Abstract

Introduction

Activated platelets shed microparticles from plasma membranes, but also release smaller exosomes from internal compartments. While microparticles participate in athero-thrombosis, little is known of exosomes in this process.

Materials & Methods

Ex vivo biochemical experiments with human platelets and exosomes, and FeCl3-induced murine carotid artery thrombosis.

Results

Both microparticles and exosomes were abundant in human plasma. Platelet-derived exosomes suppressed ex vivo platelet aggregation and reduced adhesion to collagen-coated microfluidic channels at high shear. Injected exosomes inhibited occlusive thrombosis in FeCl3-damaged murine carotid arteries. Control platelets infused into irradiated, thrombocytopenic mice reconstituted thrombosis in damaged carotid arteries, but failed to do so after prior ex vivo incubation with exosomes. CD36 promotes platelet activation, and exosomes dramatically reduced platelet CD36. CD36 is also expressed by macrophages where it binds and internalizes oxidized LDL and microparticles, supplying lipid to promote foam cell formation. Platelet exosomes inhibited oxidized-LDL binding and cholesterol loading into macrophages. Exosomes were not competitive CD36 ligands, but instead sharply reduced total macrophage CD36 content. Exosomal proteins, in contrast to microparticle or cellular proteins, were highly adducted by ubiquitin. Exosomes enhanced ubiquitination of cellular proteins, including CD36, and blockade of proteosome proteolysis with MG-132 rescued CD36 expression. Recombinant unanchored K48 poly-ubiquitin behaved similarly to exosomes, inhibiting platelet function, macrophage CD36 expression, and macrophage particle uptake.

Conclusions

Platelet-derived exosomes inhibit athero-thrombotic processes by reducing CD36-dependent lipid loading of macrophages and by suppressing platelet thrombosis. Exosomes increase protein ubiquitination, and enhance proteasome degradation of CD36.

Keywords: Thrombosis, Platelets, Cell-Derived Microparticles, CD36 Protein, Exosomes

Introduction

Exosomes are small (~50 nm) particles derived from multi-vesiculated endosomes released by exocytosis from most nucleated cells [1]. Exosomes contain cytokine receptors, tumor-associated antigens, mRNA, and miRNA [1], and are able to transfer these molecules to recipient cells, orchestrating local and systemic events. Platelets also release exosomes [2] and, while they have been little studied, platelet-derived exosomes induce endothelial cell apoptosis [3] and circulate in patients during septic shock where they promote myocardial dysfunction [4].

Microparticles are larger than exosomes and are derived from the plasma membrane. Microparticles contribute to thrombosis by presenting tissue factor along with anionic phospholipids that serve as a surface for assembly of coagulation enzymes. Microparticles are ligands of the type II scavenger receptor CD36 [5], enhancing platelet intracellular signaling. CD36 ligand binding and signaling aids platelet aggregation that contributes to atherothrombosis [6–8]. CD36 also binds lipids [9–12], thrombospondins [13, 14], and oxidized lipoproteins [10], and is an important contributor of lipids for macrophage progression to foam cell formation and atherogenesis [11, 15].

Activated platelets release both exosomes and microparticles [2], which we find to differentially affect platelet function. Exosomes attenuated platelet aggregation and adhesion to a collagen matrix ex vivo, and exosomes suppressed occlusive thrombosis in a FeCl3-induced arterial injury model by reducing platelet reactivity. Exosomes rapidly decreased CD36 in platelets and macrophages through enhanced ubiquitination and proteasome degradation. We conclude exosomes mitigate atherothrombotic process by acting on both macrophages and platelets, elucidating potential new therapeutic targets for this disease process.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Reagents were from: collagen, Chrono-Log Corporation (Havertown, PA); phosphorylated and total JNK1/2 antibodies, Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); rabbit anti-CD36, Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO); monoclonal or IgA anti-CD36, Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); monoclonal anti-poly-ubiquitin P4D1, and HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; recombinant K48 (3–7) poly-ubiquitin, Boston Biochem (Cambridge, MA); Alexa488 conjugated anti-species secondary antibodies, Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY); pre-cast gels, Bio-Rad. LDL was isolated from human plasma and oxidized with myeloperoxidase [16, 17]. Murine Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells (CRL-1642), and B16-F1 (CRL-6323) and B16-F10 (CRL-6475) mouse melanoma cells were from ATCC. Other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell preparation

Human platelets were isolated from platelet-rich plasma [18] in a protocol approved by the Cleveland Clinic IRB. Briefly, platelet-rich plasma was filtered through two layers of 5-μm mesh (BioDesign) to remove nucleated cells and centrifuged (500 × g, 20 min) in 100 nM PGE1. Platelet pellets were re-suspended in 50 ml 5 mM PIPES, 145 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 50 μM Na2HPO4, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5.5 mM glucose, 100 nM PGE1 before centrifugation (500 × g, 20 min) twice before re-suspending in 0.5% human serum albumin in HBSS. Murine studies were approved by the Cleveland Clinic IACUC. Murine macrophages were obtained by peritoneal lavage 4 days after injection with thioglycollate and adherent cells were maintained in culture.

Exosomes and microparticle isolation

Platelets were activated with 0.01U thrombin overnight in PBS or 10 μm calcium ionophore A23187 (Sigma) for 1 h in PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and MgCl2. Microparticles and exosomes were isolated by differential centrifugation (17, 000 x g for 90 min, then 110,000 x g for 2hr). Exosomes from untreated cancer cells were isolated in this way after low speed centrifugation (2,000 x g). Exosome pellets were washed and re-suspended in PBS, and used immediately or stored up to 1 week at 4°C. Some platelets were treated with 100 μM tert-butylhydroperoxide for 1 h to generate oxidized microparticles and exosomes. The floatation density of exosomes in a continuous sucrose gradient was verified as described [19]. Microparticle and exosome protein was determined by DC® Protein (Bio-Rad) and used to calculate plasma concentrations assuming no material loss during preparation.

In vitro thrombogenesis

Microfluidic flow chambers (Vena8 Fluoro biochips, Cellix) were coated with collagen (100 μg/ml) overnight at 4°C. Whole blood was collected in sodium citrate, incubated with calcein-AM (1 μm) for 30 min, and then exposed to platelet exosomes (50 μg/ml) or microparticles for 1 h prior to perfusion over the chips at a shear rate of 67.5 dynes cm−2 for 5 min. Unattached cells were then removed by flowing PBS for 30 sec before adherent platelets were visualized by microscopy. Cell images (n=3) from 10 fields were captured and quantified using ImageJ software.

Platelet aggregation

Turbidimetric assays quantified platelet aggregation after incubation with buffer, exosomes, or microparticles in a dual channel aggregometer (Chrono-log Corp.). Collagen (3 μg/ml), ADP (up to 10 μm) or thrombin (0.2 U) were used to initiate aggregation with constant stirring (600 rpm).

Carotid artery thrombosis

C57Bl/6 mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) before the right jugular vein and the left carotid arteries were exposed by mid-line cervical incision. These mice were then injected with 50 μg purified platelet-derived exosomes 10 min prior to induction of thrombosis in the left carotid artery by ectopic application of 7.5% FeCl3 for 1 min [20]. Alternatively, six week old mice were cesium irradiated (11 Gray) to induce thrombocytopenia. Five days later 109 washed platelets from donor mice were fluorescently labeled with 100 μl rhodamine 6G (0.5 mg/ml) and then treated for 2 h with PBS or platelet-derived exosomes (50 μg/ml) ex vivo. Platelets were then injection into the right jugular vein of surgically prepared thrombocytopenic recipient mice 10 min prior to initiation of thrombosis. Thrombus formation was observed in real-time under a water immersion objective at 10 X magnification by intra-vital microscopy. Time to occlusive thrombosis, defined by complete cessation of fluorescent platelet flow, was determined offline using video images captured with a QImaging Retigo Exi 12-bit mono digital camera (Surrey, Canada) and Streampix version 3.17.2 software (Norpix, Montreal, Canada). The end points were set as either cessation of blood flow for >30 seconds or no occlusion after 30 min (three times longer than the average occlusion time), in which case the time was recorded as 30 min for statistical comparison.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

RAW macrophages were seeded on chamber slides in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS. Attached cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde and then incubated with anti-CD36 IgA followed by Alexa488-labeled anti-mouse. Cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI before laser confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy

Platelet-derived microparticles or exosomes were stained with P4D1 anti-poly-ubiquitin monoclonal antibody and Alexa594-conjugated secondary antibody, incubated in a glass bottomed microwell (MatTek) dish for 30 min, and then imaged at 100X by Total Internal Reflection Microscopy with a 1.46 N.A. objective in a Leica AM TIRF MC System (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an ImageEM C9100-13 EMCCD camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, N.J). The 10-mW diode laser was used for excitation and the penetration depth was set to 70 nm.

Flow cytometry

Macrophages or platelets treated with or without exosomes or poly-ubiquitin were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then incubated with anti-CD36 IgA followed by Alexa488-labelled anti-mouse antibody. The cells were pelleted, washed, and fluorescence in the platelet gate was assessed by flow cytomtery before the relative fluorescence intensity histograms were analyzed with Flow Jo software (version 7.2.4; Tree Star Inc.). Microparticle uptake was assessed by labeling microparticles with calcein-AM prior to incubation with macrophages pre-treated, or not, with exosomes or poly-ubiquitin. Acquired fluorescence in a macrophage gate was analyzed with Flow Jo software.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Platelet-derived exosomes and microparticles were isolated by differential centrifugation and re-suspended in 2% paraformaldehyde. Fixed vesicles (5–10μl) were transferred to formvar-coated EM grids, incubated at room temperature for 20 min, and then transferred to parafilm containing 200 μl drops of PBS and washed (3 times, 3 min). The grids were transferred to PBS/50 mM glycine, washed thrice (3 min) before contrasting with uranyl oxalate solution (pH 7.0) for 5 min followed by 4% uranyl acetate and 2% methyl cellulose 1:10 (v/v) for 10 min on ice. Grids were air-dried for 10 min before electron microscopy (Tecnai G2 Spirit BT) at 60 kV.

Oxidized LDL uptake and foam cell formation

Peritoneal macrophages were pre-treated with or without platelet exosomes for 30 min and incubatedwith DiI-labeled NO2LDL [21] (10 μg/ml) for 60 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde before fluorescent confocal microscopy. Total cellular cholesterol content was assessed with a kit from Cayman Chemical.

Expression of data and statistics

All assays were performed in triplicate with experiments performed at least three times with microparticles and exosomes isolated from different donors. The standard deviation and standard errors of the mean from all experiments are presented as error bars. Graphing of figures and statistical analyses were generated with Prism4 (GraphPad Software). A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Exosomes inhibit thrombosis in vivo through reduced platelet activity

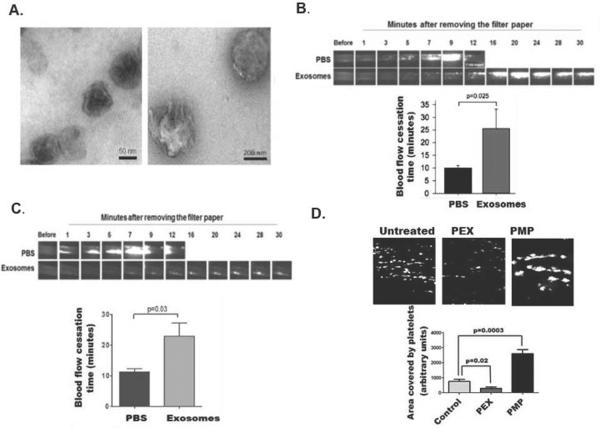

We quantified particle number in human blood by recovering microparticles and exosomes by differential centrifugation, taking advantage of their differing physical sizes. Transmission electron microscopy showed platelet-derived exosomes were sealed vesicles centered in size around 50±30 nanometers (Fig. 1A left). Plasma membrane-derived microparticles were significantly larger, and developed membrane protrusions (Fig. 1A right). We confirmed exosomes were proteolipid particles that floated in a sucrose density gradient at 1.17 g/ml (not shown).

Figure1. Platelet exosomes are anti-thrombotic and inhibit platelet adhesion.

A) Transmission electron microscopy of platelet-derived exosomes and microparticles. Platelets were stimulated with A23187 and removed by low speed centrifugation before microparticles and exosomes were isolated by differential centrifugation as stated in “Methods.” Photomicrographs of exosomes and microparticles are magnified 98,000× and 68,000×, respectively, with 50 and 200 nmeter scale bars. B) Exosomes prolong arterial occlusion time after FeCl3 induced injury. Exosomes (50 μg) were injected into wild type mice through the jugular vein along with Rhodamine 6G to fluorescently label platelets. Thrombosis was induced 10 min later by topical application of filter paper saturated with 7.5% FeCl3 to murine carotid arteries for 1 min. Time to complete cessation of blood flow was determined by intravital microscopy (n=3 experimental, 4 control; *p≤ 0.025). C) Exosome-treated platelets fail to effectively reconstitute occlusive thrombosis in FeCl3 damaged carotid arteries. Murine platelets were incubated with PBS or 50 μg/ml platelet-derived exosomes for 2 h and labeled with Rhodamine 6G. Sufficient treated platelets (109) were injected through the jugular vein into mice previously rendered thrombocytopenic by γ-irradiation to reconstitute platelet numbers [49]. Thrombosis was induced 10 min later by FeCl3 as in the preceding panel before the time to complete cessation of blood flow was determined by intravital microscopy (n=4 experimental, 4 control; *p≤ 0.03). D) Exosomes inhibit platelet ex vivo adhesion to collagen at high shear. Calcein-labeled whole human blood with was treated with buffer, exosomes (50 μg/ml), or microparticles (50 μg/ml), and then flowed through collagen-coated microchannels using the Vena8 Fluoro system (Cellix) at 67.5 dynes cm−2. Representative images of immobilized fluorescent platelets in the distal image frame (top) and fluorescent intensities quantified by ImageJ (bottom). PEX, platelet-derived exosomes; PMP, platelet-derived microparticles.

The amount of the two particles was quantified by DC® Protein (Bio-Rad) after differential high speed centrifugation and washing. Particle content was calculated using the initial plasma volume and assumed complete recovery. This physical approach showed exosomes circulated at an average concentration of 5.2±1.7 μg/ml and microparticles at a concentration of 13.5±7.7 μg/ml in normal plasma samples (n=5).

Exosomes were anti-thrombotic when examined in a standard model of in vivo thrombosis induced by a brief application of FeCl3 to the surface of an exposed carotid artery [20]. Injection of purified exosomes (50 μg) 10 min prior to induction of thrombosis significantly (p=0.025) delayed platelet accumulation and development of complete occlusion at the site of vascular injury (Fig. 1B). Platelets were the cells affected by exosomes because purified platelets treated ex vivo with purified platelet-derived exosomes prior to infusion into mice previously rendered thrombocytopenic were unable (p=0.03) to successfully reconstitute thrombosis (Fig. 1C). In contrast, buffer treated platelets fully reconstituted thrombosis such that the time to occlusion in these reconstituted thrombocytopenic mice was identical to that of control mice (compare Figs 1B and 1C).

Circulating platelets adhere to the exposed collagen matrix of damaged vessels, which can be modeled ex vivo by flowing fluorescently-labeled platelets in whole human blood at arterial shear rates (67.5 dynes cm−2) through microfluidic channels coated with collagen. Platelet-derived exosomes (50 μg/ml) significantly (p=0.02) reduced platelet adhesion to the coated chamber walls (Fig. 1D). In contrast, platelet-derived microparticles significantly enhanced deposition of large platelet aggregates onto the collagen-coated channels (p<0.0003). We conclude exosomes suppress thrombosis by inhibiting platelet function.

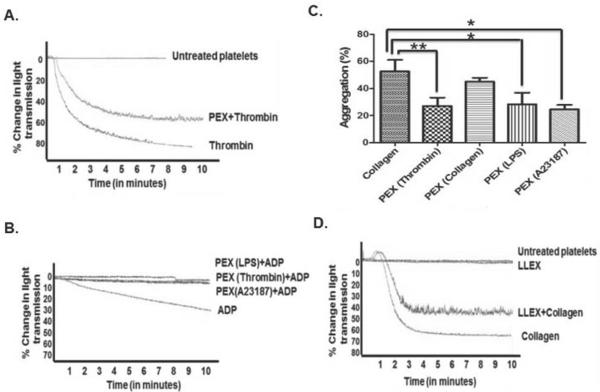

Exosomes from diverse sources reduce ex vivo platelet aggregation

Exosomes isolated from A23187-stimulated platelets did not themselves induce a change in platelet shape, nor promote aggregation when added to quiescent, purified platelets (Fig. 2A). Platelet-derived exosomes, however, did reduce the extent of aggregation by these platelets after thrombin stimulation. Exosomes isolated from platelets stimulated by various agonists suppressed aggregation induced by sub-optimal amounts of ADP in platelet-rich plasma (Fig. 2B), although not by maximally effective ADP concentrations (not shown). Similarly, adhesion of washed platelets in response to collagen was reduced by exosomes derived from thrombin-, lipopolysaccharide- or A23187-stimulated platelets, although the reduction in aggregation by exosomes from collagen-treated platelets was not statistically significant (Fig. 2C). Additionally, exosomes derived from Lewis lung carcinoma cells suppressed collagen-induced aggregation (Fig. 2D), so reduction of platelet reactivity is a general response to exosomes.

Figure 2. Platelet exosomes inhibit platelet function.

A) Exosomes inhibit collagen-induced platelet aggregation. Washed human platelets were incubated with buffer or exosomes (50 μg/ml) derived from A23187-activated platelets before aggregation was initiated with 0.1U thrombin with stirring. Tracings are representative of 3 independent experiments. B) Exosomes from A23187-, thrombin- or LPS-stimulated platelets were incubated with human platelet rich plasma before aggregation was initiated with ADP (2 μM). Tracings are representative of 3 independent experiments. C) Exosomes from platelets activated by varied stimuli inhibit collagen-induced aggregation. Washed human platelets were incubated for 1h with buffer or 50 μg/ml exosomes isolated from platelets stimulated by the stated agonists prior to initiation of aggregation by 3 μg/ml collagen. * p<0.05 ** p< 0.01 D) Cancer cell-derived exosomes reduce platelet aggregation. Washed human platelets incubated (1 h) with exosomes spontaneously released from Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells (LLEX) were stimulated with collagen (3 μg/ml) to initiate aggregation.

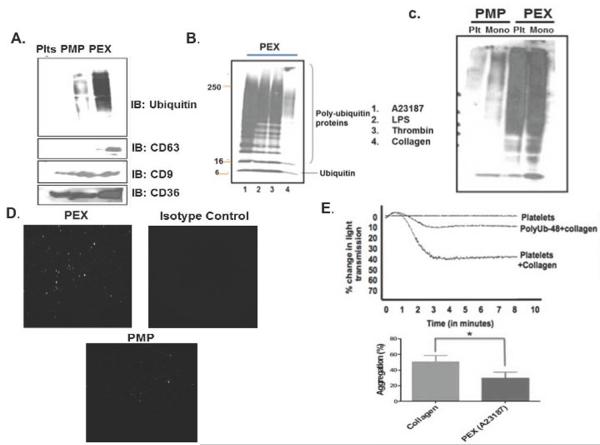

Platelet exosomes contain poly-ubiquitin, and recombinant poly-ubiquitin down-modulates platelet aggregation

Proteins in exosomes released from nucleated cells are adducted with poly-ubiquitin chains [22–24], as were the proteins of platelet-derived exosomes (Fig. 3A). Ubiquitin conjugates were far more abundant in exosomes relative to either platelets themselves or platelet-derived microparticles. Exosomes were enriched with the tetraspanin Lysosome-Associated Membrane Glycoprotein (CD63), while the tetraspanin CD9 and the CD36 receptor were common among exosomes, microparticles and platelets. The level of ubiquitin adduction of exosomal proteins varied with the inciting agonist, with particles shed from A23187-stimulated cells being most ubiquitinated, followed by those from thrombin- or lipopolysaccharide-stimulated platelets (Fig. 3B). Particles released after collagen stimulation were, in contrast, only weakly adducted by ubiquitin. A similar enrichment of ubiquitinated proteins in exosomes relative to microparticles was also apparent in particles released from monocyte-derived macrophages (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Exosomal proteins are ubiquitinated, and recombinant poly-ubiquitin suppresses platelet aggregation.

A) Platelet exosomal proteins are adducted by ubiquitin. Proteins from platelets, exosomes (PEX), or microparticles (PMP) were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and separately immunoblotted (IB) with anti-ubiquitin P4D1 antibody that recognizes free and polymeric ubiquitin, anti-CD63, anti-CD9, or anti-CD36 before antibody detection by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. B) The proteome of exosomes derived from platelets stimulated with varied agonists are differentially conjugated with polyubiquitin. Proteins extracted from exosomes prepared from platelets stimulated with the stated agonists were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with P4D1 antibody to detect ubiquitin modification. C) Exosomes from human platelets and monocytes are ubiquitinated and distinct from their microparticles. Exosomes and microparticles were isolated by differential centrifugation and ubiquitin conjugation of their proteomes determined by western blotting as in the preceding panel. D) Exosomes contain surface-exposed ubiquitin. Exosomes or microparticles from activated platelets were allowed to adhere to a glass surface and stained with anti-ubiquitin antibody P4D1, or a non-immune isotype antibody, and they with Alexa594-conjugated secondary antibody to detect surface exposed ubiquitin by Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence microscopy. E) Recombinant K48 poly-ubiquitin reduces collagen-stimulated platelet aggregation. Washed platelets were incubated with 5 μg/ml recombinant poly-ubiquitin polymerized through lysine 48 prior to treatment with 3 μg/ml collagen to stimulate homotypic aggregation. The tracing is representative of 3 independent experiments and inhibition was significant. * p<0.05.

We used Total Internal Reflection (TIRF) microscopy to show that at least a portion of the ubiquitin conjugate was displayed on the exosomal surface. TIRF detects—but does not image—fluorophores over the 50 nanometer average diameter of exosomes, with no detectable fluorescence beyond 70 nanometers. Anti-ubiquitin antibody P4D1 ligated ubiquitin in intact exosomes, while microparticles deficient in ubiquitin adducts were not detected by exogenous antibody (Fig. 3D).

We determined whether this poly-ubiquitin was relevant to platelet inhibition. We found recombinant poly-ubiquitin, like exosomes, effectively inhibited collagen-induced aggregation (Fig. 3E). Suppression of aggregation was greater than 50% and was significant. Notably, this recombinant poly-ubiquitin was unconjugated to protein, i.e. unanchored poly-ubiquitin, eliminating a role for the protein component of ubiquitin adducted proteins.

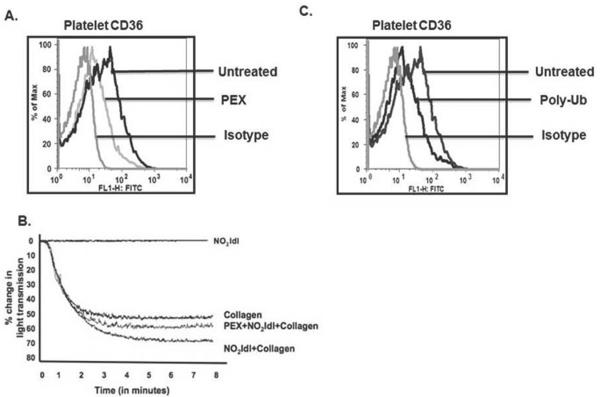

Exosomes and poly-ubiquitin suppress platelet CD36 expression and function

Platelets express CD36 that augments signaling and promotes thrombus formation in a ligand-dependent manner [25]. We found the amount of CD36 displayed on the platelet surface was significantly reduced by exosome exposure (Fig. 4A). The functional significance of this event was demonstrated by a reduction in collagen-mediated platelet aggregation that had been augmented by the CD36-specific ligand NO2LDL (Fig. 4B). We determined whether ubiquitin was responsible for this event by treating platelets with recombinant poly-ubiquitin. This polymer also suppressed CD36 expression on the surface of quiescent platelets (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Exosomes reduce platelet CD36 expression and cargo internalization.

A) Exosomes suppress platelet CD36 surface expression. Washed platelets were treated with platelet-derived exosomes (PEX, 50 μg/ml) before surface CD36 was assessed by flow cytometry relative to platelets stained with isotype control antibody or left unstained. B) NO2-LDL-enhanced platelet aggregation was suppressed by exosomes. The CD36 agonist NO2-LDL enhanced, but did not stimulate, collagen-induced platelet aggregation. Exosome pre-incubation (50 μg/ml, 1h) reduced aggregation enhanced by NO2-LDL. C. Recombinant poly-ubiquitin suppressed platelet CD36 expression. Washed platelets were treated with 1 μg/ml unconjugated poly-K48 (3–7) ubiquitin or with the non-immune control antibody from panel A before CD36 expression was assessed by flow cytometry.

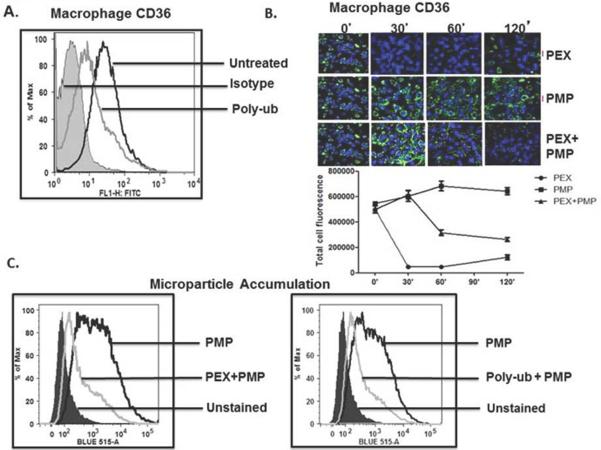

Exosomes and poly-ubiquitin suppress macrophage CD36 expression and microparticle internalization

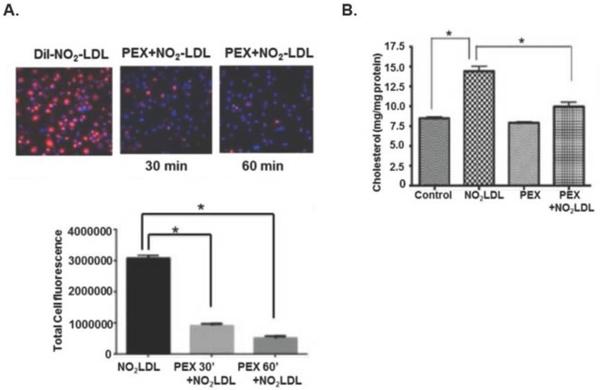

CD36 is also abundantly displayed on macrophages where it acts as a signaling molecule, but also scavenges and internalizes oxidized LDL [26–28] and microparticles [5] that contribute to foam cell formation and atherosclerosis. We found that recombinant poly-ubiquitin (Fig. 5A) or purified platelet exosomes (Fig. 5B) greatly reduced CD36 expression on the macrophage surface. Exosome-induced loss of surface CD36 was rapid, with a maximal effect by 30 min, and was sustained for at least 2 hours (Fig 5B top). Platelet-derived microparticles did not similarly reduce macrophage CD36 surface expression (Fig, 5B middle), so loss of CD36 protein did not result from simple ligand-induced internalization. The combination of exosomes and microparticles had an intermediate effect and caused a slow decline in CD36 over the 2 h of the experiment (Fig. 5B lower). Accordingly, platelet-derived exosomes or recombinant polyubiquitin reduced uptake of platelet microparticles (Fig. 5C) or fluorescently-labeled NO2LDL (Fig 6A) that are CD36 cargos. Again, reduction was rapid with observable effects by 30 min. Unlike NO2LDL, exosomes themselves did not contribute to macrophage cholesterol loading, showing exosomes were not internalized. These particles did, however, reduce cholesterol loading in macrophages ingesting NO2LDL (Fig. 6B).

Figure 5. Exosomes reduce macrophage CD36 expression and microparticle internalization.

A) Unanchored poly-ubiquitin reduces macrophage CD36 surface expression. RAW macrophages were treated, or not, with 1 μg/ml recombinant poly-ubiquitin (poly-ub) for 1 h before surface CD36 was determined by flow cytometry relative to the fluorescence of untreated cells or those stained with control antibody. B) Temporal suppression of macrophage CD36 by exosomes. Cultured macrophages were treated with platelet-derived exosomes (PEX), microparticles (PMP), or both for the stated times before CD36 expressed on unpermeabilized cells was visualized by Alex488-labeled anti-CD36 that fluoresces green. Nuclei of immobilized cells were counterstained with DAPI fluorescing blue. The total green fluorescence of 6 images at each stated time was quantitated by ImageJ (below). C) Exosomes or recombinant polyubiquitin reduces microparticle accumulation by RAW macrophages. Platelet-derived microparticles were fluorescently labeled with calcein-AM, washed, and then incubated with RAW macrophages for 1 h in the presence or absence of 50 μg/ml exosomes (left) or 1 μg/ml poly-ubiquitin (right) prior to analysis of surface CD36 by flow cytometry. Histograms are representative of two independent blood donors.

Figure 6. Exosomes reduce lipid accumulation by macrophages from lipid-rich particles.

A) Exosomes reduce macrophage accumulation of NO2 oxidized LDL. RAW macrophages were incubated with fluorescently DiI-labeled NO2 oxidized LDL with or without platelet-derived exosomes for 30 or 60 min before fluorescent dye accumulation was imaged and quantitated by ImageJ n=3, * p<0.05. B) Macrophage lipid loading by NO2-LDL is reduced by exosomes. The CD36-specific ligand NO2-oxidized LDL was incubated with RAW macrophages in the presence or absence of 50 μg/ml platelet exosomes overnight and washed before total cellular cholesterol content was quantified. n=3, * p<0.05

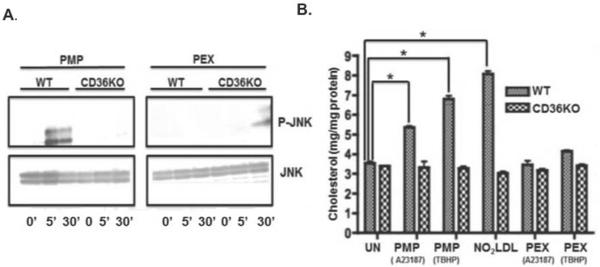

Exosomes suppress CD36 signaling

CD36 recruits the JNK MAP kinase [5] necessary for macrophage foam cell transformation [11, 25]. Platelet-derived microparticles stimulated JNK phosphorylation in thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages derived from wild-type C57BL6 mice, but failed to do so in macrophages derived from CD36 null animals (Fig. 7A). In contrast, exosomes did not induce JNK phosphorylation in either cell type at any time. Loss of CD36, as expected, reduced macrophage cholesterol accumulation following incubation with either oxidized LDL or platelet microparticles (Fig. 7B). Oxidation of microparticles with tert-butylhydroperoxide increased the amount of oxidized phospholipid CD36 ligands in lipoprotein particles [29], and increased CD36-dependent accumulation of microparticle cholesterol (Fig. 7B). Platelet exosomes, in contrast, did not increase cellular cholesterol in either wild-type or CD36 null macrophages, nor did oxidation convert exosomes to CD36 ligands. These data show platelet-derived exosomes are neither CD36 agonists nor cargoes.

Figure 7. Exosomes do not activate CD36 signaling, nor are accumulated by macrophages.

A) Platelet JNK phosphorylation is induced by microparticles, but not exosomes, through CD36. Cultured monocyte-derived macrophages from C57BL6 wild-type or CD36 null mice were treated with 50 μg/ml platelet-derived microparticles (left) or exosomes (right) for the stated times before cellular proteins were resolved and western blotted for phospho-JNK or total JNK. B) NO2 oxidized LDL (NO2-LDL) or microparticles, but not exosomes, increase macrophage cholesterol content. Elicited peritoneal macrophages from wild-type or CD36 null mice were incubated overnight with Ca++ ionophore-elicited platelet microparticles, oxidized LDL, or ionophore-elicited exosomes. In some incubations, the particles were s oxidized by 100 μM tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP) prior to incubation with macrophages. Total cellular cholesterol was determined as described in “Methods.” n=3, * p<0.05.

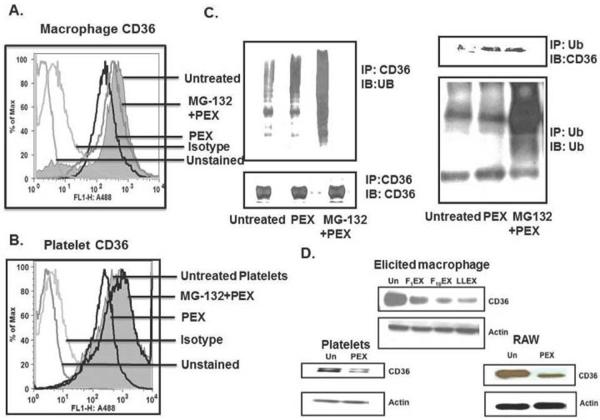

Proteasome inhibition preserves CD36 expression from exosome-induced suppression

Transfected CD36 is regulated in nucleated cell lines by incorporation of ubiquitin followed by proteasome degradation [30]. We found the proteosome inhibitor MG-132 ameliorated loss of native CD36 from the surface of macrophages incubated with platelet-derived exosomes (Fig. 8A). MG-132 also suppressed loss of CD36 from the surface of platelets induced by exosomes (Fig. 8B). This suggests CD36 is a proteasome substrate in platelets and macrophages, and so likely was marked for proteolysis by ubiquitination. Immunoprecipitation of macrophage CD36 followed by immunoblotting for ubiquitin showed macrophage CD36 normally is adducted by ubiquitin (Fig. 8C). This decoration was modestly increased by incubation with exosomes, but was greatly increased by inhibition of proteasome proteolysis with MG-132. Similar results were observed with the converse experiment where ubiquitin was first immunoprecipitated and then blotted with anti-CD36. We found (Fig. 8D) that exosomes from two melanoma cell lines (F1, F10), as well as Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells, reduced total cellular CD36 in thioglycolate-elicited peritoneal macrophages. Platelet exosomes also reduced total CD36 protein content in platelets and RAW macrophages. Thus, exosomes from varied sources reduce total and surface CD36 in macrophages and platelets through ubiquitination followed by proteasome degradation.

Figure 8. Exosomes increase CD36 ubiquitination and proteasome degradation.

Macrophage (A) or platelet (B) surface CD36 was quantified by flow cytometry after exposure to platelet exosomes (50 μg/ml) for 1 following pretreatment, or not, with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (10 μM). The comparison is to isotype control antibody or unstained cells C) Macrophage CD36 ubiquitination increases after exosome or MG-132 exposure. Control or exosome- (50 μg/ml; 60 min) treated RAW macrophages were pretreated or not with 10 μM MG-132 for 1 h and then lysed. Lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-CD36 antibody (left), resolved by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-ubiquitin (UB) (top) or for total CD36 (bottom). Conversely, ubiquitin-macrophage conjugates were precipitated with anti-ubiquitin antibody (right) and then probed with anti-CD36 antibody (top) or anti-ubiquitin P4D1 antibody (bottom). D) Exosomes reduce total cellular CD36. Protein lysates from thioglycolate-elicited macrophages treated with or without exosomes derived from either F1 (F1EX) or F10 (F10EX) melanoma cells or Lewis Lung Carcinoma cells (LLEX) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-CD36 (top) and then re-probed with anti-β-actin. Lysates from platelets (bottom left) and the RAW264.7 macrophage cell line (bottom right) were similarly analyzed.

Discussion

Our findings elucidate an unanticipated activity of exosomes in suppressing occlusive thrombosis in damaged coronary arteries. Ferric chloride induces transmural endothelial cell oxidation and death with rapid platelet adhesion at the site of injury that ultimately occludes the carotid artery [20], although various murine models emphasized distinct elements of the process [44, 45]. Identifying platelets as the target cell in vivo is difficult since the tools of modern molecular biology generally do not apply to anucleate platelets. However, manipulating purified platelets ex vivo prior to infusion, when the inhibition is long lived, into thrombocytopenic recipient mice shows that platelets can be specifically analyzed in a complex in vivo model. The defective reconstitution of occlusive thrombosis in animals receiving exosome-exposed platelets proves platelets are a physiologic target sensitive to exosome exposure. This outcome, and the ability of exosomes to reduce platelet activation in platelet-rich plasma, shows plasma proteins do not protect platelets from exosome exposure.

Stimulated platelets release both exosomes and microparticles [2], and transmission electron microscopy and western blotting showed the two types of particles were distinct. Enumerating micron-sized plasma microparticles is problematic [31, 32], and the diameter of exosomes is smaller than the wavelength of visible light, further obfuscating particle quantitation. To circumvent difficulties posed by particle size, we physically separated the differently sized particles followed by protein quantitation. Both particles were normally present in the circulation, and their abundance was different by just 2.5-fold. The effect of these two types of particles on platelets and monocytic cells, however, was diametrically opposed.

Exosomes of nucleated cells are enriched with ubiquitin [33] and ubiquitinated proteins [23, 33], and are nature's most conserved carriers of extracellular ubiquitin [1, 34]. The immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties of exosomes may relate to this ubiquitin [22–24], and free ubiquitin inhibits select immune events [35]. Platelets also modify their proteins with ubiquitin, and exosomes shed from stimulated platelets were extensively adducted by ubiquitin. Platelets contain a functional ubiquitin/proteasome system [36, 37] that controls their high avidity responses to thrombin [38], and we now find rapidly modifies and degrades CD36. Ubiquitin availability in platelets may be limiting because exosome accumulation by platelets (Supplementary Fig. 1) increased ubiquitination of platelet proteins (Supplementary Fig. 2). MG-132 enhanced this ubiquitination (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating exosomal ubiquitin contributes to the ubiquitin cycle. Extracellular ubiquitin can participate in platelet ubiquitin metabolism since recombinant poly-ubiquitin also reduced platelet reactivity. Notably, this polyubiquitin was unanchored, that is, not conjugated to protein. Protein-free poly-ubiquitin does exist and may have a role in innate immunity [39] as well as kinase activation [40].

Exosomes or recombinant poly-ubiquitin suppressed CD36 signaling in platelets, and particle and lipid accumulation by monocytes and macrophages. Loss of CD36 in macrophages was prolonged, but began to recover 2h after exposure. Platelets, in contrast, do not synthesize CD36 and would remain altered by exosome exposure. CD36 expression varies significantly in the human population, in part through inherited genetic polymorphisms [41, 42], that affects susceptibility to the CD36 ligand Plasmodium falciparum [43] and modulates platelet responsiveness to oxidized lipoproteins [42]. Primarily, however, surface CD36 varies through currently unknown environmental cues, which now might include variation in the number of circulating exosomes. Since exosomes interfere with two essential elements of atherothrombosis, foam cell formation and platelet responsiveness to damaged arteries, these particles may confer, and predict, susceptibility to this disease process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The technical aid of R. Chen, N. Gupta, and M. Shivananjappa is greatly appreciated, as was preparation of NO2-LDL by Dr. D. Kennedy. We also appreciate the helpful assistance of S. O'Bryant of the LRI Flow Cytometry Core and particularly appreciate the aid of J. Drazba of the Imaging Core for TIRF microscopy. We also thank Dr. Drazba and along with M. Yin for transmission electron microscopy. We appreciate the aid of P. Narayanan with the Cellix flow system, and we thank our many blood donors. S.S. is a Ph.D. candidate at Case Western Reserve University and this work is submitted in partial fulfillment of the PhD requirement. This study was supported by research funding from the National Institutes of Health 1PO1 HL087018 to RLS and TMM, R01 HL111614 to RLS, and R01 AA017748 to TMM.

Abbreviations

- GP

glycoprotein

- K

lysine

- LDL

low density lipoprotein

- NO2-LDL

nitrated

- LDL, Ub

ubiquitin

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors report they have no real or potential conflicts of interest. All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

References

- 1.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:569–79. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heijnen HF, Schiel AE, Fijnheer R, Geuze HJ, Sixma JJ. Activated platelets release two types of membrane vesicles: microvesicles by surface shedding and exosomes derived from exocytosis of multivesicular bodies and alpha-granules. Blood. 1999;94:3791–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gambim MH, do Carmo Ade O, Marti L, Verissimo-Filho S, Lopes LR, Janiszewski M. Platelet-derived exosomes induce endothelial cell apoptosis through peroxynitrite generation: experimental evidence for a novel mechanism of septic vascular dysfunction. Crit Care. 2007;11:R107. doi: 10.1186/cc6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azevedo LC, Janiszewski M, Pontieri V, Pedro Mde A, Bassi E, Tucci PJ, Laurindo FR. Platelet-derived exosomes from septic shock patients induce myocardial dysfunction. Crit Care. 2007;11:R120. doi: 10.1186/cc6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh A, Li W, Febbraio M, Espinola RG, McCrae KR, Cockrell E, Silverstein RL. Platelet CD36 mediates interactions with endothelial cell-derived microparticles and contributes to thrombosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1934–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI34904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Febbraio M, Hajjar DP, Silverstein RL. CD36: a class B scavenger receptor involved in angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, inflammation, and lipid metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:785–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI14006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nergiz-Unal R, Rademakers T, Cosemans JM, Heemskerk JW. CD36 as a multiple-ligand signaling receptor in atherothrombosis. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2011;9:42–55. doi: 10.2174/187152511794182855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nergiz-Unal R, Lamers MM, Van Kruchten R, Luiken JJ, Cosemans JM, Glatz JF, Kuijpers MJ, Heemskerk JW. Signaling role of CD36 in platelet activation and thrombus formation on immobilized thrombospondin or oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1835–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abumrad NA, el-Maghrabi MR, Amri EZ, Lopez E, Grimaldi PA. Cloning of a rat adipocyte membrane protein implicated in binding or transport of long-chain fatty acids that is induced during preadipocyte differentiation. Homology with human CD36. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17665–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endemann G, Stanton LW, Madden KS, Bryant CM, White RT, Protter AA. CD36 is a receptor for oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11811–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahaman SO, Lennon DJ, Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Hazen SL, Silverstein RL. A CD36-dependent signaling cascade is necessary for macrophage foam cell formation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:211–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ren Y, Silverstein RL, Allen J, Savill J. CD36 gene transfer confers capacity for phagocytosis of cells undergoing apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1857–62. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asch AS, Barnwell J, Silverstein RL, Nachman RL. Isolation of the thrombospondin membrane receptor. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1054–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI112918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simantov R, Febbraio M, Silverstein RL. The antiangiogenic effect of thrombospondin-2 is mediated by CD36 and modulated by histidine-rich glycoprotein. Matrix Biol. 2005;24:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shantsila E, Kamphuisen PW, Lip GY. Circulating microparticles in cardiovascular disease: implications for atherogenesis and atherothrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2358–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Podrez EA, Poliakov E, Shen Z, Zhang R, Deng Y, Sun M, Finton PJ, Shan L, Gugiu B, Fox PL, Hoff HF, Salomon RG, Hazen SL. Identification of a novel family of oxidized phospholipids that serve as ligands for the macrophage scavenger receptor CD36. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38503–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Podrez EA, Byzova TV, Febbraio M, Salomon RG, Ma Y, Valiyaveettil M, Poliakov E, Sun M, Finton PJ, Curtis BR, Chen J, Zhang R, Silverstein RL, Hazen SL. Platelet CD36 links hyperlipidemia, oxidant stress and a prothrombotic phenotype. Nat Med. 2007;13:1086–95. doi: 10.1038/nm1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown GT, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide signaling without a nucleus: kinase cascades stimulate platelet shedding of proinflammatory IL-1beta-rich microparticles. J Immunol. 2011;186:5489–96. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caby MP, Lankar D, Vincendeau-Scherrer C, Raposo G, Bonnerot C. Exosomal-like vesicles are present in human blood plasma. Int Immunol. 2005;17:879–87. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, McIntyre TM, Silverstein RL. Ferric chloride-induced murine carotid arterial injury: A model of redoxpathology. Redox Biology. 2013;1:50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podrez EA, Schmitt D, Hoff HF, Hazen SL. Myeloperoxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species convert LDL into an atherogenic form in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1547–60. doi: 10.1172/JCI5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HS, Jeong J, Lee KJ. Characterization of vesicles secreted from insulinoma NIT-1 cells. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:2851–62. doi: 10.1021/pr900009y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buschow SI, Liefhebber JM, Wubbolts R, Stoorvogel W. Exosomes contain ubiquitinated proteins. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2005;35:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wegrzyn J, Lee J, Neveu JM, Lane WS, Hook V. Proteomics of neuroendocrine secretory vesicles reveal distinct functional systems for biosynthesis and exocytosis of peptide hormones and neurotransmitters. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:1652–65. doi: 10.1021/pr060503p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverstein RL, Febbraio M. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.272re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Endemann G, Stanton LW, Madden KS, Brant CM, White RT, Protter AA. CD36 is a receptor for oxidized low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11811–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinberg D. The LDL modification hypothesis of atherogenesis: an update. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S376–81. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800087-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hazen SL, Zhang R, Shen Z, Wu W, Podrez EA, MacPherson JC, Schmitt D, Mitra SN, Mukhopadhyay C, Chen Y, Cohen PA, Hoff HF, Abu-Soud HM. Formation of nitric oxide-derived oxidants by myeloperoxidase in monocytes: pathways for monocyte-mediated protein nitration and lipid peroxidation In vivo. Circ Res. 1999;85:950–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.10.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Podrez EA, Poliakov E, Shen Z, Zhang R, Deng Y, Sun M, Finton PJ, Shan L, Febbraio M, Hajjar DP, Silverstein RL, Hoff HF, Salomon RG, Hazen SL. A novel family of atherogenic oxidized phospholipids promotes macrophage foam cell formation via the scavenger receptor CD36 and is enriched in atherosclerotic lesions. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38517–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith J, Su X, El-Maghrabi R, Stahl PD, Abumrad NA. Opposite regulation of CD36 ubiquitination by fatty acids and insulin: effects on fatty acid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:13578–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee RD, Barcel DA, Williams JC, Wang JG, Boles JC, Manly DA, Key NS, Mackman N. Pre-analytical and analytical variables affecting the measurement of plasma-derived microparticle tissue factor activity. Thromb Res. 2012;129:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jayachandran M, Miller VM, Heit JA, Owen WG. Methodology for isolation, identification and characterization of microvesicles in peripheral blood. J Immunol Methods. 2012;375:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13368–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hochstrasser M. Protein degradation or regulation: Ub the judge. Cell. 1996;84:813–5. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pancre V, Pierce RJ, Fournier F, Mehtali M, Delanoye A, Capron A, Auriault C. Effect of ubiquitin on platelet functions: possible identity with platelet activity suppressive lymphokine (PASL) Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:2735–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830211113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ostrowska H, Ostrowska JK, Worowski K, Radziwon P. Human platelet 20S proteasome: inhibition of its chymotrypsin-like activity and identification of the proteasome activator PA28. A preliminary report. Platelets. 2003;14:151–7. doi: 10.1080/0953710031000092802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nayak MK, Kumar K, Dash D. Regulation of proteasome activity in activated human platelets. Cell Calcium. 2011;49:226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gupta N, Li W, Willard B, Silverstein RL, McIntyre TM. Proteasome proteolysis supports stimulated platelet function and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:160–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng W, Sun L, Jiang X, Chen X, Hou F, Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ. Reconstitution of the RIG-I pathway reveals a signaling role of unanchored polyubiquitin chains in innate immunity. Cell. 2010;141:315–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia ZP, Sun L, Chen X, Pineda G, Jiang X, Adhikari A, Zeng W, Chen ZJ. Direct activation of protein kinases by unanchored polyubiquitin chains. Nature. 2009;461:114–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kashiwagi H, Tomiyama Y, Nozaki S, Kiyoi T, Tadokoro S, Matsumoto K, Honda S, Kosugi S, Kurata Y, Matsuzawa Y. Analyses of genetic abnormalities in type I CD36 deficiency in Japan: identification and cell biological characterization of two novel mutations that cause CD36 deficiency in man. Hum Genet. 2001;108:459–66. doi: 10.1007/s004390100525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghosh A, Murugesan G, Chen K, Zhang L, Wang Q, Febbraio M, Anselmo RM, Marchant K, Barnard J, Silverstein RL. Platelet CD36 surface expression levels affect functional responses to oxidized LDL and are associated with inheritance of specific genetic polymorphisms. Blood. 2011;117:6355–66. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cserti-Gazdewich CM, Mayr WR, Dzik WH. Plasmodium falciparum malaria and the immunogenetics of ABO, HLA, and CD36 (platelet glycoprotein IV) Vox Sang. 2011;100:99–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westrick RJ, Winn ME. Eitzman DT. Murine models of vascular thrombosis (Eitzman series) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2079–93. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denis CV, Dubois C, Brass LF, Heemskerk JW, Lenting PJ. Biorheology Subcommittee of the SSCotI. Towards standardization of in vivo thrombosis studies in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9:1641–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rautou PE, Mackman N. Microvesicles as risk markers for venous thrombosis. Expert Rev Hematol. 2013;6:91–101. doi: 10.1586/ehm.12.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diaz-Ricart M, Tandon NN, Carretero M, Ordinas A, Bastida E, Jamieson GA. Platelets lacking functional CD36 (glycoprotein IV) show reduced adhesion to collagen in flowing whole blood. Blood. 1993;82:491–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuno K, Diaz-Ricart M, Montgomery RR, Aster RH, Jamieson GA, Tandon NN. Inhibition of platelet adhesion to collagen by monoclonal anti-CD36 antibodies. Br J Haematol. 1996;92:960–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.422962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alugupalli KR, Michelson AD, Barnard MR, Leong JM. Serial determinations of platelet counts in mice by flow cytometry. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:668–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.