Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association of the failure of porcelain laminate veneers with factors related to the patient, material, and operator.

Methods

This clinical survey involved 29 patients (19 women and 10 men) and their dentists, including undergraduate and postgraduate dental students and dental interns. Two questionnaires were distributed to collect information from participants. All patients were clinically examined. Criteria for failure of the porcelain laminate veneers included color change, cracking, fracture, and/or debonding.

Results

A total of 205 porcelain laminate veneers were evaluated. All of the restorations were fabricated from IPS e.max Press and cemented with Variolink Veneer (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Principality of Liechtenstein) or RelyX veneer cement (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA). The preparations were generally located in enamel (58.6%), and most veneers had an overlapped design (89.7%). Ten patients (34.48%) showed veneer failure, most often in terms of color change (60%). Overall, 82.8% of patients were satisfied with their restorations.

Conclusion

Insufficient clinical skills or operator experience resulted in restoration failure in one-third of patients.

Keywords: Color change, Debonding, Overlapped design, Porcelain laminate veneer, Sensitivity, Window design

1. Introduction

The demand for treating unaesthetic anterior teeth continues to grow. Available options to restore their aesthetics include conservative treatments, such as bleaching and direct composite laminate veneers (Shillingburg et al., 1997), and reliable but aggressive treatments, such as full crown restorations (Peumans et al., 2000; Strassler, 2007). However, crown preparations are associated with some problems, including the extensive removal of the sound tooth structure and irreversible effects on the dental pulp (Peumans et al., 2000).

Calamia (1984) first described the treatment of porcelain with hydrofluoric acid and silane to create an adhesive interface, which serves as the basis for porcelain laminate veneers (Strassler, 2007). These tooth-colored materials can improve the aesthetic outcome of anterior restorations (Roberson et al., 2006). Improvements in adhesive systems and the development of new-generation porcelain technology have supported the growing demand for treating unaesthetic teeth with porcelain laminate veneers (Christensen, 2008). Studies have shown a 7% failure rate of porcelain laminate veneers, but failure had no direct impact on the clinical success in terms of longevity or durability (Friedman, 1998; Peumans et al., 2000). These restorations are highly esthetic, biocompatible, and resistant to staining and wear (Goldstein and Haywood, 1998).

Porcelain laminate veneer preparation can be a stressful for dentists with insufficient clinical skills or experience. Lack of good procedural knowledge frequently results in failed restorations. Several longitudinal clinical studies have been performed on the performance of porcelain laminate veneers placed by general practitioners or specialists, revealing acceptable results regardless of the type of failure and/or veneer design (Beier et al., 2012; Castelnuovo et al., 2000; Dumfahrt and Schäffer, 2000; Mizrahi, 2007). An evaluation of the clinical performance of veneers placed by undergraduate students in Ireland also revealed satisfactory restorations (Murphy et al., 2005). However, no studies have been performed in Saudi Arabia regarding the performance of porcelain laminate veneers placed by dentists at any level. Case unavailability, the need for time-consuming continuous and close supervision by clinical instructors, and procedural difficulty for students may explain the lack of such reports. The aim of this study was to investigate the association of the failure of porcelain laminate veneers with factors related to the patient, material, and operator.

2. Materials and methods

A clinical survey was conducted at the Riyadh Colleges of Dentistry and Pharmacy, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The study involved 29 patients (19 women and 10 men) and their dentists (undergraduate and postgraduate dental students and dental interns), who were selected from a convenience sample in which the dentists may have seen more than one patient. Participation was voluntary, all information was confidential, and the patients gave their written informed consent for clinical examination. The study design was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Two questionnaires were distributed to collect information from participants. The patient-specific questionnaire comprised 10 main questions, including eight close-ended and two open-ended questions regarding age, gender, color change, sensitivity before and after treatment, satisfaction with the restoration, and habits (e.g., bruxism, nail biting, and pen biting). They were also asked about their smoking status and whether they consumed coffee, tea, and/or soft drinks. The dentist-specific questionnaire comprised five close-ended and three open-ended questions about the time for porcelain laminate veneer cementation, indications, veneer design, preparation depth, placement of the finish line, impression technique and material, and type of temporary restoration and cement used.

All patients underwent a clinical examination to determine pulp vitality, sensitivity, structural defects (e.g., cracks, fracture, and debonding), color change, marginal pigmentation and adaptation, and suitability of the veneer design. The periodontal status was assessed by the gingival and plaque indices of Loe and Silness (Newman et al., 2001), and gingival recession was measured (in mm). Periapical and bitewing radiographs were used to check the presence of recurrent caries. Photographs were taken during the clinical examination, and pretreatment and posttreatment photographs were obtained from the dentists.

The criteria for failure of porcelain laminate veneers were color change, cracking, fracture, and/or debonding. Descriptive statistics were obtained for data analysis. The chi-square test or proportional t-test was used for statistical analysis at a significance level of 5% (P < 0.05). The data were analyzed by using IBM SPSS software (version 16; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

A total of 205 porcelain laminate veneers fabricated from IPS e.max Press (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Principality of Liechtenstein) were evaluated. Patients ranged in age from 21 to 49 years (mean = 26 years). The follow-up period after veneer placement ranged from less than 6 months to more than 2 years (<6 months, n = 17; 6–12 months, n = 4; 1–1.5 years, n = 4; 1.5–2 years, n = 3; >2 years, n = 1).

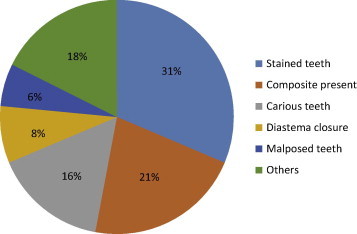

Fig. 1 shows the reasons for the porcelain laminate veneers. Most patients had maxillary restorations (72.4%, n = 21); one patient had a mandibular veneer, and seven patients had veneers in both arches. With regard to the veneer design, three patients had a window design and the rest had an overlapped design. The preparation depth was located in the enamel in 58.6%, dentin in 10.3%, and both enamel and dentin in 31.0% of patients. Finish line placement was equigingival (65.5% of patients), supragingival (24.1%), or both supragingival and equigingival (10.3%).

Figure 1.

Pie diagram of the reasons for porcelain laminate veneers in this study.

The most common impression technique was the one-step double-mix technique; the washout technique was used in three cases. Polyvinyl siloxane impression material was mainly used; polyether impression material was used in two cases (i.e., implant cases). Acrylic resin temporary restorations fabricated in the laboratory were less widely used; composite with or without acid etch and acrylic resin temporary restorations fabricated in the clinic (success CD) were equally used (31%). Moreover, Variolink Veneer (Ivoclar Vivadent) and RelyX veneer cement (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) were used in 65.5% and 34.5% of patients, respectively.

In the clinical examination, bleeding on probing was found in 69% of patients, and 48.3% had plaque on the tooth surface. In addition, 0.5-mm gingival recession was detected in 12 patients (41.4%); the rest showed no sign of gingival recession. One patient had irreversible pulpitis in one tooth after veneer placement; 28 patients had reversible pulpitis, mostly in the veneered teeth.

Marginal pigmentation was observed in 58.6% of patients. It was observed regardless of the veneer design and especially in those with poor oral hygiene and calculus accumulation (Fig. 2). Seventeen patients had excellent marginal adaptation, although seven patients (27.6%) had inappropriate veneer designs, such as a short porcelain margin that did not reach the finish line. Six patients (20.7%) showed a color change after the cementation of their laminate veneers. One reason for the color change was root canal treatment after veneer placement (Fig. 3). No patients had fractured restorations; however, three patients showed incisal wear due to parafunctional habits, such as bruxism and pen biting. Only 10.3% of patients showed debonding (maxillary arch, n = 2; mandibular arch, n = 1); one explanation for this failure was a lack of clinical skills (Fig. 4). Radiographically, the frequency of recurrent caries was low (n = 3).

Figure 2.

Staining on the palatal surfaces of the maxillary teeth associated with high consumption of coffee and tea.

Figure 3.

(a) Slight color changes due to pinpoint pulpal exposure during tooth preparation to receive porcelain laminate veneers on the bilateral maxillary central incisors; the exposed areas were first covered with calcium hydroxide cement and then resin cement. (b) Color change following RCT after the placement of a porcelain laminate veneer on the left maxillary central incisor. (c) Appearance after the glazing layer was removed during finishing and polishing in the maxillary anterior region because the patient complained of pigmentation in these areas.

Figure 4.

(a) Debonding due to inadequate enamel reduction in the mandibular right lateral incisor. (b) Debonding following the cementation of a veneer onto the roughly prepared maxillary right lateral incisor with extensive removal of sound tooth structure, resulting in large exposure of dentin. (c) Recurrent caries (arrow) under a debonded porcelain laminate veneer on the mesial aspect of the maxillary right canine.

Compared to other habits, such as nail and pen biting, bruxism was more associated with sensitivity (83.3%; t-test; P = 0.005). The chi-square test showed that 57.1% of patients with pretreatment sensitivity still had sensitivity after the treatment. Sensitivity was reduced by using composites with acid-etched temporary restorations rather than composites without acid-etched temporary restorations (Table 1). No relationship was noted between coffee, tea, and/or soft drink consumption and color change (Table 2). Marginal pigmentation increased with frequent consumption of these drinks, but the results were not significant.

Table 1.

The values in parentheses represent the number of patients.

| Sensitivity | Recession (%) |

Interim prosthesis (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Composite resin with acid etch | Composite resin without acid etch | Laboratory acrylic resin | Clinical acrylic resin | |

| Sensitive | 50.0 (7) | 50.0 (7) | 14.3 (2) | 35.7 (5) | 7.1 (1) | 42.9 (6) |

| Not sensitive | 33.3 (5) | 66.7 (10) | 46.7 (7) | 26.7 (4) | 6.7 (1) | 20.0 (3) |

Table 2.

The values in parentheses represent the number of patients.

| Status | Smoking (%) |

Coffee consumption (%) |

Tea consumption (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color change | Satisfaction | Color change | Satisfaction | Color change | Satisfaction | |

| Yes | 33.3 (3) | 88.9 (8) | 23.1 (6) | 80.8 (21) | 21.7 (5) | 78.3 (18) |

| No | 66.7 (6) | 11.1 (1) | 76.9 (20) | 19.2 (5) | 78.3 (18) | 21.7 (5) |

Overall, 10 patients (34.48%) showed restoration failure, especially color change (60%). However, 82.8% of patients were satisfied with their restorations.

4. Discussion

In the present study, the success rate of porcelain laminate veneers placed by relatively inexperienced dentists was 65.52%, similar to rates reported by Granell-Ruíz et al. (2013) and Fradeani (1998). This result may be attributed to the improvement of resin cement or the type of veneer material used, and ensures highly retentive restorations with good flexural strength when placed with due consideration for the indications (Giordano and McLaren, 2010). We found that 43.48% of the restorations failed in terms of color change or debonding, although fracture was absent. Similar findings have been reported previously (Calamia, 1989; Chen et al., 2005; Nordbø et al., 1994; Strassler and Nathanson, 1989). The use of IPS e.max Press, in which the core of lithium disilicate crystals with fluorapatite veneering ceramic increases the flexural strength to approximately 450 MPa, may have increased the fracture resistance of the restorations (Giordano and McLaren, 2010). In contrast, many authors (Beier et al., 2012; Christensen and Christensen, 1991; Walls, 1995) reported high fracture rates, which they attributed to parafunctional habits. In the present study, three patients showed incisal wear due to bruxism and one patient showed debonding due to pen biting. Heymann et al. (1991) and Lambrechts et al. (1996) suggested that parafunctional habits can increase microleakage and gap formation, which may impair the retention of porcelain laminate veneers.

Turgut and Bagis (2013) stated that the type and shade of resin cement and the thickness and shade of the ceramic influence the resulting optical color of laminate restorations. This study emphasized a high technical sensitivity of the restorations, wherein a slight contamination or procedural error can spoil the appearance. In this study, the overall incidence of failure was negligible, which may explain why 82.8% of patients were satisfied with their restorations. Good knowledge is required for the restoration procedure to be considered safe to practice by students at different levels. In the current study, color changes were the most common failure type of porcelain laminate veneers. The major cause of these failures was dentist malpractice, such as removal of the glazed layer after finishing and polishing, or failing to clean the pulp chamber from sealers or gutta percha after root canal treatment on previously cemented porcelain laminate veneers.

5. Conclusion

Insufficient clinical skills or operator experience resulted in restoration failure (especially color changes), which was found in one-third of patients. However, 82.8% of patients were satisfied with their restorations.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Mr. Nassr Al-Maflehi.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Beier U.S., Kapferer I., Burtscher D., Dumfahrt H. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers for up to 20 years. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2012;25:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamia J.R., Simonsen R.J. Effect of coupling agents on bond strength of etched porcelain. J. Dent. Res. 1984;63 (abstract 79) [Google Scholar]

- Calamia J.R. Clinical evaluation of etched porcelain veneers. Am. J. Dent. 1989;2:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelnuovo J., Tjan A.H., Phillips K., Nicholls J.I., Kois J.C. Fracture load and mode of failure of ceramic veneers with different preparations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2000;83:171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.H., Shi C.X., Wang M., Zhao S.J., Wang H. Clinical evaluation of 546 tetracycline-stained teeth treated with porcelain laminate veneers. J. Dent. 2005;33:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen G.J., Christensen R.P. Clinical observations of porcelain veneers: a three-year report. J. Esthet. Dent. 1991;3:174–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1991.tb00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen G.J. Thick or thin veneers? J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2008;139:1541–1543. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumfahrt H., Schäffer H. Porcelain laminate veneers. A retrospective evaluation after 1 to 10 years of service: part II—clinical results. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2000;13:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fradeani M. Six-year follow-up with Empress veneers. Int. J. Periodont. Restorat. Dent. 1998;18:216–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M.J. A 15-year review of porcelain veneer failure—a clinician’s observations. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 1998;19:625–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano R., McLaren E.A. Ceramics overview: classification by microstructure and processing methods. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2010;31:682–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R.E., Haywood V.B. In: Esthetics in Dentistry. 2nd ed. Goldstein R.E., editor. vol. 1. BC Decker; Hamilton, Ontario: 1998. p. 14. (Principles, Communications, Treatment Methods). [Google Scholar]

- Granell-Ruíz M., Granell-Ruíz R., Fons-Font A., Román-Rodríguez J.L., Solá-Ruíz M.F. Influence of bruxism on survival of porcelain laminate veneers. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2013 doi: 10.4317/medoral.19097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymann H.O., Sturdevant J.R., Bayne S., Wilder A.D., Sluder T.B., Brunson W.D. Examining tooth flexure effects on cervical restorations: a two-year clinical study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1991;122:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(91)25015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts P., Van Meerbeek B., Perdigão J., Gladys S., Braem M., Vanherle G. Restorative therapy for erosive lesions. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1996;104:229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi B. Porcelain veneers: techniques and precautions. Int. Dent. SA. 2007;9:6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Ziada H.M., Allen P.F. Retrospective study on the performance of porcelain laminate veneers delivered by undergraduate dental students. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2005;13:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M., Takei H.H., Klokkevold P., Carranza F.A. 9th ed. Saunders Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2001. Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology. p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Nordbø H., Rygh-Thoresen N., Henaug T. Clinical performance of porcelain laminate veneers without incisal overlapping: 3-year results. J. Dent. 1994;22:342–345. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(94)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peumans M., Van Meerbeek B., Lambrechts P., Vanherle G. Porcelain veneers: a review of the literature. J. Dent. 2000;28:163–177. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(99)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson T., Heymann H., Swift E. 5th ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2006. Sturdevant’s Art and Science of Operative Dentistry. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Shillingburg H.T., Hobo S., Whitsett L.D., Jacobi R., Brackett S.E. 3rd ed. Quintessence Publishing; Hanover Park, IL: 1997. Fundamentals of Fixed Prosthodontics. p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Strassler H.E., Nathanson D. Clinical evaluation of etched porcelain veneers over a period of 18 to 42 months. J. Esthet. Dent. 1989;1:21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1989.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassler H.E. Minimally invasive porcelain veneer: indications for a conservative esthetic dentistry treatment modality. Gen. Dent. 2007;55:686–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgut S., Bagis B. Effect of resin cement and ceramic thickness on final color of laminate veneers: an in vitro study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2013;109:179–186. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(13)60039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls A.W. The use of adhesively retained all-porcelain veneers during the management of fractured and worn anterior teeth: part 2. Clinical results after 5 years of follow-up. Br. Dent. J. 1995;178:337–340. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]