Abstract

Background:

Fat grafting is now widely used in plastic surgery. Long-term graft retention can be unpredictable. Fat grafts must obtain oxygen via diffusion until neovascularization occurs, so oxygen delivery may be the overarching variable in graft retention.

Methods:

We studied the peer-reviewed literature to determine which aspects of a fat graft and the microenvironment surrounding a fat graft affect oxygen delivery and created 3 models relating distinct variables to oxygen delivery and graft retention.

Results:

Our models confirm that thin microribbons of fat maximize oxygen transport when injected into a large, compliant, well-vascularized recipient site. The “Microribbon Model” predicts that, in a typical human, fat injections larger than 0.16 cm in radius will have a region of central necrosis. Our “Fluid Accommodation Model” predicts that once grafted tissues approach a critical interstitial fluid pressure of 9 mm Hg, any additional fluid will drastically increase interstitial fluid pressure and reduce capillary perfusion and oxygen delivery. Our “External Volume Expansion Effect Model” predicts the effect of vascular changes induced by preoperative external volume expansion that allow for greater volumes of fat to be successfully grafted.

Conclusions:

These models confirm that initial fat grafting survival is limited by oxygen diffusion. Preoperative expansion increases oxygen diffusion capacity allowing for additional graft retention. These models provide a scientific framework for testing the current fat grafting theories.

Autologous fat grafting is increasingly used for breast augmentation and reconstruction.1–5 Fat grafts are easily available, biocompatible, cause low donor-site morbidity, and give grafted sites a natural appearance. However, fat grafting is generally considered an unpredictable procedure,6 with long-term retention commonly varying between 10% and 80%.7–14 Much work has been done to optimize this procedure; however, the clinical practice has advanced faster than the supporting science. Fat grafting can be considered in 4 phases: harvesting, processing, reinjecting, and managing the recipient site.15 To determine the optimal surgical methods for harvesting, processing, and reinjecting, Gir et al6 completed an extensive literature review. Their results show the variability of current surgical techniques with current literature only supporting general principles and not any specific technique. Furthermore, no experimental or theoretical studies have analyzed how the different surgical methods alter the microenvironment surrounding the graft or how the microenvironment affects graft retention.

In this context, we define a model as a conceptual and mathematical representation of a phenomenon that has occurred in the past in an attempt to predict how it will occur in the future as specific variables change. Modeling has been critical for many advances in plastic surgery. Our group has modeled both skin expansion and the mechanical forces involved in vacuum-assisted closure devices.16,17 These models have helped enhance our understanding of the biological effects and medical uses of mechanical forces. Modeling provides the theoretical framework for testing theories. This study aims to identify the role of the recipient site in fat grafting and create a model to serve as a scientific basis to analyze the variables related to the recipient site and graft retention.

Grafted fat initially lacks vascular support and must receive oxygen and nutrients by diffusion from nearby capillaries until neovascularization occurs.18 Oxygen seems to be the critical molecule required for cell survival. Low oxygen partial pressures in the center of the graft can lead to cell necrosis. Attempts to improve graft retention have largely been based on the “cell survival theory,” which states that long-term graft volume consists primarily of grafted adipocytes that have survived the entire procedure.15 This theory has generally been accepted18,19 and has directed most efforts to maintaining adipocytes viability through improved harvesting, processing, and reinjecting techniques.19–21 Studies supporting the cell survival theory claim that the “viable zone” (40% adipocyte survival) reaches as far down as 0.2 cm from the periphery of the grafted tissue.22 These conclusions are based mostly on morphological observations with H&E staining. However, judging adipocyte health by shape or nuclear appearance can be misleading, and histologic sections are too thin to show most nuclei of healthy adipocytes.23 Moreover, the “cell survival theory” may fail to get to the complex phenomena occurring in fat grafting. Fat grafts are not pure aggregates of adipocytes, but a mixture of adipocytes, preadipocytes, endothelial cells, pericytes, stem cells, fibroblasts, inflammatory cells, and matrix.

Using immunostain for perilipin, a method for determining adipocyte viability,24 Eto et al23 in the Yoshimura Lab tested the cell survival theory and concluded that a dynamic remodeling of grafted adipose tissue (AT) occurs. In hypoxic cell cultures, they demonstrated that adipocytes cannot survive more than 1 day of severe ischemia-mimicking conditions (1% O2 with no serum), whereas adipose-derived stromal cells (ASCs) remained viable for up to 72 hours. In a second experiment, the inguinal fat pad of a mouse was grafted to the scalp. Only the peripheral area (surviving zone; <0.03 cm from the edge) of the graft had a high survival rate of both adipocytes and ASCs. In a deeper (regenerating) zone, most adipocytes did not survive more than 1 day, but ASCs survived and eventually provided new adipocytes. By day 3, the number of proliferating cells increased, and by day 7, they found an increased thickness of the zone with viable adipocytes. At the center of the graft, no AT survived, and macrophages removed the dead cells25; this was named the “necrotic zone.”

Recent studies support this “host replacement theory.” Rigamonti et al26 suggest that 4.8% of preadipocytes are replicating at any time, and 1–5% of adipocytes are replaced each day. When mouse AT oxygenation reaches less than 65% of baseline, adipocytes undergo apoptosis in 24 hours; however, ASCs can survive for multiple days in severe hypoxia.27 Hypoxia is known to enhance ASC proliferation.28,29 Injured adipocytes release fibroblast growth factor-2, which stimulates ASC proliferation and hepatocyte growth factor, contributing to the regeneration of AT.30 The retention of grafted fat largely depends on the distance metabolites must travel to reach the center of the graft and on the depths of the surviving and regenerating zones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We searched Pubmed for original articles with the term “fat grafting” in the title or abstract to determine which aspects of the microenvironment surrounding fat grafts affect retention. We modeled the relationship between oxygen consumption by metabolizing fat tissue and oxygen delivery via diffusion for grafted fat cylinders of varying radii. We called this the “Microribbon Model.”

In a steady state, oxygen delivery matches oxygen consumption, and oxygen must diffuse off erythrocytes, through the capillary walls, through the extracellular space, and into the grafted cells. To optimize the potential for oxygen delivery, the vascular perfusion must be functioning properly, and several articles propose that an increased interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) during fat grafting might restrict perfusion. To determine the physiological plausibility of this hypothesis, we modeled the relationship between fluid accumulation, IFP, and perfusion. We called this the “Fluid Accommodation Model.”

To study how the information from the first 2 models can be used to optimize the fat grafting procedure, we explored which existing fat grafting procedures were attempting to optimize the variables in our models. Although several articles emphasized a biological approach with cytokines and stem cells, only external volume expansion (EVE) emphasized enhancing oxygen delivery. Therefore, we modeled how EVE could prepare the recipient site to allow the critical variables in the first 2 models to be optimized during fat grafting. We called this the “EVE Effect Model.” The information from these models comes from our calculations derived from established equations, relationships, and constants.

RESULTS

The literature to date concludes that oxygen delivery seems to be the most crucial molecule for fat graft survival. The thickness of the exterior rim of viable cells in multicell spheroids increases linearly with the theoretical oxygen diffusion distance.31 Oxygen diffusion is the limiting variable in determining cell survival in spheroids.32 Therefore, it seems that the core principle of fat graft survival is that oxygen concentration at any point in a graft is a function of the oxygen concentration of the surrounding capillaries, the diffusion rate of oxygen to reach that point in the tissue, the distance from the oxygen source, and the metabolic rate. In other words, at every point within a fat graft, there is a race between the rate at which oxygen is needed by the cells and the rate at which oxygen can be delivered by the capillaries and diffused through the AT.

According to standard principles in physiology, the metabolic rate of a given section of AT is directly proportional to its volume (V). However, the diffusion rate of any substance is directly proportional to the surface area (SA) over which diffusion takes place, and the SA:V ratio of any interior section of a cylinder is (2/radius). Therefore, as the radius of a cylindrical injection of AT increases, the SA:V ratio decreases, and oxygen’s diffusion rate cannot meet the tissue’s metabolic needs. In addition, diffusion is related to the square of the distance between the oxygen source and where it is consumed. When the distance is increased by a factor of 2, the delivery of oxygen is decreased by a factor of 4.

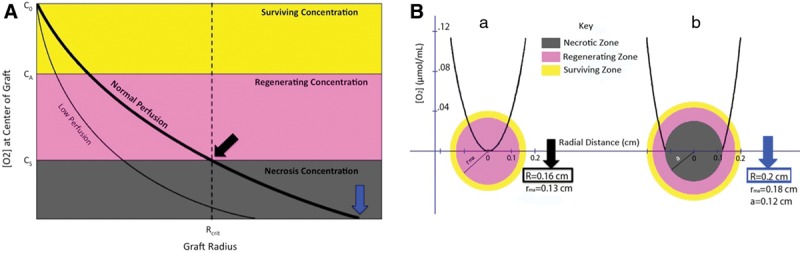

Using diffusion and metabolism equations and biological and physical constants,31–37 we modeled the theoretical borders between the surviving, regenerating, and necrotic zones for fat grafts of different radii (Appendix 1) (Fig. 1). According to the Microribbon Model in standard human conditions, the largest fat microribbon with no necrotic zone would have a radius of 0.16 cm. Such a graft would have a surviving zone of 0.03 cm and a regenerating zone of 0.13 cm. As graft radius increases beyond this point, the necrotic zone grows rapidly.

Fig. 1.

A, Theoretical representation of oxygen concentration at the center of a fat graft as a function of its radius. There are 3 zones of oxygen concentration. The surviving zone has C > CA. The regenerating zone has CA > C > CS. The necrotic zone has C < CS.20 B, Cross-sectional views of cylindrical fat injections, showing [O2] as a function of radial distance. a, Cylindrical injection with R = Rcrit. Adipocytes only survive in the outer 0.03 cm. ASCs survive throughout. b, Cylindrical injection with R > Rcrit. Adipocytes only survive in the outer 0.02 cm. ASCs only survive in the outer 0.08 cm. No cells survive in the inner 0.12 cm.

This Microribbon Model correlates well with experimental data. When multicell spheroids were cultured in excess medium, the spheroids ceased to expand at a radius of 0.15 cm.38 Carpaneda and Ribeiro22 suggest that, in humans, only the region 0.15 cm from the edge of a fat graft retains a significant percent of its volume. Current successful method descriptions suggest a 0.13-cm limit for the radius of reinjected fat.39,40 Multiple studies report negative correlation between fat graft particle width and retention percentage.8,15,25,41 Long-term fat graft retention requires small volumes of fat to be diffusely distributed into a well-vascularized recipient site through well-separated tunnels.1,4,8,41–43 If the microinjections are not diffusely distributed in the recipient site, they will coalesce, forming particles too wide to survive.25,39,40

Fat graft survival is also largely dependent on the vasculature’s ability to delivery oxygen blood through the capillaries surrounding the graft.39,40,44,45 Several surgeons have suggested that injecting too much fat into a small recipient site can increase IFP enough to constrict capillaries, inducing ischemia in the grafted tissues.5,15,39,40,45 Guyton46 demonstrated that, for up to a certain volume, interstitial fluid can accumulate in a tissue without significant IFP increase, but beyond that range, any additional fluid causes drastic IFP increases, quickly reaching levels associated with compartment syndrome.47 Milosevic et al48 also demonstrated that capillary perfusion decreases with increasing IFP. Therefore, it is recognized that fluid accumulation can lead to increased IFP and that increased IFP can lead to decreased capillary perfusion.

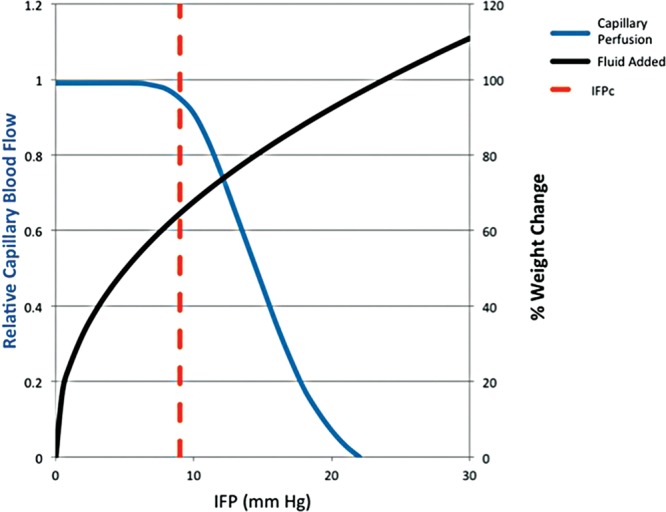

Using these relationships, we modeled the change in relative capillary perfusion as a function of IFP and interstitial fluid accumulation to determine if increased IFP during fat graft is enough to limit capillary perfusion and oxygen delivery (Fig. 2). According to this Fluid Accommodation Model, a given tissue compartment can accommodate about 60% of its weight in interstitial fluid before reaching a critical IFP (IFPC) of 9 mm Hg, beyond which, any additional fluid causes a drastic IFP increase and capillary perfusion decrease. It is important to recognize that this 60% accommodation is a generalized estimation, which will change with differences in the compliance of tissues; therefore, the IFP could be monitored intraoperatively if excess fat injections could be a possibility.39,40 This IFPC closely correlates with recent suggestions of IFP-based fat grafting stop points of 9–10 mm Hg.39,40,49,50 Increased IFP may also inhibit retention of grafted cells by mechanical compression, which induces apoptosis and regulates cytokine release.51 Therefore, interstitial volume, compliance, and vascularity determine how many microribbons of fat can be dispersed before increasing IFP enough to significantly reduce perfusion and cell survival.

Fig. 2.

IFP as a function of percent change in leg weight by saline injection in isolated dog hindleg (black).46 Mathematical model of relative capillary blood flow as a function of IFP (blue).48 IFPC = IFP at which perfusion becomes compromised quickly; fat grafting should be stopped at this point.

Mechanical forces can induce angiogenesis, adipogenesis, and increased subcutaneous tissue thickness and compliance.16,39,40,45,52–58 Our group previously studied the mechanism behind EVE’s effects54 and found that the macroscopic swelling is likely due to deformation of the extracellular matrix, which induces tension on the cells anchored to extracellular matrix fibers. This micromechanical strain is transferred to the cytoskeleton,59 where it acts as a gate-control signal to induce proliferation.60 EVE-induced ischemia activates the hypoxia inducible factor -1α/vascular endothelial growth factor pathway to induce vascular remodeling, angiogenesis, and cell proliferation.55 Adipogenesis can be induced by lymphedema or water-rich empty proteinaceous matrices.61–69 Inflammation promotes these processes.70

Khouri et al56 developed a suction-based EVE bra (BRAVA) that noninvasively induces long-term breast growth in humans.71 It uses cyclical forces, which have a greater effect than continuous forces.16 Daily BRAVA-use induces temporary edema and angiogenesis and sustained increases in subcutaneous tissue thickness and compliance.39,45,56 Once fat grafting to the breast was more accepted and understood, BRAVA was proposed for application in preparation for fat grafting. Pre-expansion and resultant augmentation had a strong linear correlation (R2 = 0.87), and pre-expansion allowed significantly more AT to be grafted and retained than what was reported in a meta-analysis of 6 other published reports on fat graft breast augmentation without pre-expansion (P < 0.00001).45 Preoperative expansion also has several clinical applications in breast augmentation and reconstruction (Khouri et al, unpublished data, 2014).5,39,40,45,49,72,73

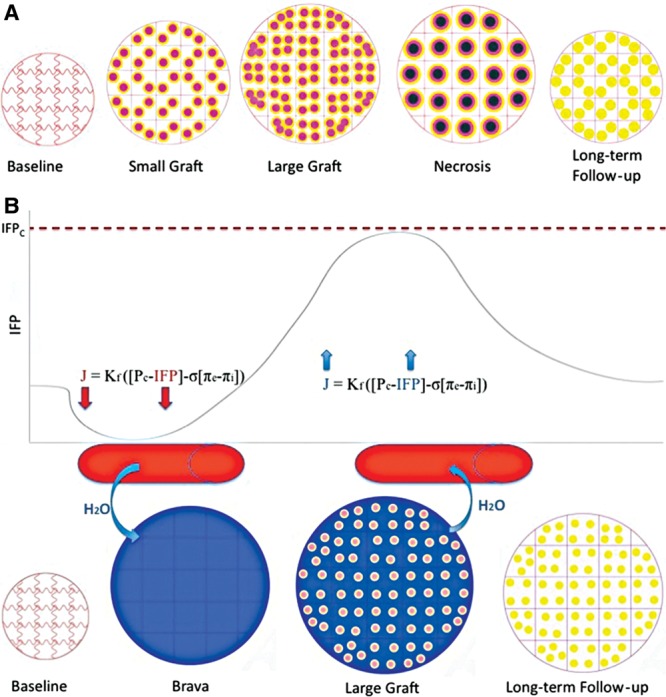

To understand the effectiveness of EVE devices for fat grafting, we must consider the ratio of grafted fat to recipient site volume. If the original recipient site is 100 mL and noncompliant, and 30 mL of AT are to be grafted, there is no need for pre-expansion because, with a 30% increase, the AT can be diffusely microinjected. If the original recipient site is 100 mL, and the volume of AT to be grafted is 90 mL, this 90% increase cannot be done without overcrowding, which would cause coalescence, increased IFP, reduced perfusion and oxygen delivery, thinner surviving and regenerating zones, and significant volume loss (Fig. 3A). However, our EVE Effect Model predicts that a tight 100-mL recipient site can be transformed into a compliant 300-mL site and, according to the Starling equation, cause edema influx. Because the fat microribbons can be diffusely dispersed into the pre-expanded tissue, less coalescence occurs and more AT can be grafted before reaching IFPC. As IFP increases, the Starling equation dictates that interstitial fluid is reabsorbed, allowing IFP to quickly return to baseline levels (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

A, Fat-grafting process without BRAVA. Overcrowding causes coalescence and high IFP, which cause insufficient oxygen delivery, leading to central necrosis, volume loss, and microcalcification. B, Relative IFP throughout fat-grafting process with EVE. Long-term EVE expands tissues and causes an influx of edema, according to the Starling equation. Because the tissue is pre-expanded, as fat is injected, less coalescence occurs and more fat can be grafted before IFP reaches IFPC. As pressure increases, edema quickly leaves the tissues, allowing pressure to return to baseline levels.

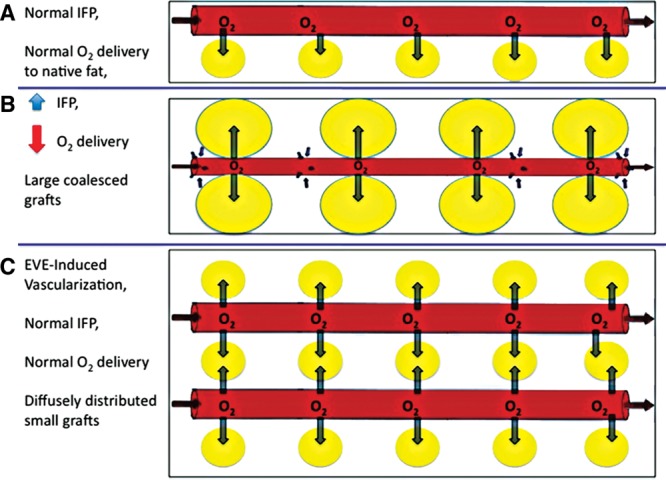

Our EVE Effect Model also predicts that the preoperative cyclical negative pressure treatment increases the host vascular density and diameter, increasing total oxygenated blood delivery, decreasing the mean distance each oxygen molecule must diffuse to reach the center of a grafted microribbon, and accelerating graft revascularization: a major determinant of volume retention (Fig. 4).25,42,73–76

Fig. 4.

A, At baseline, IFP is at basal state, so capillary radius is at basal state, and native fat receives sufficient oxygen delivery. B, When large volumes of fat are grafted without pre-expansion, fat particles coalesce and IFP increases, causing decreased capillary radius and oxygen delivery to grafted fat. C, When the same volume of fat is grafted with pre-expansion, fat particles remain diffusely distributed and IFP remains below IFPC, so capillary radius remains uncompromised, and the grafted fat receives sufficient oxygen delivery.

DISCUSSION

We have presented 3 models to predict how recipient site vascularity, volume, and compliance determine fat graft retention by regulating oxygen delivery via perfusion and diffusion. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to mathematically model the essential variables relating to oxygen delivery and graft retention. The information from these models comes from our calculations derived from established equations, relationships, and constants. Our Microribbon Model suggests that any fat injection with a radius greater than 0.16 cm in standard human conditions will have a zone of central necrosis. Our Fluid Accommodation Model suggests that interstitial fluid injections that cause IFP to increase past IFPC will restrict perfusion. Our EVE Effect Model explains how the information from the first 2 models can be used to optimize the fat grafting procedure. It predicts that preoperative EVE increases recipient site vascularity, volume, and compliance, allowing more AT to be successfully grafted. For grafting small volumes of fat into large, compliant, highly vascularized recipient sites, the recipient bed will likely accept the graft even if the surgeon does not specifically consider each of the variables in these models. However, for grafting large volumes of fat into small, restricted, poorly vascularized recipient sites for procedures such as total breast reconstruction, or irradiated tissues, surgeons must optimize each of the variables related to graft retention. None of these models can predict fat graft retention on their own, but taken together, they enhance our understanding of the biological events occurring during fat grafting and allow us harness this knowledge to enhance surgical outcomes.

Modeling provides the theoretical framework for testing theories, so these models require experimental data to be further accepted. To test the Microribbon Model, experiments similar to the ones performed by Eto et al23 would have to be reproduced, but pO2 would have to be measured at various depths within grafts or cylindrical cell cultures of various radii. To test the Fluid Accommodation Model, studies would have to measure IFP, perfusion, and pO2 as fluid is injected into living tissue. To test the EVE Effect Model, a complex set of experiments would be required. More importantly, to truly test the effects of EVE in fat grafting, a large prospective randomized controlled trial should be performed. It is hoped that these studies will lead to long-term prospective studies in humans.

Conclusion

Our models predict the following: that fat injections larger than 0.16 cm in radius will have an area of central necrosis; that, in fat grafting, IFPs greater than 9 mmHg will cause decreased capillary perfusion; and that EVE can enhance tissue volume, vascularity, and compliance, allowing more AT to be successfully grafted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kazi Zein Hassan for assisting with figure production and Chenyu Huang, MD, PhD, for assisting with editing the text.

Appendix 1

The following formulas model O2 diffusion into a metabolizing cylinder of tissue33:

1. C = C0 − (M/4D)[(R2 − r2) − a2 ln(R2/r2)]

2. a2 = [1 + ln(R2/a2)] = R2 − (Rcrit)2

3. Rcrit = sqrt(4DC0/M)

C = [O2] at a radial distance (r) cm from the center of a cylinder (μmol/mL)

C0 = [O2] at the surface of a cylinder of radius R cm (μmol/mL)

CS = min [O2] at which ASCs can survive (μmol/mL)

CA = min [O2] at which adipocytes can survive (μmol/mL)

M = metabolic rate [μmol/(mL × min)]

D = O2 diffusion coefficient (cm2/min)

Rcrit = largest radius (R) such that ASCs survive throughout the graft (cm)

a = max radial distance (r) at which [O2] = 0 when R > Rcrit (cm)

rma = min distance from center (r) at which adipocytes can survive (cm)

Using these equations and established constants,23,31–34 we calculated that Rcrit = 0.16 cm.

When R = Rcrit, rma = 0.13 cm.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. The Article Processing Charge was paid for by the Tissue Engineering and Wound Healing Lab, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Mass.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coleman SR. Structural fat grafts: the ideal filler? Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanchwala SK, Holloway L, Bucky LP. Reliable soft tissue augmentation: a clinical comparison of injectable soft-tissue fillers for facial-volume augmentation. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:30–35. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000168292.69753.73. discussion 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bucky LP, Kanchwala SK. The role of autologous fat and alternative fillers in the aging face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(6 Suppl):89S–97S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000248866.57638.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khouri R, Del Vecchio D. Breast reconstruction and augmentation using pre-expansion and autologous fat transplantation. Clin Plast Surg. 2009;36:269–280, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khouri RK, Smit JM, Cardoso E, et al. Percutaneous aponeurotomy and lipofilling: a regenerative alternative to flap reconstruction? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1280–1290. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4c3a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gir P, Brown SA, Oni G, et al. Fat grafting: evidence-based review on autologous fat harvesting, processing, reinjection, and storage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:249–258. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b4d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ersek RA. Transplantation of purified autologous fat: a 3-year follow-up is disappointing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niechajev I, Sevćuk O. Long-term results of fat transplantation: clinical and histologic studies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:496–506. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199409000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubin A, Hoefflin SM. Fat purification: survival of the fittest. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1463–1464. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200204010-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf GA, Gallego S, Patrón AS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of gluteal fat grafts. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2006;30:460–468. doi: 10.1007/s00266-005-0202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zocchi ML, Zuliani F. Bicompartmental breast lipostructuring. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:313–328. doi: 10.1007/s00266-007-9089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delay E, Garson S, Tousson G, et al. Fat injection to the breast: technique, results, and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29:360–376. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S, Kim B, Shin Y. Correction of superior sulcus deformity with orbital fat anatomic repositioning and fat graft applied to retro-orbicularis oculi fat for Asian eyelids. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35:162–170. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9574-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi M, Small K, Levovitz C, et al. The volumetric analysis of fat graft survival in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:185–191. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182789b13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Vecchio D, Rohrich RJ. A classification of clinical fat grafting: different problems, different solutions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:511–522. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dbf8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin MS, Ogawa R, Lancerotto L, et al. In vivo acceleration of skin growth using a servo-controlled stretching device. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:397–405. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saxena V, Hwang CW, Huang S, et al. Vacuum-assisted closure: microdeformations of wounds and cell proliferation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1086–1096. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000135330.51408.97. discussion 1097–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billings E, Jr, May JW., Jr Historical review and present status of free fat graft autotransplantation in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:368–381. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198902000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rohrich RJ, Sorokin ES, Brown SA. In search of improved fat transfer viability: a quantitative analysis of the role of centrifugation and harvest site. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:391–395. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000097293.56504.00. discussion 396–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortese A, Savastano G, Felicetta L. Free fat transplantation for facial tissue augmentation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:164–169; discussion 169–170. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(00)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piasecki JH, Gutowski KA, Lahvis GP, et al. An experimental model for improving fat graft viability and purity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:1571–1583. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000256062.74324.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpaneda CA, Ribeiro MT. Study of the histologic alterations and viability of the adipose graft in humans. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1993;17:43–47. doi: 10.1007/BF00455048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eto H, Kato H, Suga H, et al. The fate of adipocytes after nonvascularized fat grafting: evidence of early death and replacement of adipocytes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1081–1092. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824a2b19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tansey JT, Sztalryd C, Gruia-Gray J, et al. Perilipin ablation results in a lean mouse with aberrant adipocyte lipolysis, enhanced leptin production, and resistance to diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6494–6499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101042998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smahel J. Experimental implantation of adipose tissue fragments. Br J Plast Surg. 1989;42:207–211. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(89)90205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rigamonti A, Brennand K, Lau F, et al. Rapid cellular turnover in adipose tissue. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suga H, Eto H, Aoi N, et al. Adipose tissue remodeling under ischemia: death of adipocytes and activation of stem/progenitor cells. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1911–1923. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f4468b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee EY, Xia Y, Kim WS, et al. Hypoxia-enhanced wound-healing function of adipose-derived stem cells: increase in stem cell proliferation and up-regulation of VEGF and bFGF. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weijers EM, Van Den Broek LJ, Waaijman T, et al. The influence of hypoxia and fibrinogen variants on the expansion and differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2675–2685. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suga H, Eto H, Shigeura T, et al. IFATS collection: fibroblast growth factor-2-induced hepatocyte growth factor secretion by adipose-derived stromal cells inhibits postinjury fibrogenesis through a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2009;27:238–249. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franko AJ, Sutherland RM. Oxygen diffusion distance and development of necrosis in multicell spheroids. Radiat Res. 1979;79:439–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkatasubramanian R, Henson MA, Forbes NS. Incorporating energy metabolism into a growth model of multicellular tumor spheroids. J Theor Biol. 2006;242:440–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomlinson RH, Gray LH. The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1955;9:539–549. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1955.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chow DC, Wenning LA, Miller WM, et al. Modeling pO(2) distributions in the bone marrow hematopoietic compartment. I. Krogh’s model. Biophys J. 2001;81:675–684. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75732-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Croll TI, Gentz S, Mueller K. Modelling oxygen diffusion and cell growth in a porous, vascularising scaffold for soft tissue engineering applications. Chem Eng Sci. 2005;60:4924–4934. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goossens GH, Bizzarri A, Venteclef N, et al. Increased adipose tissue oxygen tension in obese compared with lean men is accompanied by insulin resistance, impaired adipose tissue capillarization, and inflammation. Circulation. 2011;124:67–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.027813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin AD, Daniel MZ, Drinkwater DT, et al. Adipose tissue density, estimated adipose lipid fraction and whole body adiposity in male cadavers. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994;18:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folkman J, Hochberg M. Self-regulation of growth in three dimensions. J Exp Med. 1973;138:745–753. doi: 10.1084/jem.138.4.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khouri RK, Rigotti G, Cardoso E, et al. Megavolume autologous fat transfer: part I. Theory and principles. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:550–557. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000438044.06387.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khouri RK, Rigotti G, Cardoso E, et al. Megavolume autologous fat transfer: part II. Practice and techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:1369–1377. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carpaneda CA, Ribeiro MT. Percentage of graft viability versus injected volume in adipose autotransplants. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1994;18:17–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00444242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coleman SR. Facial recontouring with lipostructure. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24:347–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sommer B, Sattler G. Current concepts of fat graft survival: histology of aspirated adipose tissue and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:1159–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baran CN, Celebioğlu S, Sensöz O, et al. The behavior of fat grafts in recipient areas with enhanced vascularity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:1646–1651; 1652. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200204150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khouri RK, Eisenmann-Klein M, Cardoso E, et al. Brava and autologous fat transfer is a safe and effective breast augmentation alternative: results of a 6-year, 81-patient, prospective multicenter study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1173–1187. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824a2db6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guyton AC. Interstitial fluid pressure. II. Pressure-volume curves of interstitial space. Circ Res. 1965;16:452–460. doi: 10.1161/01.res.16.5.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Styf J, Körner L, Suurkula M. Intramuscular pressure and muscle blood flow during exercise in chronic compartment syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:301–305. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B2.3818765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milosevic MF, Fyles AW, Hill RP. The relationship between elevated interstitial fluid pressure and blood flow in tumors: a bioengineering analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:1111–1123. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khouri RK, Khouri RK, Jr, Rigotti G, et al. Aesthetic applications of brava-assisted megavolume fat grafting to the breasts: a 9-year, 476-patient, multicenter experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:796–807. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khouri RK, Rigotti G, Khouri RK, Jr, et al. Tissue-engineered breast reconstruction with brava-assisted fat grafting: a 7-year, 488-patient, multicenter experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001039. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Renò F, Sabbatini M, Lombardi F, et al. In vitro mechanical compression induces apoptosis and regulates cytokines release in hypertrophic scars. Wound Repair Regen. 2003;11:331–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agha R, Ogawa R, Pietramaggiori G, et al. A review of the role of mechanical forces in cutaneous wound healing. J Surg Res. 2011;171:700–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu PH, Lew DH, Mayer H, et al. Micro-mechanical forces as a potent stimulator of wound healing. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:57. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heit YI, Lancerotto L, Mesteri I, et al. External volume expansion increases subcutaneous thickness, cell proliferation, and vascular remodeling in a murine model. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:1–8. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc04d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lancerotto L, Chin MS, Freniere B, et al. Mechanisms of action of external volume expansion devices. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:569–578. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829ace30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Khouri RK, Schlenz I, Murphy BJ, et al. Nonsurgical breast enlargement using an external soft-tissue expansion system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:2500–2514. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200006000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sutcliffe MC, Davidson JM. Effect of static stretching on elastin production by porcine aortic smooth muscle cells. Matrix. 1990;10:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8832(11)80163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lujan-Hernandez JR, Lancerotto L, Nabzdyk C, et al. Adipogenesis by External Volume Expansion. New York, New York: PSRC Annual Meeting; 2014. Mar 9, [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ingber DE. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ingber D. How cells (might) sense microgravity. FASEB J. 1999;13(Suppl):S3–S15. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zampell JC, Aschen S, Weitman ES, et al. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis: part I. Adipogenesis, fibrosis, and inflammation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:825–834. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182450b2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aschen S, Zampell JC, Elhadad S, et al. Regulation of adipogenesis by lymphatic fluid stasis: part II. Expression of adipose differentiation genes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:838–847. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182450b47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harvey NL, Srinivasan RS, Dillard ME, et al. Lymphatic vascular defects promoted by Prox1 haploinsufficiency cause adult-onset obesity. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1072–1081. doi: 10.1038/ng1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cronin KJ, Messina A, Knight KR, et al. New murine model of spontaneous autologous tissue engineering, combining an arteriovenous pedicle with matrix materials. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:260–269. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000095942.71618.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dolderer JH, Abberton KM, Thompson EW, et al. Spontaneous large volume adipose tissue generation from a vascularized pedicled fat flap inside a chamber space. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:673–681. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dolderer JH, Thompson EW, Slavin J, et al. Long-term stability of adipose tissue generated from a vascularized pedicled fat flap inside a chamber. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2283–2292. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182131c3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abberton KM, Bortolotto SK, Woods AA, et al. Myogel, a novel, basement membrane-rich, extracellular matrix derived from skeletal muscle, is highly adipogenic in vivo and in vitro. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;188:347–358. doi: 10.1159/000121575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kelly JL, Findlay MW, Knight KR, et al. Contact with existing adipose tissue is inductive for adipogenesis in matrigel. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2041–2047. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stillaert FB, Abberton KM, Keramidaris E, et al. Intrinsics and dynamics of fat grafts: an in vitro study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1155–1162. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ebe224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thomas GP, Hemmrich K, Abberton KM, et al. Zymosan-induced inflammation stimulates neo-adipogenesis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:239–248. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schlenz I, Kaider A. The Brava external tissue expander: is breast enlargement without surgery a reality? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1690–1691. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000267637.43207.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Del Vecchio DA, Bucky LP. Breast augmentation using preexpansion and autologous fat transplantation: a clinical radiographic study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2441–2450. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182050a64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uda H, Sugawara Y, Sarukawa S, et al. Brava and autologous fat grafting for breast reconstruction after cancer surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;133:203–213. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000437256.78327.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smahel J, Meyer VE, Schutz K. Vascular augmentation of free adipose tissue grafts. Eur J Plast Surg. 1990;13:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 75.von Heimburg D, Lemperle G, Dippe B, et al. Free transplantation of fat autografts expanded by tissue expanders in rats. Br J Plast Surg. 1994;47:470–476. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yamaguchi M, Matsumoto F, Bujo H, et al. Revascularization determines volume retention and gene expression by fat grafts in mice. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:742–748. doi: 10.1177/153537020523001007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]