Abstract

Background

Leg ulcers and diabetes-related foot ulcers are frequent and costly complications of their underlying diseases and thus represent a critical issue for public health. Since the population is aging, the prevalence of these conditions will probably increase considerably and require more resources. Treatment of leg and foot ulcers often demands frequent contact with the health care system, may pose great burden on the patient, and involves follow-up in both primary and specialist care. Telemedicine provides potential for more effective care management of leg and foot ulcers. The objective of this systematic review of the literature was to assess the effect of telemedicine follow-up care on clinical, behavioral or organizational outcomes among patients with leg and foot ulcers.

Methods

We searched Ovid MEDLINE (1980–), Ovid EMBASE (1980–), Clinical Trials in the Cochrane Library (via Wiley), Ebsco CINAHL with Fulltext (1981–) and SveMed + (1977–) up to May 2014 for relevant articles. We considered randomized controlled trials, non-randomized trials, controlled before-after studies and prospective cohort studies for inclusion and selected studies according to predefined criteria. Three reviewers independently assessed the included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool. We performed a narrative synthesis of results and assessed the strength of evidence for each outcome using GRADE (grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation).

Results

Only one non-randomized study was included. The study (n = 140) measured the effect of real-time interactive video consultation compared with face-to-face follow-up on healing time, adjusted healing ratio and the number of ulcers at 12 weeks among patients with neuropathic forefoot ulcerations. There were no statistically significant differences in results of the different outcomes between patients receiving telemedicine and traditional follow-up. We assessed the study to have a high risk of bias.

Conclusions

There is insufficient evidence available to unambiguously determine whether telemedicine consultation of leg and foot ulcers is as effective as traditional follow-up.

Keywords: Systematic review, Foot ulcers, Leg ulcers, Telemedicine

Background

Leg ulcers and diabetes-related foot ulcers represent challenges for individual people and the health care system. Leg and foot ulcers are longstanding and costly complications of their underlying diseases and thus represent a critical issue for public health [1]. Since the population is aging, the prevalence of these conditions will probably increase considerably and require more resources [2]. The prevalence of leg ulcers is estimated to be 1.2–3.2% [3]. The annual incidence rate for diabetes-related foot ulcers varies from 1.2%–3.0% [4-6]. An increase in the proportion of older people will affect the need for health care, including the need for treatment and follow-up care of leg and foot ulcers. Although Norway is sparsely populated, with many rural areas, one national target is that health care services be provided as close as possible to the patients’ homes [1,7]. Information and communication technology (ICT) may contribute to achieving this target [2,8].

Telemedicine is a key part of the ICT and is used to achieve integrated health care services in Norway and is defined as “the use of electronic information and communication technologies to provide and support health care when distance separates the participants” [9]. Telemedicine solutions may contribute to improving local health care and to reducing patients’ burden related to traveling to and from treatment venues.

Treatment of leg ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers often demands frequent contact with the health care system and may pose a great burden on the patient [10-12]. Treating diabetic foot ulcers is particularly challenging to health care professionals, because the ulcer might take months to heal, can lead to osteomyelitis, gangrene and amputation [12]. Although leg ulcers patients may not experience the same severe consequences, incorrect implementation of treatment can delay healing and cause pain and trauma [13].

According to international guidelines patients with diabetic foot ulcers should be referred to specialist foot clinics at an early stage [14]. However, in Norway as well as other European countries many foot ulcer patients are treated a substantial time in primary care with lack of expert nurses and doctors and access to specialist health care [10,11,15]. Similarly, patients with leg ulcers are treated to a large extent by primary care nurses, which may be problematic as they may not be using the evidence base sufficiently well to support ulcer healing and patient well-being [13]. A critical point in ulcer care seems to be capacity problems in the specialist health care system and communication problems between primary care and specialist care [11,16].

An additional challenge in countries with many rural areas, such as Norway, is the follow up of these vulnerable patients in specialist health care as they are deemed to have a substantial travel time. The use of telemedicine provides a potential for a more effective management of this patient group due to a more active cooperation between primary and specialist health care, and quicker access to specialist health care when required [17]. Telemedicine follow-up might be an alternative to the current organization of specialist health care to realize the goal of coordinating and integrating care. This may provide positive health gains for patients by reducing travel time and increase their satisfaction with health care.

Telemedicine has been used in health care services for several years, both within disciplines (such as radiology and dermatology), for disease groups (such as diseases of the circulatory and respiratory systems) and for specific diseases such as diabetes [9,18-26]. Previous systematic reviews of the use of telemedicine services for various patient groups included people with diabetes, but not patients with leg and foot ulcers specifically [9,18-26]. One review indicated that telemonitoring improves health care, and documented how telemedicine affects clinical behavioral or organizational outcomes. However, studies involving healthcare providers in the capture and transmission of clinical patient data were not included [26]. Other systematic reviews concluded that the technology is user-friendly and that the quality of the images is adequate for diagnostic purposes [22,24-26]. For more effective management of ulcer care, telemedicine has been suggested as a solution to improve coordination between the different levels of care and to enhance the quality of care in the health care services [26]. However, the effectiveness of telemedicine interventions for patients with leg and foot ulcers regarding clinical, behavioral or organizational outcomes compared with traditional follow-up care is unclear. Health care personnel express a request for telemedicine follow up. Therefore from a clinical and research perspective there is a need to summarize the literature in a systematic review to consider whether telemedicine is adequate to provide appropriate follow-up care of leg and foot ulcers [18,27].

This review assesses whether telemedicine follow-up care of patients with leg and foot ulcers, specifically the transfer of digital still images or video consultations, affects clinical, behavioral or organizational outcomes compared with traditional follow-up care.

Methods

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

Participants

The review examined studies in which patients with arterial, venous and/or diabetes-related foot and/or leg ulcers participated. We considered studies including other types of ulcers if the authors provided separate results for the various types of ulcers.

Intervention

Transfer of digital still pictures or video consultation.

Comparison

Traditional face-to-face follow-up care (hereafter referred to as traditional follow-up).

Outcomes

At least one of the following three main groups of outcomes had to be reported: clinical outcomes (e.g. healing time of the ulcers); behavioral outcomes (e.g. change in degree of self-care or change in interaction between patient and health personnel); or organizational outcomes (e.g. change in interaction and/or cooperation between health personnel).

Study design

We reviewed randomized controlled trials, non-randomized trials, controlled before-after studies and prospective cohort studies with a comparison of treated and non-treated groups. Studies published in English, Norwegian, Swedish or Danish were included. We searched for studies published from 1980 and onwards because relevant telemedical equipment was not available before 1980. We made no attempt to identify grey literature. The protocol is not registered on PROSPERO but is available from MTH on request (in Norwegian).

Search strategy

We performed searches in Ovid MEDLINE (1980–) Ovid EMBASE (1980–), Clinical Trials in the Cochrane Library (via Wiley), Ebsco CINAHL with Fulltext (1981–) and SveMed + (1977–). The first searches were performed in October 2011, while an updated search was performed on May 16th 2014. We developed a search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE and adapted it for the other databases (Table 1). Key search words were “telemedicine”, “video consultation”, “telephone”, “leg ulcer”, “foot ulcer” and “diabetic foot”. We reviewed the reference lists of studies for which we obtained full-text articles and other relevant articles. Experts in the field were contacted to identify unpublished or ongoing studies. We also performed a search for ongoing studies in ClinicalTrials.gov, Current Controlled Trials and Health Services Research Projects in Progress (HSRProj) on June 10th 2014. We did not hand-search key journals.

Table 1.

Search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE

| 1. | Telemedicine/ |

| 2. | Telecommunications/ |

| 3. | Electronic mail/ |

| 4. | Satellite communications/ |

| 5. | Remote consultation/ |

| 6. | Telephone/ |

| 7. | Cellular phone/ |

| 8. | Modems/ |

| 9. | Television/ |

| 10. | Videoconferencing/ |

| 11. | Video recording/ |

| 12. | Webcasts as topic/ |

| 13. | Wireless technology/ |

| 14. | exp Computer communication networks/ |

| 15. | or/1-14 |

| 16. | tele*.tw. |

| 17. | (e-mail* or electronic mail*).tw. |

| 18. | (ehealth* or e-health*).tw. |

| 19. | (e-medicine* or emedicine*).tw. |

| 20. | (videoconferen* or video-conferen*).tw. |

| 21. | (videophone* or video-phone*).tw. |

| 22. | medical record system*.tw. |

| 23. | ((mobile* or phone* or telephone*) adj3 (consult* or counsel*)).tw. |

| 24. | ((mobile* or phone* or telephone*) adj3 (follow up* or support* or interview*)).tw. |

| 25. | (distan* adj4 (health* or consult* or counsel* or monitor*or treatment*)).tw. |

| 26. | (remote* adj4 (health* or consult* or counsel* or monitor* or treatment*)).tw. |

| 27. | image trans*.tw. |

| 28. | picture trans*.tw. |

| 29. | or/16-28 |

| 30. | or/15 or 29 |

| 31. | exp Leg ulcer/ |

| 32. | ((leg or crural or cruris or venous or varicose or stasis or foot or plantar or sole or plantaris or pedis) adj2 (ulc* or sore* or wound*)).tw. |

| 33. | (diabet* adj2 (foot* or feet* or ulc* or sore* or wound*)).tw. |

| 34. | or/31-33 |

| 35. | 30 and 34 |

*The asterisk (*) was used for truncation to search multiple forms of a free-text term (singular/plural, variable spellings, etc.), e.g. “ulc*” to find “ulcer”, “ulcers”, “ulcus”.

Study selection

MTH and MMI independently screened all titles and abstracts identified through the first literature search, while LVN and MMI did the same for the final search. We obtained the full text of articles for all references identified as potentially meeting the inclusion criteria, and also in cases of uncertainty or when there were discrepancies between the reviewers during the screening process. LVN, MTH and MMI independently read all full-text articles followed by discussion to reach consensus.

We contacted the main author of five studies [28-32] by e-mail to obtain additional information about the studies. Four of the studies did not report separate outcome data for ulcer types relevant to the current review. Of these, three authors confirmed that separate data were not available [28,29] or that they did not have the capacity to extract the data [30]. The fourth author provided an incomplete response with regard to separate outcome data. However, she confirmed that telemedicine was used for diagnostic rather than follow-up purposes for the majority of patients included in the study [31]. Consequently, we excluded these four studies [28-31]. We contacted the fifth author because of uncertainty about a subgroup in the study [32]. The author clarified the issue and eventually the study was excluded.

Data collection

We developed a data extraction form to record relevant study characteristics: study design, population characteristics, intervention characteristics, outcome characteristics and results in included studies.

Assessment of risk of bias

LVN, MTH and MMI independently assessed risk of bias in the included studies by using a translated version of the Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool [33]. In regard to the tool’s last item (other potential biases), we specifically assessed potential confounding factors such as previous ulcers, the duration of the ulcers before treatment started, the extent of the ulcer, blood glucose control, malnutrition and mental health [34-39].

Synthesis of the results and quality assessment

We did not perform a meta-analysis as only one study fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Instead, we performed a narrative summary of outcomes presented in the included study and assessed the strength of the evidence for each outcome using the GRADE version 3.6 (grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation) approach to reviewing evidence [40].

Results

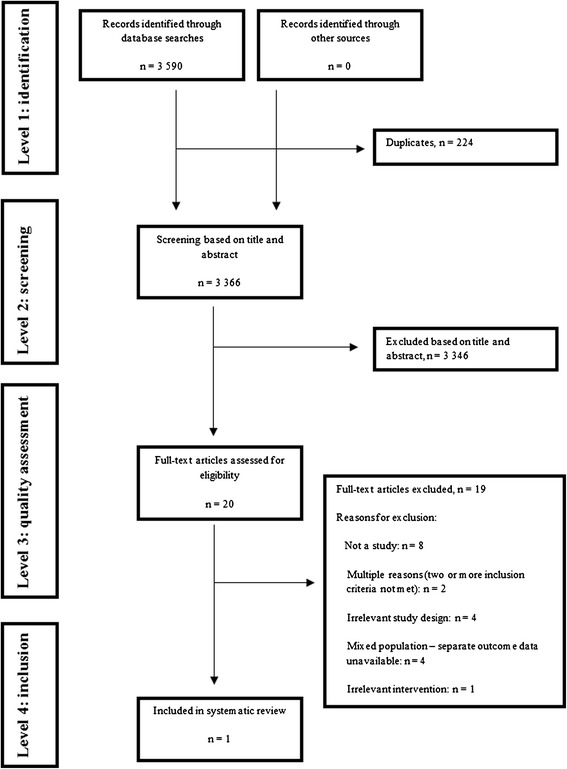

Electronic searches resulted in 3590 citations. Of these, 224 duplicates were removed and 3346 citations were excluded after reviewing the titles and abstracts. We obtained and read the full text of the remaining 20 citations. We excluded 19 citations due to the following reasons: not a study (n = 8), multiple reasons for exclusion (i.e. more than one inclusion criteria not met; n = 2), irrelevant study design (n = 4), mixed population and separate outcome data not available (n = 4), and irrelevant intervention (n = 1). Details for excluded studies in all but the first exclusion category are provided in Table 2 [28-32,41-46]. Contact with experts did not identify further studies. Eventually, only one study [47] was included in the review (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Characteristics of excluded studies

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bowles 2002 [28] | Population: Diabetes patients with and without foot ulcers. Separate data for foot ulcers not available. |

| Dobke 2008 [30] | Population: Mixed, including patients with pressure ulcers. Separate data for venous/arterial leg ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers not available. |

| Edmondson 2010 [41] | Study design: uncontrolled before-after study |

| Edwards 2009 [42] | Intervention: not telemedicine follow-up |

| Hands 2006 [31] | Population: Mixed, separate data for venous/arterial leg ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers not provided by author. Author confirmed that telemedicine was used for diagnostic purposes rather than follow-up in the majority of patients. |

| Kim 2004 [32] | Study design: Prospective cohort study without comparison of exposed (telemedicine follow-up) and non-exposed (no telemedicine follow-up) patients. |

| Lazzarini 2010 [43] | Study design: Multiple case study |

| Manuel 2012 [44] | Study design: Uncontrolled before-after study |

| Nagykaldi 2003 [45] | Study design: Uncontrolled before-after study |

| Population: Diabetes patients. Separate data for ulcers not available. | |

| Nyheim 2010 [46] | Study design: Qualitative study |

| Outcomes: Change in knowledge about chronic ulcers among nurses. | |

| Santamaria 2004 [29] | Population: Mixed, including pressure ulcers and surgical ulcers. Separate data for foot and leg ulcer patients not available. |

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection process.

The search for ongoing studies resulted in three titles and projects that might be included in a future systematic review regarding the effect of telemedicine follow-up of foot and leg ulcers (Table 3).

Table 3.

Ongoing trials likely to meet inclusions criteria

| Study/source | Country | Study design | Population | Treatment | Trial start/likely completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clin. Trials.gov NCT01608425 | Denmark | Randomized study | People with diabetes-related foot ulcers | Telemedicine consultations between ulcer-nurses in the primary sector and the wound clinics at the hospitals in the region. | 2011/2013 |

| Clin. Trials.gov NCT01710774 | Norway | Cluster randomized study (non-inferiority) | People >20 years with diabetes-related foot ulcers enrolled in specialist health care | Telemedicine follow-up care in municipal primary health care in collaboration with specialist health care | 2012/2016 |

| Clin. Trials.gov NCT01814267 | France | Randomized study | People with diabetes-related foot ulcers ≥18 years enrolled in specialist health care | Telemedicine care and follow-up in specialist health care | 2013/2015 |

Study characteristics

Table 4 gives an overview of the characteristics of the included study. The study was a non-randomized study conducted in the United States and comprised 140 people with diabetes-related foot ulcers. The purpose of the study was to compare the effectiveness of telemedicine follow-up of forefoot ulcerations with traditional face-to-face follow-up with regard to healing time [47].

Table 4.

Characteristics of the included study

| Study, year (country) | Design | Setting | Study population | Intervention group | Control group | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilbright, 2004 [47] | Non-randomized study | Two local medical centers located 55 miles apart | Total: 140 patients | Real time interactive video consultation, with or without transfer of digital images | Face-to-face follow-up in a specialized diabetes-related foot program | Healing time in days, percentage of ulcer healed after 12 weeks and healing time ratio adjusted for age, ulcer duration (days), location, size, crossover and severity grade | Average healing time in days: Intervention group = 43.2 ± 29.3 |

| (USA) | Intervention group: 20 patients (55% women, average age 55.1 years) | Control group = 45.5 ± 43.4 | |||||

| P = 0.83 | |||||||

| Control group: 120 patients (45% women, average age 56.5 years) | Adjusted ratio for healing time: Intervention group = 1.00 | ||||||

| Control group = 1.40 | |||||||

| P = 0.10 | |||||||

| Percentage of ulcers healed at 12 weeks: Intervention group = 75% | |||||||

| Control group = 81% | |||||||

| P = 0.55 | |||||||

| Not healed or lost to follow-up: Intervention group: 3/20 | |||||||

| Control group: 7/120 | |||||||

| No patient adverse effects were reported. |

Participants

The study included 140 consecutive patients treated for neuropathic forefoot ulcerations from two medical centers. The patients from one center, the intervention group, comprised 20 patients treated via telemedicine consultation (55% women, average age 55.1 years). The other center, the control group, comprised 120 patients receiving traditional follow-up (45% women, average age 56.5 years).

Intervention

The intervention group received real-time interactive video consultation, with or without transfer of digital images of forefoot ulcerations, with a specialist nurse, physician and physiotherapist based at a remote medical center. The patients in the control group were treated face-to-face according to a specialized diabetes-related foot program at a local medical center. Both groups were given a standard follow-up program including routine follow-up, screening of the feet, lectures, guidance and adaptation of footwear [47]. The number of consultations per person for the intervention group or the control group was not stated. The patients were followed up for 12 weeks.

Outcome

The main outcomes were forefoot ulcer healing time in days, the percentage of ulcers healed after 12 weeks and healing time ratio adjusted for age, ulcer duration (days) location, size, crossover and severity grade. The authors did not report any adverse events or stated whether they assessed adverse events related to telemedicine follow-up.

Risk of bias

We consider the risk of bias in the study to be high (Table 5), mainly due to the lack of randomization of participants to the intervention and control group. The participants and health personnel could not be blinded to the type of treatment received. In addition, the article does not state whether the outcome assessors were independent and blinded [47].

Table 5.

Assessment of risk of bias in the included study

| Domain | Study |

|---|---|

| Wilbright et. al. [47] | |

| Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? | No |

| Was allocation adequately concealed? | No |

| Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented by participants and personnel during the study? | No |

| Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented by outcome assessors during the study? | Unclear |

| Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? | No |

| Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? | No |

| Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias? | Yes |

| Overall risk for bias | High risk |

Unclear = the risk of bias is unknown, or not relevant to the study. No = high risk of bias. Yes = low risk of bias.

The number of patients who either did not heal or were lost to follow-up was 3 of 20 (15%) in the telemedicine group and 7 of 120 (5%) in the control group. The researchers analyzed the healing time for dropout patients as censored events at 12 weeks of follow-up. It is unclear how the researchers analyzed patients who did not heal at 12 weeks.

The researchers made corrections for important confounders, for example healing time ratio was adjusted for age, ulcer severity, ulcer duration, location and size. The small sample size might not allow adjusting for other potential confounding factors.

Study results

The unadjusted forefoot healing time for the telemedicine group and the control group: 43.2 ± 29.3 days for the telemedicine group versus 45.5 ± 43.4 days for the control group (P = 0.83) did not statistically significant differ. After adjusting for age, ulcer duration, location, size, crossover and severity grade, the intervention group and the control group did not statistically significant differ in healing ratio (1.40 versus 1.00, P = 0.10). Moreover, there were no statistically significant differences between groups in the number of ulcers healed at 12 weeks: 75% in the intervention group and 81% in the control group (P = 0.55) [47].

Using GRADE, we consider the strength of the evidence to be very low for all outcomes (Table 6). A high risk of bias due to limitations in the study design was the main reason why the study achieved a very low GRADE score.

Table 6.

GRADE assessment of the efficacy of video consultation of patients with leg and foot ulcers

| Number of participants (study) | Outcome | Comparison | Study design | Quality assessment (risk of bias) | Consistency | Directness | Precision | Reporting bias | Result | GRADE assessment | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140 [47] | Unadjusted healing time (number of days) | Traditional consultation with diabetes-related foot team | 2 | −2 | 0 | 0 | −2 | 0 | Intervention group: 43.5 ± 29.3 | Very low | Degraded because of the study design, high risk of bias and uncertain estimate of effectiveness |

| Control group: 45.5 ± 43.4 | |||||||||||

| P =0.83 | |||||||||||

| 140 [47] | Adjusted healing time | Traditional consultation with diabetes-related foot team | 2 | −2 | 0 | 0 | −2 | 0 | Intervention group: 1.40 | Very low | Degraded because of the study design, high risk of bias and uncertain estimate of effectiveness |

| Control group: 1.00 | |||||||||||

| P = 0.10 | |||||||||||

| 140 [47] | Ulcers healed at 12 weeks | Traditional consultation with diabetes-related foot team | 2 | −2 | 0 | 0 | −2 | 0 | Intervention group: 75% | Very low | Degraded because of the study design, high risk of bias and uncertain estimate of effectiveness |

| Control group: 81% | |||||||||||

| P =0.55 |

Discussion

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review with the purpose of summarizing studies measuring the effectiveness of telemedicine follow-up care of patients with leg and foot ulcers. The evidence that we identified [47] still renders it inconclusive whether telemedicine management of people with diabetes-related foot ulcers may be an equivalent alternative to traditional follow-up concerning the healing time of the ulcers. The strength of the evidence is very low and limited by the study design: a high risk of systematic bias, insufficient and partly inadequate reporting of predefined outcome values and few participants especially in the intervention group.

Randomized controlled trials with larger samples and sufficient follow-up time are needed to produce valid evidence about the effectiveness of telemedicine follow-up care of leg and foot ulcers. Even though health care services have used telemedicine for several years, studies that evaluate the effect of telemedicine have been limited to small-scale studies conducted over short periods of time [19]. Telemedicine interventions are complex and require considerable resources to carry out. Moreover, change in health care systems is slow and needs time to adapt and adopt new technologies. Thus, the time frame employed by Wilbright et al. [47], and other researchers [19] may have been too short to enable telemedicine technology to be adopted in the study settings and to evaluate effectiveness in randomized controlled trials.

A telemedicine intervention in patients with leg and foot ulcers can be considered to be a “complex intervention” as several components interact within the experimental and control group [48]. Challenges in developing, evaluating and synthesizing complex telemedicine interventions are for example the number of nurses involved in patient care and the different behaviors by those delivering the intervention. Telemedicine interventions also target at least two organizational levels, including primary health care and specialist health care. A strict standardization of telemedicine interventions may thus prove difficult and the intervention may be challenging to replicate and generalize across settings and studies. Accordingly, authors should carefully describe all components of the intervention when reporting future randomized studies. Furthermore, future intervention studies should standardize outcome measures [19,49], although defining explicit outcome criteria for treating ulcers is a challenge due to aetiology of wounds and multiple ways of assessing improvement, including wound-healing related outcomes (wound closure, reduction rate and healing time) and change in wound condition [49]. Adding to this challenge is the fact that patients with diabetes foot ulcers are fragile, have a relatively high age, comorbidites, and excess mortality [50]. Altogether these factors may explain why studies are lacking that evaluate the effectiveness of telemedicine follow-up of patients with leg and foot ulcers.

When randomizing patients at an individual level the same health professionals will treat patients in the intervention group and control group. This may threaten the validity of the study. Thus, in future research, there is a rationale for choosing cluster randomized trials where units such as geographical areas or institutions, are allocated to the different groups, [51]. A cluster randomized trial will therefore require a larger sample size as it will have to take into account dependency in data. Furthermore, an equivalence or non-inferiority design may be more suitable for establishing whether telemedicine is as effective as usual care in the follow-up of leg and foot ulcers.

One could argue that evidence from studies of telemedicine interventions in other disease fields should be used to inform implementation of telemedicine in the follow-up of leg and foot ulcers. For example, telemonitoring approaches have been found therapeutically effective in chronic heart failure and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease [8]. Moreover, telemedicine interventions have been found moderately effective in reducing the risk of disease-related hospitalizations in patients with diabetes and asthma [22,23], although studies were small and conducted over short periods of time. Nevertheless, patients with foot and leg ulcers present a complex group of patients in clinical practice that might require specific adaptations of the telemedicine follow-up. Thus, we argue the need for further trials on these particular patients groups, preferably in separate trials due to somewhat different ulcer aetiologies, standards of care and response to therapy [49].

Safety issues and adverse effects are important aspects to consider when evaluating the effectiveness of telemedicine, including follow –up of patients with leg and foot ulcers. In spite of the promises and benefits that telemedicine is capable of delivering, there are numeral challenges at patient, technical, and legal level. For example, telemedicine may alter the relationship between patients and health professionals compared to face-to-face, in-the-same-room encounters that are typical in usual care settings [52]. Moreover, lack of competence among health professional hinder efficient implementation and might result in adverse events among those receiving care. Another significant concern about telemedicine is that the system must be secured, to prevent unauthorized access to the information. Legal regulations are therefore important but need to balance security without becoming a hurdle to implementation [52]. Safety issues and adverse events were not reported in the included study [48]. These matters are also infrequently reported in systematic reviews of telemedicine interventions [8] and should thus be addressed in future studies.

A key question in evaluating complex telemedicine interventions is whether they are effective in everyday practice [48]. In response to this key issue, we present implications for further research to evaluate the effectiveness of telemedicine interventions in leg and foot ulcers using the EPICOT format [53] (Table 7). We describe a complex intervention aiming for a new service model that incorporates telemedicine, emphasizing clinical outcomes. A second key question is how the intervention works: what are the active ingredients and how are they exerting their effect? [48]. Therefore, it will be important to investigate the impact of the service in both primary and specialist health care using qualitative research methods. Such process evaluation should also explore the experiences of patients and clinicians, and priorities of policy makers in the use of telemedicine.

Table 7.

Research recommendations for future studies on the effect of telemedicine follow-up care of leg and foot ulcers based on EPICOT format

| Issues to consider | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Core elements | |||

| E | Evidence | What is the current evidence? | One small study (n = 140) with a non-randomized design conducted in the United States. |

| P | Population | Patients (>20 years) presenting a leg ulcer or diabetes-related foot ulcer to specialist health care. | |

| I | Intervention | Telemedicine follow-up care provided by municipal primary health care in collaboration with specialist health care | |

| C | Comparison | Placebo, routine care, alternative treatment/management | Care as usual. |

| O | Outcome | Which clinical or patient related outcomes will the researcher need to measure, improve, influence or accomplish? Which methods of measurement should be used? | Healing time; total number of consultations per person; sequelae directly related to the foot or leg ulcer: infection, hospitalization, and vascular surgery during the study; patient satisfaction with health care; health status and cost utility; the time elapsing before a new ulcer appears, the incidence of amputation and survival. |

| T | Time stamp | Date of literature search or recommendation | May 16th, 2014. |

| Optional elements | |||

| d | Disease burden | Leg ulcers and diabetes-related foot ulcers are longstanding and costly complications of their underlying diseases and represent challenges for individual people and health care system. Treatment of leg ulcers and diabetic foot ulcers often demands frequent contact with the health care system and may pose a great burden on the patient. According to international guidelines patients with leg or foot ulcers should be referred to specialist foot clinics at an early stage. However, in Norway as well as other European countries many foot ulcer patients are treated a substantial time in primary care with lack of expert nurses and doctors and access to specialist health care, which may be problematic as they may not be using the evidence base sufficiently well to support ulcer healing and patient well-being. | |

| t | Timeliness | Time aspects of core elements: | |

| Mean age of the population | 67 years | ||

| Duration of the intervention | 12 months | ||

| Length of follow-up | 3 years | ||

| s | Study type | What is the most appropriate study design to address the proposed question | Cluster- randomized controlled trial |

Conclusion

The systematic review assessed whether telemedicine follow-up care of patients with leg and foot ulcers positively affected clinical, behavioral and organizational outcomes compared with traditional follow-up. We only identified one small non-randomized study that met the inclusion criteria, but lacked rigor. Thus the available evidence is too weak to make conclusions about the effectiveness of telemedicine follow-up care of patients with leg and foot ulcers. Larger and more rigorous studies are needed to enable strong conclusions and clinical recommendations to be made.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions for improvement. This project was funded by Bergen University College, Norway. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Abbreviation

- ICT

Information and communication technology

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors collaborated on the protocol, read abstracts, selected studies for full text assessment, reviewed articles and critically appraised included studies. MTH and LVN performed the literature searches. MTH wrote the draft of the first manuscript, MMI and LVN made substantial revisions and re-wrote the final manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Contributor Information

Lena Victoria Nordheim, Email: lvn@hib.no.

Marianne Tveit Haavind, Email: marianne@henanger.com.

Marjolein M Iversen, Email: miv@hib.no.

References

- 1.Armstrong DG, Kanda VA, Lavery LA, Marston W, Mills JL, Boulton AJM. Mind the Gap: disparity between research funding and costs of care for diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1815–1817. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services . St. Meld. nr. 47 (2008–2009) Samhandlingsreformen. Rett Behandling – på Rett Sted – til Rett tid. [in Norwegian] [Report to the Storting White Paper No. 47 (2008–2009) The Coordination Reform. Right Treatment – at the Right Place - at the Right Time] Oslo: Ministry; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graham I, Harrison M, Nelson E, Lorimer K, Fisher A. Prevalence of lower-limb ulceration: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2003;16:305–316. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200311000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbott CA, Carrington AL, Ashe H, Bath S, Every LC, Griffiths J, Hann AW, Hussein A, Jackson N, Johnson KE, Ryder CH, Torkington R, Van Ross ER, Whalley AM, Widdows P, Williamson S, Boulton AJ, North-West Diabetes Foot Care Study The North-West diabetes foot care study: incidence of, and risk factors for, new diabetic foot ulceration in a community-based patient cohort. Diabetic Medicine. 2002;19:377–384. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller IS, de Grauw WJC, van Gerwen WHEM, Bartelink ML, van Den Hoogen HJM, Rutten GEHM. Foot ulceration and lower limb amputation in type 2 diabetic patients in dutch primary health care. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:570–574. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey S, Newton K, Blough D, McCulloch D, Sandhu N, Reiber G, Wagner E. Incidence, outcomes, and cost of foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:382–387. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norwegian Ministry of health and care services . St. Meld. nr. 16 (2010–2011) Nasjonal Helse- og Omsorgsplan (2011–2015). [in Norwegian] [Report to the Storting White Paper No. 16 (2010–2011) National Health and Care Plan (2011–2015)] Oslo: Ministry; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekeland AG, Bowes A, Flottorp S. Effectiveness of telemedicine: a systematic review of reviews. International Journal of Medical Informas. 2010;79:736–771. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Committee on Evaluating Clinical Applications of Telemedicine . A Guide to Assessing Telecommunication in Health Care. Washington D.C: National Acadamy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prompers L, Huijberts M, Apelqvist J, Jude E, Piaggesi A, Bakker K, Edmonds M, Holstein P, Jirkovska A, Mauricio D, Tennvall GR, Reike H, Spraul M, Uccioli L, Urbancic V, Van Acker K, Van Baal J, Van Merode F, Schaper N. Delivery of care to diabetic patients with foot ulcers in daily practice: results of the Eurodiale Study, a prospective cohort study. Diabetic Medicine. 2008;25:700–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribu L, Wahl A. How patients with diabetes who have foot and leg ulcers perceive the nursing care they receive. Journal of Wound Care. 2004;13:65–68. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2004.13.2.26578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Battum P, Schaper N, Prompers L, Apelqvist J, Jude E, Piaggesi A, Bakker K, Edmonds M, Holstein P, Jirkovska A, Mauricio D, Ragnarson Tennvall G, Reike H, Spraul M, Uccioli L, Urbancic V, van Acker K, van Baal J, Ferreira I, Huijberts M. Differences in minor amputation rate in diabetic foot disease throughout Europe are in part explained by differences in disease severity at presentation. Diabetic Medicine. 2011;28:199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ylönen M, Stolt M, Leino-Kilpi H, Suhonen R. Nurses’ knowledge about venous leg ulcer care: a literature review. International Nursing Review. 2014;61:194–202. doi: 10.1111/inr.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulton AJ, Armstrong DG, Albert SF, Frykberg RG, Hellman R, Kirkman MS, Lavery LA, Lemaster JW, Mills JL, Sr, Mueller MJ, Sheehan P, Wukich DK, American Diabetes Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: a report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the AmericanDiabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1679–1685. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clemensen J, Larsen SB, Kirkevold M, Ejskjaer N: Treatment of diabetic foot ulcers in the home: video consultations as an alternative to outpatient hospital care.International J Telemedicine and Applications; 2008: doi:10.1155/2008/132890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Iversen MM, Hausken MF, Katrine Vetlesen: Diabetes fotsår. Utvikling av nye telemedisinske systemer/ produkter [in Norwegian]. Diabetes foot ulcers. Development of new telemedicine systems/ products; 2012. [http://www.innomed.no/media/media/prosjekter/rapporter/59_-_Telemedisinsk_oppfolging_av_diabetes_fotsar.pdf]

- 17.McGill M, Constantino M, Yue DK. Integrating telemedicine into a national diabetes footcare network. Practical Diabetes International. 2000;17:235–238. doi: 10.1002/1528-252X(200010)17:7<235::AID-PDI101>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currell R, Urquhart C, Wainwright P, Lewis R: Telemedicine versus face to face patient care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, (2). Art. No.: CD002098. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002098. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ekeland A, Bowes A, Flottorp S. Methodologies for assessing telemedicine: a systematic review of reviews. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2012;81:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hersh WR, Hickam DH, Severance SM, Dana TL, Krages KP, Helfand M. Diagnosis, access and outcomes: update of a systematic review of telemedicine services. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2006;12(Suppl 2):S3–S31. doi: 10.1258/135763306778393117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson CL, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Batts-Turner ML, Gary TL. A systematic review of interactive computer-assisted technology in diabetes care. Interactive information technology in diabetes care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:105–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaana M, Paré G. Home telemonitoring of patients with diabetes: a systematic assessment of observed effects. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2007;13:242–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLean S, Chandler D, Nurmatov U, Liu J, Pagliari C, Car J, Sheikh A: Telehealthcare for asthma.Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, (10). Art. No.: CD007717. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007717.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Paré G, Jaana M, Sicotte C. Systematic review of home telemonitoring for chronic diseases: the evidence base. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2007;14:269–277. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhoeven F, van Gemert-Pijnen L, Dijkstra K, Nijland N, Seydel E, Steehouder M: The contribution of teleconsultation and videoconferencing to diabetes care: a systematic literature review.Journal of Medical Internet Research 2007, 9:e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Verhoeven F, Tanja-Dijkstra K, Nijland N, Eysenbach G, van Gemert-Pijnen L. Asynchronous and synchronous teleconsultation for diabetes care: a systematic literature review. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2010;4:666–684. doi: 10.1177/193229681000400323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsen SB. Diabetes og telemedicin. Ugeskrift for Læger. 2010;172:2034–2040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowles KH, Dansky KH. Teaching self-management of diabetes. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2002;20:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Santamaria N, Carville K, Ellis I, Prentice J. The effectiveness of digital imaging and remote expert wound consultation on healing rates in chronic lower leg ulcers in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. Primary Intention: The Australian Journal of Wound Management. 2011;12:62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dobke MK, Bhavsar D, Gosman A, De Neve J, De Neve B. Pilot trial of telemedicine as a decision aid for patients with chronic wounds. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2008;14:245–249. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2007.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hands LJ, Clarke M, Mahaffey W, Francis H, Jones RW. An e-health approach to managing vascular surgical patients. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 2006;12:672–680. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HM, Lowery JC, Hamill JB, Wilkins EG. Patient attitudes toward a web-based system for monitoring chronic wounds. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 2004;10(Suppl. 2):S-26–S-34. doi: 10.1089/1530562042632074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions Version 510 [updated March 2011] London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2012. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(Suppl.1):S11–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc12-s011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Claudi T, Abramhamsen R, Andersen S, Basharat F, Birkeland K, Cooper J, Furuseth K, Hanssen K, Hausken M, Jenum A, Dahl Jørgensen K, Lorentsen N, Midthjell K, Næbb H. Nasjonale Faglige Retningslinjer Diabetes, Forebygging, Diagnostikk og Behandling [in Norwegian] National Guidelines Diabetes. Prevention, Diagnostics and Treatment. Oslo: Helsedirektoratet; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prompers L, Huijberts M, Apelqvist J, Jude E, Piaggesi A, Bakker K, Edmonds M, Holstein P, Jirkovska A, Mauricio D, Tennvall GR, Reike H, Spraul M, Uccioli L, Urbancic V, Van Acker K, Van Baal J, Van Merode F, Schaper N. Optimal organization of health care in diabetic foot disease: introduction to the Eurodiale study. International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds. 2007;6:11–17. doi: 10.1177/1534734606297245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolis D, Allen-Taylor L, Hoffstad O, Berlin J. Diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers: predicting which ones will not heal. American Journal of Medicine. 2003;115:627–631. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Wound Management Association . Position Document. Hard-to-Heal Wounds: A Holistic Approach. London: MEP Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams LH, Rutter CM, Katon WJ, Reiber GE, Ciechanowski P, Heckbert SR, Lin EHB, Ludman EJ, Oliver MM, Young BA, Von Korff M. Depression and incident diabetic foot ulcers: a prospective cohort study. American Journal of Medicine. 2010;123:748–754. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.GRADEpro . [Computer program on www.grade.org]. Version June 2014. Hamilton: McMaster University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edmondson M, Prentice J, Fielder K, Mulligan S. WoundsWest advisory service pilot: an innovative delivery of wound management. Wound Practice & Research. 2010;18:180–188. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Shuter P, Lindsay E. A randomised controlled trial of a community nursing intervention: improved quality of life and healing for clients with chronic leg ulcers. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18:1541–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazzarini PA, Clark D, Mann RD, Perry RD, Thomas CJ, Kuys SS. Does the use of store-and-forward telehealth systems improve outcomes for clinicians managing diabetic foot ulcers? A pilot study. Wound Practice & Research. 2010;18:164–172. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manuel P. A prospective, interventional study of the effectiveness of digital wound imaging, remote consultation and podiatry offloading devices on the healing rates of chronic lower extremity wounds in remote regions of Western Australia. Wound Practice & Research. 2012;20:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW. Diabetes patient tracker, a personal digital assistant-based diabetes management system for primary care practices in Oklahoma. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 2003;5:997–1001. doi: 10.1089/152091503322641051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nyheim B, Lotherington AT, Steen A. Nettbasert sårveiledning. Kunnskapsutvukling og bedre mestring av leggsårbehandling i hjemmetjenesten [in Norwegian]. [Online wound guidance. Knowledge development and better management of leg wound treatment in home care] Nordisk Tidsskrift for Helseforskning. 2010;6:40–55. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilbright WA, Birke JA, Patout CA, Varnado M, Horswell R. The Use of telemedicine in the management of diabetic-related foot ulceration: a pilot study. Advances in Skin and Wound Care. 2004;17:232–238. doi: 10.1097/00129334-200406000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M: Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance.BMJ 2008, 337:a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Gottrup F, Apelqvist J, Price P, European Wound Management Association Patient Outcome Group Outcomes in controlled and comparative studies on non-healing wounds: recommendations to improve the quality of evidence in wound management. Journal of Wound Care. 2010;19:237–268. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2010.19.6.48471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iversen MM, Tell GS, Riise T, Hanestad BR, Østbye T, Graue M, Midthjell K. History of foot ulcer increases mortality among individuals with diabetes: a ten year follow-up of the Nord-Trøndelag health study, Norway. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2193–2199. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fayers PM, Jordhoy MS, Kaasa S. Cluster-randomized trials. Palliative Medicine. 2002;16:69–70. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm503xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matusitz J, Breen GM. Telemedicine: its effects on health communication. Health Communun. 2007;21:73–83. doi: 10.1080/10410230701283439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brown P, Brunnhuber K, Chalkidou K, Chalmers I, Clarke M, Fenton M, Forbes C, Glanville J, Hicks NJ, Moody J, Twaddle S, Timimi H, Young P. How to formulate research recommendations. BMJ. 2006;333:804–806. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38987.492014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]