Abstract

Background

Meat from Bos taurus and Bos indicus breeds are an important source of nutrients for humans and intramuscular fat (IMF) influences its flavor, nutritional value and impacts human health. Human consumption of fat that contains high levels of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) can reduce the concentration of undesirable cholesterol (LDL) in circulating blood. Different feeding practices and genetic variation within and between breeds influences the amount of IMF and fatty acid (FA) composition in meat. However, it is difficult and costly to determine fatty acid composition, which has precluded beef cattle breeding programs from selecting for a healthier fatty acid profile. In this study, we employed a high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chip to genotype 386 Nellore steers, a Bos indicus breed and, a Bayesian approach to identify genomic regions and putative candidate genes that could be involved with deposition and composition of IMF.

Results

Twenty-three genomic regions (1-Mb SNP windows) associated with IMF deposition and FA composition that each explain ≥ 1% of the genetic variance were identified on chromosomes 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 17, 26 and 27. Many of these regions were not previously detected in other breeds. The genes present in these regions were identified and some can help explain the genetic basis of deposition and composition of fat in cattle.

Conclusions

The genomic regions and genes identified contribute to a better understanding of the genetic control of fatty acid deposition and can lead to DNA-based selection strategies to improve meat quality for human consumption.

Keywords: Fatty acid, GWAS, Bos indicus, Beef, Positional candidate gene

Background

Many consumers associate consumption of fat from beef with coronary heart disease, diabetes and obesity, due to the presence of cholesterol, high concentration of saturated fatty acids (SFA), and low concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). However, consumption of fatty acids is necessary for human nutrition [1]. Beef has high nutritional value from children to seniors, is a rich source of protein (essential amino acids), iron, zinc, B vitamins and essential polyunsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic and linolenic acid [2]. Beef fat also has a high concentration of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), whose melting point is low and can reduce the concentration of bad cholesterol (LDL) in blood circulation [3].

The amount of fatty acid and its composition in beef varies by breed, nutrition, sex, age and carcass finishing level [4]. The difficulties associated with determining intramuscular fat (IMF) deposition and composition as well as the limited knowledge on the genetic mechanisms that control these traits has limited genetic progress in the production of healthier beef.

The development of high-density bovine genotyping [5] and their use in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have allowed identification of genomic regions associated with phenotypes of interest. The technique of GWAS exploits differences in allele frequencies of thousands of polymorphic markers available in unrelated individuals who possess different phenotypes (for example, deposition and composition of intramuscular fat), and leads to the identification of markers associated with a given phenotype [6]. Bayesian approaches have been applied to GWAS to detect significant quantitative trait loci (QTL) for traits of economic importance. One such approach uses multiple regression (evaluating marker effects simultaneously), treating marker effects as random to reduce overestimation bias of significant QTL effects, generating the actual posterior distribution of QTL effects given the data which can provide richer inference than can be obtained by simply constructing p-values as well as providing an alternative to the use of p-values to avoid false positives [7-9].

Brazilian beef is exported and consumed in more than 100 countries [10]. Purebred and crossbred Nellore cattle, which are of Bos indicus descent, are the predominant source of beef in Brazil. Previous research has documented that muscle and fat tissues from Bos indicus cattle develop in a different manner than in Bos taurus breeds [11-14]. However, studies documenting the genetics of fatty acid deposition and composition in Bos indicus breeds are limited.

In this study we performed a GWAS using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chips (770 k) and Bayesian methods (Bayes B) to identify genomic regions associated with fat deposition and fatty acid composition (FA) in Nellore beef.

Results and discussion

Intramuscular fat deposition and composition

Modern consumers are concerned with their overall health and often desire to reduce their caloric intake. This has increased the demand for lean meat production with a healthier fatty acid composition, which would comprise a lower proportion of SFA and greater proportion of MUFA. The amount of fat deposition in meat represented as IMF (mean = 2.77%) reported in this feedlot-finished study was greater than for pasture-finished counterparts, as expected, but lower than normally observed in Continental and English breeds [15-17]. Despite of that, IMF observed in this work was within limits of reasonable amount of fat to assure acceptable quality levels for consumers according to Nuernberg et al. [18].

The fatty acid composition observed for the most abundant FAs were: C14:0 at 3.54%, C16:0 at 26.69%, C18:0 at 14.98%, C16:1 cis-9 at 3.31%, C18:0 at 14.98%, C18:1 cis-9 at 37.46%, C18:2 cis-9 cis 12 at 1.60%, SFA at 47.23%, MUFA at 48.34%, and PUFA at 2.87% (Table 1). The proportion of MUFA was higher than SFA, and oleic acid (C18:1 cis-9) was the most abundant single fatty acid (37.46%).The FA composition presented in this work is similar to those reported in the literature for Nellore or other Bos indicus breeds [19-21]. This population also presented, in relation to Bos taurus breeds, average composition of fatty acids which is in agreement with reports from the USDA [22]. However, in this study a lower quantity of PUFA was observed in general, but not for C18:2 cis-9 trans-11, consequently a lower ratio of PUFA/SFA (6.08%). Similar MUFA and PUFA results have been reported in previous studies that utilized Bos indicus steers [20,23].

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics, variance components and heritability by GBLUP for IMF deposition and composition in Nellore

| Trait | Terminology 1 | N | Mean ± SE 2 | Genetic variance | Residual variance | Total variance | h2 ± SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMF (%) |

Intramuscular fat |

382 |

2.77 ± 0.05 |

0.196 |

0.490 |

0.686 |

0.29 ± 0.16 |

| C12:0 (mg/mg) |

Lauric acid |

374 |

0.07 ± 0.001 |

0.000039 |

0.00072 |

0.000761 |

0.05 ± 0.09 |

| C14:0 |

Myristic acid |

378 |

3.54 ± 0.03 |

0.0530 |

0.250 |

0.303 |

0.17 ± 0.11 |

| C14:1 cis-9 |

Myristoleic acid |

378 |

0.96 ± 0.01 |

0.0076 |

0.041 |

0.0486 |

0.16 ± 0.11 |

| C15:0 |

Pentadecylic acid |

378 |

0.80 ± 0.02 |

0.0 |

0.052 |

0.052 |

0 ± 0.06 |

| C16:0 |

Palmitic acid |

378 |

26.69 ± 0.15 |

0.6070 |

7.068 |

7.675 |

0.08 ± 0.10 |

| C16:1 cis-9 |

Palmitoleic acid |

378 |

3.31 ± 0.04 |

0.0640 |

0.354 |

0.418 |

0.15 ± 0.10 |

| C17:0 |

Margaric acid |

378 |

1.07 ± 0.009 |

0.0061 |

0.019 |

0.0251 |

0.24 ± 0.15 |

| C17:1 |

Heptadecenoic acid |

378 |

0.58 ± 0.007 |

0.0024 |

0.009 |

0.0114 |

0.20 ± 0.12 |

| C18:0 |

Stearic acid |

378 |

14.98 ± 0.14 |

1.3380 |

5.348 |

6.686 |

0.20 ± 0.12 |

| C18:1 cis-9 |

Oleic acid |

378 |

37.46 ± 0.22 |

2.0720 |

10.826 |

12.898 |

0.16 ± 0.11 |

| C18:1 cis-11 |

Cis-Vaccenic acid |

378 |

2.98 ± 0.05 |

0.0850 |

0.357 |

0.442 |

0.02 ± 0.09 |

| C18:1 cis-12 |

Cis-12 Octadecenoic |

377 |

0.91 ± 0.02 |

0.0030 |

0.034 |

0.037 |

0.09 ± 0.10 |

| C18:1, cis-13 |

Cis-13 Octadecenoic |

377 |

0.58 ± 0.008 |

0.0 |

0.021 |

0.021 |

0 ± 0.06 |

| C18:1 cis-15 |

Cis-15 Octadecenoic |

377 |

0.06 ± 0.002 |

0.0 |

0.0005 |

0.0005 |

0 ± 0.06 |

| C18:1 trans-6, 7, 8 |

Trans-6,7,8 Octadecenoic |

378 |

0.18 ± 0.004 |

0.0007 |

0.0055 |

0.0062 |

0.11 ± 0.09 |

| C18:1 trans-10, 11, 12 |

Trans-10,11,12 Octadecenoic |

378 |

1.07 ± 0.02 |

0.0236 |

0.0926 |

0.1162 |

0.20 ± 0.12 |

| C18:1 trans-16 |

Trans-16 Octadecenoic |

377 |

0.14 ± 0.003 |

0.0 |

0.0023 |

0.0023 |

0 ± 0.09 |

| C18:2 cis-9 cis-12 n-6 |

Linoleic acid |

377 |

1.60 ± 0.03 |

0.0340 |

0.239 |

0.273 |

0.12 ± 0.10 |

| C18:2 cis-9 trans-11 |

Vaccenic acid |

377 |

0.21 ± 0.003 |

0.0001 |

0.0026 |

0.0027 |

0.04 ± 0.09 |

| C18:2 trans-11 cis-15 |

Octadecenoic acid |

374 |

0.07 ± 0.001 |

0.00007 |

0.0004 |

0.00047 |

0.13 ± 0.11 |

| C18:3 n-6 |

α-Linolenic acid |

377 |

0.06 ± 0.001 |

0.00008 |

0.0002 |

0.00028 |

0.24 ± 0.13 |

| C18:3 n-3 |

γ-Linolenic acid |

376 |

0.16 ± 0.005 |

0.00026 |

0.0017 |

0.00196 |

0.13 ± 0.11 |

| C20:1 |

Eicosanoic acid |

374 |

0.11 ± 0.002 |

0.00013 |

0.0014 |

0.00153 |

0.09 ± 0.10 |

| C20:2 |

Eicosadienoic acid |

306 |

0.01 ± 0.0003 |

0.0 |

0.00004 |

0.00004 |

0 ± 0.08 |

| C20:3 n-6 |

Eicosatrienoic acid |

373 |

0.11 ± 0.003 |

0.00018 |

0.00235 |

0.00253 |

0.07 ± 0.09 |

| C20:4 n-6 |

Arachidonic acid |

377 |

0.36 ± 0.008 |

0.00221 |

0.0235 |

0.0251 |

0.09 ± 0.10 |

| C20:5 n-3 (EPA) |

Eicosapentaenoic acid |

376 |

0.08 ± 0.002 |

0.00005 |

0.00135 |

0.00139 |

0.04 ± 0.09 |

| C22:5 n-3 (DPA) |

Docosapentaenoic acid |

377 |

0.17 ± 0.003 |

0.00047 |

0.00387 |

0.00434 |

0.11 ± 0.10 |

| C22:6 n-3 (DHA) |

Docosahexaenoic acid |

364 |

0.03 ± 0.001 |

0.00003 |

0.00018 |

0.00021 |

0.13 ± 0.10 |

| SFA3 |

Sum of saturated FA |

377 |

47.23 ± 0.23 |

1.960 |

15.00 |

16.960 |

0.11 ± 0.09 |

| MUFA3 |

Sum of monounsaturated FA |

377 |

48.34 ± 0.23 |

2.367 |

14.963 |

17.33 |

0.14 ± 0.10 |

| PUFA3 |

Sum of polyunsaturated FA |

377 |

2.87 ± 0.04 |

0.097 |

0.547 |

0.644 |

0.15 ± 0.10 |

| n-34 |

Sum of omega-3 |

377 |

0.44 ± 0.09 |

0.00034 |

0.0016 |

0.00194 |

0.17 ± 0.11 |

| n-64 |

Sum of omega-6 |

377 |

2.13 ± 0.04 |

0.00055 |

0.0031 |

0.00365 |

0.15 ± 0.11 |

| PUFA:SFA |

Ratio of PUFA to SFA |

377 |

6.08 ± 0.003 |

0.0623 |

0.41 |

0.4723 |

0.13 ± 0.10 |

| n-6:n-3 |

Ratio of n-6 to n-3 |

377 |

4.84 ± 0.11 |

0.00395 |

0.0231 |

0.02705 |

0.14 ± 0.10 |

| AI5 | Atherogenic index | 377 | 0.82 ± 0.05 | 0.03943 | 1.0784 | 1.11783 | 0.03 ± 0.09 |

1IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology.

2SE Standard error.

3MUFA, PUFA and SFA were the total of all monounsaturated, polyunsaturated and saturated fatty acids, respectively.

4n-3 and n-6 were total of omega 3 and 6 fatty acids.

5Atherogenic index = [12:0 + 4(14:0) + 16:0]/(SFA + PUFA).

The omega 6: omega 3 (n-6:n-3) ratio was high (4.84), which has a beneficial effect on patients with chronic diseases. A ratio of 4:1 has been associated with a 70% decrease in total mortality in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease [24]. Omega 6 and 3 fatty acids are essential cell membrane and tissue constituents that are important for many biological functions. These fatty acids are also essential for synthesis of prostaglandins, thromboxane, leukotriene, hydroxyl fatty acids, and lipoxins that are involved with inflammatory response. Humans and other mammals can convert n-6 to n-3 using desaturation enzymes but this conversion is slow and there is competition between n-6 and n-3 fatty acids for the desaturation enzymes [25].

Heritability

Descriptive statistics and heritabilities estimated using a genomic relationship G matrix are in Table 1. Heritabilities estimated in this study varied from low (<0.10 for C12:0, C16:0, C18:1 cis-11, C18:1 cis-12, C18:2 cis-9 trans-11, C20:1, C20:3 n-6, C20:4 n-6, C20:5 n-3 and AI, respectively) to moderate (up to 0.29 for IMF, C14:0, C14:1 cis-9, C16:1 cis-9, C17:0, C17:1, C18:0, C18:1 cis-9, C18:1 trans-6, 7, 8, C18:1 trans-10, 11, 12, C18:2 cis 9 cis-12 n-6, C18:2 trans-11 cis-15, C18:3 n-6, C18:3 n-3, C22:5 n-3, C22:6 n-3, SFA, MUFA, PUFA, Sn-3, Sn-6 and n-6:n-3). For C15:0, C18:1 cis-13, C18:1 cis-15, C18:1 trans-16, C20:2 the heritability estimates were zero. In Angus [26] and Japanese Black cattle [27] estimates of heritability for IMF fat deposition and composition traits were higher than in this study. The lower values of heritability reported for this population could be explained by the reduced sample size [28] or lower amount of genetic variation in the population [29].

The estimates of genomic heritability from Bayes B approach (Table 2) were also low to moderate (from 0.09 to 0.46) and generally similar to values obtained in ASReml using a genomic relationship matrix.

Table 2.

Posterior means of variance components for IMF deposition and composition in Nellore by Bayes B

| Trait | Genetic variance | Residual variance | Total variance | Genomic heritability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMF (%) |

0.16 |

0.48 |

0.64 |

0.25 |

| C12:0 (mg/mg) |

0.0001 |

0.0006 |

0.0007 |

0.18 |

| C14:0 |

0.06 |

0.23 |

0.29 |

0.20 |

| C14:1 cis-9 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.25 |

| C15:0 |

0.006 |

0.04 |

0.046 |

0.12 |

| C16:0 |

2.42 |

5.47 |

7.89 |

0.31 |

| C16:1 cis-9 |

0.10 |

0.30 |

0.40 |

0.24 |

| C17:0 |

0.004 |

0.02 |

0.024 |

0.17 |

| C17:1 |

0.002 |

0.01 |

0.012 |

0.17 |

| C18:0 |

1.23 |

5.28 |

6.51 |

0.19 |

| C18:1 cis-9 |

6.08 |

7.11 |

13.19 |

0.46 |

| C18:1 cis-11 |

0.04 |

0.33 |

0.37 |

0.11 |

| C18:1 cis-12 |

0.005 |

0.03 |

0.035 |

0.13 |

| C18:1, cis-13 |

0.02 |

0.002 |

0.022 |

0.09 |

| C18:1 cis-15 |

0.0009 |

0.0004 |

0.00049 |

0.17 |

| C18:1 trans-6, 7, 8 |

0.0008 |

0.005 |

0.0058 |

0.13 |

| C18:1 trans-10, 11, 12 |

0.02 |

0.09 |

0.11 |

0.16 |

| C18:1 trans-6 |

0.0003 |

0.002 |

0.0023 |

0.16 |

| C18:2 cis 9 cis-12 n-6 |

0.03 |

0.23 |

0.26 |

0.13 |

| C18:2 cis9, trans-11 |

0.0003 |

0.002 |

0.0023 |

0.12 |

| C18:2 trans-11 cis-15 |

0.0001 |

0.0004 |

0.0005 |

0.22 |

| C18:3 n-6 |

0.00007 |

0.0003 |

0.00037 |

0.21 |

| C18:3 n-3 |

0.0003 |

0.002 |

0.0023 |

0.14 |

| C20:1 |

0.0002 |

0.001 |

0.0012 |

0.16 |

| C20:2 |

0.00005 |

0.00002 |

0.00007 |

0.22 |

| C20:3 n-6 |

0.0003 |

0.002 |

0.0023 |

0.14 |

| C20:4 n-6 |

0.002 |

0.02 |

0.022 |

0.08 |

| C20:5 n-3 |

0.0002 |

0.001 |

0.0012 |

0.17 |

| C22:5 n-3 |

0.0007 |

0.003 |

0.0037 |

0.16 |

| C22:6 n-3 |

0.00006 |

0.0002 |

0.00026 |

0.24 |

| SFA1 |

1.36 |

15.54 |

16.90 |

0.08 |

| MUFA1 |

1.67 |

15.18 |

16.85 |

0.10 |

| PUFA1 |

0.09 |

0.54 |

0.63 |

0.14 |

| n-32 |

0.004 |

0.013 |

0.017 |

0.25 |

| n-62 |

0.0005 |

0.003 |

0.0035 |

0.15 |

| PUFA:SFA |

0.003 |

0.02 |

0.023 |

0.11 |

| n-6:n-3 |

0.66 |

1.23 |

1.89 |

0.34 |

| AI3 | 0.007 | 0.03 | 0.037 | 0.16 |

1MUFA, PUFA and SFA were the total of all monounsaturated, polyunsaturated and saturated fatty acids, respectively.

2n-3 and n-6 were total of omega 3 and 6 fatty acids.

3Atherogenic index = [12:0 + 4(14:0) + 16:0]/(SFA + PUFA).

Genome wide association studies and genomic regions identified

GWAS and genomic regions identified were reported for those traits that showed genomic heritability ≥ 0.10: IMF, 33 different FA and ratios, and one FA index. The 1-Mb SNP window regions that explained more than 1% of the genetic variance were used to search for putative candidate genes (PCG) and are presented on Table 3. Therefore, 35 traits were used for GWAS and these represented 23 different 1-Mb genomic regions (Table 3). These regions were distributed over 12 different chromosomes: 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 17, 26 and 27 and the corresponding PCG in these regions are reported in Table 3. Intramuscular fat was one of the traits that presented moderate heritability (0.25), however no region that explained more than 1% of the genetic variance for this trait was identified.

Table 3.

QTL regions associated with fatty acid composition in Nellore steers by Bayes B

| Group | Traits | QTL window (first and last SNP) | Number of SNP /window 1 | %Variance explained SNP window 1 | Chr | Map position (UMD 3.1 bovine assembly) | PCG 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Saturated fatty acid |

C14:0 |

rs43328164 - rs134696015 |

295 |

1.06 |

3 |

6009105 - 6999643 |

-

3

|

| |

C18:0 |

rs133274959 - rs136576856 |

213 |

3.46 |

3 |

25008982 - 25990012 |

HMGCS2, PHGDH, HSD3B1, HAO2 |

| |

C16:0 |

rs134160160 - rs109942510 |

285 |

1.38 |

3 |

26002777 - 26998679 |

WARS2 |

| |

C14:0 |

rs41627556 - rs110731616 |

332 |

1.43 |

9 |

36013595 - 36997263 |

GNG11, RGS5 |

| |

C18:0 |

rs136405986 - rs137105475 |

114 |

1.08 |

10 |

74001100 - 74957582 |

DHRS7 |

| |

C18:0 |

rs132804279 - rs109645596 |

102 |

2.08 |

11 |

105009792 - 105985714 |

NUP214 |

| |

C16:0 |

rs109773631 - rs135618512 |

277 |

1.53 |

12 |

13000697 - 13997298 |

- |

| |

C12:0 |

rs42924061 - rs134942057 |

214 |

3.48 |

12 |

60000226 - 60994461 |

SLITRK6 |

|

Monounsat. fatty acid |

C14:1 cis-9 |

rs137683417 - rs29003360 |

232 |

1.86 |

2 |

26002605 - 26999718 |

GAD1, Sp5 |

| |

C18:1 cis-9 |

rs134160160 - rs109942510 |

285 |

1.40 |

3 |

26002777 - 26998679 |

WARS2 |

| |

C16:1 cis-9 |

rs133274959-rs136576856 |

213 |

1.42 |

3 |

25008982 - 25990012 |

HMGCS2, PHGDH, HSD3B1, HAO2 |

| |

C18:1 cis-9 |

rs133274959-rs136576856 |

213 |

2.57 |

3 |

25008982 - 25990012 |

HMGCS2, PHGDH, HSD3B1, HAO2 |

| |

C18:1 t-16 |

rs133728493 - rs109630757 |

264 |

2.56 |

6 |

50008629 - 50996673 |

- |

| |

C16:1cis-9 |

rs135892505 - rs109693564 |

184 |

1.04 |

7 |

80006438 - 80997126 |

- |

| |

C16:1cis-9 |

rs136405986 - rs137105475 |

114 |

1.18 |

10 |

74001100 - 74957582 |

DHRS7 |

| |

C14:1cis-9 |

rs110517663 - rs137137362 |

127 |

1.43 |

11 |

27000446 - 27993515 |

ABCG5 |

| |

C18:1 cis-9 |

rs109773631 - rs135618512 |

277 |

1.91 |

12 |

13000697 - 13997298 |

- |

| |

C14:1 cis-9 |

rs137754875 - rs135670282 |

203 |

1.55 |

12 |

66002783 - 66997356 |

GPC6 |

| |

C18:1 t-16 |

rs109872854 - rs134277482 |

250 |

2.17 |

17 |

41001273 - 41991683 |

RAPGEF2, RPS27 |

|

Polyunsat. fatty acid |

C22:5 n-3 |

rs132839318 - rs134264692 |

306 |

3.35 |

3 |

27001604 - 27997941 |

SPAG7, WDR3 |

| |

C18:2 t-11c-15 |

rs42404785 - rs133183089 |

144 |

1.69 |

3 |

72000121 - 72997801 |

AQP7, LOXL2 |

| |

C18:3 n-6 |

rs109612389 - rs133661384 |

205 |

1.34 |

7 |

34004443 - 34998434 |

- |

| |

C18:2 t-11c-15 |

rs135377389 - rs133297940 |

267 |

3.49 |

8 |

68013821 - 68993778 |

- |

| |

C22:5 n-3 |

rs110411459 - rs137802105 |

202 |

4.74 |

10 |

29000222 - 29962997 |

- |

| |

C20:5 n-3 |

rs137823965 - rs42507195 |

199 |

2.19 |

10 |

49005824 - 49980174 |

RORA |

| |

C18:3 n-3 |

rs42582725 - rs133775322 |

132 |

1.33 |

17 |

24002089 - 24987264 |

- |

| |

C18:2 t-11c-15 |

rs137602675 - rs133056879 |

187 |

1.01 |

26 |

20001875 - 20999270 |

- |

| |

C20:3 n-6 |

rs134302284 - rs136338106 |

144 |

1.77 |

27 |

26000833 - 26975692 |

- |

|

Total of MUFA |

MUFA |

rs133274959 - rs136576856 |

213 |

3.24 |

3 |

25008982 - 25990012 |

HMGCS2, PHGDH, HSD3B1, HAO2 |

| |

|

rs134160160 - rs109942510 |

285 |

1.13 |

3 |

26002777 - 26998679 |

WARS2 |

|

Total of n-3 |

n-3 |

rs110411459 - rs137802105 |

202 |

2.59 |

10 |

29000222 - 29962997 |

- |

| |

|

rs137823965 - rs42507195 |

199 |

2.25 |

10 |

49005824 - 49980174 |

- |

| |

|

rs1322839318 - rs134264692 |

306 |

1.37 |

3 |

27001604 - 27997941 |

SPAG7, WDR3 |

| Total of n-6 | n-6 | rs134302284 - rs136338106 | 144 | 2.47 | 27 | 26000833 - 26975692 | - |

11 Mb window.

2Positional candidate genes.

3No putative candidate gene associated with the trait.

Saturated fatty acids

Eight genomic regions (1 Mb windows) explained more than 1% of genotypic variation for C12:0, C14:0, C16:0, and C18:0 (Table 3). These regions overlap with QTL previously reported for marbling score [28], backfat thickness [29], carcass weight and body weight in Angus cattle [30]. Additional file 1 shows in more detail the Manhattan plot of the proportion of genetic variance explained by window across the 29 autosomes for the important saturated fatty acids for beef palatability: C12:0 (lauric acid), palmitic acid (C16:0), stearic acid (C18:0).

BTA12 at 60 Mb QTL region was associated with C12:0 fatty acid and harbors the PCG SLIT and NTRK-like family, member 6 (SLITRK6). This gene is related to the lipopolysaccharide receptor complex (GO:0016021). Lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin) is an important component of gram-negative cell walls, which can start the inflammatory process by binding to the SLITRK6 complex. This complex is located at the surface of innate immune cell, which presents an important role in obesity associated with insulin resistance [31].

BTA3 at 6 Mb and BTA9 at 36 Mb were associated with C14:0 fatty acid. In the first region, no PCG was identified. In the second region, the following PCGs were identified: guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), gamma 11 (GNG11) and regulator of G-protein signaling 5 (RGS5). These genes are associated with G proteins that have been implicated in the regulation of body weight and metabolic function, hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose tolerance and resistance to insulin in mice [32].

BTA3 at 26 Mb and BTA12 at 13 Mb were associated with C16:0 fatty acid. In the first QTL region the tryptophanyl tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (WARS2) gene was identified. In BTA12 at 13 Mb no PCG was identified. WARS2 gene encodes an essential enzyme that catalyzes aminoacylation of tRNA with tryptophan. The WARS2 protein contains a signal peptide for mitochondrial import, OMIM: 604733 [33], and is involved with regulation of fat distribution in human visceral and subcutaneous fat [34].

BTA3 at 25 Mb, BTA10 at 74 Mb and BTA11 at 105 Mb QTL regions were associated with C18:0 fatty acid. On BTA3 at 25 Mb four PCG were identified: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A synthase 2, mitochondrial (HMGCS2), phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), hydroxy-delta-5-steroid dehydrogenase, 3 beta- and steroid delta-isomerase 1 (HSD3B1) and hydroxyacid oxidase 2, long chain (HAO2). HMGCS2 was associated with fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis in HepG2 cells [35] and is directly regulated by PPAR-α gene that is an important key regulator of β-oxidation. On the other hand the PPAR-γ expression induces lipogenesis by PXR activation in mice liver [36]. PHGDH is related to the regulation of gene expression according to gene ontology (GO) terms (GO:0010468), HSD3B1 gene is associated with steroid biosynthesis (GO:0006694) and metabolic process (GO: 0008202) and HAO2 is associated with fatty acid oxidation (GO:0019395).

On BTA10 at 74 Mb QTL region, dehydrogenases/reductases (SDRs) (DHRS7) was identified. DHRS7 catalyzes the oxidation/reduction of a wide range of substrates, including retinoid and steroids [37] and has high expression level in adipocyte and skeletal muscle [38]. In addition, this gene is responsible for the final step in cholesterol production, the conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterol to cholesterol [39].

On BTA11 at 105 Mb region, NUP214 was identified. This gene is involved with intermembrane transport. The nucleoporins are characterized by phenylalanine-glycine rich (FG) repeat sequences and the FG domains have an unfolded structure and are responsible for interaction with importin-cargo complexes that move through the pore. One of these importin-cargo complexes is sterol regulatory element binding proteins-sterol-sensing accessory factor (SREBP-SCAP). This factor enters the nucleus, then binds to sterol regulatory elements (SRE) in the promoter regions of genes, whose products mediate the synthesis of cholesterol and fatty acids [40].

Monounsaturated fatty acids

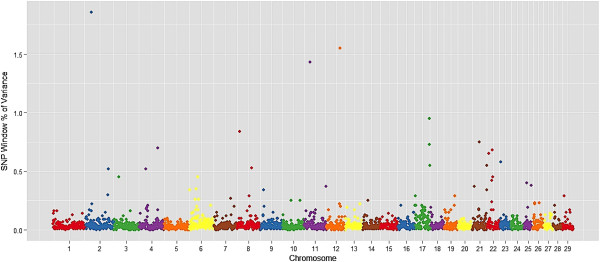

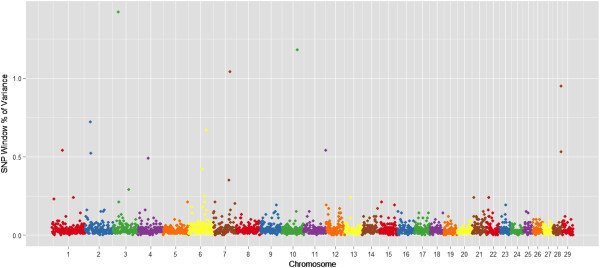

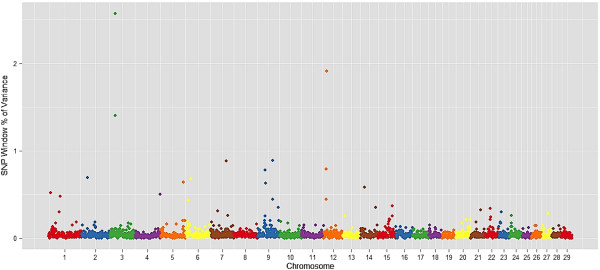

Ten genomic regions (1 Mb region) explained more than 1% of genotypic variation for monounsaturated fatty acids, which relates C14:1 cis-9, C16:1 cis-9, C18:1 cis-9, and C18:1 trans-16 (Table 3). These regions overlap with QTL reported for carcass weight, marbling score in Angus [30], docosahexaenoic acid content in Charolais x Holstein crossbred cattle [41] and palmitoleic acid in dairy cattle [42]. Manhattan plots of the proportion of genetic variance explained by each 1-Mb window (2,527 windows) across the 29 autosomes for the most important fatty acid for beef quality and human health: myristoleic acid (C14:1 cis-9), palmitoleic acid (C16:1 cis-9), and oleic acid (C18:1 cis-9) and are in Figures 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Figure 1.

Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association study for C14:1 cis 9 (myristoleic acid) in Nellore. The X-axis represents the chromosomes, and the Y-axis shows the proportion of genetic variance explained by SNP window from Bayes B analysis.

Figure 2.

Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association study result for C16:1 cis9 (palmitoleic acid) in Nellore. The X-axis represents the chromosomes, and the Y-axis shows the proportion of genetic variance explained by SNP window from Bayes B analysis.

Figure 3.

Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association study result for C18:1 cis9 (oleic acid) in Nellore. The X-axis represents the chromosomes, and the Y-axis shows the proportion of genetic variance explained by SNP window from Bayes B analysis.

BTA2 at 26 Mb, BTA11 at 27 Mb , and BTA12 at 66 Mb were associated with C14:1 cis-9 fatty acid. On BTA2 at 26 Mb region, glutamate decarboxylase 1 (GAD1) and specificity protein 5-transcription factor (Sp5) were identified. The GAD1 gene is involved with food behavior and insulin secretion. It was shown to be associated with morbid obesity [43] in humans, and body weight and daily gain in cattle [44]. Sp5 transcription factors are involved in the regulation of pyruvate kinase, lactate dehydrogenase and fatty acid synthase in cancer cells [45,46]. On BTA11 at 27 Mb region, ATP-binding cassete, sub-family G (WHITE), member 5 (ABCG5) was identified. The ABCG family members were associated with cellular lipid-trafficking in macrophages and hepatocytes. This gene also presents an important role in the PPARγ and LXR pathways [47]. On BTA12 at 66 Mb region, glypican 6 (GPC6) was identified. Glypicans family are involved with the control of cell growth and cell division. Other glypican gene, GPC4 was associated with body fat distribution and obesity in humans [48]. A previous GWAS using chicken population reported an association between GPC6 and body weigh, which has a stronger correlation with body fatness and obesity [49].

BTA3 at 25 Mb, BTA7 at 80 Mb and BTA10 at 74 Mb were associated with C16:1 cis-9 fatty acid. Both BTA3 at 25 Mb and BTA10 at 74 Mb regions were also associated with saturated fatty acids, where HMGCS2, PHGDH, HSD3B1, HAO2, and DHRS7 were described above. On BTA7 at 80 Mb region, no PCG associated with this trait was identified.

BTA3 at 25 Mb, BTA3 at 26 Mb, and BTA12 at 13 Mb were associated with C18:1 cis-9. The first two regions were also associated with saturated fatty acids (C18:0 and C16:0, respectively) and C16:1 cis-9. On BTA12 at 13 Mb region, there were no annotated genes [50].

BTA6 at 50 Mb and BTA17 at 41 Mb were associated with C18:1 trans-16. On BTA 6 at 50 Mb region, no PCG associated with this trait was identified, and on BTA17 at 41 Mb region one PCG was found: Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RAPGEF2), that selectively and non-covalently interacts with diacylglycerol, a diester of glycerol and two fatty acids (GO:0019992).

Four genomic regions were associated with saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids. BTA3 at 26 Mb and BTA12 at 13 Mb were associated with C16:0 and C18:1 cis-9. BTA3 at 25 Mb was associated with C18:0 and C18:1 cis-9. BTA3 at 25 and BTA10 at 74 Mb were associated with C18:0 and C16:1 cis-9. We also observed a negative phenotypic correlation between C16:0 and C18:1 (r = -0.65) and between C18:0 and C18:1(r = -0.72). Palmitic acid (C16:0) carbon chain skeleton is a predominant source for fatty acid elongation and desaturation, which might generate palmitoleic (C16:1 cis-9), stearic (C18:0), and oleic (C18:1 cis-9) fatty acids [51]. Examination of the 30 markers with the larger effect in regions of BTA3 at 26 Mb and BTA12 at 13 Mb (Table 4) and BTA3 at 25 Mb (Additional file 2) revealed that alleles positively associated with saturated fatty acid were negatively associated with unsaturated fatty acids. This indicates that QTL in these regions are directly or indirectly involved with elongation and/or desaturation.

Table 4.

Top 30 markers effect in BTA3 at 26 Mb and BTA12 at 13 Mb QTL associated with C16:0 and C18:1 cis-9 in Nellore steers

|

BTA3 at 26 Mb |

BTA12 at 13 Mb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP name | Marker effect C16:0 | Marker effect 18:1 cis-9 | Position (Chr_Bp) | SNP name | Marker effect C16:0 | Marker effect 18:1 cis-9 | Position (Chr_bp) |

| rs136571109 |

1.49E-02 |

-8.42E-03 |

3_26426591 |

rs109310464 |

1.53E-02 |

-3.10E-02 |

12_13152910 |

| rs110996601 |

1.45E-02 |

-6.58E-03 |

3_26425542 |

rs137546638 |

1.97E-03 |

-6.73E-03 |

12_13172924 |

| rs134173038 |

1.40E-02 |

-6.05E-03 |

3_26427414 |

rs110182797 |

1.01E-03 |

-7.53E-04 |

12_13254936 |

| rs137302352 |

4.10E-03 |

-2.29E-03 |

3_26400703 |

rs110951319 |

6.73E-04 |

-4.73E-04 |

12_13257070 |

| rs135909241 |

9.74E-04 |

-2.55E-04 |

3_26446293 |

rs109014250 |

5.98E-04 |

-6.22E-04 |

12_13687406 |

| rs109610305 |

7.91E-04 |

-1.72E-05 |

3_26497009 |

rs137052772 |

5.83E-04 |

-3.95E-04 |

12_13343491 |

| rs137775131 |

5.12E-04 |

-7.50E-05 |

3_26501617 |

rs42625291 |

5.42E-04 |

-1.25E-03 |

12_13689345 |

| rs109564367 |

5.01E-04 |

-8.52E-03 |

3_26073307 |

rs132782691 |

5.23E-04 |

-1.87E-04 |

12_13334837 |

| rs110447932 |

4.30E-04 |

-8.35E-03 |

3_26072388 |

rs110645603 |

2.15E-04 |

-6.03E-05 |

12_13226418 |

| rs109719131 |

3.84E-04 |

-9.90E-05 |

3_26465447 |

rs135746294 |

1.74E-04 |

-2.71E-05 |

12_13037523 |

| rs110569793 |

3.62E-04 |

-9.64E-05 |

3_26476929 |

rs109497621 |

1.16E-04 |

-5.02E-05 |

12_13679288 |

| rs133474163 |

3.39E-04 |

-1.56E-02 |

3_26143362 |

rs42625298 |

1.13E-04 |

-1.40E-04 |

12_13703328 |

| rs110930607 |

3.22E-04 |

-1.90E-04 |

3_26332392 |

rs133583231 |

1.09E-04 |

-5.69E-05 |

12_13557660 |

| rs134881809 |

3.10E-04 |

-2.36E-04 |

3_26505695 |

rs110721694 |

1.01E-04 |

-2.78E-03 |

12_13696926 |

| rs111020805 |

2.70E-04 |

-1.92E-03 |

3_26108986 |

rs135841134 |

9.62E-05 |

-4.91E-05 |

12_13897680 |

| rs134887465 |

2.68E-04 |

-2.04E-04 |

3_26385596 |

rs41667835 |

9.59E-05 |

-1.41E-04 |

12_13710147 |

| rs110953593 |

2.61E-04 |

-8.47E-03 |

3_26075185 |

rs136432856 |

9.51E-05 |

3.08E-05 |

12_13493245 |

| rs109658959 |

2.57E-04 |

-7.53E-03 |

3_26596824 |

rs133513235 |

9.45E-05 |

-4.21E-04 |

12_13251749 |

| rs136570164 |

2.56E-04 |

-7.23E-05 |

3_26961906 |

rs137549822 |

8.60E-05 |

-6.65E-04 |

12_13081160 |

| rs132696738 |

2.51E-04 |

-2.80E-04 |

3_26338744 |

rs110015470 |

8.45E-05 |

-3.18E-04 |

12_13682141 |

| rs134559574 |

2.46E-04 |

-3.01E-05 |

3_26774155 |

rs133443666 |

8.30E-05 |

-1.46E-04 |

12_13520963 |

| rs133573311 |

2.20E-04 |

-1.54E-04 |

3_26330114 |

rs208626835 |

8.10E-05 |

5.29E-06 |

12_13515819 |

| rs135402139 |

1.94E-04 |

-1.26E-04 |

3_26954008 |

rs134142865 |

7.61E-05 |

-2.40E-04 |

12_13264826 |

| rs135422840 |

1.71E-04 |

-3.00E-03 |

3_26020004 |

rs134240141 |

7.39E-05 |

-7.90E-05 |

12_13571494 |

| rs136944072 |

1.66E-04 |

-2.63E-03 |

3_26149734 |

rs110659649 |

6.83E-05 |

-3.57E-05 |

12_13092209 |

| rs110497471 |

1.56E-04 |

-2.50E-04 |

3_26576223 |

rs135136417 |

6.58E-05 |

-3.14E-05 |

12_13266029 |

| rs137361087 |

1.45E-04 |

-3.15E-03 |

3_26144230 |

rs109064784 |

6.32E-05 |

-8.96E-05 |

12_13785143 |

| rs110049045 |

1.37E-04 |

-7.04E-05 |

3_26975095 |

rs135831828 |

6.31E-05 |

-3.94E-05 |

12_13769919 |

| rs133610187 |

1.36E-04 |

-2.31E-04 |

3_26290060 |

rs135423477 |

6.25E-05 |

-1.43E-04 |

12_13642422 |

| rs110819650 | 1.35E-04 | -4.69E-05 | 3_26979811 | rs109147565 | 6.16E-05 | -1.53E-03 | 12_13097096 |

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

Nine genomic regions (1 Mb window) explained > 1% of genotypic variation for group of polyunsaturated fatty acids, which relates C18:2 cis-9 cis12 n-6, C18:2 trans-11 cis-15, C18:3 n-3, C18:3 n-6, C20:3 n-6, C20:5 n-3, and C22:5 n-3 (Table 3). These overlapped with QTL reported for marbling score, body weight in Angus cattle [30], intramuscular fat, saturated fatty acid content, stearic acid in Fleckvieh bulls [52] and RFI in half-sib families from Angus and Charolais [53]. Additional file 3 shows in more detail the Manhattan plot of the proportion of genetic variance explained by window across the 29 autosomes for the important fatty acid to human health: γ-linolenic acid (C18:3 n-3), α-linolenic acid (C18:3 n-6) and total of n-3 (n-3).

BTA3 at 72 Mb, BTA 8 at 68 Mb, and BTA26 at 20 Mb were associated with C18:2 trans-11 cis-15 fatty acid. On BTA3 at 72 Mb QTL region, two PCG related to lipid metabolism were observed: aquaporin 7 (AQP7) and lysil oxidase-like2 (LOXL2). AQP7 is involved with the PPAR signaling pathway [54], while LOXL2 is associated with lean body mass in mouse [55]. On BTA 8 at 68 Mb and BTA26 at 20 Mb no PCG was associated with this trait.

BTA10 at 49 Mb region was associated with C20:5 n-3 fatty acid, which harbors the RAR-related orphan receptor A (RORA) gene that is related to steroid hormone receptor activity. When combined with a steroid hormone, it produces the signal within the cell to initiate a change in cell activity or function (GO:0003707).

BTA3 at 27 Mb and BTA10 at 29 Mb QTL regions explained more than 1% of genetic variance for C22:3 n-3. The first region (BTA3 at 27 Mb) harbors two PCG: SPAG17 and WDR3. These genes are involved with nucleus membrane (cellular components), the lipid bilayers that surround the nucleus and that form the nuclear envelope excluding the intermembrane space (GO:0031965). In the second region no PCG involved with this trait was identified. In other regions associated with C18:3 n-3 (BTA7 at 34 Mb), C18:3 n-6 (BTA17 at 24 Mb), and C20:3 n-6 (BTA27 at 26 Mb) no annotated genes were found [56].

The total of omega-3 (n-3) and omega-6 (n-6) GWAS result is consistent with individual polyunsaturated n-3 and n-6 fatty acids, where the same QTL regions were associated with these traits (BTA3 at 27 Mb and BTA 27 at 26 Mb).

GWAS have been used to investigate complex traits in many species including livestock [6]. Deposition and composition of fat in mammalians are complex traits and are influenced by many loci throughout the genome [57]. GWAS provides one approach to understand the genetic variation in complex traits, by identifying regions that can be fine-mapped to identify individual loci responsible for variation [58]. In the present GWAS two interesting QTL regions BTA3 at 25 Mb and BTA3 at 26 Mb were associated with saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids in Bos indicus cattle. These regions harbor interesting PCG, which are involved with lipid metabolism in different species.

Previous studies reported CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBPβ), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ or PPARG), carnitine palmitoyltransferase–1 beta (CPT–1β), stearoylcoenzyme A desaturase (SCD), AMP-activated protein kinase alpha (AMPKα), and G-coupled protein receptor 43 (GPR43) genes to be related to fat deposition and fatty acid composition in Angus [59]. In this GWAS and in a recent GWAS publication using Angus cattle, the regions that harbor these genes were not associated with fat deposition and fatty acid composition [60]. However, the positional candidate genes HMGCS2, PHGDH, HSD3B1 and HAO2 identified in the present study are involved in the PPAR signaling pathway in human (PATH: hsa03320), carbon metabolism (PATH:bta01200), lipid metabolism and steroid hormone biosynthesis (PATH: bta00140), carbohydrate metabolism and glycosylate and decarboxylase metabolism (PATH: bta00630) according to Kegg: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes [61], respectively.

This is the first GWAS for intramuscular fat deposition and composition in Nellore. GWAS results in Bos taurus (Angus and Japanese Black cattle) reported different genomic regions associated with fat deposition and composition than those reported herein [62,63]. Previously, it has been reported that a QTL on BTA19 was associated with fatty acid composition in Bos taurus breeds. This region on BTA19 harbors fatty acid synthase gene (FASN), which is an enzyme involved with de novo synthesis of long-chain fatty acid in mammalian, lipogenesis. FASN has been suggested as a candidate gene for fat traits in beef cattle [60,62,63].

Differences in SNP allele frequencies and linkage disequilibrium profile (LD between SNPs and causal variants) may explain the different marker effects between Bos indicus and Bos taurus cattle [64,65]. This explanation has been confirmed by Bolormaa and collaborators [66], who compared marker effects using GWAS for Bos taurus and Bos indicus animals, which demonstrated that a SNP effect depends on the origin of alleles and the QTL segregation. The QTL segregation could result from mutation lost or fixation of alleles in one of the breeds, and also that the mutations occurred after divergence of these breeds [67]. Furthermore, it is possible that the differences in physiological and metabolism factors could contribute to the observed differences between different breeds [12].

Conclusion

The present study using BovineHD BeadChip (770 k) identified several 1-Mb SNP regions and genes within these regions that were associated with IMF and FA. The values of genomic heritabilities described in this study have not been reported before for Nellore cattle, and this information is important for breeding programs interesting in improving these traits. IMF deposition and composition are considered complex traits (polygenic) and are moderately heritable. In this study it is apparent that IMF composition are affected by many loci with small effects. Identification of several genomic regions and putative positional genes associated with lipid metabolism reported here should contribute to the knowledge of the genetic basis of IMF and FA deposition and composition in Nellore cattle (Bos indicus breed) and lead to selection for those traits to improve human nutrition and health.

Methods

Animals were handled and managed according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee Guidelines from Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation – EMBRAPA approved by the president, Dr. Rui Machado.

Animals and phenotypes

Nellore steers (386) bred in the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA/Brazil) experimental breeding herd between 2009 and 2011 were available for this study. Steers were sired by 34 unrelated sires, and were selected to represent the main genealogies used in Brazil according to the National Summary of Nellore produced by the Brazilian Association of Zebu Breeders (ABCZ) and National Research Center for Beef Cattle. Animals were raised in feedlots under identical nutrition and handling conditions until slaughter at an average age of 25 months [68]. Steaks (2.54 cm thick) from the Longissimus dorsi muscle between the 12th and 13th ribs were collected 24 hours after slaughter.

Muscle samples (~100 g) were lyophilized and ground for IMF and FA analysis. The IMF was obtained using an Ankom XT20 extractor as described [69]. FA analysis was conducted as described by Hara and Radin [70], except the hexane to propanol ratio was increased to 3:2. Approximately 4 g of LD muscle was lyophilized, ground in liquid nitrogen, mixed with 28 mL of hexane/propanol (3:2 vol/vol) and homogenized for 1 min. Samples were vacuum filtered and 12 ml sodium sulfate (67 mg mL− 1) solution was added and agitated for 30 s. The supernatant was transferred to a tube with 2 g of sodium sulfate and insufflated with N2, after which the tube was sealed and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the liquid was transferred to 10 mL test tube, insufflated with N2, sealed and kept at − 20°C until dry with N2 for methylation. The extracted lipids were hydrolyzed and methylated as described by Christie [71], except that hexane and methyl acetate were used instead of hexane:diethyl ether:formic acid (90:10:1). Around 40 mg of lipids were transferred to a tube containing 2 mL of hexane. Subsequently, 40 μL of methyl acetate were added, the sample agitated, and 40 μL of methylation solution (1.75 mL of methanol/0.4 mL of 5.4 mol/L of sodium metoxyde) were added. This mixture was agitated for 2 min and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Then 60 μL of finishing solution (1 g of oxalic acid/30 mL of diethyl ether) were added and the mixture was agitated for 30 s, after which 200 mg of calcium chloride was added. The sample was then mixed and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Samples were centrifuged at 3200 rpm, for 5 min at 5°C. The supernatant was collected for determination of fatty acids. Fatty acid methyl esters were quantified with a gas chromatograph (ThermoFinnigan, Termo Electron Corp., MA, USA) equipped with a flame ionization detector and a 100 m Supelco SP-2560 (Supelco Inc., PA, USA) fused silica capillary column (100 m, 0.25 mm and 0.2 μm film thickness). The column oven temperature was held at 70°C for 4 min, then increased to 170°C at a rate of 13°C min−1, and subsequently increased to 250°C at a rate of 35°C min−1, and held at 250°C for 5 min. The gas fluxes were 1.8 mL min−1 for carrier gas (He), 45 mL min−1 for make-up gas (N2), 40 mL min−1 for hydrogen, and 450 mL min−1 for synthetic flame gas. One μL sample was analyzed. Injector and detector temperatures were 250 and 300°C, respectively. Fatty acids were identified by comparison of retention time of methyl esters of the samples with standards of fatty acids butter reference BCR-CRM 164, Anhydrous Milk Fat-Producer (BCR Institute for Materials and Reference Measurements) and also with commercial standard for 37 fatty acids Supelco TM Component FAME Mix (cat 18919, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA). The nomenclature of fatty acids follow IUPAC Compendium [72]. Fatty acids were quantified by normalizing the area under the curve of methyl esters using Chromquest 4.1 software (Thermo Electron, Italy). Fatty acids were expressed as a weight percentage (mg/mg). These analyses were performed at the Animal Nutrition and Growth Laboratory at ESALQ, Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil.

DNA extraction and genotypic data

DNA was isolated from blood as described by Tizioto et al. [68]. Genotyping was performed at the Bovine Functional Genomics Laboratory ARS/USDA and Genomics Center at ESALQ, Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil using BovineHD 770 k BeadChip (Infinium BeadChip, Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Genotypes were obtained in Illumina A/B allele format and used to represent a covariate value at each locus coded as 0, 1, or 2, representing the number of B alleles. Missing genotypes, represented < 0.2% of genotypes and were replaced with the average covariate value at that locus. Initial visualization and data analysis was performed by GenomeStudio Data Analysis Software [73]. The SNPs with call rate ≤ 95%, minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 5%, those located on sex chromosomes and those not mapped in the Bos taurus UMD 3.1 assembly were removed. After filtering, a total of 449,363 SNP were utilized in GWAS.

Descriptive statistics and heritability

Descriptive statistics for IMF and FA were estimated using PROC MEANS and normality tests were performed using PROC UNIVARIATE in SAS (Ver. 9.3; SAS Inst. Cary, NC). SAS PROC MIXED was used to test independent sources for significance. Fixed effects included contemporary group classes (animals with the same origin, birth year and slaughter date) and hot carcass weight as a covariate. Animal and residuals were fitted as random effects. Restricted maximum likelihood was used to estimate animal and residual variance components, heritability and standard error (SE) using ASREML software [74]. The model used in single-trait analyses of all traits was, y = Xb + Zu + e, where y is the vector of observations representing the trait of interest (dependent variable), X and Z are the design or incidence matrices for the vectors of fixed and random effects in b and u, respectively, and e was the vector of random residuals. The variance of vector u was Gσ2m for the genomic analyses where G is the genomic relationship matrix derived from SNP markers using allele frequencies as suggested by VanRaden [75], with σ2m being the marker-based additive genetic variance.

Genome wide association study

Associations between SNP and phenotypes (IMF and FA) were obtained using Bayes B, which analyzed all SNP data simultaneously and assumed a different genetic variance for each SNP locus [76,77]. The prior genetic and residual variances were estimated using Bayes C [78], with π being 0.9997. The model equation was:

where y was the vector of the phenotypic values, X was the incidence matrix for fixed effects, b was the vector of fixed effects defined above, k was the number of SNP loci (449,363), aj was the column vector representing the SNP covariate at locus j coded as the number of B alleles, βj was the random substitution effect for locus j, which conditional on σ2β was assumed to be normally distributed N (0, σ2β ) when δj= 1 but βj= 0 when δj= 0, with δj being a random 0/1 variable indicating the absence (with probability π) or presence (with probability 1-π) of locus j in the model, and e was the vector of the random residual effects assumed normally distributed N (0, σ2e ). The variance σ2β (or σ2e) was a priori assumed to follow a scaled inverse Chi-square with vβ= 4 (or ve= 10) degrees of freedom and scale parameter S2β (or S2e). The scale parameter for markers was derived as a function of the assumed known genetic variance of the population, based on the average SNP allele frequency and number of SNP assumed to have nonzero effects based on parameter π being 0.9997. This procedure used GenSel software [8] to obtain the posterior distributions of SNP effects using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). This comprised a burn-in period of 1,000 iterations from which results were discarded, followed by 40,000 iterations from which results were accumulated to obtain the posterior mean effect of each SNP. In the Bayesian variable selection multiple-regression models with π = 0.9997 about 100-150 SNP markers were fitted simultaneously in each MCMC iteration. Inference of associations in these multiple-regression models was based on 1-Mb genomic windows rather than on single markers [8,79]. Genomic windows were constructed from the chromosome and base-pair positions denoted in the marker map file [8] based on UMD3.1 bovine assembly.

The SNP effects from every 40th post burn in iteration were used to obtain samples from the posterior distribution of the proportion of variance accounted for by each window from 1,000 MCMC samples of genomic merit for each animal following Onteru et al. [79] and Peters et al. [7]. In the present study there were 2,527 1 Mb SNP windows across the 29 autosomes. The proportion of genetic variance explained by each window in any particular iteration was obtained by dividing the variance of window BV by the variance of whole genome BV in that iteration. The window BV was computed by multiplying the number of alleles that represent the SNP covariates for each consecutive SNP in a window by their sampled substitution effects in that iteration.

All traits were used for GWAS (Additional file 4) and genomic heritability estimate, but only the ones with genomic heritability ≥ 0.10 were reported. Fatty acids were indexed as groups of saturated, monounsaturated, polyunsaturated fatty acid, total of saturated fatty acid (SFA), total monounsaturated (MUFA), total of polyunsaturated (PUFA), total of omega 3 (n-3) and total of omega 6 (n-6). Genome windows with the highest posterior mean proportion of genetic variance ≥1% were considered the most important regions associated with the traits, and were declared the most promising QTL regions.

Positional candidate genes were investigated for 1 Mb windows using the Cattle Genome Browser [50] and UCSC Genome Browser [80], which allowed visualization of SNP based on Bos taurus genome assembly UMD 3.1. Animal QTL database (Animal QTLdb) was used to search for published QTL and trait mapping data [56]. Gene annotations were retrieved from Ensembl Genes 71 Database using Biomart software [54,81]. The functional classification of genes was done using DAVID [54] and BioGPS [38] online annotation databases. Those genes reported to be involved in fatty acid and lipid metabolism were selected as positional candidate genes.

Availability of supporting data

The data sets supporting the results of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Abbreviations

IMF: Intramuscular fat; LDL: Low density lipoprotein; MUFA: Total of monounsaturated fatty acid; FA: Fatty acid; SNP: Single nucleotide polymorphism; GWAS: Genome-wide association study; QTL: Quantitative trait loci; SFA: Saturated fatty acid; PUFA: Total of polyunsaturated fatty acid; CLA: Conjugated linoleic acid; PCG: Putative candidate gene; GO: Gene ontology; MAF: Minor allele frequency; SE: Standard error; MCMC: Markov chain Monte Carlo; SFA: Total of saturated fatty acid; n-3: Total of omega 3; n-6: Total of omega 6.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ASMC, LCAR, LLC, RRT, GBM, DPDL, RTN and MMA conceived and designed the experiment; ASMC, LCAR, LLC, RTN, RRT, MLN, ASC and TSS performed the experiments; ASMC, LCAR, MAM, PSNO, DJG, JMR and LLC did analysis and interpretation of results; ASMC, LCAR, DJG, JMR and LLC drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association study result for A) C12:0 (lauric acid) B) C16:0 (palmitic acid) C) C18:0 (stearic acid) in Nellore. The X-axis represents the chromosomes, and the Y-axis shows the proportion of genetic variance explained by SNP window from Bayes B analysis.

Top 30 markers effect in BTA3 at 25 Mb associated with C18:0 and C18:1 cis-9 in Nellore steers.

Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association study result for A) C18:3 n-3 (α-linolenic acid) B) C18:3 n-6 (α-linolenic acid) C) n-3 (total of n-3) in Nellore. The X-axis represents the chromosomes, and the Y-axis shows the proportion of genetic variance explained by SNP window from Bayes B analysis.

Top three QTL regions associated with IMF deposition and composition traits in Nellore by Bayes B.

Contributor Information

Aline SM Cesar, Email: alinecesar@usp.br.

Luciana CA Regitano, Email: luciana.regitano@embrapa.br.

Gerson B Mourão, Email: gbmourao@usp.br.

Rymer R Tullio, Email: rymer.tullio@embrapa.br.

Dante PD Lanna, Email: dplanna@usp.br.

Renata T Nassu, Email: renata.nassu@embrapa.br.

Maurício A Mudado, Email: mauricio.mudadu@embrapa.br.

Priscila SN Oliveira, Email: priscilaoliveira_zoo@yahoo.com.br.

Michele L do Nascimento, Email: mlnascime@gmail.com.

Amália S Chaves, Email: amaliasat@usp.br.

Maurício M Alencar, Email: mauricio@cppse.embrapa.br.

Tad S Sonstegard, Email: tad.sonstegard@ars.usda.gov.

Dorian J Garrick, Email: dorian@iastate.edu.

James M Reecy, Email: jreecy@iastate.edu.

Luiz L Coutinho, Email: llcoutinho@usp.br.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with funding from EMBRAPA (Macroprograma 1, 01/2005) and FAPESP (process number 2011/00005-7 and 2012/02383-1). LR, MA, GBM and LC were granted CNPq fellowships. The authors would like to acknowledge the collaborative efforts among EMBRAPA, University of São Paulo, Iowa State University and USDA ARS Bovine Functional Genomics Laboratory, and fruitful discussions with Madhi Saatchi, Xiaochen Sun and Anna Wolc.

References

- Laborde FL, Mandell IB, Tosh JJ, Wilton JW, Buchanan-Smith JG. Breed effects on growth performance, carcass characteristics, fatty acid composition, and palatability attributes in finishing steers. J Anim Sci. 2001;79(2):355–365. doi: 10.2527/2001.792355x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill S, van Elswyk ME. Meat Sci. Vol. 92. England: 2012 Elsevier Ltd; 2012. Red meat in global nutrition; pp. 166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsen MU, Overvad K, Dyerberg J, Heitmann BL. Intake of ruminant trans fatty acids and risk of coronary heart disease. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(1):173–182. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rule DC, MacNeil MD, Short RE. Influence of sire growth potential, time on feed, and growing-finishing strategy on cholesterol and fatty acids of the ground carcass and longissimus muscle of beef steers. J Anim Sci. 1997;75(6):1525–1533. doi: 10.2527/1997.7561525x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matukumalli LK, Lawley CT, Schnabel RD, Taylor JF, Allan MF, Heaton MP, O’Connell J, Moore SS, Smith TP, Sonstegard TS, Van Tassel CP. Development and characterization of a high density SNP genotyping assay for cattle. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes BJ, Bowman PJ, Chamberlain AC, Verbyla K, Goddard ME. Accuracy of genomic breeding values in multi-breed dairy cattle populations. Genet Sel Evol. 2009;41:51. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-41-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SO, Kizilkaya K, Garrick DJ, Fernando RL, Reecy JM, Weaber RL, Silver GA, Thomas MG. Bayesian genome-wide association analysis of growth and yearling ultrasound measures of carcass traits in Brangus heifers. J Anim Sci. 2012;90(10):3398–3409. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrick DJ, Fernando RL. Implementing a QTL detection study (GWAS) using genomic prediction methodology. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1019:275–298. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-447-0_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizilkaya K, Tait RG, Garrick DJ, Fernando RL, Reecy JM. Genome-wide association study of Infectious Bovine Keratoconjunctivitis in Angus cattle. BMC Genet. 2013;14:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash A, Stigler M. FAO Statistical Yearbook 2012: WORLD FOOD AND AGRICULTURE. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Picard B, Lefaucheur L, Berri C, Duclos MJ. Muscle fibre ontogenesis in farm animal species. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2002;42(5):415–431. doi: 10.1051/rnd:2002035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert SA, Reverter A, Byrne KA, Wang Y, Nattrass GS, Hudson NJ, Greenwood PL. Gene expression studies of developing bovine longissimus muscle from two different beef cattle breeds. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte MS, Paulino PV, Das AK, Wei S, Serao NV, Fu X, Harris SM, Dodson MV, Du M. Enhancement of adipogenesis and fibrogenesis in skeletal muscle of Wagyu compared with Angus cattle. J Anim Sci. 2013;91(6):2938–2946. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M, Wang X, Das AK, Yang Q, Duarte MS, Dodson MV, Zhu M. Manipulating mesenchymal progenitor cell differentiaton to optimize performance and carcass value of beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2013;91(3):1419–1427. doi: 10.2527/jas.2012-5670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huerta-Leidenz NO, Cross HR, Savell JW, Lunt DK, Baker JF, Smith SB. Fatty acid composition of subcutaneous adipose tissue from male calves at different stages of growth. J Anim Sci. 1996;74(6):1256–1264. doi: 10.2527/1996.7461256x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway JW, Savell JW, Hamby PL, Baker JF, Stouffer JR. Relationships of empty-body composition and fat distribution to live animal and carcass measurements in Bos indicus-Bos taurus crossbred cows. J Anim Sci. 1990;68(7):1818–1826. doi: 10.2527/1990.6871818x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles DD, Johnson ER. Breed differences in amount and distribution of bovine carcass dissectable fat. J Anim Sci. 1976;42:332. [Google Scholar]

- Nuernberg K, Dannenberger D, Nuernberg G, Ender K, Voigt J, Scollan ND, Wood JD, Nute GR, Richardson RI. Effect of grass-based and a concentrate feeding system on meat quality characteristics and fatty acid composition of longissimus muscle in different cattle breeds. Livest Prod Sci. 2005;94:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.livprodsci.2004.11.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padre R, Aricetti JA, Moreira FB, Mizubuti IY, Do Prado IN, Visentainer JV, de Souza NE, Matsushita M. Fatty acid profile, and chemical composition of Longissimus muscle of bovine steers and bulls finished in pasture system. Meat Sci. 2006;74(2):242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan MC, Rossato LV, Rodrigues EC, Alves SP, Bessa RJ, Ramos EM, Gama LT. Genotype x environment interactions for fatty acid profiles in Bos indicus and Bos taurus finished on pasture or grain. J Anim Sci. 2011;89(1):221–232. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado IN, Moreira FB, Matsushita M, de Souza NE. Longissimus dorsi fatty acids composition of Bos indicus and Bos indicus x Bos taurus crossbred steers finished in pasture. Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2003;46(4):601–608. [Google Scholar]

- USDA. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 23 (SR 23) [database on the Internet] Washington, DC: USDA, Agricultural Research Service; 2010. Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/SP2UserFiles/Place/12354500/Data/SR23/sr23_doc.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz M, Matsushita M, Visentainer J, Hernandez J, Ribeiro E, Shimokomaki M, Reeves J, Souza N. Proximate chemical composition and fatty acid profiles of Longissimus thoracis from pasture fed LHRH immunocastrated, castrated and intact Bos indicus bulls. S Afr J Anim Sci. 2005;35(1):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Simopoulos AP. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother. 2002;56(8):365–379. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00253-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simopoulos AP. The omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio, genetic variation, and cardiovascular disease. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17(Suppl 1):131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait R Jr, Zhang S, Knight T, Minick Bormann J, Beitz D, RJ M. Heritability estimates for fatty acid quantity in Angus beef. J Anim Sci. 2007;85(Suppl. 2):58. Abstr. [Google Scholar]

- Nogi T, Honda T, Mukai F, Okagaki T, Oyama K. Heritabilities and genetic correlations of fatty acid compositions in longissimus muscle lipid with carcass traits in Japanese Black cattle. J Anim Sci. 2011;89(3):615–621. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas E, Stone RT, Keele JW, Shackelford SD, Kappes SM, Koohmaraie M. A comprehensive search for quantitative trait loci affecting growth and carcass composition of cattle segregating alternative forms of the myostatin gene. J Anim Sci. 2001;79(4):854–860. doi: 10.2527/2001.794854x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas E, Shackelford SD, Keele JW, Koohmaraie M, Smith TP, Stone RT. Detection of quantitative trait loci for growth and carcass composition in cattle. J Anim Sci. 2003;81(12):2976–2983. doi: 10.2527/2003.81122976x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure MC, Morsci NS, Schnabel RD, Kim JW, Yao P, Rolf MM, McKay SD, Gregg SJ, Chapple RH, Northcutt SL, Taylor JF. Anim Genet. Vol. 41. England: 2010 The Authors, Animal Genetics 2010 Stichting International Foundation for Animal Genetics; 2010. A genome scan for quantitative trait loci influencing carcass, post-natal growth and reproductive traits in commercial Angus cattle; pp. 597–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, Flier JS. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(11):3015–3025. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W, Wang X, Xiao J, Chen K, Zhou H, Shen D, Li HT, Qizhu. Loss of Regulator of G Protein Signaling 5 Exacerbates Obesity, Hepatic Steatosis. Inflamm Insulin Resist. 2012;7(1):e30256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKusick VA. Mendelian Inheritance in Man and its online version, OMIM. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(4):588–604. doi: 10.1086/514346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleinitz D, Kloting N, Lindgren CM, Breitfeld J, Dietrich A, Schon MR, Lohmann T, Dressler M, Stumvoll M, McCarthy MI, Blüher M, Kovacs P. Fat depot-specific mRNA expression of novel loci associated with waist-hip ratio. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38(1):120–125. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Brau A, de Sousa-Coelho AL, Mayordomo C, Haro D, Marrero PF. Human HMGCS2 regulates mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and FGF21 expression in HepG2 cell line. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(23):20423–20430. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada T, Gao J, Xie W. PXR and CAR in energy metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(6):273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Palczewski K. Short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases in retina. Methods Enzymol. 2000;316:372–383. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)16736-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Orozco C, Boyer J, Leglise M, Goodale J, Batalov S, Hodge CL, Haase J, Janes J, Huss JW 3rd, Su AI. BioGPS: an extensible and customizable portal for querying and organizing gene annotation resources. Genome Biol. 2009;10(11):R130. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-11-r130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter FD. Mol Genet Metab. Vol. 71. United States: 2000 Academic Press; 2000. RSH/Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: a multiple congenital anomaly/mental retardation syndrome due to an inborn error of cholesterol biosynthesis; pp. 163–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Li S, Zhong W, Vihervaara T, Beaslas O, Perttila J, Luo W, Jiang Y, Lehto M, Olkkonen VM, Yan D. OSBP-related protein 8 (ORP8) regulates plasma and liver tissue lipid levels and interacts with the nucleoporin Nup62. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Gil B, Williams JL, Homer D, Burton D, Haley CS, Wiener P. Search for quantitative trait loci affecting growth and carcass traits in a cross population of beef and dairy cattle. J Anim Sci. 2009;87(1):24–36. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris CA, Cullen NG, Glass BC, Hyndman DL, Manley TR, Hickey SM, McEwan JC, Pitchford WS, Bottema CD, Lee MA. Fatty acid synthase effects on bovine adipose fat and milk fat. Mamm Genome. 2007;18(1):64–74. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0102-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyre D, Boutin P, Tounian A, Deweirder M, Aout M, Jouret B, Heude B, Weill J, Tauber M, Tounian P, Froquel P. Is glutamate decarboxylase 2 (GAD2) a genetic link between low birth weight and subsequent development of obesity in children? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):2384–2390. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Aldai N, Vinsky M, Dugan ME, McAllister TA. Association analyses of single nucleotide polymorphisms in bovine stearoyl-CoA desaturase and fatty acid synthase genes with fatty acid composition in commercial cross-bred beef steers. Anim Genet. 2012;43(1):93–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2011.02217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black AR, Black JD, Azizkhan-Clifford J. J Cell Physiol. Vol. 188. United States: 2001 Wiley-Liss, Inc; 2001. Sp1 and kruppel-like factor family of transcription factors in cell growth regulation and cancer; pp. 143–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer MC. Role of sp transcription factors in the regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(7):712–719. doi: 10.1177/1947601911423029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz G, Langmann T, Heimerl S. Role of ABCG1 and other ABCG family members in lipid metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(10):1513–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesta S, Bluher M, Yamamoto Y, Norris AW, Berndt J, Kralisch S, Boucher J, Lewis C, Kahn CR. Evidence for a role of developmental genes in the origin of obesity and body fat distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(17):6676–6681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601752103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Feng C, Ma L, Song C, Wang Y, Da Y, Li H, Chen K, Ye S, Ge C, Hu X, Li N. Genome-wide association study of body weight in chicken F2 resource population. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e21872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattle Genome UMD3.1. [ http://www.animalgenome.org/cgi-bin/gbrowse/bovine/]

- Inagaki K, Aki T, Fukuda Y, Kawamoto S, Shigeta S, Ono K, Suzuki O. Identification and expression of a rat fatty acid elongase involved in the biosynthesis of C18 fatty acids. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66(3):613–621. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton L, Kott T, Bures D, Rehak D, Zahradkova R, Kottova B. Meat Sci. Vol. 85. England: 2009 Elsevier Ltd; 2010. The polymorphisms of stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD1) and sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) genes and their association with the fatty acid profile of muscle and subcutaneous fat in Fleckvieh bulls; pp. 15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman EL, Nkrumah JD, Li C, Bartusiak R, Murdoch B, Moore SS. Fine mapping quantitative trait loci for feed intake and feed efficiency in beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2009;87(1):37–45. doi: 10.2527/jas.2008-0876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Huang W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker EJ, Jay JJ, Bubier JA, Langston MA, Chesler EJ. GeneWeaver: a web-based system for integrative functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D1067–D1076. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu ZL, Park CA, Wu XL, Reecy JM. Animal QTLdb: an improved database tool for livestock animal QTL/association data dissemination in the post-genome era. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D871–D879. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Laere AS, Nguyen M, Braunschweig M, Nezer C, Collette C, Moreau L, Archibald AL, Haley CS, Buys N, Tally M, Andersson G, Georges M, Andersson L. A regulatory mutation in IGF2 causes a major QTL effect on muscle growth in the pig. Nature. 2003;425(6960):832–836. doi: 10.1038/nature02064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper KE, Goddard ME. Understanding and predicting complex traits: knowledge from cattle. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(R1):R45-51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Go GW, Johnson BJ, Chung KY, Choi SH, Sawyer JE, Silvey DT, Gilmore LA, Ghahramany G, Kim KH. Adipogenic gene expression and fatty acid composition in subcutaneous adipose tissue depots of Angus steers between 9 and 16 months of age. J Anim Sci. 2012;90(8):2505–2514. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saatchi M, Garrick DJ, Tait RG Jr, Mayes MS, Drewnoski M, Schoonmaker J, Diaz C, Beitz DC, Reecy JM. Genome-wide association and prediction of direct genomic breeding values for composition of fatty acids in Angus beef cattlea. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):730. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D109–D114. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemoto Y, Abe T, Tameoka N, Hasebe H, Inoue K, Nakajima H, Shoji N, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi E. Whole-genome association study for fatty acid composition of oleic acid in Japanese Black cattle. Anim Genet. 2010;42(2):141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2010.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Yamaji K, Uemoto Y, Sasago N, Kobayashi E, Kobayashi N, Matsuhashi T, Maruyama S, Matsumoto H, Sasazaki S, Mannen H. Genome-wide association study for fatty acid composition in Japanese Black cattle. Anim Sci J. 2013;84(10):675–682. doi: 10.1111/asj.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizioto PC, Decker JE, Taylor JF, Schnabel RD, Mudadu MA, Silva FL, Mourão GB, Coutinho LL, Tholon P, Sonstegard TS, Rosa AN, Alencar MM, Tullio RR, Medeiros SR, Nassu RT, Feijó GLD, Silva LOC, Torres RA, Siqueira F, Higa RH, Regitano LCA. A genome scan for meat quality traits in Nelore beef cattle. Physiol Genomics. 2013;45(21):1012–1020. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00066.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espigolan R, Baldi F, Boligon AA, Souza FR, Gordo DG, Tonussi RL, Cardoso DF, Oliveira HN, Tonhati H, Sargolzaei M, Schenkel FS, Carvalheiro R, Ferro JA, Albuquerque LG. Study of whole genome linkage disequilibrium in Nellore cattle. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:305. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolormaa S, Pryce JE, Kemper KE, Hayes BJ, Zhang Y, Tier B, Barendse W, Reverter A, Goddard ME. Detection of quantitative trait loci in Bos indicus and Bos taurus cattle using genome-wide association studies. Genet Sel Evol. 2013;45:43. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-45-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolormaa S, Hayes BJ, Hawken RJ, Zhang Y, Reverter A, Goddard ME. J Anim Sci. Vol. 89. United States: 2011 American Society of Animal Science; 2011. Detection of chromosome segments of zebu and taurine origin and their effect on beef production and growth; pp. 2050–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizioto PC, Meirelles SL, Veneroni GB, Tullio RR, Rosa AN, Alencar MM, Medeiros SR, Siqueira F, Feijo GL, Silva LO, Torres RA, Jr, Regitano LCA. Meat Sci. Vol. 92. England: 2012 Elsevier Ltd; 2012. A SNP in ASAP1 gene is associated with meat quality and production traits in Nelore breed; pp. 855–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOCS. Official methods and recommended practices of the AOCS. 5. Champaign, IL: American Oil Chemists’ Society, AOCS; 2004. Rapid determination of oil/fat utilizing high temperature solvent extraction. AOCS Official Proc. Am 5-04. [Google Scholar]

- Hara A, Radin NS. Lipid extraction of tissues with a low-toxicity solvent. Anal Biochem. 1978;90(1):420–426. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie WW. In: Developments in Dairy Chemistry. Fox PF, editor. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Applied Science Publishers; 1983. The composition and structure of milk lipids; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- IUPAC. Compendium of Chemical Terminology. 2. Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1997. ((the "Gold Book"). Compiled by McNaught A.D. and Wilkinson A). [Google Scholar]

- llumina Inc. GenomeStudio Software v2011.1 Release Notes. 2011. [ http://supportres.illumina.com/documents/myillumina/1f2d00ae-b759-489b-82f9-0163ce085ae7/genomestudio_2011.1_release_notes.pdf]

- Gilmour AR, Gogel BJ, Cullis BR, Thompson R. Hemel Hempstead, HP1 1ES. UK: VSN International Ltd; 2009. ASReml User Guide Release 3.0. [Google Scholar]

- VanRaden PM. Efficient methods to compute genomic predictions. J Dairy. 2008;91(11):4414–4423. doi: 10.3168/jds.2007-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen TH, Hayes BJ, Goddard ME. Prediction of total genetic value using genome-wide dense marker maps. Genetics. 2001;157(4):1819–1829. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.4.1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habier D, Fernando RL, Kizilkaya K, Garrick DJ. Extension of the bayesian alphabet for genomic selection. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizilkaya K, Fernando RL, Garrick DJ. Genomic prediction of simulated multibreed and purebred performance using observed fifty thousand single nucleotide polymorphism genotypes. J Anim Sci. 2010;88(2):544–551. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onteru SK, Fan B, Nikkila MT, Garrick DJ, Stalder KJ, Rothschild MF. Whole-genome association analyses for lifetime reproductive traits in the pig. J Anim Sci. 2011;89(4):988–995. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]