by

|

|

| Recognize the complexity of the determination of the child’s best interest regarding contact with incarcerated parents if a dispute about contact arises among family members |

|

Increase opportunities for remote forms of contact such as

|

Improving the Macrosystem

The policies and laws that govern who goes to jail or prison represent one of the foremost factors that affect contact between children and their incarcerated parents. With more people in U.S. prisons than ever before (Sabol, West, & Cooper, 2009), a growing number of children experience separation from parents because of parental incarceration. The basis for this increase is the subject of considerable scholarly attention and includes multiple macrosystem factors, including changes in population demographics, sentencing policies, and increases in arrests for drug-related offenses (Mauer, 2002; Zhang, Maxwell, & Vaughn, 2009). In addition, ASFA may particularly affect families of the incarcerated, speeding the process of adoption for some children who are in foster care and who have incarcerated parents (Allard & Lu, 2006).

The increase in the number of affected children and families has recently led to an initiative that may improve the macrosystem for affected children and parents. The Second Chance Act of 2007: Community Safety through Recidivism Prevention (2008) authorizes assistance for offenders with the intention of reducing prison reentry. It specifically calls for the implementation of family-based treatment programs for incarcerated parents with minor children. As such initiatives take hold, there is promise for more innovative programming that may improve parent–child contact as well as provide better opportunities to systematically evaluate optimal conditions for contact.

Correctional policies regarding visitation likewise represent an important aspect of the child’s macrosystem that affects the quality of contact. Caregivers as well as incarcerated parents have reported wanting improved policies regarding visitation with family members (Arditti, 2003; Kazura, 2001), including provision of child-friendly settings that have age-appropriate games and toys for children. Our review suggests that several of the contradictory findings regarding the benefits, or lack thereof, of contact may be explained by differences in the hospitality of the visitation environment or the presence of an intervention to increase visitation quality.

There are several emerging programs that intentionally seek to provide enhanced child-centric contact opportunities; to help parents, caregivers, and children understand the context in which visitation occurs; and to prepare visitors and incarcerated parents for the emotional ramifications of visitation (e.g., Girl Scouts Beyond Bars; Block & Potthast, 1998). For example, the Linkages Program (see Grayson, 2007) gives incarcerated parents the opportunity to visit with their families face to face in a friendly environment at a monthly family night. Visitation would otherwise occur through a Plexiglas barrier. The incarcerated parents who participate in this program also attend weekly parenting education classes that address the needs of children. Extended visits (six hours) in a friendly, homelike cottage are also available to eligible incarcerated mothers and their children at some prisons (e.g., Harris, 2006), although the effects of such programs on children have not been systematically evaluated.

Concerns regarding the quality of prison and jail visitation also have important implications for corrections facilities and their policies. Textbooks focusing on correctional administration (e.g., Wilkinson & Unwin, 2008) and other publications (e.g., Laughlin, Arrigo, Blevins, & Coston, 2008) have emphasized the importance of visitation as a mechanism for reducing recidivism and improving institutional behavior. At least two states have enacted statutes that specifically require attention to family visitation within state prisons as a mechanism to improve prison safety and to reduce recidivism (Laughlin et al., 2008). However, visitation with children may not yield these intended benefits in the incarcerated individual’s adjustment (e.g., Bales & Mears, 2008; Casey-Acevedo et al., 2004) if the experience is marked by emotional distress. In corrections facilities with adverse visitation environments, the theorized positive link between parent–child contact and better adjustment on the part of the incarcerated parent may be undermined.

Because communities of color and impoverished communities have been strongly affected by increases in incarceration rates, interventions focusing on decreasing racial and educational disparities in arrest, sentencing, and incarceration rates are needed. These communities may also benefit from provision of resources to children of incarcerated parents that facilitate positive parent–child contact (e.g., providing transportation for visits, defraying the cost of phone calls, developing culturally relevant interventions).

Improving the Mesosystem

A positive relationship or parenting alliance between the child’s caregiver and the incarcerated parent is associated with more frequent parent–child contact (e.g., Loper et al., 2009), a finding suggesting the benefits of programs that directly assist caregivers in dealing with stress and communicating with incarcerated parents. Likewise, parenting programs for incarcerated individuals may benefit from deliberate inclusion of instructions regarding the best ways of communicating and coparenting with caregivers (Baker, McHale, Strozier, & Cecil, 2010; Loper & Tuerk, 2006).

Difficulties in forming strong coparenting alliances may relate, in part, to the different experiences of incarcerated parents, caregivers, and children regarding contact. Because of their isolation and disconnection from day-today experiences with children and families, as well as other factors, incarcerated parents may idealize their family relationships and contact experiences (e.g., Day et al., 2005). Whereas incarcerated parents may not understand the hard-ships incurred by caregivers and children around contact and other issues, caregivers may feel overwhelmed by their responsibilities and focus on problems. Caregivers may need time and space to reflect on the potential positive long-term benefits that may accrue from facilitating contact and a positive relationship between the incarcerated parent and the child, or at least to reflect on the situation from the child’s point of view. Psychologists and other mental health care providers who work with this population can help with the process of encouraging reflection, supporting families, and helping parents and caregivers deal with their own stress while staying attuned to children’s needs.

Improving the Exosystem