Abstract

Background: Moving images are often essential in medical education, to learn new procedures and advanced skills, but, in the past, high-quality movie transmission was technically much more challenging than transmitting still pictures because of technological limitations and cost. Materials and Methods: We established a new system, taking advantage of two advanced technologies, the digital video transport system (DVTS) and the research and education network (REN), which enabled satisfactory telemedicine on a routine basis. Results: Between 2003 and 2013, we organized 360 programs connecting 221 hospitals or facilities in 34 countries in Asia and beyond. The two main areas were endoscopy and surgery, with 113 (31%) and 106 (29%) events, respectively. Teleconferences made up 76% of the total events, with the remaining 24% being live demonstrations. Multiple connections were more popular (63%) than one-to-one connections (37%). With continuous technological development, new high-definition H.323 and Vidyo® (Hackensack, NJ) systems were used in 47% and 39% of events in 2011 and 2012, respectively. The evaluation by questionnaires was favorable on image and sound quality as well as programs. Conclusions: Remote medical education with moving images was well accepted in Asia with changing needs and developing technologies.

Key words: : telemedicine, remote education, Internet, research and education network, digital video transport system

Introduction

With the development of the Internet, various trials have been performed to apply this new technology to the field of remote medical education. There are success stories in various fields, including radiology, pathology, and dermatology. Such methods can save time and travel expenses and provide new knowledge to remote audiences in an efficient way.1–3 However, there have been problems with image quality, especially when video contents are included. This is a serious issue in remote education because moving images are often much more helpful as educational materials than still pictures, especially in teaching new skills or demonstrating a procedure.

In such situations, satellite had been the only tool capable of transmitting in satisfactory quality, but the cost was prohibitive for use on a daily basis, and applications were limited to special occasions. Use of the Internet did not provide satisfactory image quality for medical purposes, mainly because research focused on finding the best compression algorithms to preserve the video quality in the limited, narrow bandwidth, making image deterioration inevitable.4,5

The development of the minimally compressed transmission system using the digital video transport system (DVTS) via a research and education network (REN), in 2003, was epoch-making. The quality of the surgical images at the remote site was as clear as in the operating theater.6 In addition, this new system required no costly special videoconferencing system, but worked on a personal computer (PC) with free software. This meant it was rapidly accepted in many regions, especially around Asia.7

The fundamental difference between our project and other remote medical education programs lies in the content. Many programs use slide presentations or discussion with still pictures, and the camera only shows people sitting in front of the monitor, without much movement.8,9 In contrast, our program focuses on medical moving images such as surgery, which require rapid and continuous movement. There is a big technological difference between transmission of still pictures and video. Although it is not problematic to wait a few seconds for a picture transmission, 30 frames per second must be transmitted smoothly, without any pauses, to maintain the image quality for video transmission. This is much more demanding. We believe that practical telemedicine for remote education started with the invention of this new system, particularly for fields where moving images are crucial.

This article summarizes our 10-year experience in remote medical education, mainly in Asia, with the focus on video transmission.

Materials and Methods

We used DVTS as the main tool in our program.6 We downloaded free software from the Web site www.sfc.wide.ad.jp/DVTS/ and installed it on a PC. A digital camera or item of medical equipment was directly connected to the computer through the IEEE1394 interface. To avoid echo and to stabilize the system, we used an audio mixer and analog–digital video converter as a standard configuration.10 After 2011, we were able to use the high-definition (HD) H.323 system from companies such as Polycom (San Jose, CA), Lifesize (Austin, TX), Cisco (San Jose, CA), and Sony (Tokyo, Japan), and we also used the Vidyo® (Hackensack, NJ) system with H.264 compression technology. For multiple connections, we used Quatre (Information Services International-Dentsu, Ltd., Tokyo) for DVTS, a multipoint control unit for H.323, and Vidyo Portal for Vidyo. Participants at all the connected stations could talk to each other. No patient data were transmitted over the network, and patient security was strictly preserved. An REN was essential for DVTS, which required stable bandwidth as big as 30 megabits/s (Mbps).11 However, commercial networks were also used for HD-H.323 and Vidyo when REN was not availablele.

Questionnaires were randomly sent to the audience to evaluate image resolution, image movement, sound quality, and programs. The answers were classified into four levels: very good, good, poor, and very poor.

Results

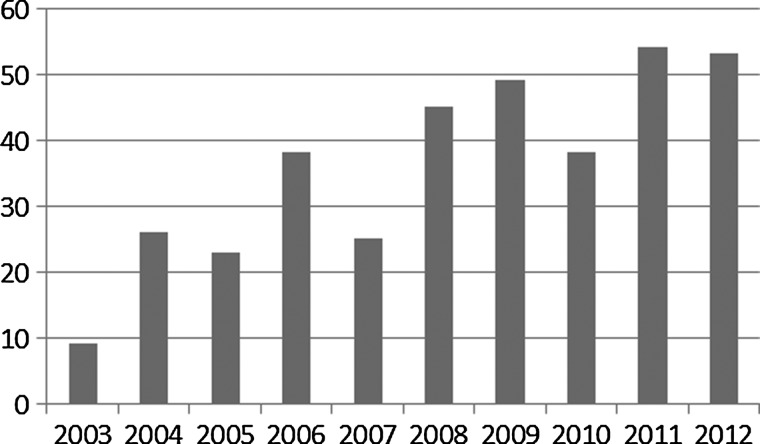

During the 10 years from February 2003 to March 2013, we organized 360 programs from Kyushu University Hospital (Fukuoka, Japan). These were split into 10 groups according to the Japanese fiscal year, with events between April 2003 and March 2004 classified as 2003, from April 2004 to March 2005 as 2004, and so on. The only event before April 2003 was the very first event, which took place in February 2003, which has been included in 2003 for the purposes of analysis. The annual number of events gradually increased, to reach over 50 per year in the most recent 2 years, around once a week (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Total number of programs held in each financial year between 2003 and 2012.

Early programs were largely to Japan and Korea, but the activity expanded rapidly further into Asia and beyond. Table 1 shows the participating countries and regions, in order of the time when they first linked, including the number of events they joined and the number of hospitals or places connected. By March 2013, 34 countries and regions were connected, with 221 sites, and we had made 1,315 connections in total. Japan had the largest number of participating sites and actual connections, 63 and 563, respectively, followed by Korea and China. Other active countries/regions included the United States, Australia, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, India, Singapore, the Philippines, and Malaysia.

Table 1.

Participating Countries and Regions in Order of Connection

| ORDER | COUNTRY/REGION | FIRST CONNECTION (YEAR/MONTH) | NUMBER OF INSTITUTIONS | CONNECTED SITES IN TOTAL | PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL CONNECTIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Japan | 2003/February | 63 | 563 | 42.8 |

| 2 | Korea | 2003/February | 23 | 198 | 15.1 |

| 3 | United States | 2004/January | 12 | 41 | 3.1 |

| 4 | Australia | 2004/July | 13 | 30 | 2.3 |

| 5 | China | 2004/October | 17 | 105 | 8.0 |

| 6 | Taiwan | 2004/December | 9 | 63 | 4.8 |

| 7 | Thailand | 2005/January | 11 | 69 | 5.2 |

| 8 | Singapore | 2005/November | 2 | 37 | 2.8 |

| 9 | Vietnam | 2006/June | 9 | 56 | 4.3 |

| 10 | Indonesia | 2006/July | 2 | 8 | 0.6 |

| 11 | Philippines | 2007/January | 6 | 27 | 2.1 |

| 12 | Malaysia | 2007/January | 6 | 23 | 1.7 |

| 13 | India | 2007/January | 9 | 28 | 2.1 |

| 14 | Germany | 2007/August | 2 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 15 | France | 2007/August | 2 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 16 | Italy | 2007/December | 4 | 4 | 0.3 |

| 17 | Belgium | 2008/May | 1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 18 | New Zealand | 2008/August | 2 | 3 | 0.2 |

| 19 | Czech Republic | 2008/September | 5 | 7 | 0.5 |

| 20 | Spain | 2008/September | 3 | 8 | 0.6 |

| 21 | Egypt | 2009/May | 2 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 22 | Norway | 2009/June | 1 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 23 | Brazil | 2009/June | 3 | 4 | 0.3 |

| 24 | Mexico | 2009/October | 2 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 25 | Lithuania | 2010/June | 1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 26 | Morocco | 2010/June | 1 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 27 | Chile | 2010/November | 1 | 3 | 0.2 |

| 28 | South Africa | 2011/May | 2 | 6 | 0.5 |

| 29 | Fiji | 2011/December | 1 | 4 | 0.3 |

| 30 | United Kingdom | 2012/February | 1 | 2 | 0.2 |

| 31 | Nepal | 2012/March | 2 | 6 | 0.5 |

| 32 | Sri Lanka | 2012/August | 1 | 4 | 0.3 |

| 33 | Turkey | 2012/December | 1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| 34 | Mongolia | 2012/December | 1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Total | 221 | 1,315 | 100.0 |

The United States joined in January 2004, followed by Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, with Germany and France joining in August 2007. In total, 13 countries connected from Europe and Africa. The 12 sites in the Americas contributed to 50 events (4%), and the 18 sites in Europe and Africa contributed to 40 (3%). We held only 47 programs (13%) within Japan alone. The remaining 87% all included international connections. The official language for international programs was English, whereas Japanese was used in domestic sessions in Japan.

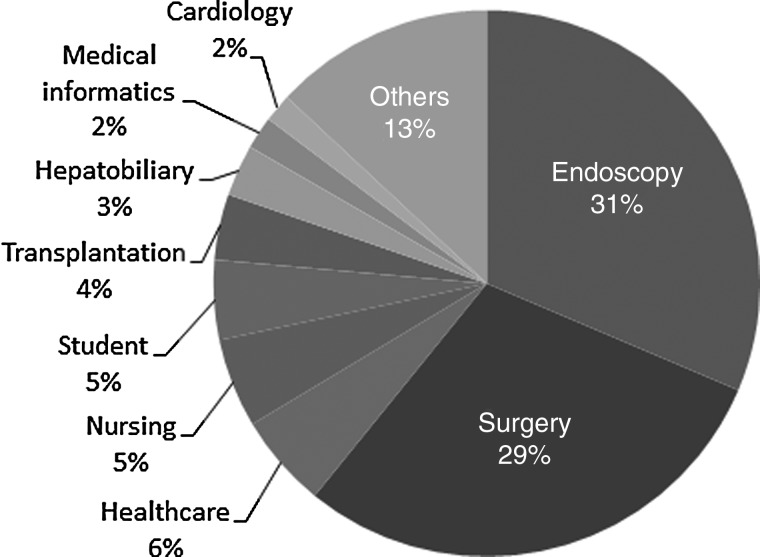

The programs of the 360 events were analyzed according to the content (Fig. 2). Endoscopy and surgery were by far the most popular fields, followed by healthcare and nursing, with the remaining 29% divided among various subjects.

Fig. 2.

Areas of content of the 360 programs.

The programs were divided into two groups: teleconferences and live demonstrations. Teleconferences are used for presentations with slides and recorded videos, whereas live demonstrations show medical procedures in clinical settings, with patients. Teleconferences accounted for 76% (272/360) of the programs, and 24% were live demonstrations. When the total was subdivided according to the program content, live demonstrations made up 39% (41/106) of surgical programs and 25% (28/113) of endoscopy programs.

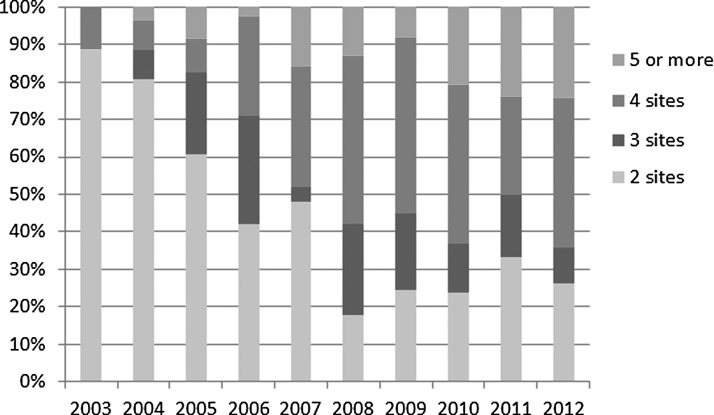

One-to-one connections between two sites were made in 132 events (37%), and the rest (63%) included three or more stations. Four-site connections were the second most common, with 117 programs (33%), and the largest number of simultaneous connection sites was 14 with DVTS and H323 and 16 with Vidyo. The changes in connection numbers are shown in Figure 3, which highlights the rapidly increasing demand for multiple connections. The percentage of four-site connection was higher than one-to-one connection in all of the most recent 5 years, except 2011.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of multiple connections in each year.

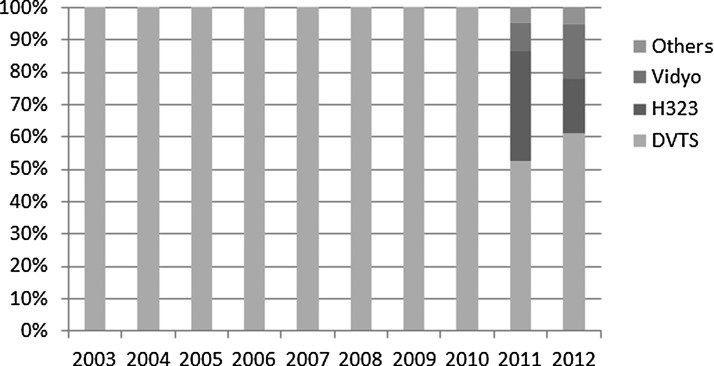

As shown in Figure 4, DVTS was used in 87% (317/360) of programs across the 10 years, but other systems became popular and were used in 47% of programs in 2011 and 39% in 2012. HD-H.323 accounted for 34% and 17% of events in 2011 and 2012, respectively, and Vidyo accounted for 8% and 17%, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Systems used for programs in each year.

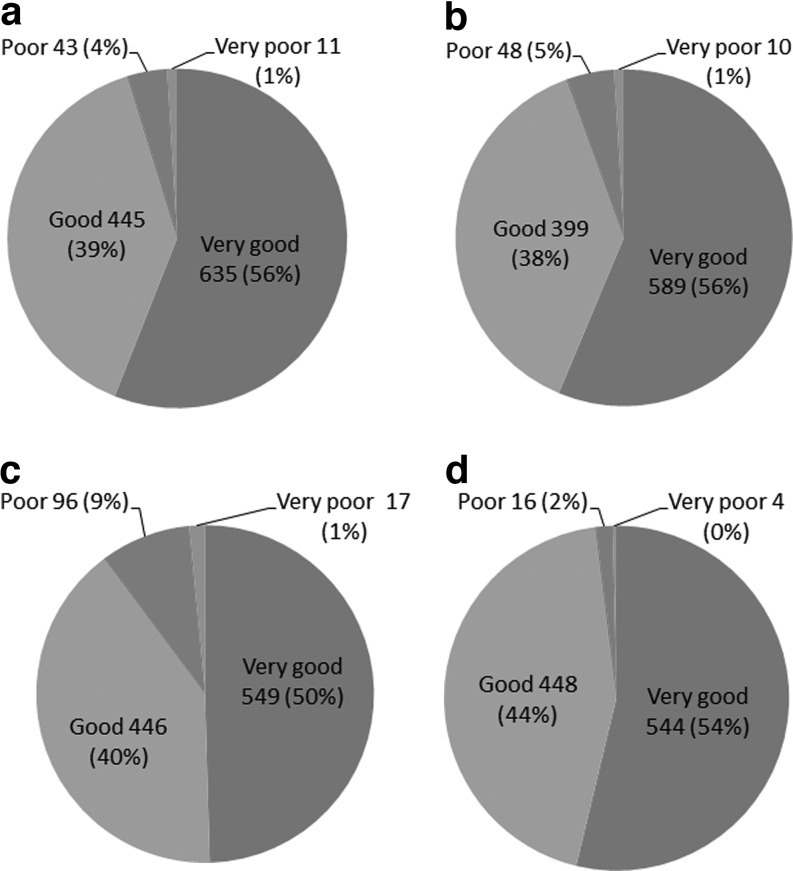

The answers for the questionnaires were collected from 1,134, 1,046, 1,108, and 1,012 participants for image resolution, image movement, sound quality, and programs, respectively. The results are shown in Figure 5. For all the categories, participants were favorably impressed with both systems and programs, with more than 90% commenting that they were “very good” or “good.”

Fig. 5.

Evaluation by questionnaire of (a) image resolution, (b) image movement, (c) sound quality, and (d) program.

Discussion

Our teleconference system, first developed in 2003, has been proved to be well accepted by the medical community. This novel system transmitted moving images at a satisfactory level of quality to meet the needs of doctors, at a much lower cost than more conventional systems. Endoscopy and surgery were the most common programs that require moving images for transmission not only of new knowledge but also of advanced procedures and skills. The rapid expansion and acceptance of this project in many Asian countries and beyond showed that there was a need for high-quality remote medical education around the globe, including for specialists, young doctors, and other medical staff such as nurses, researchers, and students. Multiple connections became popular because the technology became less challenging, and participants enjoyed discussions with many sites.

For this success, an REN was essential and played a key role throughout the 10 years. Until recently, DVTS was the only tool accepted in our community, in terms of both image quality and cost, which required a huge network, as big as 30 Mbps, which could be kept stable throughout the program to maintain the image in high resolution and smooth motion. The REN was first introduced in the United States as “computer networking for scientists” in 1986 and is now established in many countries and regions both domestically and internationally.12 Many such networks are government-funded or run by nonprofit organizations, and higher education establishments as well as research centers are well connected.11 These institutions can use this high-speed Internet anytime, without additional cost for individuals. In Japan, for example, the Science Information Network (SINET) is funded by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and around 700 centers are connected. Internet2 is the REN in the United States that connects around 250 leading universities. There are international RENs that connect these domestic RENs, such as the Asia-Pacific Advanced Network (APAN) in Asia-Pacific, GEANT2 in Europe, and RedClara in Latin America.13

However, the situation has changed over recent years, for example, with the emergence of HD-quality medical images. When the project started, standard definition was the best quality, and DVTS fitted it well. However, when HD quality became available, some doctors became unhappy with the conventional quality of images. In addition, those who were not connected to an REN also wanted to join the project, using commercial networks. Although RENs now connect so many institutions worldwide and provide a much better network than commercial networks, there are still many hospitals that are not connected to the REN. Thanks to continuous technological development and network refinement, the programs have been able to meet these two demands recently, at least in part. We have chosen two other newly developed systems, HD-H.323 and Vidyo, as our standard systems, as they meet three conditions: (1) they have global availability and support, (2) they offer high quality of video images, and (3) the cost is reasonable. Each system, however, has its pros and cons.14

International telemedicine should be more beneficial and effective than domestic, because of the educational impact, but there are issues that arise in leading and organizing international teleconferences and live demonstrations. First, we need to select the most suitable system to deliver the programs, taking into account the technological situation in all the participating hospitals. If all the participants have an HD-H.323 videoconferencing system, not standard definition-H.323, in their own hospitals, H.323 may be the easiest. But, the participants were rarely so well equipped, especially in Asia, with many developing countries. In addition, even if the technology was available, the compatibility between company brands and the quality of the multipoint control unit for multiple connections often bothered us. Vidyo is now a very convenient tool because the client only needs a PC and Webcam, without the need for a global Internet protocol address, but it is more difficult when we need to transmit high-quality videos from every site because additional expensive equipment is necessary in each location. DVTS is therefore still actively used, as it offers the benefits of low cost and ability to transmit high-quality movies between multiple stations. Although it is only standard definition, the quality of DVTS is probably comparable with that of HD-H.323 and Vidyo, which use compression of HD images.15 More detailed evaluation of these systems is necessary.

The last 10 years have seen the start of practical telemedicine used on a routine basis and of DVTS and the REN in a technological sense. What can we expect in the next 10 years? We expect mobile devices to be used much more often in remote medical education. More and more people will be able to join programs using handy equipment in ubiquitous conditions. The last 10 years have also seen us struggling with technology. With immature networks and primitive conditions in many hospitals, we experienced various difficulties in establishing a satisfactory system at each hospital and learned plenty about troubleshooting Internet and audiovisual problems. Over the next 10 years, we hope to encounter fewer technical problems, thanks to better equipment and increased Internet capacity, so that we will be able to focus more on the programs, to make them even more attractive and educational. We also hope that more and more medical staff will understand the benefits of continuous remote medical education and organize an increasing variety of programs expanding into as yet unexplored fields. In conclusion, our most important lesson from the last 10 years has been that, regardless of changes in needs and demands, cooperation between medical and engineering staff will remain vitally important for the success of telemedicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the cooperation and expertise of the entire medical and engineering staff in supporting program organization and network preparations at all the hospitals and institutions involved. We are particularly grateful to the APAN-NOC and TEIN-NOC teams for intensive network preparations. This project was funded in part by Grant-in-Aid number 23256005 for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Saliba V, Legido-Quigley H, Hallik R, Aaviksoo A, Car J, McKee M. Telemedicine across borders: A systematic review of factors that hinder or support implementation. Int J Med Informa 2012;81:793–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstein RS, Graham AR, Lian F, Braunhut BL, Barker GR, Krupinski EA, Bhattacharyya AK. Reconciliation of diverse telepathology system designs. Historic issues and implications for emerging markets and new applications. APMIS 2012;120:256–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wootton R, Bahaadinbeigy K, Hailey D. Estimating travel reduction associated with the use of telemedicine by patients and healthcare professionals: Proposal for quantitative synthesis in a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabenstein T, Maiss J, Naegele-Jackson S, Liebl K, Hengstenberg T, Radespiel-Troger M, Holleczek P, Hahn EG, Sackmann M. Tele-endoscopy: Influence of data compression, bandwidth and simulated impairments on the usability of real-time digital video endoscopy transmissions for medical diagnoses. Endoscopy 2002;34:703–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rafiq A, Moore JA, Zhao X, Doarn CR, Merrell RC. Digital video capture and synchronous consultation in open surgery. Ann Surg 2004;239:567–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimizu S, Nakashima N, Okamura K, Hahm JS, Kim YW, Moon BI, Han HS, Tanaka M. International transmission of uncompressed endoscopic surgery images via super-fast broadband Internet connections. Surg Endosc 2006;20:167–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu S, Nakashima N, Okamura K, Tanaka M. One hundred case studies of Asia-Pacific telemedicine using a digital video transport system over a research and education network. Telemed J E Health 2009;15:112–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mars M. Building the capacity to build capacity in e-health in sub-Saharan Africa: The KwaZulu-Natal experience. Telemed J E Health 2012;18:32–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AC, White MM, McBride CA, Kimble RM, Armfield NR, Ware RS, Coulthard MG. Multi-site videoconference tutorials for medical students in Australia. ANZ J Surg 2012;82:714–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimizu S, Okamura K, Nakashima N, Kitamura Y, Torata N, Tanaka M. Telemedicine with digital video transport system over a worldwide academic network. In: Martinez L, Gomez C, eds. Telemedicine in the 21st century. New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2008:143–164 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu S, Han HS, Okamura K, Nakashima N, Kitamura Y, Tanaka M. Technologic developments in telemedicine: State-of-the-art academic interactions. Surgery 2010;147:597–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jennings DM, Landweber LH, Fuchs IH, Farber DJ, Adrion WR. Computer networking for scientists. Science 1986;231:943–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimizu S, Okamura K, Nakashima N, Kitamura Y, Torata N, Yamashita T, Yamanokuchi T, Kuwahara S, Tanaka M. High-quality telemedicine using digital video transport system over global research and education network. In: Graschew G, Roelofs TA, eds. Advances in telemedicine: Technologies, enabling factors and scenarios. Rijeka: Intech, 2011:87–110 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao MD, Shimizu S, Antoku Y, Torata N, Kudo K, Okamura K, Nakashima N, Tanaka M. Emerging technologies for telemedicine. Korean J Radiol 2012;13(Suppl 1):S21–S30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu WL, Zhang K, Locatis C, Ackerman M. Internet-based videoconferencing coder/decoders and tools for telemedicine. Telemed J E Health 2011;17:358–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]