Abstract

Study Design Retrospective cohort study.

Objective Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV) are a common congenital anomaly, and they can be accurately identified on anteroposterior (AP) radiographs of the lumbosacral spine. This study attempts to determine the prevalence of this congenital anomaly and to increase awareness among all clinicians to reduce the risk of surgical and procedural errors in patients with LSTV.

Methods A retrospective review of 5,941 AP and lateral lumbar radiographs was performed. Transitional vertebrae were identified and categorized under the Castellvi classification.

Results The prevalence of LSTV in the study population was 9.9%. Lumbarized S1 and sacralized L5 were seen in 5.8 and 4.1% of patients, respectively.

Conclusion LSTV are a common normal variant and can be a factor in spinal surgery at incorrect levels. It is essential that all clinicians are aware of this common congenital anomaly.

Keywords: lumbosacral, transitional vertebrae, spinal surgery, lumbarization, sacralization

Introduction

There are normal anatomical variants at the L5–S1 vertebral level,1 commonly termed lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV).2 3 LSTV includes both lumbarization of the most superior sacral segment and sacralization of the lowest lumbar segment.4 Lumbarization of the S1 vertebrae includes features such as anomalous articulation, well-formed lumbar type facet joints, a more squared appearance of the vertebrae, and a well-formed, full-sized disk. Sacralization of the L5 vertebrae is characterized by broadened elongated transverse processes to complete fusion to the sacrum.4 5 In the majority of cases, transition is incomplete or unilateral.6

Castellvi et al devised a system to classify varieties of LSTV by using a set of distinguishing morphologic characteristics.5 This system categorizes LSTV into one of four groups: type I, dysplastic transverse process; type II, incomplete lumbarization/sacralization with a unilateral or bilateral pseudarthrosis; type III, complete lumbarization/sacralization; and type IV, mixed. If the morphology differs between the right and the left side, the transition is designated to the side that has the higher type numerically (Figs. 1 and 2).

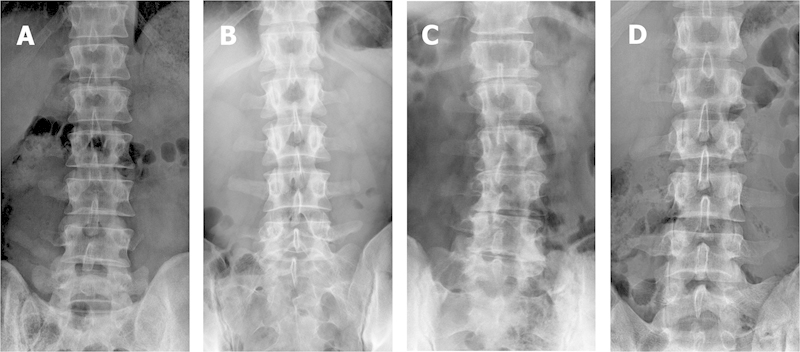

Fig. 1.

Anteroposterior lumbar radiographs. Castellvi classification. (A) Type III lumbarized S1. (B) Type III sacralized L5. (C) Type II sacralized L5. (D) Type IV mixed.

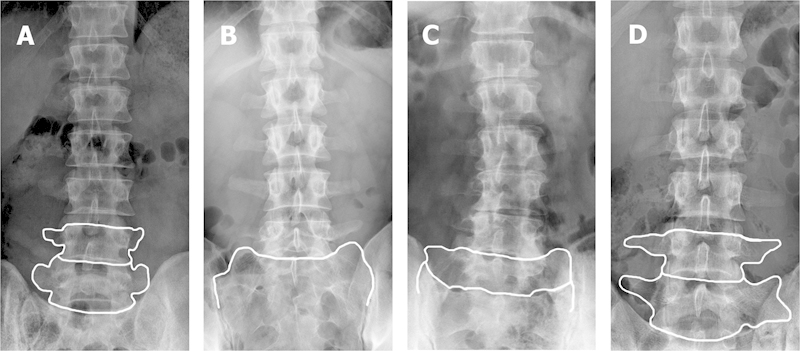

Fig. 2.

Anteroposterior lumbar radiographs with diagrams overlaid to delineate the anatomy of the lumbosacral transitional vertebrae.

There is currently no standardized method established for identifying LSTV.7 Most authors agree LSTV are best seen on anteroposterior (AP) radiographs, although some go further to advocate a Ferguson view (angled cranially at 30 degrees).4 7 8 9 10 A newer method for accurate LSTV identification involves using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to locate the iliolumbar ligaments that are thought to arise exclusively from the L5 transverse processes, as this identifies the vertebral level consistently. However, this method is not as accurate in patients with anomalies at the thoracolumbar junction.4 7 Some authors advocate views of the entire spine to properly distinguish between hypoplastic ribs from lumbar transverse processes and to identify the presence of thoracolumbar transitional vertebrae.1 4

Methods

A retrospective review of 5,941 AP and lateral lumbar X-rays was performed. This was achieved by searching the Princess Alexandra Hospital imaging database AGFA Impax version 5.2. Our search was conducted between October 19, 2010, and March 25, 2012. Patients were imaged for a variety of reasons including post–spinal fusion, vertebral fractures, back pain, radicular pain, and orthopedic and neurosurgical preoperative and postoperative scans. Of the 5,941 images reviewed, 512 patients were excluded because of poor image quality, inadequate exposure of the lumbar spine, or inability to identify transitional vertebrae due to instrumentation or abdominal contents.

We identified transitional vertebrae by counting down from the last thoracic vertebra on the AP X-rays, then if necessary looking at the lateral view for confirmation. If hypoplastic ribs were identified, the vertebra immediately beneath would be designated as L1. Castellvi types II, III, and IV were included as transitional states. Type I LSTV were excluded as they lack clinical and surgical significance.5

Data were recorded as type II to IV. All suspected LSTV were jointly reviewed by three researchers, and a consensus was reached on the classification. Data were deidentified and collated using standardized Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington, United States) spreadsheets and analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Of the 5,429 lumbar radiographs, 540 were identified as having LSTV, giving a prevalence of 9.9%. Lumbarized S1 and sacralized L5 had a prevalence of 5.8% and 4.1%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1. Breakdown of different types of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae.

| Total | Type II | Type III | Type IV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbarized S1 | 315 (5.8%) | 80 (1.5%) | 186 (3.4%) | 49 (0.9%) |

| Sacralized L5 | 225 (4.1%) | 144 (2.7%) | 73 (1.3%) | 8 (0.1%) |

The reporting radiologist identified 30.4% of the cases of LSTV. In 1% of cases, lumbarization of S1 was reported when there was sacralization of L5. In 0.8% of cases, sacralization of L5 was reported when there was lumbarization of S1.

Discussion

Prevalence

To our knowledge, this is the first study to show the prevalence of LSTV in Australia and the largest sample size of LSTV in the world. Nardo et al examined 4,636 radiographs and found the prevalence of LSTV was 18.1%,11 and Tini et al studied 4,000 radiographs and found a prevalence of 6.7%.9 Our results fall between these two studies and are similar to the prevalences reported in other studies.2 3 4 6 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 The reported prevalence of LSTV in the literature varies and has ranged from 4 to 36% since it was first reported in 1977.2 3 4 6 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 This wide variation is likely due to differences in individual diagnostic and classification criteria, observer error, imaging techniques, and confounding factors of the population being studied.6

When comparing these transitional states individually, sacralization of the fifth lumbar vertebrae is more common than lumbarization of the first sacral segment.6 Sacralized L5 has a reported prevalence of 1.7 to 14%, whereas lumbarized S1 has a reported prevalence of 3 to 7%.6 7 14 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 However, three of these studies show lumbarization to be more common than sacralization,20 22 25 which is consistent with our findings. The prevalence of lumbarization and sacralization in our study population was 5.3% and 3.8%, respectively. It is important to note that type I LSTV—vertebrae with broad transverse processes—were not counted as transitional in our study. This may have decreased our recorded prevalence of sacralized transitional states.

Surgical Errors

Spinal surgeons regularly operate at the L5–S1 junction.27 Patients with LSTV pose an issue for spinal surgeons because inconsistencies exist between imaging and patient symptoms.3 4

Errors in numeric identification of the vertebrae have been reported to cause spinal surgery at incorrect levels on numerous occasions, and the incidence of this is undoubtedly higher in patients with LSTV.4 28 To identify patients with LSTV, it is imperative that spinal surgeons order plain lumbar X-rays prior to surgery. Surgical errors are more likely to occur when spinal MRIs are reviewed without accompanying conventional radiographs.29

Although disk surgery performed at the wrong spinal level is uncommon, an error can have significant consequences for the patient.2 30 In patients with cauda equina syndrome or foot drop secondary to spinal canal stenosis or nerve root compression, surgery on the correct spinal level prevents serious morbidity.30 Often patients who have spinal operations at the wrong level must undergo a second operation or they will remain symptomatic. This has obvious detriments for both hospital and patient in terms of monetary cost, ongoing burden of disease, and the potential for postoperative complications. It is critical that spinal surgeons are aware of LSTV to reduce the risk of surgical and procedural errors.3 4 28

Reporting of LSTV

The low number of LSTV reported may be due to observer error or insufficient awareness of transitional lumbosacral anatomy. Consistently reporting LSTV can be difficult for radiologists when different investigations are done at different locations and previous imaging is not available for comparison. It is not essential for radiologists to classify LSTV using the Castellvi classification system, but they should be able to identify a lumbosacral transitional state and describe the anatomy accurately and consistently.

Ultimately, however, the responsibility lies with the spinal surgeon to perform surgery at the correct level, and they need to be confident that they can identify the correct spinal level with preoperative and intraoperative imaging. Where there is confusion, the surgeon should confer with the radiologist to ensure that there is consistency in relation to labeling and documentation.3 Further investigation and potential intervention in the form of nerve root blocks may be of value to confirm that the correct level is operated on.

LSTV and Back Pain

The association between LSTV and back pain has been well documented.31 It was first described by Bertolotti in 191732; however, it stills remains a contentious point nearly a century later.15 16 18 31 32 33 34 35 36 There are studies both supporting and disputing the association between LSTV and back pain.4 Further research is needed to bring consensus on this subject.

Potential Limitations

This study did not analyze imaging that was performed on asymptomatic individuals, so there is a potential selection bias in the study population. It is possible that the prevalence of LSTV in the study population is higher than that in the general population for this reason. However, given that the patients in this study were imaged for several reasons not limited to back pain, the effect on the results should be minor. Observer error when reading films and the differences in diagnostic criteria between researchers and other studies are other limitations to this study. Three researchers independently reviewed all X-rays suspected of having LSTV to reduce these errors.

Conclusion

The prevalence of LSTV in this study sample was 9.9%. LSTV are a common normal variant in the population, which can have significant implications for spinal surgery. It is essential that spinal surgeons and radiologists are aware of LSTV and are highly vigilant for this common anatomical variant.

Footnotes

Disclosures Heath D. French, none Arjuna J. Somasundaram, none Nathan R. Schaefer, none Richard W. Laherty, none

References

- 1.Wigh R E. The thoracolumbar and lumbosacral transitional junctions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1980;5(3):215–222. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198005000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee C H, Park C M, Kim K A. et al. Identification and prediction of transitional vertebrae on imaging studies: anatomical significance of paraspinal structures. Clin Anat. 2007;20(8):905–914. doi: 10.1002/ca.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apazidis A, Ricart P A, Diefenbach C M, Spivak J M. The prevalence of transitional vertebrae in the lumbar spine. Spine J. 2011;11(9):858–862. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konin G P, Walz D M. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: classification, imaging findings, and clinical relevance. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(10):1778–1786. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellvi A E, Goldstein L A, Chan D P. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and their relationship with lumbar extradural defects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1984;9(5):493–495. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198407000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bron J L, van Royen B J, Wuisman P I. The clinical significance of lumbosacral transitional anomalies. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73(6):687–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes R J, Saifuddin A. Numbering of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae on MRI: role of the iliolumbar ligaments. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(1):W59––W65. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinterdorfer P, Parsaei B, Stieglbauer K, Sonnberger M, Fischer J, Wurm G. Segmental innervation in lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV): a comparative clinical and intraoperative EMG study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(7):734–741. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.187633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tini P G, Wieser C, Zinn W M. The transitional vertebra of the lumbosacral spine: its radiological classification, incidence, prevalence, and clinical significance. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1977;16(3):180–185. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/16.3.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes R J, Saifuddin A. Imaging of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae. Clin Radiol. 2004;59(11):984–991. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nardo L, Alizai H, Virayavanich W. et al. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: association with low back pain. Radiology. 2012;265(2):497–503. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delport E G, Cucuzzella T R, Kim N, Marley J, Pruitt C, Delport A G. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae: incidence in a consecutive patient series. Pain Physician. 2006;9(1):53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vergauwen S, Parizel P M, van Breusegem L. et al. Distribution and incidence of degenerative spine changes in patients with a lumbo-sacral transitional vertebra. Eur Spine J. 1997;6(3):168–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01301431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn P Y, Strobel J J, Hahn F J. Verification of lumbosacral segments on MR images: identification of transitional vertebrae. Radiology. 1992;182(2):580–581. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.2.1732988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quinlan J F, Duke D, Eustace S. Bertolotti's syndrome. A cause of back pain in young people. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(9):1183–1186. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B9.17211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterson C K, Bolton J, Hsu W, Wood A. A cross-sectional study comparing pain and disability levels in patients with low back pain with and without transitional lumbosacral vertebrae. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28(8):570–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elster A D. Bertolotti's syndrome revisited. Transitional vertebrae of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14(12):1373–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taskaynatan M A, Izci Y, Ozgul A, Hazneci B, Dursun H, Kalyon T A. Clinical significance of congenital lumbosacral malformations in young male population with prolonged low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(8):E210–E213. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158950.84470.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luoma K, Vehmas T, Raininko R, Luukkonen R, Riihimäki H. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra: relation to disc degeneration and low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29(2):200–205. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000107223.02346.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leboeuf C, Kimber D, White K. Prevalence of spondylolisthesis, transitional anomalies and low intercrestal line in a chiropractic patient population. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1989;12(3):200–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinberg E L, Luger E, Arbel R, Menachem A, Dekel S. A comparative roentgenographic analysis of the lumbar spine in male army recruits with and without lower back pain. Clin Radiol. 2003;58(12):985–989. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(03)00296-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J T, Bahk J H, Sung J. Influence of age and sex on the position of the conus medullaris and Tuffier's line in adults. Anesthesiology. 2003;99(6):1359–1363. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200312000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chithriki M, Jaibaji M, Steele R D. The anatomical relationship of the aortic bifurcation to the lumbar vertebrae: a MRI study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2002;24(5):308–312. doi: 10.1007/s00276-002-0036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santiago F R, Milena G L, Herrera R O, Romero P A, Plazas P G. Morphometry of the lower lumbar vertebrae in patients with and without low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2001;10(3):228–233. doi: 10.1007/s005860100267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peh W C, Siu T H, Chan J H. Determining the lumbar vertebral segments on magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24(17):1852–1855. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199909010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hald H J, Danz B, Schwab R, Burmeister K, Bähren W. [Radiographically demonstrable spinal changes in asymptomatic young men] Rofo. 1995;163(1):4–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1015936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rengachary S S Ellenbogen R G Principles of Neurosurgery 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wigh R E, Anthony H F Jr. Transitional lumbosacral discs. Probability of herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1981;6(2):168–171. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198103000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Driscoll C M, Irwin A, Saifuddin A. Variations in morphology of the lumbosacral junction on sagittal MRI: correlation with plain radiography. Skeletal Radiol. 1996;25(3):225–230. doi: 10.1007/s002560050069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malanga G A, Cooke P M. Segmental anomaly leading to wrong level disc surgery in cauda equina syndrome. Pain Physician. 2004;7(1):107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahato N K. Relationship of sacral articular surfaces and gender with occurrence of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae. Spine J. 2011;11(10):961–965. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertolotti M. Contributo alla conoscenza dei vizi di differenzazione regionale del rachide con speciale reguardo all assimilazione sacrale della V. lombare. Radiol Med (Torino) 1917;4:113–144. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stinchfiled F E, Sinton W A, Conn D. Clinical significance of the transitional lumbosacral vertebra: relationship to back pain, disk diseases, and sciatica. JAMA. 1955;157(13):1107–1109. doi: 10.1001/jama.1955.02950300035007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paraskevas G, Tzaveas A, Koutras G, Natsis K. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra causing Bertolotti's syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2009;2:8320. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-8320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olofin M UE, Noronha C, Okanlawon A. Incidence of lumbosacral transitional vertebrae in low back pain patients. West African J Radiol. 2001;8:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Tulder M W, Assendelft W J, Koes B W, Bouter L M. Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of observational studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22(4):427–434. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199702150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]