Abstract

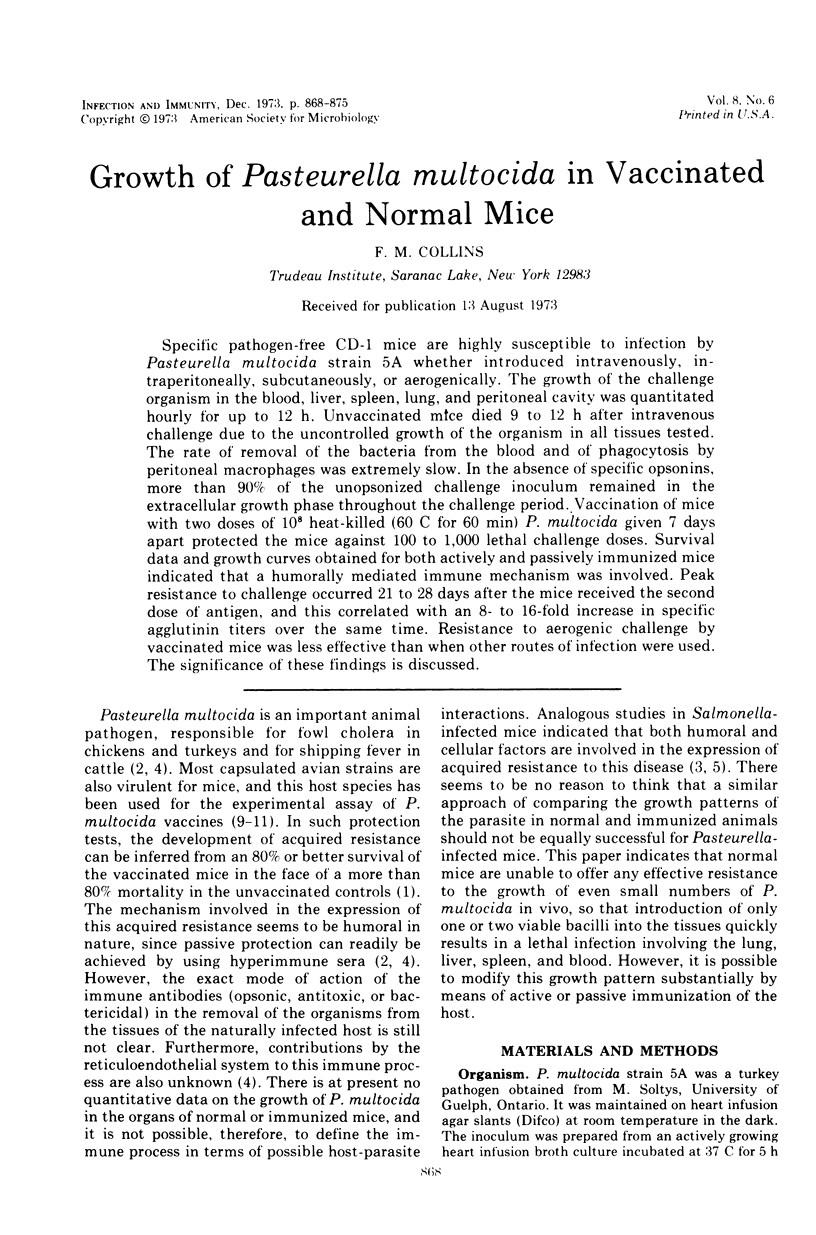

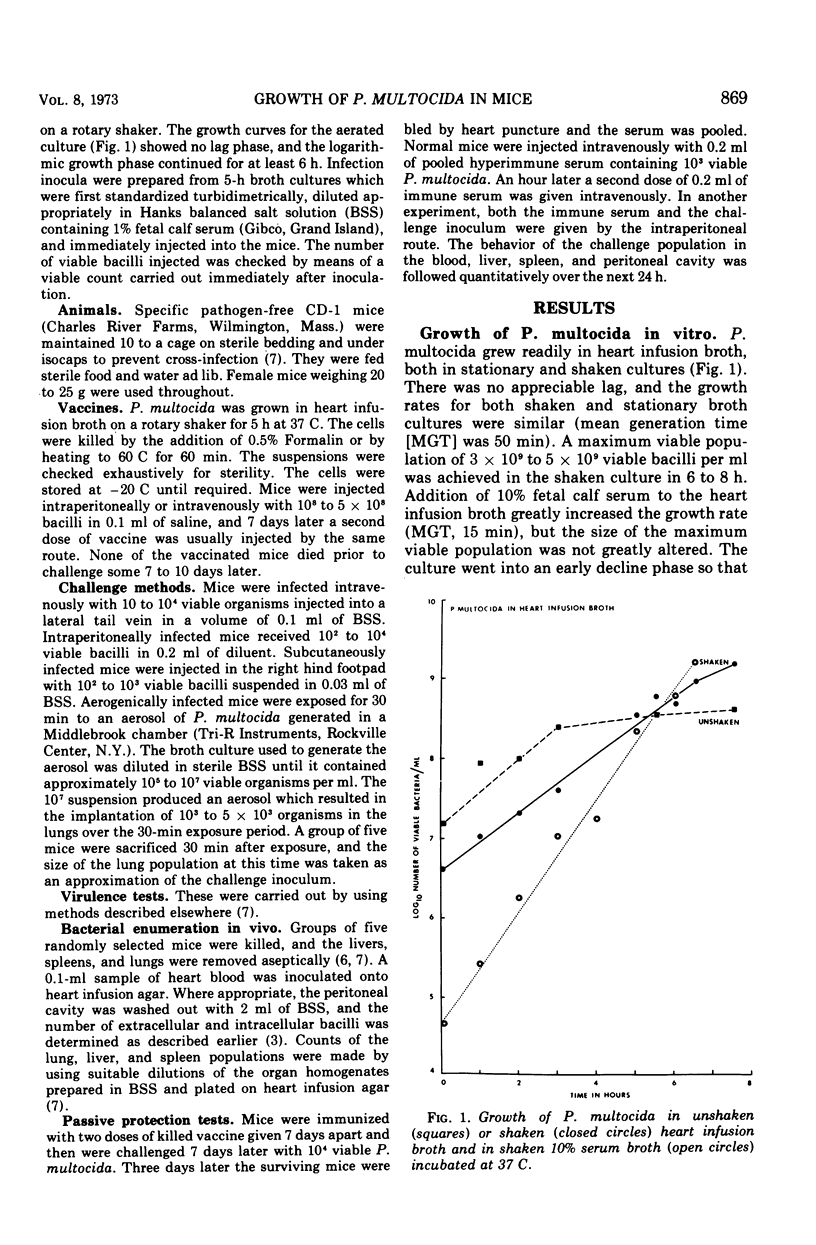

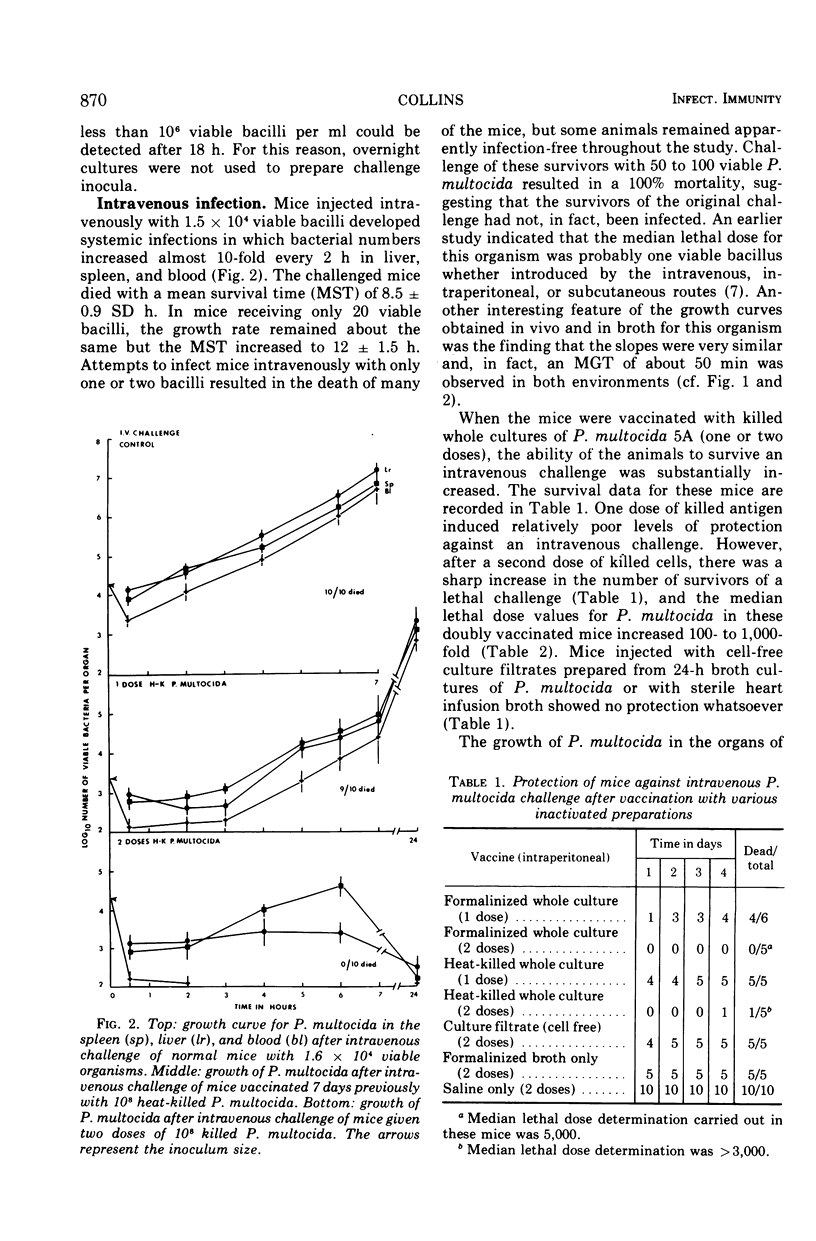

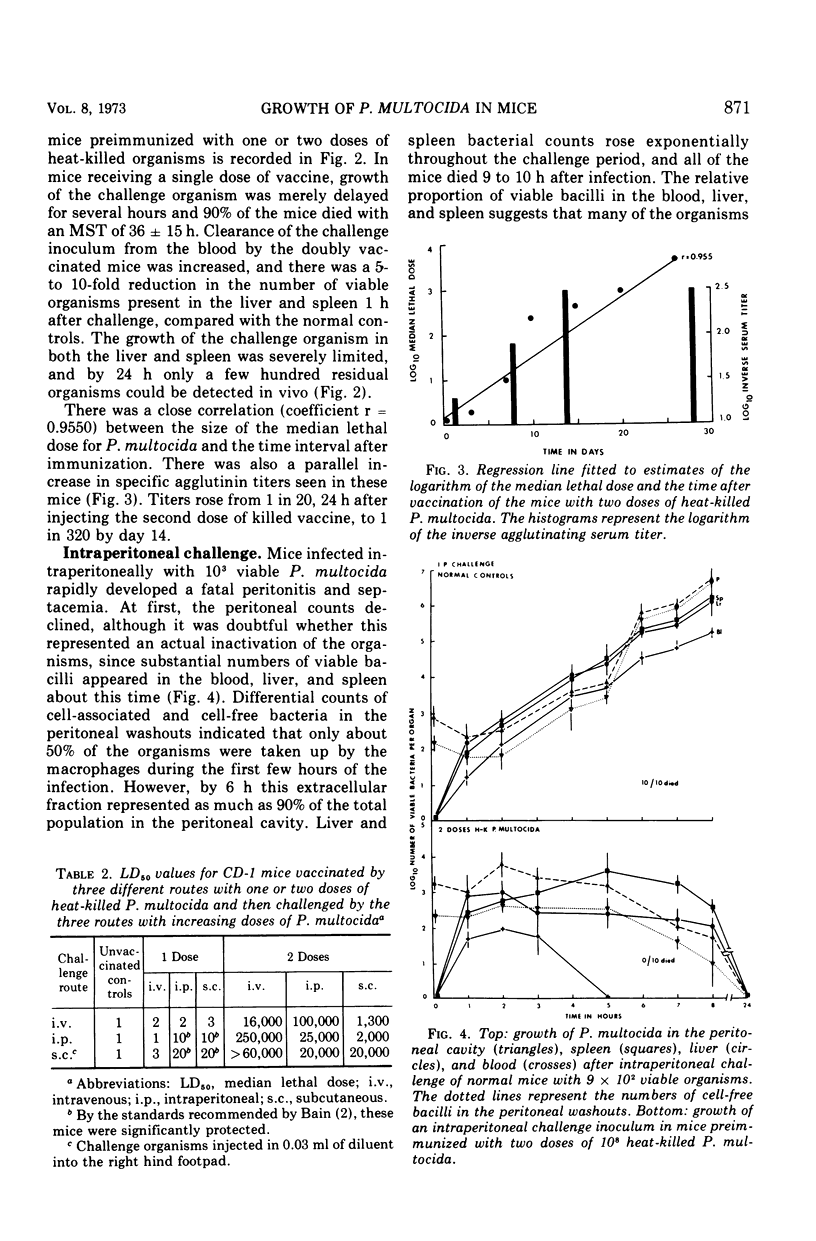

Specific pathogen-free CD-1 mice are highly susceptible to infection by Pasteurella multocida strain 5A whether introduced intravenously, intraperitoneally, subcutaneously, or aerogenically. The growth of the challenge organism in the blood, liver, spleen, lung, and peritoneal cavity was quantitated hourly for up to 12 h. Unvaccinated mice died 9 to 12 h after intravenous challenge due to the uncontrolled growth of the organism in all tissues tested. The rate of removal of the bacteria from the blood and of phagocytosis by peritoneal macrophages was extremely slow. In the absence of specific opsonins, more than 90% of the unopsonized challenge inoculum remained in the extracellular growth phase throughout the challenge period. Vaccination of mice with two doses of 108 heat-killed (60 C for 60 min) P. multocida given 7 days apart protected the mice against 100 to 1,000 lethal challenge doses. Survival data and growth curves obtained for both actively and passively immunized mice indicated that a humorally mediated immune mechanism was involved. Peak resistance to challenge occurred 21 to 28 days after the mice received the second dose of antigen, and this correlated with an 8- to 16-fold increase in specific agglutinin titers over the same time. Resistance to aerogenic challenge by vaccinated mice was less effective than when other routes of infection were used. The significance of these findings is discussed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alls A. A., Appleton G. S., Ipson J. R. A bird-contact method of challenging turkeys with Pasteurella multocida. Avian Dis. 1970 Feb;14(1):172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanden R. V., Mackaness G. B., Collins F. M. Mechanisms of acquired resistance in mouse typhoid. J Exp Med. 1966 Oct 1;124(4):585–600. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.4.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter G. R. Pasteurellosis: Pasteurella multocida and Pasteurella hemolytica. Adv Vet Sci. 1967;11:321–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Carter P. B. Comparative immunogenicity of heat-killed and living oral Salmonella vaccines. Infect Immun. 1972 Oct;6(4):451–458. doi: 10.1128/iai.6.4.451-458.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M. Immunogenicity of living and heat-killed Salmonella pullorum vaccines. Infect Immun. 1973 May;7(5):735–742. doi: 10.1128/iai.7.5.735-742.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M. Mechanisms in antimicrobial immunity. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1971 Jul;10(1):58–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heddleston K. L., Rebers P. A. Pasteurella multocida: immune response in chicks and mice. Proc Annu Meet U S Anim Health Assoc. 1969;73:280–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURATA M., HORIUCHI T., NAMIOKA S. STUDIES ON THE PATHOGENICITY OF PASTEURELLA MULTOCIDA FOR MICE AND CHICKENS ON THE BASIS OF O-GROUPS. Cornell Vet. 1964 Apr;54:293–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]