Abstract

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cellular oxidant stress are considered inducers of carcinogenesis. However, the association of ROS with cancer is both complex and, at times, paradoxical. We assessed the effects of dihydromyricetin (DHM) on the induction of ROS accumulation and on the activation of the mitochondrial signaling pathway in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. The results indicated that DHM could reduce ROS accumulation in a concentration-dependent manner. Additionally, with increasing concentrations of DHM, the expression of proteins that participate in the cell apoptosis program increased in a concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, we found that a low dose of H2O2 (10 nM) could reverse DHM-induced cell apoptosis. We observed the following critical issues: first, the cellular redox balance is vital in DHM-induced apoptosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, and second, ROS could function as a redox-active signaling messenger to determine DHM-induced cell apoptosis. In this study, we demonstrated that low levels of ROS are also critical for the function of HCC cells.

Dihydromyricetin (DHM, C15H12O8, PubChem CID: 161557, Figure 1A) is a major active ingredient of flavonoid compounds and is a white needle-like crystal that can be extracted from Ampelopsis grossedentata. It exhibits potent antitumor activity against human tumors both in vivo and in vitro1. Many other pharmacological properties have been reported for DHM, such as anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, cough suppressant, antioxidant, antihypertensive, hepatoprotective and anticancer effects2,3. Recent studies have demonstrated that DHM is highly effective in counteracting acute ethanol intoxication4.

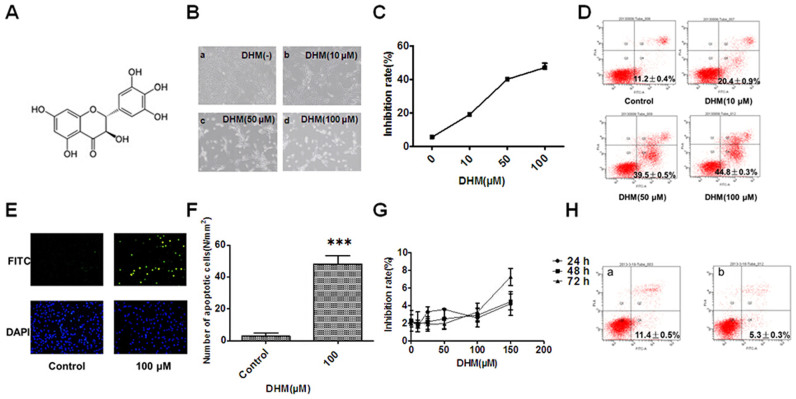

Figure 1. DHM inhibits cell proliferation and promotes cell apoptosis.

(A): The chemical structure of DHM. (B): DHM induces apoptosis in HepG2 cells at 24 h (a: control, b: 10 μM, c: 50 μM, d: 100 μM), which was visualized by microscopy (×100). (C): Cell growth, as detected by the MTT assay, was inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner at 24 h after DHM treatment. (D): DHM-induced cell apoptosis was analyzed by flow cytometry (24 h). (E): DHM-induced cell apoptosis (100 μM, DNA fragmentation) was visualized by fluorescence microscopy (24 h, TUNEL staining, original magnification: ×100). (F): Number of apoptotic cells. At least six 12 mm2 fields of view were counted in each culture dish. (G): DHM did not inhibit cell proliferation in normal hepatic HL7702 cells. Cell growth was detected by the MTT assay. H: HL7702 cells were treated with 100 μM DHM for 24 h, and cell apoptosis was analyzed using flow cytometry (a: Control, b: 100 μM DHM). Values are the means ± SD for at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

The implications of reactive oxygen species (ROS) regulation are highly significant for cancer therapy because ordinary antitumor drugs inhibit cancer cell proliferation through an increase in ROS. Previous studies have reported that DHM can significantly inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells5. In the present study, DHM abolished ROS and glutathione (GSH) production and activated caspase-9 protein in HepG2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner, which promoted cellular apoptosis. In addition, a low dose of H2O2 (10 nM) could reverse DHM-induced cell apoptosis. We demonstrated that the balance between ROS production and antioxidants plays a vital role in DHM-induced cell apoptosis.

Methods

Drugs and reagents

DHM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 100% DMSO to prepare a 50 mM stock solution and was stored at −20°C. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1% throughout the study. N-acetylcysteine (NAC; Sigma) was dissolved in PBS to yield a final concentration of 50 mM. Antibodies against HO-1, caspase-9, caspase-8, caspase-3, PARP, Cyt c, Bax, Bcl-2, BAK and β-actin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (EarthOx, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used as a secondary antibody.

Cell culture and DHM treatment

Human hepatoma HepG2 and HL7702 cells were donated by the Clinical Research Center of the Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical College (Zhanjiang, China). HepG2 and HL7702 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium and DMEM, respectively, and were supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (GIBCO, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 U/ml). The cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air + 5% CO2 at 37°C. HepG2 cells were grown in standard media, and when the confluence reached 70–80%, the cells were treated with different concentrations of DHM (10, 50, or 100 μM) for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. H2O2 (0, 2, 5, 10, or 50 nM) was dissolved in the medium of cells treated with 100 μM DHM for 24 h. NAC (1 mM) was dissolved in the medium of HepG2 cells treated with 50 μM DHM. HL7702 cells were grown in standard media, and when the confluence reached 70–80%, they were treated with different concentrations of DHM (0, 5, 10, 25, 50,100 or 150 μM) for 24 h, 48 h and 72 h.

Subcellular fractionation

Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions of cells were prepared using a mitochondria/cytosol fractionation kit purchased from BioVision Inc. (Mountain View, CA, USA). Briefly, the cells were treated with different concentrations of DHM (0, 10, 50 or 100 μM) for 24 h and were then harvested with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, the cells were lysed in 400 μL of extraction buffer containing dithiothreitol and protease inhibitor cocktail on ice for 30 min with homogenization using a Kontes Dounce tissue grinder (Fisher, CA, USA). After 10 min of centrifugation (700 × g), the supernatant was centrifuged at 1200 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was collected, and the pellets were resuspended in the mitochondrial extraction buffer (mitochondrial fraction). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared using a nuclear/cytosol fractionation kit purchased from BioVision Inc. according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of the intracellular level of ROS

A ROS assay kit (BioVision) was used to detect the accumulation of intracellular ROS in HepG2 cells. Briefly, cells were treated with different concentrations of DHM (0, 10, 50 or 100 μM) for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h and were subsequently cultured with or without 10 nM H2O2 for 24 h. After removing the medium containing 100 μM DHM, 100 μL of DCFDA mix containing 2.5 × 104 cells was added to each well and incubated for 45 min at 37°C in the dark. Blank wells (with non-stained cells) were also used as a control. The fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (EnSpire™ 2300 Multilabel Reader, PE) at Ex/Em. = 488/525 nm.

Measurement of intracellular GSH levels

The intracellular level of GSH was determined using an ApoGSH glutathione detection kit (BioVision) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after treating cells with different concentrations of DHM (0, 10, 50 or 100 μM) for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h, 1 × 106 cells were harvested and centrifuged at 700 × g for 5 min. The cells were then lysed in 100 μL of ice-cold lysis buffer on ice for 10 min and centrifuged at 1200 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then analyzed with the glutathione detection kit. The fluorescence was measured using a fluorescence plate reader (EnSpire™ 2300 Multilabel Reader, PE) at Ex/Em. = 380/460 nm.

Measurement of ATP production

The intracellular level of ATP was measured using an ApoSENSOR cell viability assay kit (BioVision) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were treated with DHM (10, 50 or 100 μM) for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. Subsequently, 104 cells were incubated with 100 μL of nuclear releasing reagent for 5 min at room temperature with gentle shaking, followed by further incubation with 4 μL of ATP monitoring enzyme. Detection was performed using a luminometer (Berthold Sirius L, Germany).

Annexin V/PI double staining assay

Apoptotic cells were quantified using an Annexin V-FITC/PI kit (BioVision), detected by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson), and analyzed with Modfit and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Briefly, NAC (1 mM) was dissolved in the medium of HepG2 cells treated with 50 μM DHM. HL7702 cells were treated with 100 μM DHM for 24 h. HepG2 cells were either pretreated with 50, 100 and 150 μM DHM and subsequently incubated with 1 mM NAC or pretreated with 50 μM DHM and subsequently incubated with 10 nM H2O2. Experiments were performed for 24 h or 12 h. Then, the cells were collected and resuspended in binding buffer (pH 7.5, 10 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 140 mM NaCl) and incubated with Annexin V-FITC and PI for 10 min in the dark prior to flow cytometric analysis. Cells that were in early stages of apoptosis were Annexin V-positive, whereas Annexin V and PI double-positive cells were considered to be in the late stages of apoptosis.

TUNEL staining assay

Apoptotic cells were detected using a DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System kit (Promega, USA.). Briefly, cell densities were adjusted to 2 × 104 cells per 100 μL. The cells were seeded into a 96-well plate, which was kept in an incubator overnight to allow for attachment and recovery, pretreated with 100 μM DHM for 24 h and washed twice. The cells were then fixed in freshly prepared 4% methanol-free formaldehyde solution in PBS (pH 7.4) for 25 min at 4°C, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton® X-100 solution in PBS for 5 min and stained with 40 mL of DAPI solution for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. The samples were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope (OLYMPUS, IX70, Japan) equipped with a standard fluorescein filter set to view green fluorescence at 520 ± 20 nm and blue fluorescence (for DAPI) at 460 nm.

MTT assay

HepG2 and HL7702 cell densities were adjusted to 2 × 104 cells per 100 μL. The cells were seeded into a 96-well plate, which was kept in an incubator overnight to allow for attachment and recovery. HepG2 cells were pretreated with 10, 50 or 100 μM DHM for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. HL7702 cells were pretreated with 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 or 150 μM DHM for 24 h, 48 h or 72 h. HepG2 cells were pretreated with 50 μM DHM and subsequently treated with H2O2 (2, 5, 10, 50 or 100 nM) for 24 h. MTT was dissolved in warm assay medium to a concentration of 5 mg/mL. A total of 20 μL of MTT solution was transferred to each well to yield a final volume of 120 μL/well. The plates were incubated for 4 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. Then, the supernatants were removed, and 100 μL of DMSO was added to ensure total solubility of the formazan crystals. After 15 min of shaking, the absorbance was measured at 490 nm using a plate reader (Perkin–Elmer, Waltham, USA). The inhibition ratio (%) was calculated using the following equation:

Inhibition ratio (100%) = [1- OD 490 (DHM-treated cells)/OD 490 (Control)] × 100%

Analysis of DHM-regulated apoptotic proteins

Cells were collected after treatment and were then lysed in lysis buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 4% (m/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 200 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonylfluoride, and 1 μg/mL aprotinin) for 30 min on ice. The lysate was separated by centrifugation at 4°C for 15 min at 1200 × g. The total protein concentration in the supernatant was detected using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, Jiangsu, China). SDS-PAGE was performed with an 8–15% gradient or with standard polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were saturated with 5% milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline and 1% Tween 20) and incubated with primary antibodies in diluent overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP secondary antibody for 1 h, followed by four washes with TBST. Detection was performed using an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Inc., NE).

Cells were incubated for 6 h with or without DHM. All floating and attached cells were harvested, fixed with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and washed with ice-cold PBS. Then, the cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100, washed with ice-cold PBS, stained with antibodies against Cyt c and AIF and subsequently incubated with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, California, USA). After the cell nuclei were stained with DAPI, the cells were observed using a fluorescence microscope (CS SP5II, Germany) with peak excitation wavelengths of 555 nm, 645 nm and 460 nm.

Statistical analysis

All results shown represent the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments performed in a parallel manner unless otherwise indicated. The results were evaluated using Student's t-test, and differences were considered significant at the *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 or **P < 0.001 level. All figures shown in this paper are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Results

DHM inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in HepG2 cells

Untreated HepG2 cells grew well, whereas the cells treated with DHM for 24 h were distorted in shape, and most became round (Figure 1B); in addition, the number of sloughed cells increased in a concentration-dependent manner. An MTT assay was used to evaluate the inhibitory effects of DHM on HepG2 cells. DHM treatment of HepG2 cells resulted in significant concentration-dependent inhibition of cell growth at 24 h (Figure 1C). These data revealed that DHM strongly reduced the viability of HepG2 cells, which may contribute to its antitumor potency. Cells that were treated with 50 μM DHM were distorted in shape and floated in the medium; cell growth was inhibited, and most HepG2 cells underwent apoptosis. The apoptosis occurred in a concentration-dependent manner for 24 h (Figure 1D). TUNEL staining was used to detect cell death, and the results showed that the amount of DNA fragmentation in cells that were treated with 100 μM DHM was much higher than that in vehicle-treated cells at 24 h (Figure 1E and F); this was evidenced by an increase in green fluorescence. These results demonstrated that DHM could significantly inhibit proliferation and could promote apoptosis of HepG2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. By contrast, the normal hepatic HL7702 cell line was not sensitive to DHM (Figure 1G and H).

DHM sharply reduces ROS production in HepG2 cells

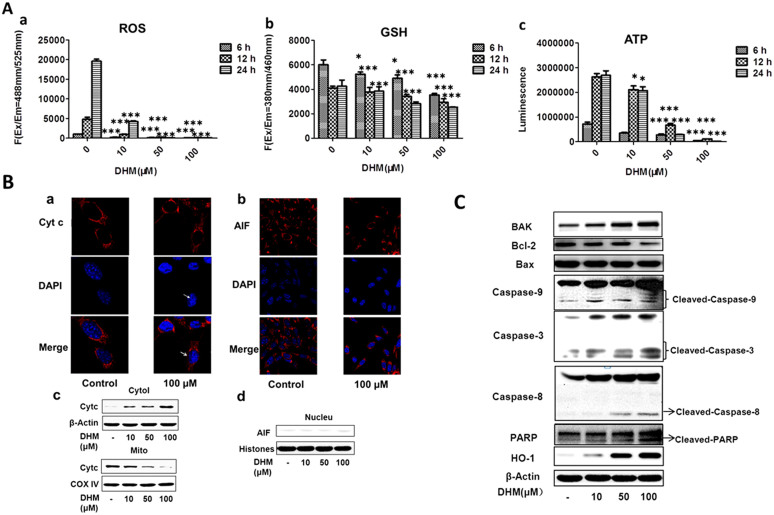

We measured the ROS level in HepG2 cells that were treated with various concentrations of DHM for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. The cellular oxidation of H2DCFDA, which is oxidized to green fluorescent DCF by various peroxide-like ROS and by nitric oxide-derived reactive intermediates, was used as a probe. The data demonstrated that DHM could significantly decrease the production of ROS to a very low level in HepG2 cells and that the imbalance of ROS may promote mitochondrial dysfunction and trigger mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. The intracellular levels of ROS in cells treated with 10, 50 and 100 μM DHM decreased in a concentration-dependent manner compared with the levels in vehicle-treated cells (Figure 2A-a).

Figure 2. DHM reduced ROS, GSH and ATP production in HepG2 cells, and DHM regulated apoptotic proteins in HepG2 cells in a concentration- dependent manner.

(A): Cells were treated with DHM (10, 50 and 100 μM) for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h, and then intracellular levels of ROS (a), GSH (b) and ATP (c) were detected. The intracellular levels of ROS, GSH and ATP in DHM-treated cells were markedly decreased compared with their levels in the vehicle control. (B): The cells were immunostained with anti-Cyt c (a) and anti-AIF (b) together with DAPI nuclear staining. Cells were treated with 100 μM DHM for 6 h and were visualized using confocal microscopy. (c): Cyt c protein expression in the mitochondria and cytosol; the release of Cyt c from the mitochondria to the cytosol is illustrated. (d): AIF protein was not detected in the nucleus. (C): Cells were treated with DHM (10, 50 and 100 μM) for 24 h, and the levels of PARP, caspase-9, caspase-3, caspase-8, HO-1, Bcl-2, BAK and Bax proteins were detected by western blotting in HepG2 cells. The data showed that DHM regulates apoptotic proteins in HepG2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner. All images are representative of three independent experiments. Values are the means ± SD for at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 indicate significant differences between the experimental and control groups.

DHM markedly reduces the level of GSH in HepG2 cells

We used monochlorobimane (MCB) dye to detect the levels of GSH in HepG2 cells that were treated with various concentrations of DHM for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. The unbound form of MCB is almost non-fluorescent, whereas it fluoresces blue (Ex/Em. = 380/460 nm) when bound to GSH. The data revealed that DHM could significantly decrease the production of GSH in HepG2 cells, which may promote mitochondrial dysfunction and trigger mitochondria-mediated apoptosis. Intracellular levels of GSH in cells treated with 10, 50 and 100 μM DHM decreased in a concentration-dependent manner compared with the levels in vehicle-treated cells (Figure 2A-b).

DHM reduces the intracellular level of ATP in HepG2 cells

To evaluate the dysfunction in mitochondrial energy production, we detected the intracellular levels of ATP in DHM-treated cells. Cells were treated with various concentrations of DHM for 6 h, 12 h and 24 h, and the data indicated that the intracellular levels of ATP dramatically decreased in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2A-c).

DHM regulates the production of apoptotic proteins

The loss of ROS induces cell apoptosis through the release of proapoptotic proteins such as Cyt c, which are released from the mitochondria into the cytosol6. In the present study, cells were treated with 100 μM DHM for 6 h, and it was found that Cyt c was released from the mitochondria into the cytosol (white arrow) (Figure 2B-a, c), whereas AIF was not detected in the nucleus (Figure 2B-b, d). Cyt c can activate caspase-9, which in turn activates caspase-3 via the induction of cleavage. Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP), an important substrate of caspase-3, can then be cleaved. In the present study, cells were treated with different concentrations of DHM for 24 h. Increases in activated caspase-9, caspase-8 and caspase-3 were observed. The results showed that the expression of caspase-9 and caspase-3 were increased and that the levels of cleaved PARP were elevated in DHM-treated HepG2 cells compared with controls. The oxidative stress-related protein HO-1 and BAK were increased whereas Bcl-2 was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner; however, no changes were observed in the levels of Bax (Figure 2C).

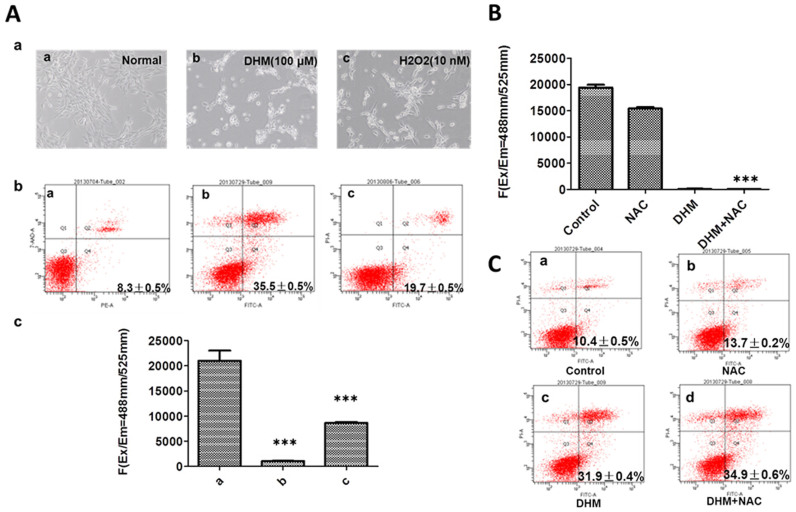

A low dose of H2O2 reversed DHM-induced cell apoptosis

To confirm whether cells that were treated with DHM could be rescued with H2O2, HepG2 cells were co-cultured with 100 μΜ DHM and H2O2 (2, 5, 10, 50 and 100 nM) for 24 h. We found that very few HepG2 cells that were co-cultured with 100 μΜ DHM and 10 nM H2O2 underwent apoptosis. (The data did not shown). In HepG2 cells that were treated with 100 μΜ DHM for 24 h and cultured with fresh culture medium containing 10 nM H2O2, it was observed that minimal cell apoptosis was observed, and normal cell growth was recovered 24 h after DHM withdrawal (Figure 3A-a). An annexin V/PI double-staining assay was used to evaluate the apoptotic activity of HepG2 cells. This assay demonstrated that the rate of apoptosis of cells treated with 10 nM H2O2 was decreased compared with that of cells treated with vehicle (Figure 3A-b). A micro-dose of H2O2 could reverse DHM-induced cell apoptosis, and the production of ROS was reduced 24 h after DHM withdrawal; however, ROS production recovered to a greater extent with a micro-dose of H2O2 (Figure 3A-c).

Figure 3. A low dose of H2O2 reversed DHM-induced apoptosis, whereas NAC aggravated DHM-induced apoptosis.

(A): a: DHM-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells with or without H2O2 (a: normal HepG2 cells, b: HepG2 cells cultured for 24 h after withdrawal of 100 μM DHM, c: HepG2 cells cultured with 10 nM H2O2 for 24 h after withdrawal of 100 μM DHM). The cells were visualized by microscopy ( 100). b: Apoptosis was analyzed according to flow cytometry distributions (a: normal HepG2 cells, b: HepG2 cells cultured for 24 h after withdrawal of 100 μM DHM, c: HepG2 cells cultured with 10 nM H2O2 for 24 h after withdrawal of 100 μM DHM). c: ROS production was measured for the treatment described in b. B: Cells were pretreated with 1 mM NAC for 1 h and subsequently treated with or without 50 μM DHM for 24 h; intracellular ROS levels were then measured. The intracellular levels of ROS decreased in the DHM-NAC-treated cells compared with the NAC-treated cells. C: Apoptosis was analyzed according to the flow cytometry distributions for the treatments in B (a: normal HepG2 cells, b: NAC pretreatment, c: DHM without NAC pretreatment, d: DHM with NAC pretreatment). The values are the means ± SD for at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

NAC exacerbates DHM-mediated ROS reduction in HepG2 cells

To illustrate the role of ROS in DHM-induced apoptosis, HepG2 cells were treated with DHM in the presence or absence of the antioxidant NAC. The results showed that NAC exacerbated the DHM-mediated reduction of ROS and induced more apoptosis in HepG2 cells (Figure 3B, C).

Discussion

In the present study, our results showed that DHM could induce apoptosis in HepG2 cells. As the concentration of the drug increased, cell proliferation decreased, and the rate of apoptosis increased. However, DHM did not inhibit cell growth in normal hepatic HL7702 cells. Historically, ROS have been considered to lack specific functions beyond causing cell damage and physiological dysfunction. The accumulation of ROS has been linked to multiple pathologies, including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and premature aging7. Previous studies have considered that ROS are a “by-product” of cellular aerobic metabolism and cytotoxicity. However, recent studies suggest that low levels of ROS could function as redox-active signaling messengers to promote the proliferation and differentiation of cells. Thus, intracellular ROS may not be a “by-product” but rather an important class of signaling molecules involved in multiple signaling pathways for cellular proliferation and differentiation8,9,10,11. The demand for ROS in cancer cells is higher than that in normal cells. If the content of ROS is lower than the minimum requirement for a cellular response, cancer cells would not grow normally12. In this study, we confirmed that a sharp decline in the production of ROS could significantly inhibit cell proliferation and induce apoptosis of HepG2 cells.

Many chemical and physiological phenomena that are capable of inducing apoptosis are known to provoke oxidative stress via the generation of ROS, which suggests a close relationship between oxidative stress and apoptosis13,14. H2O2 may directly induce apoptosis, whereas antioxidants could block this effect15. In the present study, we found that treatment with DHM significantly induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells; however, apoptosis could be reversed with a low dose of H2O2. These results suggest that the balance between ROS production and antioxidants could regulate DHM-induced early and late apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Our results indicated that the balance between ROS production and various antioxidants was very important for the growth of cancer cells. DHM sharply reduced the production of ROS in HepG2 cells, which might have disrupted the balance of redox reactions. This disruption occurred in a concentration-dependent manner. DHM thus disturbed the cells' internal balance and blocked ROS-mediated signal transduction to induce tumor cell apoptosis. However, its mechanism of action has not been clearly defined.

In recent years, the term “redox state” has not only been used to describe a physiologically balanced redox state, such as GSSG/GSH, but has also been used to describe a general cellular oxidation/reduction environment16. Under normal conditions, a cell's redox state is maintained within a narrow range similar to the manner in which a biological system regulates its pH. Under pathological conditions, the redox state can be altered to lower or higher values17. Low GSH levels are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and cell apoptosis, which could reduce the chemoresistance of tumors18. Our data indicated that DHM significantly reduced the production of GSH in HepG2 cells. Moreover, ATP acts as a direct energy source for cellular metabolism, and the amount of ATP might be directly influenced by the process of apoptosis. As cells proliferate, intracellular ROS, ATP and GSH are also gradually increased (Figure 2A-a, b, c). Our results showed that DHM dramatically decreased the level of GSH and the generation of ATP in a concentration-dependent manner. Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is a widespread and redox-sensitive enzyme that catabolizes heme to carbon monoxide (CO), iron, and biliverdin. A battery of redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as activator protein-1 (AP-1), nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and nuclear factor E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2), and their upstream kinases, including mitogen-activated protein kinases, play an important regulatory role in HO-1 gene induction19. In many tissues and in various mammalian species, the induction of HO-1 mRNA has served as a useful marker of cellular oxidative stress20. HO-1 is usually expressed at low levels under normal conditions, but it is highly induced in response to various reagents that cause oxidative stress, including ultraviolet irradiation, hydrogen peroxide, heavy metals, and lack of oxygen. HO-1 has been assumed to play a role in the induction of chemotherapeutic protective mechanisms21,22. Our results also demonstrated that up-regulation of HO-1 expression induced by DHM could lead to apoptosis in HepG2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner.

We performed immunofluorescence and western blot analysis of cytochrome c and AIF in HepG2 cells. Our findings provide a paradigm for mitochondria-dependent cell death pathways that involve a postmitochondrial level of pharmacological and possibly endogenous regulation that precedes the intracytosolic release of the caspase-independent death effector AIF. We did not observe AIF production in the nucleus, but we found that Cyt c released from mitochondria exerted its apoptogenic effects in the cytosol through its role in caspase-8 and caspase-9 activation. As a substrate of caspase-9, PARP is involved in repairing DNA damage. During apoptosis, the activation of caspase-9 is a crucial step in apoptotic cell death23,24,25 because it induces PARP cleavage. PARP is proposed to be important in the control of many cellular processes, such as DNA repair, cell death, chromatin function and maintenance of genome stability26. PARP activation is an early DNA damage response indicator. Previous studies have demonstrated that cell survival is maintained if Bcl-2 and Bax are balanced and that a higher Bcl-2 expression level leads to inhibition of apoptosis27,28. In this study, we confirmed that DHM could elevate the levels of caspase-9 and cleaved PARP proteins in the HepG2 cell line, whereas the levels of PARP and Bcl-2 proteins decreased. However, DHM had no effect on the release of AIF. These data suggest that the loss of ROS-mediated signaling may promote apoptosis in human hepatoma cells.

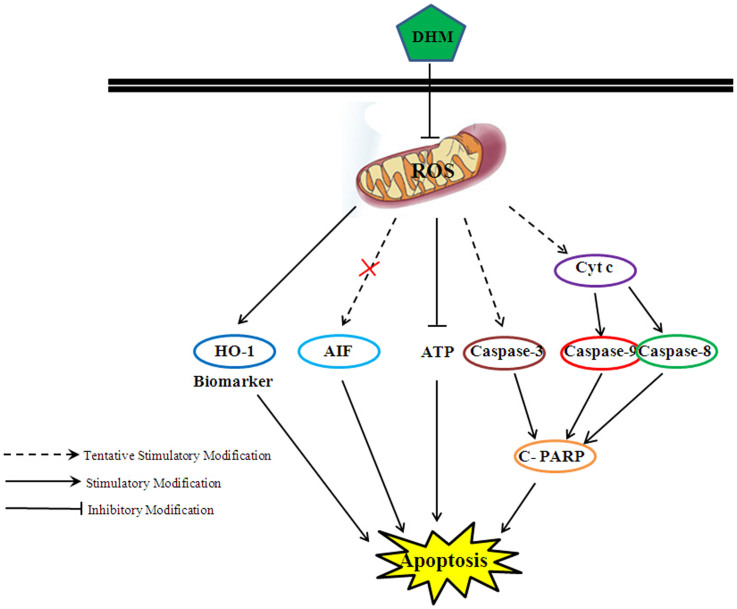

The main ROS species are superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, both of which are redox signaling molecules in the context of various cellular functions. Redox imbalance due to excessive or insufficient ROS is an induction factor for the pathogenesis of disease, including cancer development and progression. We confirmed that ROS is significantly associated with cell growth and that loss of ROS could trigger activation of caspase-9 and cleavage of PARP, leading to apoptosis. In this study, we found that apoptosis that was induced by DHM could be reversed by a small amount of accumulated ROS. We confirmed that cellular redox balance plays a vital role in carcinogenesis. We consider the formation of ROS to be a requisite and beneficial event for cancer cell growth, and we hypothesize that an imbalance in redox reactions could result in tumor cell death (Figure 4). Although future investigations should be conducted to demonstrate the molecular mechanism underlying the DHM-induced reduction of ROS generation, our data indicated that DHM-induced apoptosis may act, at least partially, through a ROS-related pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells.

Figure 4. Cellular pathway of DHM-induced cell apoptosis in HepG2 cells.

DHM induced HepG2 cell apoptosis via the activation of Cyt c, caspase-9 and PARP; moreover, the production of ROS decreased, which eventually led to apoptosis.

Author Contributions

R.Z.Z. wrote the article. B.L. and X.Y.T. performed the experiments. J.L. (The third author), S.X.W., J.L. and Q.Y.Z. prepared Figures 1–4. B.L. participated in data and statistical analyses. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the following grants: Guangdong medical college scientific research fund (No. Q2012033, M2013012 and M2013024), China; The second batch of 2013 Zhanjiang financial special backup project of science and technology (No. 10). This work was also supported by the Institute of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical College. We thank Dr. Du Feng, Wen Li, Wenxian Wu, Weili Tian, and Xingli Zhang.

References

- Li H. et al. Comparison of refluxing, ultrasonic- and microwave-assisted extraction of dihydromyricetin from Ampelopsis grossedentata. J AOAC Int 91, 1278–1283 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J., Guan Y., Zeng S. & Liu D. Ampelopsin prevents apoptosis induced by H2O2 in MT-4 lymphocytes. Planta Med 74, 252 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundaković T. et al. Cytotoxic, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of Ampelopsis brevipedunculata and Parthenocissus tricuspidata (Vitaceae). Arch Biol Sci 60, 641–647 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y. et al. Dihydromyricetin as a novel anti-alcohol intoxication medication. J Neurosci 32, 390–401 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa V. et al. Oxidative stress and cancer: An overview. Ageing Res Rev 12, 376–390, 10.1016/j.arr.2012.10.004 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Circu M. L. & Aw T. Y. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radical Bio Med 48, 749–762 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sena L. A. & Chandel N. S. Physiological roles of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Mol cell 48, 158–167, 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.025 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R., Wang Y., Zhang L. & Guo Q. Oxidative stress and liver disease. Hepatol Res: the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology 42, 741–749, 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2012.00996.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerling B. M. et al. Hypoxic activation of AMPK is dependent on mitochondrial ROS but independent of an increase in AMP/ATP ratio. Free Radical Bio Med 46, 1386–1391 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Garcia D., Wood C. D., Castro-Obregon S. & Covarrubias L. Reactive oxygen species: A radical role in development? Free Radical Bio Med 49, 130–143, 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.03.020 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A. Q., Nafees S. & Sultana S. Perillyl alcohol protects against ethanol induced acute liver injury in Wistar rats by inhibiting oxidative stress, NFkappa-B activation and proinflammatory cytokine production. Toxicology 279, 108–114, 10.1016/j.tox.2010.09.017 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trachootham D., Alexandre J. & Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov 8, 579–591 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak N. & Khandelwal S. Oxidative stress and apoptotic changes in murine splenocytes exposed to cadmium. Toxicology 220, 26–36 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B. & Gutteridge J. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: an overview. Method Enzymol 186, 1–85 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. et al. Heat shock transcription factor-1 inhibits H2O2-induced apoptosis via down-regulation of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. Mol Cell Bio 347, 21–28 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohé L. Glutathione Peroxidases. Selenoproteins and Mimics, 1–25 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Buonocore G., Perrone S. & Tataranno M. L. in Semin in Fetal Neonat M. 186–190 (Elsevier). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie F. et al. Reactive oxygen species accumulation contributes to gambogic acid-induced apoptosis in human hepatoma SMMC-7721 cells. Toxicology 260, 60–67 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi L. et al. Heme regulatory motifs in heme oxygenase-2 form a thiol/disulfide redox switch that responds to the cellular redox state. J Bio Chem 284, 20556–20561 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J. T. et al. Ionizing radiation activates the Nrf2 antioxidant response. Cancer Res 70, 8886–8895 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton P. A., Goodwill A. G., James M. E., Brock R. W. & Frisbee J. C. Hypercholesterolemia and microvascular dysfunction: interventional strategies. J Inflammation 7, 54 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares M. P. & Bach F. H. Heme oxygenase-1: from biology to therapeutic potential. Trends Mol Med 15, 50–58 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan L. A. & Clarke P. R. Apoptosis and autophagy: Regulation of caspase-9 by phosphorylation. FEBS J 276, 6063–6073 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratton S. B. & Salvesen G. S. Regulation of the Apaf-1–caspase-9 apoptosome. J Cell Sci 123, 3209–3214 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda Y., Saito M., Yamamura T., Yaguchi T. & Nishizaki T. Extracellular adenosine induces apoptosis in Caco-2 human colonic cancer cells by activating caspase-9/-3 via A 2a adenosine receptors. J Gastroenterology 44, 56–65 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peralta-Leal A. et al. PARP inhibitors: new partners in the therapy of cancer and inflammatory diseases. Free Radical Bio Med 47, 13–26, 10.1016/j. freeradbiomed.2009.04.008 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoor N. H. 7 alpha-Hydroxy-beta-Sitosterol from Chisocheton tomentosus Induces Apoptosis via Dysregulation of Cellular Bax/Bcl-2 Ratio and Cell Cycle Arrest by Downregulating ERK1/2 Activation. Evid-Based Compl Alt 2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Poeta G. et al. The genotype nucleophosmin mutated and FLT3-ITD negative is characterized by high bax/bcl-2 ratio and favourable outcome in acute myeloid leukaemia. Brit J Haematol 149, 383–387 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]