Abstract

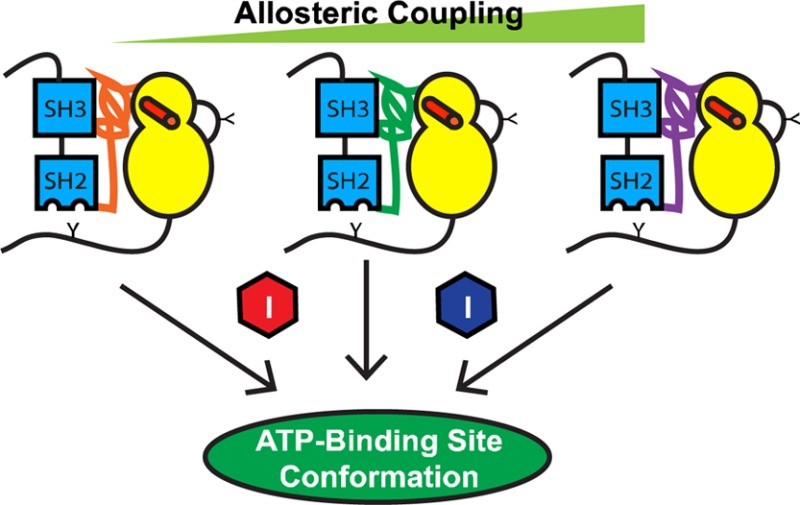

Src-family kinases (SFKs) make up a family of nine homologous multidomain tyrosine kinases whose misregulation is responsible for human disease (cancer, diabetes, inflammation, etc.). Despite overall sequence homology and identical domain architecture, differences in SH3 and SH2 regulatory domain accessibility and ability to allosterically autoinhibit the ATP-binding site have been observed for the prototypical SFKs Src and Hck. Biochemical and structural studies indicate that the SH2-catalytic domain (SH2-CD) linker, the intramolecular binding epitope for SFK SH3 domains, is responsible for allosterically coupling SH3 domain engagement to autoinhibition of the ATP-binding site through the conformation of the αC helix. As a relatively unconserved region between SFK family members, SH2-CD linker sequence variability across the SFK family is likely a source of nonredundant cellular functions between individual SFKs via its effect on the availability of SH3 and SH2 domains for intermolecular interactions and post-translational modification. Using a combination of SFKs engineered with enhanced or weakened regulatory domain intramolecular interactions and conformation-selective inhibitors that report αC helix conformation, this study explores how SH2-CD sequence heterogeneity affects allosteric coupling across the SFK family by examining Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2. Analyses of Fyn1 and Fyn2, isoforms that are identical but for a 50-residue sequence spanning the SH2-CD linker, demonstrate that SH2-CD linker sequence differences can have profound effects on allosteric coupling between otherwise identical kinases. Most notably, a dampened allosteric connection between the SH3 domain and αC helix leads to greater autoinhibitory phosphorylation by Csk, illustrating the complex effects of SH2-CD linker sequence on cellular function.

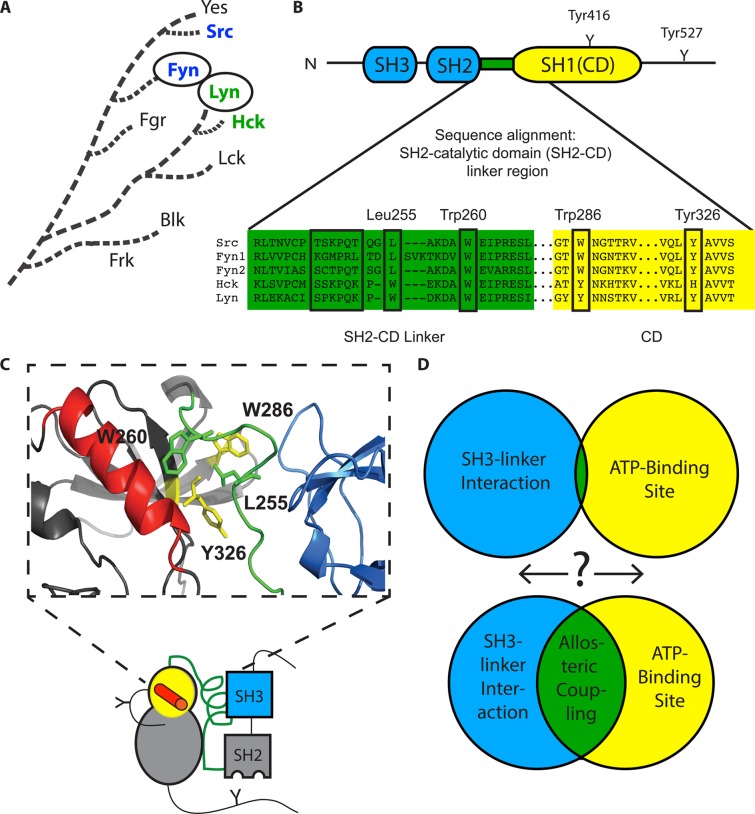

Src-family kinases (SFKs) make up a family of nine non-receptor tyrosine kinases (Src, Hck, Fyn, Lyn, Lck, Yes, Fgr, Blk, and Frk) that play a variety of important biological functions through both catalysis and intermolecular protein–protein interactions (Figure 1A).1,2 Largely because of the potential roles that they play in human disease, SFKs have become popular subjects of study, with most biochemical and structural research focusing on Src and Hck.2−4 All SFKs consist of an N-terminal unique domain, regulatory SH3 and SH2 domains, a catalytic domain (CD), and a C-terminal tail (Figure 1B). Catalytic activity in SFKs is regulated by a combination of post-translational modification (phosphorylation) and intramolecular protein–protein interactions.2,4 In the autoinhibited form, SFKs adopt a closed global conformation stabilized by intramolecular interactions between the SH3 domain and the SH2-CD linker [polyproline type II (PPII) helix] and between the SH2 domain and the C-terminal tail, which is enhanced by phosphorylation of Tyr527 on the C-terminal tail. In the active, open conformation, these intramolecular interactions are weakened and the regulatory domains are freed to interact with other binding partners in the cell. The active form is further stabilized by phosphorylation of the activation loop at Tyr416.5−10

Figure 1.

Allosteric relationships in the Src-family kinases (SFKs). (A) Dendrogram showing the evolutionary relationship of the Src-family kinases (SFKs). (B) Conserved domain architecture of SFKs. SH3 and SH2 regulatory domains are connected to the catalytic domain (CD) by the SH2-CD linker and C-terminal tail. The SH3 domain-binding epitopes in the linkers of Src, Fyn1, Fyn2, Hck, and Lyn are boxed, and key residues thought to allosterically connect the αC helix (ATP-binding site) and the SH3 domain are boxed and labeled (Src numbering). Note that Fyn1 has a linker longer than those of Fyn2 and Src. (C) Cartoon representation of the three-dimensional structure of an autoinhibited SFK. The crystal structure (PDB entry 2SRC) shows a portion of the CD (yellow), αC helix (red), SH2-CD linker (green), and SH3 domain (blue), known to be important for mediating allosteric connection of the ATP-binding site and regulatory domains. Key residues highlighted in panel B are shown as sticks. Of particular interest are the proximity of helix αC to Trp260 and the hydrophobic contacts made by Leu255. (D) Schematic illustrating the goal of this study, to probe the degree of bidirectional allosteric coupling between the ATP-binding site (helix αC) and the regulatory domains among SFK family members via the SH3–linker interaction.

Mutational studies and crystal structure analyses have shown that the SH2-CD linker region plays an important role in allosteric coupling between the ATP-binding site and the regulatory domains.11−17 Crystal structures of autoinhibited Src and Hck constructs show that a conserved Trp260 contacts the CD, near the αC helix, and forms a π-stacking/hydrophobic network with other aromatic residues contacting the SH3 domain, most notably Leu255 in Src (Trp255 in Hck) (Figure 1B,C).6,7,13,15 Mutating Leu255 to valine activates Src without disrupting binding between the SH2-CD linker and the SH3 domain, indicating that these interactions are mediating allosteric coupling between the ATP-binding site and regulatory domains.15 The conformation of helix αC is known to play a critical role in facilitating transitions between autoinhibited and active states.16 The proximity of the αC helix to Trp260 and its interaction with Leu255 indicate that it plays a role in transmitting changes in ATP-binding site conformation to the regulatory domains and vice versa. The allosteric relationship described above is bidirectional, in that ATP-binding site conformation also influences regulatory domain engagement.9,10 In fact, our lab has shown that ATP-competitive ligands that stabilize Src and Hck in an inactive αC helix-out conformation strengthen intramolecular SH3/SH2 domain engagement upon binding.12,18 In contrast, inhibitors that stabilize helix αC in an active conformation weaken interactions between the SH2/SH3 domains and their respective intramolecular ligands. While the basic allosteric regulatory network between the catalytic and regulatory domains of SFKs is well-characterized, less is known about how SH2-CD linker heterogeneity affects the magnitude of this bidirectional relationship. For example, we have observed differences in the relative magnitude of allosteric coupling between Src and Hck.12,18 Because of their overall structural homology, allosteric regulation in Src and Hck has been assumed to be the same in many studies. Differences in SH2 and SH3 domain availability for intermolecular associations could have unexplored biological consequences and help explain nonredundant functions of individual SFKs. Thus, a more thorough exploration of the SFK family is needed to understand how SH2-CD linker variability affects regulatory domain accessibility and ATP-binding site conformation.

The binding preferences of the SH2 and SH3 domains of SFKs are very similar, and their catalytic domains have almost identical substrate specificities in vitro; however, their sequences diverge at the SH2-CD linker.19−22 Hck and Src are evolutionarily disparate, occupying different branches of the tyrosine kinase portion of the kinome dendrogram (Figure 1A).19 SFKs have been characterized as “Src-like” or “Hck-like” with respect to their linker sequences (Src’s linker is one residue longer than Hck’s), and it has been proposed that variation in linker length or sequence may be a source of functional differences between these homologous family members (e.g., recruitment of different binding partners). In fact, global conformational differences, presumably caused by SH2-CD linker heterogeneity, between the two SFK subfamilies have been exploited with bivalent peptide inhibitors that target the CD and the SH2 domain.23 A bivalent ligand that is more than 1000-fold selective for Src-like SFKs (Src, Fyn, Yes, and Fgr) over Hck-like SFKs (Hck, Lyn, Lck, and Blk) has been generated, indicating a detectable difference in the relative proximity and accessibility between the SH2 domains and CDs in the two subgroups of SFKs. Furthermore, studies have shown that a chimeric SFK, made by swapping the SH3 domain of Src with that of Lck (Hck-like), displays impaired autoinhibition, while swapping the SH3 domains of Src and Fyn (both Src-like) results in a fully autoinhibited kinase.24,25 These data suggest that the SH3–SH2-CD linker interaction is tuned within each SFK subgroup and highlights the ability of the SH2-CD linker to determine the degree of allosteric coupling between the SH3 domains and the ATP-binding sites of SFKs.

Given the SH2-CD linker’s prominent role in SFK ATP-binding site–regulatory domain coupling and its relatively low level of sequence homology, we hypothesize that SH2-CD variability between SFKs produces differences in the magnitude of coupling between individual family members, even those belonging to the same subgroup. Such variation could have important cellular consequences and contribute to experimentally observed nonredundancy. To better understand how SH2-CD linker diversity leads to variability in SFK regulatory interactions, we explored the bidirectional relationship between the regulatory domains and CDs of the SFKs Fyn (Src-like) and Lyn (Hck-like). We also performed the same analysis on two splice variants of Fyn (Fyn1 and Fyn2), which contain divergent linkers within the context of nearly identical SH3, SH2, and CDs.26 Using a panel of conformation-selective, ATP-competitive inhibitors in combination with a panel of Fyn1, Fyn2, and Lyn regulatory state mutants, our study explores the degree of allosteric coupling between each regulatory domain and the ATP-binding site for each SFK (Figure 1D). Systematically profiling the effects of αC helix conformation on regulatory domain accessibility across the SFK family is necessary to explain how these highly homologous family members are able to perform nonredundant cellular functions and to provide insight into how allosteric regulation governs and adds complexity to the behavior of homologous multidomain protein kinases. Our study consists of two components: (1) exploration of how SH2 and SH3 domain engagement affects ATP-binding site conformation via the SH2-CD linker and (2) characterization of how αC helix conformation influences regulatory domain accessibility via the SH2-CD linker for Fyn1, Fyn2, and Lyn.

Materials and Methods

SFK Regulatory State Mutant Design and Protein Expression

QuikChange mutagenesis was used to introduce all point mutations. SFKY527F constructs: Lyn Y508F, Fyn1 Y531F, and Fyn2 Y528F. SFKSH2eng constructs: Lyn Q509E/Q510E/Q511I, Fyn1 Q532E/P533E/G534I, and Fyn2 Q529E/P530I/G531I. SFKSH3eng constructs: Lyn K233P/K236P, Fyn1 M251P/L254P/T255P, and Fyn2 T251P/T254P/S255P. Fyn active site cysteine constructs: Fyn1 S350C and Fyn2 S347C. The Src-family kinases Fyn1 (residues 82–537), Fyn2 (residues 82–534), and Lyn (residues 64–512) were expressed with YopH and GroEL and purified as previously described for Src and Hck.12,27 All constructs possess an N-terminal His tag to facilitate purification and a TEV protease cleavage site. All constructs were obtained in ≥95% purity. The CskDR plasmid was transformed into BL21(DE3) competent cells and purified by GST resin.

Preparation of Activation Loop-Phosphorylated SFK (pY416 SFK)12,18

SFK was autophosphorylated at Tyr416 by incubating SFK (250 nM) with ATP (1 mM) and BSA (1 mg/mL) in activation buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM EGTA, and 100 mM NaCl]. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 1.5 h. Quantitative phosphorylation was monitored with antibodies that specifically recognize activation loop-phosphorylated Src [1:2000 P-Src Family (Tyr416 DM9G4) Cell Signaling] and non-pTyr416 [1:2000 non-pY416 (7G9) Cell Signaling] (Figure S1 of the Supporting Information).

Substrate Km Determination

Peptide Substrate Km Determination

Activities of SFK regulatory state mutants in the presence of varying concentrations of the Src-peptide substrate (Ac-EIYGEFKKK-OH) were determined (3-fold dilutions starting at an initial concentration of 900 μM, seven data points) in assay buffer containing 75 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, 3.75 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mg/mL BSA, and [γ-32P]ATP (0.2 μCi/well) at room temperature and ambient pressure. The concentrations of SFK constructs were as follows: 0.7 nM LynAct, 0.3 nM Fyn1Act, 2.5 nM Fyn2Act, 10 nM LynSH2eng, 10 nM Fyn1SH2eng, and 3 nM Fyn2SH2eng. The final volume of each assay well was 30 μL. The enzymatic reaction was conducted at room temperature for 2 h and then terminated by spotting 4.6 μL of the reaction mixture onto a phosphocellulose membrane. Membranes were washed with 0.5% phosphoric acid (three times, 10 min each wash) and dried, and the radioactivity was determined by phosphorimaging with a GE Typhoon FLA 9000 phosphor scanner. The scanned membranes were quantified with ImageQuant. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, and Km values were determined using Michaelis–Menten analysis.

ATP Km Determination

Activities of SFK regulatory state mutants in the presence of varying concentrations of ATP were determined (3-fold dilutions starting at 500 μM, seven data points). Assay conditions are the same as those described above with 100 μM SPS added to the assay buffer solution. The concentration of [γ-32P]ATP was increased to 0.8 μCi/well, while the overall ATP concentration was varied using nonradioactive ATP. The concentrations of SFK constructs were as follows: 0.7 nM LynAct, 0.3 nM Fyn1Act, 2.5 nM Fyn2Act, 10 nM LynSH2eng, 10 nM Fyn1SH2eng, 3 nM Fyn2SH2eng, 5 nM LynSH3eng, 1.2 nM Fyn1SH3eng, and 2.2 nM Fyn2SH3eng. The scanned membranes were quantified with ImageQuant. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, and Km values were determined using Michaelis–Menten analysis.

Enzymatic Activity Determination

Titrations of SFK regulatory state mutants (2-fold serial dilutions starting at 20 nM, seven data points) were assayed in buffer containing 75 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 15 mM MgCl2, 3.75 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mg/mL BSA, [γ-32P]ATP (0.2 μCi/well), and 100 μM SPS. The final volume of each assay well was 30 μL. The enzymatic reaction was conducted at room temperature for 2 h and then terminated by spotting 4.6 μL of the reaction mixture onto a phosphocellulose membrane. Membranes were washed with 0.5% phosphoric acid (three times, 10 min each wash) and dried, and the radioactivity was determined by phosphorimaging with a GE Typhoon FLA 9000 phosphor scanner. The scanned membranes were quantified with ImageQuant and converted to percent activity. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (mean ± SEM; n = 3).

Activity Assays for Inhibitor Ki Determination12,18

Inhibitors (initial concentration of 10 μM, 3-fold serial dilutions, 10 data points) were assayed in triplicate against all SFK constructs. Assay conditions were the same as those described for enzymatic activity assays. Concentrations of SFK constructs are as described above for SPS Km determination. Assays of CskDR (25 nM) were performed using 100 μM CSKtide (KKKEEIYFFFG-NH2). Blot radioactivity was determined by phosphorimaging with a GE Typhoon FLA 9000 phosphor scanner. The scanned membranes were quantified with ImageQuant and converted to percent inhibition. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, and Ki values were determined using nonlinear regression analysis.

Pull-Down Assay for Determining SH3 Domain Accessibility12,18

Formation of the Kinase–Inhibitor Complex

The kinase of interest (100 nM) and mammalian lysate (0.2 mg/mL) were diluted in immobilization buffer [50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT (pH 7.5)]. A saturating amount of the inhibitor of interest (5 or 10 μM) was added to this kinase dilution. The mixture was allowed to incubate for 30 min before being loaded on the resin.

SH3 Pull-Down

Forty microliters of a 50% slurry of SNAP-Capture Pull-Down Resin (NEB) was placed in a microcentrifuge tube. The resin was washed (twice, 10 bed volumes) with immobilization buffer. A SNAP tag–polyproline peptide fusion (VSLARRPLPPLP) (10 μM) was loaded onto the resin at a final volume of 100 μL in buffer. The resin was rotated at room temperature for 90 min. After polyproline peptide immobilization, the resin was washed (twice, 10 bed volumes), and 100 μL of the kinase–inhibitor complex was loaded. The resin was allowed to shake at room temperature for 1 h. After incubation with the kinase–inhibitor complex, the flow-through was collected, and the resin was washed (three times, 10 bed volumes). To elute the retained kinase, 100 μL of 1× SDS loading buffer was added, and the beads were boiled at 90 °C for 10 min. All samples were separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and visualized by Western blotting using a His6-specific antibody [at a 1:5000 dilution (abm, HIS.H8)]. The scanned blots were quantified with LI-COR Odyssey software to determine the percentage of kinase retained on the resin on the basis of the loaded and eluted fractions (mean ± SEM; n = 3).

SH2 Pull-Down

Pull-downs were performed as described previously using resin displaying an SH2-binding peptide (EPQpYEEIPIYL).18

Phosphorylation of the Tyr527 Assay

Titrations of Fyn1S350C and Fyn2S347C starting at 35 nM (2-fold serial dilutions, four data points) were incubated with 50 μM pharmacophore 1 with 0.25 mg/mL BSA, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 0.5 mM DTT in activation buffer (pH 7.5). Following a 4 h incubation at room temperature, 25 nM CskDR was added and phosphorylation was initiated by the addition of [γ-32P]ATP (0.2 μCi/well). The final volume of each assay well was 30 μL. The enzymatic reaction was run at room temperature for 1 h and then terminated by spotting 4.6 μL of the reaction mixture onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were washed with 0.5% phosphoric acid (three times, 10 min each wash) and air-dried, and the radioactivity was determined by phosphorimaging with a GE Typhoon FLA 9000 phosphor scanner. The scanned membranes were quantified with ImageQuant, and data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (mean ± SEM; n = 3).

Results

Intramolecular Regulatory Domain Interactions Differentially Modulate the Catalytic Activities of Fyn1, Fyn2, and Lyn

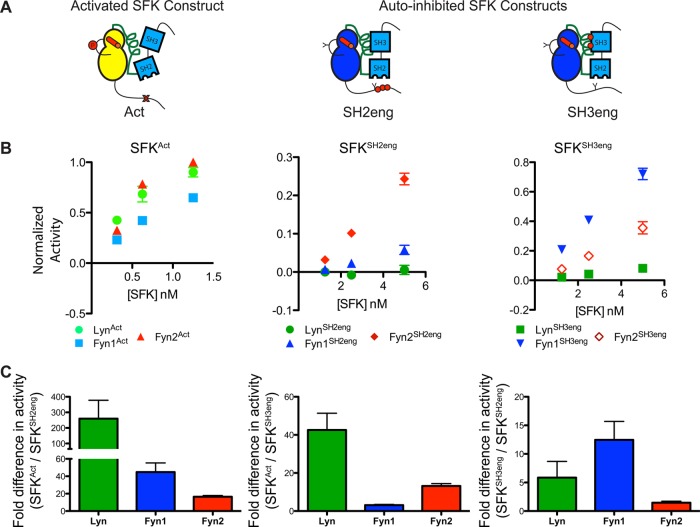

Autoinhibited and activated Src and Hck constructs have previously been generated by introducing mutations that enhance or weaken intramolecular SH2 and SH3 regulatory domain interactions. To explore the effects of SH2 and SH3 domain engagement on catalytic activity within the context of Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2, analogous regulatory state mutants of each SFK were generated (Figure 2A). All SFKs discussed in this work are three-domain (3D) constructs, meaning that they are full length except the unique domain has been excluded. Activated Lyn and Fyn (SFKAct) constructs were generated by activation loop autophosphorylation of Y527F mutants, which cannot undergo C-terminal tail autoinhibitory phosphorylation.28−30 Quantitative activation loop phosphorylation was confirmed via immunoblotting with antibodies that selectively recognize either phosphorylated or nonphosphorylated SFK activation loops (Figure S1 of the Supporting Information). Mutations that strengthen intramolecular SH2 and SH3 regulatory domain interactions were used to create autoinhibited Lyn and Fyn constructs. Constructs with an increased level of engagement between the C-terminal regulatory tail and the SH2 domain (SFKSH2eng) were generated by changing the three residues following Tyr527 to a high-affinity SH2 domain-binding epitope (Glu-Glu-Ile).31,32 Constructs with an increased level of engagement between the SH2-CD linker and the SH3 domain [SFKSH3eng (Figure S2 of the Supporting Information)] were generated by introducing two high-affinity PXXP motifs (PPXPP) into the SH2-CD linker (Figure S2 of the Supporting Information).33 This epitope has been shown to possess a similarly high affinity for the SH3 domains of SFKs.21,34−38 Adding PXXP sequences to the linkers of Fyn1, Fyn2, and Lyn enhances intramolecular SH3 domain engagement within the context of the native SFK linker, which has been shown in chimera studies to be tuned specifically for each SFK.24,25

Figure 2.

Intramolecular regulatory domain interactions affect the catalytic activities of Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2. (A) Cartoon representations of the SFK regulatory state mutants used in this study (SFKAct, SFKSH2eng, and SFKSH3eng). Disruptive mutations are illustrated as red X’s, while mutations that lead to greater intramolecular engagement are illustrated as red dots. (B) Activity of Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2 activated (left) and autoinhibited [SH2eng (middle) and SH3eng (right)] regulatory state mutants obtained via a radioactive phosphate transfer assay and plotted as signal vs enzyme concentration (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) Fold difference in activity between SFKAct and SFKSH2eng (left), SFKAct and SFKSH3eng (middle), and SFKSH2eng and SFKSH3eng (right) (mean ± SEM; n = 3).

The catalytic properties of all nine Lyn and Fyn constructs were tested in enzymatic assays. Interestingly, all nine constructs possess similar Km values for ATP (Table 1). In addition, the overall activation state of each SFK had only a small effect on the Km for the peptide substrate. Next, the relative catalytic activity of each construct was tested at an ATP concentration well below its Km. As expected, the SFKAct constructs are the most active, with Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2 demonstrating very similar catalytic activities (Figure 2B). This shows that, in the absence of intramolecular regulatory domain engagement, SFKs are functionally equivalent.

Table 1. Km Values for ATP and Src Peptide Substrate (SPS) Determined for Each SFK Regulatory State Mutant.

| SFK | Km(ATP) (μM) | Km(SPS) (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| LynAct | 42 ± 7 | 11 ± 2 |

| LynSH2eng | 54 ± 5 | 60 ± 10 |

| LynSH3eng | 100 ± 10 | 46 ± 8 |

| Fyn1Act | 70 ± 10 | 4.7 ± 0.8 |

| Fyn1SH2eng | 31 ± 9 | 8.5 ± 1.0 |

| Fyn1SH3eng | 45 ± 6 | 160 ± 30 |

| Fyn2Act | 50 ± 8 | 31 ± 7 |

| Fyn2SH2eng | 90 ± 30 | 40 ± 10 |

| Fyn2SH3eng | 40 ± 3 | 70 ± 20 |

Consistent with the introduced regulatory mutations strengthening autoinhibitory interactions, SFKSH3eng and SFKSH2eng constructs are less active than their SFKAct counterparts (Figure 2B). However, in contrast to SFKAct constructs, there is greater diversity in catalytic activity among autoinhibited constructs. For example, Fyn1SH3eng is notably more active than Fyn2SH3eng or LynSH3eng (Figure 2B, right panel). This Fyn1 mutant exhibits an activity more than 10-fold greater than that of Fyn1SH2eng [being only ∼3-fold less active than Fyn1Act (Figure 2C, right panel)]. However, Fyn2SH2eng is much more active than either Fyn1SH2eng or LynSH2eng (Figure 2B, middle panel). To confirm that Fyn1SH3eng’s relatively high catalytic activity compared to that of Fyn2SH3eng is not a result of differences in occupancy between the introduced high-affinity SH2-CD linker and the Fyn SH3 domain, a series of pull-down experiments to determine SH3 domain accessibility were performed (Figure 3A). Fyn constructs of interest were incubated with resin displaying an SH3-binding peptide. After being washed, the bound kinase was eluted and quantified. The amount of SFK retained on the beads is a reflection of the relative accessibility of their SH3 domains to engage in intermolecular binding interactions. Comparing the relative amounts of retained Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn2SH3eng provides a measure of how tightly each construct’s high-affinity linker engages the Fyn SH3 domain. Both Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn2SH3eng possess relatively inaccessible SH3 domains, presumably because of linker-SH3 domain engagement, relative to Fyn1Y527F (Figure 3B). Pull-downs using resin loaded with 5- and 10-fold more SH3 ligand than in the previous experiment were performed to test if intramolecular engagement could be outcompeted by higher concentrations of the immobilized SH3 domain ligand. The amount of Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn2SH3eng captured (and unbound) by each resin loading is almost identical, demonstrating that both Fyn1 and Fyn2 SH3eng constructs have similarly engaged SH3 domains (Figure 3C,D). Thus, the ability of regulatory interactions to transmit autoinhibition to the ATP-binding site varies dramatically among Fyn1, Fyn2, and Lyn. The fact that Fyn1 and Fyn2 have identical SH3 and SH2 domains provides evidence that SH2-CD linker variability strongly contributes to the relative ability of an SH2 or SH3 domain to autoinhibit the kinase domain. The functional consequences of SH2-CD linker variability, modulating the degree of allosteric coupling between intramolecular regulatory domain engagement and the ATP-binding site, may point to a source of nonredundancy between SFK family members in cells.

Figure 3.

The Fyn1 and Fyn2 SH3eng constructs have similarly inaccessible SH3 domains. (A) Schematic of the SH3 pull-down assay. SFK constructs are exposed to beads displaying an SH3-binding peptide. After being washed, the retained kinase is eluted, subjected to SDS–PAGE, and quantified by Western blotting or Coomassie staining. (B) Pull-down comparing the percent SFK retained on SH3-binding resin. Fyn1Y527F possesses an SH3 domain that is relatively accessible compared to those of Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn2SH3eng, which are similarly inaccessible (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (C) SDS–PAGE quantification of unbound Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn2SH3eng after incubation with 1.5 mM (1×), 7.5 mM (5×), and 15 mM (10×) SH3-binding peptide resin (mean ± SEM; n = 3). (D) SDS–PAGE quantification of Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn2SH3eng eluted from resin after incubation with 1×, 5×, and 10× loading resin (mean ± standard deviation; n = 2).

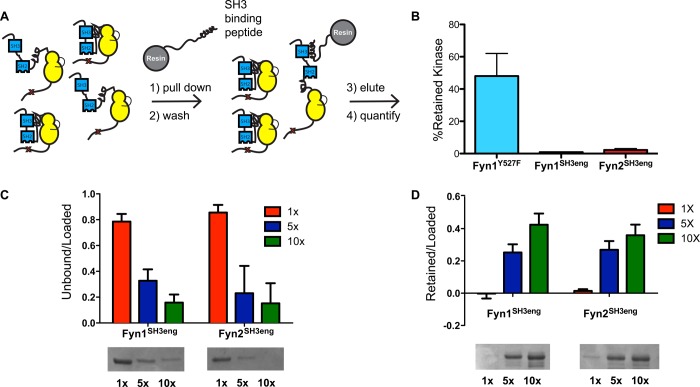

Conformation-Selective, ATP-Competitive Inhibitors Allow for Dissection of the Role of the αC Helix in Allosteric Coupling

The data in Figure 2 do not provide information about the overall conformation of the ATP-binding site for each SFK regulatory state mutant. To thoroughly explore how domain engagement influences SFK ATP-binding sites, a method for sensing ATP-binding site conformation is required. To provide more information about this parameter, the sensitivities of activated and autoinhibited Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2 constructs to conformation-selective, ATP-competitive inhibitors were determined. A representative panel of ATP-competitive ligands that are known or predicted to stabilize distinct SFK ATP-binding site conformations was employed (Figure 4A). By determining affinities of these ligands for various regulatory state SFK mutants, one can determine the influence of intramolecular interactions on ATP-binding site conformation. All inhibitors tested are pyrazolopyrimidine-based compounds with variable substituents at the C3 position. 1 (PP2) contains a 4-chlorophenyl group at the C3 position and has previously been found to have a minimal activation state preference for Src and Hck, making it a useful control for these studies.122–4 display small aryl moieties containing hydrogen bond donors and/or acceptors from their C3 positions and have been found to be selective for activated Src and Hck constructs over their autoinhibited forms.12,18 These inhibitors are predicted to stabilize an active ATP-binding site conformation by forming electrostatic interactions with catalytic residues that are aligned for catalysis. In contrast, 5–7 contain extended hydrophobic substituents at the C3 position, which have been shown to stabilize the ATP-binding sites of SFKs in an inactive conformation that involves rotation of the αC helix out of a catalytically competent alignment, the αC helix-out inactive conformation. Inhibitors of this class have been found to have a higher affinity for autoinhibited Src and Hck constructs than their activated counterparts. Unlike 2–4, 5–7 are not compatible with the αC helix being in an active conformation (see Figure 4B). Profiling active compatible (αC helix-in) and active incompatible (αC helix-out) ligands against Lyn and Fyn regulatory state mutants provides insight into how the allosteric relationship between αC helix conformation and regulatory domains for Fyn and Lyn compares to that for Src and Hck.

Figure 4.

Binding preferences of conformation-selective inhibitors reveal differences in allosteric coupling among Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2. (A) Conformation-selective inhibitor panel. 2–4 favor the ATP-binding site of active (αC helix-in) SFKs, while 5–7 stabilize the αC helix-out, inactive ATP-binding site conformation. These ligands allow systematic analysis of the ATP-binding site conformation in response to domain engagement. (B) Ligands that stabilize active and αC helix-out conformations make different contacts with the ATP-binding sites of SFKs. The left panel shows Src bound to 2 with the ATP-binding site in an active conformation (PDB entry 3EN4). An electrostatic interaction between the inhibitor and E310 in the αC helix is shown. The right panel shows Src bound to 6 with the ATP-binding site in the αC helix-out inactive conformation (PDB entry 4DGG). Helix αC is rotated out of the active site, disrupting the interaction between K295 and E310. (C) Quantitative comparison of the fold differences in Ki values between activated SFKs (SFKAct) and their respective autoinhibited constructs (SFKSH2eng) for 1–4. Previously reported data for Src and Hck are plotted for reference.18 (D) Quantitative comparison of the fold differences in Ki values between activated SFKs (SFKAct) and their respective autoinhibited constructs (SFKSH2eng) for 6 and 7. Previously reported data for Src and Hck are plotted for reference. The left-most column, marked with a dagger symbol, shows that the absolute fold difference in Ki value could not be determined because inhibitor affinity is lower than the enzyme concentration used in the assay. Ligand 5, which is marked with an asterisk in panel A, is too potent for Ki determination. All values are the average of assays performed in triplicate; the SEM for each value is less than 20% of the average Ki value. Ki values are listed in Figure S3 of the Supporting Information.

Comparing affinities of active and αC helix-out stabilizing ligands for autoinhibited (SFKSH2eng) and activated (SFKAct) constructs allows investigation of how intramolecular regulatory domain engagement influences ATP-binding site conformation for a particular SFK. More specifically, the fold difference in Ki values for a given ligand between SFKAct and SFKSH2eng constructs provides information about the equilibrium between active (αC helix-in) and inactive (αC helix-out) conformations of an SFK’s ATP-binding site. SFKAct and SFKSH2eng constructs were selected because they represent the extremes of regulatory domain allosteric control over catalytic activity for both Fyn and Lyn, fully active and fully autoinhibited. Ki values for the entire panel of active stabilizing and αC helix-out preferring ligands were obtained for LynAct, Fyn1Act, Fyn2Act, LynSH2eng, Fyn1SH2eng, and Fyn2SH2eng using standard activity assays. The results of the assays performed are summarized in panels C and D of Figure 4, which plots the ratio of inhibitor affinity for the SFKAct construct over the inhibitor affinity for the SFKSH2eng construct, or vice versa. Ki values for these ligands against Src and Hck were also included as a reference.18 As expected, compound 1 displays a minimal activation state binding preference for Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2 (Figure 4C). Consistent with previous observations for Src and Hck, αC helix-out ligands 6 and 7 bind with a higher affinity to SFKSH2eng constructs than to activated SFKs (Figure 4D). Active ATP-binding site-stabilizing ligands 2–4 show the opposite preference (Figure 4C). Despite the overall similar trend in conformation-selective inhibitor selectivity for Hck, Src, Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2 regulatory state mutants, there are some significant differences in the magnitudes of these preferences among the SFKs. Most notably, Fyn1 possesses the most distinct conformation-selective inhibitor profile. Fyn1SH2eng shows the lowest selectivity for ligands 6 and 7 relative to its activated construct (Fyn1Act). Furthermore, 2–4 demonstrate a much larger fold difference in affinity for Fyn1Act versus Fyn1SH2eng, relative to the other SFKs. As both ligand classes (2–4 and 6 and 7) most likely make favorable contacts with different conformations of the αC helix, this structural element appears to be unique in Fyn1. The difference in fold preference is especially striking compared to that of Fyn2, which possesses the exact same SH3 and SH2 domains as Fyn1 and 97% identical CDs (only eight residues are different in the N-terminal lobe). The fact that Fyn2 behaves more like Hck, Src, and Lyn than Fyn1 in the presence of conformation-selective inhibitors suggests that the SH2-CD linker, which is unique for Fyn1, plays a major role in the conformation of the αC helix.

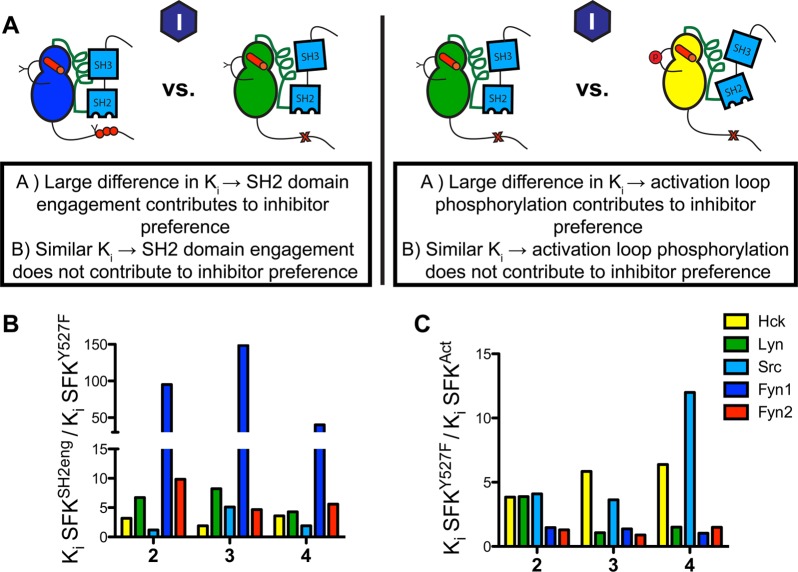

Regulatory Domain Engagement, but Not Activation Loop Phosphorylation, Is the Major Determinant of SFK Sensitivity to Ligands 2–4

SFK catalytic activity is predominantly governed by two factors: activation loop phosphorylation (activating) and regulatory domain engagement (autoinhibiting). We were interested in seeing if we could use our panel of inhibitors and regulatory state mutants to determine which factor, activation loop phosphorylation or regulatory domain engagement, governs the changes in ATP-binding site conformation driving the extreme difference in affinity observed between Fyn1Act and Fyn1SH2eng for ligands 2–4. To do this, Ki values for ligands 2–4 were determined for each SFKY527F construct and compared to those for SFKAct, to probe activation loop phosphorylation, or SFKSH2eng, to probe SH2 domain engagement (Figure 5 and Figure S4 of the Supporting Information). The Y527F construct was chosen as a basis for comparison because it is neither activation loop-phosphorylated nor engineered to favor regulatory domain engagement. This analysis shows that SH2 domain engagement determines the affinity of ligands 2–4 for the ATP-binding sites of all SFKs tested, because a larger difference in affinity is observed between SFKSH2eng and SFKY527F than between SFKY527F and SFKAct. This is particularly true for Fyn1, providing evidence that the ATP-binding site conformation equilibrium for Fyn1Y527F favors the active, αC helix-in conformation to a greater extent than all other SFKY527F constructs tested, even in the absence of activation loop phosphorylation.

Figure 5.

Effects of activation loop phosphorylation and regulatory domain engagement on the ATP-binding sites of SFKs. (A) Schematic of the analysis that was performed. Ki values for SFKSH2eng and SFKAct are compared to those for SFKY527F to determine whether activation loop phosphorylation or SH2 domain engagement influences the affinity of 2–4. (B) Quantitative comparison of the differences in Ki values between SFKSH2eng and SFKY527F for ligands 2–4. All values are the average of assays performed in triplicate; the SEM for each value is less than 20% of the average Ki value. (C) Quantitative comparison of the fold difference in Ki values for SFKY527F vs SFKAct. All values are the average of assays performed in triplicate; the SEM for each value is less than 20% of the average Ki value. Ki values are listed in Figure S4 of the Supporting Information.

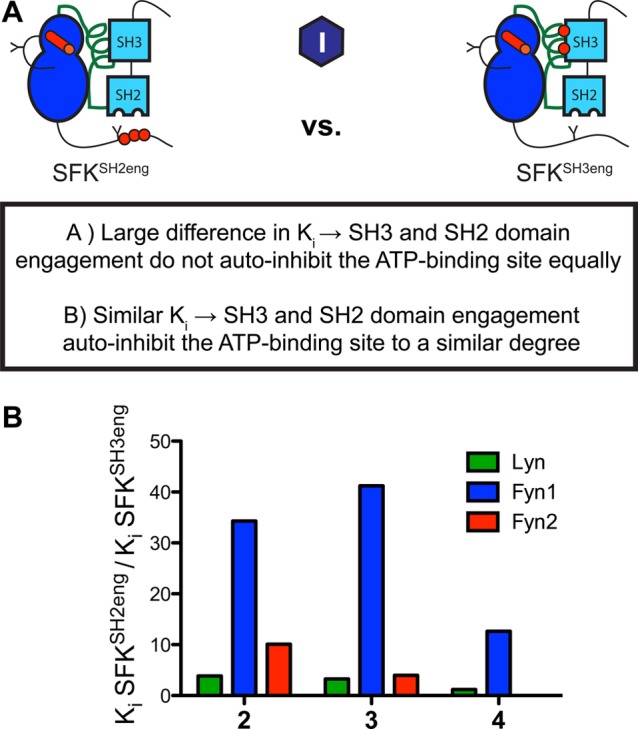

ATP-Binding Site Profiling of SFKSH3eng and SFKSH2eng Regulatory State Mutants Confirms Decoupling of SH3 Domain Engagement from αC Helix Conformation in Fyn1

Because of the disparate activities of the autoinhibited SH2eng and SH3eng Fyn1 constructs (Figure 2B), we investigated whether this difference in activity is manifested in the observed affinities of inhibitors 2–4 for Fyn1SH3eng versus Fyn1SH2eng using a similar strategy as described in Figure 5 (Figure 6A). SH3 domain binding is predicted to align a network of residues in the SH2-CD linker that stabilizes the αC helix in an inactive conformation (Figure 1C). Therefore, it is odd that enhancing the affinity of Fyn1’s SH2-CD linker for its SH3 domain would not autoinhibit the enzyme to an extent similar to that observed for Lyn and Fyn2 (Figures 2 and 3). On the basis of the relatively large differences in catalytic activities between the Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn1SH2eng constructs, we predicted that Fyn1SH3eng would possess a more active ATP-binding site conformation. To test this, the Ki values of ligands that prefer an active conformation (2–4) were determined for Fyn1SH3eng and Fyn1SH2eng (Figure S5 of the Supporting Information). As predicted, ligands that prefer an active ATP-binding site conformation possess a higher affinity for Fyn1SH3eng than for Fyn1SH2eng (Figure 6B). In contrast, the SH3eng and SH2eng constructs of Lyn and Fyn2 possess similar affinities (∼1–10 SH3eng/SH2eng ratios) for these ligands. The fact that ligands 2–4 do not show an equally strong preference for Fyn2SH3eng over Fyn2SH2eng is strong evidence that the decoupling of Fyn1’s SH3 domain from the αC helix is dependent on the SH2-CD linker. Unlike most SFKs, in which SH3 domain engagement directly results in autoinhibition, Fyn1’s SH2-CD linker requires SH2 domain engagement to allosterically couple SH3 domain binding to the αC helix.

Figure 6.

Intramolecular engagement of Fyn1’s SH3 domain minimally influences the conformation of its αC helix. (A) Schematic of the analysis that was performed. Ki values for SFKSH2eng and SFKSH3eng were measured and compared for each SFK. Differences in affinity between SFKSH2eng and SFKSH3eng indicate differential effects of SH3 and SH2 binding on the ATP-binding site. (B) Quantitative comparison of the fold difference in Ki values for SFKSH2eng and SFKSH3eng, illustrating the effects of SH2 domain or SH3 domain binding on ATP-binding site conformation. Compounds 2–4 greatly prefer Fyn1SH3eng over Fyn1SH2eng, showing that despite enhanced SH3 domain engagement Fyn1 maintains an active, αC helix-in binding site. Ki values are listed in Figure S5 of the Supporting Information.

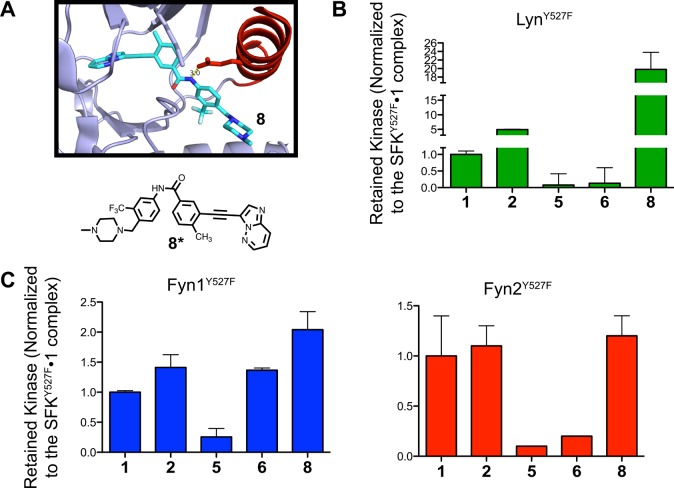

αC Helix Conformation Is Less Coupled to SH3 Domain Intramolecular Engagement in Fyn1 Than in Fyn2, Lyn, Src, and Hck

Given the surprising differences that were observed in how regulatory domain engagement affects ATP-binding site conformation in Fyn1 and Fyn2, we next investigated how αC helix conformation affects intramolecular regulatory domain engagement using our panel of conformation-selective ligands. SH3 domain accessibility was measured using the pull-down assay described in the legend of Figure 3. Each SFK of interest was incubated with a saturating amount of a conformation-selective inhibitor before being exposed to SH3-binding peptide resin. Comparing the relative amounts of retained Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2 when they are bound to active or αC helix-out stabilizing ligands provides a measure of how αC helix conformation influences SH3 domain accessibility within the context of each SFK. Ligand 8, which stabilizes an inactive activation loop conformation (DFG-out) but an active αC helix conformation (αC helix-in), was also tested to investigate the contribution of the activation loop to regulatory domain accessibility. Ligands that stabilize the DFG-out inactive conformation form a hydrogen bond with Glu310 in the αC helix—similar to αC helix-in, active ligands 2–4—and are thus predicted to prefer the ATP-binding sites of activated over autoinhibited SFK constructs (Figure 7A). Consistent with this hypothesis, stabilizing the DFG-out conformation of Src and Hck results in increased SH3 domain accessibility.18 SH3 pull-downs were performed with LynY527F, Fyn1Y527F, and Fyn2Y527F in the presence of a saturating concentration of 1, 2, 5, 6, or 8 (Figure 7B). For each of these experiments, ligand 1, which has a minimal preference for the SFK activation state, was used as a reference compound. Representative blots for the data in Figure 7B are shown in Figure S6 of the Supporting Information.

Figure 7.

Conformation-selective inhibitors differentially modulate the SH3 domain accessibilities of Lyn, Fyn1, and Fyn2. (A) Molecular structure of ligand 8 and a crystal structure of 8 bound to the ATP-binding site of Abl (PDB entry 3OXZ). 8 stabilizes the DFG-out inactive conformation and is predicted to stabilize helix αC in an active conformation by forming an electrostatic interaction with Glu310. (B) Quantification of the SH3 pull-down experiment performed with LynY527F in the presence of saturating 1, 2, 4, 5, or 8 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). All data are normalized to the SFKY527F·1 complex (1 does not show a strong preference for SFKAct over SFKSH2eng). (C) Quantification of the SH3 pull-down experiment performed with Fyn1Y527F and Fyn2Y527F in the presence of saturating 1, 2, 4, 5, or 8 (mean ± SEM; n = 3). All data are normalized to the SFKY527F·1 complex. Representative blots are shown in Figure S6 of the Supporting Information.

Consistent with their predicted effects and previous results observed for Hck, more LynY527F kinase was retained by the SH3 peptide ligand resin in the presence of 2 than in the presence of 1 (∼5-fold increase), while much less bound the resin in the presence of 5 and 6 [∼10-fold decrease (Figure 7B)]. Strikingly, an ∼20-fold increase in the amount of kinase retained was observed in the presence of compound 8. This agrees with recently reported results for Src and Hck and is consistent with the observation that DFG-out ligands stabilize the αC helix in an active conformation. The same pull-down experiment was used to probe Fyn1 SH3 domain accessibility. Interestingly, while the trends in SH3 domain accessibility are the same for each Fyn1Y527F inhibitor complex, the relative differences in SH3 domain accessibility are much smaller than those of the Fyn1Y527F·1 complex (Figure 7C). Compound 5 reduced SH3 domain accessibility several-fold; however, the reduction is not as dramatic as that observed for LynY527F, and compound 6 failed to change SH3 domain accessibility to any detectable extent. Similarly, 2 and 8 do not significantly increase Fyn1’s SH3 domain accessibility. Next, pull-down assays were repeated using Fyn2Y527F to probe whether Fyn1’s anomalous SH2-CD linker is responsible for decoupling the αC helix from SH3 domain accessibility. The fact that Fyn2 displays a greater reduction in SH3 domain accessibility when bound to either 5 or 6 (comparable to the reduced levels observed with Src) suggests that this is indeed the case. However, unlike Lyn and Hck, Fyn2Y527F does not show a dramatic increase in SH3 domain accessibility in the presence of inhibitors 2 and 8. Thus, while the SH3 domain of Fyn2 shows allosteric coupling to its ATP-binding site stronger than that of Fyn1, this SFK behaves more like Src than Hck or Lyn. This similarity in behavior correlates with differences in the SH2-CD linker (Figure 1B).

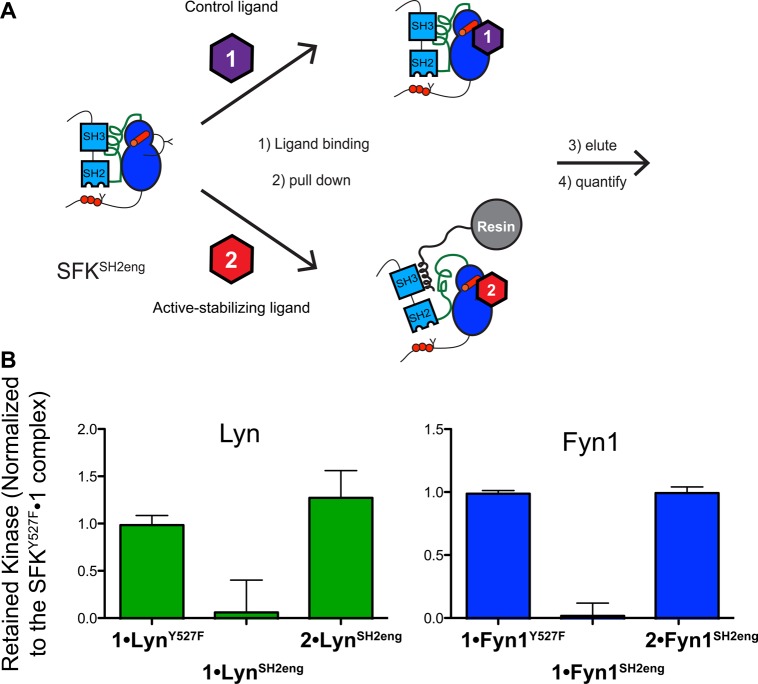

Inhibitor binding-mediated changes in SH3 domain accessibility were also explored using the SFKSH2eng construct (Figure 8A). Both LynSH2eng·1 and Fyn1SH2eng·1 complexes display a relatively inaccessible SH3 domain compared with that of the SFKY527F·1 complex, consistent with enhanced SH2–C-terminal tail intramolecular engagement promoting SH3 domain–SH2-CD linker interaction in both kinases. When they are bound to ligand 2, the SH3 domain accessibility of Fyn1SH2eng and LynSH2eng returns to a level on par with those of the Fyn1Y527F·1 and LynY527F·1 complexes, respectively (Figure 8B). These data show that adopting an active ATP-binding site conformation can overcome engineered regulatory domain engagement. It also indicates that although Fyn1 displays a reduced level of coupling between the SH3 domain and the ATP-binding site, enhancing the interaction between the SH2 domain and C-terminal tail is able to engage the SH3 domain and stabilize an αC helix-out inactive ATP-binding site. These effects can be reversed by stabilizing an αC helix-in, active ATP-binding site with a ligand.

Figure 8.

Stabilizing an active ATP-binding site conformation overcomes regulatory interactions in Lyn and Fyn1. (A) SH3 pull-downs were performed using SFKSH2eng constructs. SFKSH2eng constructs were incubated with control ligand 1 or active-preferring ligand 2 and the amounts of kinase retained on the resin compared. (B) Quantification of the SFKSH2eng SH3 pull-down experiment (mean ± SEM; n = 3). All data are normalized to the SFKY527F·1 complex.

The ability of ATP-binding site conformation to allosterically influence SH2 domain accessibility was also probed for Fyn1, Fyn2, and Lyn 3D constructs in pull-downs utilizing resin displaying an SH2-binding peptide (Figure S7 of the Supporting Information). The observed trends match the results from the SH3 pull-down experiments, but overall differences in SH2 regulatory domain accessibility are smaller. However, these results suggest that ATP-binding site conformation allosterically modulates SH2 domain accessibility to differing degrees between SFK family members.

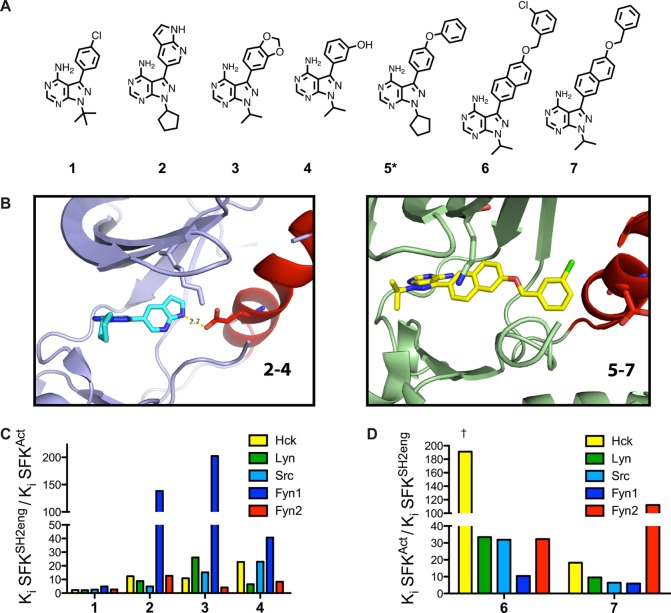

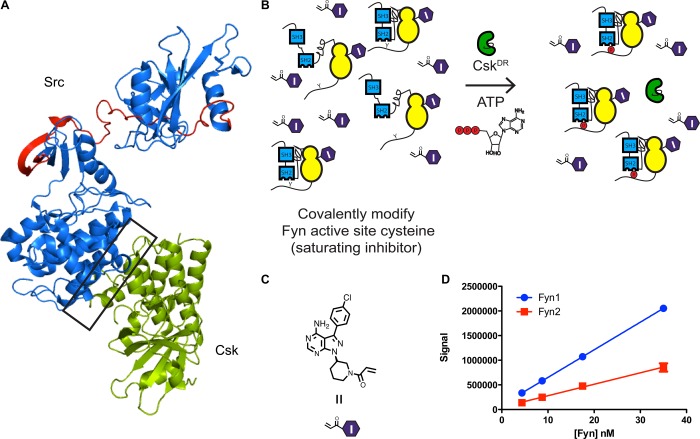

Comparison of Fyn1 and Fyn2 SH2 Domain Accessibility Demonstrates Biologically Relevant Consequences of SH2-CD Linker-Mediated Coupling among SFKs

Fyn1 and Fyn2’s SH2-CD linker variability results in surprising differences in the degree of allosteric coupling between the SH2 and SH3 domains and the ATP-binding site, but what are the biological consequences of more versus less coupling for a particular SFK? Csk is the primary kinase responsible for autoinhibition of SFKs in most cells.39,40 It phosphorylates Tyr527 on the C-terminal tail of all SFK family members, resulting in enhanced intramolecular engagement of the SH2 domain and autoinhibition. The biochemical studies described so far suggest that Fyn1’s reduced ATP-binding site–regulatory domain coupling results in greater overall regulatory domain accessibility regardless of ATP-binding site conformation compared to Fyn2. Thus, one would predict that Fyn1’s C-terminal tail would be more vulnerable to phosphorylation by Csk than Fyn2’s tail. Csk has been shown crystallographically to interact only with the C-terminus of Src.41 Fyn1 and Fyn2 possess identical C-termini; thus, comparing the rate of phosphorylation is directly probing how SH2-CD linker variation between the two isoforms affects post-translational modification (Figure 9A).

Figure 9.

SH2-CD linker affects availability of the C-terminal tail to post-translational modification by Csk. (A) Crystal structure of regulatory domain-disengaged Src (blue, PDB entry 1Y57) superimposed on a cocrystal structure of the SrcCD–Csk complex (green, PDB entry 3D7T). The interface between Csk and Src is boxed, while the variable region between Fyn1 and Fyn2 is colored red. Regions colored blue are identical between Fyn1 and Fyn2. (B) Scheme for measuring pTyr527 phosphorylation of inhibitor-bound Fyn1 and Fyn2 complexes by Csk. (C) Structure of a Michael acceptor analogue of ligand 1. (D) Graph displaying the results of the pTyr527 experiment. The radioactive phosphate signal is plotted vs Fyn concentration (mean ± SEM; n = 3).

To prevent the complication of competing C-terminal tail autophosphorylation obscuring the activity of Csk, inhibitor-bound complexes of Fyn1 and Fyn2 were used. Because of the high degree of sequence homology, the ATP-competitive ligands used in this study inhibit Csk in addition to SFKs, making it necessary to devise a scheme in which Fyn is completely inhibitor-bound but pTyr527 by Csk is uninhibited. To this end, Ser350 and Ser347 in the active sites of Fyn1 and Fyn2, respectively, were mutated to Cys, and a Michael acceptor analogue of 1 was used to covalently modify the Fyn active sites (Figure 9C). The pharmacophore of ligand 1 was selected because of its lack of activation state preference. As expected, the electrophile-modified version of 1 is a much more potent inhibitor of Fyn1 and Fyn2 active site Cys constructs than their wild-type counterparts (Figure S8 of the Supporting Information). Furthermore, it is possible to inhibit >98% of Fyn1S350C and Fyn2S347C without inhibiting a drug resistant Csk construct (CskDR) (Figure S8 of the Supporting Information). A Csk substrate peptide previously reported was used to verify the catalytic activity of CskDR.42

Varying concentrations of inhibitor-bound Fyn1S350C and Fyn2S347C were incubated with CskDR and [γ-32P]ATP, and the amount of pTyr527 was monitored over time (Figure 9B). Plotting the radioactive signal versus Fyn concentration reveals that Fyn1S350C is a better substrate for Csk than Fyn2S347C (Figure 9D). Activity assays in Figure 2 revealed that Fyn1 is more autoinhibited than Fyn2 when intramolecular engagement of the SH2 domain is enhanced. Therefore, these results predict that Fyn1 is more autoinhibited in vivo despite possessing an ATP-binding site that favors an active conformation. This conclusion is supported by cellular experiments: in HEK293 cells, Fyn1 displays more pTyr527 and less pTyr416 than Fyn2. As a result, the SH3 domain of Fyn1 is less available for intermolecular interactions than the SH3 domain of Fyn2.43

Discussion

In this study, we have investigated allosteric regulatory networks in SFKs. Beyond providing potential insight into SFK function, our results highlight how multidomain enzymes are able to fine-tune the transmission of binding events over large distances. All SFKs possess very similar regulatory domains, but via variation of a flexible structural element that couples regulatory domain interactions to their catalytic domains, diverse regulatory behavior can be achieved. Specifically, SH2-CD linker heterogeneity among SFKs influences the bidirectional coupling between their αC helices and regulatory domains. Using a panel of ATP-competitive inhibitors that stabilize the αC helix in two distinct conformations, we have probed (a) the conformation of the αC helix when intramolecular engagement of the SH2 and SH3 domains is enhanced or weakened and (b) how αC helix conformation affects SH2 and SH3 domain availability for intermolecular interactions for Fyn and Lyn. Given the high degree of sequence homology of SFK SH2, SH3, and CDs, we like many others in the field focused on the relatively nonhomologous SH2-CD linker as a source of nonredundant biological functions between SFKs. On the basis of previous work with Src and Hck, we further hypothesized that the SFK SH2-CD linkers uniquely govern the magnitude of allosteric coupling between the regulatory domains and the ATP-binding site, thus influencing the availability of the regulatory domains for intermolecular interactions. This comprehensive biochemical study is an important first step toward understanding how homologous protein kinases play nonredundant cellular roles.

Analysis of Fyn1 and Fyn2 serves as a direct probe into the influence of the SH2-CD linker on coupling between the SH3 and SH2 domains and the ATP-binding site. Fyn1’s longer dissimilar linker, characterized by a three-residue insertion, is primarily responsible for the reduced level of allosteric coupling between the αC helix and the SH3 domain compared to that observed for Fyn2 and all other SFKs investigated. Intriguingly, engagement of Fyn1’s SH2 domain autoinhibits the kinase to an extent greater than that observed for Fyn2 as demonstrated by decreased catalytic activity and diminished affinity for inhibitors that stabilize an active ATP-binding site. Rigorous analysis of the ATP-binding sites of Fyn1, Fyn2, Lyn, Src, and Hck with conformation-selective inhibitors suggests that, in the absence of post-translational modification and SH2 domain engagement, the ATP-binding site of Fyn1 favors an active conformation. In contrast, Fyn2 and other SFKs exhibit an ATP-binding site conformation somewhere between active and autoinhibited.

It has been proposed that allosteric regulation in SFKs follows a “snap-lock” mechanism, which postulates that SH3 and SH2 domains are coupled by the short linker segment connecting the two domains. The SH3–SH2 domain linker has been shown to be important for CD regulation by mutagenesis and molecular dynamics simulations.44 Tightly coupled SH3 and SH2 domains produce a kinase in which engagement of either the SH2 or SH3 domain recruits the other domain, while less coupled SH3 and SH2 domains result in a decreased level of synchronization between domains. NMR studies have shown that the SH3-SH2 domains of Fyn, identical between isoforms 1 and 2, are tightly coupled compared to the SFK Lck, which has a flexible SH3–SH2 linker.45 However, despite having identical SH3–SH2 linkers, Fyn1 shows an anomalous mechanism of autoinhibition in which SH3 domain engagement does not induce SH2 domain engagement or complete autoinhibition of the CD, as is generally the case for Fyn2, as well as Src, Lyn, and Hck. However, Fyn1 SH2 domain engagement is extremely effective at autoinhibiting the CD through a mechanism that is not entirely clear. It is possible that SH2 domain engagement stabilizes the SH2-CD linker in a conformation that allows for allosteric control over the CD through SH3 binding. SH2-CD linker variability can thus influence coupling of SH3 and SH2 domain engagement beyond the contribution of the SH3-SH2 linker. This result illustrates the importance of studying multidomain SFKs as opposed to individual domains.

SH2-CD linker heterogeneity has important consequences for SFK regulation and function in cells. This is illustrated by investigation of Fyn1 and Fyn2 C-terminal tail availability for phosphorylation by Csk. All in vitro evidence suggests that Fyn1 would be more active in cells; it is characterized by more SH3 domain accessibility regardless of αC helix conformation and favors an active ATP-binding site conformation compared to Fyn2 and other SFKs. However, experiments in HEK293 cells report that Fyn1 is less activation loop phosphorylated and possesses an SH3 domain that is less available for intermolecular interactions compared to that of Fyn2.43 We have shown that, because of its more accessible SH2 domain, Fyn1 is a better substrate for Csk phosphorylation and thus is more autoinhibited in cells when Csk is active. This implies that, because of Fyn1’s strong autoinhibition by SH2 domain engagement caused by its unique SH2-CD linker, Fyn1’s cellular function is determined by the competing activities of Csk and phosphatases to a greater extent than that of Fyn2 and other SFKs. This finding draws attention to the surprising consequences of SH2-CD linker differences in the complex environment of the cell.

Beyond providing insight into allosteric regulation within the SFKs, these studies suggest how individual SFKs are able to play nonredundant roles in cellular processes despite high degrees of sequence homology. For example, in Mast cell and B cell signaling, Fyn and Lyn have been demonstrated to play opposing and/or nonredundant functions.46−50 The structural source of this nonredundancy is currently unknown, but our results indicate that it may be due to SH2-CD linker heterogeneity between the two kinases.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- SFK

Src-family kinase

- CD

catalytic domain

- DR

drug-resistant

- SH3

Src homology 3

- SH2

Src homology 2

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- PPII

polyproline type II

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- SPS

Src peptide substrate

- 3D

three-domain

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- PDB

Protein Data Bank.

Supporting Information Available

Phospho-specific blots demonstrating quantitative activation loop phosphorylation of SFKAct constructs (Figure S1), sequence context and design of SFKSH3eng high-affinity linkers (Figure S2), Ki values for histograms in Figures 4–6 (Figure S3–S5, respectively), representative Western blots for pull-down bar graphs in Figure 7 (Figure S6), SH2 pull-down results for SFK3D constructs (Figure S7), and percent inhibition of CskDR and Fyn active site Cys constructs described in Figure 9 (Figure S8). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health via Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32GM008268 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (A.C.R.) and Grants R01GM086858 (D.J.M.) and F32CA174346 (S.E.L.) and the Alfred P. Sloan and Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundations (D.J.M.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Thomas S. M.; Brugge J. S. (1997) Cellular functions regulated by Src-Family kinases. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13, 513–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engen J. R.; Wales T. E.; Hochrein J. M.; Meyn M. A.; Banu Ozkan S.; Bahar I.; Smithgall T. E. (2008) Structure and dynamic regulation of Src-family kinases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 3058–3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim L. C.; Song L.; Haura E. B. (2009) Src kinases as therapeutic targets for cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 6, 587–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicheri F.; Kuriyan J. (1997) Structures of Src-family tyrosine kinases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 777–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W.; Doshi A.; Lei M.; Eck M. J.; Harrison S. C. (1999) Crystal Structures of c-Src Reveal Features of Its Autoinhibitory Mechanism. Mol. Cell 3, 629–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moarefi I.; LaFevre-Bernt M.; Sicheri F.; Huse M.; Lee C. H.; Kuriyan J.; Miller W. T. (1997) Activation of the Src-family tyrosine kinase Hck by SH3 domain displacement. Nature 385, 650–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicheri F.; Moarefi I.; Kuriyan J. (1997) Crystal structure of the Src-Family tyrosine kinase Hck. Nature 385, 602–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggon T. J.; Eck M. J. (2004) Structure and regulation of Src-Family kinases. Oncogene 23, 7018–7927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S. S.; Miller W. T. (2007) Cooperative activation of Src-family kinases by SH3 and SH2 ligands. Cancer Lett. 257, 116–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trible R. P.; Emert-Sedlak L.; Smithgall T. E. (2006) HIV-1 Nef selectively activates Src-family kinases Hck, Lyn, and c-Src through direct SH3 domain interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 27029–27038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Superti-Furga G.; Gonfloni S.; Weijland A.; Kretzschmar J. (2000) Crosstalk between the catalytic and regulatory domains allows bidirectional regulation of Src. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurty R.; Brigham J. L.; Leonard S. E.; Ranjitkar P.; Larson E. T.; Dale E. J.; Merritt E. A.; Maly D. J. (2012) Active site profiling reveals coupling between domains in Src-family kinases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonfloni S.; Williams J. C.; Hattula K.; Weijland A.; Wierenga R. K.; Superti-Furga G. (1997) The role of the linker between the SH2 domain and catalytic domain in the regulation and function of Src. EMBO J. 16, 7261–7271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaFevre-Bernt M.; Sicheri F.; Pico A.; Porter M.; Kuriyan J.; Millwer W. T. (1998) Intramolecular regulatory interactions in the Src-family kinase Hck probed by mutagenesis of a conserved tryptophan residue. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32129–32134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Superti-Furga G.; Gonfloni S.; Frischknecht F.; Way M. (1999) Leucine 255 of Src couples intramolecular interactions to inhibition of catalysis. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse M.; Kuriyan J. (2002) The conformational plasticity of protein kinases. Cell 109, 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado J. J.; Betts L.; Moroco J. A.; Smithgall T. E.; Yeh J. I. (2010) Crystal structure of the Src-family kinase Hck SH3-SH2 linker regulatory region supports an SH3-dominant activation mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35455–35461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard S. E.; Register A. C.; Krishnamurty R.; Brighty G. J.; Maly D. J. (2014) Divergent modulation of Src-family kinase regulatory interactions with ATP-competitive inhibitors. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 1894–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. C.; Wierenga R. K.; Saraste M. (1998) Insights into Src kinase functions: Structural comparisons. Trends Biochem. Sci. 23, 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacAuley A.; Cooper J. A. (1988) The carboxy-terminal sequence of p56lck can regulate p60C-src. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim W. A. (1996) Reading between the lines: SH3 recognition of an intact protein. Structure 4, 657–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. T. (2003) Determinants of substrate recognition in nonreceptor tyrosine kinases. Acc. Chem. Res. 36, 393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hah J.; Sharma V.; Li H.; Lawrence D. S. (2006) Acquisition of “Group A”: Selective kinase inhibitor via a global targeting strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 5996–5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashishian A.; MacAuley A.; Cooper J. A. (1990) Properties of tripartite chimeras between Src and Lck. Oncogene 5, 1463–1470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erpel T.; Superti-Furga G.; Courtneige S. (1995) Mutational analysis of the Src SH3 domain: The same residues of the ligand binding surface are important for intra- and inter-molecular interactions. EMBO J. 14, 963–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh M. D. (1998) Fyn, a Src-family tyrosine kinase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 30, 1159–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeliger M. A.; Young M.; Henderson M. N.; Pellicena P.; King D. S.; Falick A. M.; Kuriyan J. (2005) High yield bacterial expression of active c-Abl and c-Src tyrosine kinases. Protein Sci. 14, 3135–3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai H.; Varmus H. E. (1990) SH2 mutants of c-Src that are host dependent for transformation are trans-dominant inhibitors of mouse cell transformation by activated c-Src. Genes Dev. 4, 2342–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osusky M.; Taylor S. J.; Shalloway D. (1995) Autophosphorylation of purified c-Src at its primary negative regulation site. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25729–25732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart J. E.; Oppermann H.; Czernilofsky A. P.; Purchio A. F.; Erikson R. L.; Bishop J. M. (1981) Characterization of sites for tyrosine phosphorylation in the transforming protein of Rous sarcoma virus (pp60v-src) and its normal cellular homologue (pp60c-src). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 6013–6017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Lin X.; Gu X.; Parang K.; Sun G. (2006) Conformational basis for SH2-Tyr(p)527 binding in Src inactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 23776–23784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M.; Schindler T.; Kuriyan J.; Miller W. T. (2000) Reciprocal regulation of Hck activity by phosphorylation of Tyr(527) and Tyr(416). Effect of introducing a high affinity intramolecular SH2 ligand. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 2721–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner E. C.; Trible R. P.; Schiavone A. P.; Hockrein J. M.; Engen J. R. (2005) Activation of the Src-family kinase Hck without SH3-linker release. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40832–40837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen J. T.; Porter M.; Amoui M.; Miller W. T.; Zuckermann R. N.; Lim W. A. (2000) Improving SH3 domain ligand selectivity using a non-natural scaffold. Chem. Biol. 7, 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgarno D. C.; Botfiled M. C.; Rickles R. J. (1997) SH3 domains and drug design: Ligands, structure, and biological function. Pept. Sci. 43, 383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douangamath A.; Filipp F. V.; Klein A. T. J.; Barnett P.; Zou P.; Voorn-Brouwer T.; Vega M. C.; Mayans O. M.; Sattler M.; Distel B.; Wilmanns M. (2002) Topography for independent binding of α-helical and PPII-helical ligands to a peroxisomal SH3 domain. Mol. Cell 10, 1007–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay B. K.; Williamson M. P.; Sudol M. (2000) The importance of being proline: The interaction of proline-rich motifs in signaling proteins with their cognate domains. FASEB J. 14, 231–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B. J. (2001) SH3 domains: Complexity in moderation. J. Cell Sci. 114, 1253–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada M.; Nada S.; Yananashi Y.; Yamamoto T.; Nakagawa H. (1991) Csk: A protein-tyrosine kinase involved in regulation of Src-family kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 24249–24252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Superti-Furga G.; Fumagalli S.; Koegl M.; Courtneidge G.; Draetta G. (1993) Csk inhibition of c-Src activity requires both the SH2 and SH3 domains of Src. EMBO J. 12, 2625–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson N. M.; Seeliger M. A.; Kuriyan J. (2008) Structural basis for the recognition of c-Src by its inactivator Csk. Cell 134, 124–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondhi D.; Xu W.; Songyang Z.; Eck M. J.; Cole P. A. (1998) Peptide and protein phosphorylation by protein tyrosine kinase Csk: Insights into specificity and mechanism. Biochemistry 37, 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignatz C.; Paronetto M. P.; Opi S.; Cappellari M.; Audebert S.; Feuillet V.; Bismuth G.; Roche S.; Arold S. T.; Sette C.; Collette Y. (2009) Alternative splicing modulates autoinhibition and SH3 accessibility in the Src kinase Fyn. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 6438–6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young M. A.; Gonfloni S.; Superti-Furga G.; Roux B. (2001) Dynamic coupling between the SH2 and SH3 domains of c-Src and Hck underlies their inactivation by C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell 105, 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman G.; Schweimer K.; Kiessling A.; Hofinger E.; Bauer F.; Hoffman S.; Roch P.; Campbell I. D.; Werner J. M.; Sticht H. (2005) Binding, domain orientation, and dynamics of the Lck SH3-SH2 domain pair and comparison with other Src-family kinases. Biochemistry 44, 13043–13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios E. H.; Weiss A. (2004) Function of the Src-family kinases, Lck and Fyn, in T-cell development and activation. Oncogene 23, 7990–8000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okutaro T.; Asue Y.; Irofumi H.; Ishizumi N.; Hinichi S.; Izawa A.; Adashi T.; Amamoto Y.; Ensuke K.; Iyake M.; Hieko C.; Izoguchi M.; Hoji S.; Uji Y.; Ikuchi K.; Akatsu T. (1997) A critical role of Lyn and Fyn for B cell responses to CD38 ligation and interleukin 5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10307–10312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parravicini V.; Gadina M.; Kavarova M.; Odom S.; Gonzalex-Espinosa C.; Furumoto Y.; Saitoh S.; Samelson L. E.; O’Shea J. J.; Rivera J. (2002) Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat. Immunol. 3, 741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Huntington N. D.; Harder K. W.; Nandurkar H.; Hibbs M. L.; Tarlinton D. M. (2012) Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase activity in B cells is negatively regulated by Lyn tyrosine kinase. Immunol. Cell Biol. 90, 903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falanga Y. T.; Chaimowitz N. S.; Charles N.; Finkelman F. D.; Pullen N. A.; Barbour S.; Dholaria K.; Faber T.; Kolawole M.; Huang B.; Odom S.; Rivera J.; Carlyon J.; Conrad D. H.; Spiegel S.; Oskeritzian C. A.; Ryan J. J. (2012) Lyn but not Fyn kinase controls IgG-mediated systemic anaphylaxis. J. Immunol. 188, 4360–4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.