Abstract

Recent studies report the Src-Family kinases(SFK’s) are important in a number of physiological and pathophysiological responses of pancreatic acinar cells(pancreatitis, growth, apoptosis), however, the role of SFKs in various signaling cascades important in mediating these cell functions is either not investigated or unclear. To address this we investigated the action of SFKs in these signaling cascades in rat pancreatic acini by modulating SFK activity using three methods:Adenovirus-induced expression of an inactive dominant-negative CSK(Dn-CSK-Advirus) or Wild-Type CSK(Wt-CSK-Advirus), which activate or inhibit SFK, respectively or using the chemical inhibitor, PP2, with its inactive control, PP3. CCK(0.3,100 nM) and TPA(1 µM) activated SFK and altered the activation of FAK proteins(PYK2, p125 FAK), adaptor proteins(p130CAS, paxillin), MAPK (p42/44, JNK, p38), Shc, PKC(PKD, MARCKS), Akt but not GSK3-β. Changes in SFK activity by using the three methods of altering SFK activity affected CCK/TPAs activation of SFK, PYK2, p125 FAK, p130CAS, Shc, paxillin, Akt but not p42/44, JNK, p38, PKC(PKD, MARCKS) or GSK3-β. With chemical inhibition the active SFK inhibitor, PP2, but not the inactive control analogue, PP3, showed these effects. For all stimulated changes pre-incubation with both adenoviruses showed similar effects to chemical inhibition of SFK activity. In conclusion, using three different approaches to altering Src activity allowed us to define fully for the first time the roles of SFKs in acinar cell signaling. Our results show that in pancreatic acinar cells, SFKs play a much wider role than previously reported in activating a number of important cellular signaling cascades shown to be important in mediating both acinar cell physiological and pathophysiological responses.

Keywords: Src, pancreatitis, pancreatic acini, CCK, signaling, focal adhesion kinases, MAP kinases

1. Introduction

The Src Family of Kinases (SFKs) plays a central signaling role in cells for growth factors, cytokines and G protein-coupled receptors (Aleshin and Finn, 2010). They are important in the signaling of many cellular processes such as cell secretion, endocytosis, growth, cytoskeletal integrity and apoptosis (Aleshin and Finn, 2010) which are mediated by these stimuli. Increasing evidence demonstrates that SFKs are important in pancreatic acinar cells, mediating normal cellular processes induced by growth factors and gastrointestinal hormones/neurotransmitters such as enzyme secretion, membrane recycling, endocytosis, protein synthesis, control of cellular calcium levels or regulation of PKCs (Liddle, 1994; Tsunoda et al, 1996; Tapia et al, 2003). Moreover, the SFKs are also involved in several pancreatic pathophysiological processes like inflammation, tumorigenesis and cell death regulation (Nagaraj et al, 2010; Ramnath et al, 2009). As a consequence of their participation in pancreatic acinar cells pathophysiological processes the SFK role in the development of acute pancreatitis and its role in the progression of pancreatic cancer have been extensively studied (Mishra et al, 2013). Because of the prominent role SFKs play in these inflammatory and neoplastic processes it has been proposed inhibition of SFK activity might be a useful therapeutic approach (George, Jr. et al, 2014).

A number of cellular signaling cascades have been identified which are important in mediating CCK’s physiological and pathophysiological effects. However, in most cases either the role of SFKs in these signaling cascades has not been studied or conflicting information exists whether Src-activation is important in their mediation. This has occurred, in part, because most of these studies used SFK inhibitors without the proper control compounds or used non-specific Src inhibitors, which in some cases could interact with other signaling kinases different than SFK (Bain et al, 2007; Blake et al, 2000). These latter points are important because detailed studies of SFK inhibitors have demonstrated that even the best are not absolutely specific; simultaneous assessment with the inactive analogue, PP3 in the case of the pyrazolo-pyrimidine inhibitors (PP1, PP2) allows increased specificity but it is frequently not used; and that even the recommendation of using more than one SFK inhibitor does not allow complete specificity (Bain et al, 2007). Specifically, herbimycin A, a commonly used SFK inhibitor, also used in some studies of pancreatic acinar cell function (Tsunoda et al, 1996), inhibits several tyrosine kinases, apart from Src (Murakami et al, 1998). The pyrazolo-pyrimidine compounds (PP1 and PP2), which have been widely used in a number of studies to evaluate the role of SFKs in cellular function (Bain et al, 2007), have been demonstrated to be able to inhibit other protein kinases (Bain et al, 2007) and thus an inactive control such as PP3 is essential to establish specificity. Even the indolinone analog SU6656, which was originally reported to be a more selective, potent inhibitor of SFKs (Blake et al, 2000), has subsequently been reported to interact with a number of other protein kinases (Bain et al, 2007). Almost all the information about the role of SFK in pancreatic acinar cells comes from studies using one of the SFK inhibitors alone, often without a control inactive variant and this may contribute to the conflicting results obtained in some cases (Ramnath et al, 2009; Nagaraj et al, 2010; Bain et al, 2007; Blake et al, 2000). Because of these possible limitations, it remains an open question as to which cellular signaling cascades the SFKs interact with in pancreatic acinar cells.

In the present study, we attempted to address this question by using three different approaches to alter SFK activity in pancreatic acinar cells. First, we inhibited SFK activity by inducing the expression of Wild-Type CSK (Wt-CSK-Advirus), which specifically inhibits SFK (Okada, 2012). Second, we performed the reverse experiment to activate SFKs by inducing the expression of an inactive dominant-negative version of CSK through an adenovirus infection (Dn-CSK-Advirus) (Adam et al, 2010), which results in SFK activation. Lastly, we inhibited SFK activity by a different mechanism using the general SFK antagonist PP2, with the inactive chemically related analogue PP3 as a control under identical conditions. Using these three methods of modulation of SFK activity we studied the activation of several cellular signaling cascades reported to be important in mediating the physiological and pathophysiological processes cell growth, differentiation, adhesion, secretion, in mediating pancreatitis and cell death regulation activated by CCK in the pancreatic acini (Piiper et al, 2003; Ferris et al, 1999; Tapia et al, 1999; Pace et al, 2003; Berna et al, 2007; Pace et al, 2006; Garcia et al, 1997; Sancho et al, 2012).

To perform these studies we assessed the effects of SFK modulation on both basal SFK activity, as well as the effect on stimulated SFK activity by the hormone/neurotransmitter, cholecystokinin (CCK). CCK is a physiological regulator of pancreatic acinar cell function (Tapia et al, 1999; Sancho et al, 2012) and is reported to activate SFKs in pancreatic acinar cells (Piiper et al, 2003; Ferris et al, 1999; Tapia et al, 1999; Pace et al, 2003; Berna et al, 2007; Pace et al, 2006; Garcia et al, 1997; Sancho et al, 2012). Because CCK is reported to have both physiological effects (Tapia et al, 1999; Pace et al, 2003), as well as pathophysiological effects, at supramaximal concentrations (causing pancreatitis-like changes) (Yuan et al, 2012), in our studies we used a physiological equivalent in vitro (0.3 nM) concentration of CCK and also a pathophysiological (100 nM) CCK concentration. The 100 nM high dose CCK was used because previous studies reported it induces maximal activation of the SFK members Yes and Lyn in pancreas (Sancho et al, 2012; Pace et al, 2006), it activates both high- and low-affinity CCK receptors (Pace et al, 2003; Sancho et al, 2012; Pace et al, 2006) and causes pathophysiological changes. The 0.3 nM CCK dose was used because it results in only high affinity receptor activation as seen in physiological activation and is the minimal CCK dose that can reproducibly stimulate many of the cellular cascades measured. We also used the phorbol ester, TPA, which directly activates PKCs and therefore mimics one of the main cellular signaling cascades of a number of physiological stimulants of acinar cells (CCK, acetylcholine, gastrin-releasing peptide, substance P) (Sancho et al, 2012; Pace et al, 2006).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (150–250 g) were obtained from the Small Animals Section, Veterinary Resources Branch, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD. Rabbit anti-phospho-Src family (Tyr416), rabbit anti-Src family, rabbit anti-phospho-PYK2 (Tyr 402), rabbit anti PYK2, rabbit anti-phospho- p125FAK (Tyr397), rabbit anti p125FAK, rabbit anti-phospho-p130Cas (Tyr 410), rabbit anti-phospho-paxillin (Tyr 118), rabbit anti-paxillin, rabbit anti-phospho-Shc (Tyr 239/240), rabbit anti-Shc, rabbit anti-phospho-p42/44 mitogen-activated-protein-kinase (MAPK) (Tyr 202/204), rabbit anti-p42/44 mitogen-activated-protein-kinase (MAPK), rabbit anti-phospho-p38 (Tyr 180/182), rabbit anti-p38, rabbit anti-phospho-Jnk (Thr 183/ Tyr 185), rabbit anti-Jnk, rabbit anti-phospho-GSK-3-β (Ser 9), rabbit anti-GSK-3-β, rabbit anti-phospho-PKD (Ser744/748), rabbit anti-PKD, rabbit anti-phospho-Marcks (Ser 152/156), rabbit anti-Csk, rabbit anti-α/β tubulin antibodies and nonfat dry milk were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc (Beverly, MA). Rabbit anti-p130CAS and anti-rabbit-HRP-conjugate antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Tris/HCl pH 8.0 and 7.5 were from Mediatech, Inc. (Herndon, VA). 2-mercaptoethanol, protein assay solution, sodium lauryl sulfate (SDS) and Tris/Glycine/SDS (10X) were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). MgCl2, CaCl2, Tris/HCl 1M pH 7.5 and Tris/Glycine buffer (10x) were from Quality Biological, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). Minimal essential media (MEM) vitamin solution, amino acids 100x, Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS), glutamine (200 mM), Tris-Glycine gels, L-glutamine, Waymouth´s MB 752/1 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). COOH-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin (CCK) was from Bachem Bioscience Inc. (King of Prussia, PA). PP2 and PP3 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Carbachol, insulin, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 12-O-tetradecanoylphobol-13-acetate (TPA), L-glutamic acid, glucose, fumaric acid, pyruvic acid, trypsin inhibitor, HEPES, TWEEN® 20, Triton X-100, phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), sucrose, sodium-orthovanadate and sodium azide were from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St. Louis, MO). Albumin standard and Super Signal West (Pico, Dura) chemiluminescent substrate were from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Protease inhibitor tablets were from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Purified collagenase (type CLSPA) was from Worthington Biochemicals (Freehold, NJ). Nitrocellulose membranes were from Schleicher and Schuell Bioscience, Inc. (Keene, NH). Biocoat collagen I Cellware 60 mm dishes were from Becton Dickinsen Labware (Bedford, MA). Albumin bovine fraction V was from MP Biomedical (Solon, OH). NaCl, KCl and NaH2PO4 were from Mallinckrodt (Paris, KY). Ad-CMV-Null adenovirus was from Q-Biogene (Carlsbad, CA). Dominant negative CSK Recombinant Adenovirus, Wild type CSK Recombinant Adenovirus, QuickTiter™ Adenovirus Quantitation Kit and ViraBind™ Adenovirus Purification Kit were from Cell Biolabs, Inc. (San Diego, CA).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Tissue Preparation

Animals were housed, cared for and treated according to an approved protocol following the guidelines of the NIH Animal Use Committee. Pancreatic acini were obtained by collagenase digestion as previously described (Tapia et al, 1999; Sancho et al, 2012). Standard incubation solution contained 25.5 mM HEPES (pH 7.45), 98 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 2.5 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM sodium pyruvate, 5 mM sodium glutamate, 5 mM sodium fumarate, 11.5 mM glucose, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM glutamine, 1% (w/v) albumin, 0.01% (w/v) trypsin inhibitor, 1% (v/v) vitamin mixture and 1% (v/v) amino acid mixture.

2.2.2. Acini Stimulation

After collagenase digestion, dispersed acini were pre-incubated in standard incubation solution for 2 hrs at 37 °C with or without inhibitors as described previously (Tapia et al, 1999; Pace et al, 2003). After pre-incubation 1 ml aliquots of dispersed acini were incubated at 37 °C with or without stimulants. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium azide, 1 mM EGTA, 0.4 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM PMSF, and one protease inhibitor tablet per 10 ml). After sonication, lysates were centrifuged at 10,000x g for 15 min at 4 °C and protein concentration was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent.

2.2.3. Virus infection in cultured acini

Pancreatic acini were isolated as described above, infected with either Ad-CMV-Null (empty adenovirus, as infection control), dominant negative CSK adenovirus or Wild Type CSK adenovirus at 1 × 109 VP/ml concentration, as described previously (Berna et al, 2007). After 6 h, stimulants were added and cells lysed as described above.

2.2.4. Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously (Garcia et al, 1997). Briefly, equal amounts of protein from whole cell lysates were loaded on to SDS-PAGE using 4–20% Tris-Glycine gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Ca). After electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 2 hours for detection of signaling cascades levels. After the transfer membranes were washed twice in washing buffer (TBS plus 0.1% Tween®20), at room temperature for 1 h, and then incubated with primary antibody at 1:1000 dilution in washing buffer + 5% BSA overnight at 4°C, under constant agitation. After primary antibody incubation, membranes were washed twice in blocking buffer (TBS, 0.1% Tween® 20, 5% non-fat dry milk) for 4 min and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (α-rabbit) for 1 h at room temperature under constant agitation. Membranes were washed again twice in blocking buffer for 4 min, and then twice in washing buffer for 4 min. Then, the membranes were incubated with chemiluminescence detection reagents for 4 min and finally were exposed to Kodak Biomax film (MR, MS). Tubulin and total Src-antibodies were used to assess equal loading on these experiments. When re-probing was necessary membranes were incubated in Stripping buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed twice for 10 min in washing buffer, blocked for 1 hour in blocking buffer at room temperature and re-probed.

2.2.5. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least 3 times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and were analyzed using the one-way ANOVA analysis with Dunnett´s or Bonferroni multiple test as post hoc tests using the GraphPad 5.0 software. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. CCK and TPA induce activation of several kinases in pancreatic acinar cells

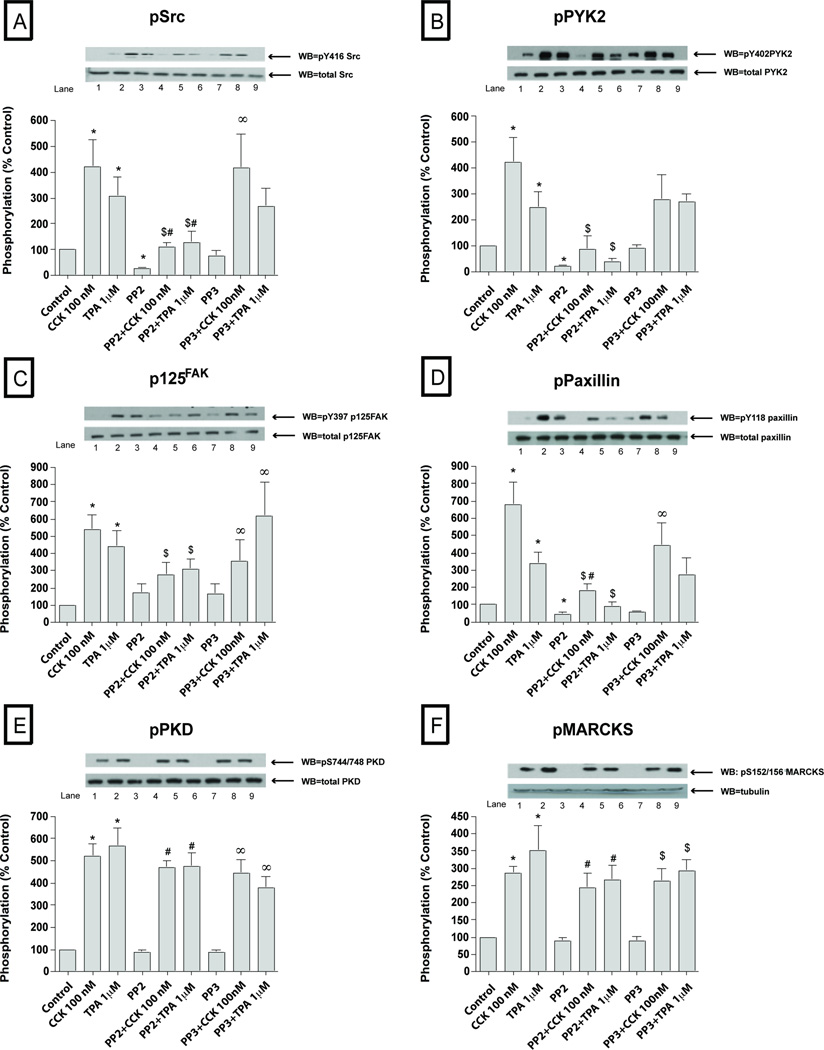

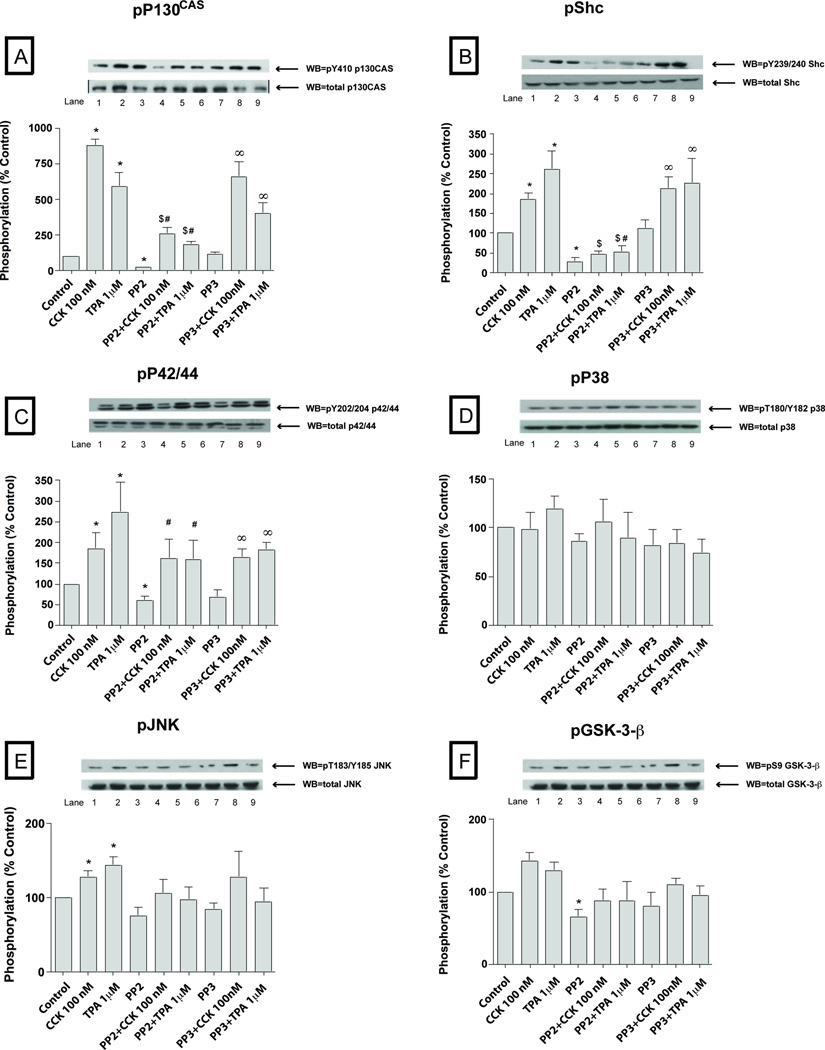

To explore the possible importance of SFK activation by CCK in pancreatic acini, we first examined CCKs ability to activate various cell signaling cascades reported to be important for mediating its various cellular responses such as secretion, proliferation and cytokine release. To accomplish this, we assessed the effect of CCK at physiological (0.3 nM) and supraphysiological (100 nM) concentrations, as well as the effect of the PKC activator, TPA, to activate SFKs. We also analyzed the activation of a number of cellular signalling cascades reported to be important in mediating CCK’s physiological or pathophysiological effects in the above acinar responses. The supra-physiological 100 nM concentration of CCK (Fig. 1–2; Table 1) induced activation of Src (420±107% Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 1A) and several other kinases including PYK2 (425±96%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 1B), p125FAK (539±85%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 1C), paxillin (678 ±130%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 1D), PKD (519±56%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 1E), MARCKS (285±21%Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 1F), p130Cas (878±46%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 2A), Shc (184±18%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2B) and, to a lesser extent, the MAPKS p42/44 (165±34%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2C) and JNK (145±9%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2E). P38 was activated, but just in the cells preincubated during 6 hours for the virus infection (134±9%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2D and Fig. 7D). GSK3-β (Fig. 2F) was not significantly increased by 100 nM CCK.

Fig. 1. Effect of PP2 and PP3 on the ability of TPA or a supraphysiological concentration of CCK (100 nM) to stimulate various kinases (Src, PYK2, p125FAK, paxillin, PKD and MARCKs).

Rat pancreatic acinar cells were pretreated with no additions or with PP2 (10 µM) or PP3 (10 µM) for 1 h and then incubated with no additions (control), with 100 nM CCK for 2.5 min or with 1 µM TPA for 5 min and then lysed. Whole cell lysates were submitted to SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were analyzed using anti-pY416 Src, pY402 PYK2, pY397 p125FAK, pY118 paxillin, pY744/748 PKD and pSer156 MARCKS. Antibodies detecting total amount of these kinases were used to verify loading of equal amounts of protein. The bands were visualized using chemoluminescence and quantification of phosphorylation was assessed using scanning densitometry. Both a representative experiment of 3 others and the means of all the experiments are shown. * P< 0.05 vs control, # P< 0.05 vs PP2 alone, ∞ P< 0.05 vs PP3 alone and $ P< 0.05 comparing stimulants (CCK or TPA) vs stimulants pre-incubated with PP2 or PP3, respectively.

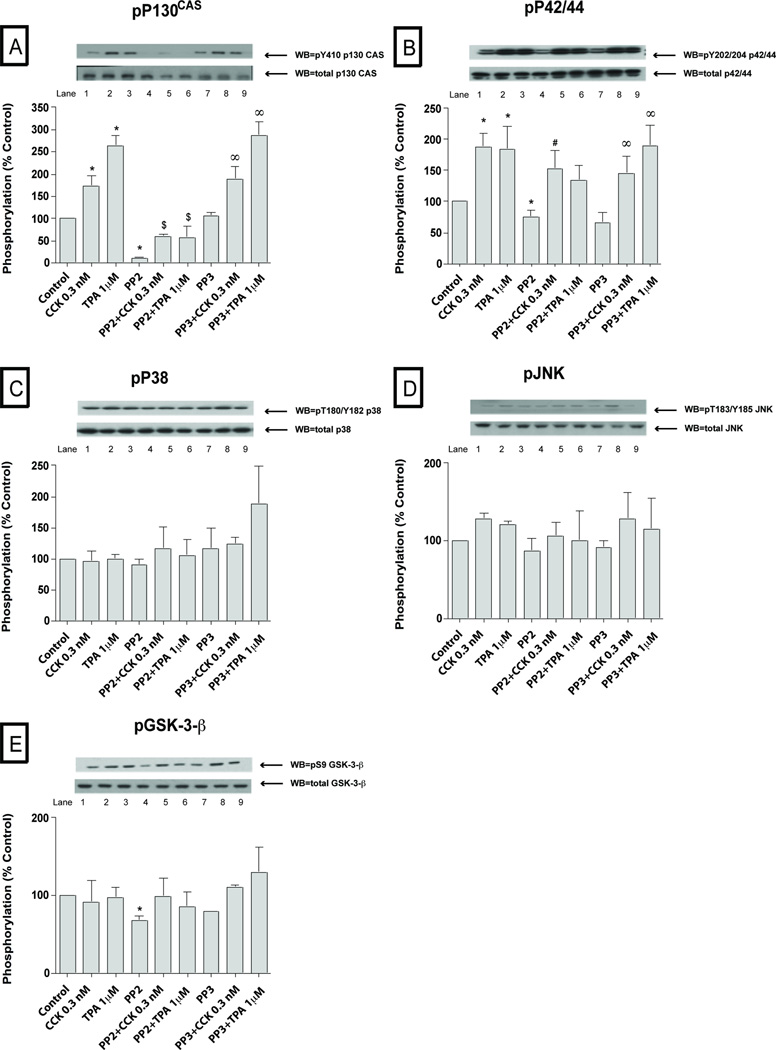

Fig. 2. Effect of PP2 and PP3 on the ability of TPA or a supraphysiological concentration of CCK (100 nM) to stimulate various kinases (p130CAS, Shc, p42/44, p38, JNK and GSK3-β.

Rat pancreatic acinar cells and the whole cell lysates were processed as outlined in Figure 1 legend. Membranes were analyzed using anti-pY410 p130CAS, pY239/240 Shc, pY202/204 p42/44, pThr180/Y182 p38, pYThr183/Y185 JNK and pSer9 GSK3-β. Both a representative experiment of 3 others and the means of all the experiments are shown. * P< 0.05 vs control, # P< 0.05 vs PP2 alone, ∞ P< 0.05 vs PP3 alone and $ P< 0.05 comparing stimulants (CCK or TPA) vs stimulants pre-incubated with PP2 or PP3, respectively.

Table 1.

Effects of CCK or TPA stimulation in rat pancreatic acini, with or without modulation of the activation of SFK (a).

| Stimulation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Yes | No |

| I. Kinase stimulation | ||

| By 100 nM CCK (b) | Src, PYK2, p125FAK, Paxillin, PKD, MARCKS, p130CAS, Shc, p42/44, JNK, p38 and Akt (inhibited). |

GSK3-β. |

| By 0.3 nM CCK (c) | Src, PYK2, p125FAK, Paxillin, PKD, p42/44. | p130CAS, Shc, p38, JNK, GSK3-β, MARCKS. |

| By 1 µM TPA (b, c) | Src, PYK2, p125FAK, paxillin, PKD, MARCKS, p130CAS, Shc, p42/44, JNK and Akt (inhibited). |

p38, GSK3-β. |

| II. Kinase inhibition by 10 µM PP2 | ||

| Of basal (b, c) | Src, PYK2, Paxillin, p130CAS, Shc, p42/44, GSK3-β, Akt. |

p125FAK, PKD, MARCKS, p38, JNK. |

| Of 100 nM CCK kinases stimulation (b) | Src, PYK2, p125FAK, Paxillin, p130CAS, Shc. | PKD, MARCKS, p42/44, p38, JNK, GSK3-β, Akt. |

| Of 0.3 nM CCK stimulation (c) | Src, PYK2, Paxillin. | p125FAK, PKD, p130CAS, Shc, p42/44, p38, JNK, GSK3-β, MARCKS. |

| Of 1 µM TPA stimulation (b, c) | Src, PYK2, p125FAK, Paxillin, p130CAS, Shc. | PKD, p42/44, p38, JNK, GSK3-β, MARCKS, Akt. |

|

III. DN-CSK-Advirus kinase Basal stimulation (d) |

Src, PYK2, p125FAK, Paxillin, p130CAS, Shc. | PKD, p42/44, p38, JNK, GSK3-β. |

|

IV. WT-CSK-Advirus kinase Basal stimulation (d) |

Src, PYK2, p125FAK, Paxillin, p130CAS, Shc | PKD, p42/44, p38, JNK, GSK3-β. |

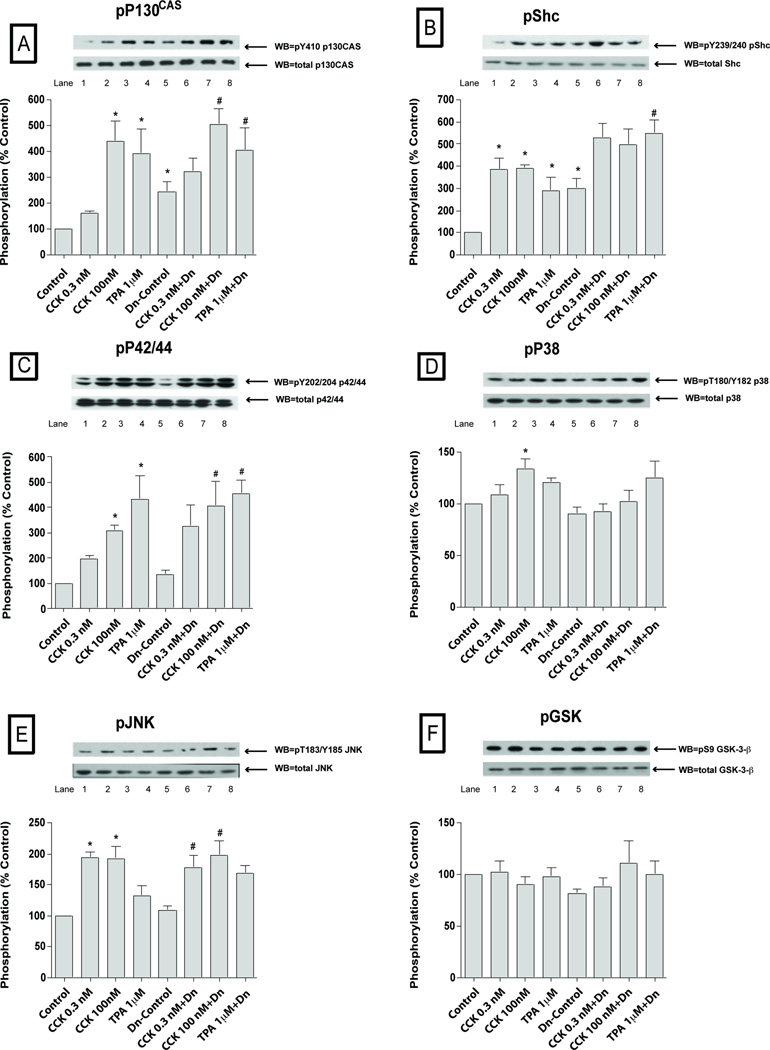

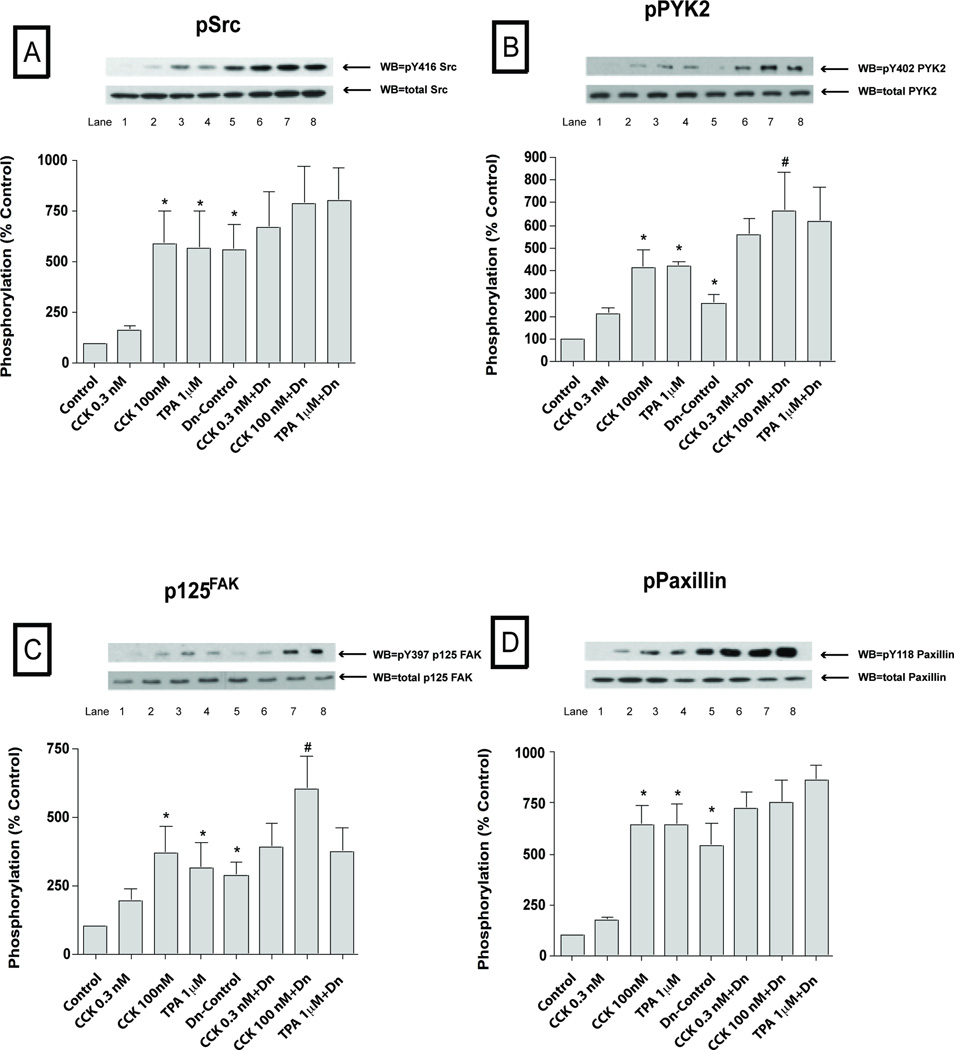

Fig. 7. Effect of pre-incubation with the SFK stimulating CSK dominant negative virus (DN-CSK-Advirus) on basal, CCK- and TPA-stimulated phosphorylation of kinases (p130CAS, Shc, p42/44, p38, JNK and GSK3-β).

Effect of stimulation by CCK and TPA stimulation on the phosphorylation of p130CAS, Shc, P42/44, P38, JNK and GSK3-β in rat pancreatic acinar cells pre-incubated with 109 VP/ml of a nulled-Advirus or DN-CSK-Advirus (10 µM) for 6 h, which results in SFK activation. Subsequently, acini were incubated with no additions (control), with 0.3 nM CCK, 100 nM CCK for 2.5 min or with 1µM TPA for 5 min and then lysed. Whole cell lysates and membranes were processed as indicated in Figure 1-legend. Membranes were analyzed using anti-pY410 p130CAS, pY239/240 Shc, pY202/204 p42/44, pThr180/Y182 p38, pYThr183/Y185 JNK and pSer9 GSK3-β. Both a representative experiment of 3 others and the means of all the experiments are shown. * P< 0.05 vs control, # P< 0.05 vs DN-CSK-Ad-virus-control.

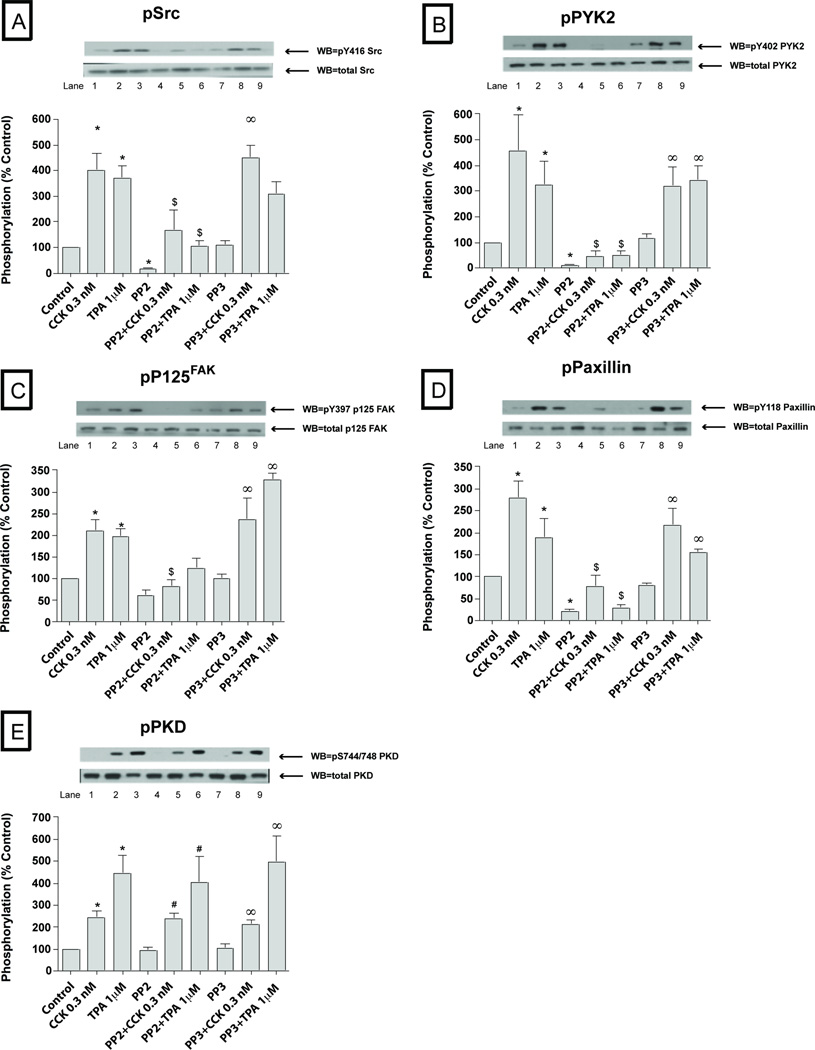

At a physiological CCK concentration (0.3 nM), in addition to stimulating SFK activation, PYK2, P125 FAK, paxillin, p130Cas, PKD and p42/44 also were activated (Fig. 3–4, Table 1). The magnitude of the activation of Src (401±59% Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 3A), PYK2 (457±140% Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 3B) and p42/44 (188±36% Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 4B) with 0.3 nM CCK was similar to that seen with the 100 nM CCK concentration. In contrast, the magnitude of the activation of p125FAK (211±25% Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 3C), paxillin (280±38% Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 3D), p130Cas (172±25 Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 4A), PKD (242±30% Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 3E) were significantly lower (p<0.05) than seen with the 100 nM CCK concentration. Similarly to the 100 nM CCK concentration, p38 (Fig. 4C) and GSK3-β (Fig. 4E) were not responsive to CCK at this physiological concentration. Furthermore, we did not detect any signal of activation of Shc, JNK or MARCKS at this concentration of 0.3 nM CCK; whereas each was activated at the 100 nM CCK concentration (Fig. 1–2; Fig. 4D, Table 1).

Fig. 3. Effect of PP2 and PP3 on the ability of TPA or a physiological concentration of CCK (0.3 nM) to stimulate various kinases (Src, PYK2, p125FAK, paxillin and PKD).

Rat pancreatic acinar cells were pretreated with no additions or with PP2 (10 µM) or PP3 (10 µM) for 1 h and then incubated with 0.3 nM CCK or TPA (1 µM). The whole cell lysates were processed as described in the Figure 1 legend. Membranes were analyzed using anti-pY416 Src, pY402 PYK2, pY397 p125FAK, pY118 paxillin and pY744/748 PKD. Both a representative experiment of 3 others and the means of all the experiments are shown. * P< 0.05 vs control, # P< 0.05 vs PP2 alone, ∞ P< 0.05 vs PP3 alone and $ P< 0.05 comparing stimulants (CCK or TPA) vs stimulants pre-incubated with PP2 or PP3, respectively.

Fig. 4. Effect of PP2 and PP3 on the ability of TPA or a physiological concentration of CCK (0.3 nM) to stimulate various kinases (p130CAS, Shc, p42/44, p38, JNK and GSK3-β).

Rat pancreatic acinar cells were treated as indicated in the Figure 3 legend. Membranes were analyzed using anti-pY410 p130CAS, pY202/204 p42/44, pThr180/Y182 p38, pYThr183/Y185 JNK and pSer9 GSK3-β. Both a representative experiment of 3 others and the means of all the experiments are shown. * P< 0.05 vs control, # P< 0.05 vs PP2 alone, ∞ P< 0.05 vs PP3 alone and $ P< 0.05 comparing stimulants (CCK or TPA) vs stimulants pre-incubate with PP2 or PP3, respectively.

The PKC activating agent, TPA (Fig. 1–4; Table 1) stimulated phosphorylation of all the kinases with the exception of p38 (Fig. 2D, 4C; Table 1) and GSK3-β (Fig. 2F, 4E). Specifically, after 5 minutes of incubation with 1 µM TPA, Src (337±41% Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 1A, 3A), PYK2 (288±48%Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 1B, 3B), p125FAK (317±59%Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 1C, 3C), paxillin (262±43%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 1D, 3D), PKD (512±56%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 1E, 3E), MARCKS (350±73%Δ of basal, p<0.01) (Fig. 1F), p130Cas (377±88%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 2A, 4A), Shc (262±45%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2B), p42/44 (210±37%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2C, 4B) and, to a lower extent, JNK (144±11%Δ of basal, p<0.05) were all activated by TPA (Fig. 2E, 4D).

3.2. Basal activation of several kinases is reduced by the specific Src inhibitor PP2 but not by PP3 in pancreatic acinar cells

Basal Src kinase activity (Fig. 1–4; Table 1) was significantly reduced after 1 hour pre-incubation with 10 µM PP2 (−80±4%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 1A, 3A), whereas, it was unaffected by 10 µM PP3. Basal phosphorylation of PYK2 (−84±4%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 1B, 3B), paxillin (−69±8%Δ of basal, p<0.001) (Fig. 1D, 3D), p130Cas (−82±3%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2A, 4A), Shc (−72±10%Δ of basal, p<0.005) (Fig. 2B), p42/44 (−33±7%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2C, 4B), GSK3-β (−34±6%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (Fig. 2F, 4E) and AKT (−64±14%Δ of basal, p<0.05) (data not shown) were decreased in the PP2-treated cells compared to controls. Pre-incubation with 10 µM PP3 did not have any effect in reducing the basal phosphorylation of any of these kinases.

3.3. CCK-and TPA-induced activation of several kinases is inhibited by PP2, but not PP3, in pancreatic acinar cells

We first established whether the concentrations of PP2 used resulted in >90% inhibition of CCK- (0.3 nM; 100 nM) and TPA-stimulated SFK activation under the experimental conditions used. Whereas, the control analogue, PP3 was inactive, PP2 (10 µM) inhibited by >90% CCK (0.3 nM; 100 nM) stimulation of SFK as well as that by TPA (Fig. 1–4; Table 1). In the PP2-treated cells, the supra-physiological (Fig. 1–2; Table 1) 100 nM CCK induced phosphorylation of a number of proteins was significantly reduced after 1 h pre-incubation with 10 µM PP2, however PP3 had no effect. This includes the stimulation of phosphorylation of PYK2 (21±9% of CCK alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 1B), p125FAK (48±8% of CCK alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 1C), paxillin (30±8% of CCK alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 1D), p130Cas (30±5% of CCK alone, p<0.001) (Fig. 2A) and Shc (25±4% of CCK alone, p<0.01) (Fig. 2B). In contrast, pre-incubation with PP2 (10 µM) did not affect the CCK (100 nM) stimulation of the phosphorylation of p42/44 (Fig. 2C), PKD (Fig. 2E) or MARCKS (Fig. 2F). There was a trend towards a decrease (20%) by PP2 in CCK-stimulated JNK (Fig. 2E), however it did not reach statistical significance.

On the other hand (Fig. 3–4; Table 1), stimulation by the physiological 0.3 nM CCK was significantly reduced by 10 µM PP2 for PYK2 (12±5% of CCK alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 3B), paxillin (27±7% of CCK alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 3D), p125FAK (41±4% of CCK alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 3C) and p130Cas (38±8% of CCK alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 4A), and in each case PP3 was without effect. Moreover, pre-incubation with PP2 (10 µM) reduced the TPA 1 µM stimulation of Src (34±4% of TPA alone, p<0.001) (Fig. 1A, 3A), PYK2 (19±6% of TPA alone, p<0.001) (Fig. 1B, 3B), p125FAK (69±9% of TPA alone, p<0.05) (Fig. 1C, 3C), paxillin (22±6% of CCK alone, p<0.01) (Fig. 1D, 3D), p130Cas (28±7% of TPA alone, p<0.01) (Fig. 2A, 4A) and Shc (22±8% of TPA alone, p<0.01) (Fig. 2B). In each case, TPA stimulation was not affected by the control analogue PP3. As reported previously (Berna et al, 2009) CCK and TPA reduced Akt, and the addition of PP2 had no effect on this (data not shown).

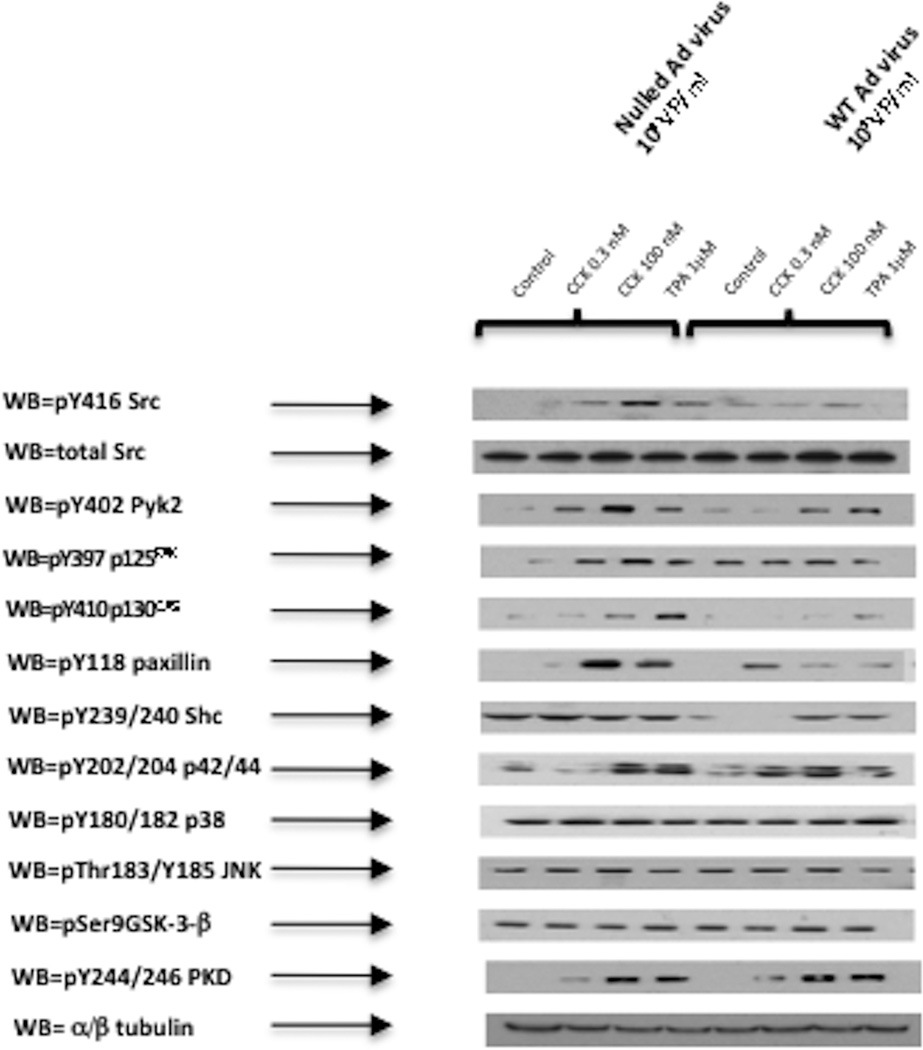

3.4. Effects of Src activity modulation, by pre-incubation with a Dn-CSK-Advirus or a WT-CSK-Advirus, upon the phosphorylation of several kinases

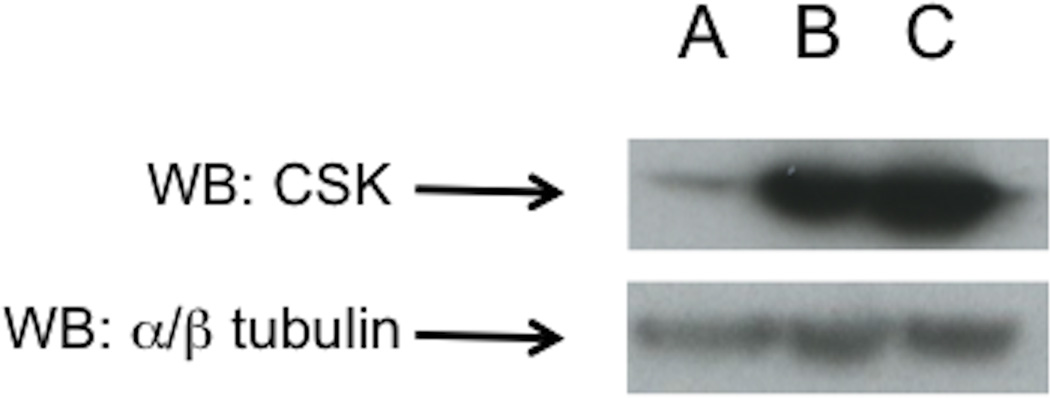

In order to corroborate the results obtained with chemical inhibition with PP2 pre-incubation, we used two other approaches to assess the importance of SFK in the cellular signaling cascades by modulating Src activity using two different adenoviruses (Dn-CSK-Advirus and Wt-CSK-Advirus). Dn-CSK-Advirus, modulates Src activity by inducing expression of a dominant-negative version of CSK (Dn-CSK-Advirus), which results in Src activation (Adam et al, 2010). On the other hand, the expression of the wild-Type CSK, by infection with the Wt-CSK-Ad-virus, inhibits Src activity (Okada, 2012). The incubation with both WT-and DN-CSK adenovirus resulted in the over-expression of the active and inactive version of CSK (Fig. 5). Once the effectiveness of the virus infection was confirmed new cells were infected with the viruses followed by stimulation with CCK (0.3 or 100 nM) or TPA 1 µM as performed in the PP2/PP3 experiments described above.

Fig. 5. Effect of pre-incubation with CSK-AD viruses upon the expression of CSK in pancreatic acinar cells.

Rat pancreatic acinar cells were pre-incubated for 6 h with 109 VP/ml of a control, nulled adenovirus (row A), a WT-CSK-Advirus expressing a wild type version of CSK (row B) which results in SFK inhibition or a DN-Csk-Advirus (row C), that express an inactive version of CSK resulting in SFK activation. This experiment is representative of 3 others.

In the control cells, (Fig. 6–7; Table 1) after pre-incubation for six hours with the inactive control null-Ad-virus, CCK 0.3 nM did not activate significantly any of the kinases, with the exception of Shc (386±59%Δ of control, p<0.01) (Fig. 7B), and JNK (194 ±9%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7E). However, with the 100 nM CCK concentration a clear activation was seen with Src (585±164%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6A), PYK2 (415±78%Δ of control, p<0.01) (Fig. 6B), p125FAK (372±94%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6C), paxillin (642±95%Δ of control, p<0.01) (Fig. 6D), p130Cas (442±75%Δ of control, p<0.01) (Fig. 7A), Shc (391±20%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7B), p42/44 (310±19%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7C) and, to a lesser extent, p38 (134±9%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7D). Similarly, TPA 1 µM also stimulated Src (568±180%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6A), PYK2 (421±19%Δ of control, p<0.01) (Fig. 6B), p125FAK (317±92%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6C), paxillin (641±103%Δ of control, p<0.01) (Fig. 6D), p130Cas (390±97%Δ of control, p<0.01) (Fig. 7A), Shc (290±70%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7B) and p42/44 (431±96%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7C).

Fig. 6. Effect of pre-incubation with the SFK stimulating CSK dominant negative virus (DN-CSK-Advirus) on basal, CCK- and TPA-stimulated phosphorylation of kinases (Src, PYK2, p125FAK, paxillin).

Rat pancreatic acinar cells were pre-incubated with 109 VP/ml of a control, nulled adenovirus or DN-Csk-Advirus for 6 h, which results in SFK activation. Subsequently, cell were incubated with no additions (control), with 0.3 nM CCK, 100 nM CCK for 2.5 min or with 1 µM TPA for 5 min and then lysed. Whole cell lysates and membranes were processed as indicated in Figure 1-legend. Membranes were analyzed using anti-pY416 Src, pY402 PYK2, pY397 p125FAK, and pY118 paxillin. Both a representative experiment of 3 others and the means of all the experiments are shown.* P< 0.05 vs control, # P< 0.05 vs DN-CSK-Ad-virus-control.

In the pancreatic acinar cells after pre-incubation during 6 hours with the SFK activating dominant-negative CSK adenovirus (Dn-CSK-Advirus), there was an increment in the basal phosphorylation of Src (560±125%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6A), PYK2 (256 ±39%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6B), p125FAK (288±49%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6C), paxillin (538±116%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6D), p130Cas (242±40%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7A), and Shc (301±54%Δ of control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7B).

Despite the higher basal levels of activation in the Dn-CSK-Advirus incubated cells, the supra-physiological concentration of CCK (100 nM) stimulated additional activation of PYK2 (289±98%Δ of DN-control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6B), p125FAK (227±50%Δ of DN-control, p<0.05) (Fig. 6C) and p130Cas (214±12%Δ of DN-control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7A). CCK 0.3 nM did not further increase the phosphorylation of kinases in Dn-CSK-Advirus incubated cells. TPA 1 µM increased p130Cas (163±10%Δ of DN-control, p<0.01) (Fig. 7A) and Shc (193±38%Δ of DN-control, p<0.05) (Fig. 7B). However, due to the high basal level of activation of these kinases we could not determine the proportion of increment in activation observed in the CCK-treated-DN-CSK-Ad virus infected cells which was due to CCK itself or for the constitutively activation of SFK.

The inhibition of Src by Wt-CSK-Advirus pre-incubation had a generally similar effect to that of the PP2 inhibition (Fig. 8, Table 1). Specifically, it resulted in basal inhibition of p130CAS, and Shc. The Wt-CSK-Advirus inhibited the stimulation by 0.3 nM CCK of the phosphorylation of PYK2, 125FAK, p130Cas, paxillin, and Shc (Fig. 8, Table 1). Moreover, the 100 nM CCK stimulation of PYK2, p125FAK, p130CAS, paxillin, Shc and Src were all inhibited after pre-incubation with the Wt-CSK-Advirus. Also, the TPA stimulation of p125FAK, p130CAS, paxillin and Src were inhibited when cells were infected with Wt-CSK-Advirus (Fig. 8, Table 1).

Fig. 8. Effect of pre-incubation with SFK inhibiting CSK wild type virus (WT-CSK-Advirus) on basal, CCK- and TPA-stimulated phosphorylation of various kinases.

Effect of stimulation by CCK and TPA on the phosphorylation of PYK2, p125FAK, p130CAS, Paxillin, Shc, P42/44, P38, JNK, GSK3-β, Src and PKD in rat pancreatic acinar cells pre-incubated with 109 VP/ml of a control (Nulled-Advirus) or WT-CSK-Advirus (10 µM) for 6 h. Subsequently, acini were incubated with no additions (control), with 0.3 nM CCK, 100 nM CCK for 2.5 min or with 1 µM TPA for 5 min and then lysed. Whole cell lysates and membranes were processed as indicated in Figure 1-legend. Membranes were analyzed using, pY402 PYK2, pY397 p125FAK, anti-pY410 p130CAS, pY118 paxillin, pY239/240 Shc, pY202/204 p42/44, pThr180/Y182 p38, pYThr183/Y185 JNK, pSer9 GSK3-β, anti-pY416 Src and pY744/748 PKD. These results are representative of 3 experiments.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to fully characterize the role of SFK in affecting signal cascades known to be important in mediating physiological or pathophysiological responses in pancreatic acinar cells. In contrast to previous studies that have explored SFK activation in pancreatic acinar cells, in this study we altered SFK activity by a number of different approaches, which allowed us to firmly establish which cellular signaling cascades SFK was involved in but avoid non-specific effects. Our study was performed by preincubation with two different adenoviruses expressing an active or a dominant negative form of CSK, a well-known down-regulator of SFK, resulting in either over-activation or inactivation of SFKs, respectively and also by using the chemical inhibitor PP2, with its inactive control PP3(Tsunoda et al, 1996; Tapia et al, 2003; Pace et al, 2006; Nagaraj et al, 2010; Bhatia, 2004). Overall, the results obtained by the three methods of modulation of SFK activity gave similar results. However, we observed some differences with the physiological concentration of CCK (CCK 0.3 nM) to activate some signaling kinases in the control-nulled adenovirus as compared to PP2-treated cells. This was most likely due to the fact that the virus treated cells required a 6 hour preincubation with the virus and were in general slightly less responsive to stimulation. However, we were able to confirm all our results with the chemical inhibition by performing the reverse study to over-activate SFKs using preincubated with the DN-CSK-Ad-virus, since the effect of the CCK 0.3 nM upon the activation of many of these kinases was enhanced with this approach. Our results can best be seen by discussing them in light of SFKs effect on four important signaling cascades in pancreatic acinar cells which have been shown to be important in mediating many of the acinar cell responses to stimuli. These include the activation of the focal adhesion kinase pathway, the mitogen-activated kinases (MAPKs) pathway, the PI3K/Akt/ GSK-3β pathway and the PKC pathway.

The focal adhesion kinases (FAKs), p125FAK and PYK2 have a Src-interacting domain and in a number of cell systems, SFK’s interaction with FAK can result in the activation of either FAK or Src (Antonieta Cote-Velez et al, 2001). Previous studies demonstrate CCK can activate both p125FAK and PYK2 in pancreatic acinar cells (Garcia et al, 1997; Tapia et al, 1999). Our results demonstrate that SFK activation induced by CCK, at both physiological and supra-physiological concentrations, or by the direct PKC activator, TPA, precedes and is required for the phosphorylation and activation of the focal adhesion kinases, p125FAK and PYK2. In addition, our results provide additional new insights into the role of CCK activation of SFK in stimulating the FAKs activation. In the case of p125FAK the Y397 residue (or PYK-2 at Y402), an auto-phosphorylation site, has a strong binding site for SFKs, which in some cases requires SFK binding for its activation, whereas in other cases does not require SFK for the initial activation, but requires it for full activation (Schlaepfer and Hunter, 1996). Our results establish that CCK stimulated phosphorylation of p125FAK at the Y397 and PYK2 at Y402 is SFK-dependent. Our results differ from a number of other studies in various tissues showing that the phosphorylation of FAK at Y397 is a SFK-independent phenomenon, such as seen with the GPCR ligand, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) or bombesin (Salazar and Rozengurt, 2001). Our results with CCK are similar to observations with some other G-protein-coupled-receptors (GPCRs) ligands such as with the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55212-2, whose Y397 FAK phosphorylation action is inhibited by PP2 (Dalton et al, 2013). However, in one study (Hakuno et al, 2005) in embryonic stem cells the degree of p125FAK inhibition induced by SFK inhibitors depended on the nature of the SFK inhibitor used. In that study (Hakuno et al, 2005) the SFK inhibitor SU6656 was not effective in inhibiting p125FAK activation, while PP2 was. Similar varying results with different SFK inhibitors have been reported in a number of studies (Sanchez-Bailon et al, 2012). These results demonstrate the possible difficulties that may occur in relying on a single SFK inhibitor to elucidate the effect of SFK activation in the systems studied (Sanchez-Bailon et al, 2012). Our studies are not limited by this problem, because we provide evidence from three different approaches to support the importance of SFKs in the activation of p125FAK and PYK2.

Our results demonstrate that in pancreatic acini, both CCK and TPA, activate two p125FAK substrates, p130 CAS and paxillin, in a dose-dependent manner as reported previously (Ferris et al, 1999; Sancho et al, 2012), however they extend these results by demonstrating that this activation is Src-dependent for both adapter proteins. Our result in pancreatic acini is similar to that reported in cardiomyocytes where p130CAS is tyrosine phosphorylated by ET1 in a SFK-dependent manner (Kodama et al, 2003). Our results, however, differ from studies in the pancreatic cancer cell line PANC1 where SFK inhibition did not decrease paxillin activation (Nagaraj et al, 2010). These results demonstrate that the role of SFK’s in activating paxillin and p130CAS differs depending on the cell type.

A number of our results establish the novel finding that SFKs are not playing a role either in determining basal activity or in CCK- or TPA- mediated activation of the different mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), p42/44, p38 and JNK. Even though we observed a basal reduction of p42/44 activation after chemical inhibition of SFK, this observation was not corroborated by any of the CSK Ad-virus pre-incubations, demonstrating again the importance of using multiple approaches to altering SFK activity to clearly define its roles. As reported previously, we found that CCK could activate ERK (p42/44) (Dabrowski et al, 1997) and JNK (Dabrowski et al, 1996) and p38 (Schafer et al, 1998) in pancreatic acini. However, there were no studies on the role of SFKs in mediating this effect. We found that SFK’s were not important in CCK or TPA activation of MAPKs in pancreatic acini. These results are in contrast with the effects of substance P in pancreatic acinar cells (Ramnath et al, 2009), bradykinin in trabecular meshwork cells (Webb et al, 2011), urocortin in mouse myocytes (Yuan et al, 2010) or angiotensin II in vascular smooth cells (Yogi et al, 2007), which all stimulate Src-dependent p42/44 activation. However, they are similar to results in vascular smooth cells stimulated by ET-1, which activated ERKs in a Src-independent way (Yogi et al, 2007). Our findings also establish that CCK/TPA induced activation of p38 is not depend on Src activation. These results differ from that seen with sphingosine-1-phosphate stimulation in smooth muscle cells (Duru et al, 2012) or angiotensin II stimulation of p38 in vascular smooth cells (Duru et al, 2012), which caused Src-dependent activation of p38. However, they are similar to the lack of effect of SFK activity on ET-1 stimulation in vascular smooth muscle cells (Yogi et al, 2007). Lastly, we also found that alteration of SFK activity did not affect CCK or TPA activation of JNK, which differs from JNK activation induced by sphingosine-1-phosphate in smooth muscle cells or by ET-1 stimulation in vascular smooth, which is dependent on Src (Yogi et al, 2007; Duru et al, 2012). However, our result in pancreatic acinar cells is similar to the lack of effect of Src inhibition on angiotensin II stimulation of JNK in vascular smooth muscle cells (Duru et al, 2012). These results demonstrate that the lack of importance of SFK in mediating activation of different MAPKs in pancreatic acinar cells generally differs from its importance in this cascade with various stimuli in other cell types.

In previous studies in pancreatic acini, CCK is reported to stimulate Shc (Piiper et al, 2003), alter the activation of Akt (Berna et al, 2009) and also stimulate phosphorylation of GSK-3β (Sans et al, 2002), resulting in alterations in their activity. Our results reveal that, in pancreatic acinar cells, Shc activation induced by CCK or TPA and also Shc’s basal activity were SFK-dependent. These results are consistent with observations from previous studies in pancreatic acinar cells, in which CCK stimulated the association of Shc with the SFK members, Yes and Lyn (Sancho et al, 2012; Pace et al, 2006), however in these studies no evidence was provided that this interaction resulted in activation of Shc. These results are similar to activation of growth factor receptors on NIH-3T3 and in human epidermoid carcinoma cells, which results in both an interaction of Shc with activated SFKs and an activation of Shc (Sato et al, 2005; Sato et al, 2002). In a previous study (Daulhac et al, 1999) in CHO cells incubated with the CCKB receptor agonist, gastrin, p42/44 activation occurred via Shc activation mediated by SFK. This result differs from our study in pancreatic acini because, while Shc activation mediated by CCK is Src-dependent, p42/44 activation is not, demonstrating a Shc-independent p42/44 activation induced by CCK in pancreatic acini. In our study, stimulation by CCK and TPA altered Akt activation and with changes in SFK activation, the effect of CCK or TPA on Akt activation was not altered, which is consistent with findings in a previous study, using only a SFK inhibitor (Berna et al, 2009). However, in our study alteration of SFK activity resulted in a decrease in basal Akt activity. Our results of Src inhibition on basal Akt activation are consistent with previous results in pancreatic cancer and CHO cells (Nagaraj et al, 2010; Olianas et al, 2011). In our study we did not observe an effect of CCK or TPA upon GSK-3-β activity or an effect of altering SFK activity on CCK or TPA lack of effect on GSK-3-β activity. We did, however, observe a slight reduction of GSK-3-β basal levels with SFK chemical inhibition, although this observation was not confirmed by any of the CSK-Ad virus preincubations. This result raises the question, if the previous reports on the inhibition of basal GSK-3-β activity by PP2 in other cell systems (Takadera et al, 2012; Olianas et al, 2011) were due to a direct SFK inhibition or to PP2 interacting with other signaling pathways. Our results are similar to studies in HEK-293, SH-SY5Y and CHO cells, where Src-inhibition did not reduced the basal phosphorylation of GSK-3β (Cole et al, 2004).

CCK has been reported to activate a number of PKCs in pancreatic acini (Sancho et al, 2012; Pace et al, 2006), primarily by a PKD-dependent mechanism, and this activation is important in mediating a number of cellular responses including differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, cell death, secretion, adhesion and cell migration (Gorelick et al, 2008). In general there are few studies on the role of SFKs in CCK/TPA mediated PKC activation in pancreatic acinar cells and moreover, in the studies available, conflicting results are reported. Our results help resolve these conflicting conclusions, by showing that CCK-stimulation of PKCs in pancreatic acinar cells is not dependent on alterations in SFK activation by any of the three methods used. This conclusion is supported by the fact that activation of PKD or MARCKS, which is a PKC substrate, by CCK or TPA, was not altered by any of the means used to modulate SFK activity. Our results are consistent with studies in endothelial and epithelial cells where PKC activation by TNF is not Src-dependent (Tatin et al, 2006; Huang et al, 2003), however, they differ from stimulation of PKC in keratinocytes, which is dependent on Src (Joseloff et al, 2002). The results also differ from those in study (Sancho et al, 2012) in pancreatic acinar cells which reported CCK stimulated the association of the SFK, Yes, with PKD or Lyn with PKC (Sancho et al, 2012), compatible with their activation, or with the observation that SFK mediates PKD activation in response to stress in 3T3 fibroblasts (Waldron and Rozengurt, 2000). However, our results are consistent with another study in pancreatic acinar cells (Berna et al, 2007) in which SFK inhibition by a single SFK inhibitor did not inhibit the CCK activation of PKD. An alternative explanation that is compatible with our results and these seemly divergent effects in pancreatic acini is that the association of SFK with PKD or Lyn with PKC, previously reported (Sancho et al, 2012), results not in PKD/PKC activation, but instead in SFK activation. This proposal is consistent with the finding that in pancreatic acini the activation of the SFK, Yes(Sancho et al, 2012) and well as Lyn (Sancho et al, 2012), is PKC dependent. These results demonstrate that the role of SFK in activating PKCs can vary markedly in different cells.

In conclusion in this study by using three different approaches to altering Src activity, it allowed us to amplify the knowledge about the roles of SFKs in acinar cell signaling. These approaches included, inhibition by adenovirus inactivation of SFK activity or by over-activating SFK using a dominant-negative adenovirus construct and pharmacological inhibition accompanied by an inactive control. This has allowed us to investigate the role of SFK in modulating cellular cascades that are reported to be important in mediating numerous CCK-mediated physiological and pathophysiological effects involved in tumor growth, proliferation, angiogenesis, survival, motility, migration and secretion.

Our results demonstrate CCK activation of SFK under physiological conditions plays an important role in the activation of the focal adhesion kinases (p125FAK, PYK2) and paxillin, but not in the activation of Shc, MAPKs (p38, JNK, p42/44), GSK-3β or protein-kinases C or D. However, under pathophysiological conditions induced by supramaximal CCK concentrations, used to induce acute pancreatitis in vitro (Yuan et al, 2012), SFKs is also important for the activation of p130CAS and Shc.

These results show that in pancreatic acinar cells, SFKs play a much wide role than previously reported in activating a number of important cellular signaling cascades shown to be important in mediating both acinar cell physiological and pathophysiological responses.

5. Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by intramural funds of NIDDK, NIH.

Abbreviations

- CCK

COOH-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin

- TPA

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate

- SFK

Src family of kinases

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PYK2

proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2

- FAK

p125 focal adhesion kinase

- Shc

Src homology 1 domain containing transforming protein

- PKD

protein kinase D

- CAS

Crk-associated substrate

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- AKT

protein kinase B

- MAPK/ERK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- JNK

c-Jun-N-terminal kinase

- GSK3-β

glycogen synthase kinase 3

- MARCKS

myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate

- PP2

4-Amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine

- PP3

4-Amino-7-phenylpyrazol[3,4-d]pyrimidine

- CSK

c-Src kinase

- DN

Dominant negative

- WT

Wild type

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

6. References

- Adam AP, Sharenko AL, Pumiglia K, Vincent PA. Src-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin is not sufficient to decrease barrier function of endothelial monolayers. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7045–7055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleshin A, Finn RS. SRC: a century of science brought to the clinic. Neoplasia. 2010;12:599–607. doi: 10.1593/neo.10328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonieta Cote-Velez MJ, Ortega E, Ortega A. Involvement of pp125FAK and p60SRC in the signaling through Fc gamma RII-Fc gamma RIII in murine macrophages. Immunol Lett. 2001;78:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(01)00251-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain J, Plater L, Elliott M, Shpiro N, Hastie CJ, McLauchlan H, Klevernic I, Arthur JS, Alessi DR, Cohen P. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berna MJ, Hoffmann KM, Tapia JA, Thill M, Pace A, Mantey SA, Jensen RT. CCK causes PKD1 activation in pancreatic acini by signaling through PKC-delta and PKC-independent pathways. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:483–501. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berna MJ, Tapia JA, Sancho V, Thill M, Pace A, Hoffmann KM, Gonzalez-Fernandez L, Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal growth factors and hormones have divergent effects on Akt activation. Cell Signal. 2009;21:622–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia M. Apoptosis of pancreatic acinar cells in acute pancreatitis: is it good or bad? J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:402–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake RA, Broome MA, Liu X, Wu J, Gishizky M, Sun L, Courtneidge SA. SU6656, a selective Src family kinase inhibitor, used to probe growth factor signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:9018–9027. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.23.9018-9027.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole A, Frame S, Cohen P. Further evidence that the tyrosine phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) in mammalian cells is an autophosphorylation event. Biochem J. 2004;377:249–255. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski A, Grady T, Logsdon CD, Williams JA. Jun kinases are rapidly activated by cholecystokinin in rat pancreas both in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5686–5690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowski A, Groblewski GE, Schafer C, Guan KL, Williams JA. Cholecystokinin and EGF activate a MAPK cascade by different mechanisms in rat pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1472–C1479. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton GD, Peterson LJ, Howlett AC. CB1 cannabinoid receptors promote maximal FAK catalytic activity by stimulating cooperative signaling between receptor tyrosine kinases and integrins in neuronal cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1665–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daulhac L, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Pradayrol L, Vaysse N, Seva C. Src-family tyrosine kinases in activation of ERK-1 and p85/p110-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by G/CCKB receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20657–20663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duru EA, Fu Y, Davies MG. SRC regulates sphingosine-1-phosphate mediated smooth muscle cell migration. J Surg Res. 2012;175:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris HA, Tapia JA, Garcia LJ, Jensen RT. CCKA receptor activation stimulates p130cas tyrosine phosphorylation, translocation, and association with Crk in rat pancreatic acinar cells. Biochemistry (Mosc) 1999;38:1497–1508. doi: 10.1021/bi981903w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia LJ, Rosado JA, Gonzalez A, Jensen RT. Cholecystokinin-stimulated tyrosine phosphorylation of p125FAK and paxillin is mediated by phospholipase C-dependent and -independent mechanisms and requires the integrity of the actin cytoskeleton and participation of p21rho. Biochem J. 1997;327:461–472. doi: 10.1042/bj3270461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George TJ, Jr, Trevino JG, Liu C. Src inhibition is still a relevant target in pancreatic cancer. Oncologist. 2014;19:211. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick F, Pandol S, Thrower E. Protein kinase C in the pancreatic acinar cell. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23 Suppl. 2008;1:S37–S41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakuno D, Takahashi T, Lammerding J, Lee RT. Focal adhesion kinase signaling regulates cardiogenesis of embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39534–39544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505575200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Chen JJ, Inoue H, Chen CC. Tyrosine phosphorylation of I-kappa B kinase alpha/beta by protein kinase C-dependent c-Src activation is involved in TNF-alpha-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression. J Immunol. 2003;170:4767–4775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseloff E, Cataisson C, Aamodt H, Ocheni H, Blumberg P, Kraker AJ, Yuspa SH. Src family kinases phosphorylate protein kinase C δ on tyrosine residues and modify the neoplastic phenotype of skin keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12318–12323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama H, Fukuda K, Takahashi E, Tahara S, Tomita Y, Ieda M, Kimura K, Owada KM, Vuori K, Ogawa S. Selective involvement of p130Cas/Crk/Pyk2/c-Src in endothelin-1-induced JNK activation. Hypertension. 2003;41:1372–1379. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000069698.11814.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle RA. Cholecystokinin. In: Walsh JH, Dockray GJ, editors. Gut Peptides. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 175–216. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra V, Cline R, Noel P, Karlsson J, Baty CJ, Orlichenko L, Patel K, Trivedi RN, Husain SZ, Acharya C, Durgampudi C, Stolz DB, Navina S, Singh VP. Src Dependent Pancreatic Acinar Injury Can Be Initiated Independent of an Increase in Cytosolic Calcium. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y, Fukazawa H, Mizuno S, Uehara Y. Effect of herbimycin A on tyrosine kinase receptors and platelet derived growth factor (PDGF)-induced signal transduction. Biol Pharm Bull. 1998;21:1030–1035. doi: 10.1248/bpb.21.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj NS, Smith JJ, Revetta F, Washington MK, Merchant NB. Targeted inhibition of SRC kinase signaling attenuates pancreatic tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:2322–2332. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M. Regulation of the SRC family kinases by Csk. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8:1385–1397. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olianas MC, Dedoni S, Onali P. Regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling by N-desmethylclozapine through activation of delta-opioid receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;660:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace A, Garcia-Marin LJ, Tapia JA, Bragado MJ, Jensen RT. Phosphospecific site tyrosine phosphorylation of p125FAK and proline-rich kinase 2 is differentially regulated by cholecystokinin receptor A activation in pancreatic acini. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19008–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace A, Tapia JA, Garcia-Marin LJ, Jensen RT. The Src family kinase, Lyn, is activated in pancreatic acinar cells by gastrointestinal hormones/neurotransmitters and growth factors which stimulate its association with numerous other signaling molecules. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piiper A, Elez R, You SJ, Kronenberger B, Loitsch S, Roche S, Zeuzem S. Cholecystokinin stimulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase through activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor, Yes, and protein kinase C. Signal amplification at the level of Raf by activation of protein kinase Cepsilon. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7065–7072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramnath RD, Sun J, Bhatia M. Involvement of SRC family kinases in substance P-induced chemokine production in mouse pancreatic acinar cells and its significance in acute pancreatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:418–428. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.148684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar EP, Rozengurt E. Src family kinases are required for integrin-mediated but not for G protein-coupled receptor stimulation of focal adhesion kinase autophosphorylation at Tyr-397. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17788–17795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Bailon MP, Calcabrini A, Gomez-Dominguez D, Morte B, Martin-Forero E, Gomez-Lopez G, Molinari A, Wagner KU, Martin-Perez J. Src kinases catalytic activity regulates proliferation, migration and invasiveness of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1276–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancho V, Nuche-Berenguer B, Jensen RT. The Src kinase Yes is activated in pancreatic acinar cells by gastrointestinal hormones/neurotransmitters, but not pancreatic growth factors, which stimulate its association with numerous other signaling molecules. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans MD, Kimball SR, Williams JA. Effect of CCK and intracellular calcium to regulate eIF2B and protein synthesis in rat pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G267–G276. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00274.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Iwasaki T, Fukami Y. Association of c-Src with p52Shc in mitotic NIH3T3 cells as revealed by Src-Shc binding site-specific antibodies. J Biochem. 2005;137:61–67. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Nagao T, Kakumoto M, Kimoto M, Otsuki T, Iwasaki T, Tokmakov AA, Owada K, Fukami Y. Adaptor protein Shc is an isoform-specific direct activator of the tyrosine kinase c-Src. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29568–29576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer C, Ross SE, Bragado MJ, Groblewski GE, Ernst SA, Williams JA. A role for the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/Hsp 27 pathway in cholecystokinin-induced changes in the actin cytoskeleton in rat pancreatic acini. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24173–24180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.24173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaepfer DD, Hunter T. Evidence for in vivo phosphorylation of the Grb2 SH2-domain binding site on focal adhesion kinase by Src-family protein-tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5623–5633. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takadera T, Fujibayashi M, Koriyama Y, Kato S. Apoptosis induced by SRC-family tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cultured rat cortical cells. Neurotox Res. 2012;21:309–316. doi: 10.1007/s12640-011-9284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia JA, Ferris HA, Jensen RT, Marin LJ. Cholecystokinin activates PYK2/CAKβ, by a phospholipase C-dependent mechanism, and its association with the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31261–31271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.44.31261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapia JA, Garcia-Marin LJ, Jensen RT. Cholecystokinin-stimulated protein kinase C-delta activation, tyrosine phosphorylation and translocation is mediated by Src tyrosine kinases in pancreatic acinar cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;12:35220–35230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatin F, Varon C, Genot E, Moreau V. A signalling cascade involving PKC, Src and Cdc42 regulates podosome assembly in cultured endothelial cells in response to phorbol ester. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:769–781. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda Y, Yoshida H, Africa L, Steil GJ, Owyang C. Src kinase pathways in extracellular Ca2+-dependent pancreatic enzyme secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:876–884. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron RT, Rozengurt E. Oxidative stress induces protein kinase D activation in intact cells. Involvement of Src and dependence on protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17114–17121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908959199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JG, Yang X, Crosson CE. Bradykinin activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases in human trabecular meshwork cells. Exp Eye Res. 2011;92:495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yogi A, Callera GE, Montezano AC, Aranha AB, Tostes RC, Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. Endothelin-1, but not Ang II, Activates MAP Kinases Through c-Src-Independent Ras-Raf-Dependent Pathways in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1960–1967. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.146746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Liu Y, Tan T, Guha S, Gukovsky I, Gukovskaya A, Pandol SJ. Protein kinase d regulates cell death pathways in experimental pancreatitis. Front Physiol. 2012;3:60. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z, McCauley R, Chen-Scarabelli C, Abounit K, Stephanou A, Barry SP, Knight R, Saravolatz SF, Saravolatz LD, Ulgen BO, Scarabelli GM, Faggian G, Mazzucco A, Saravolatz L, Scarabelli TM. Activation of Src protein tyrosine kinase plays an essential role in urocortin-mediated cardioprotection. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;325:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]