Abstract

The S1 → S2 transition of the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) of photosystem II does not involve the transfer of a proton to the lumen and occurs at cryogenic temperatures. Therefore, it is commonly thought to involve only Mn oxidation without any significant change in the structure of the OEC. Here, we analyze structural changes upon the S1 → S2 transition, as revealed by quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics methods and the isomorphous difference Fourier method applied to serial femtosecond X-ray diffraction data. We find that the main structural change in the OEC is in the position of the dangling Mn and its coordination environment.

Atmospheric oxygen is produced during the light reactions of photosynthesis in photosystem II (PSII), a complex of proteins and cofactors found in thylakoid membranes of green plant chloroplasts and internal membranes of cyanobacteria.1,2 Evolution of oxygen occurs because of the light-driven water oxidation reaction that is catalyzed by the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC), a cuboidal CaMn3 cluster with a dangling Mn held together by five putative μ-oxo bridges along with ligands that include four terminal water molecules and amino acid side chains of the D1 and CP43 protein subunits of PSII. The OEC often represents a model for biomimetic water oxidation catalysts because of its low overpotential (20 mV),3 its high turnover numbers (50 oxygen molecules per second),4 and the natural abundance of its constituent metal ions (Ca and Mn). A detailed investigation of the transformations of the OEC along the catalytic cycle is, therefore, a subject of great interest.

The catalytic cycle of PSII is initiated by absorption of photons by light-harvesting pigments and transfer of energy to the reaction center chlorophylls where charge separation and formation of a chlorophyll radical cation called P680+• occur. The OEC is oxidized by transfer of an electron to P680+• via the tyrosine residue (YZ). With each charge separation, the OEC stores an oxidation equivalent and advances through the storage states Si (i = 0–4) according to the so-called Kok cycle.5,6 Transformation of the dark-stable S1 state into the S2 state is the first step in the cycle and the only one that does not include the transfer of a proton to the lumen. It is, thus, commonly thought that the S1 → S2 transition involves only oxidation of a Mn center without any significant change in the structure of the OEC or its ligation scheme.7

X-ray diffraction (XRD) experiments have determined the structure and ligation scheme of the OEC,8−11 although the large doses of X-rays necessary for data collection typically induce radiation damage and alter the oxidation states of the Mn ions in the CaMn4O5 cluster.12,13 X-ray absorption measurements require much smaller X-ray doses and, therefore, are less affected by radiation damage.14,15 Recently, a new approach to protein crystallography, based on ultrashort X-ray pulses of high intensity, has allowed the collection of PSII diffraction data before the onset of radiation damage, although currently at a low resolution of 5.9 Å. While the method has been applied to microcrystals of PSII in the S1 and S2 states, no significant changes in the structure of the OEC have been detected upon the S1 → S2 transition.7

The S-state transitions have also been extensively studied by a variety of other experimental techniques, including time-resolved mass spectrometry,16,17 electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy,18 and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy.19−21 In particular, FTIR has been instrumental in detecting changes induced by the S1 → S2 transition in the properties of the carboxylate ligands. For example, the downshift of the νsym(COO–) mode of the α-COO– group of D1-Ala344 was evidence of weakening of the C=O bond.22 In addition, the perturbation of a νsym(COO–) mode19 was attributed to either D1-Glu333 directly ligated to the OEC cluster or D1-Asp61. Both findings were consistent with an increase in the charge of the CaMn4O5 cluster, induced by its oxidation without deprotonation during the S1 → S2 transition, and the resulting perturbation of the surrounding hydrogen-bonding network.

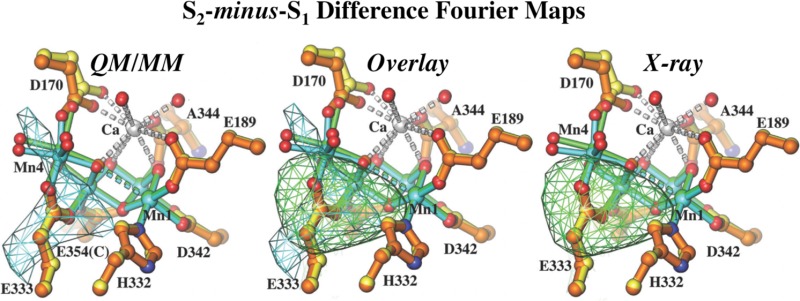

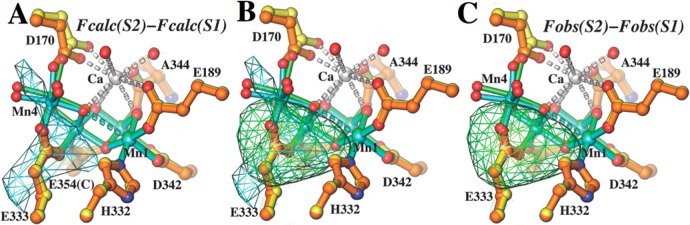

In this work, we re-examined the isomorphous difference Fourier maps using our newly improved phases and compare the experimental density difference maps to calculated density difference Fourier maps derived from quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) models. The analysis shows subtle but significant structural differences, including changes in the position of the dangling Mn (denoted here Mn4) and its coordination environment, induced by the S1 → S2 transition (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

QM/MM S1 and S2 models and difference Fourier maps. (A) Simulated S2-minus-S1 difference Fourier maps calculated using the QM/MM S1 and S2 models and phases derived from multicrystal noncrystallographic symmetry averaging (see the text for computational procedures and contour levels). The highest peak near the OEC results from the displacement of Mn4. (B) Comparison of the simulated S2-minus-S1 (from panel A) and X-ray-observed S2-minus-S1 (from panel C) difference Fourier maps with color codes according to panels A and C. (C) Observed S2-minus-S1 difference Fourier maps calculated from ref (7).

The QM/MM model of the S2 state was prepared by oxidation of the previously reported S1 QM/MM model in the Mn4[III,IV,IV,III] state.23,24 We consider the spin isomer of the S2 state that is formed under native conditions,25 corresponding to a doublet state (s = 1/2) that gives rise to the g = 2 multiline EPR signal. The oxidation-state pattern, Mn4[III,IV,IV,IV], is consistent with previous theoretical findings.26

Figure 1A shows the superposition of the QM/MM models for the S1 (yellow) and S2 (orange) states, with subtle structural rearrangements induced by the III → IV oxidation of Mn4. These include displacement of Mn4 from the membrane and symmetrization of the Mn4 coordination environment because of the loss of Jahn–Teller distortions. In addition, Figure 1A shows the S2-minus-S1 density difference (green mesh) calculated at 5.9 Å resolution by using the QM/MM S1 and S2 models and phases derived from multicrystal noncrystallographic symmetry averaging. We also compare the Fcalc(S2)-minus-Fcalc(S1) difference Fourier maps using phases initially derived from the partially refined S1 model and then from an averaging procedure (see the Supporting Information). Here, Fcalc(S2) and Fcalc(S1) denote the calculated structure factors from our hybrid S2 and S1 models, respectively.

We find that the underlying small structural displacements give rise to clear electron density differences, even at 5.9 Å resolution, because of the relatively high electronic density of Mn. In front of the displaced fragment that includes Mn4 and its ligands, we observe a positive density difference (green mesh) while the negative feature behind it is partially canceled out by other displacements in the same direction. Because the sizes of the density difference peaks are proportional to the magnitudes of the corresponding displacements, weighted by the absolute electronic density of the moving atoms, displacements of Mn centers are easier to detect than displacements of protein ligands. In fact, the peak height was ∼2.9σ when difference densities of the entire unit cell were used to calculate the standard deviation (see the Supporting Information). This implies that such small differences should be detectable given that the amplitude differences of 22.9% upon comparison of the observed X-ray data for the S1 and S2 states.7

Guided by an expectation of well-defined features in the S2-minus-S1 difference Fourier map generated from our QM/MM S1 and S2 models, we asked if similar features would be present in the observed S2-minus-S1 difference Fourier maps calculated from experimental X-ray data.7 Indeed, we find that the second highest peak in the entire unit cell was next the OEC of monomer A and overlapped with similar features in the simulated S2-minus-S1 difference Fourier maps (Figure 1). The peak was approximately 4.4–5.9σ; the height varied slightly, depending on the specific sets of phases used for the calculation (see the Supporting Information). In addition, there was a large negative peak near the putative electron extraction path (Figure S3C of the Supporting Information). There are two possible interpretations for the pair of difference density features. (i) The structure moiety between the positive and negative features is displaced as one rigid body, and (ii) the negative feature corresponds to the increased mobility of the aromatic residues nearby. It is noted that the two copies of PSII in the dimeric unit do not appear to behave the same during the S1 to S2 transition. Unfortunately, our QM/MM models cannot reliably address any structural changes away from the OEC.

In summary, we conclude that the structural changes of the OEC upon the S1 → S2 transition are subtle but can be addressed by an isomorphous difference Fourier method combined with QM/MM modeling. The most significant of those changes is a displacement of Mn4 from the protein membrane and a change in the coordination environment of Mn4 toward an ideal octahedron.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Steitz Center for Structural Biology, Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, Republic of Korea. We also acknowledge Dr. Rhitankar Pal, Dr. M. Zahid Ertem, Dr. Christian F. A. Negre, and Dr. Leslie Vogt for valuable discussions.

Supporting Information Available

Description of computational methods, QM/MM coordinates of the newly reported S2 state, and discussion and analysis of electron density maps. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, under Grants DESC0001423 to V.S.B. for computational work and DE-FG0205ER15646 to G.W.B. for experimental work. Crystallographic work was supported by National Institutes of Health Project Grant P01 GM022778.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- McEvoy J. P.; Brudvig G. W. (2006) Chem. Rev. 106, 4455–4483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson N.; Yocum C. F. (2006) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 521–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabolle M.; Dau H. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1708, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship R. E. (2008) Frontmatter. In Molecular Mechanisms of Photosynthesis, pp i–vii, Blackwell Science Ltd., Oxford, U.K. [Google Scholar]

- Kok B.; Forbush B.; McGloin M. (1970) Photochem. Photobiol. 11, 457–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot P.; Barbieri G.; Chabaud R. (1969) Photochem. Photobiol. 10, 309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Kern J.; Alonso-Mori R.; Tran R.; Hattne J.; Gildea R. J.; Echols N.; Glockner C.; Hellmich J.; Laksmono H.; Sierra R. G.; Lassalle-Kaiser B.; Koroidov S.; Lampe A.; Han G.; Gul S.; Difiore D.; Milathianaki D.; Fry A. R.; Miahnahri A.; Schafer D. W.; Messerschmidt M.; Seibert M. M.; Koglin J. E.; Sokaras D.; Weng T. C.; Sellberg J.; Latimer M. J.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; Zwart P. H.; White W. E.; Glatzel P.; Adams P. D.; Bogan M. J.; Williams G. J.; Boutet S.; Messinger J.; Zouni A.; Sauter N. K.; Yachandra V. K.; Bergmann U.; Yano J. (2013) Science 340, 491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zouni A.; Witt H.-T.; Kern J.; Fromme P.; Krauss N.; Saenger W.; Orth P. (2001) Nature 409, 739–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira K. N.; Iverson T. M.; Maghlaoui K.; Barber J.; Iwata S. (2004) Science 303, 1831–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guskov A.; Kern J.; Gabdulkhakov A.; Broser M.; Zouni A.; Saenger W. (2009) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umena Y.; Kawakami K.; Shen J. R.; Kamiya N. (2011) Nature 473, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano J.; Kern J.; Irrgang K. D.; Latimer M. J.; Bergmann U.; Glatzel P.; Pushkar Y.; Biesiadka J.; Loll B.; Sauer K.; Messinger J.; Zouni A.; Yachandra V. K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12047–12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabolle M.; Haumann M.; Muller C.; Liebisch P.; Dau H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4580–4588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachandra V. K.; Yano J. (2011) J. Photochem. Photobiol., B 104, 51–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau H.; Haumann M. (2008) Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- Messinger J.; Badger M.; Wydrzynski T. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 3209–3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier W.; Wydrzynski T. (2004) Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6, 4882–4889. [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. F.; Brudvig G. W. (1991) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1056, 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lizasa M.; Suzuki H.; Noguchi T. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 3074–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debus R. J. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1102, 269–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debus R. J. (2008) Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 244–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu H. A.; Hillier W.; Debus R. J. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 3152–3166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber S.; Rivalta I.; Umena Y.; Kawakami K.; Shen J.-R.; Kamiya N.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. (2011) Biochemistry 50, 6308–6311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal R.; Negre C. F. A.; Vogt L.; Pokhrel R.; Ertem M. Z.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. (2013) Biochemistry 52, 7703–7706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britt R. D.; Lorigan G. A.; Sauer K.; Klein M. P.; Zimmermann J. L. (1992) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1140, 95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A.; Ames W.; Cox N.; Lubitz W.; Neese F. (2012) Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 51, 9935–9940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.