Abstract

Background

Obtaining data on attitudes toward buprenorphine and methadone of opioid-dependent individuals in the United States may help fashion approaches to increase treatment entry and improve patient outcomes.

Objectives

This secondary analysis study compared attitudes toward methadone and buprenorphine of opioid-dependent adults entering short-term buprenorphine treatment (BT) with opioid-dependent adults who are either entering methadone maintenance treatment or not entering treatment.

Methods

The 417 participants included 132 individuals entering short-term BT, 191 individuals entering methadone maintenance, and 94 individuals not seeking treatment. Participants were administered an Attitudes toward Methadone scale and its companion Attitudes toward Buprenorphine scale. Demographic characteristics for the three groups were compared using χ2 tests of independence and one-way analysis of variance. A repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance with planned contrasts was used to compare mean attitude scores among the groups.

Results

Participants entering BT had significantly more positive attitudes toward buprenorphine than toward methadone (p < .001) and more positive attitudes toward BT than methadone-treatment (MT) participants and out-of-treatment (OT) participants (p < .001). In addition, BT participants had less positive attitudes toward methadone than participants entering MT (p < .001).

Conclusions

Participants had a clear preference for a particular medication. Offering a choice of medications to OT individuals might enhance their likelihood of entering treatment. Treatment programs should offer a choice of medications when possible to new patients, and future comparative effectiveness research should incorporate patient preferences into clinical trials.

Scientific Significance

These data contribute to our understanding of why people seek or do not seek effective pharmacotherapy for opioid addiction.

Keywords: opioid addiction, attitudes, buprenorphine treatment, methadone treatment

INTRODUCTION

Buprenorphine’s availability for treating opioid dependence in the United States by prescription permits its use through outpatient (non-methadone) drug treatment programs and physicians’ offices. A recent evidence-based review of opioid agonist treatment found that buprenorphine at doses of 8 mg and above is more effective in the treatment of heroin dependence than placebo, but appears to be less effective than methadone at doses of 60–120 mg (1). Nevertheless, buprenorphine’s superior safety profile, its ability to be prescribed outside of opioid treatment programs (OTPs), and its effectiveness make it a highly valuable addition to the treatment options available to opioid-dependent individuals (2).

One potential advantage of buprenorphine over methadone is that the former may not be encumbered by the negative views that surrounded methadone since its introduction (3). Early studies of attitudes toward methadone indicated concerns – particularly among African Americans – that methadone could be injurious to health, more addictive than heroin, and used for social control (4). Research since the early 1970s has found that these negative attitudes have persisted (5,6). Our own research with out-of-treatment (OT) heroin users (7) and our study of attitudes toward methadone and buprenorphine among opioid-dependent individuals in and out of methadone treatment (MT) suggest little has changed with regard to attitudes toward methadone (3). In the latter study, both methadone and OT study participants rated buprenorphine more positively than they rated methadone, though this appeared to reflect neutrality toward buprenorphine in conjunction with negative feelings for methadone (3). Rieckmann et al. (8) reported similar neutral attitudes toward buprenorphine among patients in MT as well as patients in residential and outpatient treatment, and more positive attitudes toward methadone among adults in MT than adults in other treatment modalities.

The Institute of Medicine recommends that patient-centered care that accommodates patient preferences be used to improve the quality of medical care (9). There is growing evidence that patient preferences in mental health and substance abuse treatment can lead to better patient outcomes, including decreases in dropout (10). Though there are relatively few patient preference studies in substance abuse treatment, one such study that offered a choice of methadone or buprenorphine found that 28% of patients who chose buprenorphine (10% of the total sample) would not have accessed treatment if only methadone were available (11).

The public health importance of the expansion of buprenorphine treatment (BT) suggests the need for additional research to clarify patients’ attitudes toward buprenorphine and how those attitudes compare to attitudes toward methadone. Because many methadone programs do not offer buprenorphine and neither outpatient drug abuse clinics nor physician offices in the United States offer methadone, it is important to understand more about patient attitudes to improve efforts to match patients to treatment and to attract the many OT individuals to pharmacotherapy. Building on our earlier findings (3), this study compares the attitudes of opioid-dependent individuals entering short-term BT to attitudes of individuals who are entering MT and opioid-dependent individuals who are not entering nor seeking any drug treatment.

METHODS

Participants

All participants were opioid-dependent adults recruited in Baltimore for participation in one of two National Institute on Drug Abuse-funded parent studies, described in detail elsewhere (12,13). The first parent study examined entry and engagement in MT. Participants were two cohorts of opioid-dependent adults (one cohort entering MT and the other cohort neither entering nor seeking treatment). The second parent study examined the responses to counseling among patients enrolling in a short-term outpatient BT. Secondary analysis of data from the parent studies, which were approved by Friends Research Institute’s IRB, was conducted for the current investigation.

The study sample consisted of 417 opioid-dependent adults, including 132 individuals beginning a 30-day course of buprenorphine in a formerly drug-free outpatient clinic, 191 individuals entering MT, and 94 individuals recruited from the streets who were neither entering nor seeking drug treatment. Of the 417 participants, 3 participants, all from the BT group, had not heard of methadone (<1% of total sample; <1% of buprenorphine group). A total of 38 participants (9% of total sample) had not heard of buprenorphine, including 18 from the buprenorphine group (14%), 10 from the methadone group (5%), and 10 from the OT group (11%).

BT Sample

Participants entering 30-day BT as part of a community-based outpatient (non-methadone) program were recruited from May 2006 through April 2008 (13). Study eligibility required that participants were at least 18 years of age and had symptoms of opioid withdrawal as determined by physician evaluation at intake.

MT Sample

MT participants were recruited between April 2006 and October 2007 upon admission to one of six Baltimore area programs (12). Study eligibility required participants to be a minimum of 18 years of age and meet the criteria for methadone maintenance (at least one continuous year of opioid dependence).

OT Sample

Participants were recruited between April 2006 and November 2007 from 12 street locations in Baltimore city chosen through targeted-sampling methods described in detail elsewhere (12,14). These 12 locations were selected based on data obtained from the local government on drug-related problems and ethnographic data obtained from outreach workers and the police about the city’s drug scene. Research staff approached potential participants in the street to screen for eligibility. In addition to meeting the same study eligibility requirements as the MT sample, participants were required to neither have had nor sought any type of drug treatment in the prior 12 months.

Measures

Participants were administered two brief screening questionnaires (one for methadone and one for buprenorphine) at treatment entry that asked whether they had heard of the medication, what they had heard about it, and whether they had used it through prior treatment or street use. If the participants had heard of the medication, they were then administered the respective Attitudes toward Methadone or Attitudes toward Buprenorphine scale.

Items for the original Attitudes toward Methadone scale (4) were derived from an existing 10-item questionnaire (15) exploring drug use issues and from open-ended interviews conducted with methadone patients in treatment programs in Washington, DC. The current scale has 28 items that inquire about participants’ perceptions of methadone pertaining to health and safety, addictive qualities, effectiveness, and stigmatization. Examples of scale items are (i) methadone takes away the craving for heroin; (ii) methadone can rot your bones; and (iii) taking methadone is only replacing one addiction with another (4). Responses for each of the 28 items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” with 5 indicating the most positive rating.

The Attitudes toward Buprenorphine scale (3) was created by substituting the word “buprenorphine” for “methadone” in the methadone scale. Item responses were summed within each questionnaire to provide separate scores of attitudes toward methadone and buprenorphine. Previous research found internal consistency α values of .75 for the Attitudes toward Methadone scale and .76 for the Attitudes toward Buprenorphine scale (3).

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (16) was also administered to all participants at treatment entry. Participant demographics such as gender, age, race, education, marital status, and past 30-day employment were drawn from the ASI.

Statistical Analysis

The BT group was first compared with the MT group and the OT group on several participant characteristics using χ2 tests of independence for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables. A repeated-measures multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with the between-subjects factor of Group (BT vs. MT vs. OT) and the within-subjects factor of Scale (buprenorphine vs. methadone) was conducted to test the questions of interest. Two single-df planned comparisons within the MANOVA model were utilized, comparing (i) mean attitude scores toward methadone and buprenorphine for the BT group alone and (ii) mean attitude scores for the BT group with scores for each of the other two groups on each scale. Gender, race, age, education, marital status, and whether participants had any prior BT episodes were included as covariates in all analyses in order to control for possible differences among the three groups. Because only the MT group consisted of participants who had enrolled in one of six treatment programs, it was not possible to control for possible treatment program site differences in the analyses.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Demographics for the samples are summarized in Table 1. BT participants did not differ from MT or OT participants on gender or number of days employed in the past 30 days. The BT group did significantly differ from the other two groups on race (95.5% African American/other vs. 78.5% for the MT group and 78.7% for the OT group; p < .001) and years of education (11.7 vs. 11.2 years for the MT group and 11.0 years for the OT group; p = .01 and .002, respectively). BT participants were also more likely to be married than OT participants (31% vs. 13%; p = .001) and to be older than MT participants (43.6 vs. 41.8; p = .04).

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Variable | Total sample (N = 417) | Buprenorphine treatment group (n = 132) | Methadone treatment group (n = 191) | Out-of-treatment group (n = 94) | Buprenorphine group vs. methadone group (n = 323) | Buprenorphine group vs. out-of-treatment group (n= 226) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| f (%) | Test statistic | p | Test statistic | p | ||||

| Male | 221 (53.0) | 76 (57.6) | 92 (48.2) | 53 (56.4) | χ2(1)= 2.77 | .096 | χ2 (1)= .032 | .858 |

| Race | χ2 (1)= 18.0 | <.001 | χ2 (1)= 15.1 | <.001 | ||||

| African American | 346 (83.0) | 125 (94.7) | 148 (77.5) | 73 (77.7) | ||||

| White | 67 (16.1) | 6 (4.5) | 41 (21.5) | 20 (21.3) | ||||

| American Indian | 1 (.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (.5) | ||||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1 (.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (.5) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Hispanic | 2 (.4) | 1 (.5) | 1 (.5) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Married | 101 (24.2) | 41 (31.1) | 48 (25.1) | 12 (12.8) | χ2(1)= 1.38 | .241 | χ2(1)= 10.2 | .001 |

| Unemployed for the past 30 days | 311 (74.6) | 101 (76.5) | 134 (70.2) | 76 (80.9) | χ2(1)= 1.59 | .207 | χ2(1)= .608 | .436 |

| M (SD) | ||||||||

| Age | 42.4 (7.6) | 43.6 (6.9) | 41.8 (8.0) | 41.7 (7.6) | F (1,321) = 4.25 | .040 | F (1,224) = 3.61 | .059 |

| Education completed (years) | 11.3 (1.7) | 11.7 (1.6) | 11.2 (1.6) | 11.0 (1.7) | F (1,321) = 6.72 | .010 | F (1,224) = 10.3 | .002 |

Notes: Test statistic for race was obtained by collapsing data into two categories: White (n = 67) versus African American /other (n = 350). Methadone-treatment participants differed from out-of-treatment participants on marital status [χ2 (1)= 5.80, p = .016].

Attitudes toward Methadone and Attitudes toward Buprenorphine Psychometric Characteristics

Internal consistency α scores for the scales were found to be high. For the Attitudes toward Methadone and Buprenorphine scales for the total sample, the values of α were .85 and .87, respectively.

Attitudes toward Methadone and Buprenorphine in the BT Participants

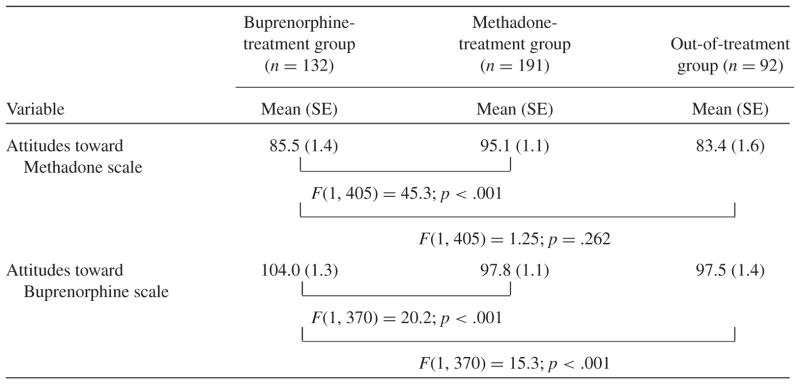

The mean attitude scores across the two measures for buprenorphine participants indicated significantly more positive attitudes toward buprenorphine than toward methadone (p < .001). In comparison with the other groups (see Table 2), BT participants reported significantly less positive attitudes toward methadone than MT participants (p < .001) but did not differ from OT participants (p = .26). Buprenorphine participants had significantly more positive attitudes toward buprenorphine than both MT (p < .001) and OT participants (p < .001).

TABLE 2.

Means (SEs) for scores of Attitudes toward Methadone and Buprenorphine scales for buprenorphine-treatment group versus methadone-treatment group and out-of treatment group.

|

Note: The concomitant variables (covariates) in all analyses were: gender, age, race (White v. African American/ other), marital status (married v. not married), years of education, and prior history of buprenorphine treatment (yes v. no).

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that BT participants rated buprenorphine more favorably than they rated methadone. BT participants also rated buprenorphine more favorably than did MT participants, but rated methadone less favorably than did MT participants. This suggests that individuals seeking short-term BT may have had a preference for buprenorphine over methadone, although it is also possible that they rated buprenorphine higher because it was used for detoxification in the program in which they were enrolling. Because the patients entering MT enrolled in maintenance rather than short-term treatment, it is possible that attitudes toward methadone and buprenorphine were influenced by the participants’ preference for the length of treatment rather than the particular medication.

In 2009, there were significantly more new onset heroin users compared with that in 2002–2008, and a 4.8% increase in non-medical use of prescription opioid analgesics (17). Although not known with precision, it is estimated that only about 20% of the nation’s heroin-addicted adults are in treatment (18). To impact public health, it is important to increase the percentage of opioid-dependent individuals enrolled in effective drug treatments. These individuals may have a preference for methadone or buprenorphine, and these medications may attract different types of patients. Our findings lend support to this notion.

Given the significantly more favorable attitudes toward buprenorphine compared with methadone among participants in this study, it seems advantageous for methadone programs, non-methadone outpatient programs, and physicians providing buprenorphine to explore treatment applicants’ knowledge and attitudes about these medications and determine if they have a preference for one medication. Methadone programs are permitted under US regulations to offer both buprenorphine and methadone, although the higher cost of buprenorphine compared with methadone and the need to administer buprenorphine on a daily basis may make that unfeasible in some cases. Formerly drug-free outpatient programs and physician office practices offering buprenorphine generally are not permitted to provide MT unless they are licensed as an OTP. These providers should form linkages to MT programs so that they can make successful referrals for those individuals who would prefer methadone.

There is growing interest in comparative effectiveness trials given the advent of health-care reform and increasingly cost-conscious payers (19). The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 set aside over $1 billion for comparative effectiveness research (20). The data on attitudes toward methadone and buprenorphine in this study were collected from 2006 to 2008, and many advances in opiate treatment have been made since then. Recent developments such as the approval of an extended-release formulation of naltrexone and an implantable form of buprenorphine offer promising alternatives to existing treatments for opioid-addicted individuals (21,22). It is possible to incorporate patient choice into randomized clinical trials in what are known as patient preference trials (23,24). Where possible, future comparative effectiveness trials with these medications should incorporate patient preference into the design because patient preference in clinical practice (i.e., outside of clinical trials) contributes to selection of treatment approach.

This study has several limitations. The population is primarily African American, a population that has been found to have significant reservations about methadone (4) and so the present findings may not generalize to other groups. Moreover, the buprenorphine participants were significantly more likely to be African American than the methadone and OT participants. Although it is tempting to conjecture that the greater prevalence of African-American participants in BT may represent an aversion to methadone, it may simply be a function of geography, because study participants were drawn from six methadone programs throughout the Baltimore metropolitan area and only one buprenorphine program in a predominantly African-American neighborhood. Additionally, the end of recruitment for the study’s three samples did not perfectly coincide in that the buprenorphine sample’s recruitment ended 5 months after the end of recruitment of the OT sample and 6 months after recruitment ended for the methadone sample. Finally, buprenorphine participants, in contrast to methadone participants, were entering a treatment that was short term (30 days) and intended to result in discontinuing opioid treatment.

CONCLUSION

The Institute of Medicine considers patient choice an important aspect of high-quality health care (25). Prior to the availability of buprenorphine in the United States in 2002, patients seeking opioid agonist treatment were only able to access methadone (and for a limited time Levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM), which is now off the market) through specially licensed OTPs. However, many OT opioid-addicted individuals have negative attitudes toward methadone (3) and, hence, do not seek such treatment. Thus, buprenorphine, lacking the history and mythology that surrounds methadone for many of substance-abusing individuals, may attract individuals who would not agree to take methadone. Future research could examine differences in attitudes between newly enrolling buprenorphine maintenance patients (in both physician offices and clinics) and methadone maintenance patients.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grants R01 DA015842 (PI: Schwartz), DA015842 S (PI: Schwartz), and R01 DA11402 (PI: Katz). Reckitt Benckiser supplied some of the buprenorphine for the study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article

References

- 1.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 04-3939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Mitchell SG, Peterson JA, Reisinger HS, Agar MH, Brown BS. Attitudes toward buprenorphine and methadone among opioid-dependent individuals. Am J Addict. 2008;17(5):396–401. doi: 10.1080/10550490802268835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown BS, Benn GJ, Jansen DR. Methadone maintenance: Some client opinions. Am J Psychiatry. 1975;132(6):623–626. doi: 10.1176/ajp.132.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stancliff S, Myers JE, Steiner S, Drucker E. Beliefs about methadone in an inner-city methadone clinic. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4):571–578. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunt DE, Lipton DS, Goldsmith DS, Strug DL, Spunt B. “It takes your heart”: The image of methadone maintenance in the addict world and its effect on recruitment into treatment. Int J Addict 1985–1986. 20(11–12):1751–1771. doi: 10.3109/10826088509047261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson JA, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Reisinger HS, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Brown BS, Agar MH. Why don’t out-of-treatment individuals enter methadone treatment programs? Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rieckmann T, Daley M, Fuller BE, Thomas CP, McCarty D. Client and counselor attitudes toward the use of medications for treatment of opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swift JK, Callahan JL, Vollmer BM. Preferences. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(2):155–165. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinto H, Maskrey V, Swift L, Rumball D, Wagle A, Holland R. The SUMMIT trial: A field comparison of buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39(4):340–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartz RP, Kelly SM, O’Grady KE, Peterson JA, Reisinger HS, Mitchell SG, Wilson ME, Agar MH, Brown BS. In-treatment vs. out-of-treatment opioid dependent adults: Drug use and criminal history. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34(1):17–28. doi: 10.1080/00952990701653826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz EC, Schwartz RP, King S, Highfield DA, O’Grady KE, Billings T, Gandhi D, Weintraub E, Glovinsky D, Barksdale W, Brown BS. Brief vs. extended buprenorphine detoxification in a community treatment program: Engagement and short-term outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(2):63–67. doi: 10.1080/00952990802585380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peterson JA, Reisinger HS, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Kelly SM, Brown BS, Agar MH. Targeted sampling in drug abuse research: A review and case study. Field Methods. 2008;20(2):155–170. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bower R. Bureau of Social Science Research Report. Vol. 457. Washington, DC: BSSR; 1973. Information and Attitudes about Drugs in DC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4856. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institutes of Health. [Last accessed on January 15, 2011];Fact sheet: Heroin addiction. Available at http://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=123.

- 19.Luce BR, Kramer JM, Goodman SN, Connor JT, Tunis S, Whicher D, Schwartz JS. Rethinking randomized clinical trials for comparative effectiveness research: The need for transformational change. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(3):206–209. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sox HC. Comparative effectiveness research: A progress report. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(7):469–472. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-7-201010050-00269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling W, Casadonte P, Bigelow G, Kampman KM, Patkar A, Bailey GL, Rosenthal RN, Beebe KL. Buprenorphine implants for treatment of opioid dependence: A randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2010;304(14):1576–1583. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard L, Thornicroft G. Patient preference randomised controlled trials in mental health research. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:303–304. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.4.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torgerson DJ, Sibbald B. Understanding controlled trials. What is a patient preference trial? BMJ. 1998;316(7128):360. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine. Improving the Quality for Health Care and Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]