Abstract

Background

The burden of coronary heart disease (CHD) worldwide is one of great concern to patients and healthcare agencies alike. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation aims to restore patients with heart disease to health.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (exercise training alone or in combination with psychosocial or educational interventions) on mortality, morbidity and health-related quality of life of patients with CHD.

Search methods

RCTs have been identified by searching CENTRAL, HTA, and DARE (using The Cochrane Library Issue 4, 2009), as well as MEDLINE (1950 to December 2009), EMBASE (1980 to December 2009), CINAHL (1982 to December 2009), and Science Citation Index Expanded (1900 to December 2009).

Selection criteria

Men and women of all ages who have had myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), or who have angina pectoris or coronary artery disease defined by angiography.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were selected and data extracted independently by two reviewers. Authors were contacted where possible to obtain missing information.

Main results

This systematic review has allowed analysis of 47 studies randomising 10,794 patients to exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation or usual care. In medium to longer term (i.e. 12 or more months follow-up) exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation reduced overall and cardiovascular mortality [RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.75, 0.99) and 0.74 (95% CI 0.63, 0.87), respectively], and hospital admissions [RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.51, 0.93)] in the shorter term (< 12 months follow-up) with no evidence of heterogeneity of effect across trials. Cardiac rehabilitation did not reduce the risk of total MI, CABG or PTCA. Given both the heterogeneity in outcome measures and methods of reporting findings, a meta-analysis was not undertaken for health-related quality of life. In seven out of 10 trials reporting health-related quality of life using validated measures was there evidence of a significantly higher level of quality of life with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation than usual care.

Authors’ conclusions

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is effective in reducing total and cardiovascular mortality (in medium to longer term studies) and hospital admissions (in shorter term studies) but not total MI or revascularisation (CABG or PTCA). Despite inclusion of more recent trials, the population studied in this review is still predominantly male, middle aged and low risk. Therefore, well-designed, and adequately reported RCTs in groups of CHD patients more representative of usual clinical practice are still needed. These trials should include validated health-related quality of life outcome measures, need to explicitly report clinical events including hospital admission, and assess costs and cost-effectiveness.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): *Exercise Therapy, Coronary Disease [mortality; *rehabilitation], Health Status, Myocardial Infarction [mortality; rehabilitation], Myocardial Revascularization [statistics & numerical data], Outcome Assessment (Health Care), Quality of Life, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

MeSH check words: Female, Humans, Male

BACKGROUND

Description of the condition

Cardiovascular disease accounts for one-third of deaths globally, with 7.22 million deaths from coronary heart disease (CHD) in 2002 (WHO 2004). In Europe, CHD is the most common cause of death and in the UK it accounts for one in five deaths in men and one in six deaths in women (British Heart Foundation 2005; Peterssen 2005). Although the mortality rate from CHD has been falling in the UK, principally due to a reduction in risk factors, particularly smoking, it has fallen less than in many other developed countries (Peterssen 2005). Treatments to individuals, including secondary prevention, explain about 42% of the decline in CHD mortality in the 1980s and 1990s (Unal 2000).

Description of the intervention

Cardiac rehabilitation has been defined as the “coordinated sum of interventions required to ensure the best physical, psychological and social conditions so that patients with chronic or post-acute cardiovascular disease may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume optimal functioning in society and, through improved health behaviours, slow or reverse progression of disease” (Fletcher 2001). It is a complex intervention that may involve a variety of therapies, including exercise, risk factor education, behaviour change, psychological support, and strategies that are aimed at targeting traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Cardiac rehabilitation is an essential part of contemporary heart disease care and is considered a priority in countries with a high prevalence of CHD. International clinical guidelines consistently identify exercise therapy as a central element of cardiac rehabilitation (Balady 2007; Graham 2007; NICE 2007) i.e. ‘exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation’.

Despite the recommendations for exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation as an integral component of comprehensive cardiac care of patients with CHD (particularly those following myocardial infarction, revascularization or with angina pectoris) and heart failure, most patients do not receive it (Bethall 2008). Service provision, though predominantly hospital based, varies markedly, and referral, enrolment and completion are suboptimal, especially among women and older people (Beswick 2004). Costs of cardiac rehabilitation services vary by format of delivery. The UK survey suggests that costs can range of £50 to £712 per patient treated depending on the level of staffing, the equipment used and the intensity of the programme (Evans 2002).

Previous meta-analyses of the effects of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for CHD patients reported a statistically significant reduction in total and cardiac mortality, ranging from 20% to 32%, in patients receiving exercise therapy compared with usual medical care (Clark 2005; Jolliffe 2001; Oldridge 1988; O’Connor 1989). However, the evidence for psychological interventions is less convincing. A Cochrane review showed no evidence of an effect on total mortality, cardiac mortality, or revascularisation although there was a significant reduction in the number of non-fatal infarctions in the psychological intervention group (OR 0.78 [95% CI 0.67 to 0.90]) compared to usual care (Rees 2004). A Cochrane review of the effect of educational interventions for CHD is currently being undertaken (Brown 2010).

How the intervention might work

Exercise training has been shown to have direct benefits on the heart and coronary vasculature, including myocardial oxygen demand, endothelial function, autonomic tone, coagulation and clotting factors, inflammatory markers, and the development of coronary collateral vessels (Clausen 1976; Hambrecht 2000). However, findings of the original Cochrane review of exercisebased cardiac rehabilitation for CHD supported the hypothesis that reductions in mortality may also be mediated via the indirect effects of exercise through improvements in the risk factors for atherosclerotic disease (i.e. lipids, smoking and blood pressure) (Taylor 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Our original Cochrane review published in 2001 identified a total of 35 RCTs in some 8,440 patients (Jolliffe 2001). This review reported a reduction in total mortality (random effects model, odds ratio: 0.73, 95% confidence interval: 0.54 to 0.98) with exercise intervention compared to usual care. Improvements with exercise were also seen in cardiac death, non-fatal MI, lipid profile and blood pressure. However, the authors identified a number a limitations in the evidence base:

Trials enrolled almost exclusively low-risk, middle-aged men after myocardial infarction. The exclusion or under representation of women, elderly people, and other cardiac groups (post revascularization and angina pectoris) not only limits the applicability of the evidence to contemporary cardiovascular practice but also fails to consider those who may benefit most from rehabilitation.

The widespread introduction of a variety of drug therapies as part of the routine management of CHD the cardiac patient that were not available at the time of the earliest trials may offset the magnitude of benefit associated with exercise-based rehabilitation.

It was unclear whether comprehensive (exercise plus psychosocial and/or educational interventions) cardiac rehabilitation offers incremental outcome benefits compared to exercise only interventions.

There was a lack of robust evidence for the impact on patient health-related quality of life, costs and cost-effectiveness.

Additionally, recent meta-analyses of the effects of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with CHD have indicated an increase in the number of RCTs since the publication of the original Cochrane review (Clark 2005).

The aim of this study is to update the original Cochrane systematic review of the effects of exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with CHD.

Changes in this update review

In addition to updating the searches, this update review has: (1) formally explored the variation in exercise intervention effects using meta-regression and stratified meta-analysis and (2) not updated exercise capacity and cardiac risk outcomes (i.e. serum lipids, blood pressure, and smoking behaviour).

OBJECTIVES

To assess the effectiveness of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (exercise training alone or in combination with psychosocial or educational interventions) compared with usual care on mortality, morbidity and health-related quality of life in patients with CHD.

To explore the potential study level predictors of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with CHD.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation versus usual care with a follow-up period of at least six months have been sought.

Types of participants

Men and women of all ages, in both hospital-based and community-based settings, who have had a myocardial infarction (MI), or who had undergone revascularisation (coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or coronary artery stent), or who have angina pectoris or coronary artery disease defined by angiography have been included.

Studies of participants following heart valve surgery, with heart failure, with heart transplants or implanted with either cardiac-resynchronisation therapy (CRT) or implantable defibrillators (ICD) have been excluded. Studies of participants who completed a cardiac rehabilitation programme prior to randomisation have also been excluded.

Types of interventions

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is defined as a supervised or unsupervised inpatient, outpatient, or community- or home-based intervention including some form of exercise training that is applied to a cardiac patient population. The intervention could be exercise training alone or exercise training in addition to psychosocial and/or educational interventions (i.e. “comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation”).

Usual care could include standard medical care, such as drug therapy, but did not receive any form of structured exercise training or advice.

Types of outcome measures

All clinical events or other outcome measures reported post-randomisation were included in this review. No maximum limit was imposed on the length of follow-up.

Primary outcomes

- Total mortality

-

○Cardiovascular mortality

-

○Non-cardiovascular mortality

-

○

- Total MI

-

○Fatal MI

-

○Non-fatal MI

-

○

- Total revascularizations

-

○CABG

-

○PTCA

-

○Restenting

-

○

- Total hospitalisations

-

○Cardiovascular hospitalisations

-

○Other hospitalisations

-

○

Secondary outcomes

Health-related quality of life assessed using validated instruments (e.g. SF-36, EQ5D)

Costs and cost-effectiveness

Search methods for identification of studies

As this review forms part of a broader review strategy, that includes updates of two other Cochrane systematic reviews addressing cardiac rehabilitation (Davies 2010a; Rees 2004) and two new Cochrane reviews - interventions for enhancing uptake and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation (Davies 2010b) and home versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation (Taylor 2010), a generic broad search was initially undertaken. This generic search was then further updated for the purposes of this specific review.

Electronic searches

Randomized controlled trials have been identified from the previously published Cochrane review. This list of studies has been updated by the authors searching the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library Issue 4, 2009, MEDLINE (November 2000 to December 2009), EM-BASE (November 2000 to December 2009), CINAHL (November 2000 to December 2009), and Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-Expanded, 1900 to December 2009). Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) databases have been searched via The Cochrane Library Issue 4, 2009. The generic (cross review) search was undertaken from 2001 (the search end date of the previous Cochrane review of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (Jolliffe 2001)) to January 2008 with a further update search up to December 2009 for this specific review.

Search strategies were designed with reference to those of the previous systematic review (Jolliffe 2001). MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL were searched using a strategy combining selected MeSH terms and free text terms relating to exercise-based rehabilitation and coronary heart disease with RCT filters. The MED-LINE search strategy was translated into the other databases using the appropriate controlled vocabulary as applicable. Due to time and resource constraints, three databases (AMED, BIDS and SPORTSDISCUSS) included the previous review (Jolliffe 2001) were not searched in this case.

Searches have been limited to randomised controlled trials and a filter applied to limit by humans. Consideration was given to variations in terms used and spellings of terms in different countries so that studies were not missed by the search strategy because of such variations.

See Appendix 1 for a list of the search strategies used.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of retrieved articles and systematic reviews and meta-analyses published since the original Cochrane review were checked for any studies not identified by the electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The titles and abstracts of citations identified by the electronic searches prior to 2008 were examined for possible inclusion by two reviewers (RST & Philippa Davies) working independently. The titles and abstracts of citations identified by the electronic searches from 2008 onwards were examined for possible inclusion independently by two reviewers (BSH & LF). Full publications of potentially relevant studies were retrieved (and translated into English where required) and two reviewers (BSH & JMHC) then independently determined study eligibility using a standardized inclusion form. Any disagreements about study eligibility were resolved by discussion and, if necessary, a third reviewer (RST) was asked to arbitrate.

Data extraction and management

Data from included studies were extracted by one reviewer (BSH or JMHC) using standardised data extraction forms and checked by a second reviewer (JMHC or BSH). If data were presented numerically (in tables or text) and graphically (in figures), the numeric data were used because of possible measurement error when estimating from graphs. A second reviewer confirmed all numeric calculations and extractions from graphs or figures. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data on patient characteristics (e.g. age, sex, CHD diagnosis) and details of the intervention (including mode of exercise, duration, frequency and intensity), nature of usual care and length of followup were also extracted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers (BSH, JMHC) independently assessed the risk of bias in included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s recommended tool, which is a domain-based critical evaluation of the following domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; and selective outcome reporting (Higgins 2011). Assessments of risk of bias are provided in the Risk of bias table for each study.

Dealing with missing data

If there were multiple reports of the same study, the duplicate publications were scanned for additional data. Outcome results have been extracted at all follow-up points post-randomisation. Study authors were contacted where necessary to provide additional information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

If there was significant statistical heterogeneity (P-value <0.10) associated with an effect estimate, a random effects model was applied. This model provides a more conservative statistical comparison of the difference between intervention and control because a confidence interval around the effect estimate is wider than a confidence interval around a fixed effect estimate. If a statistically significant difference was still present using the random effects model, the fixed effect pooled estimate and 95% CI have been reported because of the tendency of smaller trials, which are more susceptible to publication bias, to be over weighted with a random effects analysis (Heran 2008a; Heran 2008b).

Assessment of reporting biases

No language restrictions have been applied.

Data synthesis

Data have been processed in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Data synthesis and analyses have been done using Review Manager 5.0 software and STATA version 10 (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas).

Dichotomous outcomes for each comparison have been expressed as relative risks with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Continuous outcome have been expressed as the mean (±SD) change from baseline to follow-up. Otherwise, continuous outcomes have been pooled as weighted mean difference (WMD). If there was a statistically significant absolute risk difference, the associated number needed to treat/harm was calculated.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where possible, stratified meta-analysis (according to time of follow-up, 6 to12 months versus > 12 months) and meta-regression have been undertaken to explore heterogeneity and examine potential treatment effect modifiers. We tested five a priori hypotheses that there may be differences in the effect of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation on total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, total MI, and revascularisation (CABG and PTCA) across particular subgroups: (1) CHD case mix (myocardial infarction-only trials versus other trials); (2) type of cardiac rehabilitation (exercise-only cardiac rehabilitation versus comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation); (3) ‘dose’ of exercise intervention [dose = duration in weeks x number of sessions x number of sessions per week] (dose ≥ 1000 units versus dose < 1000 units); (4) follow-up period (≤ 12 months versus > 12 months); and (5) year of publication (before 1995 versus 1995 or later).

Year of Publication

We included year of publication as a study level factor (pre versus post-1995) in order to assess the potential effect of a change in the standard of usual care over time, that is to reflect when pharmacologic agents became established therapies for CHD.

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity amongst included studies was explored qualitatively (by comparing the characteristics of included studies) and quantitatively (using the chi-squared test of heterogeneity and I2 statistic). Where appropriate, data from each study have been pooled using a fixed effect model, except where substantial heterogeneity exists. We planned to pool the results for health-related quality of life using a standardised mean difference (SMD) but this was not possible due to the heterogeneity in outcome measures and methods of reporting findings.

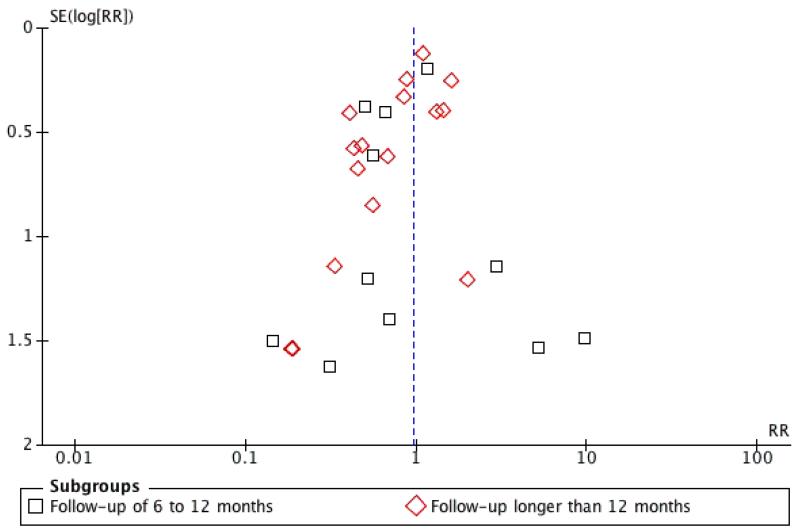

The funnel plot and the Egger test have been used to examine small study bias (Egger 1997).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Results of the search

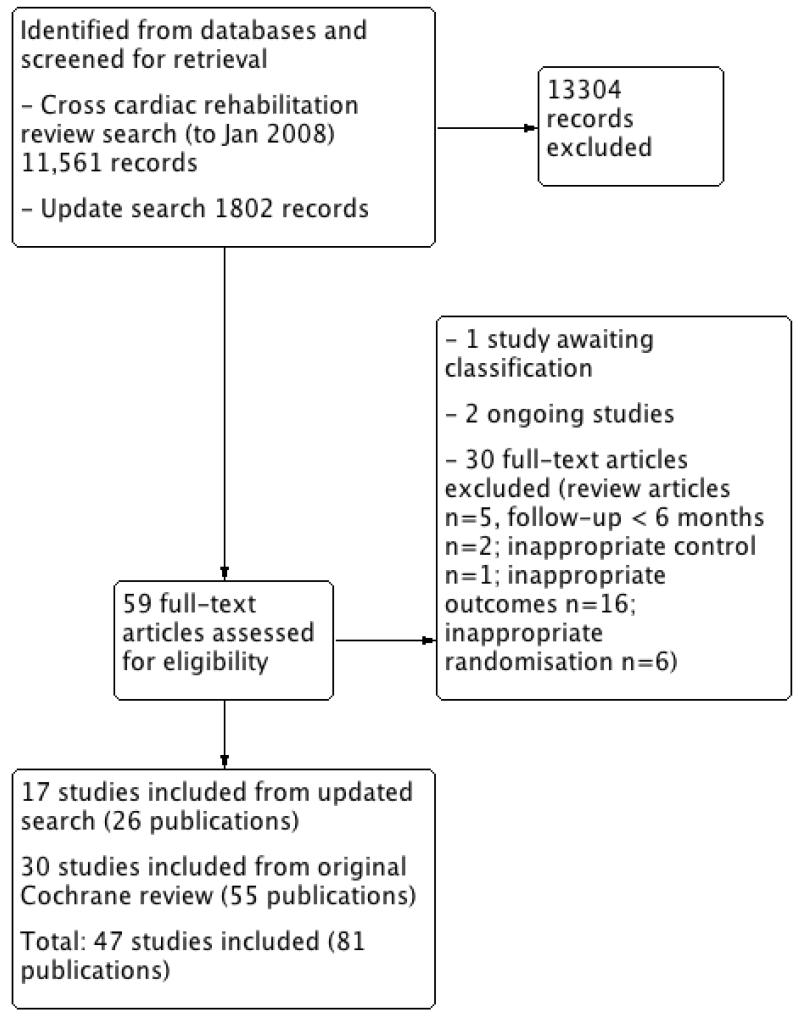

Our update cross-cardiac rehabilitation review electronic searches (to January 2008) yielded a total 11,561 titles plus 1802 titles from the update search (to December 2009). After reviewing the titles and abstracts, we retrieved 59 full-text articles for possible inclusion. A total of 30 papers were excluded: two had followup less than six months, 16 reported no useful outcomes, six had inappropriate randomisation, one had an inappropriate control, and five were review articles. In addition, one study was awaiting classification and two were ongoing studies. Seventeen studies (26 publications) met the inclusion criteria and had extractable data to assess the effects of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care on mortality and morbidity in patients with CHD (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The original Cochrane review published in 2001 (Jolliffe 2001) included a total of 35 studies, of which five studies were judged not to meet the revised inclusion criteria of this review update (see Excluded studies).

In addition to the 30 trials (55 publications) from the original Cochrane review that met the inclusion criteria of this update review (Andersen 1981; Bell 1998; Bengtsson 1983; Bertie 1992; Bethell 1990; Carlsson 1998; Carson 1982; DeBusk 1994; Engblom 1996; Erdman 1986; Fletcher 1994; Fridlund 1991; Haskell 1994; Heller 1993; Holmbäck 1994; Kallio 1979; Leizorovicz 1991; Lewin 1992; Miller 1984; Oldridge 1991; Ornish 1990; Schuler 1992; Shaw 1981; Sivarajan 1982; Specchia 1996; Stern 1983; Vecchio 1981; Vermeulen 1983; WHO 1983; Wilhelmsen 1975), an additional 17 studies (26 publications) have been identified by the updated search and have met the revised inclusion criteria (Belardinelli 2001; Bäck 2008; Dugmore 1999; Giallauria 2008; Hofman-Bang 1999; Kovoor 2006; La Rovere 2002; Manchanda 2000; Marchionni 2003; Seki 2003; Seki 2008; Ståhle 1999; Toobert 2000; VHSG 2003; Yu 2003; Yu 2004; Zwisler 2008). Thus, a total of 47 studies reporting data for a total of 10,794 patients have been included in this review update. Details of the studies included in the review are listed in the Characteristics of included studies table. The study selection process is summarised in the PRISMA flow diagram shown in Figure 1.

Although all exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation, 17 studies were judged to be exercise-only intervention trials and 29 were judged to be comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (exercise plus psychosocial and/or educational interventions); one trial randomly assigned patients to both exercise-only cardiac rehabilitation and comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (Sivarajan 1982). The majority of studies were (32 studies, 68%) undertaken in Europe, either as single or multicenter studies. Trial sample sizes varied widely from 28 to 2304, with a median intervention duration of three (range 0.25 to 30) months and a follow-up of 24 (range six to 120) months. Patients with myocardial infarction alone were recruited in 30 trials (64%); the remaining trials recruited either exclusively postrevascularisation patients (i.e., CABG and PTCA) or both groups of patients. The ages of patients in the trials ranged from 46 to 84 years. Although over half of the trials (28 studies, 60%) included women, on average women accounted for only 20% of the patients recruited.

Characteristics of included interventions

Twenty nine studies compared comprehensive programmes (that is, exercise plus education or psychological management, or both), while 17 reported on an exercise only intervention. In addition, one study randomised patients to a comprehensive programme, exercise only intervention or usual care (Sivarajan 1982).

The exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programmes differed considerably in duration (range 1-12 months), frequency (1-7 sessions/week), and session length (20-90 minutes/session). Most programmes involved the prescription of individually tailored exercise programmes, which makes it difficult to precisely quantify the amount of exercise undertaken. Most home based programmes included a short initial period of centre based intervention. Centre based programmes typically involved supervised exercise involving cycles, treadmills or weight training, while nearly all home based programmes were based on walking.

Both intervention and control patients received usual care including medication, education and advice about diet and exercise, but control patients received no formal exercise training.

Excluded studies

Five studies that had been included in the original review failed to meet the revised inclusion criteria of this review update. Of these, four studies did not report outcomes relevant to this review (Ballantyne 1982; Carlsson 1997; Krachler 1997; Wosornu 1996) and one study was not randomised (Kentala 1972). For the updated search, 24 studies (25 publications) were excluded for reasons listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, with the most common reason being a failure to report any of the pre-specified outcomes of this review update.

Risk of bias in included studies

Limited reporting of the methodology and outcome data in the published papers of the included trials precluded us, in most cases, from adequately performing a critical evaluation of the following domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. Nevertheless, we attempted to assess the risk of bias for each of the 47 included studies given the available information in the published trial reports.

Allocation

Nearly all the trial publications simply reported that the trial was “randomised” but did not provide any details. A total of 8/47 (17%) studies (Andersen 1981; Bell 1998; Bethell 1990;Erdman 1986; Haskell 1994; Holmbäck 1994; Wilhelmsen 1975;Zwisler 2008) reported details of appropriate generation of the random sequence and 7/47 (15%) studies (Bell 1998; Haskell 1994; Holmbäck 1994; Kovoor 2006; Schuler 1992; VHSG 2003;Zwisler 2008) reported appropriate concealment of allocation.

Blinding

For exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation trials, it is not possible to blind patients and clinicians to the intervention. For the large majority of studies, insufficient information was provided to evaluate the blinding of assessors; only 4 of 47 (9%) studies (Fletcher 1994; Ornish 1990; Wilhelmsen 1975; Zwisler 2008) reported that outcome assessors were blind to group allocation.

Incomplete outcome data

Losses to follow-up and drop out were relatively high, ranging from 21% to 48% in 12 trials. Follow-up of 80% or more was achieved in 33/47 (70%) studies (Andersen 1981; Belardinelli 2001; Bell 1998; Bethell 1990; Bäck 2008; Carlsson 1998; Dugmore 1999;Engblom 1996; Giallauria 2008; Haskell 1994; Heller 1993;Holmbäck 1994; Kallio 1979; Kovoor 2006; La Rovere 2002;Leizorovicz 1991; Lewin 1992; Manchanda 2000; Marchionni 2003; Miller 1984; Oldridge 1991; Schuler 1992; Seki 2003;Shaw 1981; Specchia 1996; Stern 1983; Ståhle 1999; Toobert 2000; Vermeulen 1983; VHSG 2003; Wilhelmsen 1975; Yu 2003;Zwisler 2008). Furthermore, reasons for loss to follow and dropout were often not reported. Two trials (Seki 2008; WHO 1983) did not report information on losses to follow-up. Several trials have excluded significant numbers of patients post-randomisation, and thus in an intention to treat analysis, these then have been regarded as dropouts.

Selective reporting

A number of the included studies were not designed to assess treatment group differences in morbidity and mortality (as these were not the primary outcomes of these trials) and, therefore, may not have fully reported all clinical events that occurred during the follow-up period. All studies collecting validated health-related quality of life outcomes fully reported these outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

Publication bias

In order to test for the possibility of publication bias, the funnel plots were created for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, recurrent MI, and revascularisation (CABG and PTCA). There was no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry or significant Egger tests for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and revascularisation (CABG and PTCA). However, the funnel plot of recurrent MI suggests asymmetry and the Egger test was statistically significant (P = 0.019), which appears to be due to an absence of negative-result trials of small to medium size (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Funnel plot of exercise-based rehabilitation versus usual care for fatal and/or nonfatal MI.

Effects of interventions

Clinical Events

Mortality

Thirty (N = 8971) of the included studies reported total mortality (Analysis 1.1); two trials reported both follow-up to 12 months and longer than 12 months (Wilhelmsen 1975; WHO 1983). In studies reporting follow-up longer than 12 months, compared with control, total mortality was reduced with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (RR 0.87 [95% CI 0.75, 0.99]). There was no significant difference in total mortality up to 12 months follow-up.

Nineteen (N = 6583) of included studies reported cardiovascular mortality (Analysis 1.2); one trial reported both follow-up to 12 months and longer than 12 months (WHO 1983). In studies reporting follow-up longer than 12 months, compared to control, cardiovascular mortality was reduced with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (RR 0.74 [95% CI 0.63, 0.87]). There was no significant difference in cardiovascular mortality up to 12 months follow-up.

There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity across trials for either total or cardiovascular mortality.

Morbidity

Twenty-five (N = 7294), 22 (N = 4392), and 11 (N = 2241) of the included studies reported total MI, CABG or PTCA, respectively (Analysis 1.3; Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5); follow-up to 12 months and longer than 12 months was reported by two studies for MI (Haskell 1994; WHO 1983), one study for CABG (Ståhle 1999) and two studies for PTCA (Haskell 1994; Ståhle 1999). There was no statistically significant difference between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation and usual care for these outcome measures. The pooled risk ratios for total MI, CABG and PTCA were 0.92 (95% CI 0.70, 1.22), 0.91 (95% CI 0.67, 1.24) and 1.02 (95% CI 0.69, 1.50), respectively, up to 12 months follow-up. In studies reporting follow-up longer than 12-months, the pooled risk ratios for total MI, CABG and PTCA were 0.97 (95% CI 0.82, 1.15), 0.93 (95% CI 0.68, 1.27) and 0.89 (95% CI 0.66, 1.19) respectively. There was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity across trials for any of the morbidity outcomes.

Hospitalisations

Ten (N = 2379) of the included studies reported hospital admissions; one study reported both follow-up to 12 months and longer than 12 months (Hofman-Bang 1999). In studies reporting up to 12 months follow-up, total readmissions were reduced with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation compared with usual care (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51, 0.93; Analysis 1.6). There was no significant difference in total hospitalisations in studies with follow-up longer than 12 months.

Health-related quality of life

Ten trials assessed health-related quality of life using a range of validated disease-specific (e.g. QLMI) and generic (e.g. Short-form 36) outcome measures (Table 1). Given both the heterogeneity in outcome measures and methods of reporting findings, a meta-analysis was not undertaken.

Although most trials demonstrated an improvement in baseline quality of life following exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation, a within group improvement was also often reported in control patients. Only in seven out of 10 trials was there evidence of a significantly higher level of quality of life with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation than control at follow-up (Belardinelli 2001;Dugmore 1999; Sivarajan 1982; Yu 2004).

Costs

Three of the included studies reported limited data on costs per patient (Kovoor 2006; Marchionni 2003; Yu 2004). These results are summarised in Table 2. It was not possible to compare the costs directly across studies due to differences in currencies and the timing of studies.

In two of the three studies the total healthcare costs associated with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation and usual care were not statistically significantly different. In Marchionni 2003, the total healthcare costs associated with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation were higher ($4839 more per patient) than usual care.

Only Oldridge 1991 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in post-MI patients by combining cost information with time trade-off measures of health-related quality of life and data on mortality derived from a 1989 meta-analysis (O’Connor 1989). Based on their analysis, the authors concluded that rehabilitation was “an efficient use of health-care resources and may be economically justified” (Oldridge 1993).

Meta regression

Predictors of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, recurrent MI, and revascularisation (CABG and PTCA) were examined using univariate meta-regression. Covariates defined a priori included: CHD case mix (myocardial infarction-only trials versus other trials); type of cardiac rehabilitation (exercise-only versus comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation); ‘dose’ of exercise intervention (calculated as the number of weeks, multiplied by the number of sessions per week, multiplied by the duration of sessions in hours); follow-up period (≤ 12 months versus > 12 months); and publication date (before 1995 versus 1995 or later). No statistically significant associations were seen in any of these analyses (Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main results

This updated systematic review of exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation has allowed analysis of an increased number of patients from an additional 17 studies published from 2000 to 2009. A total of 47 RCTs, with 10,794 patients, have now been included. In accord with the original Cochrane review and previous metaanalyses (Clark 2005; Jolliffe 2001; O’Connor 1989; Oldridge 1988) a reduction in both total and cardiac mortality was observed in CHD patients randomised to exercise-based rehabilitation. However, this updated review shows that this mortality benefit is limited to studies with a follow-up of greater than 12 months. We also found that with exercise the rate of hospital readmissions may be reduced in studies up to 12 months follow-up (based on 4 trials with 54/254 versus 73/225 events), but not in longer term follow-up. There was no difference between exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation and usual care groups in the risk of recurrent myocardial infarction or revascularization at any duration of follow-up.

This reduction in total and cardiovascular mortality with exercise therapy appears consistent across a number of CHD groups (e.g., post-MI, post-revascularisation), as well as a range of strategies for delivery of the exercise-based intervention. We compared trials that assessed exercise therapy alone with exercise in combination with educational and psychological co-interventions and there appears to be no difference in mortality effect. In addition, there was no difference in mortality effect by exercise ‘dose’ a composite measure based on the overall duration of the exercise program plus the intensity, frequency, and length of exercise sessions.

The mechanism for reduced cardiovascular mortality in patients who have received exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is not clear, but may be due to improved myocardial revascularisation, protection against fatal dysrhythmias, improved cardiovascular risk factor profile, improved cardiovascular fitness, or increased patient surveillance (Oldridge 1988; Taylor 2006).

There were insufficient data to definitely definitely conclude that exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation improves health-related quality of life compared to control. Only 10 of included trials reported outcomes based on a validated health-related quality of life measure. Furthermore, only three of these 10 trials randomised more than 250 patients; thus, providing relatively adequate power (80% and 5% alpha) to detect a modest difference (standardised effect size of 0.25) between exercise therapy and usual care. Heterogeneity of health-related quality of life outcome measures and their reporting precluded us from quantitatively pooling the available data across trials. Generic health-related quality of life measures that lack sensitivity to change with cardiac treatment, particularly in comparison with disease-specific measures, were used in nearly all the trials (Oldridge 2003; Taylor 1998).

All participants in the included studies had documented CHD, the majority of the participants having suffered an MI. Some participants had documented CHD having suffered angina or undergone coronary angiography, while others had undergone CABG. We have combined these different patient groups as there are insufficient data at present to stratify trials by type of CHD. The number of women participants was low and few studies mentioned the ethnic origin of their participants. The mean age of the participants was 56 years. Although most studies had an upper age limit of at least 65 years of age, this is not reflected in the mean age of the participants. The majority of the studies had exclusion criteria that would have excluded those participants who had co-morbidity, or heart failure. In some studies this may have accounted for up to 60% of the patients considered for the trial, and certainly the older patients would be more likely to be affected.

Quality of the evidence

We found no evidence of publication bias for total mortality, CV mortality, CABG or PTCA. There was evidence of small study bias for total MI.

As with the original Cochrane review, this update review has revealed limitations in the available RCT evidence, most notably the poor reporting of methodology and results in many trial publications (Jolliffe 2001). The method of randomization, allocation concealment, or blinding of outcomes assessment was rarely described. Although the quality of reporting tends to be poorer for older studies, it does not appear to have appreciably improved over the last decade. Furthermore, incomplete outcome data (primarily due to losses to follow-up or dropouts) were insufficiently addressed in most trials. Losses to follow-up were relatively high across trials (approximately one third of trials reported a greater than 20% loss to follow-up) but reasons for dropout were often not reported. Several trials excluded significant numbers of patients post-randomisation, and thus in an intention-to-treat analysis, these patients have been regarded as dropouts. This may be partly explained by the fact that the majority of trials were not designed to assess treatment group differences in mortality and morbidity but instead surrogate measures of treatment efficacy, such as exercise capacity or lipid levels.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

In medium to longer term (i.e. 12 or more months follow-up) exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is effective in reducing overall and cardiovascular mortality and appears to reduce the risk of hospital admissions in the shorter-term (< 12 months follow-up) in patients with CHD. The available evidence does not demonstrate a reduction in the risk of total MI, CABG or PTCA with exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation as compared to usual care at any duration of follow-up. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation should be recommended for patients similar to those included in the randomised controlled trials - predominantly lower risk younger men who had suffered myocardial infarction or are post-revascularisation. It is a question of judgement whether evidence is sufficient to under-represented groups, particularly angina pectoris and higher risk CHD patients and those with major co-morbidities. There appears to be little to choose between exercise only or in combination with psychosocial or educational cardiac rehabilitation interventions. In the absence of definitive cost-effectiveness comparing these two approaches to exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation it would be rational to use cost considerations to determine practise.

Implications for research

In spite of inclusion of recent trial evidence including more post-revascularisation and female patients, the population of CHD patients studied in this review update remains predominately low risk middle-aged males following MI or PTCA. There has been little identification of the ethnic origin of the participants. It is possible that patients who would have benefited most from exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation were excluded from the trials e.g. those of older age or those with co-morbidity. Therefore, well-designed, and adequately reported RCTs in groups of CHD patients more representative of usual clinical practice are still needed. These trials should include validated health-related quality of life outcome measures, need to explicitly report clinical events including hospital admission, and assess costs and cost-effectiveness.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Regular exercise or exercise with education and psychological support can reduce the likelihood of dying from heart disease

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is one of the most common forms of heart disease. It affects the heart by restricting or blocking the flow of blood around it. This can lead to a feeling of tightness in the chest (angina) or a heart attack. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation aims to restore people with CHD to health through either regular exercise alone or a combination of exercise with education and psychological support. The findings of this review indicate that exercise-based rehabilitation reduces the likelihood of dying from heart disease and there is moderate evidence of an improvement in quality of life in the predominantly middle aged, male patients included in these studies. More research is needed to assess the overall health impact of exercise-based rehabilitation in a broader range of patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Lambert Felix and Philippa Davies for examining the titles and abstracts of citations identified by the electronic searches for possible inclusion.

We would also like to thank Sue Whiffen for her administrative assistance and Nizar Abazid, Ela Gohil, Ellen Ingham, Cornelia Junghans, Joey Kwong, Dan Manzari, Fenicia Vescio, and Gavin Wong for their translation services.

We would like to thank all the authors who provided additional information about their trials.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

NIHR, UK Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant, UK.

This review was supported by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant (CPGS10).

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Post MI randomised four weeks after discharge. 88 participants were randomised, but 13 failed to follow up. Therefore 75 took part in the study | |

| Participants | 75 men < 66 yrs with 1st MI. Mean age I = 52.2 (+/−7.5), C= 55.6 (+/−6.3). |

|

| Interventions | Aerobic activity e.g. running, cycling, skipping + weights for 1 hour × 2 weekly for 2 months, then × 1 week for 10 months. Then continue at home. F/U @ 1, 13, 25, & 37 months post discharge. |

|

| Outcomes | Total & CHD mortality and non fatal MI. | |

| Notes | Several participants in C trained on own initiative, but were analysed as intention to treat. Authors concluded that PT after MI appears to reduce consequences and to improve PWC, but PWC declines once participant on their own. PT had no effect on period of convalescence or return to work, but age and previous occupation were of significance |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “random numbers” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 15% lost to follow-up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | RCT, single centre in Italy 33 (SD 7) months |

|

| Participants |

N Randomised: Total:118 (99 males, 19 females); EX: 59 (49 males, 10 females) UC: 59 (50 males, 9 females) Diagnosis (% of pts); Myocardial Infarction: EX 51; UC 47 Hypercholesterolemia: EX 61; UC 54 Diabetes: EX 17; UC 20 Hypertension: EX 42; UC 47 LVEF (%): EX 52 (SD 16); UC 50 (SD 14) Case mix: Age (years): EX: 53 (SD 11); UC: 59 (SD 10) Percentage male: EX 83.1%; UC 84.8% Percentage white: Not reported Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: successful procedure of coronary angioplasty in 1 or 2 native epicardial coronary arteries and ability to exercise Exclusion: previous coronary artery procedures, cardiogenic shock, unsuccessful angioplasty (defined as residual stenosis>30% of initial value), complex ventricular arrhythmias, uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes mellitus, creatinine ?2.5 mg/dl, orthopedic or neurological limitations to exercise or unstable angina after procedure and before enrolment |

|

| Interventions |

Exercise:

Total duration: six months aerobic/resistance/mix: exercise sessions were performedat the hospital gym and were supervised by a cardiologist frequency: 3 sessions/week duration: 15 min of stretching and callisthenics; 5 min of loadless warm-up; 30 min of pedaling on electronically braked cycle ergometer at target work rate; 3 min of unloaded cool-down pedaling intensity: 60% of peak oxygen uptake (VO2) modality: electronically braked cycle ergometer Usual care: “Control patients were recommended to perform basic daily mild physical activities but to avoid any physical training.” |

|

| Outcomes | Cardiac mortality; myocardial infarction; coronary angioplasty (percutaneous translu-minal coronary angioplasty, coronary stent); coronary artery bypass graft; health-related quality of life: MOS Short-Form General Health Survey | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | “All studies were performed by

experienced operators and evaluated

by two independent observers blinded

to treatment arm and to each otherls interpretation. ” Comment: This only applied to exercise test & angiography only so assessment of events and health-related quality of life (although patient self complete) not necessarily blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Cardiac events of 12 patients who were excluded not accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Post MI Randomised 4-6 days post event. |

|

| Participants | 311 men / 89 women < 65 yrs. Mean ages for women 60.7 (+/− 7.2) to 64.3 (+/−7.3), for men 57.8(+/− 8.9) to 59.4 (+/− 9.4). 2 comparisons conventional CR v: the Heart Manual (HM) and HM v: control |

|

| Interventions | Conventional CR - 1 to 2 group classes per week, walking etc other days for 8-12 weeks with multidisciplinary team HM - individual - walking programme up to 6 weeks post MI, facilitator and written text. F/U - 1 year. |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, health-related quality of life: Nottingham Health Profile | |

| Notes | “Heart Manual is a comprehensive home based programme which included an exercise regimen, relaxation and stress management techniques, specific self-help treatments for psychological problems commonly experienced by MI patients and advice on coronary risk-related behaviours.” Hospital readmissions significantly reduced in Heart Manual group compared with conventional CR and control in initial 6 month period |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomisation was achieved by providing each hospital with a series of sealed envelopes containing cards evenly distributed between conditions. The envelopes were taken sequentially and, before opening the envelope, the patient’s surname was written diagonally across the sealed flap, in such a way that when the envelope was opened the name was ‘torn in two’. Opened envelopes were retained and returned to the trial coordinator. The importance of remaining neutral when advising the patients of the outcome of randomisation was emphasised in the written protocol and was reinforced during the sessions which were held to familiarise facilitators with the protocol.”” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “Randomisation was achieved by providing each hospital with a series of sealed envelopes containing cards evenly distributed between conditions. The envelopes were taken sequentially and, before opening the envelope, the patient’s surname was written diagonally across the sealed flap, in such a way that when the envelope was opened the name was ‘torn in two’. Opened envelopes were retained and returned to the trial coordinator. The importance of remaining neutral when advising the patients of the outcome ofrandomisation was emphasised in the written protocol and was reinforced during the sessions which were held to familiarise facilitators with the protocol.” Comment: Patients were informed of outcome of randomisation. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | 1.5% lost to follow up and reported description of withdrawals and/or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | RCT; single centre Sweden; F/U 14 months average | |

| Participants | N=87 (EX n= 44; CON n=43) Gender: 74 men / 13 women Mean age: EX = 55.3 +/− 6.6, CON = 57.1 +/− 6.6. Diagnosis: following acute MI. Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: <65 years with MI Exclusion: decisions based on cardiologist: severe cardiac failure, PMI-syndrome, aortic regurgitation, cerebral infarct hemiparesis, disease of hip, status post-poliomyelitis, amputation of lower extremity, Diabetes with retinopathy, hyper/hypo thyroidism, hyper-parathyroidism, mental illness |

|

| Interventions | Exercise intervention: Duration: 3 months; Frequency: 30 min twice weekly. Mode: physical training, interval training of large muscle groups, jogging, callisthenics Co-interventions: counselling, social measures, group and individual. Intensity: graded individually |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, CHD mortality, non-fatal MI up to average 14 months | |

| Notes | Most emphasis on social/ psychological aspects. 171 patients were randomised and at discharge the cardiologist decided whether the patient was fit to take part in the rehab programme - 45 patients were excluded at this point. 7 of intervention group declined to take part, but 6 of these were seen at follow up and included in the analysis because “control group probably had a comparable number who would have declined further treatment.” |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “allocated at random” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | Description of withdrawals & dropouts: 29% I, 33% C lost to follow up from 126 who took part. 171 were randomised and then 45 excluded by cardiologist |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Randomised on day of discharge after MI; F/U 12-24 months. | |

| Participants | N = 110 (EX n:57; CON n:53) Gender: NR Mean age: EX = 52.1 +/− 1.3, CON = 52.7 +/− 1.3 Diagnosis: <65 yrs with acute myocardial infarction confirmed by typical symptoms, electrocardiographic changes, and a rise in cardiac creatinine kinase isoenzyme Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: Men and women with acute myocardial infarction and had been admitted to Plymouth coronary care unit Exclusion: uncontrolled heart failure; serious rhythm disturbances which persisted and required treatment at time of discharge; another disabling disease |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group: Duration: 4 weeks; Frequenty: 2 × week; Mode: standard pulse-monitored group exercise commonly used in the physiotherapy ofcardiac patients, 12 station circuit started 3 weeks post discharge Control: standard hospital care |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, non fatal MI, revascularisation; Assessments at day ofdischarge, 3rd week after discharge; after rehabilitation (for intervention group); four months after infarct and 12-24 months after infarct) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomised” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 24% lost to follow-up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Parallel RCT; single centre in Alton, Hampshire | |

| Participants | N: 200 (EX n=99; CON n101=) Gender: 100% men Age: EX = 54.2 (+/−7.2), CON = 53.2 (+/−7.7). Diagnosis: 5 days post MI. Ethnicity:NR Inclusion: <65 yrs post MI; history of chest pain typical of MI, progressive ECG changes, rise and fall in aspartate transaminase concentrations with at least one reading above 40 units/ml Exclusion: medical or orthopaedic problems that precluded their taking part in the exercise course; insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; atrial fibrillation; on investigator’s personal general practice list |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group: Duration: 3 months; Frequency: 3×/week; Mode: 8 stage circuit aerobic & weight training. Intensity: 70-85% predicted HRmax Control group: given a short talk on the sort of exercise that they might safely take unsupervised |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, CHD mortality, non fatal MI (11 year follow up published in 1999. 5 year follow up data from unpublished material used for meta analysis.) | |

| Notes | 229 patients were randomised; 14 in the intervention group and 15 in control dropped out before the first exercise test due to death, refusal or other problems. Therefore 200 took part in the study Cardiac mortality of 3% pa, once patients survived to be in the trial. Suggests more severely affected patients were not included. Significant predictors of cardiac death were pulmonary oedema on admission, complications during admission, one or more previous infarcts, increasing age and low initial fitness |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | random letter sequence |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 16% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Parallel RCT, single centre in Sweden | |

| Participants | N= 37 randomised (EX n=21; CON n=16) 86.5% male. Age 63.6 years Diagnosis: stable CAD and coronary angiographic changes. Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: coronary artery stenosis documented by angiography or previous coronary artery bypass grafting, classes I-III angina pectoris, classified according to Canadian Cardiovascular Society Exclusion: disabling disease that hindered regular exercise, or if the patient already has engaged in exercise more than 3 days/week |

|

| Interventions | Ttraining - high frequency exercise- group: 3 endurance resistance exercises and trained on a bicycle ergometer 30 min, 5 times a week for 8 months at 70% ofV02max. Duration: 8 months | |

| Outcomes | PTCA at 2 months before PCI and 6 months after PCI | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomised” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 8.1% lost to follow-up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | RCT; single-centre in Sweden; F/U 1 year | |

| Participants | N= 235 (EX n=118; CON n=117) Diagnosis: AMI or CABG (4 weeks post discharge); CABG (n = 67); AMI (n = 168) Mean age: AMI patients I = 62.2 +/−5.8, C= 61.7 +/−6, CABG patients Mean age I = 62.7 +/− 4.8, C= 59.8 +/− 4.8. Ethnicity: NR Inclusion:Acute MI; coronary artery bypass revascularization surgery less than 2 weeks prior; PTCA less than 2 weeks prior Exclusion: signs of unstable angina; signs of ST-depression at exercise test of more than 3 mm in 2 chest leads or more than 2mm in two limb leads at four weeks post discharge from hospital, signs ofCHF, severe, non-cardiac disease; drinking problems, not Swedish spoken |

|

| Interventions | Exercise programme: Duration: 2-3 months; Frequency: 2-3 × weekly Session duration: 60 mins; Mode: walking and jogging followed by relaxation and light stretching exercises; Nurse counselling: 9 hours of counselling in individual & group sessions over 1 year; smoking cessation 1.5, dietary management 5.5 & physical activity 2 hours Control: usual care |

|

| Outcomes | Mortality, | |

| Notes | Groups of 20 patients randomly allocated to intervention and control groups (usual care) . Randomised 4 weeks post discharge In first 3 weeks post discharge all participants ( I & C) had 2 visits by nurse & 1 by cardiologist + all participants invited to join regular exercise group × 1 per week for 30 mins information & 30 mins easy interval training |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | <20% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Randomised 6 weeks post admission | |

| Participants | N: 303 (EX n=151; CON n=152) 100% men Mean age: EX = 50.3 (SE 0.65) years CON =52.8 (SE 0.67) years Diagnosis: MI Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: MI patients admitted to the coronary care unit; diagnosis based on ECG changes and /or elevation of serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase or lactic dehydro-genase taken on three consecutive days ExclusIon: >70 years; heart failure at follow-up clinic; cardio-thoracic ratio exceeding 59%; severe chronic obstructive lung disease; hypertension requiring treatment; diabetes requiring insulin; disabling angina during convalescence; orthopaedic or medical disorders likely to impede progress in the gym, personality disorders likely to render patient unsuitable for the course |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group: Duration: 12 weeks; Frequency: attended gym 2 × weekly : Mode: Exercises arranged on a circuit basis and pure isometric exercise was avoided. Control group: Did not attend gym |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, non fatal MI at 5 months, 1 year, 2 year and 3 year after MI (mean F/U 2.1 years) | |

| Notes | There appears to be a reduction in mortality in exercise participants with inferior MI | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomly allocated” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 21% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Randomised 3rd day post MI. | |

| Participants | 294 men & 8 women F <70 yrs (mean age 57+/− 8), post MI, in 5 centres | |

| Interventions | Nurse managed, home based, multifactorial risk factor intervention programme with exercise training based on De Busk/Miller. F/U 12 months | |

| Outcomes | Total mortality | |

| Notes | Levels of psychological distress dropped significantly for both groups by 12 months | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomly allocated” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 33% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals & dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | single-centre RCT in UK; f/u 5 yrs | |

| Participants | N=124 (EX n=62; CON n=62) Gender: 122 men Mean age: EX=54.8 y ;CON = 55.7 y Diagnosis: clinically documented MI between 1984 and 1988 Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: MI according to conventional WHO cardiac enzyme and ECG criteria ofMI Exclusion: NR |

|

| Interventions | EX : Duration: 12 months; Frequency: 3 times weekly; Mode: regular aerobic and local muscular endurance training , consisting of warm up and cool down exercises, sit ups, wall bar/bench step ups, cycle ergometry, and major component centered on training of aerobic capacity, using walking and jogging Control: “received no formal exercise training throughout the same 12 month period” |

|

| Outcomes | CV mortality; nonfatal MI; QoL at 4, 8, 12 months | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomly allocated” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | All patients accounted for. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Single-centre open RCT in Finland | |

| Participants |

N Randomised: Total: 228 (201 males, 27 females); EX: 119 (104 males, 15 females) UC: 109 (97 males, 12 females) Baseline Characteristics: Previous unstable angina (%): EX: 29; UC: 31 Previous MI (%):EX: 42; UC: 46 Hypertension (%):EX 31;UC 23 LVEF (%):EX: 70.3 (SD 11.5); UC: 71.4 (SD 12.3) Age (years): EX: 54.1 (SD 5.9); UC: 54.3 (SD 6.2) Percentage male:88% Percentage white: Not reported Inclusion/exclusion criteria: Inclusion: patients who underwent elective CABS Exclusion: any other serious disease; ?65 years of age |

|

| Interventions | 4 stage rehab over 30 months starting pre CABG with meeting of physician, psychologist and OT/PT. 6-8 weeks post CABG - 3 weeks IP with group sessions with psychologist, aerobic physical activity, relaxation & group discussion. 8 months post CABG - 2 days meeting with OT, nutritionist, physician, physio. 30 months post CABG - one day with nutritionist, physician & exercise. |

|

| F/U I year & 6 years Usual care: no further details |

||

| Outcomes | Mortality, CABG, health-related quality of life: Nottingham Health Profile | |

| Notes | 5 years after CABG only 20% of participants were working, despite 90% of patients being in functional classes 1-2. Almost half of patients had retired pre CABG. Many other factors affect RTW post CABG - age, education, physical requirements of the job, type of occupation, self employed status, non work income, personality type, self perception of working capacity and mostly length of absence from work pre CABG | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

High risk | “open randomised trial” Data on deaths &admissions from the hospital records department |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 13% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Single centre RCT in Rotterdam; Follow up 5 years. | |

| Participants | N= 80 (EX n=; CON n=) Gender: 100% male Mean age: 51years (range 35-60 years) Diagnosis: within 6 months post MI. Also with CABG/angina. Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: First MI within 6 months before the first psychologic investigation; <65 years; meet three psychologic inclusion criteria - one or more symptoms of the anxiety reaction, diminished self-esteem, positive motivation to take part in the programme Exclusion: severe cardiomyopathy, severe valvular disorders, inadequate performance on exercise, unstable angina pectoris |

|

| Interventions | Exercise intervention: duration: 6 months: Frequency: once per week; Session duration and mode: warming up period (15min), gymnastics and jogging (both 15 mins), sports such as volleyball, soccer, and hockey (30min), relaxation exercise (5min) Controls:Usual care plus educational brochure with guidelines about physical fitness training |

|

| Outcomes | Mortality, non fatal MI at 5 years | |

| Notes | Complex presentation of results. Authors conclude that patients who will benefit from rehab can be detected on psychological grounds. Those who have engaged in habitual exercise, but feel seriously disabled, yet do not feel inhibited in a group will benefit from rehab |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “randomly allocated by means of a table for random numbers” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 29 % lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Prospecitve, single centre RCT in the US. F/U 6 months. | |

| Participants | N= 88 (EX n=41; CON n=47) 100% male Mean age: EX= 62 +/−8, CON = 63 +/−7; (range 42 - 72) Diagnosis: CAD and a physical disability Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: ≤73 years; CAD and physical disability. CAD documented by history of MI, coronary artery bypass surgery, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty or angiographically demonstrated CAD; have the functional use ofmore than 2 extremities, 1 being an arm, in order to perform the exercise test and training protocols Exclusion: uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes mellitus, clinically significant cardiac dysrhythmias, unstable angina pectoris, cognitive deficits, or other problems that would interfere with compliance to the prescribed exercise and diet protocol |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group (Home exercise training programme): Duration: 6 months; Frequency: 5 days/week; Session duration: 20mins/day; Intensity: 85% of predicted maximal heart rate Mode: stationary wheelchair ergometer Control group: routine care |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, non fatal MI at 6 months | |

| Notes | The treatment programme decreased myocardial oxygen demand. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomized” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | “The same experienced cardiologist interpreted all echocardiograms and was unaware of randomization procedures” |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 32% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Single centre RCT in Sweden. F/U 1 & 5 years. | |

| Participants | N=178 (EX n=87; CON n=91) randomized N=116 (EX n=53; CON n=63) participated in the 1year F/U Gender: 101 men & 15 women Mean age: EX=55 years CON=57.6 years Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: 65 years or younger at the time of MI; independent living in the Health Care District after discharge from hospital; meaningful communication and rehabilitation that was not hindered by the MI or other serious illness Exclusion:cerebral or cardiac disorders or serious alcohol abuse |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group: Duration: 6months; Frequency: 1 weekly; Session duration: 2hrs; Mode: 1 hours exercise + 1 hours group discussion led by nurse Control: routine cardiac follow-up |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, non fatal MI, revascularisations | |

| Notes | Positive long term effects on physical condition, life habits, cardiac health knowledge. No effects found for cardiac events or psychological condition |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomly subdivided” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 32% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Parallel single centre RCT in Italy; 6 month F/U | |

| Participants | N=61 (EX n=30; CON n=31) 72.1% male. Mean age: EX=55.9 years; CON=55.1 years Diagnosis: post-infarction Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: acute ST elevation MI Exclusion: residual myocardial ischemia, severe ventricular arrhythmias, AV block, valvular disease requiring surgery, pericarditis, severe renal dysfunction (creatinine >2.5 mg/dL) |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group: Duration: 6 month; Frequency: 3×/week; Session duration: 30 min; Mode: bicycle ergometer; Intensity: target of60-70% ofVo2 peak achieved at the initial symptom-limited cardiopulmonary exercise test Control group: discharged with generic instructions to maintaining physical activity and a correct lifestyle |

|

| Outcomes | Fatal/non-fatal MI (6month F/U) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | “randomized” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not reported. |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | The physician performing all Doppler-echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise tests was unaware of the results of blood sampling and was blinded to the patient allocation into the study protocol Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

Low risk | All patients were accounted for. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Multicentre parallel RCT (4 centres in US) ; F/U 4 years | |

| Participants | N=300 (EX n=145; CON n=155) Gender: 259 men & 41 women Mean age: EX = 58.3 =/− 9.2, CON = 56.2 +/− 8.2. Diagnosis: CAD Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: < 75 years; clinically indicated coronary arteriography. After arteriography, patients received PTCA or CABG and remained eligible if at least one major coronary artery had a segment with lumen narrowing between 5% and 69% that was unaffected by revascularization procedures Exclusion: severe congestive heart failure, pulmonary disease, intermittent claudication, or noncardiac life-threatening illnesses; no qualifying segments, medical complication occurred during angiography, left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 20%, or patient was in another research study |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group (risk reduction group): Intructed by dietitian in a low-fat, low-cholesterol, and high-carbohydrate diet with a goal of <20% of energy intake from fat, <6% from saturated fat, and <75mg of cholesterol per day. Physical activity program : increase in daily activities such as walking, climbing stairs, and household chores and a specific endurance exercise training program with the exercise intensity based on the subject’s treadmill exercise test performance. (Nurse managed, home based programme based on Miller, with specific goals to be attained) Control group: usual care F/U 4 years. |

|

| Outcomes | Total & CHD mortality, non fatal MI, revascularisation at yr 1, 2, 3 and 4 | |

| Notes | The rate of change in the minimal coronary artery diameter was 47% less in I than C. This was still significant when adjusted for age and baseline segment diameter (p=0.03) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | “stratified random numbers in sealed envelopes” |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | “stratified random numbers in sealed envelopes” |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes |

Unclear risk | Unclear in terms of assessment of outcomes. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes |

High risk | 18% lost to follow up, no description of withdrawals or dropouts |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No information reported. |

| Methods | Cluster randomised multi-centre study (hospitals in and around Newcatle, Australia); F/U of 6 months | |

| Participants | N=450 (EX n=213; CON n=237) 71% male Mean age: EX = 59 +/− 8, CON = 58 +/− 8 years Diagnosis: Ethnicity: NR Inclusion: <70 years with a suspected heart attack registered by the Newcastle collaborating centre of the WHO MONICA Project and discharged alive from hospital Exclusion: renal failure or other special dietary requirements and those considered by their physicians to have ‘endstage’ heart disease |

|

| Interventions | Exercise group: 3 packages to participant - 1st package: Step 1“Facts on fat” kit, together with walking programmme information (also (encouragement to walk in the form of a magnetic reminder sticker), and “Quit for Life” program for smokers. 2nd package: Step 2-3 “Facts on fat” kit; exercise log. 3rd package: Step 4-5 “Facts on fat” kit, together with information regarding local “Walking for Pleasure” groups Control group: usual care |

|

| Outcomes | Total mortality, health-related quality of life: QLMI Study outcomes assessed at 6 months |

|

| Notes | Low use of preventative services (dietary, anti smoking) by both groups. 10% of patients received rehab - mostly having had CABG. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Cluster randomisation by GP. |