Abstract

Thermal expansion, defined as the temperature dependence of volume under constant pressure, is a common phenomenon in nature and originates from anharmonic lattice dynamics. However, it has been poorly understood how thermal expansion can show anomalies such as colossal positive, zero, or negative thermal expansion (CPTE, ZTE, or NTE), especially in quantitative terms. Here we show that changes in configurational entropy due to metastable micro(scopic)states can lead to quantitative prediction of these anomalies. We integrate the Maxwell relation, statistic mechanics, and first-principles calculations to demonstrate that when the entropy is increased by pressure, NTE occurs such as in Invar alloy (Fe3Pt, for example), silicon, ice, and water, and when the entropy is decreased dramatically by pressure, CPTE is expected such as in anti-Invar cerium, ice and water. Our findings provide a theoretic framework to understand and predict a broad range of anomalies in nature in addition to thermal expansion, which may include gigantic electrocaloric and electromechanical responses, anomalously reduced thermal conductivity, and spin distributions.

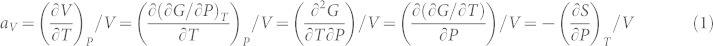

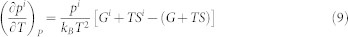

Thermal expansion of materials, defined as the change of volume with respect to temperature under constant pressure, is one of the most common phenomena in nature. It has been studied through the asymmetric feature of interatomic force as a function of atomic distance, i.e., the anharmonic lattice dynamics. Even though ZTE and NTE have been observed for over a century1,2, current understanding is still largely qualitative and phenomenological3,4,5, or based on phonon measurements and/or calculations for a single phase6 (similar to the cases of Si and ice shown in this Report). This is probably because one has been focusing on the effects of temperature and searching for answers inside an individual stable microstate without considering the outside influences from metastable microstates. Here, we point out that the temperature dependence of volume under constant pressure can be transformed to the pressure dependence of entropy under constant temperature through the Maxwell relation, resulting in the volume thermal expansion coefficient, αV, expressed as follows7

|

where V is the volume, T the temperature, P the pressure, G the Gibbs free energy, and S the entropy. The outcome of equation (1) circumvents the complexity of lattice dynamics as a function of temperature and introduces quantitative understanding of thermal expansion in terms of entropy. In materials with positive thermal expansion, i.e. αV > 0, equation (1) shows that the entropy decreases with increasing pressure, while for those with negative thermal expansion, i.e. αV < 0, the entropy must increase with pressure. Therefore, the entropy of materials can either decrease or increase with pressure even though it always increases with temperature in a stable system due to the stability requirements7.

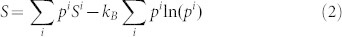

In statistical thermodynamics, entropy is related to the number of microstates (i) and their probabilities being occupied (pi). Let us consider a homogeneous single phase at equilibrium with a statistical ensemble over a number of unique microstates with each microstate representing a given atomic, magnetic, or polar configuration. Based on classic thermodynamics, one microstate is stable with the lowest free energy, conventionally called ground state, while all other microstates with higher free energies are metastable with their probabilities of existence determined by statistic mechanics. However, in statistic thermodynamics, the metastable microstates may be incorporated into the global thermodynamic equilibrium as discussed in the present work, potentially introducing anomalous behaviors into the system.

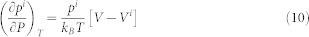

As shown in the Method section, the entropy of such a system can be expressed as follows

|

with Si being the entropy of the microstate i, and kB the Boltzmann constant. The typical contributions to entropy of an individual microstate include thermal electrons and lattice dynamics and can be computed from first-principles calculations based on the density functional theory8. Equation (2) shows that in addition to the weighted average of entropies of all microstates, there is an additional contribution to the total entropy due to the mixture between the stable microstate and other metastable microstates, denoted by the microstate configurational entropy (MCE),  .

.

Results and Discussion

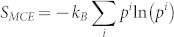

Let us analyze a system starting with one microstate only, α. When a metastable microstate, β, is introduced by decreasing or increasing pressure under constant temperature, the entropy change of the system can be written as

|

Since the present interest is on volume change with respect to the increase of temperature, we are thus concerned with the situations when the stability of metastable β microstate relative to the α microstate increases with temperature, i.e. Sβ > Sα, resulting in a positive entropy change of equation (3), i.e. ΔS > 0, knowing the fact that SMCE cannot be negative. It should be noted that the assumption of Sβ > Sα is only for the convenience of the discussion and does not affect the conclusions. If this entropy increase is due to the decrease of pressure, i.e. Vβ > Vα, the volume thermal expansion of the system is positive, while if this entropy increase is realized by increasing pressure, i.e. Vβ < Vα, the volume thermal expansion of the system is negative, as shown by equation (1). If the entropy change due to pressure is large, colossal positive or negative thermal expansion occurs.

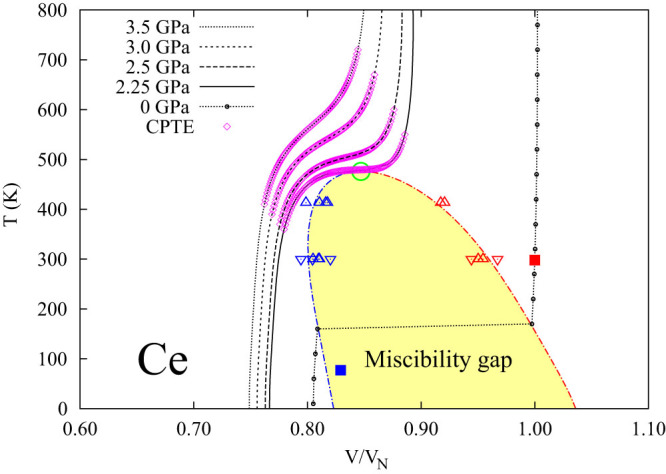

For the CPTE case, the anti-Invar cerium is investigated as a proof of concept with two microstates of the same fcc lattice, but one being the nonmagnetic ground state and the other being the metastable ferromagnetic state under ambient pressure9. At 0 K, the volume of the nonmagnetic ground state is only 81% of that of the metastable magnetic microstate. The isobaric volumes at five pressures are plotted in Fig. 1 as a function of temperature obtained by means of statistic mechanics and free energy minimization with details in the Method section and ref. 9. The miscibility gap and available experimental data10,11,12 are also included in Fig. 1. In the pressure range of 2.25–3.5 GPa, the system is within the single-phase region at all temperatures considered. In this pressure range, normal thermal expansion is observed at both low and high temperatures on each isobaric curve where the probability of each microstate does not change significantly with temperature9. While in the middle temperature range on each isobaric curve, CPTE, highlighted by the pink open diamond symbols, exists due to the fast increase of probability of the metastable microstate with respect to temperature. This CPTE is much higher than the individual positive thermal expansions of the stable and metastable microstates, respectively.

Figure 1. Isobaric volumes of Ce at five pressures.

The volume (V) is normalized to its equilibrium volume (VN) at atmospheric pressure and room temperature. The predicted CPTE regions are illustrated by the pink open diamonds. Below the critical point marked by the green open circle, the single phase is no longer stable and decomposes into a two-phase mixture in the area of miscibility gap. Measured volumes at zero pressure by Koskimaki et al.10 are shown by solid squares, and experimental data of miscibility gap phase boundaries are measured by Schiwek et al. (the open up-triangles)11, and Zachariasen and Ellinger (the open down-triangles)12.

With decreasing pressure, the system reaches a critical point (green circle) where the single phase becomes unstable, represented by  and

and  , and both entropy and volume change colossally7. At even lower pressure, a miscibility gap forms, and the single phase separates into two phases with the same fcc crystal structures, but different magnetic spin structures. Inside the miscibility gap, the volume changes discontinuously with respect to temperature by the so-called first-order transition as shown by the isobaric curve at zero pressure7, compared well with experimental volume data (solid squares) under ambient pressure10.

, and both entropy and volume change colossally7. At even lower pressure, a miscibility gap forms, and the single phase separates into two phases with the same fcc crystal structures, but different magnetic spin structures. Inside the miscibility gap, the volume changes discontinuously with respect to temperature by the so-called first-order transition as shown by the isobaric curve at zero pressure7, compared well with experimental volume data (solid squares) under ambient pressure10.

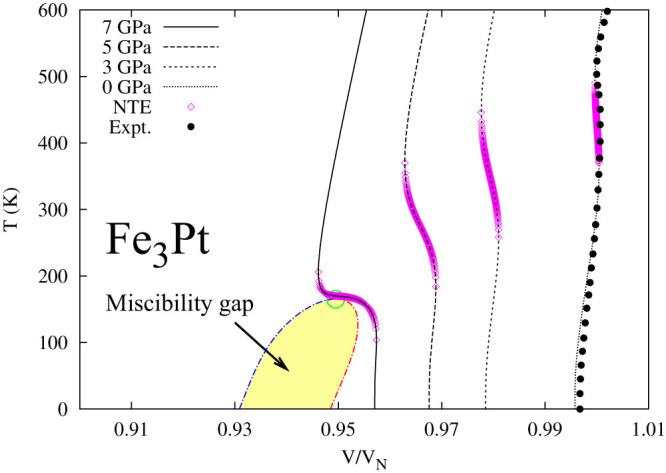

For the NTE case, we study an Invar alloy Fe3Pt with 29 = 512 microstates of different magnetic spin configurations, showing negative thermal expansion in the range of 289-449 K under atmospheric pressure13,14. First-principles calculations predict that the ferromagnetic microstate has the largest volume and is the stable state up to 900 K under atmospheric pressure. Figure 2 shows the temperature dependence of isobaric volume of Fe3Pt at ambient pressure in excellent agreement with experimental data14. It also depicts the gigantic NTE around the critical point on the isobaric curve at 7 GPa and a temperature range of NTE on each isobaric curve due to the SMCE. It can thus be seen that the origin of NTE in a single phase is the statistic existence of metastable microstates with lower volumes and higher entropies than the stable state in a temperature range where their probabilities change dramatically. This conclusion was validated by examining the temperature-pressure phase diagrams of materials with the negative thermal expansion observed experimentally15, including zirconium tungstate16,17,18 for which the amorphous phase is indicated to be the high-entropy and low-volume microstate.

Figure 2. Isobaric volumes of Fe3Pt at four pressures.

The volume (V) is normalized to its equilibrium volume (VN) at atmospheric pressure and room temperature. The predicted NTE regions are illustrated by the pink open diamonds13. Measured variation of volume at ambient pressure by Sumiyama et al.14 is also shown for comparison. The shaded area represents the miscibility gap similar to that in Fig. 1 with the critical point marked by the green open circle.

Another important case of thermal expansion anomaly is H2O. Experimental observations under atmospheric pressure show that ice exhibits NTE from zero to 70 K and positive thermal expansion from 70 K until melting19,20, while the water has NTE at temperatures below 277.134 K (3.984°C)21,22.

A convincing explanation of NTE of ice from zero K to 70 K was given by Tanaka23. He constructed 100 ice configurations of proton-disordered form with zero net dipole moment and obtained the density of state for intermolecular vibration by simple average of those configurations with the harmonic assumption. This is in principle similar to our approach presented above for cerium and Fe3Pt though in our approach free energies of individual microstates are predicted by first-principles calculations, and their weighted average is obtained through statistical mechanics9,13. Based on our theory, the metastable configurations that Tanaka constructed should have their free energies close to that of the ground state, but have smaller volume and higher entropy such as various amorphous ices, i.e. supercooled liquid (see further discussion later), though it was not explicitly stated by Tanaka. This may also explain the anomalous reduction in thermal conductivity, shear modulus, and transverse sound velocity in hexagonal and cubic ices with increasing pressure because the probability of amorphous ices increases and their random fluctuation enhances the scattering effect, which will be discussed in separate publications.

The interpretation of thermal expansion anomaly of water in the literature is far less satisfactory due to the complex structures of liquid in general24,25,26,27,28. However, the recent breakthrough in experiments demonstrated the inhomogeneous structure of water at ambient conditions, showing the presence of nanometer-scale density fluctuations in ambient water with their spectral features similar to those of vapor and ice29. At temperatures close to or below the freezing temperature, the probability of metastable (above 0°C) or stable (below 0°C) ice microstates in stable or metastable water becomes significant. With the entropies and volumes of ice and water in the order of Swater > Sice and Vwater < Vice, our theory indicates that the entropy of water increases with pressure at constant temperature due to the reduced probability of metastable ice microstate (lower entropy and larger volume), resulting in ZTE at 277.134 K and NTE below 277.134 K in water. At higher temperatures, the probability of metastable ice microstate in water becomes negligibly small, resulting in normal positive thermal expansion in water. At even higher temperatures, the probability of metastable vapor microstate in water increases significantly due to the reduced free energy difference between the two microstates, resulting in a volume CPTE of 6.87 × 10−4/K at 368 K (95°C)30. Our theory is in accordance with the two-state thermodynamics for supercooled water27,28, the distributed charge states31, and the multiple metastable phase models32,33.

Our theory provides further insights into the origin of NTE of ice from zero K to 70 K and the CPTE of ice near melting. There is a triple point between two ice structures and vapor at zero pressure and 72.15 K34, indicating that the vapor is unstable below this temperature under ambient pressure. The metastable amorphous ice, i.e. supercooled water, thus induces NTE in ice because the entropy of ice is increased by pressure due to the higher entropy and smaller volume of various metastable amorphous microstates. At 72.15 K, i.e. the temperature of the triple point, the vapor microstate becomes metastable under ambient pressure. With Vice ≪ Vvapor and Sice ≪ Svapor, the entropy of ice increases with decreasing pressure, resulting in positive thermal expansion above the temperature of the triple point and a volume CPTE of 1.59 × 10−4/K before melting19,20 due to the metastable vapor microstate. The liquid/amorphous microstates play less important role due to their much smaller entropy and volume in comparison with those of the vapor microstate. This also explains why the approach by Tanaka23 works because the energies of the ground state and the metastable microstates are close to each other at zero K, and those metastable microstates contribute to phonon properties calculated at zero K in the form of phonon anomaly. This is demonstrated by the prediction of NTE in ice and silicon by means of first-principles phonon calculations as shown below with the calculation details presented in the Method section.

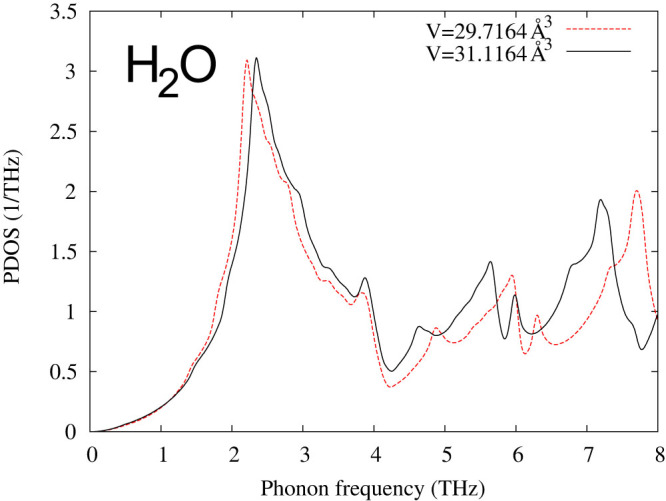

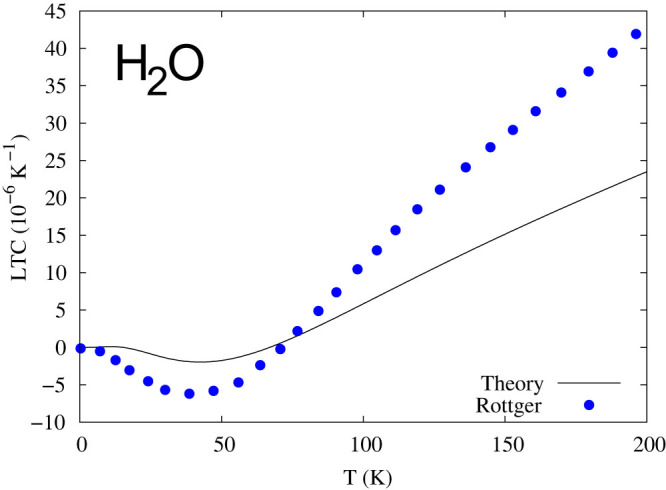

When the energies of the stable and metastable microstates are close to each other at zero K, their phonon-phonon interactions may take place in the form of phonon anomaly. One such example is given for ice in Fig. 3, showing the abnormal volume dependence of the phonon density of states with significant increase at frequencies lower than 2.3 THz in the smaller volume. The resulted negative thermal expansion is shown in Fig. 4 up to 70 K compared with experimental data by Rottger et al.20. It is noted that the thermal expansion predicted from first-principles phonon calculations is not as negative as experiments at low temperatures, but much lower than experiments at high temperatures in Fig. 4. This is probably because the energy differences between the stable and some metastable high-pressure microstates are beyond the phonon energy of the stable microstate at zero K as recently noted by Hermann et al. who reported a sequence of new stable and meta-stable structures for the ground state of ice with increasing pressure35. Similarly, the contribution from the metastable vapor microstate at high temperatures cannot be reflected in the phonon spectrum of the stable microstate at zero K either. However, the excitation of phonons at higher temperatures can reach the energy levels of those metastable microstates in experiments, resulting in the larger anharmonic behaviors in the system at finite temperatures as shown in cerium and Fe3Pt9,13. The phonon anomalies in several materials at finite temperatures have been reported experimentally by Manley and co-workers using inelastic neutron scattering36,37,38,39,40, while the density fluctuations in water were detected by Nilsson and co-workers using small-angle X-ray scattering29,41.

Figure 3. Phonon density of states (PDOS) of ice from first-principles calculations.

The ordered hexagonal structure (ice-XI) is employed with the predicted volumes (per formula-unit) using the PBE functional59.

Figure 4. Linear thermal expansion coefficient (LTC) of ice-XI.

The solid line is from the present first-principles calculations using the PBE functional58, and the blue dots are experimental data by Rottger et al.20.

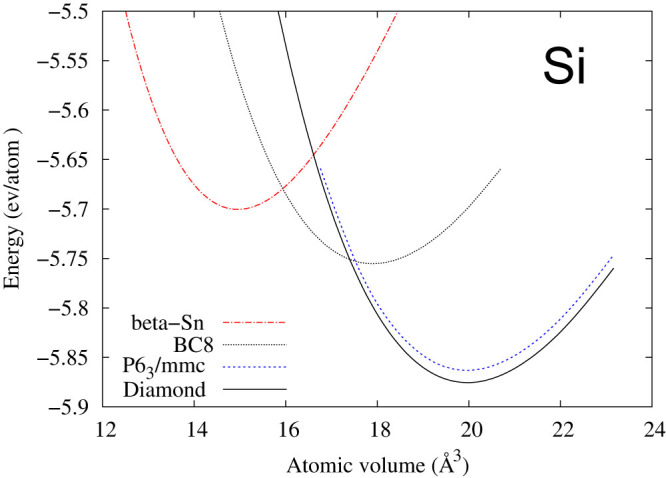

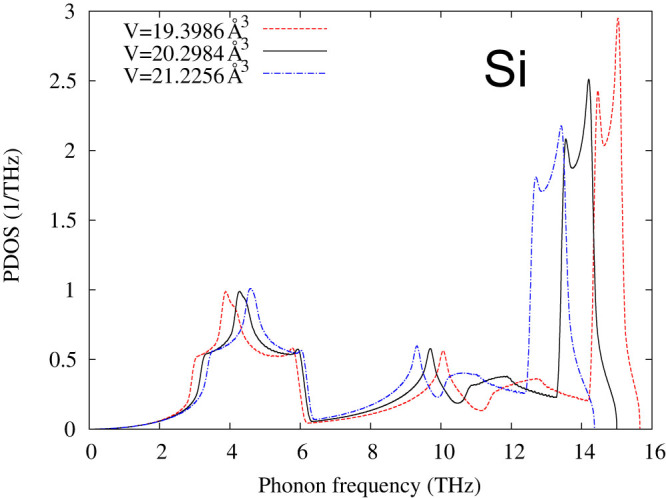

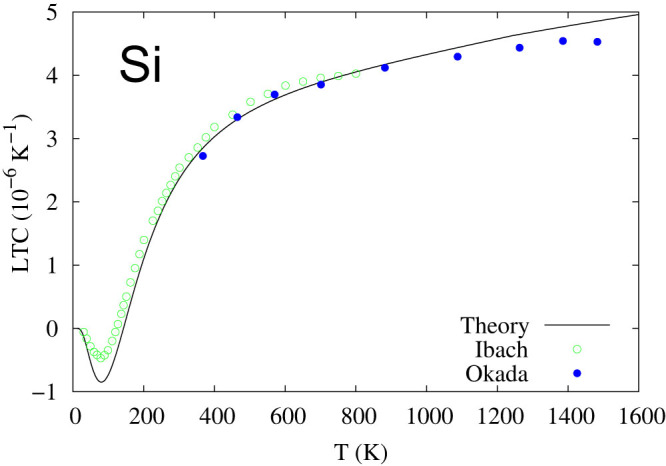

Furthermore, Fig. 5 depicts the total energies of four microstates of Si plotted with respect to volume. The energy difference between the diamond (Si-I) and P63/mmc (Si-IV) microstates at their respective minimums is extremely small, around 10 meV, which is equal to 2.418 THz. In comparison, the measured phonon energies of Si-I are in the range of 0–15 THz42. Therefore, one cannot obtain the phonon properties of pure Si-I or pure Si-IV individually in first-principles calculations since any local atomic perturbations in first-principles phonon calculations would result in some contributions from the other microstate and thus anomalies presented in the phonon spectrum curves. As shown in Fig. 6, the calculated phonon density of states for Si-I decreases with increasing volume at the low frequency range (<~5 THz). The experimental atomic volumes of Si-I and Si-IV are rather scattered as reviewed by Raffy et al.43. Both our DFT calculations and those by Raffy et al.43 show that Si-IV has smaller volume than Si-I, which are 19.9588 and 19.9739 Å3/atom in our calculations, respectively. Therefore, the existence of the metastable Si-IV microstate in the Si-I matrix results in a negative thermal expansion of Si-I both observed experimentally44,45 and predicted by phonon calculations as shown in Fig. 7. The more negative minimum value of the thermal expansion predicted by the first-principles phonon calculations is probably due to the use of the PBEsol exchange-correlation functional.

Figure 5. Total energies of Si in four structures from first-principles calculations at zero Kelvin using the PBEsol functional59.

Figure 6. Phonon density of states (PDOS) of Si-I (diamond structure) at three volumes from first-principles calculations.

Figure 7. Linear thermal expansion coefficient (LTC) of Si with the solid line from first-principles predictions and the symbols from experimental data44,45.

To account for other physical anomalies such as electromechanical (EM) and electrocaloric (EC) responses, the combined first and second laws of thermodynamics can be written as follows7,46

|

where U is the internal energy with its natural variables being entropy (S), strains (εij), electric displacements (Di), chemical components (Ni), and their conjugate quantities being temperature (T), six stresses (σij), three electric field components (Ei), and the chemical potential (μi). Using Ya and Xa to denote all potentials and molar quantities in the combined law and the Maxwell relation, anomalies such as EM and EC can be directly correlated to entropy and predicted using the approach presented in this work with the following general form

|

Anomalies of other physical properties such as thermal conductivity, shear modulus, and sound velocity can also be correlated to the phonon anomaly, which are being investigated. It may also provide insights on spatial, temperature, and composition dependence of spin distribution and expand beyond current phenomenological modeling47,48,49.

In summary, we show that thermal expansion is related to the pressure dependence of entropy. We introduce the concept of microstate configurational entropy, which statistically enables the description of the coexistence of metastable microstates with the stable microstate, evidenced by recent experiments with high resolutions in both time and space38,41,50. It is elucidated that the statistic interplay between stable and metastable microstates in a single phase can regulate its thermal expansion to be colossally positive, zero or negative. We demonstrate the predictions of NTE using an Invar alloy (Fe3Pt) and CPTE using an anti-Invar cerium and provide insights into the origin of the anharmonic vibrational modes and the thermal expansion anomalies of ice and silicon in terms of phonon anomaly. Our approach provides a theoretic foundation to understand and design materials with unique properties in terms of various anomalies such as thermal expansion, thermal conductivity, electrocaloric and electromechanical responses, and spin distributions38,46,48,51.

Methods

According to statistic mechanics, the partition function of a system is a sum of partition functions of individual microstates (Zi)52,

|

Under the constant temperature, pressure, and composition, the Gibbs free energy of the system is therefore obtained as

|

with

|

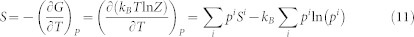

where Gi is the Gibbs free energy of the microstate i. The temperature and pressure derivatives of pi are obtained as

|

|

The entropy and volume thermal expansion of the system can be derived as follows

|

|

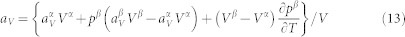

For a system of single phase with two microstates, one stable and one metastable, the volume thermal expansion is

|

For simplification, let us assume both microstates have similar thermal expansion, i.e.  , and equation (13) becomes

, and equation (13) becomes

|

From equation (14), one can see that it is the combination of volume difference and  that determines the thermal expansion. With

that determines the thermal expansion. With  , i.e. the stability of the β microstate increases with temperature, and setting aV = 0, one obtains

, i.e. the stability of the β microstate increases with temperature, and setting aV = 0, one obtains

|

With further increase of temperature, thus pβ, the thermal expansion becomes negative.

Phonon properties of a single microstate at zero K can be accurately predicted from first-principles calculations based on the density functional theory (DFT) through the supercell phonon method or the linear response theory53,54. In the present work, first-principles calculations for ice and silicon are accomplished within the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method55,56 as implemented in the VASP package (version 5.2)57. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)58 exchange-correlation functional is chosen for ice and the PBEsol exchange-correlation functional59 for silicon. The phonon calculations are performed within the small displacement approach using a supercell containing 288 atoms for ice and 128 atoms for silicon in terms of our mixed-space approach60,61. In the case of ice, the required Born effective charge and dielectric constant tensors by the mixed-space approach are calculated following the linear-response approach by Gajdoš et al.62. Thermal expansion coefficients are obtained following our previous works9,13,63.

Author Contributions

Z.K.L. proposed the idea. Y.W. performed first-principles calculations. S.L.S. organized the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript equally.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through Grant Nos. DMR-1006557, CHE-1230924, DMR-1310289, and CMMI-1333999. First-principles calculations were carried out partially on the LION clusters supported by the Materials Simulation Center and the Research Computing and Cyber infrastructure unit at the Pennsylvania State University, partially on the resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231, and partially on the resources of XSEDE supported by NSF with Grant No. ACI-1053575.

References

- Guillaume C. E. Invar and its applications - Preliminary. Nature 71, 134–139 (1904). [Google Scholar]

- Benedicks C. & Sederholm P. The anomalous dilatation of Invar. Nature 118, 842–842 (1926). [Google Scholar]

- Ernst G., Broholm C., Kowach G. R. & Ramirez A. P. Phonon density of states and negative thermal expansion in ZrW2O8. Nature 396, 147–149 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin A. L. et al. Colossal positive and negative thermal expansion in the framework material Ag3[Co(CN)6]. Science 319, 794–797 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolger C. Invar nickel-iron alloy: 100 years on. Mater. World 4, 332–333 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Li C. W. et al. Structural relationship between negative thermal expansion and quartic anharmonicity of cubic ScF3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 195504 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillert M. Phase Equilibria, Phase Diagrams and Phase Transformations, (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. K. First-principles calculations and CALPHAD modeling of thermodynamics. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 30, 517–534 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Thermodynamics of the Ce γ−α transition: Density-functional study. Phys. Rev. B 78, 104113 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Koskimaki D. C., Gschneidner Jr K. A. & Panousis N. T. Preparation of single-phase β and α cerium samples for low-temperature measurements. J. Cryst. Growth 22, 225–229 (1974). [Google Scholar]

- Schiwek A., Porsch F. & Holzapfel W. B. High temperature-high pressure structural studies of cerium. High Pressure Res. 22, 407–410 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Zachariasen W. H. & Ellinger F. H. Crystal-structures of cerium metal at high-pressure. Acta Crystallogr. A 33, 155–160 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Shang S. L., Zhang H., Chen L. Q. & Liu Z. K. Thermodynamic fluctuations in magnetic states: Fe3Pt as a prototype. Phil. Mag. Lett. 90, 851–859 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Sumiyama K., Shiga M., Morioka M. & Nakamura Y. Characteristic magnetovolume effects in Invar type Fe-Pt alloys. J. Phys. F- Met. Phys. 9, 1665–1677 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. K., Wang Y. & Shang S. L. Origin of negative thermal expansion phenomenon in solids. Scripta Mater. 65, 664–667 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Mary T. A., Evans J. S. O., Vogt T. & Sleight A. W. Negative thermal expansion from 0.3 to 1050 Kelvin in ZrW2O8. Science 272, 90–92 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. S. O. et al. Compressibility, phase transitions, and oxygen migration in zirconium tungstate, ZrW2O8. Science 275, 61–65 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora A., Sastry V., Sahu P. & Mary T. The pressure-amorphized state in zirconium tungstate: A precursor to decomposition. J. Phys.-Conden. Matter 16, 1025 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Laplaca S. & Post B. Thermal expansion of ice. Acta Crystallogr. 13, 503–505 (1960). [Google Scholar]

- Rottger K., Endriss A., Ihringer J., Doyle S. & Kuhs W. F. Lattice-constants and thermal-expansion of H2O and D2O ice Ih between 10 and 265 K. Acta Crystallogr. B 50, 644–648 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhelezny B. V. Crystallisation of supercooled water in capillaries. Russ. J. Phys. Chem.USSR 42, 950 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- Kell G. S. Density, thermal expansivity, and compressibility of liquid water from 0°C to 150°C - Correlations and tables for atmospheric-pressure and saturation reviewed and expressed on 1968 temperature scale. J. Chem. Eng. Data 20, 97–105 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H. Thermodynamic stability and negative thermal expansion of hexagonal and cubic ices. J. Chem. Phys. 108, 4887–4893 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft N. W. & Lekner J. Structure and resistivity of liquid metals. Phys. Rev. 145, 83–87 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld Y. & Ashcroft N. W. Theory of simple classical fluids - universality in the short-range structure. Phys. Rev. A 20, 1208–1235 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Errington J. R. & Debenedetti P. G. Relationship between structural order and the anomalies of liquid water. Nature 409, 318–321 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Palmer J. C., Panagiotopoulos A. Z. & Debenedetti P. G. Liquid-liquid transition in ST2 water. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 214505 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holten V., Palmer J. C., Poole P. H., Debenedetti P. G. & Anisimov M. A. Two-state thermodynamics of the ST2 model for supercooled water. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 104502 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. et al. The inhomogeneous structure of water at ambient conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 15214–15218 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Engineering ToolBox. Water – Thermal Properties, (Date of access: 28/09/2014). http://www.engineeringtoolbox.com [Google Scholar]

- Sprik M. & Klein M. L. A polarizable model for water using distributed charge sites. J. Chem. Phys. 89, 7556–7560 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- Poole P. H., Sciortino F., Essmann U. & Stanley H. E. Phase-behavior of metastable water. Nature 360, 324–328 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Mishima O. & Stanley H. E. The relationship between liquid, supercooled and glassy water. Nature 396, 329–335 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Petrenko V. F. & Whitworth R. W. Physics of Ice, (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- Hermann A., Ashcroft N. W. & Hoffmann R. High pressure ices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 745–750 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley M. E. Impact of intrinsic localized modes of atomic motion on materials properties. Acta Mater. 58, 2926–2935 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Manley M. E., Lynn J. W., Chen Y. & Lander G. H. Intrinsically localized mode in α-U as a precursor to a solid-state phase transition. Phys. Rev. B 77, 052301 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Manley M. E., Shapiro S., Li Q., Llobet A. & Hagen M. E. Lattice dynamical origin of peak thermoelectric performance in AgPbmSbTe2+m observed by inelastic neutron scattering. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 083722 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Manley M. E. et al. Intrinsic localized modes observed in the high-temperature vibrational spectrum of NaI. Phys. Rev. B 79, 134304 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Manley M. E. et al. Formation of a new dynamical mode in α-U observed by inelastic X-ray and neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 125501 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson A. & Pettersson L. G. M. Perspective on the structure of liquid water. Chem. Phys. 389, 1–34 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tubino R., Zerbi G. & Piseri L. Lattice-dynamics and spectroscopic properties by a valence force potential of diamondlike crystals - C, Si, Ge, and Sn. J. Chem. Phys. 56, 1022–1039 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- Raffy C., Furthmuller J. & Bechstedt F. Properties of hexagonal polytypes of group-IV elements from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 66, 075201 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Ibach H. Thermal expansion of silicon and zine oxide (I). Phys. Status Solidi 31, 625–634 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y. & Tokumaru Y. Precise determination of lattice-parameter and thermal-expansion coefficient of silicon between 300 K and 1500 K. J. Appl. Phys. 56, 314–320 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z. K., Li X. Y. & Zhang Q. M. Maximizing the number of coexisting phases near invariant critical points for giant electrocaloric and electromechanical responses in ferroelectrics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 082904 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S. A. et al. Spintronics: A spin-based electronics vision for the future. Science 294, 1488–1495 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaworski C. M. et al. Spin-seebeck effect: A phonon driven spin distribution. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 186601 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharony A., Birgeneau R. J., Coniglio A., Kastner M. A. & Stanley H. E. Magnetic phase-diagram and magnetic pairing in doped La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1330–1333 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley M. E. et al. Phonon localization drives polar nanoregions in a relaxor ferroelectric. Nat. Commun. 5, 3683 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L. D. et al. Ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric figure of merit in SnSe crystals. Nature 508, 373–377 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau L. D. & Lifshitz E. M. Statistical Physics, (Pergamon Press Ltd., Oxford, New York, 1980). [Google Scholar]

- Baroni S., de Gironcoli S., Dal Corso A. & Giannozzi P. Phonons and related crystal properties from density-functional perturbation theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 515–562 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- van de Walle A. & Ceder G. The effect of lattice vibrations on substitutional alloy thermodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 11–45 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Blöchl P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G. & Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G. & Furthmuller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P., Burke K. & Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P. et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 136406 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. A mixed-space approach to first-principles calculations of phonon frequencies for polar materials. J. Phys.-Condes. Matter 22, 202201 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Shang S. L., Liu Z. K. & Chen L. Q. Mixed-space approach for calculation of vibration-induced dipole-dipole interactions. Phys. Rev. B 85, 224303 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gajdoš M., Hummer K., Kresse G., Furthmüller J. & Bechstedt F. Linear optical properties in the projector-augmented wave methodology. Phys. Rev. B 73, 045112 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu Z. K. & Chen L. Q. Thermodynamic properties of Al, Ni, NiAl, and Ni3Al from first-principles calculations. Acta Mater. 52, 2665–2671 (2004). [Google Scholar]