Abstract

Current clinical approaches to melanoma diagnosis have not been associated with a decrease in mortality from this cancer. The components of the new approach presented are, first, a screening examination to look for any lesion that stands out because of being dark, different, or changing; second, when a single lesion is recognized to be of concern for any reason, that lesion is then evaluated in more detail utilizing the ABCDE criteria, with the “D” signifying “Dark” and not “6 mm Diameter” in this mnemonic; and, third, additional discussion of the “ugly duckling” sign and of the recognition of nodular melanomas. Since the Georgia Society of Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery was the first state or national society to endorse this approach, I refer to it as the Georgia approach.

Introduction

The number of yearly deaths from melanoma continues to increase, and the overall melanoma mortality rate is one of the few cancer mortality rates not on the decline [1,2]. These realities combined with increasing evidence of the lack of efficacy of the ABCDE criteria have necessitated ongoing efforts to enhance the earlier clinical detection of melanoma [3–8]. Most approaches to melanoma diagnosis have included some predominant emphasis or combination of emphases on recognition of changing lesions, recognition of outlier (“ugly-duckling”) lesions, and specific melanoma characteristics, with the most utilized criteria being the ABCDE criteria (“A” for “Asymmetry,” “B” for “Border irregularity,” “C for Color variation,” “D for 6 mm Diameter,” and “E” for “evolving lesions”) [8]. Many recently published strategies have rejected the diameter criterion as well as abandoned all or portions of the ABCDE mnemonic [3,5,9–12]. Many of these proposed strategies, including the “D” for “Dark” proposal I offered, have also added emphasis on recognition of darkness as a particular feature of concern in pigmented lesions [5,10–12]. I have recently reviewed the compelling rationale for both an increased emphasis on darkness and rejection of the diameter criterion in the clinical diagnosis of melanoma [13]. The Georgia approach to melanoma diagnosis uniquely incorporates many elements of these strategies in a complementary manner to increase the sensitivity of diagnosis of early melanoma [13,14] (Figure 1).

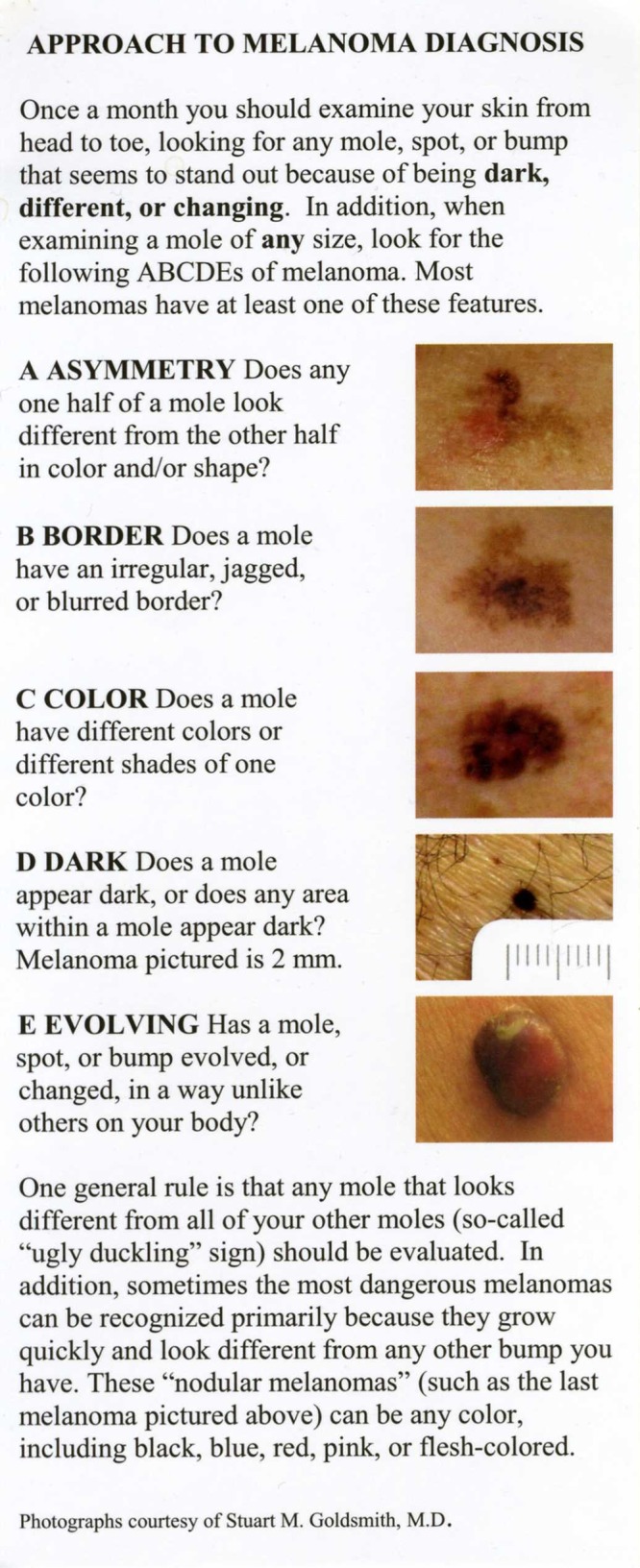

Figure 1.

The Georgia approach presented as a patient information card (actual card size is 8½ inches x 3½ inches). (Copyright: ©2014 Goldsmith et al.)

Discussion of the approach

First component: Screening examination for dark, different, or changing lesions

In their review of melanoma diagnosis, Marghoob and Scope discuss the concepts of a screening examination to identify lesions of possible concern and then the specific lesion assessment that follows [15]. This distinction is important because the screening examination determines the sensitivity of melanoma recognition, and it is the screening examination that really describes how most practitioners examine patients and how patients examine each other. First, the Georgia approach places increased emphasis on the screening examination by initial, distinct discussion and clarification of its function. Second, the approach includes both of the two screening strategies that have been used in most melanoma educational materials, change and ugly duckling identification. Third, the approach adds the easily perceived, easily communicated, highly sensitive, specific (compared to change and ugly duckling identification) screening feature of darkness. A major tenet of physical diagnosis, particular for early diagnosis, is that one sees what one looks for. A strategy based on recognition only of any lesion that changes or differs from other lesions inadequately considers this principle. The added benefit of looking specifically for dark lesions as part of a screening examination for melanoma cannot be overstated; many melanomas, particularly small melanomas, can be recognized because of, and only because of, their intensity of pigment [16].

Nonetheless, with melanoma, as with screening features for nearly every disease, no one feature has 100% sensitivity. The description of the screening examination for melanoma detection includes the instruction to examine the skin in order to detect any lesion that stands out because of being dark, different, or changing. Each of the three screening features has non-redundant as well as complementary importance in the recognition of melanoma. The screening examination should usually include two looks, one for any lesion that stands out at all, which should allow detection of changed or ugly duckling lesions, and a second look to identify lesions of any size that stand out because of appearing, even focally, dark. Consequently, the emphasis on darkness as a screening feature should only enhance the sensitivity of diagnosis of melanoma.

Second component: Application of the ABCDE criteria to specific lesions, either those lesions identified to be of concern on the screening examination or specific lesions being examined for any reason, with “D” for “Dark” in the ABCDE criteria

Though the impact of the ABCDE criteria on melanoma detection has been uncertain, the publication and utilization of these criteria are ubiquitous, and the criteria have many supporters. As Marghoob and Scope help elucidate, however, the role of the ABCDE criteria is not as a screening approach, as they have been utilized, but as a spot evaluation, and the criteria can also help to assess the level of concern when comparing similar lesions [15]. Thus, the criteria have value, but one that requires this more precise explanation. The meanings of the A, B, C, and E in the Georgia approach are unchanged from usual use: “A” for “Asymmetry,” “B” for “Border irregularity,” “C” for “Color variation,” and “E” for “Evolving” unlike other lesions. What is critical to the utility of the ABCDE criteria, however, is the change of the “D” to signify “Dark” and not “6 mm Diameter.” With this change, and without altering the familiar mnemonic, the criterion never present in the earliest melanomas is replaced by the single criterion that characterizes many early melanomas [11,16,17]. It can now be stated more accurately that most melanomas have one or more of the ABCDE criteria and that the criteria are relevant to the diagnosis of early melanomas. As a criterion of an individual lesion, similar to its utilization as a screening feature, the characteristic of darkness has non-redundant value and, in addition, enhances the application of other criteria.

Third component: Discussion of the “ugly duckling” rule and specific discussion of nodular melanoma recognition

There is increasing support for the strategy of melanoma recognition based on the concept that a melanoma will differ in appearance from one’s usual moles, referred to as the “ugly-duckling” rule. The possible utility in this concept is reflected in the Georgia approach both as a screening feature (“different”) and in the “E” for “Evolving” description (“Has a mole . . . changed . . . unlike others on your body?”). In the third component of the Georgia approach, the “ugly-duckling” sign is specifically defined, conveying additional emphasis on and understanding of this strategy and its application.

Nodular melanomas represent a minority of melanomas but contribute disproportionately to melanoma mortality, and the final portion of the Georgia approach is devoted to specific education about the diagnosis of this melanoma subtype. The varied presentations of nodular melanomas, including as amelanotic lesions, are specifically discussed, as is the particular relevance of change and ugly duckling recognition to the diagnosis of these melanomas. The inclusion of the nodular melanoma pictured adds further emphasis on both the diagnosis of nodular melanomas and of the relevance of change recognition to their diagnosis.

Nonetheless, as nodular melanomas have metastatic potential both in a shorter time frame and when smaller in diameter than other melanomas, the previously discussed addition of dark as a screening feature and the “D” for “Dark” change may have particular impact on decreasing mortality by enhancing the earlier diagnosis of this melanoma subgroup. In addition to the potential impact on the diagnosis of earlier nodular melanomas by removing any diameter consideration, many early nodular melanomas, similar to other melanoma subtypes, are characterized by their dark pigment [18,19].

Summary

Whatever changes occur in terms of melanoma diagnosis because of screening recommendations or technology, no strategy will reach its potential without the earliest possible clinical recognition of melanoma. The components of the Georgia approach accomplish the following:

First component: clarifies and emphasizes the role of a screening examination; adds dark to both change and ugly duckling identification as screening features; communicates the screening features simply and succinctly.

Second component: continues to utilize but more precisely defines the role of the ABCDE criteria and changes the meaning of the “D” to “Dark.”

Third component: discusses both the ugly duckling sign as a general rule as well as specific issues relevant to the diagnosis of nodular melanomas.

Each of these three components has non-redundant potential to enhance the diagnosis of melanoma. By unifying and integrating all of the components in a logical manner, however, the Georgia approach uniquely prioritizes and maximizes the sensitivity of diagnosis of early melanomas. During this period of transition in the clinical diagnosis of melanoma, I encourage other practitioners, departments, and societies to consider and adapt the Georgia approach, as well.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

References

- 1.Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Cancer.org Web site. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsstatistics/cancerfactsfigures2014/index. Accessed June 5, 2014.

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2013. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/, based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yagerman S, Marghoob A. The ABCDs and Beyond. The Skin Cancer Foundation Journal. 2013;31:61–3. , 94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maley A, Rhodes AR. Cutaneous melanoma: preoperative tumor diameter in a general dermatology outpatient setting. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:446–54. doi: 10.1111/dsu.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manganoni AM, Pavoni L, Calzavara-Pinton P. Patient perspectives of early detection of melanoma: the experience at the Brescia Melanoma Centre, Italy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2014 May 14; [Epub ahead of print] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson K, McIntosh RD, Bradley-Scott C, et al. Image training, using random Images of melanoma, performs as well as the ABC(D) criteria in enabling novices to distinguish between melanoma and mimics of melanoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(3):265–70. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Giorgi V, Papi F, Giorgi L, et al. Skin self-examination and the ABCDE rule in the early diagnosis of melanoma: the ABCDE rule in the early diagnosis of melanoma: is the game over? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1370–1. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yagerman S, Marghoob A. Melanoma patient self-detection: a review of efficacy of the skin self-examination and patient-directed educational efforts. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2013;13:1423–31. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2013.856272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yagerman SE, Chen L, Jaimes N, et al. ‘Do UC the melanoma?’ Recognising the importance of different lesions displaying unevenness or having a history of change for early melanoma detection. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:119–24. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luttrell MJ, Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Fink-Puches R, et al. The AC rule for melanoma: a simpler tool for the wider community. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:1233–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldsmith SM, Solomon AR. A series of melanomas smaller than 4mm and implications for the ABCDE rule. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:929–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shore RN, Shore P, Monahan NM, et al. Serial screening for melanoma: measures and strategies that have consistently achieved early detection and cure. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10:244–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsmith SM. Increased emphasis on darkness and rejection of a diameter criterion represent paradigm shifts in the clinical diagnosis of melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:474–6. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Website of the Georgia Society of Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery. gaderm.org, Accessed August 16, 2014.

- 15.Marghoob AA, Scope A. The complexity of diagnosing melanoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:11–3. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrari C, Seidenari S, Borsari S, et al. Dermoscopy of small melanomas: just a miniaturized dermoscopy? Br J Dermatol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/bjd.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bono A, Bartoli C, Baldi M, et al. Micro-melanoma detection. A clinical study on 22 cases of melanoma with a diameter equal to or less than 3 mm. Tumori. 2004;90:128–31. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bono A, Tolomio E, Carbone A, et al. Small nodular melanoma: the beginning of a life-threatening lesion. A clinical study on 11 cases. Tumori. 2011;97:35–8. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geller AC, Elwood M, Swetter SM, et al. Factors related to the presentation of thin and thick nodular melanoma from a population-based cancer registry in Queensland Australia. Cancer. 2009;115:1318–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]