Abstract

Artemisia extracts have been used as remedies for a variety of maladies related to metabolic and gastrointestinal control. Because the vagal afferent-nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) synapse regulates the same homeostatic functions affected by Artemisia, it is possible that these extracts may have activity at the synaptic level in the NST. Therefore, we evaluated how extracts of three common medicinal Artemisia species, Artemisia santolinifolia (SANT), Artemisia scoparia (SCO), and Artemisia dracunculus L (PMI-5011), modulate the excitability of the glutamatergic vagal afferent-NST synapse. Our in vitro live cell calcium imaging data from prelabeled vagal afferent terminals show that SANT extract is a positive modulator of vagal afferent calcium levels, as the extract significantly increased the calcium signal relative to the time control. Neither SCO nor PMI-5011 extract altered the vagal calcium signals compared to the time control. Furthermore, whole cell voltage-clamp recordings from NST neurons corroborated the vagal terminal calcium data in that SANT extract also significantly increased miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) frequency in NST neurons. These data suggest that SANT extract could be a pharmacologically significant mediator of glutamatergic neurotransmission within the CNS.

Keywords: mEPSC, NST, botanical, calcium imaging, vagus nerve, presynaptic, electrophysiology

1. Introduction

Herbal supplements have been used for thousands of years as natural medicines and therapeutics. Over the last few decades, there has been increasing interest in the use of herbal remedies to treat diseases such as depression, diabetes, and gastrointestinal and stomach illnesses [4, 5, 9]. According to the 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), approximately 18 percent of American adults used a nonmineral or nonvitamin natural product in the previous year [5]. Worldwide, about 80% of the population relies on herbal or alternative healthcare [7].

Plants of the genus Artemisia have many uses, from foods and herbal remedies to insecticides [24]. The genus Artemisia is comprised of over 500 species and is found primarily in Europe, Asia, and North America [24, 27]. Extracts from Artemisia have been used as traditional remedies for many illnesses, including diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, hypertension, and pain [1, 7, 11, 18, 22-24, 26]. Little is known about how Artemisia extracts might work to affect metabolic and digestive regulatory mechanisms. However, these visceral functions rely on vago-vagal reflex autonomic control which is, in turn, mediated by vagal afferent inputs from the gut that synapse on visceral reflex control neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST) [6, 20]. These vagal synapses onto second-order NST neurons are typically glutamatergic [2, 13, 16]. Given that the NST is outside the blood-brain barrier, it is in a position to monitor circulating hormones, cytokines, and other agents, potentially including the bioactive constituents from Artemisia extracts [20].

We hypothesized that Artemisia extracts may modulate glutamatergic neurotransmission in the nucleus of the solitary tract. Therefore, we evaluated three medicinal Artemisia species, Artemisia santolinifolia (SANT), Artemisia scoparia (SCO), and Artemisia dracunculus L (PMI-5011), using calcium imaging of prelabeled vagal afferents to determine whether the extracts modulate vagal afferent calcium signals. We further evaluated whether SANT and SCO alter the frequency of vagal afferent glutamate release using whole cell voltage-clamp recordings of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs).

2. Methods

Long-Evans rats (body weight 130-250g; n=17; 41 brain slices) from the Pennington Biomedical Research Center breeding colony were used for these studies. Animals were housed in a room with a 12 hour light/dark cycle with constant temperature and humidity and had access to food and water ad libitum. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Pennington Biomedical Research Center and were performed according to the guidelines determined by the National Institutes of Health.

2.1. Vagal afferent labeling for calcium imaging

Vagal afferents were labeled as described previously [21]. A glass microinjection pipette pulled from 1.8mm OD starbore capillary tubing (~75-80μm tip diameter; Radnoti Glass Technologies) was filled with 20% CalciumGreen 1-dextran 10000 molecular weight conjugate (CG; Life Technologies) reconstituted in 1% Triton X-100 and distilled water. Rats were anesthetized using 2.5-5% isoflurane. Using aseptic technique, the right nodose ganglion was accessed through a ventral incision in the neck. The CG calcium reporter dye (~500nL) was injected into the nodose ganglion using the filled micropipette connected to a Picospritzer (General Valve). The cervical wound was closed, and the animal was housed in its home cage for 5-6 days to allow for anterograde transport of the dye to the vagal varicosities.

2.2. Brainstem slice preparation

The brainstem slices were obtained as previously described [25]. The animals were deeply anaesthetized using ethyl carbamate (urethane; 3g/kg; Sigma) and decapitated. The brainstem was glued to the stage of a vibrating microtome (Leica VT1200) and cut into 300μm coronal sections. The cutting chamber was filled with cold (4°C) carbogenated (95% O2/ 5% CO2) cutting solution containing (in mM) 92 N-methyl-D-glucamine, 30 NaHCO3, 25 glucose, 20 HEPES, 10 MgSO4-7H2O, 5 sodium ascorbate, 3 sodium pyruvate, 2.5 KCl, 2 thiourea, 1.25 NaH2PO4, and 0.5 CaCl2, titrated to pH 7.4 with HCl [28]. The brainstem sections were incubated at room temperature (22-24°C) for 1-6 hr in a carbogenated recording solution containing (in mM) 124 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.5 NaH2PO4, and 1 MgSO4-7H2O that was supplemented with 5 mM sodium ascorbate, 3 mM sodium pyruvate, and 2 mM thiourea and titrated to pH 7.4 with HCl [28].

2.3. Live cell calcium imaging

Live cell calcium imaging allows for the direct visualization of presynaptic calcium changes that are responsible for driving synaptic transmission between vagal afferents and NST neurons [20, 21]. We used this method to evaluate whether SANT, SCO, and PMI-5011 extracts exert effects on calcium signaling in vagal varicosities. Extracts of the dried SANT, SCO, and PMI-5011 herbs were prepared at Rutgers University as previously described [17]. The extracts were dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain 1000X stock solutions. All experimental solutions were prepared in the recording solution described in section 2.2 and contained a final concentration of 0.1% DMSO. Extract concentrations were chosen based on previously published papers [8, 19].

Brainstem slices were placed in the recording chamber of a Nikon F1 fixed stage upright microscope and were continuously perfused with carbogenated recording solution (33°C; 2.5 mL/min flow rate). A Prairie Technologies line-scanning laser confocal head equipped with a Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ camera performed time-lapse laser confocal calcium imaging. Images were collected at a rate of three frames per second, and the CG-labeled afferent terminals were visualized using a 488nm excitation/509nm long pass emission filter.

For each live cell imaging recording, the slices were perfused with control recording solution for 10 min. ATP (100μM) was bath applied (60s) to verify the viability of the vagal terminals as reflected by their ability to respond with calcium signals once their P2X3 ligand-gated cation channels were activated [12, 21]. The slices were then perfused with one of the following solutions for 10-20min:

Recording solution alone (“time control”)

1-50μg/mL SANT

25μg/mL SCO

25μg/mL PMI-5011

ATP (100μM; 60s) was then applied for a second time to each slice. Differences in response to the two exposures of ATP could be directly compared; thus, each varicosity could act as its own control.

The fluorescent signals were analyzed using Nikon Elements AR software as previously described [21] . Within each experimental slice, CG-labeled vagal varicosities were identified as fluorescent regions of interest (ROI). The relative changes in cytoplasmic calcium were calculated after the background fluorescence (as determined from a non-active portion of the field) was subtracted from both the at rest and peak fluorescence signals. The relative changes in cytoplasmic calcium were calculated as the percentage of change in CG fluorescence [(ΔF/F)%], where F is the baseline intensity of the fluorescence signal, and ΔF is the difference between the peak fluorescence intensity and baseline intensity. Only ROI with (ΔF/F)% values greater than 5% were included in the analyses. Response magnitudes to the second ATP exposure were directly compared to each ROI’s first ATP exposure; the first response was considered 100%. Thus, the second response was normalized as a percentage of the first.

Data were evaluated for statistical significance using a paired t-test or a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Data are reported as mean±S.E.M.; statistical significance was p<0.05.

2.4. Voltage-clamp recording from NST neurons

Vagal afferents were not prelabeled for these studies; however, all other preparations are as described in section 2.2. Brainstem slices were placed in the recording chamber of an upright microscope and were perfused with recording solution (33°C; 2.5 mL/min flow rate) supplemented with 0.5μM TTX and 10μM bicuculline. Recording electrodes were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass (Warner Instruments) using a Sutter Instruments P-97 micropipette puller (Rpip=3-5 MΩ). Pipettes were filled with (in mM) 120 Cs-methanesulfonate, 15 CsCl, 10 tetraethylammonim chloride, 10 HEPES, 8 NaCl, 3 Mg-ATP, 1.5 MgCl2, 0.3 Na-GTP, and 0.2 EGTA; pH 7.3 [10]. Whole cell voltage-clamp recordings of NST mEPSCs (VHOLD=−60 mV) were made using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices), filtered at 8 kHz, and digitized at 20 kHz using Axon pClamp10 software. The extract concentrations were determined by each extract’s limit of solubility when prepared in recording solution (SCO: 25μg/ml; SANT: 50μg/mL).

mEPSCs were analyzed as previously described using the Mini Analysis Program (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA) [25]. Only events with amplitudes greater than 3 times the root mean square of the noise and rise times more rapid than 10 ms were included in the analysis.

To determine if an Artemisia extract increased mEPSC frequency, we evaluated the distribution of mEPSC inter-event intervals for statistical significance using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov nonparametric analysis. The paired t-test was used to evaluate amplitudes and deactivation time constants before and after exposure to the Artemisia extracts. The deactivation time constants were calculated by fitting the following single exponential equation to selected scaled and averaged mEPSCs from each recording:

where τ is the deactivation time constant, and Amp is the current amplitude of the deactivation component. Significance was set at p<0.05, and data are reported as mean±S.E.M.

3. Results

3.1. Artemisia santolinifolia enhances vagal afferent terminal calcium signals

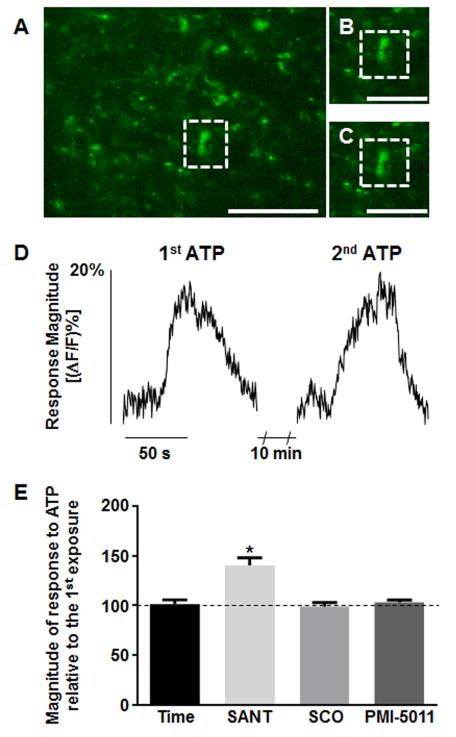

“Time control” applications of ATP involved exposing the slices twice to ATP (100μM; 60s) separated by 10 minute bath perfusions of recording solution alone (Fig. 1). On average, the first ATP application caused a relative increase in CG fluorescence [(ΔF/F)%] of 19.1±1.3% (n=59; Fig. 1), while the second ATP application resulted in a relative increase in CG fluorescence [(ΔF/F)%] of 17.9±1.1% (n=59; Fig. 1). There was no significant difference in CG fluorescence between the first and second applications of ATP in these experiments (p>0.05; paired t-test). Thus, slices could be exposed to repetitive applications of ATP and would produce comparable calcium flux responses [21].

Figure 1.

Repetitive applications of ATP (“time control”) produced comparable magnitudes of activation of prelabeled vagal varicosities. A, The complete field view of a brainstem slice is shown with a representative ROI outlined by a dotted box. B, Designated ROI is shown at rest. C, Same ROI at peak response to ATP stimulation. D, Plots of change in fluorescence over time for the above ROI shown in A-C following the first and second ATP stimulations. Scale bars: A=10μm; B and C=6μm. E, In a separate set of experiments, slices were perfused with recording solution plus SANT, SCO, or PMI-5011 between the two ATP applications. Only SANT extract significantly increased the ATP-evoked vagal calcium signal. *p<0.05; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

Other slices were exposed to the same experimental design of two activations with ATP, but this time the 10 min bath perfusion contained 25μg/ml concentrations of one of the three Artemisia extracts. The first response magnitude to ATP was considered “100%”, and the magnitude of the response following exposure to the extract was normalized to a percent change relative to the initial exposure. Only the SANT extract demonstrated a significant positive modulation of the vagal varicosities’ calcium levels; the other two extracts had no significant effect on the activity in these terminals (Fig. 1E; Table 1). Furthermore, SANT extract applied alone (25μg/ml) increased basal calcium fluorescence ((ΔF/F)%=36.1±3.0%; n=34).

Table 1.

SANT extract sensitizes vagal afferent calcium flux evoked by ATP

| Extract (25 μg/ml) |

% response to ATP (relative to initial response to ATP) |

Number of varicosities (ROI) |

|---|---|---|

| SANT | 135.4 ± 6.9 | 64 |

| SCO | 99.1 ± 3.7 | 45 |

| PMI-5011 | 103.6 ± 2.7 | 100 |

Response magnitudes to the second exposure to ATP were normalized as a percentage of the first ATP exposure for each ROI. Data are given as mean ± S.E.M.

Next, we evaluated whether the SANT extract modulated vagal afferent calcium influx in a concentration-dependent manner. In this subset of studies, each slice was bath exposed to one of three additional concentrations of SANT (1, 5, or 50μg/ml) during the 10 min interval between the two ATP stimulations. Relative to the “time control” responses to ATP, all concentrations of SANT except 1μg/ml significantly increased vagal terminal responses to ATP stimulation (p<0.05; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; Table 2).

Table 2.

SANT extract augments the responsiveness of the vagal afferent-NST synapse at concentrations as low as 5 μg/mL

| Concentration of SANT | % response to ATP (relative to initial response to ATP) |

Number of varicosities (ROI) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 μg/ml | 122.8 ± 13.0 | 12 |

| 5 μg/ml | 141.1 ± 8.3 | 85 |

| 25 μg/ml | 135.4 ± 6.9 | 64 |

| 50 μg/ml | 147.6 ± 3.8 | 146 |

The 5, 25, and 50 μg/ml SANT concentrations significantly increased the vagal terminal responses compared to ATP time control, while 1 μg/ml SANT did not have a significant effect on vagal afferent fluorescence. Furthermore, there was no difference in response between the 5, 25, and 50 μg/ml SANT concentrations. These data suggest that 5 μg/ml SANT will evoke the maximum effect on vagal afferent response. Response magnitudes to the second exposure to ATP were normalized as a percentage of the first ATP exposure for each ROI. Data are given as mean ± S.E.M. and were analyzed for statistical significance using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (p<0.05).

3.2. Artemisia santolinifolia increases the frequency of presynaptic glutamate release

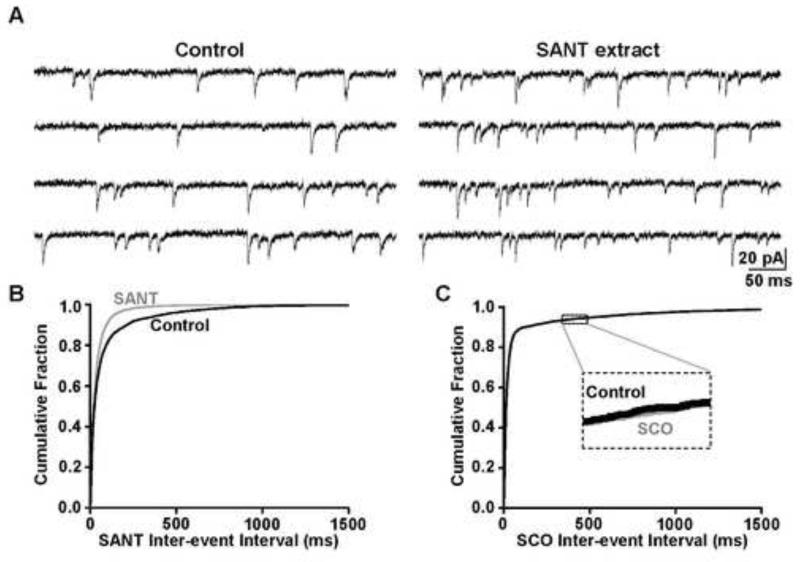

We recorded mEPSCs from NST neurons to determine if the extract-induced increase in vagal afferent calcium signals corresponded to a change in mEPSC frequency, amplitude, or deactivation time course. In this series of experiments we only investigated the SANT extract (which increased vagal calcium signals) and SCO extract (which had no effect on vagal calcium signals). All recordings were obtained at VHOLD=−60 mV; TTX and bicuculline were included in every solution.

Bath application of 50μg/mL SANT extract significantly increased the frequency of the NST mEPSCs, as the cumulative probability plot of inter-event intervals shows a significant leftward shift in the presence of SANT extract compared to the control (p<0.05; Kolmogorov-Smirnov; Fig. 2A,B). Indeed, the mEPSC frequency increased from 12.2±7.5 Hz in the control to 18.5±7.5 Hz in the presence SANT extract (n=4). The SANT effect was reversible, as the frequency returned to 12.0±5.7 Hz after a 10-15 min wash in recording solution alone, and bath application of the AMPA receptor antagonist DNQX fully inhibited the mEPSCs. SANT extract did not alter mEPSC amplitude (15.2±2.1 pA vs 14.6±1.4 pA; p>0.05; paired t-test), suggesting that the number of glutamate molecules released from the vagal terminals in each synaptic event were not altered by SANT extract. Deactivation time constant also was not significantly influenced by the SANT extract (2.8±0.2 ms vs 2.3±0.3 ms; p>0.05; paired t-test), indicating that the extract did not influence the time course of the synaptic currents in the postsynaptic NST neurons.

Figure 2.

A, We recorded mEPSCs from NST neurons to evaluate whether SANT and SCO extracts increased the frequency of glutamate release from vagal afferent terminals. Left panel: A representative control recording was obtained in the presence of bicuculline and TTX. Right panel: SANT extract in the perfusion media increased the frequency of events in the same recording. B, The distribution of inter-event intervals was shifted significantly to the left in the presence of SANT extract (gray) compared to control conditions (black) (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p<0.05). C, The SCO extract (gray) did not significantly shift the distribution of inter-event intervals compared to the control (black) (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, p>0.05).

Similar voltage-clamp recordings were obtained in the presence of the SCO extract. Unlike the SANT extract, SCO extract did not alter mEPSC frequency, as there was no significant difference in inter-event interval between the control and SCO conditions (p>0.05; Kolmogorov-Smirnov; Fig. 2C). Under control conditions (TTX and bicuculline), mEPSC frequency was 18.8±16.6 Hz, while mEPSC frequency was 19.3±17.4 Hz in the presence of 25μg/mL SCO extract (n=3). The mEPSC amplitudes (13.9±1.3 pA vs 13.7±2.0 pA; p>0.05; paired t-test) and deactivation time courses (2.9±0.2 ms vs 3.4±0.2 ms; p>0.05; paired t-test) also were not significantly different between the control and SCO recordings.

In summary, these calcium imaging data suggest that, of the three extracts examined, only the SANT extract changes the responsiveness of vagal varicosities. Our voltage-clamp electrophysiology corroborates these observations by demonstrating that SANT (but not SCO) extract increases the frequency of presynaptic glutamate release onto the NST neurons.

4. Discussion

In vitro live cell calcium imaging allowed us to directly visualize how the Artemisia extracts might influence the presynaptic calcium fluxes that are responsible for driving vagal-NST synaptic transmission [20, 21]. SANT augmented vagal afferent calcium levels in response to ATP stimulation and significantly increased the vagal calcium signal at concentrations as low as 5μg/mL compared to the time control; neither SCO nor PMI-5011 had any effect on vagal calcium levels. These data suggest that SANT extract includes one or more biologically active constituents not found in SCO or PMI-5011 that may control cytoplasmic calcium in vagal presynaptic terminals and, hence, neurotransmission.

Live cell imaging data showed that SANT increased vagal afferent calcium following pharmacological stimulation with ATP. However, even when applied alone and without further stimulation, SANT increased basal calcium levels of vagal varicosities. Resting calcium levels increased within 1-2 min following SANT application, similar in time frame to the onset of the increase in mEPSC frequency we observed in our electrophysiological recordings. These observations suggest that the increase in resting vagal calcium levels corresponds to an increase in the frequency of glutamate released from the vagal afferent terminals, as seen in our electrophysiological data showing significantly increased NST mEPSC frequency.

While the mechanism of action of SANT is unknown, previous studies indicate that St. John’s Wort extract and its constituent hyperforin increase neuronal cytosolic calcium and sodium levels and enhance mEPSC frequency in a manner similar to what we observe with SANT by activating transient receptor potential (TRPC6) receptors [14, 15, 25]. It is possible that SANT also activates TRP channels, and the calcium signal may be enhanced through the release of endoplasmic reticulum calcium via calcium-induced calcium release [3].

In conclusion, our study indicates that SANT is capable of positively modulating excitatory synaptic neurotransmission. Regulation of this vagal afferent-NST synapse by SANT may have significant effects on physiological processes under autonomic control; thus, sensitization of this synapse may suppress gastric motility, lower blood glucose, and enhance early satiety [6, 20]. Future studies need to be conducted to identify the biologically active constituents of SANT and what the mechanisms of action are for these agents.

Highlights.

We evaluated how three Artemisia species modulate the vagal afferent-NST synapse.

A. santolinifolia increases calcium levels in prelabeled vagal afferent terminals.

Neither A. scoparia nor A. dracunculus L extract altered the vagal calcium signals.

A. santolinifolia, but not A. scoparia, increased mEPSC frequency in NST neurons.

A. santolinifolia may be a significant mediator of glutamatergic neurotransmission.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by NIH T32-AT004094 (KMV), NS60664 (RCR), and the Botanical Research Center grant P50AT002776-01 (DMR).

Abbreviations

- CG

CalciumGreen 1-dextran

- DNQX

7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione

- mEPSC

miniature excitatory postsynaptic current

- NST

nucleus of the solitary tract

- PMI-5011

Artemisia dracunculus L

- ROI

region of interest

- SANT

Artemisia santolinifolia

- SCO

Artemisia scoparia

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Author Contributions. KMV, GEH, and RCR designed the study, conducted the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. DMR purified the extracts.

References

- [1].Aglarova AM, Zilfikarov IN, Severtseva OV. Biological characteristics and useful properties of tarragon (Artemisia dracunculus L.) Pharm. Chem. J. 2008;42:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aylwin ML, Horowitz JM, Bonham AC. Non-NMDA and NMDA receptors in the synaptic pathway between area postrema and nucleus tractus solitarius. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circul. Physiol. 1998;275:H1236–H1246. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bardo S, Cavazzini MG, Emptage N. The role of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store in the plasticity of central neurons. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barnes J, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD. St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum L.): a review of its chemistry, pharmacology and clinical properties. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2001;53:583–600. doi: 10.1211/0022357011775910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Barnes P, Bloom B, Nahin R. CDC National Health Statistics Report #12. 2008. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults and Children: United States, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Blessing W. The lower brainstem and body homeostasis. Oxford UP, New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bora KS, Sharma A. The Genus Artemisia: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2011;49:101–109. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2010.497815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boudreau A, Cheng DM, Ruiz C, Ribnicky D, Allain L, Brassieur CR, Turnipseed DP, Cefalu WT, Floyd ZE. Screening native botanicals for bioactivity: An interdisciplinary approach. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2014;30:S11–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Eddouks M, Magharani M, Lemhadri A, Ouahidi ML, Jouad H. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used for the treatment of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiac disease in the south-east region of Morocco (Tafilalet) Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2002;82:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Chan CS, Surmeier DJ. Robust Pacemaking in Substantia Nigra Dopaminergic Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11011–11019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2519-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jakupovic J, Tan RX, Bohlmann F, Jia ZJ, Huneck S. Seco-sesquiterpene and nor-sequiterpene lactones with a new carbon skeleton from Artemisia santolinifolia. Phytochemistry. 1991;30:1941–1946. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jin YH, Bailey TW, Li BY, Schild JH, Andresen MC. Purinergic and vanilloid receptor activation releases glutamate from separate cranial afferent terminals in nucleus tractus solitarius. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4709–4717. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0753-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Leone C, Gordon FJ. Is L-glutamate a neurotransmitter of baroreceptor information in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1989;250:953–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Leuner K, Kazanski V, Mueller M, Essin K, Henke B, Gollasch M, Harteneck C, Mueller WE. Hyperforin - a key constituent of St. John’s wort specifically activates TRPC6 channels. Faseb Journal. 2007;21:4101–4111. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8110com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Leuner K, Li W, Amaral MD, Rudolph S, Calfa G, Schuwald AM, Harteneck C, Inoue T, Pozzo-Miller L. Hyperforin modulates dendritic spine morphology in hippocampal pyramidal neurons by activating Ca2+-permeable TRPC6 channels. Hippocampus. 2013;23:40–52. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ohta H, Talman WT. Both NMDA and Non-NMDA receptors in the NTS participate in teh baroreceptor reflex in rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 1994;267:R1065–R1070. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.4.R1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, O’Neal J, Wnorowski G, Malek DE, Jager R, Raskin I. Toxicological evaluation of the ethanolic extract of Artemisia dracunculus L. for use as a dietary supplement and in functional foods. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004;42:585–598. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ribnicky DM, Poulev A, Watford M, Cefalu WT, Raskin I. Antihyperglycemic activity of Tarralin (TM), an ethanolic extract of Artemisia dracunculus L. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Richard AJ, Burris TP, Sanchez-Infantes D, Wang Y, Ribnicky DM, Stephens JM. Artemisia extracts activate PPAR gamma, promote adipogenesis, and enhance insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue of obese Mice. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2014;30:S31–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Rogers RC, Hermann GE. Brainstem Control of Gastric Function. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Academic Press; 2012. pp. 861–892. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rogers RC, Nasse JS, Hermann GE. Live-cell imaging methods for the study of vagal afferents within the nucleus of the solitary tract. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2006;150:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Subramoniam A, Pushpangadan P, Rajasekharan S, Evans DA, Latha PG, Valsaraj R. Effects of Artemisia pallens Wall on blood glucose levels in normal and alloxan-induced diabetic rats. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1996;50:13–17. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Swanstonflatt SK, Flatt PR, Day C, Bailey CJ. Traditional dietary adjucts for the treatment of diabetes-mellitus. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 1991;50:641–651. doi: 10.1079/pns19910077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tan RX, Zheng WF, Tang HQ. Biologically active substances from the genus Artemisia. Planta Medica. 1998;64:295–302. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vance KM, Ribnicky DM, Hermann GE, Rogers RC. St. John’s Wort enhances the synaptic activity of the nucleus of the solitary tract. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 2014;30:S37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang ZQ, Zhang XH, Yu YM, Tipton RC, Raskin I, Ribnicky D, Johnson W, Cefalu WT. Artemisia scoparia extract attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in diet-induced obesity mice by enhancing hepatic insulin and AMPK signaling independently of FGF21 pathway. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental. 2013;62:1239–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Watson LE, Bates PL, Evans TM, Unwin MM, Estes JR. Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera. Bmc Evolutionary Biology. 2002;2 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zhao SL, Ting JT, Atallah HE, Qiu L, Tan J, Gloss B, Augustine GJ, Deisseroth K, Luo MM, Graybiel AM, Feng GP. Cell type-specific channelrhodopsin-2 transgenic mice for optogenetic dissection of neural circuitry function. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:745–U791. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]