Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of risk communication about bisphosphonate (BP)-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) on the number of reported cases to the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System and on the incidence proportion of ONJ in a hospital-based cohort study in Japan.

Method

We conducted a survey of the safety information on BP-related ONJ available from regulatory authorities, pharmaceutical manufacturers and academic associations. We also performed a trend analysis of a dataset from the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System and a sub-analysis, using previously constructed data from a retrospective cohort study.

Results

Risk communication from pharmaceutical manufacturers and academic associations began within 1 year after revisions were made to the package inserts, in October 2006. Twenty times more cases of ONJ have been reported to regulatory authority since 2007, compared with the period before 2007. In our cohort, the incidence proportion of ONJ during and after 2009 was four times greater than before 2009. During this period, BPs were frequently prescribed, whereas there was no increase in the use of alternative agents, such as selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Conclusion

ONJ was increasingly diagnosed after risk communication efforts, but the impact of the communications was not clear. Safety notifications were diligently disseminated after the package insert was revised. However, there was no surveillance for ONJ before the revision. © 2014 The Authors. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Keywords: risk communication, osteonecrosis of the jaw, oral bisphosphonates, pharmacoepidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), also called osteomyelitis of the jaw, is defined as the presence of exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that does not heal within 8 weeks.1–3 ONJ has received increasing attention since case reports about patients exposed to bisphosphonates (BPs) were published in 2003.4,5 In the United States of America (USA), regulatory authorities first indicated safety concerns about zoledronic acid and pamidronate with regard to osteonecrosis in 2003.6 In 2004, the manufacturer of zoledronic acid revised the package insert in the USA and issued a “Dear Health Professional” letter.7 Safety notifications regarding osteonecrosis were issued in other regions, such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand7 and Japan, in 2004 and 2005. Early case reports were followed by the publication of epidemiological studies in 2005 and 2006.8–10 Thereafter, position papers,11 guidelines12 and expert panel recommendations3,13 were published in 2006 and 2007. Some of these papers cautioned patients receiving oral BPs.3,11,13 The risk of ONJ for patients receiving oral BPs was considered much lower than the risk for patients receiving intravenous BPs.11,13 However, the incidence proportion of an adverse reaction was not fully studied until later, when the risk associated with oral BPs was proved to be smaller than that for intravenous BPs.14,15

Although dissemination of safety information to health care professionals or patients is the most common method for minimizing risk when a novel safety concern is discovered, the impact of risk communication has remained unknown and cannot be guaranteed to result in the intended effect.16,17 Few studies have addressed the long-term impact of risk communication on the incidence of adverse events and whether adverse events have been successfully reduced. Instead, the impact of risk communication is often assessed by measuring processes such as changes in drug use and by laboratory monitoring.17 Because ONJ is uncommon in the general population and its background incidence rate is low, we attributed an increase in disease reports to greater recognition of the disease among BP-exposed patients after risk communication, if the characteristics of the patients and the use of BPs did not change substantially. We expected that the risk communication initiative would decrease the incidence proportion of ONJ among BP-exposed patients, after a temporary increase.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of risk communication on oral BP-related ONJ in Japan; on the number of reported cases to the Japanese regulatory authority, the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System of the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA); and on the incidence proportion of ONJ in a hospital-based cohort study of 6923 osteoporosis patients at Kyoto University Hospital.

METHODS

We surveyed safety information about oral BP-related ONJ that was produced by the PMDA, pharmaceutical manufacturers and academic associations. We also conducted a trend analysis of a dataset from the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System of the PMDA and a sub-analysis, using the previously constructed data from a retrospective cohort study that was conducted at Kyoto University Hospital from February 2011 to July 2012.18 The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University (E1445).

Risk communication regarding oral BP-related ONJ

First, we surveyed the safety information from the PMDA by searching the PMDA Web site for the words “jaw” or “BPs” (accessed June to July 2012). We extracted articles on periodic safety information and letters and guidance publications, and we listed the relevant information after removing duplicate information. Second, we surveyed the types of risk communication materials concerning oral BP-related ONJ that were released by manufacturers marketing oral BPs in Japan and how and when they were disseminated. Two pharmaceutical companies collected letters and guidelines from the 10 manufacturers marketing oral BPs in Japan between July 2012 and January 2013. Finally, we collected information on the risk communications materials (type, timing of dissemination and method of dissemination) that were released by two academic associations (the Japanese Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons and the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research) between July and August 2012. One of the authors, a medical doctor, reviewed the collected communications materials and summarized the warnings and recommendations announced in the communications.

Reported cases of ONJ to the regulatory authority

A dataset containing the adverse drug reactions reported to the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System of the PMDA between April 2004 and December 2011 was downloaded, and the cases of ONJ suspected to be adverse reactions to osteoporosis medications (including oral BPs) were counted. We used the preferred terms in the Standardized Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Queries for “osteonecrosis,” with the exception of anatomically irrelevant terms, to retrieve the cases of ONJ. The list of drugs included in this study is shown in Appendix 1.

Cohort study

We conducted a cohort study of outpatients and inpatients who were diagnosed with osteoporosis, using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code (Appendix 2), and who received at least one prescription for an osteoporosis medication at Kyoto University Hospital during a study period (November 2000 to October 2010).18 The exclusion criteria were as follows: age younger than 20 years old; primary or metastatic tumors in the maxillofacial region; history of trauma or radiation therapy in the maxillofacial region; and intravenous treatment with BPs.

We extracted the clinical data from the electronic medical records (EMRs) using an EMR retrieval system.19 This system retrieves electronic data for outpatients and inpatients at Kyoto University Hospital, including demographic data, diagnoses and ICD-10 codes, medications and injections, laboratory tests and radiological and pathological studies. The median duration of oral BP administration, co-medications and comorbid conditions were also extracted using the EMR retrieval system.

The medications administered for osteoporosis between November 2000 and October 2010 in this cohort were collected by the retrieval system. The list of drugs included in the cohort study is shown in Appendix 3. The numbers of BP users, estrogen users and other osteoporosis drug(s) users in the cohort were calculated for each year, counting patients who were prescribed medications at least once during that year, regardless of the use of other osteoporosis medications.

To identify relevant ONJ cases, we reviewed the radiographic imaging and clinical records of the patients with a diagnosis of not only ONJ but also inflammatory conditions of the jaw that were possibly related to ONJ, as specified by the ICD-10 codes (Appendix 4). The diagnostic criteria were detailed in a previous report.18 Briefly, ONJ was diagnosed independently by two oral and maxillofacial surgeons in accordance with the proposed criteria, using the findings from panoramic X-rays, technetium bone scans, computed tomography, histological images or surgery. We grouped the cases of osteomyelitis of the jaw with ONJ because we considered it difficult to distinguish between these two diseases. The radiographic findings for jawbone infections in patients treated with BPs are similar to those for ONJ related to BPs,20–22 and the presence of osteonecrosis is a common histopathologic finding, both in ONJ and in osteomyelitis of the jaw related to BPs.23

The incidence proportion of confirmed ONJ was defined as the number of manually confirmed, newly developed ONJ cases in the cohort (e.g., BP group or non-BP group) in 2000–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008 and 2009–2010, divided by the size of the cohort for each 2- or 3-year period. The BP group included the patients who were prescribed BPs at least once during the period and/or in the past, regardless of the use of other osteoporosis medications; the non-BP group included the patients who were prescribed osteoporosis medication(s) other than BPs and those who had never been prescribed BPs.

The distinction between BP users in the drug use survey and the BP group in the incidence proportion survey was as follows: we classified a patient who received both BPs and estrogen in the same year as one BP user and one estrogen user over the same time period in the drug use survey. However, we classified the patient into the BP group rather than the non-BP group in the incidence proportion survey. This distinction was made because the impact of osteoporosis medications other than BPs on the incidence proportion of ONJ was considered to be negligible.

We evaluated the proportions of the cases recorded as inflammatory conditions of the jaw and alveolitis of the jaw (specified by ICD-10 codes K10.2, K10.3 and K10.0 [Appendix 4] in the EMR); the proportions were defined as the number of newly recorded cases of the inflammatory condition of the jaw in the EMRs of the cohort (e.g., BP users or non-BP users) during each 2- or 3-year period, divided by the size of the cohort during the period.

RESULTS

Risk communication regarding oral BP-related ONJ

The risk communication materials regarding oral BP-related ONJ, released by the PMDA, pharmaceutical manufacturers and academic associations, are listed in Table 1. The pharmaceutical manufacturers revised the package inserts in October 2006. The case reports or epidemiological studies regarding ONJ were published after the package insert was revised. Six separate but overlapping guidance announcements, in addition to the package insert, were issued. An academic association held educational meetings for health professionals and patients during their annual meeting in April 2008.

Risk communication about oral BP-related ONJ in Japan

| Date* | Organization | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Oct. 2006 | PMDA†, pharmaceutical manufacturers | Measure: revised package insert for alendronate and risedronate |

| “ONJ has been reported in patients receiving bisphosphonates. The majority of reported cases have been associated with dental procedures, such as tooth extraction, or with local infection. Physicians should fully disclose the adverse reactions to their patients and observe them closely.” | ||

| Jan. 2007 | pharmaceutical manufacturers | Notices to hospitals and “Dear Health Professional” letters to inform them about the content of the revised package insert |

| June 2007 | academic association | Publication of a case report33 |

| There was one case of osteoporosis diagnosed with oral BP-related ONJ; the other case, a case of multiple myeloma, was diagnosed with iv BP-related ONJ. | ||

| Sep. 2007 | PMDA, pharmaceutical manufacturers | Measure: revised package insert for etidronate |

| Oct. 2007 | academic association | Publication of an observational study34 |

| Questionnaires were sent to 239 institutions, and 30 patients with osteonecrosis were reported. Of them, 20 patients received iv BPs, eight received oral BPs and one received both. | ||

| Jan. 2008 | academic association | News article entitled “osteonecrosis of the jaws induced by anti-osteoporosis treatment” |

| “Patients on BP therapy requiring dental procedures should tell their dentists that they are being treated with BPs, and physicians should fully explain the adverse reactions to their patients when prescribing BPs.” | ||

| Jan. 2008 | academic association, pharmaceutical manufacturers | Announcement of a guidance publication, entitled “Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw” |

| A 20-page pamphlet, with the diagnostic criteria, clinical manifestations, risk factors and epidemiology of iv and oral BP-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and instructions for physicians, pharmacists, dentists and oral surgeons | ||

| Mar. 2008 | academic association | Announcement of guidance publication, entitled “management of patients on BP therapy” |

| A four-page pamphlet with the diagnostic criteria, management, risk factors, epidemiology of iv and oral BP-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and instructions for physicians, dentists and oral surgeons | ||

| Apr. 2008 | academic association | Public meeting for citizens: “The state of osteonecrosis of the jaw related to BPs” |

| Sep. 2008 | academic association | A pamphlet, entitled “Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw: clinical manifestations and guidelines for management, 2008” |

| Feb. 2009 | academic association | Training session for dentists, entitled “The state of osteonecrosis of the jaw related to BPs” |

| Feb. 2009 | academic association | News article, entitled “Bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws” |

| May 2009 | PMDA, academic association | Announcement of a guidance publication, entitled “Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws”35 |

| This official therapeutic manual for severe adverse reactions included the diagnostic criteria, clinical manifestations, risk factors and management methods for iv and oral BP-related osteonecrosis of the jaw for citizens and health care professionals | ||

| June 2009 | academic association | Public meeting for citizens, entitled “The state and the management of osteonecrosis of the jaws related to BPs” |

| July 2009 | academic association | Training meeting regarding BP-related osteonecrosis of the jaw for health care professionals |

| Nov. 2009 | academic association | Publication of an observational study36 |

| The follow-up survey showed that surgical treatment might be useful for BRONJ when performed at the appropriate time, and BRONJ was shown to be refractory because only nine of 17 cases were cured in these 2 years. | ||

| May 2010 | academic association, pharmaceutical manufacturers | Publication of a position paper37 |

| June 2010 | PMDA | Measure: revised package inserts for alendronate, risedronate and etidronate |

| “ONJ has been reported in patients receiving bisphosphonates, regardless of the route of administration. Treating physicians should advise their patients to undergo dental examinations and to finish any invasive dental procedures, such as tooth extraction, if necessary, prior to treatment with BPs. While on treatment with BPs, these patients should have regular dental consultations and avoid invasive dental procedures.” | ||

| Sep. 2010 | academic association | Publication of a book, entitled “The utility and osteonecrosis of the jaw of BPs” |

| Sep. 2010 | PMDA | Release of safety measures (“The progress of assessments and measures regarding BP-related osteonecrosis of the jaw”), including a survey of the number of cases of BP-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and an outline of the individual case reports reported to PMDA |

The date indicates the first dissemination of safety information.

PMDA: Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency.

Reported cases of ONJ to the regulatory authority

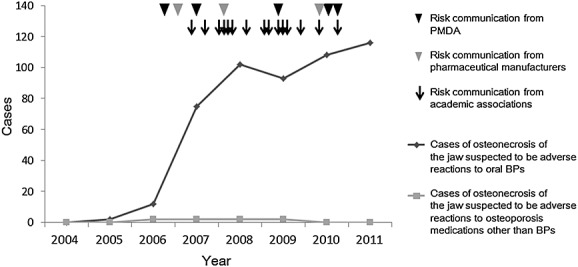

An increasing number of cases of ONJ that were suspected adverse reactions to oral BPs were reported to the PMDA after 2007, immediately after the safety information was disseminated (Figure 1). These cases included those with a past history of ONJ (that is, cases of ONJ that occurred earlier were reported as cases of ONJ after 2004 in the system). There were nearly 20 times more reported cases of ONJ during and after 2007, compared with the number of cases during and before 2006. Reported cases of ONJ that are suspected to have been adverse reactions to osteoporosis medications other than BPs have been rare. For reference, the estimated numbers of patients taking oral BPs in Japan were 2 082 928 in 2007 and 2 470 979 in 2008.24

Figure 1.

Trends in the number of ONJ cases per year reported to the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System of the PMDA and risk communication activities. Legend: The cases of ONJ that were suspected adverse reactions to oral bisphosphonates and those that were suspected adverse reactions to other agents for osteoporosis, reported to the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System of the PMDA, are shown as a dark gray line and a light gray line, respectively. Black arrowhead: risk communication from the PMDA; gray arrowhead: risk communication from pharmaceutical manufacturers; arrow: risk communication from academic associations

Cohort study

The cohort consisted of 6923 osteoporosis patients; 4129 were prescribed oral BPs (59.6%t;; mean age, 65.0), and 2794 patients received other osteoporosis drugs (40.3%t;; mean age, 65.5). The median durations of administration were 364.0 days for BPs and 439.5 days for other osteoporosis drugs. For the BP group and the other osteoporosis drugs group, the numbers of patients using concomitant steroids were 2934 (71.0%t;) and 1508 (53.9%t;), respectively; the numbers of patients treated with anti-cancer drugs were 551 (13.3%t;) and 256 (9.1%t;), respectively; and the numbers of patients with diabetes were 707 (17.1%t;) and 442 (15.8%t;), respectively.18

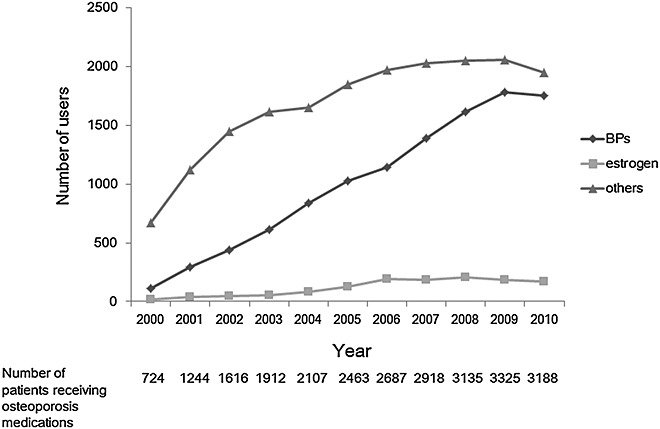

The number of BP users has been increasing steadily since 2000 (Figure 2). The number of estrogen users, including users of selective estrogen receptor modulators, has been low. The number of users of other osteoporosis medications, including active vitamin D3 or calcium, increased before 2006 and since then has remained approximately constant.

Figure 2.

The number of patients prescribed each agent for osteoporosis in the cohort. Legend: The numbers of patients prescribed bisphosphonates, estrogen and a selective estrogen receptor modulator, as well as other agents for osteoporosis, each year in a cohort of 6293 osteoporosis patients are illustrated with a dark gray line of diamonds, a gray line of triangles and a light gray line of squares, respectively. The year 2000 contains 2 months, and the year 2010 contains 10 months. The numbers of patients receiving osteoporosis medications in each year are shown below the graph

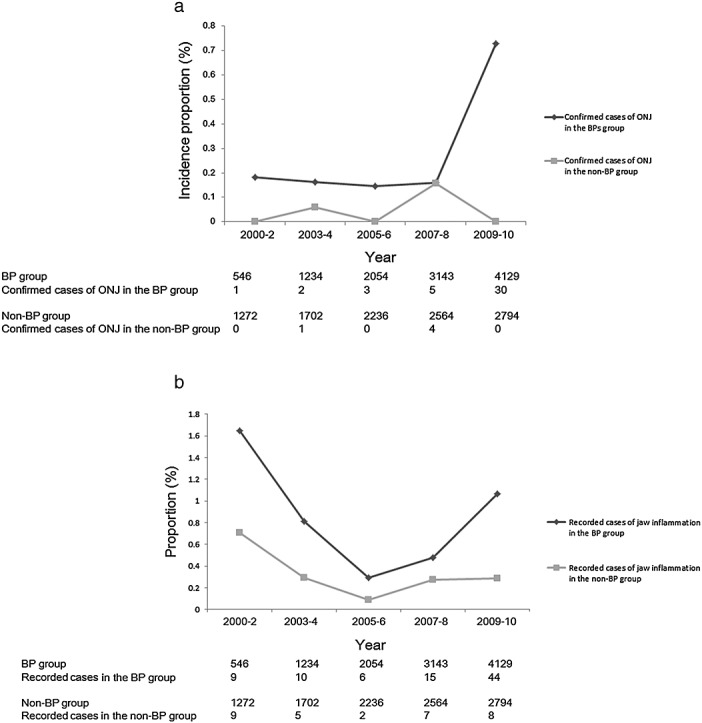

The EMRs of a total of 1987 patients with records of ONJ or inflammatory conditions of the jaw that were possibly related to ONJ were manually reviewed, and 46 patients were confirmed to have ONJ.18

The incidence proportion of confirmed ONJ in the BP group increased approximately four-fold in 2009 and 2010, compared with the pre-2009 level. The incidence proportion of confirmed ONJ in the non-BP group remained low (Figure 3a). Both of the incidence proportion of confirmed ONJ cases and that of inflammatory conditions of the jaw increased after 2009; however, the increase in inflammatory conditions of the jaw was not as high as that of confirmed cases (Figure 3b). This measure was therefore not a good surrogate for confirmed ONJ in this study.

Figure 3.

(a). The incidence proportion of confirmed cases of ONJ in the cohort. Legend: The incidence proportions of the confirmed ONJ cases in 100 BP-group patients in 2000–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008 and 2009–2010 are indicated by a dark gray line of diamonds. The incidence proportions of confirmed ONJ cases per 100 non-BP-group patients in each 2- to 3-year period are indicated by a light gray line of squares. The number of patients in the BP group, the number of confirmed ONJ cases in the BP group, the number of patients in the non-BP group and the number of confirmed ONJ cases in the non-BP group are shown below the graph. (b). The proportions of recorded ONJ cases in the cohort. Legend: The proportions of recorded cases of inflammatory conditions of the jaw in 100 BP-group patients in 2000–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008 and 2009–2010 are indicated by a dark gray line of diamonds. The proportions of recorded cases of inflammatory conditions of the jaw in 100 non-BP-group patients in each 2- to 3-year period are indicated by a light gray line of squares. The number of patients in the BP group, the number of recorded cases of inflammatory conditions of the jaw in the BP group, the number of patients in the non-BP group and the number of recorded cases of inflammatory conditions of the jaw in the non-BP group are shown below the graph

DISCUSSION

Risk communication efforts by pharmaceutical manufacturers and academic associations began within 1 year after the package insert was revised in October 2006, and ONJ was increasingly reported to the PMDA within 1 year. In our cohort, the incidence proportion of ONJ, diagnosed according to standardized criteria, increased in 2009 and in later years. During this period, BPs were frequently prescribed, and there were no increases in the use of alternative agents, such as selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Physicians' case reports regarding ONJ in 20034,5 in the USA led to revisions of package inserts in 2004 to 2005.7,25,26 In Japan, the pharmaceutical manufacturers revised the package inserts for intravenous BPs in 2005 and for oral BPs in 2006 and 2007, but the revision was delayed for 2 years after the revision in the USA. The physicians' case reports regarding ONJ were first published in 2007, 4 years after their publication in the USA; thus, the physicians' reports in Japan did not contribute to the increased suspicion of ONJ related to BPs or to the revision of the package insert. Academic associations were rather active in risk communication in the later dissemination phase. Physicians and academic associations have been able to detect new safety concerns for marketed drugs and to conduct epidemiological studies effectively, and we should reconsider academic associations, as well as the regulatory authority and pharmaceutical manufacturers, as resources for monitoring and minimization of the risks of medicines and for ensuring the accuracy of information.

We evaluated the impact of risk communications by analyzing the prescriptions of medications for osteoporosis and the incidence proportion of ONJ. The use of BPs increased steadily, but the prescriptions for BPs were not influenced by the risk communications in this study. BPs are among the most established drug types for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women,27 and the gradual increase in the use of BPs over the periods, before and after the dissemination of the safety information, was reasonable considering the risk–benefit balance. We could not determine whether the physicians prescribed BPs after considering the risk–benefit balance or simply did not receive the safety information. Many confounding factors can influence the prescription of BPs, such as the active participation of academic associations or the perceptions of physicians and patients toward adverse events. Physicians might hesitate to change prescribing habits because of known obstacles, such as the lack of time during outpatient care and the desire to maintain trust in the physician–patient relationship.28

The rapid increase in the cases of ONJ that were suspected adverse reactions to oral BPs reported to the regulatory authority after the risk communications efforts might indicate that the primary cause of the increase was awareness of the disease because the increase was quite sharp. The incidence proportion of ONJ in the BP group increased in our cohort, although the increase occurred 3 years after the risk communications began. There would have been few missed or misdiagnosed cases of ONJ in our cohort because the cases were diagnosed based on an extensive manual review of the EMRs, using well-established criteria. There might have been other causes for the increase in the incidence proportion of ONJ in our cohort in addition to risk communication; one possibility is the longer exposure to BPs8,29 in the cohort. Longer exposure and risk communication occurred simultaneously; therefore, we could not distinguish the impact of risk communication from that of longer exposure. There was a time difference between the increase in the number of cases of ONJ reported in the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System and the increase in the incidence proportion of ONJ in the cohort. The cases of ONJ reported to the Drug Adverse Reactions Reporting System include past cases of ONJ: cases that occurred before 2006 might be reported as cases of ONJ after 2006. Moreover, the diagnosis of ONJ is not standardized and might include other inflammatory conditions of the jaw. However, the number of ONJ patients in the cohort reflects the number of active ONJ patients diagnosed in the hospital. The difference between the recording and the diagnosis of ONJ most likely resulted in the time difference.

Previous reviews have found it difficult to estimate the average effect of risk communication on clinical practice16,17,30 because of heterogeneity in the study designs, analyses, outcome measurements, therapeutic areas and types of communication. ONJ can be reduced with preventive measures, including clinical oral examinations and good oral hygiene.31,32 Unfortunately, we did not observe a decrease in the incidence proportion of ONJ in our cohort during this study period, which would have been the clinical outcome. Additional appropriately designed research is warranted to understand the effects of past communications strategies and to estimate the impact of future communication.

The limitations of our study are described below. First, factors other than safety information collected in our study, such as pharmaceutical use, could have simultaneously influenced the incidence proportion of ONJ. Second, we did not consider the scale, the duration or the content of the risk communication; it is therefore not possible to evaluate the impact of each risk communication material quantitatively. Third, the data on drug use and on the incidence proportion of ONJ in Kyoto University Hospital were limited to a single institution in Japan; thus, the generalizability of the results cannot be assured. The much higher incidence of ONJ in our study compared to the published literature might be explained by the inclusion of numerous steroid users, older patients and inpatients. Moreover, the cohort study was subject to a referral bias toward the selection of more severe cases, given that our department is the lead institution for oral and maxillofacial surgery in Kyoto City, as discussed in our previous report.18 We could not account for BP exposure that occurred before consultation at Kyoto University Hospital, which might have affected the incidence proportion of ONJ. Finally, this study was retrospective, using a database derived from the EMRs, and the data were not as accurate and consistent as they would have been in a prospective study.

CONCLUSION

The use of oral BPs increased in osteoporosis patients, regardless of the safety notifications concerning ONJ related to BPs. ONJ was increasingly diagnosed after the dissemination of safety information about BP-related ONJ using repetitive and mixed communication methods; the impact of these communications materials was not clear. Our evaluation of the risk communication materials suggests that appropriate cooperation models involving the parties concerned with pharmacovigilance should be planned for the dissemination of safety information and for the delivery and evaluation of new safety concerns with marketed drugs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Eriko Sumi collected information on when, how and what type of risk communications regarding osteonecrosis of the jaw were released from pharmaceutical companies.

KEY POINTS

The use of oral bisphosphonates (BPs) in osteoporosis patients has increased regardless of safety concerns about osteonecrosis related to BPs. Osteonecrosis of the jaw was increasingly diagnosed after risk communication; however, the impact of the risk communication was not clear. Safety notifications were disseminated diligently after the package insert was revised. However, there was no surveillance for osteonecrosis of the jaw before the revision.

Acknowledgments

We thank Masahiro Urade of the Japanese Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, Toshiyuki Yoneda of the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Hiroyuki Nishimoto of the Takeda Pharmaceutical company and Minoru Shimodera of Merck & Co., Inc., for providing information about risk communication. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research of Japan (23790566).

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Supplementary

Appendix 1. List of drugs studied in cases of OMJ reported to the regulatory authority

Appendix 2. List of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code for osteoporosis studied in the cohort study

Appendix 3. List of drugs studied in the cohort study

Appendix 4. List of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code for inflammatory conditions of the jaw studied in the cohort study

REFERENCES

- 1.Campisi G, Fedele S, Colella G, et al. Canadian consensus practice guidelines for bisphosphonate associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:451–453. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080843. author reply 453. DOI: 10.3899/jrheum.080843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws--2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.01.009. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khosla S, Burr D, Cauley J, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1479–1491. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0707onj. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.0707onj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Migliorati CA. Bisphosphanates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4253–4254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Memorandum. 2003. http://www.fda.gov/OHRMS/DOCKETS/ac/05/briefing/2005-4095B2_03_03-FDA-TAB2.pdf (accessed 2013/3/5)

- 7.Edwards BJ, Gounder M, McKoy JM, et al. Pharmacovigilance and reporting oversight in US FDA fast-track process: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaw. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:1166–1172. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70305-X. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70305-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8580–8587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Anagnostopoulos A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma treated with bisphosphonates: evidence of increased risk after treatment with zoledronic acid. Haematologica. 2006;91:968–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Badros A, Weikel D, Salama A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in multiple myeloma patients: clinical features and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:945–952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.003. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruggiero S, Gralow J, Marx RE, et al. Practical guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2006;2:7–14. doi: 10.1200/jop.2006.2.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dental management of patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy: expert panel recommendations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1144–1150. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo JC, O'Ryan F, Yang J, et al. Oral health considerations in older women receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:916–922. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03371.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong JW, Nam W, Cha IH, et al. Oral bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: the first report in Asia. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:847–853. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1024-9. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dusetzina SB, Higashi AS, Dorsey ER, et al. Impact of FDA drug risk communications on health care utilization and health behaviors: a systematic review. Med Care. 2012;50:466–478. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a160. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piening S, Reber KC, Wieringa JE, et al. Impact of safety-related regulatory action on drug use in ambulatory care in the Netherlands. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:838–845. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.308. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamazaki T, Yamori M, Yamamoto K, et al. Risk of osteomyelitis of the jaw induced by oral bisphosphonates in patients taking medications for osteoporosis: a hospital-based cohort study in Japan. Bone. 2012;51:882–887. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.08.115. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.08.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto K, Sumi E, Yamazaki T, et al. A pragmatic method for electronic medical record-based observational studies: developing an electronic medical records retrieval system for clinical research. BMJ Open. 2012;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001622. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Junquera L, Gallego L. Nonexposed bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: another clinical variant? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1516–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.02.012. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mawardi H, Treister N, Richardson P, et al. Sinus tracts--an early sign of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.031. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchinson M, O'Ryan F, Chavez V, et al. Radiographic findings in bisphosphonate-treated patients with stage 0 disease in the absence of bone exposure. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2232–2240. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.003. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertoldo F, Santini D, Lo Cascio V. Bisphosphonates and osteomyelitis of the jaw: a pathogenic puzzle. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:711–721. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1000. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency Safety Information. 2010. September http://www1.mhlw.go.jp/kinkyu/iyaku_j/iyaku_j/anzenseijyouhou/272.pdf (accessed 1 February)

- 25.Lamb T. Did Merck Fail To Warn About Fosamax Side Effects? 2006. http://www.drug-injury.com/druginjurycom/2006/04/fosamax_drug_co.html (accessed 2013/6/30)

- 26.MERCK. Statement by Merck Regarding FOSAMAX® (alendronate sodium) and Rare Cases of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. 2010. http://www.mercknewsroom.com/news/statement-merck-regarding-fosamax-alendronate-sodium-and-rare-cases-osteonecrosis-jaw (accessed 2013/6/30)

- 27.Papaioannou A, Morin S, Cheung AM, et al. 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada: summary. CMAJ. 2010;182:1864–1873. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bahri P. Public pharmacovigilance communication: a process calling for evidence-based, objective-driven strategies. Drug Saf. 2010;33:1065–1079. doi: 10.2165/11539040-000000000-00000. doi: 10.2165/11539040-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marx RE, Cillo JE, Jr, Ulloa JJ. Oral bisphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis: risk factors, prediction of risk using serum CTX testing, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:2397–2410. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.08.003. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piening S, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, de Vries JT, et al. Impact of safety-related regulatory action on clinical practice: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2012;35:373–385. doi: 10.2165/11599100-000000000-00000. doi: 10.2165/11599100-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Reduction of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) after implementation of preventive measures in patients with multiple myeloma treated with zoledronic acid. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:117–120. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn554. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonacina R, Mariani U, Villa F, et al. Preventive strategies and clinical implications for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: a review of 282 patients. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka Noriaki KH, Takaoka K, Hashitani S, Sakurai K, Urade M. Two cases of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the mandible. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;53:392–396. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimahara Masashi AY, Imai Y, Mizuki H, Shimada J, Furusawa K, Morita S, Ueyama Y. A survey of bisphosphonate-related osteomyelitis/osteonecrosis of the jaws. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;53:594–602. [Google Scholar]

- 35.PMDA. 2009. Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws http://www.mhlw.go.jp/topics/2006/11/dl/tp1122-1l01.pdf (accessed 2013/6/3)

- 36.Urade Masahiro TN, Shimada J, Shibata T, Furusawa K, Kirita T, Yamamoto T, Ikebe T, Kitagawa Y, Kurashina K, Seto K, Fukuda J. A follow-up survey of 30 cases of bisphosphonate-related ostemyelitis/osteonecrosis of the jaws: present status after 2 years. Jpn J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;55:553–561. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoneda T, Hagino H, Sugimoto T, et al. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: position paper from the Allied Task Force Committee of Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral Research, Japan Osteoporosis Society, Japanese Society of Periodontology, Japanese Society for Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology, and Japanese Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. J Bone Miner Metab. 2010;28:365–383. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0162-7. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary

Appendix 1. List of drugs studied in cases of OMJ reported to the regulatory authority

Appendix 2. List of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code for osteoporosis studied in the cohort study

Appendix 3. List of drugs studied in the cohort study

Appendix 4. List of International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code for inflammatory conditions of the jaw studied in the cohort study